Short abstract

This first population-based study of care received by service members with mild traumatic brain injury in the Military Health System profiles patients, their care settings and treatments, co-occurring conditions, and risk factors for long-term care.

Keywords: Defense Health Agency, Health Care Quality, Military Veterans, Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is considered a signature injury of modern warfare, though TBIs can also result from training accidents, falls, sports, and motor vehicle accidents. Among service members diagnosed with a TBI, the majority of cases are mild TBIs (mTBIs), also known as concussions. Many of these service members receive care through the Military Health System, but the amount, type, and quality of care they receive has been largely unknown. A RAND study, the first to examine the mTBI care of a census of patients in the Military Health System, assessed the number and characteristics (including deployment history and history of TBI) of nondeployed, active-duty service members who received an mTBI diagnosis in 2012, the locations of their diagnoses and next health care visits, the types of care they received in the six months following their mTBI diagnosis, co-occurring conditions, and the duration of their treatment. While the majority of service members with mTBI recover quickly, the study further examined a subset of service members with mTBI who received care for longer than three months following their diagnosis. Diagnosing and treating mTBI can be especially challenging because of variations in symptoms and other factors. The research revealed inconsistencies in the diagnostic coding, as well as areas for improvement in coordinating care across providers and care settings. The results and recommendations provide a foundation to guide future clinical studies to improve the quality of care and subsequent outcomes for service members diagnosed with mTBI.

Of the approximately 2.5 million service members who have deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan in support of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom, more than 50,000 were wounded in action, and between 30 and 50 percent of these injuries were the result of improvised explosive devices (IEDs; U.S. Department of Defense [DoD], 2014; Wilson, 2006). Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a frequent consequence of IED incidents, so much so that it is considered the signature injury of modern warfare (Altmire, 2007; Clark, 2006).

Deployment-related injuries are not the only driver of TBIs, however. Such injuries may also result from training accidents, accidental falls, sports, and motor vehicle accidents. In fact, non--deployment-related TBIs accounted for 85 percent of all TBIs reported to DoD between 2001 and 2011 (Office of the Surgeon General, 2013).

Estimates vary, but studies suggest that 8--20 percent of service members may have experienced a TBI (Hoge, McGurk, et al., 2008; Schell and Marshall, 2008). Among those diagnosed with TBI, the majority of cases (84 percent) were considered mild in severity (Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center [DVBIC], 2014a). Many service members who have experienced a mild TBI (mTBI), also known as a concussion, receive care through the Military Health System (MHS), but the frequency and nature of their post-injury health care has not been described in a large cohort. To address this gap, DoD asked the RAND Corporation to survey the current landscape of mTBI treatment across the MHS. The goal of this research is to provide timely information to DoD that can be used to help assess and improve care for service members with mTBI.

Mild cases of TBI can be challenging to identify and treat due to variations in symptom presentation and other factors. To deliver the most efficient and effective treatment for service members with mTBI, it is important to first understand how many and which service members receive an mTBI diagnosis, where they receive care, the types of treatment they receive, and the duration of their care. The ultimate goal of improving the care delivered to this population (and subsequent clinical outcomes) depends on a solid evidence base. This study provides a first step in establishing that base by describing the service member population diagnosed with an mTBI, their clinical characteristics, and the care they receive.

Because of the difficulty in accurately diagnosing mTBI and variability in screening procedures, there have been calls for clear and consistent definitions of study populations and standard guidelines for diagnosis (see, e.g., Helmick et al., 2012; Hoge, McGurk, et al., 2008). The research community has also highlighted the need to account for conditions often present with mTBI, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression (Carlson et al., 2011; Kristman et al., 2014). This study---the first comprehensive analysis of the types and patterns of care delivered by the MHS to service members following an mTBI diagnosis---aims to fill some of these gaps.

The findings presented here lay the groundwork for future research to assess and improve the quality of care by characterizing the population of service members who have received care for mTBI through the MHS, as well as the care that they have received, using health care utilization data. We began by evaluating multiple methods of identifying service members with mTBI using diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), Clinical Modification. Then, we drew on individual health care utilization records to characterize service members who received a diagnosis of mTBI and assessed the care they received, including the types of care, the settings in which the care was provided, and the types of providers who delivered the care. Finally, we explored patterns of care, describing health care received up to six months after an mTBI diagnosis, including the duration and patterns of utilization. In addition, we explored care provided to service members who received “persistent care,” defined as care received beyond three months following an injury.

The results of this study are intended to support the MHS in its effort to deliver care more effectively and efficiently to service members diagnosed with an mTBI. However, they should also prove valuable to other health systems and health care professionals and officials involved with treating or setting policies regarding the treatment of service members and civilians with mTBI.

Identifying Service Members Treated for mTBI

For patients with a moderate or severe TBI, long-term outcomes can vary from full recovery to complete dependence on care providers. Measurable deficits in cognitive and physical functioning may still be present a year after the injury (Andelic et al., 2010; Novack et al., 2000). In contrast, symptoms associated with mTBI tend to resolve quickly for the majority of patients. Previous studies suggest that the majority of symptoms tend to resolve within the first month after an mTBI incident (Lundin et al., 2006; McCrea, Guskiewicz, et al., 2003), and, according to data on civilian patients, 85--90 percent with mild TBI recover within three months (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs [VA], 2010). However, for some people, symptoms and cognitive deficits can persist for years (Ruff, 2005).

To understand the care received by nondeployed active-duty service members after an mTBI diagnosis, we analyzed individual-level health care utilization data. These administrative data detail when a service member visits a health care provider; characteristics of those visits, such as the location of care and the provider who treated the service member; the diagnoses and procedures that are recorded during those visits; and prescriptions filled by the service member. These data do not include clinical notes entered into the medical record by providers.

Military health care utilization data are managed and maintained by the Defense Health Agency, and the files used in our analysis were extracted from the MHS Data Repository. The repository contains records on all health care encounters paid for by the MHS; our analysis focused on health care use among nondeployed active-duty service members who received an mTBI diagnosis in calendar year 2012 and only health care received in garrison. We were not able to observe health care received in theater. The files were linked by scrambled Social Security numbers, so we were able to follow individual service members over time.

To augment the health care utilization data, we used individual-level data from the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC), which included the dates and locations of service members' deployments; service characteristics, such as rank and years of service; and dates of service, including separation date. These records were also linked by scrambled Social Security numbers, allowing us to match the identifiers in the Defense Health Agency data.

Drawing on these sources, we identified all active-component service members who had at least one health care encounter for an mTBI diagnosis in calendar year 2012. To do this, we first needed to select a case definition for mTBI. We conducted a search of the peer-reviewed and gray literature to identify existing case definitions for mTBI; compared the various existing definitions according to comprehensiveness, agreement, and other factors; and, in consultation with an expert advisory group, selected a working definition for the project. We also conducted analyses to determine the implications of selecting one definition over another.

The case definition for mTBI we selected is based on the ICD-9 and is used by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Using this definition, we examined the number of nondeployed active-duty service members who received treatment for an mTBI over five years (2008--2013), then compared our estimates to published DoD estimates of the number of service members with mTBI. We excluded National Guard and reserve service members from the analysis. It is likely that these service members have access to other health insurance, and we were not able to observe care that was not paid for by the MHS.

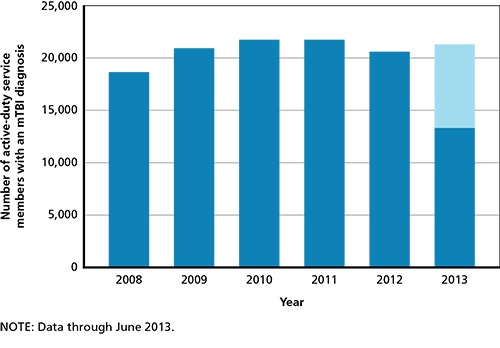

Figure 1 shows the number of active-component service members who received treatment for an mTBI diagnosis between 2008 and 2013, according to our data. As shown in the figure, the number of service members who received treatment increased from 2008 to 2009 (from approximately 18,700 to nearly 22,000 cases), after which the number remained roughly steady through 2012.1

Figure 1.

Number of Nondeployed Active-Duty Service Members Who Received an mTBI Diagnosis, 2008--2013

Characterizing Service Members Diagnosed with mTBI

We assessed the demographics, service history characteristics, and co-occurring conditions of the population of nondeployed active-duty service members who received treatment for a new mTBI in 2012, the most recent complete year of data at the time of this study. We defined a “new” mTBI as receipt of care associated with an mTBI diagnosis following a period of six months with no treatment for a TBI diagnosis.

We report sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, TRICARE region, branch of service, and rank, along with years of service and whether the service member had a history of deployments. We used DMDC data to determine whether a given service member had deployed since 2001;2 those who had deployed since 2001 were characterized as having a “history of deployment.” For characteristics that change over time (such as age), we report the value of the characteristic at the time of the first visit for the new mTBI.

Nondeployed Active-Duty Service Members with a New mTBI Tended to Be Young and Junior Enlisted

We found that nondeployed active-duty service members diagnosed with a new mTBI in 2012 tended to be relatively young and lower-ranked. Specifically, half of these service members were junior enlisted personnel at the time of diagnosis.3 Service members with a new mTBI in 2012 had completed an average of six years of service, and two-thirds had a history of deployment. On average, those with a history of deployment had been deployed for 16 cumulative months prior to their 2012 mTBI diagnosis. These numbers varied by service, however, with Army personnel considerably more likely to have been deployed (79 percent), and for seven to nine months longer, than personnel from other service branches.

We also wanted to determine whether those service members with a new mTBI diagnosis in 2012 had previously received treatment for a TBI. Those who had received a TBI diagnosis of any severity in the years preceding the mTBI diagnosis in 2012 (i.e., between 2008 and 2011) were characterized as having a “history of TBI.” We found that 10 percent of the 2012 mTBI cohort had received treatment for a previous TBI between 2008 and 2011.

Many Nondeployed Active-Duty Service Members with a New mTBI Received Treatment for Co-Occurring Behavioral Health Conditions, Pain, and Sleep Disorders

We used two methods to identify relevant co-occurring diagnoses in our study population. First, we reviewed the mTBI literature to develop a list of symptoms and conditions that occasionally or commonly occur as sequelae to mTBI (see, e.g., Borgaro et al., 2003; Lundin et al., 2006; Vaishnavi, Rao, and Fann, 2009).

Second, we examined the frequency of all ICD-9 codes associated with health care encounters in the six months following the first (diagnosis) visit for mTBI in our study population. Since service members may suffer other injuries as a consequence of the event that caused the mTBI, some of the symptoms and conditions we observed in the data may have been related to those injuries. We derived a subset of co-occurring conditions that were either commonly reported in the literature or frequently present in the mTBI cohort:

behavioral health conditions: adjustment disorders, PTSD, other anxiety disorders (anxiety disorder not otherwise specified, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder), depression (major depressive disorder, dysthymia), acute stress disorders, bipolar disorder, delirium or dementia, attention deficit or attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, alcohol abuse or dependence, and drug abuse or dependence

symptoms commonly or occasionally co-occurring with mTBI: headache, other chronic pain, sleep disorders, irritability, memory loss, dizziness/vertigo, hearing problems, post-concussion syndrome, syncope and collapse, cognitive problems, skin sensation disturbances, alteration in mental status, gait and coordination problems, vision problems, communication disorders, and smell and taste disturbances.

We found that 11--16 percent of service members in the 2012 mTBI cohort received treatment for behavioral health conditions in the six months following their mTBI diagnosis, with adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, depression, alcohol abuse/dependence, and PTSD the most common conditions for which service members received treatment. We observed that the mTBI diagnosis co-occurred with an increase in the proportion of service members who received treatment for behavioral health conditions; a smaller proportion (4--10 percent) received treatment for these conditions in the six months before mTBI diagnosis than in the six months after mTBI diagnosis.

In addition, in the six months following their mTBI diagnosis, many service members with a new mTBI received treatment for co-occurring headache (40 percent), back and neck pain (21 percent), and sleep disorders (25 percent). While some had received treatment for these conditions prior to the mTBI diagnosis (e.g., 12 percent had received treatment for back and neck pain in the six months before the mTBI diagnosis), for all conditions we examined, a higher proportion received treatment for these conditions after the mTBI diagnosis than before. We were also able to assess the clusters of diagnoses for these co-occurring conditions, finding that, for example, 68 percent of those who received treatment for headache also received treatment for a non-headache pain conditions and that 43 percent of those who received treatment for sleep disorders also received treatment for memory loss.

Analyzing Patterns of Care for Service Members Diagnosed with mTBI

Clinical research suggests that symptoms for most individuals with mTBI resolve within one month of the injury (Lundin et al., 2006; McCrea, Guskiewicz, et al., 2003). The symptoms and care of a small but not insignificant number of patients may persist to three months, and the symptoms of an even smaller group may persist for six months or longer. To ensure that we examined all potentially relevant care for every potential individual in our analysis, we selected an observation period of six months, though not all care observed during this time period was necessarily associated with the mTBI. We examined the clinical setting in which service members in the 2012 mTBI cohort received their mTBI diagnosis, the setting in which they had their next health care encounter, their patterns of health care use, and the types of assessments and treatments they received in the six months after the mTBI diagnosis.

Most Nondeployed Active-Duty Service Members with a New mTBI in 2012 Were Diagnosed in an Emergency Department and Had Their Next Health Care Visit in a Primary Care Setting

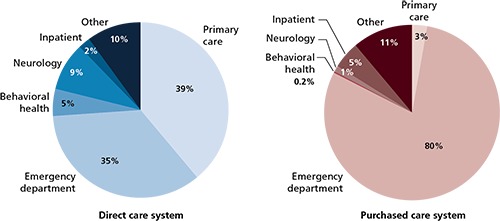

We characterized the treatment settings where service members in the mTBI cohort received care. We distinguished between direct care, which is care received at military treatment facilities (MTFs), and purchased care, which is care received in the community and paid for by TRICARE. We also identified whether the setting was a primary care clinic, emergency department, behavioral health specialty clinic, neurology clinic, inpatient facility, or other location.4 In addition, we categorized the physical locations where service members in the mTBI cohort received care.

We found that 60 percent of the mTBI cohort was diagnosed in the direct care system; of these service members, 40 percent were diagnosed at a primary care clinic, and 35 percent received their diagnosis in an emergency department. Among the 40 percent who were diagnosed through the civilian purchased care network, the vast majority (80 percent) received their diagnosis in an emergency department. Thus, overall, half of all nondeployed active-duty service members with a new mTBI were diagnosed in an emergency department (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Location of mTBI Diagnosis in the Direct and Purchased Care Systems

On average, service members in the 2012 mTBI cohort had their next health care encounter 17 days after the mTBI diagnosis, and these visits took place in the direct care system for 87 percent of the cohort. Nearly half of those visits took place in a primary care setting. Service members with a history of TBI or deployment were more likely to have their next health care encounter at a behavioral health clinic, compared with those without histories of deployment or TBI, who were more likely to be seen at a primary care clinic.

Most Nondeployed Active-Duty Service Members with mTBI Recovered Quickly

To identify patterns of care over the six-month time frame, we defined several time segments of treatment following the mTBI diagnosis, including treatment received within the first 24 hours and every week thereafter. We examined whether service members received any care (for any diagnosis or procedure), care potentially related to the mTBI (based on diagnosis codes for personal history of TBI), care for symptoms related to mTBI, and care for behavioral health diagnoses. Our findings agreed with the clinical research: The majority of service members in our cohort (80--90 percent) received care for three months or less following their initial mTBI diagnosis, with most (75--80 percent) receiving care for four weeks or less. However, a subset (10--20 percent) appeared to have persistent care needs---that is, they received ongoing mTBI-related care for longer than three months after the 2012 mTBI diagnosis.

Many Nondeployed Active-Duty Service Members with a New mTBI Received Diagnostic Assessments, Therapy, and Medications in the Six Months Following the mTBI Diagnosis, with Differences by TBI History

We identified diagnostic assessments, therapies, and medications potentially relevant to the treatment of common or occasional symptoms and conditions that can co-occur with mTBI using an approach similar to that described for comorbid diagnoses. First, we reviewed DoD/VA clinical practice guidelines (VA and DoD, 2009) for the treatment of mTBI and clinical guidance for the treatment of related symptoms (e.g., headache). We then developed a list of relevant assessments, therapies, and medications. We also reviewed the literature on the treatment of mTBI and consulted with an expert advisory group to identify additional relevant treatment. Finally, we examined the frequency of procedure codes (Current Procedural Terminology codes) associated with health care visits in the six months following the mTBI diagnostic visit, selecting those that were commonly received by the 202 mTBI cohort.

While we were not able to determine whether these were related to the mTBI or for another reason, the most common diagnostic assessments performed on nondeployed active-duty service members with a new mTBI were CT scans (33 percent), psychiatric diagnostic evaluations (28.7 percent), and physical therapy evaluations (24.8 percent). For almost every assessment or evaluation, service members with a history of TBI (any level of severity) were more likely than those without a history of TBI to receive these and other assessments and evaluations in the six months following their mTBI diagnosis.

The most frequently recommended initial treatment for mTBI is rest and patient education, activities that were not observable in our health care utilization data. However, many patients with mTBI receive care beyond the initial visit; as such, we report treatments received by the 2012 mTBI cohort in the six months following the mTBI diagnosis. We were not able to determine whether the care received was for the mTBI or for another condition, as current TBI coding guidance recommends that health care visits after the initial visit include symptom diagnostic codes rather than a TBI-related diagnostic code. As such, it is not possible to determine from these data whether physical therapy, for example, is related to the mTBI or a different condition.

Psychotherapy and physical therapy were the most common treatments received by the 2012 mTBI cohort in the six months following the mTBI diagnosis. As with diagnostic assessments, members of the cohort who experienced a prior TBI at the time of diagnosis were more likely to receive these treatments.

We also examined medication use, though, again, we were not able to attribute any filled prescriptions to the mTBI directly. We found that 60 percent of the cohort filled a prescription for analgesics in the six months following diagnosis, and half filled prescriptions for opioids; antidepressants were filled by one-quarter of the cohort. We observed that some had filled prescriptions for these medications prior to the mTBI diagnosis as well as after the diagnosis, indicating ongoing treatment for an unrelated condition (e.g., 15 percent filled a prescription for an opioid before and after the mTBI diagnosis), but the proportion who filled prescriptions for all medications we examined was higher after the mTBI diagnosis than before. Service members with a history of TBI at the time of their mTBI diagnosis were more likely to fill most types of prescriptions than were those without a history of TBI.

A Minority of Nondeployed Active-Duty Service Members with a New mTBI in 2012 Had Complex and Persistent Care Needs

We analyzed the characteristics and risk factors for those with persistent mTBI care needs. To identify potential risk factors among those needing persistent care, we calculated the adjusted relative risk for demographic characteristics and service history characteristics. Relative risk indicates the strength of the association between a characteristic and an outcome.

We identified 1,678 nondeployed active-duty service members with a new mTBI in 2012 who received mTBI-related treatment (indicated by a diagnosis of personal history of TBI) for longer than three months after the mTBI diagnosis (“persistent care”). We found that having a history of TBI was a significant risk factor for receiving persistent care following an mTBI diagnosis (see Table 1). A service member was almost 50 percent more likely to receive persistent care if he or she had a previous TBI. We did not find a statistical relationship between sex and persistent care, contrary to findings from previous studies. We also found that those who had been deployed were two and a half times more likely to receive persistent care.

Table 1.

Adjusted Relative Risk for Nondeployed Active-Duty Service Members Receiving Treatment 90 Days or More After mTBI Diagnosis, by Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | 2012 mTBI Cohort (n = 16,378) | Persistent Care (n = 1,678) | Adjusted Relative Risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | % | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 14,202 | 1,548 | 92.3 | 1.18 |

| Female | 2,176 | 130 | 7.7 | 0.85 |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| 18--34 | 14,018 | 1,352 | 80.6 | 0.75* |

| 35 and older | 2,360 | 326 | 19.4 | 1.33* |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 10,699 | 1,165 | 69.4 | 1.03 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2,319 | 190 | 11.3 | 0.79*** |

| Hispanic | 1,843 | 200 | 11.9 | 0.97 |

| Other/unknown | 1,517 | 123 | 7.3 | 1.14 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 9,149 | 1,160 | 69.1 | 1.12 |

| Never married | 6,444 | 422 | 25.1 | 0.72*** |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 778 | 96 | 5.7 | 1.24* |

| Region | ||||

| TRICARE North | 4,421 | 431 | 25.8 | 1.14 |

| TRICARE South | 3,335 | 258 | 15.4 | 0.90 |

| TRICARE West | 6,930 | 821 | 49.1 | 1.26** |

| TRICARE Overseas | 1,539 | 150 | 9.0 | 1.17 |

| TBI history | 1,611 | 294 | 17.5 | 1.48*** |

| Service branch | ||||

| Army | 8,791 | 1,306 | 77.8 | 3.75*** |

| Navy | 2,191 | 60 | 3.6 | 0.71 |

| Air Force | 2,686 | 46 | 2.7 | 0.41*** |

| Marine Corps | 2,248 | 261 | 15.6 | 3.74*** |

| Other/unknown | 462 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.25** |

| Deployment history | 10,857 | 1,496 | 89.2 | 2.50*** |

NOTES: The relative risk is adjusted for gender, age, race, marital status, TRICARE region, TBI history, service branch, cumulative months of deployment, years of service, and deployment history. The analysis is based on health care encounters for personal history of TBI (ICD-9 code V15.52). Ninety days or more of treatment equates to persistent care. Numbers may not sum due to missing data.

Statistically significant difference at p < 0.001.

Statistically significant difference at p < 0.01.

Statistically significant difference at p < 0.05.

Strengths and Limitations of Our Approach

We used administrative health care utilization data for this analysis that captured medical care details for the population of nondeployed active-duty service members who received a new mTBI diagnosis in 2012. These data also included characteristics of the care they received following the mTBI diagnosis, including co-occurring diagnoses, procedures, medications, and the location and setting of care, as well as the demographic and service characteristics of individual patients. The data allowed us to describe health care utilization within a six-month period after an mTBI diagnosis and explore patterns of care that other data sources, such as surveys and reviews of medical records, would not allow.

Despite the comprehensiveness of these data, the analyses presented here have some limitations. First, we were not able to attribute care received after an mTBI diagnosis to the injury itself. This is because current coding guidance requires that the mTBI diagnostic code be recorded at the initial visit but not during subsequent visits. The coding guidance requires that providers record the diagnostic codes at subsequent visits for the chief complaint (e.g., headache), rather than the injury itself. This means that it was not possible to reliably determine whether subsequent assessments, treatments, or medications were part of mTBI treatment or unrelated to the mTBI.

Second, the data covered only care provided at MTFs and through the civilian purchased care network while service members were stationed in garrison. If a service member experienced an mTBI during a deployment, the data did not capture the initial diagnosis or any care received in theater. Relatedly, mTBI is often underdiagnosed (Powell et al., 2008); if service members received care for an mTBI but never received an mTBI diagnosis, that case would not be included in our data.

To identify diagnoses, we relied on ICD-9 diagnostic codes. In selecting and employing our ICD-9--based case definition of mTBI, we identified important issues related to the reliability and utility of this approach:

Prevalence estimates of mTBI are highly sensitive to case definitions. Estimates of TBI are extremely sensitive to case definitions (AFHSC, 2009), and various definitions have been suggested for identifying TBI using ICD-9 diagnoses. This has resulted in a lack of easy comparability across research sources and settings.

Providers, within and across health care systems, are challenged by distinct and evolving coding guidance. Patients move between military and civilian health care settings, where providers use unique coding rules for mTBI. Further, as understanding about mTBI has progressed since the start of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, guidance for mTBI coding has also evolved, resulting in multiple iterations of coding guidance within the past 15 years. For administrative codes to be applied consistently, there must be a shared understanding of how the codes are supposed to be applied. The rapid evolution of coding guidance and confusion among providers who work across health care systems are real challenges for the consistency of coding practices as it relates to mTBI.

Recommendations

1. Improve ICD-9 Coding Practices and Reconsider Current TBI Coding Guidance

Good administrative data should be considered integral to health care quality because these data help track the status of patients and the treatments and procedures they receive. DoD TBI coding guidance requires that providers record a TBI diagnosis only at the first visit, with subsequent visits coded with relevant symptom diagnostic codes rather than the TBI diagnostic code. As a result, it is not possible to use administrative data to observe treatment for mTBI over time. DoD should consider whether the advantages of the current TBI coding guidance outweigh the disadvantages for understanding the nature of care provided to service members with TBI.

2. Improve Data Quality to Increase Capacity for Research

The nature and purpose of administrative data pose real challenges for their use in research. Administrative data are collected for multiple purposes, including legal and financial reviews, that are largely unrelated to surveillance and research. This limits the data's utility for analysis. Improving connections between administrative claims and other clinical data (e.g., chart data, pharmacy data) is one way to enhance their value. The current lack of connectivity limits the use of the data for clinically relevant research. For example, it is often difficult to determine, using administrative data, whether referrals were followed up on or whether a prescription that was ordered was filled. Creating more interoperable data streams will facilitate a wide range of research.

3. Identify Opportunities to Coordinate Care

Our results demonstrate that nondeployed active-duty service members diagnosed with mTBI receive subsequent treatment in a variety of clinical settings. While not unique to mTBI, the specific challenges faced by these service members (and their providers) highlight the need for coordination of care and communication across providers, especially across direct- and purchased-care settings. It is important to understand current challenges and strategies for care coordination in this population and then identify best practices. Broader health system changes, such as the introduction of patient-centered care homes, may provide opportunities to coordinate care across provider types for service members with mTBI. Another approach could be to increase the role of the DVBIC Recovery Support Program or similar initiatives. The DVBIC recovery support specialists may be an effective means of enhancing coordination across providers, settings, and systems (Martin et al., 2013)

4. Assess Quality of Care for Service Members with mTBI

This study describes the types and patterns of care received by a cohort of service members with mTBI. However, our analyses were limited to variables available in an administrative data set, and we were unable to assess the quality of the care provided. Future efforts should extend our analysis to examine not only the type of care provided but also its quality. These studies will need to incorporate other data sources, as the administrative data do not include the details necessary to assess adherence to clinical practice guidelines. In addition, given the variability in symptom presentation and recovery, additional work is warranted to further develop standards of care for mTBI.

5. Extend These Results with Hypothesis-Driven, Multivariate Analyses

This study was designed to establish a foundation for hypothesis-directed clinical studies. To that end, we identified a number of areas that should be explored with further multivariate analyses to help the MHS confirm and interpret the relationships among patient, clinician, and setting factors in care patterns and outcomes for service members with mTBI. Multivariate regression can take multiple variables into account, helping to clarify when observed differences may be due to other factors. In particular, we recommend that future analyses focus on the following:

Examine co-occurring conditions and symptoms. A number of co-occurring clinical conditions identified in our cohort should be considered for further examination. An extension of this research could involve factor analysis, cluster analysis, or other approaches that expand the scope from considering pairs of variables to considering multiple variables. If such clusters could be identified and account for a substantial portion of the variation in the original data, then these clusters might be useful for subsequent analyses, such as those regarding episodes of care. Such an endeavor would be complex, requiring substantial thought and care in conceptualizing these dependencies. It would likely require a novel conceptual model to rule out many contingencies and alternative explanations.

Explore predictors of care patterns. Characterizing the course of care is a critical step in building statistical approaches to predicting it. The concept of a care episode, as used in this study, is one such approach, but specific inquiries could also examine particular aspects of the course of care. For example, does the course of care differ by diagnostic setting? Does the course of care differ for those who receive care from a TBI clinic? To what extent do variations in care patterns reflect differences in the initial severity of an mTBI?

Explore variation in care. Our results offer some evidence of variation in care by service and history of TBI. Variation in care could reflect actual differences in the populations receiving treatment. MTFs and their providers could appropriately adjust their approach to diagnosis and treatment according to the unique needs of individual service members. Alternatively, variations in care could be associated with poorer quality of care. Understanding the reasons for observed differences can inform quality improvement initiatives and reduce inappropriate variations in care.

Examine a clinical cohort with persistent mTBI-related problems. Some service members have persistent mTBI care needs. To address these needs, improved understanding of this group is required. As a first step, it will be important to accurately identify service members who have ongoing care needs and to further understand the risk factors associated with persistent care. While administrative data allowed us to examine persistent care among the population of service members with mTBI, there are the limitations to this approach, most notably issues associated with proper diagnostic coding. Other data sources, such as clinical data or medical record data, would help in better identifying service members with long-term needs.

Concluding Thoughts

As a signature injury of modern warfare, TBI affects more service members than ever before. Mild TBI, the most common TBI severity, can be challenging to identify and treat due to variations in symptom presentation and other factors. This study presents information to answer questions about how many and which service members receive an mTBI diagnosis, where they receive care, the types of treatment they receive, and for how long they receive care. The important baseline information presented here is a key step toward the ultimate goal of providing high-quality care for service members receiving treatment for mTBI in the MHS.

Notes

TRICARE encounter data were extracted on or around October 24, 2013. Direct care data are considered complete within 90 days of an encounter; purchased care data are complete within 120 days. Therefore, we had access to complete direct and purchased care data through the end of June 2013. We extrapolated through the end of the calendar year to generate an estimate of 21,212 mTBI cases in 2013.

Our deployment data from DMDC's Contingency Tracking System included service members who were physically located in a designated combat zone or area of operation or who were specifically identified as directly supporting a deployment.

See Cameron et al. (2012) for details on the link between junior rank and incidence of mTBI diagnosis.

We were able to identify whether service members in the mTBI cohort received care from the Veterans Health Administration, but these cases accounted for fewer than 1 percent of the claims in our data.

This research was sponsored by the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center in the Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury and conducted within the Forces and Resources Policy Center of the RAND National Defense Research Institute, a federally funded research and development center sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the Joint Staff, the Unified Combatant Commands, the Navy, the Marine Corps, the defense agencies, and the defense Intelligence Community.

References

- AFHSC ---See Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center.

- Altmire Jason. U.S. Representative from Pennsylvania, testimony on legislation affecting veterans before the Subcommittee on Health. Committee on Veterans' Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives; Washington, D.C.: [April 26, 2007]. [Google Scholar]

- Andelic Nada. Sigurdardottir Solrun. Schanke Anne-Kristine. Sandvik Leiv. Sveen Unni. Roe Cecilie. Disability, Physical Health and Mental Health 1 Year After Traumatic Brain Injury. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2010;32(13):1122–1131. doi: 10.3109/09638280903410722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Deriving Case Counts from Medical Encounter Data: Considerations When Interpreting Health Surveillance Reports. Medical Surveillance Monthly Report. 2009 Dec;16(12):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Borgaro Susan R. Prigatano George P. Kwasnica Christina. Rexer Jennie L. Cognitive and Affective Sequelae in Complicated and Uncomplicated Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Brain Injury. 2003 Mar;17(3):189–198. doi: 10.1080/0269905021000013183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron Kenneth L. Marshall Stephen W. Sturdivant Rodney X. Lincoln Andrew E. Trends in the Incidence of Physician-Diagnosed Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Among Active Duty U.S. Military Personnel Between 1997 and 2007. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2012 May 1;29(7):1313–1321. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Kathleen F. Shannon Kehle M. Meis Laura A. Greer Nancy. Macdonald Roderick. Rutks Indulis. Sayer Nina A. Dobscha Steven K. Wilt Timothy J. Prevalence, Assessment, and Treatment of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2011 Mar-Apr;26(2):103–115. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181e50ef1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark John. Casualty of War. Newsweek. Mar 16, 2006.

- DoD ---See U.S. Department of Defense.

- Helmick Kathy. Baugh Laura. Lattimore Tracy. Goldman Sarah. Traumatic Brain Injury: Next Steps, Research Needed, and Priority Focus Areas. Military Medicine. 2012 Aug;177(8):86–92. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00174. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge Charles W. McGurk Dennis. Thomas Jeffrey L. Cox Anthony L. Engel Charles C. Castro Carl A. Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in US Soldiers Returning from Iraq. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Jan 31;358:453–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristman Vicki L. Borg Jörgen. Godbolt Alison K. Rachid Salmi L. Cancelliere Carol. Carroll Linda J. Holm Lena W. Nygren-de Boussard Catharina. Hartvigsen Jan. Abara Uko. Donovan James. David Cassidy J. Methodological Issues and Research Recommendations for Prognosis After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Results of the International Collaboration on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Prognosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2014 Mar;95(3):S265–S277. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.04.026. Suppl. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundin A. de Boussard C. Edman G. Borg J. Symptoms and Disability Until 3 Months After Mild TBI. Brain Injury. 2006;20(8):799–806. doi: 10.1080/02699050600744327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Laurie T. Farris Coreen. Parker Andrew M. Epley Caroline. The Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center Care Coordination Program: Assessment of Program Structure, Activities, and Implementation. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2013. [As of January 13, 2015]. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR126.html [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea Michael. Guskiewicz Kevin M. Marshall Stephen W. Barr William. Randolph Christopher. Cantu Robert C. Onate James A. Yang Jingzhen. Kelly James P. Acute Effects and Recovery Time Following Concussion in Collegiate Football Players: The NCAA Concussion Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003 Nov 19;290(19):2556–2563. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novack Thomas A. Alderson Amy L. Bush Beverly A. Meythaler Jay M. Canupp Kay. Cognitive and Functional Recovery at 6 and 12 Months Post-TBI. Brain Injury. 2000 Nov;14(11):987–996. doi: 10.1080/02699050050191922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Surgeon General. TBI Talking Points 2013. 2013. Washington, D.C.

- Powell Janet M. Ferraro Joseph V. Dikmen Sureyya S. Temkin Nancy R. Bell Kathleen R. Accuracy of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Diagnosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2008 Aug;89(8):1550–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Laurie M. Warden Deborah L. Post Concussion Syndrome. International Review of Psychiatry. 2003 Nov;15(4):310–316. doi: 10.1080/09540260310001606692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell Terry L. Marshall Grant N. Jaycox Lisa H. Survey of Individuals Previously Deployed for OEF/OIF. In: Tanielian Terri., editor; Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2008. [As of January 13, 2015]. pp. 87–113.http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG720.html [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense. U.S. casualty status tables. web page, data as of December 31, 2014. No longer available online.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Independent Course on Traumatic Brain Injury. Apr, 2010. [As of January 13, 2015]. http://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/vhi/traumatic-brain-injury-vhi.pdf

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense. Clinical Practice Guideline: Management of Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, version 1.0. Apr, 2009. [As of January 13, 2015]. http://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/mtbi/concussion_mtbi_full_1_0.pdf Washington, D.C.

- VA ---See U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

- Vaishnavi Sandeep. Rao Vani. Fann Jesse R. Neuropsychiatric Problems After Traumatic Brain Injury: Unraveling the Silent Epidemic. Psychosomatics. 2009 May-Jun;50(3):198–205. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Clay. Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) in Iraq and Afghanistan: Effects and Countermeasures. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service; Sep 25, 2006. [Google Scholar]