Short abstract

Reports racial and ethnic differences on the California Well-Being Survey, a surveillance tool that tracks mental illness stigma and discrimination among a sample of California adults experiencing psychological distress.

Keywords: California, Discriminatory Practices, Health Care Program Evaluation, Mental Health and Illness, Social Determinants Of Health

Abstract

Reports racial and ethnic differences on the California Well-Being Survey, a surveillance tool that tracks mental illness stigma and discrimination among a sample of California adults experiencing psychological distress.

Key Findings

Regardless of race or ethnicity, the majority of California adults experiencing mental health challenges believe that individuals with a mental illness encounter high levels of prejudice and discrimination.

Asian-Americans reported higher levels of self-stigma (with respect to feeling inferior to others who have not had a mental health problem) and were less hopeful than whites that individuals with mental health problems could be contributing members of society.

Latinos interviewed in English also experienced higher levels of self-stigma (with respect to feeling embarrassed, ashamed, and not being understood because of a mental health problem) and were more likely to say that they would conceal a potential mental health problem from coworkers or classmates than whites.

Although Latinos interviewed in Spanish reported lower levels of stigma in a number of respects compared with whites, they were the least likely to have used mental health services of all the racial/ethnic groups included in the study.

Despite overall positive attitudes toward treatment across all racial and ethnic groups, many who needed mental health services were not receiving them. This was particularly true among Asian-Americans and Latinos surveyed in Spanish. Racial and ethnic minorities are significantly more likely than whites to delay or forego needed mental health care, and, if they do seek treatment, they are more likely than whites to drop out (McGuire and Miranda, 2008). Mental illness stigma and discrimination are thought to contribute to these racial/ethnic disparities in service utilization (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). The negative attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that the public holds toward people with mental illness (i.e., public stigma) may lead people to deny or conceal their mental health symptoms and avoid treatment (Clement et al., 2015; Corrigan, 2004). Moreover, when people with mental health challenges internalize negative societal beliefs about mental illness (i.e., self-stigma), this can lead to feelings of hopelessness or the “why try” effect, whereby individuals give up on treatment, employment, or other important endeavors that are integral to recovery (Corrigan, Larson, and Rüsch, 2009).

A limited number of studies have examined whether mental illness is more highly stigmatized in racial/ethnic minority communities. Studies conducted with samples representative of general populations in the United States have yielded mixed findings; racial and ethnic minorities have been found to have higher (Anglin, Link, and Phelan, 2006; Collins et al., 2014; Whaley, 1997), lower (Anglin, Link, and Phelan, 2006), or no different levels of stigma than whites (Kobau et al., 2010; Martin, Pescosolido, and Tuch, 2000). Fewer still are studies of representative samples of the general U.S. population that have examined racial/ethnic differences in stigma and discrimination among individuals who are experiencing mental health challenges. One study, involving a 2002 national survey of U.S. adults, examined the extent to which stigma and treatment attitudes figured as barriers to care among individuals who had acknowledged needing treatment but had not obtained it. This study found no significant racial/ethnic differences in reports of avoiding treatment out of fear of others finding out about their mental health problem or in beliefs about whether treatment is effective (Ojeda and Bergstresser, 2008). In another study conducted with a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults who met criteria for a mental health disorder, African-Americans were less embarrassed about seeking mental health care than whites (Diala et al., 2001).

The mixed findings of prior studies may be due to the fact that stigma manifests itself in a wide variety of ways (Link et al., 2004), and different studies have focused on different aspects of stigma, often confined to a single or only a few dimensions of stigma, such as perceptions of dangerousness (Anglin, Link, and Phelan, 2006; Whaley, 1997). In addition, some studies have been constrained by the combining of racial/ethnic minority groups likely due to small sample sizes (Martin, Pescosolido, and Tuch, 2000), by the inclusion of only a single racial/ethnic minority group (Anglin, Link, and Phelan, 2006; Diala et al., 2001), or by the inability to assess for differences within a racial/ethnic group based on English-language proficiency (Kobau et al., 2010; Ojeda and Bergstresser, 2008). Significant disparities have been found, with non--English-speaking individuals from racial/ethnic minority groups being significantly less likely to obtain needed mental health treatment than their English-speaking counterparts (Sentell, Shumway, and Snowden, 2007).

To address the gaps in our understanding of how mental illness stigma affects racial and ethnic minorities, the present study capitalized on data collected for the California Well-Being Survey (CWBS), a RAND survey conducted with a representative sample of California adults who are experiencing psychological distress. The CWBS was developed and administered in 2014 to track exposure to, and the impact of, prevention and early intervention (PEI) activities administered by the California Mental Health Services Authority (CalMHSA). With funding from California's Mental Health Services Act (Proposition 63), CalMHSA implemented three statewide PEI initiatives focusing on mental illness stigma and discrimination reduction (SDR), suicide prevention, and student mental health that began in 2011. The CWBS assesses a wide variety of factors that may influence how individuals would respond if they were to experience mental health challenges, including perceptions of public stigma, recovery beliefs, treatment attitudes, self-recognition of mental health problems, mental health service utilization, and exposure to PEI activities. The CWBS is also the first study to assess the pervasiveness of self-stigma (i.e., negative feelings about one's own mental illness) and experiences of mental illness--related discrimination using a sample that is representative of individuals who are at risk for or are experiencing mental health problems. In contrast, previous studies examining mental illness stigma and discrimination among individuals experiencing mental health challenges have been largely limited to individuals recruited from mental health service or advocacy organizations (Brohan et al., 2011; Henderson et al., 2012), which may yield biased estimates given that a large percentage of the broader population of individuals affected by mental health challenges do not engage in treatment.

In this article, we examine whether there are racial/ethnic differences among California adults experiencing mental health challenges with respect to stigma, including their views of the public's treatment of people with mental health challenges, attitudes toward recovery from mental illness, self-recognition of mental health problems, self-stigma, discrimination, mental health treatment attitudes and utilization, and exposure to CalMHSA's SDR activities. Given that California is one of the most racially and ethnically diverse states in the nation, the CWBS affords us a unique opportunity to systematically examine whether mental illness stigma disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities.

Our findings indicate that perceptions of public stigma and experiences of discrimination are high across all racial and ethnic groups. However, Asian-Americans and Latinos surveyed in English are disproportionately affected by higher levels of self-stigma in particular. The picture is complex for Latinos surveyed in Spanish, who simultaneously had greater levels of stigma in certain domains (e.g., beliefs that people with mental illness are never going to contribute to society) and lower levels in others (e.g., concealment of a mental health problem from coworkers/classmates). Even though all racial and ethnic groups had positive attitudes toward treatment, we nonetheless found that a large proportion of individuals experiencing psychological distress had not obtained mental health services. Asian-Americans and Latinos who completed the survey in Spanish were the least likely to acknowledge having a mental health problem and had disconcertingly low levels of mental health service use, even among those with serious levels of distress.

Method

The CWBS is a follow-up survey of adults (aged 18 years or older) who participated in the 2013 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS). The CHIS is a random-dial telephone survey conducted with a representative sample of Californians focusing on a variety of health issues, including mental health. All adults who had completed the 2013 CHIS (N = 20,724), were willing to be recontacted, had completed the interview in English or Spanish, and had mild to moderate or serious levels of psychological distress as assessed by the Kessler-6 (K-6) scale were eligible to participate in the CWBS (N = 2,395). The K-6 is a brief six-item scale used to screen for clinically significant mental health problems (Kessler et al., 2003). A K-6 score greater than 12 is indicative of probable serious mental illness. Various cut-points have been used for defining other levels of psychological distress. We chose scores ranging from 9 to 12 to indicate mild to moderate psychological distress, following the original proponents of a polychotomous (multiple subgroups) approach to the K-6 (Furukawa et al., 2003).

The CWBS was administered in English or Spanish between May and August 2014. A total of 1,066 adults completed the CWBS, representing a final response rate of 45.2 percent. Fifty-four percent (N = 578) had K-6 scores in the mild to moderate range and 46 percent (N = 488) had scores in the serious distress range at the time that they were screened by CHIS. Characteristics of the sample are provided in Table 1. Latinos who chose to complete the survey in English and those who chose to complete the survey in Spanish were studied separately. People who endorsed multiple racial backgrounds were categorized as “other.”

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants in the 2014 California Well-Being Survey

| Characteristics | Unweighted Frequency | Weighted Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 694 | 59 |

| Age | ||

| 18--29 | 141 | 30 |

| 30--39 | 79 | 19 |

| 40--49 | 158 | 18 |

| 50--64 | 447 | 27 |

| 65 or older | 241 | 7 |

| Race/Ethnicitya | ||

| Asian-American | 29 | 7 |

| African-American | 48 | 6 |

| Latino (English survey) | 156 | 26 |

| Latino (Spanish survey) | 103 | 16 |

| White | 646 | 39 |

| Other | 84 | 6 |

| Employmentb | ||

| Employed for wages | 325 | 41 |

| Self-employed | 93 | 9 |

| Looking for work | 91 | 13 |

| Retired | 277 | 10 |

| Homemaker/keeping house | 80 | 12 |

| Disabled | 261 | 16 |

| Student | 76 | 14 |

NOTES: To provide estimates that are representative of the California distressed population, weighted percentages were calculated to adjust for undercoverage, subsample selection, nonresponse, and ineligibility resulting from when the CHIS 2013 sample was recontacted to participate in the CWBS. Sample-based raking, a multidimensional poststratification procedure, was used to compute the weights. Key variables used to create raking dimensions were age, sex, race/ethnicity, home ownership, region of the state, educational attainment, and cell phone versus landline phone. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Racial/ethnic minority groups (with the exception of Latinos) and respondents aged 65 years or older comprised only a small proportion of the CWBS sample. This is reflective of the sociodemographic profile of eligible CHIS 2013 respondents. Respondents of “other” ethnicity were excluded from the analyses given the heterogeneity of this group.

Participants could select more than one category.

Results

Perceptions of Public Stigma and Support

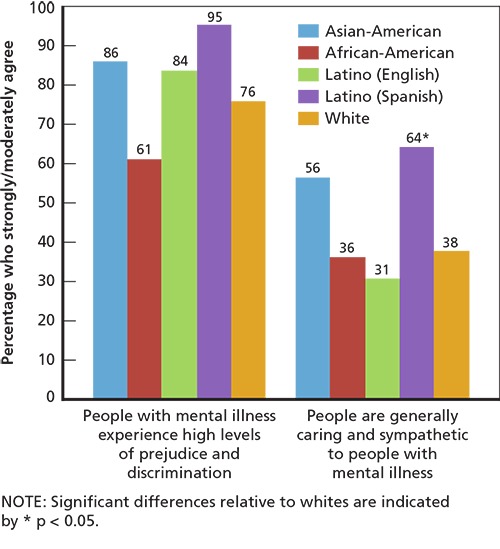

Perceptions of how the public views and treats those with mental illness may influence an individual's decision to disclose a mental health problem as well as his or her willingness to seek treatment (Clement et al., 2015; Corrigan, 2004). Irrespective of race or ethnicity, most people surveyed believe that individuals with mental illness experience high levels of stigma and discrimination (see Figure 1). Across most groups, only a small proportion viewed the public as being caring and sympathetic toward people with mental illness. There was one exception: A significantly greater proportion of Latinos surveyed in Spanish (64 percent) viewed the public as being supportive of people with mental illness relative to whites (38 percent).

Figure 1.

Perceptions of Public Stigma and Support

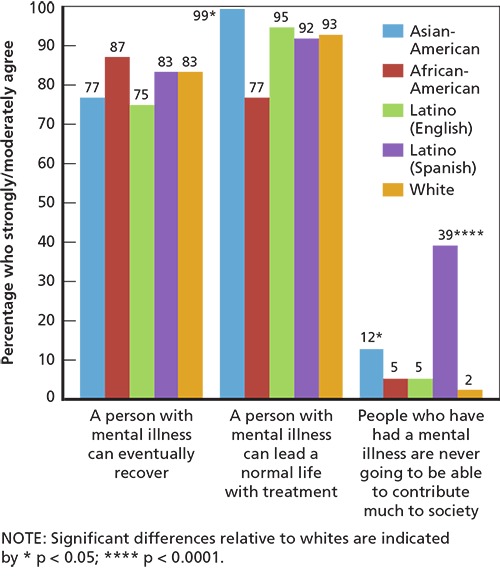

Recovery Beliefs

Beliefs about recovery from mental illness may affect whether individuals experiencing mental health challenges reach out for help from family or professionals (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention et al., 2012; Clement et al., 2015). We found that the majority of those surveyed, regardless of racial or ethnic background, believed that a person who seeks treatment for a mental illness can eventually recover and lead a normal life (see Figure 2). Asian-Americans were significantly more likely than whites to agree that individuals with a mental illness can lead a normal life with treatment. However, on the question of whether people who have experienced a mental illness will ever be able to contribute much to society, we observed notable racial/ethnic differences. Relative to whites (2 percent), a significantly greater proportion of Asian-Americans (12 percent) and Latinos surveyed in Spanish (39 percent) believed that those who have experienced a mental illness are never going to be able to contribute to society.

Figure 2.

Recovery Beliefs

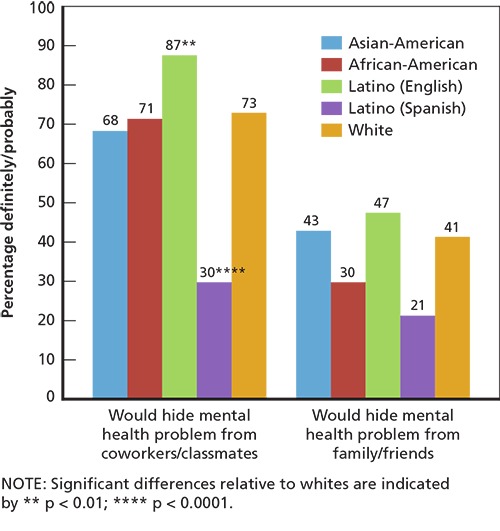

Concealment of Mental Health Problems

Fear of social judgment, rejection, and discrimination may motivate individuals to conceal mental health challenges (Clement et al., 2015). Nearly 90 percent of Latinos surveyed in English indicated that they would conceal a mental health problem from coworkers or classmates (see Figure 3). Conversely, Latinos surveyed in Spanish were the group least likely to conceal a mental health problem from coworkers or classmates, with only one-third endorsing such an intention. This may be related to the fact that Latinos surveyed in Spanish were more likely to perceive the public as caring and sympathetic toward people with mental health challenges (see Figure 1). No significant racial or ethnic group differences were found in concealing a mental health problem from family or friends.

Figure 3.

Concealment of Mental Health Problems

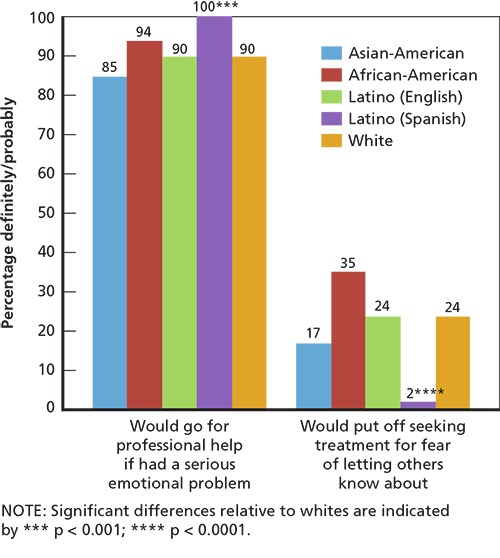

Treatment Attitudes

Nearly everyone surveyed, across all racial/ethnic groups, indicated that they would seek professional help for a serious emotional problem, including 100 percent of Latinos surveyed in Spanish, which was significantly higher than whites (see Figure 4). Latinos surveyed in Spanish were also the group least likely to report that they would delay treatment out of fear of letting others know about a mental health problem (2 percent), a rate significantly lower than that reported by whites (24 percent). These findings are consistent with a study involving a representative sample of U.S. Latinos, in which Latinos with limited English proficiency were less likely to report being embarrassed if friends found out they were getting mental health treatment than were Latinos with a higher English proficiency (Bauer, Chen, and Alegría, 2010).

Figure 4.

Treatment Attitudes

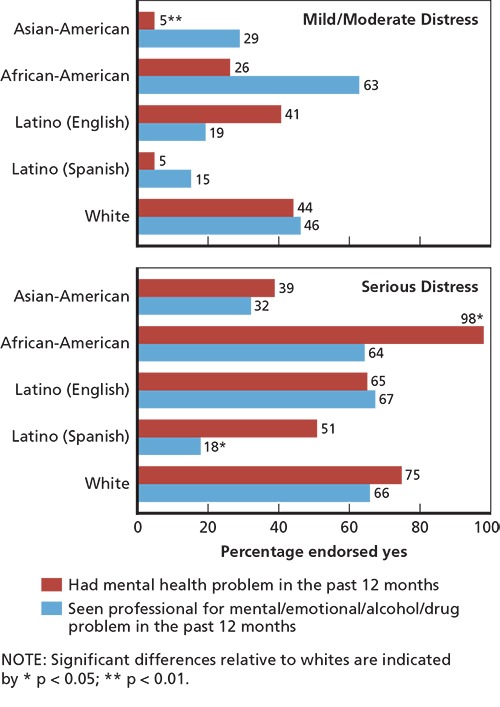

Self-Recognition and Treatment of Mental Health Problems

People experiencing psychological distress may not recognize their symptoms as a sign of a mental health problem or may be reluctant to do so out of a desire to avoid being labeled as having a mental illness (Corrigan and Wassel, 2008; Jorm, 2012). Among individuals with mild to moderate distress (i.e., those with K-6 scores between 9 and 12), we found that Asian-Americans (5 percent) and Latinos surveyed in Spanish (5 percent) were the least likely to report having a mental health problem in the past 12 months (see Figure 5). No significant racial/ethnic group differences in treatment use, however, were found for these individuals. Among those with serious distress (i.e., K-6 scores greater than 12 and most likely to meet criteria for a mental disorder), we found that African-Americans (98 percent) were significantly more likely to report experiencing a mental health problem in the past 12 months than whites (75 percent). This could be related to African-Americans experiencing greater disability and impairment when affected by a mental health condition (Williams et al., 2007). As similarly observed in the lower-distress group, Asian-Americans with serious distress were the least likely to report a recent mental health problem (39 percent). With respect to treatment use in the group with serious distress, Latinos surveyed in Spanish (18 percent) were the least likely to obtain mental health services (differing significantly from whites, 66 percent); Asian-Americans had the second lowest rate of treatment use (32 percent). Contrary to prior findings (Ault-Brutus, 2012; Wang et al., 2005), African-Americans did not use mental health services at lower rates than whites.

Figure 5.

Self-Recognized Mental Health Problem and Treatment Use Among Participants with Mild to Moderate Versus Serious Distress

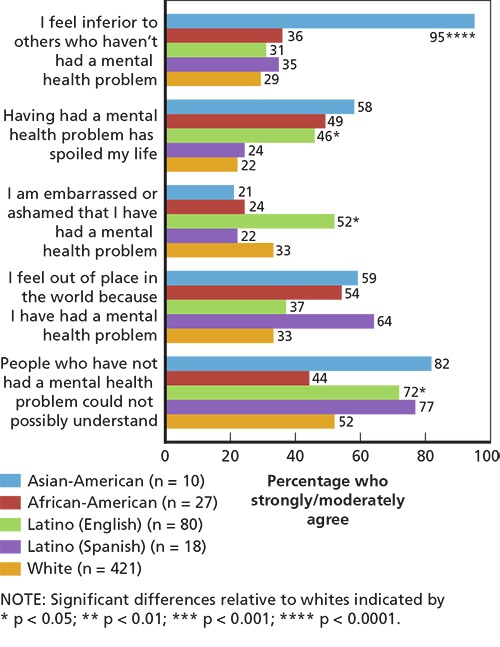

Self-Stigma and Experienced Discrimination

Self-stigma and discrimination are corrosive experiences that can impede one's recovery from a mental health challenge and worsen a person's quality of life (Corrigan, Larson, and Rüsch, 2009; Mittal et al., 2012). One of the most frequently reported types of self-stigma is alienation, which is related to subjective experiences of having a “spoiled identity” (Goffman, 1963) or not feeling fully part of society (Brohan et al., 2011; Ritsher, Otilingam, and Grajales, 2003). In our sample, Asian-Americans and Latinos surveyed in English were significantly more likely to feel alienated because of their mental health challenges than whites (see Figure 6). Ninety-five percent of Asian-Americans who reported experiencing a mental health problem said that they felt inferior to those who had not experienced a mental health problem, compared with 29 percent of whites. Latinos surveyed in English were significantly more likely than whites to report that having a mental health problem had spoiled their life (46 percent), made them feel embarrassed or ashamed (52 percent), and that people who have not experienced mental health issues cannot understand them (72 percent).

Figure 6.

Self-Stigma

The self-stigma items were administered only to individuals who indicated having experienced a mental health problem, given that the items asked about the negative impact of having a mental health problem. Only a very small number of Asian-Americans and Latinos surveyed in Spanish reported a mental health problem, so percentages in this section should be interpreted with caution. For the same reason, some apparent differences for these groups are not reliable enough to achieve statistical significance. For instance, Latinos surveyed in Spanish were also more likely to endorse several of the self-stigma items than whites, but the differences were not statistically significant.

We assessed recent experiences of discrimination (i.e., being treated unfairly in the prior 12 months because of a mental health problem) among individuals who indicated experiencing a mental health problem in the prior 12 months. As seen in Table 2, a greater proportion of Latinos surveyed in English (49 percent) reported experiencing discrimination by the police, and a significantly smaller proportion of African-Americans (3 percent) reported experiencing discrimination with regard to housing (both relative to whites). Most groups experienced discrimination most frequently within the realm of intimate social relationships (e.g., family, dating, marriage, friends), although there were some exceptions. For instance, Latinos surveyed in Spanish experienced the highest levels of discrimination in their interactions with physical health providers and the legal system. Consistent across all racial/ethnic groups, the large majority of individuals experiencing recent mental health challenges reported being discriminated against in at least one of the domains assessed.

Table 2.

Percentage Who Reported Experiencing Discrimination in Prior 12 Months

| Asian-American (n = 7) | African-American (n = 19) | Latino (English) (n = 54) | Latino (Spanish) (n = 9) | White (n = 247) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the past 12 months, because of your mental health problem, how often have you been treated unfairly … | |||||

| … by your family (not including your spouse/live-in partner) | 99 | 76 | 69 | 24 | 65 |

| … in dating/intimate relationships | 75 | 75 | 72 | 11 | 59 |

| … in your marriage, live-in partnership, divorce, or separation | 27 | 67 | 65 | 16 | 60 |

| … when trying to make/keep friends | 75 | 59 | 66 | 20 | 52 |

| … by one or more of your employers | 15 | 36 | 51 | 8 | 48 |

| … in school or on the job training | 50 | 37 | 59 | 19 | 39 |

| … in your social activities | 65 | 15 | 51 | 4 | 38 |

| … by the police | 70 | 59 | 49** | 10 | 22 |

| … by potential employers when looking for a job | 15 | 29 | 45 | 6 | 35 |

| … by the people in your neighborhood | 49 | 36 | 37 | 16 | 34 |

| … by physical health care providers and staff | 7 | 51 | 30 | 75 | 32 |

| … by mental health care providers and staff | 14 | 57 | 38 | 5 | 32 |

| … by other people in the legal system (lawyers, judges, or corrections officers) | 64 | 30 | 35 | 70 | 24 |

| … when trying to find/keep housing | 1 | 3** | 33 | 6 | 21 |

| Any Discrimination | 100**** | 89 | 92 | 100**** | 84 |

NOTES: Often, sometimes, and rarely responses were considered reports of discrimination, in order to correspond with estimates from the Corker et al. (2013) study, which reported on the percentage that endorsed a lot, moderately, or a little response options. Significant differences relative to whites indicated by

p < 0.01;

p < 0.0001.

The sample sizes in this subset were very small for some groups, especially for Asian-Americans and Latinos surveyed in Spanish. Consequently, these results should be viewed with caution as well. What appear to be large differences between groups are not statistically significant, and the apparent differences may be unreliable given the small samples. With these caveats in mind, very few racial/ethnic differences in these domains were found.

Exposure to CalMHSA and Other Stigma and Discrimination Reduction Activities

CalMHSA's SDR initiative included a social marketing campaign, the creation and distribution of informational materials (including via websites), efforts to alter portrayals of mental illness in entertainment media and journalism, and educational presentations and trainings in community and work settings. The CWBS asked people about their exposure to these activities during the 12 months prior to their survey interview. Some activities were clearly “branded,” such as those from the social marketing campaigns, and so could be specifically attributed to CalMHSA. Other activities were funded by CalMHSA, including a wide variety of educational presentations and materials, but were administered by a range of organizations and under a range of different labels. Additionally, other entities in the state were simultaneously conducting similar activities. Thus, it is difficult to determine whether people who were exposed to SDR activities were reached by CalMHSA or by one of these other efforts. We categorized activities that could be directly linked to CalMHSA as “CalMHSA reach,” and the others as “other reach.”

CalMHSA Reach. CalMHSA SDR social marketing campaigns included “Each Mind Matters” and “ReachOut,” which had Spanish-language versions, “SanaMente” and “BuscaApoyo,” respectively. ReachOut targeted young people aged 14 to 24. The SDR social marketing campaign also included the distribution of a documentary entitled “A New State of Mind: Ending the Stigma of Mental Illness,” which showcases the lives of people who have experienced mental health challenges and recovery. The documentary debuted on California Public Television (CPT) during primetime and was re-aired on various CPT stations at different times and days. The documentary was also distributed at planned community screening events and on CalMHSA's Each Mind Matters website, which also houses other SDR materials. EachMindMatters.org has become a hub for CalMHSA's PEI resources more broadly, and the slogan “Each Mind Matters” now accompanies all CalMHSA resources and activities.

We found that the television documentary “A New State of Mind” reached a significantly greater proportion of Latinos surveyed in Spanish (30 percent) than whites (7 percent) (see Table 3). In contrast, only 1 percent of Asian-Americans viewed the documentary. There were no significant group differences in the level of awareness of the “Each Mind Matters” slogan or in the number of visits to EachMindMatters.org. More than 40 percent of Latinos surveyed in Spanish had heard about or seen an advertisement for ReachOut.com, which is more than six times the rate reported by whites (7 percent). Only 1 percent of Asian-Americans had heard or seen advertisements for the ReachOut website. Although actual visits to the ReachOut website were low across all groups, relative to whites, rates were significantly lower for African-Americans and Latinos surveyed in English, none of whom reported any visits. The ReachOut website also had not reached any Asian-Americans. In terms of activities that could be directly linked to CalMHSA, efforts appeared to be more effective in reaching African-Americans (49 percent) and Latinos surveyed in Spanish (59 percent) than whites (27 percent).

Table 3.

Potential Exposure to SDR Activities

| Asian-American | African-American | Latino (English) | Latino (Spanish) | White | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CalMHSA reach | |||||

| Watched television documentary “A New State of Mind” | 1** | 14 | 15 | 30** | 7 |

| Seen or heard slogan or catch phrase “Each Mind Matters” or ”SanaMente” | 10 | 37 | 20 | 23 | 22 |

| Visited website EachMindMatters.org | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Seen or heard ad for “ReachOut” or ”BuscaApoyo” | 1 | 19 | 7 | 43**** | 7 |

| Visited the website ReachOut.Com | 0 | 0*** | 0* | 1 | 3 |

| Other reach | |||||

| Watch any documentary about mental illness | 11 | 25 | 38** | 46* | 21 |

| Seen an advertisement or promotion for a television documentary about mental illness | 12 | 43 | 41* | 40 | 29 |

| Watched some other movie or television show in which a character had a mental illness | 53 | 56 | 61 | 69 | 74 |

| Seen or heard a news story about mental illness | 47 | 76 | 55* | 79 | 69 |

| Visited another website to get information about mental illness | 25 | 36 | 33 | 4**** | 37 |

| Attended an educational presentation or training either in person or online about mental illness | 13 | 35 | 13 | 3** | 17 |

| As part of your profession, received advice about how to discuss mental illness or interact with a person with mental illness | 25 | 50* | 24 | 21 | 22 |

| Received documents or other informational resources related to mental illness through the mail, email, online, or in person | 12** | 65* | 44 | 5**** | 37 |

| Any CalMHSA reach | 11 | 49* | 32 | 59** | 27 |

| Other reach | 97 | 86 | 85 | 83 | 92 |

NOTES: Significant differences relative to whites indicated by

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001;

p < 0.0001.

Other Reach. The reach of activities that cannot be directly linked to, but could still be part of, CalMHSA's activities varied in notable ways across racial and ethnic groups (see Table 3). For example, Asian-Americans (12 percent) were less likely to report having received informational resources about mental illness than whites (37 percent). In contrast, African-Americans (65 percent) were more likely to have received such informational resources than whites. African-Americans (50 percent) were also more likely to have received on-the-job guidance about mental health issues than whites (22 percent). Latinos surveyed in English were more likely to report having seen a documentary about mental illness (38 percent), but less likely to have seen or heard a news story about mental illness (55 percent) than whites (21 percent and 69 percent, respectively). Latinos surveyed in Spanish were also more likely to have seen a documentary about mental illness, but were less likely to have been reached by other websites containing information about mental illness (4 percent), educational presentations or trainings (3 percent), or informational resources (5 percent). In spite of these variations in exposure to specific activities, we found no differences in reach overall. Members of different racial and ethnic groups were equally likely to report being reached by at least one of the “other reach” SDR activities, with the large majority of respondents (83--97 percent) reporting some such exposure.

Conclusions

This study examined whether racial and ethnic groups differ in their experiences of mental illness stigma and discrimination across a broad array of domains, and is unique in its use of a representative sample of individuals who are experiencing mental health challenges. Across all racial/ethnic groups, most people surveyed believed that individuals with mental illness experience high levels of prejudice and discrimination. This fits with the fact that a substantial proportion of those surveyed reported being discriminated against because of their mental illness. Yet, significant racial/ethnic differences were found. In a number of domains, Asian-Americans and Latinos held more negative views of mental illness, though the patterns were more complex for Latinos, for whom substantial variations were found depending on the language they chose for their interviews. For Asian-Americans, stigma appears to figure most prominently in their beliefs about the level of functioning and status of individuals with mental health problems. Compared with whites, Asian-Americans were less likely to view individuals with mental health problems as being able to contribute much to society, and they were more likely to feel inferior to those who have not had a mental illness. This may be due in part to the emphasis in some Asian cultures on high levels of achievement and social comparison to others, particularly when failures are encountered (Kramer et al., 2002; White and Lehman, 2005). Studies conducted with general samples of individuals who have not necessarily experienced a mental health problem have similarly found that, relative to whites, Asian-Americans hold more negative attitudes toward people with mental illness, perceive them to be more dangerous, and desire greater social distance from them (Collins et al., 2014; Eisenberg et al., 2009; Rao, Feinglass, and Corrigan, 2007; Whaley, 1997). A growing body of evidence indicates that Asian-Americans may harbor more stigmatizing attitudes toward those with mental illness, which in turn may translate into higher levels of self-stigma (i.e., feeling inferior to others who have not had a mental health problem) for Asian-Americans who themselves experience mental health challenges.

For Latinos, substantial differences were found depending on the language in which they were surveyed. Latinos surveyed in English experienced greater stigma in several respects. They reported higher levels of self-stigma (e.g., feeling ashamed because of their mental health problem) and were more likely to conceal a potential mental health problem from coworkers or classmates than whites. In contrast, relative to whites, Latinos interviewed in Spanish seemed to experience lower levels of stigma in several domains: They were less likely to report intentions to delay treatment or hide a mental health problem from coworkers or classmates, and were more likely to report intentions to obtain treatment if needed. Latinos surveyed in Spanish also were more likely to perceive others as being caring and sympathetic toward individuals with mental illness than whites. Yet, at the same time, Latinos surveyed in Spanish were nearly 20 times more likely than whites to doubt that individuals with mental health problems could be contributing members of society. Moreover, the recognition of a mental health problem and the use of mental health services were lowest among Latinos surveyed in Spanish.

We used the language in which Latinos completed the survey as a crude measure of acculturation, the degree to which Latinos adopt U.S. cultural norms. Our results suggest that acculturation may affect Latinos' experience of stigma in important ways. Perhaps Latinos surveyed in Spanish may not have viewed their symptoms as a sign of a mental health problem. Some Latino groups have been found to employ culturally specific conceptualizations of mental illness, such as the use of the idiom “nervios” (i.e., nerves) to describe mental illness symptoms, which some see as a way of decreasing stigma and garnering family support (López, 2002). There is also evidence that Latinos with limited English proficiency may be less likely to stigmatize treatment for a mental health problem. In a study conducted with a representative sample of Latinos in the United States who had a diagnosable mental health condition, Latinos with limited English proficiency were significantly less likely to report feeling embarrassed about obtaining mental health treatment than were Latinos with greater English proficiency (Bauer et al., 2010). Additional research could help us better understand these findings and examine why less-acculturated Latinos on the one hand appear to view treatment favorably and see the public as generally supportive of people with mental illness, but on the other appear to be the least likely to seek treatment or recognize in themselves a mental health problem.

African-Americans did not appear to differ from whites on the various indicators of stigma assessed in the CWBS. This is consistent with prior studies involving population-based samples with established mental health needs. In a survey of a representative sample of community residents in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, African-Americans and whites who had depressive symptoms exhibited no significant differences in their perceptions of public stigma or their experiences of self-stigma (Brown et al., 2010). Moreover, in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults who met criteria for a mental disorder, African-Americans were significantly less likely to be embarrassed about seeking mental health care and more likely to report intentions to seek professional help than whites (Diala et al., 2001). African-Americans have also expressed more positive attitudes toward treatment than whites (Anglin et al., 2008).

The vast majority of CWBS respondents across all racial and ethnic groups felt that it was possible to recover from mental illness. Most respondents, regardless of their racial or ethnic background, indicated that they would obtain mental health treatment if needed. Yet unmet need for mental health treatment (i.e., people not getting the treatment they need) continues to be a significant public health issue. Among CWBS respondents with serious psychological distress, more than one-third of African-Americans and Latinos surveyed in English had not obtained treatment. Rates were even higher for Asian-Americans and Latinos surveyed in Spanish, 68 percent and 82 percent of whom, respectively, had not sought treatment despite serious levels of distress. One of the primary goals of CalMHSA's PEI initiative is to reduce the unmet need for mental health services. Our findings indicate that CalMHSA's PEI activities were particularly effective at reaching African-Americans and Latinos surveyed in Spanish, and these were also the two groups that expressed the most willingness to seek treatment. Further research is warranted on how exposure to CalMHSA's PEI activities affects stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs across racial and ethnic groups.

Our study had certain limitations. To assess for potential mental health need, we relied on the K-6 scale, a nonspecific psychological distress screener, which has been a valid screener for serious mental illness but may be more strongly correlated with anxiety and depression than with other mental disorders (Andrews and Slade, 2001; Kessler et al., 2010). Analyses were limited by small sample sizes for some racial and ethnic groups, and analyses involving self-stigma and discrimination were subject to particularly restricted sample sizes since these items were administered only to the subset of people who acknowledged experiencing a mental health problem. Findings need to be verified with larger numbers of racial and ethnic minorities, even though doing so will be a challenge. This study also did not contain sufficient sample sizes to examine potential subgroup differences among Asian-Americans and Latinos from different countries, who have varied cultural experiences. Because our only measure of acculturation among Latinos was the language they chose for their interview, we were limited in our ability to investigate how varying levels of acculturation may relate to experience of stigma and discrimination. Moreover, our study was limited to Asian-Americans who were able to complete the interview in English.

Despite these limitations, this is the first study to take a comprehensive look at racial and ethnic differences across a wide variety of stigma domains with a representative sample of individuals who are experiencing mental health challenges. Emerging evidence suggests that Asian-Americans are disproportionately affected across a range of stigma experiences. Further, more-acculturated Latinos appear to experience higher levels of self-stigma than their less-acculturated counterparts, who also, surprisingly, have more positive attitudes toward treatment than whites. Finally, African-Americans and whites appear to experience similar levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination.

Our findings underscore the importance of understanding how mental illness stigma affect racial and ethnic minorities, both in terms of how widespread it is and its impact on recovery. Further study examining how the effects of stigma and discrimination on mental health service use may differ across racial and ethnic groups could aid in the development of tailored interventions to address widely known and persistent treatment disparities.

Footnotes

This research was conducted in RAND Health, a division of the RAND Corporation.

References

- Andrews G. Slade T. Interpreting Scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2001;25(6):494–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglin D. Alberti P. Link B. Phelan J. Racial Differences in Beliefs About the Effectiveness and Necessity of Mental Health Treatment. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;42(1--2):17–24. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9189-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglin D. Link B. Phelan J. Racial Differences in Stigmatizing Attitudes Toward People with Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(6):857–862. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ault-Brutus A. Changes in Racial-Ethnic Disparities in Use and Adequacy of Mental Health Care in the United States, 1990--2003. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(6):531–540. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A. M. Chen C.-N. Alegría M. English Language Proficiency and Mental Health Service Use Among Latino and Asian Americans with Mental Disorders. Medical Care. 2010;48(12):1097–1104. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f80749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brohan E. Gauci D. Sartorius N. Thornicroft G. GAMIAN-Europe Study Group. Self-Stigma, Empowerment and Perceived Discrimination Among People with Bipolar Disorder or Depression in 13 European Countries: The GAMIAN-Europe Study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;129(1--3):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. Conner K. O. Copeland V. C. Grote N. Beach S. Battista D. Reynolds C. F. Depression Stigma, Race, and Treatment Seeking Behavior and Attitudes. Journal of Community Psychology. 2010;38(3):350–368. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Association of County Behavioral Health and Developmental Disability Directors, National Institute of Mental Health, The Carter Center Mental Health Program. Attitudes Toward Mental Illness: Results from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Atlanta, Ga.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Clement S. Schauman O. Graham T. Maggioni F. Evans-Lacko S. Bezborodovs N. Morgan C. Rüsch N. Brown J. S. Thornicroft G. What Is the Impact of Mental Health--Related Stigma on Help-Seeking? A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(1):11–27. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins R. Wong E. Cerully J. Roth E. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Mental Illness Stigma in California. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2014. [As of February 18, 2016]. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR684.html [Google Scholar]

- Corker E. Hamilton S. Henderson C. Weeks C. Pinfold V. Rose D. Williams P. Flach C. Gill V. Lewis-Holmes E. Thornicroft G. Experiences of Discrimination Among People Using Mental Health Services in England 2008--2011. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;202(s55):s58–s63. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.112912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. How Stigma Interferes with Mental Health Care. American Psychologist. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. Larson J. Rüsch N. Self-Stigma and the ‘Why Try’ Effect: Impact on Life Goals and Evidence-Based Practices. World Psychiatry. 2009;9(2):75–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. W. Wassel A. Understanding and Influencing the Stigma of Mental Illness. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 2008;46(1):42–48. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20080101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diala C. C. Muntaner C. Walrath C. Nickerson K. LaVeist T. Leaf P. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Mental Health Services. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(5):805. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D. Downs M. F. Golberstein E. Zivin K. Stigma and Help Seeking for Mental Health Among College Students. Medical Care Research and Review. 2009;66(5):522–541. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T. A. Kessler R. C. Slade T. Andrews G. The Performance of the K6 and K10 Screening Scales for Psychological Distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33(2):357–362. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc.; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson R. Corker E. Lewis-Holmes E. Hamilton S. Flach C. Rose D. Williams P. Pinfold V. Thornicroft G. England's Time to Change Antistigma Campaign: One-Year Outcomes of Service User-Rated Experiences of Discrimination. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(5):451–457. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A. F. Mental Health Literacy: Empowering the Community to Take Action for Better Mental Health. American Psychologist. 2012;67(3):231–243. doi: 10.1037/a0025957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. Barker P. Colpe L. Epstein J. F. Gfroerer J. Hiripi E. Normand S. L. Manderscheid R. W. Walters E. E. Zaslavsky A. M. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C. Green J. G. Gruber M. J. Sampson N. A. Bromet E. Cuitan M. Furukawa T. A. Gureje O. Hinkov H. Hu C. Y. Lara C. Lee S. Mneimneh Z. Myer L. Oakley-Brown M. Posada-Villa J. Sagar R. Viana M. C. Zaslavsky A. M. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population with the K6 Screening Scale: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;19(S1):4–22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobau R. DiIorio C. Chapman D. Delvecchio P. SAMHSA/CDC Mental Illness Stigma Panel Members. Attitudes About Mental Illness and Its Treatment: Validation of a Generic Scale for Public Health Surveillance of Mental Illness Associated Stigma. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;46(2):164–176. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9191-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer E. J. Kwong K. Lee E. Chung H. Cultural Factors Influencing the Mental Health of Asian Americans. Western Journal of Medicine. 2002;176(4):227–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B. G. Yang L. H. Phelan J. C. Collins P. Y. Measuring Mental Illness Stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30(3):511–541. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López S. R. Mental Health Care for Latinos: A Research Agenda to Improve the Accessibility and Quality of Mental Health Care for Latinos. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53(12):1569–1573. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. K. Pescosolido B. A. Tuch S. A. Of Fear and Loathing: The Role of ‘Disturbing Behavior,’ Labels, and Causal Attributions in Shaping Public Attitudes Toward People with Mental Illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(2):208–223. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire T. G. Miranda J. New Evidence Regarding Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health: Policy Implications. Health Affairs. 2008;27(2):393–403. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal D. Sullivan G. Chekuri L. Allee E. Corrigan P. W. Empirical Studies of Self-Stigma Reduction Strategies: A Critical Review of the Literature. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(10):974–981. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda V. D. Bergstresser S. M. Gender, Race-Ethnicity, and Psychosocial Barriers to Mental Health Care: An Examination of Perceptions and Attitudes Among Adults Reporting Unmet Need. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49(3):317–334. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D. Feinglass J. Corrigan P. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Mental Illness Stigma. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195(12):1020–1023. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31815c046e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher J. B. Otilingam P. G. Grajales M. Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness: Psychometric Properties of a New Measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121(1):31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentell T. Shumway M. Snowden L. Access to Mental Health Treatment by English Language Proficiency and Race/Ethnicity. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(Suppl. 2):289–293. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0345-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity---A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2001. Rockville, Md.

- Wang P. S. Berglund P. Olfson M. Pincus H. A. Wells K. B. Kessler R. C. Failure and Delay in Initial Treatment Contact After First Onset of Mental Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley A. Ethnic and Racial Differences in Perceptions of Dangerousness of Persons with Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48(10):1328–1330. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.10.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K. Lehman D. R. Culture and Social Comparison Seeking: The Role of Self-Motives. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31(2):232–242. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. González H. M. Neighbors H. Nesse H. R. Abelson J. M. Sweetman J. Jackson J. S. Prevalence and Distribution of Major Depressive Disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]