Abstract

Previous studies with mice lacking secreted IgM (sIgM) due to a deletion of the μs splice region (μs−/−) had shown sIgM involvement in normal B cell development and in support of maximal antigen-specific IgG responses. Because of the changes to B cell development, it remains unclear to which extent and how sIgM directly affects B cell responses. Here we aimed to explore the underlying mechanisms of sIgM-mediated IgG response regulation during influenza virus infection. Generating mice with normally developed μs-deficient B cells we demonstrate that sIgM supports IgG responses by enhancing early antigen-specific B cell expansion, not by altering B cell development. Lack of FcμR expression on B cells, but not lack of Fcα/μR expression or complement activation, reduced antiviral IgG responses to the same extent as observed in μs−/− mice. B-cell-specific Fcmr−/− mice lacked robust clonal expansion of influenza hemagglutinin-specific B cells early after infection and developed fewer spleen and bone marrow IgG plasma cells and memory B cells, compared to controls. However, germinal center responses appeared unaffected. Provision of sIgM rescued plasma cell development from μs−/− but not Fcmr−/− B cells, as demonstrated with mixed bone marrow chimeric mice. Together the data suggest that sIgM interacts with FcμR on B cells to support early B cell activation and the development of long-lived humoral immunity.

Introduction

Secreted (s) IgM is the first immunoglobulin isotype produced in ontogeny as well as during early humoral immune responses. While natural IgM, derived mainly from B-1 cells, is produced spontaneously prior to encounter with foreign antigens, antigen-induced IgM derived from B-1 and B-2 cells appears only after foreign antigen exposure (1–5). Natural IgM recognizes conserved structures such as nucleic acids, phospholipids and carbohydrates in different pathogens and is required for early immune protection (4, 6–8).

Despite its often low binding-affinity to antigens, the pentameric structure of sIgM with its ten binding sites can lead to high avidity interaction with antigens and elimination of invading pathogens (9, 10). Selective IgM-deficiency has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality from various bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic infections in humans (11–13). Consistent with these findings, sIgM deficient (μs−/−) mice had significantly increased viral loads and decreased survival rates compared to wild-type controls after influenza virus infection (14, 15), as well as in response to other pathogens (5, 16–25). In addition, the absence of sIgM, derived from either B-1 or B-2 cells, significantly impaired antiviral IgG responses. Reconstitution of natural IgM deficient chimeras with IgM-containing naïve serum reversed these effects (14). Thus, sIgM is crucial for host survival from infections. However, the mechanism by which sIgM regulates B cell immunity has not been defined.

Noteworthy, μs−/− mice have multiple defects in B cell development, including decreased numbers of peripheral B cells, an unusual large number of anergic B cells, and an altered BCR repertoire (26), which may explain their increased serum levels of IgG autoantibodies and increased susceptibility to antibody-mediated autoimmune disease development (27, 28). To what extend changes in B cell development in μs−/− mice may confound a lack of sIgM per se, or the development of IgG humoral immunity to pathogens, is unclear.

It has been reported that B cells express at least three types of surface receptors that can bind IgM: The complement receptors CR1 and CR2, binding to IgM-complement complexes, the Fcα/μR which can bind both IgM and IgA, and the FcμR, which selectively binds to sIgM (29–31). This study aimed to identify the mechanisms underlying the reduced IgG responses in μs−/− mice after influenza virus infection and to identify the receptor responsible for sIgM-mediated regulation of B cell immunity. We demonstrate that mice deficient in sIgM as well as those deficient in FcμR expression by B cells lacked early B cell clonal expansion and had deficits in long-lived plasma cell development and memory B cell formation. Transfer of sIgM was able to restore normal responses in μs−/− but not FcμR−/− B cells. The data suggest that early sIgM-direct interaction with B cells via the FcμR regulates short and long-term humoral immunity to influenza infection.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Male and female 8 – 12 week old C57BL/6 (wildtype WT; CD45.2, Igh-b), B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1, Igh-b), B6.Cg-Igha Thy1a Gpi1a /J (Igh-a), and B cell-deficient (μMT) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories. Breeding pairs of B6.129S-sIgM−/− (μs−/−, CD45.2, Igh-a) mice were a kind gift from Dr. Frances Lund (University of Alabama, Birmingham). Heterozygous μs+/− mice were created by intercrossing μs−/− and C57BL/6J mice. Fcmrflx/flx mice were generated by the UC Davis Mouse Biology Program MBP) using ES cells with a targeted deletion of exon 4 of the FcμR, generated by the UC Davis MBP (32). Fcmrflx/flx mice were bred with global Cre-expressing (Cmv-Cre) mice to generate total knock out mice (Fcmr−/−), which let to the removal of the FcmR in germline. C57BL/6 (WT) mice from Jackson were used as controls. Fcmrflx/flx mice were also bred with Cd19-Cre+ mice to generate Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre+ mice with a B cell-specific deletion of the FcμR as described (32). Cre negative littermates served as controls. Fcamrflx/flx mice were obtained from The European Mouse Mutant Archive (EMMA, EM: 04668). Fcamrflx/flx mice were bred with global Cre-expressing mice to generate total knock out mice (Fcamrflx/flxCmv-Cre). C57BL/6 mice were used as control mice. All mice were kept under specific-pathogen free housing conditions, screened for the absence of 17 common mouse pathogens, in HVAC-filtered filter-top cages. Mice were euthanized by overexposure to carbon dioxide. The Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of California, Davis, approved all procedures and experiments involving animals.

Mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeras were generated by adoptively transferring equal numbers of sIgM-deficient (μs−/−, CD45.2, Igh-a), or Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre+ (CD45.2), or Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre− (CD45.2) and wild type CD45.1 (Igh-b) BM cells into two months old C57BL/6 or B cell deficient (μMT) mice, lethally irradiated by exposure to a gamma-irradiation source 24h prior to transfer. Chimeras were rested for at least 7 weeks before analysis.

Influenza virus infection

Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and infected intranasally with influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (A/PR8). Virus was grown in hen-eggs as previously outlined (Doucett et al. 2005). Each virus batch was titrated for its effect on mice. For sublethal infections, virus-doses were chosen that did not result in death and incurred no more than 20% weight loss in the infected mice. For high-dose virus challenge experiments, we used 5-times the sublethal dose of the virus.

Hemagglutination inhibition assay

Micro-hemagglutination inhibition assays using fresh chicken red blood cells (Hemostat Laboratories) and 5 HAU A/PR8 pre-incubated with serially diluted serum was done as previously reported, to determine serum HI-titers of mouse sera (3).

Passive protection assay

Sera were collected from A/PR8 infected Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre or control mice at week 10 after infection and passively transferred to C57BL/6 mice via i.v injection of 50μl serum in 150μl PBS. After 2 hours, mice were challenged intranasally with 150 PFU A/PR8. Weight of the recipients was measured at least daily after infection. Mice were euthanized when weight loss reached 30%.

Complement depletion

To deplete C57BL/6 mice of complement that is able to bind to IgM, mice were injected i.p. with 12 units cobra venom factor (CVF) twice a day. This dose of CVF was shown previously to deplete serum C3 levels by >95% for at least 4 days (33).

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions from spleens, lymph nodes, and bone marrows were stained as previously described (34). Briefly, after blocking of Fc receptors by incubation with anti-CD16/32 at 5μg/ml for 20min on ice, cells were stained with PNA-biotin (Vector Laboratories, B-1075) or HA-biotin (in-house generated) as well as the following fluorochome-conjugates: anti-biotin PE (Miltenyi Biotech), SA-Qdot 605, CD138-(PE, APC) (BD Pharmingen), CD45.1-(FITC, APC), CD45.2-PE, IgD-Cy7PE, IgM-(APC, Cy7APC), IgMa-APC, IgMb-PE, CD24-Cy55PE, CD38-FITC, CD45R-(FITC, Cy7APC), CD19-(Cy5PE, APC) (all in-house generated), and HA-PE tetramers (in-house generated, UAB). BrdU staining was done using a BrdU Flow Kit (BD Pharmingen). Dead cells were excluded by live/dead-pacblue staining (Invitrogen).

Recombinant HA fluorescent conjugates

The coding sequence of PR8 HA16-523 (accession number: P03452) was synthesized in frame with the human CD5 signal sequence upstream and the GCN4 isoleucine zipper trimerization domain downstream (GeneArt, Regensburg, Germany). This cDNA was fused in frame with either a 6XHIS tag or an AviTag at the C-terminus and cloned into the pCXpoly+ mammalian expression vector. Constructs encoding HA-6XHIS and HA-AviTag were co-transfected using 293fectin™ into FreeStyle™ 293-F Cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a 2:1 ratio. Transfected cells were cultured in FreeStyle 293 Expression Medium (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 3 days and the supernatant was recovered by centrifugation. Recombinant HA molecules were purified by FPLC using a HisTrap HP Column (GE Healthcare), and eluted with a 50mM - 250mM gradient of imidazole. Purified HA was biotinylated by addition of biotin-protein ligase (Avidity, Aurora, CO). Biotinylated proteins were then tetramerized with fluorochrome-labeled streptavidin (Prozyme, Hayward, CA). Labeled tetramers were purified by size exclusion on a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-300 column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA from different B cell subsets was isolated as previously described (32). Fcmr mRNA expression was measured using a commercial primer/probe set (Mm01302388_m1; Applied Biosystems). Relative expression was normalized to Ubc (Applied Biosystems).

Magnetic B cell enrichment

Splenic F1 μs+ and F1 μs− B cells were treated with Fc-block and were then enriched using a cocktail of biotinylated antibodies (anti-CD90.2, DX5, anti-Gr-1 with either anti-IgDa- and anti-IgMa, or with anti-IgDb and anti-IgMb) and anti-biotin Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech). Nylon filtered splenocytes were separated using autoMACS (Miltenyi Biotech). Purities of enriched F1 μs+ and F1 μs− B cells were >90% as determined by subsequent FACS analysis.

In vitro B cell proliferation assay

Magnetically-enriched B cells from F1 μs+/− were labeled with 0.5 μM CFSE in PBS at a concentration of 107cells/ml for 20 minutes at 37°C, washed twice with PBS and cultured at 2.5×105 cells/well in the presence or absence of anti-IgM 20μg/ml in 96-well round-bottom plates for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. FACS analysis was done to identify the numbers of dividing cells.

In vitro plasma cell differentiation assay

Magnetically-enriched B cells were labeled with 0.5 μM CFSE in PBS at a concentration of 107cells/ml for 20 minutes at 37°C, washed twice with PBS and then cultured at 2.5×105 cells/well in medium containing 30ng/ml IL4, 4ng/ml IL5 and 10μg/ml CD40L in 96-well round-bottom plates for 3 or 4 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. FACS analysis was done to identify the number of CFSE-low dividing cells and CD138+ plasma cells.

In vitro culture with A/PR8

Nylon filtered cells from spleens were cultured at 2.5×105 cells/well in medium containing 2,000 hemagglutinating units A/PR8 virus in 96-well round-bottom plates for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. FACS analysis was done to identify the frequencies of live, CD138+ plasma cells.

ELISA

A/PR8-binding IgM, IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2c, IgG3 levels were measured as previously described (34). Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 250 HAU of purified A/PR8 virus overnight. Following 1h incubation with blocking buffer 2-fold serially diluted serum samples in PBS were incubated for 2 hours. Antibody-binding was revealed with goat anti-mouse IgM and IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2c, IgG3 biotin (Southern Biotech) and with SA-HPO (Vector) incubated each for 1 hour. The avidity index for A/PR8 specific IgG and IgG1 binding was measured by conducting virus-specific ELISAs in the presence or absence of a 5M urea wash following antibody-binding as described previously (35).

ELISPOT

A/PR8-specific IgM and IgG secreting cells were measured as previously described (3, 34). Briefly, ELISPOT plates were coated with 500 HAU purified A/PR8 overnight, then blocked for 1h in PBS with 4% BSA. Serial dilutions of single cells from spleen, bone marrow, lung and mediastinal lymph node cells were incubated overnight at 37°C. Antibody-secreting cells (ASC) were revealed with goat anti-mouse IgM, IgG-biotin (SouthernBiotech) followed by SA-HPR (Vector Laboratories) and 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma-Aldrich).

Statistical Analysis

All data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was done using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. p < 0.05 was considered to show significantly differences, *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005.

Results

Impaired antiviral IgG responses after influenza virus infection in μs−/− mice

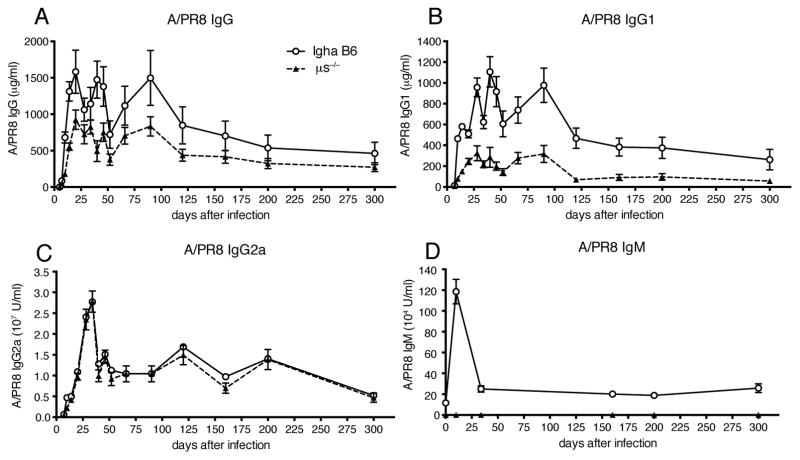

Previous studies had shown strong reductions in IgG responses against influenza virus infection in sIgM-deficient (μs−/−) mice (14, 15). To further evaluate the role of sIgM in the regulation of B cell responses to influenza, we infected μs−/− (IgHa) mice with influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (A/PR8) and compared their antiviral serum antibody titers to that of control (IgHa) mice over a nearly one-year timespan. Consistent with the previous studies, μs−/− mice showed significant reductions in antiviral IgG responses, starting at day 8 after infection (Fig. 1A). These reductions were IgG subtype specific. While virus-specific IgG1 titers were strongly reduced in μs−/− mice compared to controls (Fig. 1B), virus-specific IgG2a titers were comparable (Fig. 1C). Antiviral IgM responses peaked at day 10 after infection in the control mice and were undetectable in the (μs−/−) mice (Fig. 1D). The data confirmed that μs−/− mice are unable to rapidly mount maximal antiviral IgG responses to influenza virus infection, and demonstrated that they are unable to overcome this deficit with time.

Figure 1. Impaired antiviral IgG responses after influenza virus infection in μs−/− mice.

Graphs show mean concentrations ± SEM of influenza-specific (A) IgG, (B) IgG1, (C) IgG2a, (D) IgM in sera of μs−/− and wild type (WT) mice at indicated times after infection with influenza A/PR8 as assessed by ELISA (n = 5 mice/group). Data are representative of two independent experiments. *p<0.05 A/PR8 specific IgG and IgG1 levels by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Antiviral IgG responses are not rescued after normal development of μs− B cells

μs−/− mice have multiple defects in B cell development, resulting in reduced numbers of peripheral B cells and the appearance of a large anergic B cell population in the periphery (26). We aimed to determine next whether the decreases in IgG responses to influenza infection in the μs−/− mice were caused by effects of IgM on B cell activation and/or on B cell development. For that we generated μs−/− (IgHa) × C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) (IgHb) F1 heterozygous mice. Due to allelic exclusion, in these mice each B cell expresses IgH either from the WT (IgHb) or the μs− allele (IgHa). Thus, roughly half of B cells in the F1 mice are encoded by the IgHb locus and are able to secrete IgM, and half are encoded by the μs− (IgHa) locus, thus lack the ability to secrete IgM (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Because IgM titers in the F1 mice are comparable to that of wildtype mice, B cell development and subsets are normal including the development of μs− B cells (26). μs− B cells isolated from F1 mice responded to anti-IgM stimulation with proliferation indistinguishable to that of the μs+ B cells from the same mice, but significantly stronger than the B cells from the μs−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. 1B–C), thus further confirming that μs− B cell development and BCR signaling were rescued in sIgM-sufficient environment of the F1 mouse.

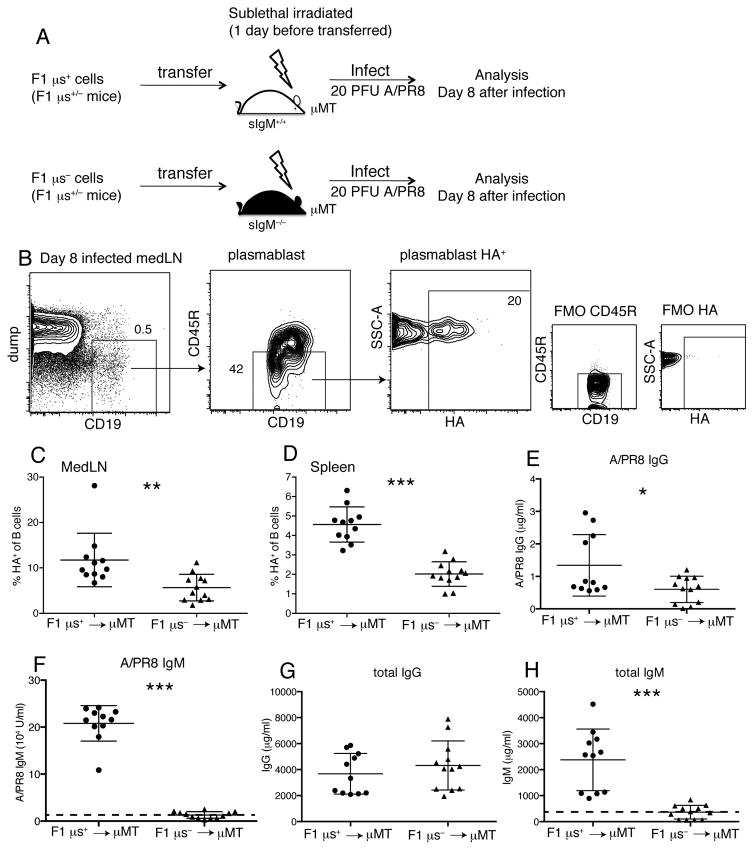

We then transferred highly enriched μs+ and μs− B cells (Supplemental Fig. 1A) from F1 mice into sublethally irradiated B cell deficient (μMT) mice, which were infected subsequently with influenza A/PR8 for 8 days (Fig. 2A). Despite their normal development and in vitro responsiveness, frequencies of HA-specific plasmablasts from the F1 μs− B cells were still lower in mediastinal lymph nodes (medLNs) and spleens than those that developed from control F1 μs+ cells (Fig. 2B–D). Similarly, the antiviral serum IgG responses derived from the F1 μs− B cells were reduced (Fig. 2E), although non-specific total IgG levels were comparable to controls (Fig. 2F), demonstrating a non-redundant function for sIgM in antiviral IgG production. As expected, mice that received F1 μs− B cells did not generate virus-specific or total serum IgM (Fig. 2G/H). Thus, the lack of sIgM during antiviral B cell response induction, not the effects of sIgM on B cell development, causes defects in B cell activation and plasma cell differentiation.

Figure 2. Reduced HA+ specific plasmablast development after influenza infection even when μs−/− B cells develop in an sIgM-sufficient environment.

(A) Sublethally-irradiated μMT mice received i.v either F1 μs+ (WT, IgMb) or F1 μs− (sIgM−/−, IgMa) cells, and were infected with 20PFU A/PR8 one day later. (B) Shown are 5% contour plots with outliers of a representative mediastinal lymph node (MedLN) sample at day 8 after infection. Boxes and arrows indicate gating strategy to identify influenza hemagglutinin (HA)-specific plasmablasts (CD19+CD45RloHA+). Fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls were used to gate on CD45R−HA+ cells. (C/D) Graphs show frequencies of HA+ plasmablasts in (C) MedLN and (D) spleen 8 days after A/PR8 infection. (E/F) Graphs show (E) A/PR8-specific IgG and (F) total IgG in chimera sera on day 8 after A/PR8 infection. (G/H) Graphs show (G) A/PR8-specific IgM and (H) total IgM in the same sera. Dashed lines in Figure 2G, H showed detection limit by ELISA. Data were combined from two independent experiments (n=11–12 mice/group). *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test

sIgM rescues IgG plasma cell differentiation by μs−/− B cells

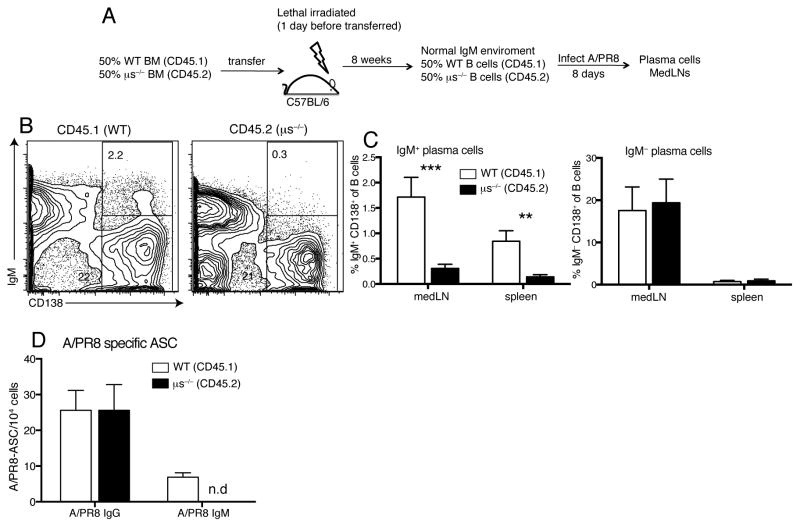

We determined next whether the defects in μs−/− plasma cell development can be rescued by provision of sIgM. For that we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras with 50% WT (CD45.1) and 50% μs−/− (CD45.2) bone marrow cells injected into lethally irradiated C57BL/6 (CD45.2) recipients (Fig. 3A). Similar to F1 μs+/− mice, the serum sIgM levels in these chimeras were comparable to control chimeras, resulting in normal B cell development of μs−/− B cells (26). Eight days following infection with influenza virus, frequencies of IgG plasma cells (Fig. 3B/C) and antiviral IgG antibody secreting cells (ASC, Fig. 3D) generated from the μs−/− B cells were also indistinguishable from that generated by WT B cells. As expected, μs−/− B cells were unable to produce sIgM or differentiate into IgM+ plasma cells (Fig. 3B–D). This was seen also in vitro, in which stimulation of F1 μs− B cells with IL4, IL5 and CD40L resulted in reduced frequencies of IgM plasma cells compared to F1 μs+ B cells (Supplemental Fig. 2A–C), while F1 μs− B cells produced comparable levels IgG spontaneously when cultured in media only and after stimulation with IL4/IL5/CD40L or LPS (Supplemental Fig. 2D). We conclude that sIgM is required for maximal IgG plasma cell generation following influenza infection.

Figure 3. Provision of sIgM rescues IgG plasma cell differentiation in μs−/− B cells.

(A) Bone marrow BM) chimeras were created by transfer of 50% WT BM (CD45.1) and 50% μs−/− BM (CD45.2) into lethally-irradiated C57BL/6 mice. Chimeras (n=4) were infected with A/PR8. (B) WT B and μs−/− B cells were identified by congenic markers CD45.1 and CD45.2, respectively. B cells originating from WT or μs−/− BM were stained for CD138+ expression. (C) Graphs show mean frequencies ± SD of IgM+CD138+ and IgM−CD138+ plasma cells of B cells derived from WT (CD45.1) and μs−/− (CD45.2) cells. (D) Shown are mean numbers ± SD of A/PR8-specific IgG and IgM ASC after WT (CD45.1) and μs−/− (CD45.2) B cells from medLNs of chimeras at day 8 after A/PR8 infection were FACS-sorted and analyzed by ELISPOT. Data are representative of two independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Effect of complement deficiency on IgG plasma cell development

IgM reportedly interacts directly with B cells via complement receptors 1 and 2 (CR1/CR2), the Fcα/μR, and the FcμR (29–31). Contradictory findings exist however, on the effects of sIgM-mediated complement activation for B cell response regulation. On the one hand, complement contributed to neutralization of influenza virus (36) and C3 depletion, or CR1 and CR2, or C4 deficiency resulted in strong reductions in humoral responses to various T-dependent antigens (37–41). On the other hand, disruption of complement binding by IgM via introduction of a point mutation in the IgM complement-binding region did not affect humoral responses (42).

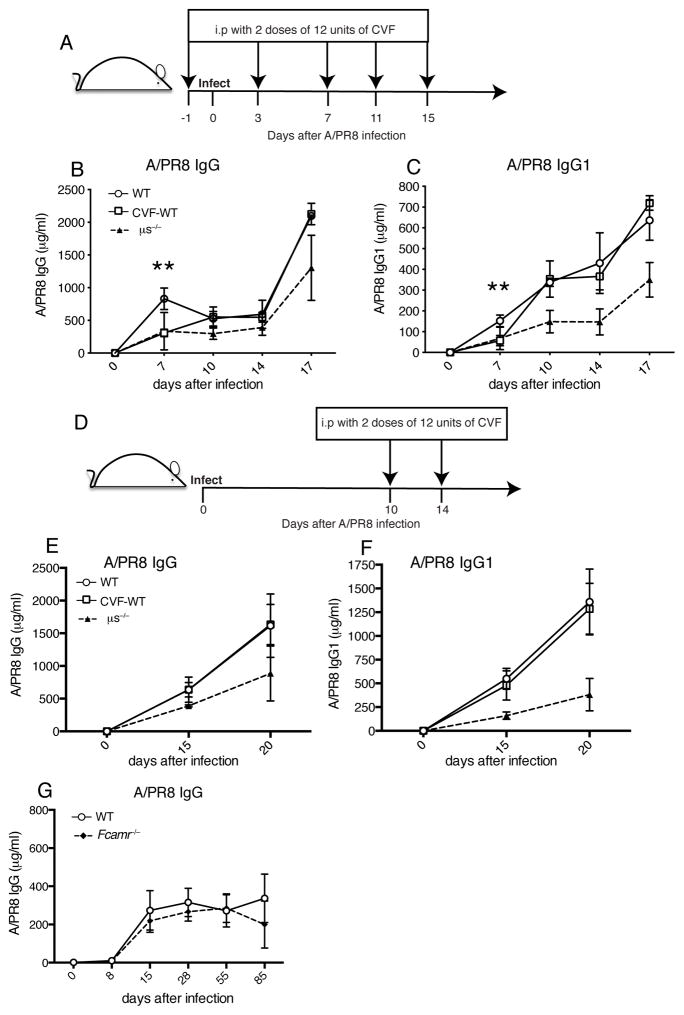

To determine whether complement-mediated binding of sIgM to B cells could be responsible for the observed immune-enhancing effects of sIgM on B cell immunity to influenza virus, we treated mice at day 1 before and days 3, 7, 11, 15 after infection with cobra venom factor (CVF), which inhibits activation of the complement cascade (Fig. 4A). While serum A/PR8 specific IgG and IgG1 titers were significantly reduced at day 7 of infection, they were not different from mock-treated mice at the subsequent time points (Fig. 4B/C). This was further confirmed by CVF treatment of mice at days 10 and 14 of infection (Fig. 4D), which had no effect on influenza-specific IgG, and IgG1 production. This is in contrast to the reductions seen in μs−/− mice at those times (Fig. 4E/F). Thus, complement-mediated binding of IgM to B cells did not appear to be responsible for the reduced IgG responses seen in μs−/− mice.

Figure 4. Neither complement depletion nor the lack of Fcα/μR results in long-term effects on antiviral IgG production.

(A) Mice were injected i.p twice with 12 units CVF at day 1 before infection, and days 3, 7, 11, 15 after infection with influenza A/PR8. (B/C) Graphs summarize the levels of (B) A/PR8 specific IgG and (C) IgG1 in sera at indicated times after infection (n=3–4 mice/group). (D) Mice were injected i.p twice with 12 units CVF at days 10 and 14 after infection with influenza A/PR8. (E/F) Levels of (E) A/PR8 specific IgG and (F) IgG1 in sera at indicated times (n=3 mice/group). (G) Mean concentrations ± SD of A/PR8 specific IgG in WT and Fcamr−/− sera after infection (n=4–6 mice/group). *p<0.05, **p<0.005 A/PR8 specific IgG and IgG1 levels between WT mice with and without CVF treatment group, and between WT and Fcamr−/− mice as assessed by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Effect of Fcα/μR deficiency on IgG responses to influenza infection

Next we determined the effects of Fcα/μR-deficiency on B cell responses to influenza infection. Mice lacking this Fc receptor (Fcamr−/−) were reported to show increased GC formation and affinity maturation to T-independent antigens (43). However, concentrations of virus-specific serum IgG were comparable in Fcamr−/− and WT mice following infection of with influenza virus, (Fig. 4G). We were unable to detect surface expression of this receptor on B cells (data not shown), possibly explaining this lack of effect. Thus, IgM-Fcα/μR interaction on B cells did not regulate IgG responses to influenza virus infection.

Reduced antiviral IgG responses in Fcmr −/− mice

The FcμR is expressed by different cell populations, and directly binds to the Fc portion of sIgM (31, 32, 44). However, studies on the effects of FcμR deficiency on antibody production and B cell differentiation have yielded contradictory results (45, 46).

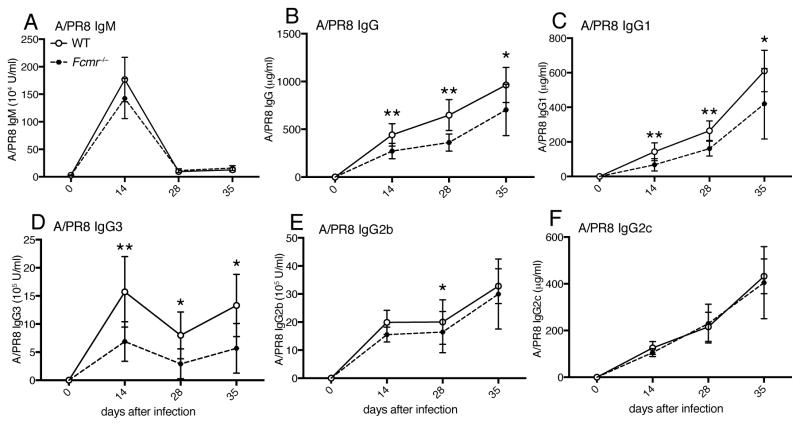

To determine whether IgM-FcμR interaction is responsible for the immune-enhancing effects of sIgM on IgG production, we infected global Fcmr−/− mice and C57BL/6 WT controls and compared their antiviral serum antibody titers over time. While antiviral serum IgM titers were similar in Fcmr−/− and WT mice (Fig. 5A), Fcmr−/− mice had reduced antiviral serum IgG titers (Fig. 5B), similar to the reductions observed in μs−/− mice (Fig. 1A). Also similar to μs−/− mice, virus-specific IgG1and IgG3 responses were most strongly affected in the Fcmr−/− mice (Fig. 5C/D), whereas reductions in virus-specific IgG2b titers were modest at best, and antiviral IgG2c responses were unaffected (Fig. 5F). The similar reductions in antiviral IgG subtype responses of μs−/− and Fcmr−/− mice suggested that sIgM-FcμR interaction enhances antiviral IgG responses.

Figure 5. Reduced antiviral IgG responses in Fcmr −/− mice.

(A) A/PR8-specific serum titers for IgM, (B) total IgG, (C) IgG1, (D) IgG3, (E) IgG2b and (F) IgG2c in Fcmr−/− and wildtype mice as assessed by ELISA at indicated times after infection with influenza A/PR/8. Shown are mean concentrations ± SD (n = 8 mice/group). Data are representative of two independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

B cell-specific deletion of FcμR expression reduces generation of passively protective immune serum

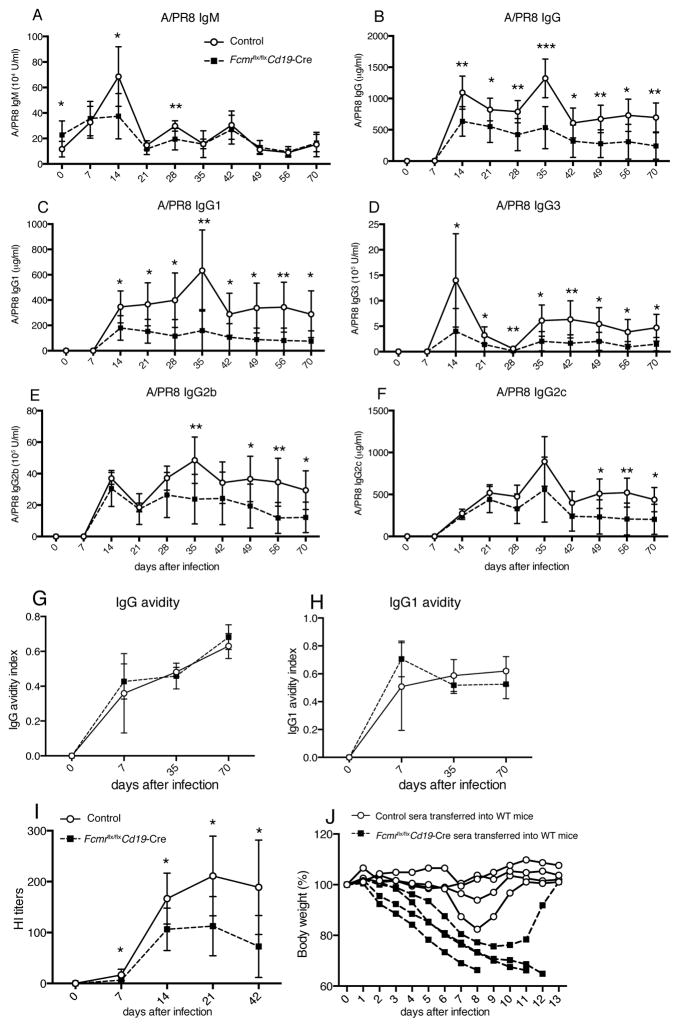

The FcμR is expressed in various leukocyte populations, including regulatory T cells, dendritic cells, granulocytes, macrophages, monocytes and B cells, the latter showing the highest surface expression (32, 46–48). To probe for potential direct effects of IgM–FcμR interaction on B cell responses, we compared antibody responses to influenza infection in B-cell-specific FcμR deficient mice (Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre+) to those of control littermates (Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre−). Antiviral IgM titers were lower in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice than in controls at days 14, and 21 after infection (Fig. 6A). Interestingly, the Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice showed similar reductions in antiviral serum IgG titers to the μs−/− and global Fcmr−/− mice (Fig. 6B), with the one difference that in the Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice all anti-A/PR8 IgG subtypes were reduced, including IgG2c (Fig. 6C–F). Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre and Fcmr−/− mice showed similar total serum IgG concentrations compared to controls, with both controls and genetically altered mice showing temporary hyperglobulenemia after infection (Supplemental Fig. 3A/B). The differences in virus-specific IgG levels were not reflected in the total IgG concentrations, as it contributed only about 0.3% total antibody to the serum (Fig. 2G/H), The avidity index of virus-binding IgG and IgG1, as measured by ELISA conducted with and without a high-salt wash after the antibody capture step, was comparable between Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice. Thus, suggesting that the lack of FcμR did not affect affinity maturation of IgG responses (Fig. 6G/H).

Figure 6. Reduced virus-specific neutralizing and protective IgG responses in influenza-infected Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice.

Shown are mean concentrations ± SD (n = 8–9 mice/group) A/PR8-specific serum titers for (A) IgM, (B) IgG, (C) IgG1, (D) IgG3, (E) IgG2b and (F) IgG2c in Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice as assessed by ELISA at indicated times after infection with influenza A/PR/8.Data are representative of two independent experiments. (G/H) Avidity index of A/PR8-specific (G) IgG and (H) IgG1 in sera of infected Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice. The avidity index was calculated as the ratio of high avidity to total serum antibodies to A/PR8 as assessed by ELISA with and without 5M urea wash. (I) Shown are hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers in sera of Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice after A/PR8 infection. (J) Sera from 70-day A/PR8-infected Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice were collected and transferred i.v into recipient C57BL/6 mice. Graph shows relative weight loss of individual recipients after a high-dose (150 PFU) influenza virus challenge. Each recipient (indicated by lines) received serum from one donor mouse. Data are representative of two independent experiments. *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Consistent with the overall reductions in antiviral IgG titers, hemagglutination inhibition titers were also greatly reduced in infected Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice compared to controls (Fig. 6I). Furthermore, serum from day 70 influenza-infected Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice could not rescue mice against body weight loss and death from high-dose influenza virus challenge after passive serum transfer, in contrast to serum from controls (Fig. 6J). Thus, the lack of FcμR in B cells caused strong defects in antiviral IgG responses, suggesting that direct FcμR-sIgM interaction on B cells regulates protective humoral immunity to influenza infection.

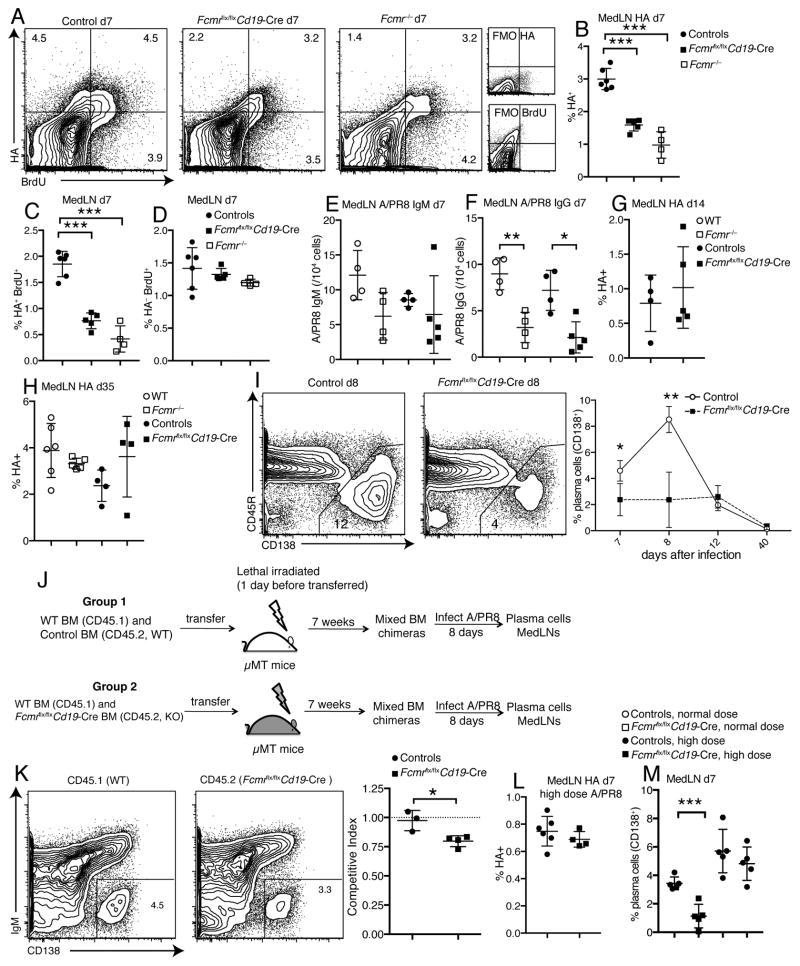

Reduced early plasma cell differentiation in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice after influenza virus infection

The reductions in serum antibody levels to influenza were correlated with reduced frequencies of HA-specific B cells in the draining lymph nodes of Fcmr−/−, and Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice at day 7 after infection, as assessed by FACS (Fig. 7A/B). This was likely due to decreased proliferation rates of HA-specific, but not non-specific B cells in the Fcmr−/− mice compared to their wild type counterparts, as measured by BrDU incorporation (Fig. 7C/D). Concomitantly, frequencies of A/PR8 IgG, but not IgM ASC were reduced in the draining lymph nodes of Fcmr−/−, and Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice at day 7 after infection compared to wild type and control Fcmr flx/flx Cd19-Cre- mice (Fig. 7E/F). At later time points, however, frequencies of HA-specific B cells recovered and were similar in all groups of mice (Fig. 7G/H). Consistent with the reductions in HA-specific B cells and ASC at early but not later time points, Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice showed strong reductions in frequencies of lymph node CD138+ plasma cells at days 7 and 8, but not at later times after infection (Fig. 7I). Together, the data suggested that the FcμR provides an early stimulation signal for virus-specific B cell activation, clonal expansion and differentiation to plasma cells.

Figure 7. Reduced early plasma cell differentiation in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice after influenza virus infection.

(A) Shown are 5% contour plots with outliers gated on live CD19+ B cells to identify BrdU+ HA-specific B cells in medLNs from control, Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and Fcmr−/− mice at day 7 after infection. BrdU was given i.p. 24h earlier. (B) Frequencies of A/PR8 HA-specific B cells in medLNs of WT, Fcmr−/−, Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice at day 7 after A/PR8 infection. (C/D) Frequencies of (C) BrdU+ A/PR8 HA-specific and (D) non-specific B cells in medLNs of WT, Fcmr−/−, Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice at day 7 after infection. (E) A/PR8-specific IgM and (F) IgG-secreting cells in medLNs of WT, Fcmr−/−, Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice at day 7 after infection as measured by ELISPOT (n=4–6 mice/group). (G/H) Frequencies of HA-specific B cells in medLNs at days (G) 14 and (H) 35 after A/PR8 infection (n=4–6 mice/group). (I) Representative 5% contour plots with outliers gated on live CD19+ B cells to identify plasma cells (CD138+) in medLNs from Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice at day 8 after infection (left panel). Graph summarizes mean frequencies ± SD of CD138+ plasma cells (n = 4–5 mice/group for each time point) (right panel). (J) Mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeras were established with 50% WT (CD45.1) and 50% Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre (CD45.2) BM; or 50% WT (CD45.1) and 50% control (CD45.2) BM and infected with A/PR8 for 8 days. (K) Shown are 5% contour plots with outliers gated on live CD19+ CD45.1+ (WT) or CD19+ CD45.2+ (Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre) cells in the same chimera, identifying plasma cells (IgM−CD138+) (left panel). Graph summarizes the plasma cell competitive index at day 8 after infection (right panel) (n=3–4 mice/group). Competitive index is the ratio of CD138+ cell frequencies of CD45.2 (Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre or control) to that of CD45.1 (WT) cells. (L) Frequencies of HA-specific B cells in medLN of Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice after high-dose infection with A/PR8 at day 7 (n=4–5 mice/group). (M) Graph summarizes mean frequencies ± SD of CD138+ plasma cells in medLN of Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice after normal dose and high dose infection with A/PR8 at day 7 (n = 5 mice/group). High dose infection was done with a 5-fold increase in PFU/mouse. *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

To determine whether the defects in early plasma cell differentiation in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice could be rescued by the presence of FcμR-expressing B cells, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras by transferring 50% WT (CD45.1) and 50% Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre (CD45.2) bone marrow cells into lethally-irradiated B cell-deficient mice. Controls received 50% WT (CD45.1) and 50% WT (CD45.2) cells (Fig. 7J). Following reconstitution, mice were infected with influenza A/PR8 and the ratios of plasma cell generation from WT and Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre B cells were determined by assessing CD45 allotype expression frequencies among CD138+ cells. The results showed that the Fcmr-deficient B cells had a significant competitive disadvantage in their ability to contribute to the plasma cell pool at day 8 of infection (Fig. 7K). Thus the data demonstrate an intrinsic requirement for FcμR expression on B cells for maximal differentiation to CD138+ plasma cells during influenza infection.

Interestingly, the reduced HA-specific B cell and plasma cell frequencies in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre compared to control mice were not observed when mice received a high-dose influenza virus infection (Fig. 7L/M). Similarly, in vitro stimulation of Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre and control B cells with IL4, IL5 and CD40L yielded similar frequencies of plasma cells (Supplemental Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the culture supernatants of Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre B cells had even higher concentrations of IgM and IgG than the controls (Supplemental Fig. 4B/C). Thus, strong inflammatory conditions and/or a high antigen dose as well as strong co-stimulatory signals can override the need for FcμR-mediated activation for maximal B cell differentiation in vivo and in vitro.

Reduced IgG plasma cell and memory B cell development in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice after influenza virus infection

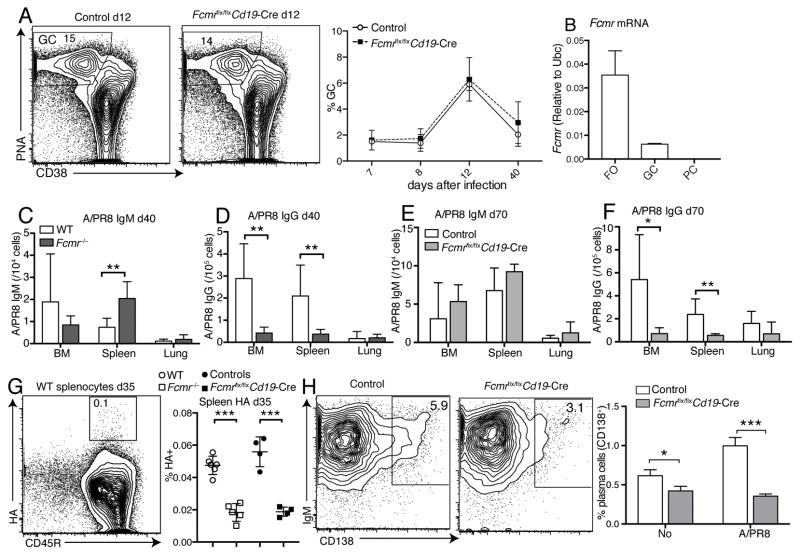

Next we determined whether the impaired B cell activation in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre also affected germinal center (GC) size or the output of long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells. FACS-analysis for PNA+ CD38lo CD19+ GC cells showed no difference in the kinetics of appearance or their numbers in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice compared to controls (Fig. 8A). This might be explained by the greatly reduced expression of the FcμR in germinal center B cells and its near absence in plasma cells (Fig. 8B), suggesting that IgM-FcμR interaction is restricted to the activation of naive B cells. Despite the normal size of the GC lymph node B cell pool, frequencies of A/PR8 IgG but not IgM ASCs were significantly lower in bone marrow and spleens, albeit not in lungs of Fcmr −/− mice, at day 40 after infection (Fig. 8C/D). Overall similar results were obtained on day 70 after infection of Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice (Fig. 8E/F). The higher levels of virus-IgM AFC observed in the spleens of these mice might be due to the increases in B-1 cell-derived spontaneous IgM secretion, noted previously (32). In summary, the lack of FcμR expression on B cells caused a significant defect in long-lived plasma cell formation after influenza virus infection.

Figure 8. Reduced long-lived IgG plasma cell and memory B cell development in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice after influenza infection.

(A) Representative 5% contour plots with outliers gated on live CD19+ B cells to identify germinal center (GC) B cells (PNA+CD38−) in medLNs of Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice at day 12 after infection (left panel). Frequencies of GC B cells in medLNs of Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice after infection with A/PR8 (n = 4–5 mice/group for each time point) (right panel). (B) FcμR mRNA expression in different B cell subsets: FO, follicular (naïve) B cells, GC, germinal center B cells, PC, plasma cells all isolated from MedLN at day 8 after influenza infection as assessed by qRT-PCR. (C) Virus-specific IgM and (D) IgG-ASC in bone marrow (BM), spleen, and lung of Fcmr−/− and wildtype mice at day 40 after infection as measured by ELISPOT (n=8 mice/group). (E) Virus-specific IgM and (F) IgG-ASC in BM, spleen, and lung of Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice at day 70 after infection as measured by ELISPOT (n=7–9 mice/group). (G) Representative 5% contour plots with outliers gated on live CD19+ B cells to identify HA-specific B cells in spleens of control (left panel) and summary of thus obtained frequencies in spleens of WT, Fcmr−/−, Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice at day 35 after A/PR8 infection (right panel) (n=4–6 mice/group). (H) Contour plots with outliers gating on live CD19+ B cells to identify plasma cells (CD138+) 3 days after in vitro culture with or without antigen (A/PR8)-stimulation of splenocytes from Fcmrflx/flxCd19-Cre and control mice infected with A/PR8 for 3 months (left panel). Mean frequencies ± SD of CD138+ plasma cells (right panel) (triplicate samples pooled from 5–6 mice/group). *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.0005 by unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Memory B cell output from GC also appeared reduced in Fcmr−/− and Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice, as suggested by the reduced frequencies of HA-specific PNA− CD45R+ B cells in spleens of these mice compared to their respective controls at day 35 of infection (Fig. 8G). Furthermore, in vitro re-stimulation of splenocytes from mice infected three months prior with influenza A/PR8, yielded reduced frequencies of plasma cells in cultures from Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice compared to controls (Fig. 8H).

We conclude that FcμR-sIgM direct interaction on B cells is required for early B cell activation, maximal IgG plasma cell responses and the generation of memory B cells after influenza virus infection.

Discussion

Here we aimed to understand the interactions of sIgM with B cells that contribute to the regulation of virus-specific B cell responses. We found that even normally developed μs−/− B cells were unable to generate maximal antiviral B cell responses to influenza infection, demonstrating a critical direct role for sIgM in B cell activation and differentiation. Lack of activated complement or a deficiency in Fcα/μR expression, two potential mechanisms of interaction between sIgM and B cells, did not result in the same reductions of antiviral IgG responses than the deficiency in sIgM. Instead, we identified FcμR expression on B cells to be critical for the development of virus-specific and protective antiviral IgG responses. sIgM-FcμR interactions seemed to support the virus-specific B cell responses by enhancing early clonal B cell expansion and the differentiation of B cells to short and long-lived plasma cells and to memory B cells..

Strikingly, the requirement for FcμR in maximal B cell response induction seemed to depend on the severity of influenza virus infection. When Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice were infected with a five-fold higher virus-dose that caused more extensive weight loss and mortality than observed with the sublethal infection doses (data not shown), the reductions in HA-specific B cell and plasma cell frequencies seen with the regular infection dose were no longer observed (Fig. 7L/M). Similarly, strong stimulation of Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice-derived B cells via CD40L and cytokines in vitro showed no overt defect in their ability to generate plasma cells in vitro (Supplemental Fig. 4). This suggests that sIgM/ FcμR interactions boost B cell responses early and potentially when antigen- and/or co-stimulatory- signals are limiting. This fits well with the known kinetics of IgM secretion after influenza infection in the draining lymph nodes, which is observed between about days 3 and day 14 of infection (3, 49).

We showed previously that FcμR-deficiency resulted in enhanced spontaneous differentiation of B-1 cells, causing increases in natural IgM levels and enhanced early control of influenza lung viral loads at day one after infection in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice (32). However, by day 5 of infection these viral load differences were no longer observed and the mice cleared the infection similar to controls (data not shown). This difference in early virus control unlikely explains the reduced frequencies of HA-specific B cells early after influenza infection, as virus infection of mixed bone marrow chimeras with bone marrow from Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre and WT cells, which had normal levels of IgM, still showed a superior ability of WT B cells to generate plasma cells, strongly suggesting that the defect in B cell-responsiveness to antigen-specific activation/differentiation signals in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice is B cell intrinsic (Fig. 7J/K).

Even though frequencies of plasma cells in medLNs, HA+ memory B cells in spleens, and long-lived plasma cells in the bone marrow were reduced in Fcmr−/− and Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice compared to WT mice and controls after influenza infection, Fcmr−/− and Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice developed normal frequencies of GC B cells compared to controls. This also correlated with normal frequencies of HA-specific B cells in the medLN and virus-specific antibody secreting cells in the lungs at and after one month of infection (Fig. 8). This was rather surprising, given that the known GC outputs, long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells, were strongly reduced in these mice. Since GC B cells and plasma cells lack FcμR expression, how the lack of early FcμR/sIgM signaling can have such long-lasting consequences for the development of responses that are thought to be dependent on GCs requires further study.

We recently identified the FcμR as a critical regulator of B cell biology, as it constrains IgM-BCR transport and cell surface expression during B cell development. Lack of FcμR expression on B cells increased IgM-BCR expression resulting in increased spontaneous GC formation, and plasma cell differentiation in Fcmr flx/flxCd19-Cre mice prior to any manipulation or infection (32). However, influenza virus infection resulted in normal GC formation and size and reduced plasma cell development, despite continued increases in IgM-BCR expression by Fcmr−/− B cells even after influenza infection (data not shown). While we cannot rule out that the changes in IgM-BCR surface expression levels may have contributed to the observed defects in B cell immunity to influenza virus infection, we believe this to be unlikely, given the hyperactive phenotype of the B cells in steady-state. Furthermore, recent studies by Jumaa and colleagues indicated that antigen-specific B cell responses to foreign antigens are mediated mainly by the IgD-BCR, not the IgM-BCR, while the IgM-BCR interact mainly with self-antigens (50). This might explain the lack of overshooting influenza-specific responses by the Fcmr−/− B cells, as their IgD-BCR levels are unaffected (32).

We suggest a working model, in which FcμR on the B cell surface binds to sIgM-virus complexes, which are then rapidly internalized (32, 44). The sIgM might either be natural IgM, which as we showed previously can bind to influenza virus (3, 14, 51), and which is generated rapidly in the regional lymph nodes by accumulating B-1 cells (3, 49). Alternatively, sIgM might be secreted by early activated virus-specific B-2 cells (3, 49). As shown, adoptive transfer of B-2 cells able to secrete IgM into an otherwise B cell-deficient environment resulted in enhanced B cell responses (Fig. 2), suggesting that the early-induced sIgM contributes to the regulation of subsequent IgG responses. Enhanced virus- uptake by follicular B cells would lead to enhance antigen presentation via MHCII, which could increase CD4 T cell - B interaction and thus T-dependent antigen-specific B cell expansion. This could explain why the absence of the FcμR resulted in reduced frequencies of virus-specific B cells at early times after infection (Fig. 7). This enhanced effect of sIgM might not be as effective when antigen-doses are high, potentially explaining why in the presence of high-dose infections, we were unable to find differences in HA-specific B cells when comparing Fcmr−/− with control mice (Fig. 7L). Further work is required to test the validity of this model. Future molecular analyses of the down-stream signaling pathways initiated by FcμR-IgM interaction are also indicated as they may help to reveal how sIgM- FcμR direct interaction on B cells can regulate effective B cell activation and antiviral IgG responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Spinner (California National Primate Research Center, UC Davis) for help with flow cytometry, Mr. Treister for FlowJo software and Dr. Frances Lund and John Bradley (University of Alabama, Birmingham) for help with generation of rHA-protein conjugates.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH AI51354, NIH AI85568, U19AI109962, the UC Davis Graduate Group in Immunology, a Vietnamese Education Fellowship to T.T.T.N., a UC Davis Chancellor’s Fellowship to N.B.

References

- 1.Hooijkaas H, Benner R, Pleasants JR, Wostmann BS. Isotypes and specificities of immunoglobulins produced by germ-free mice fed chemically defined ultrafiltered “antigen-free” diet. European journal of immunology. 1984;14:1127–1130. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830141212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haury M, Sundblad A, Grandien A, Barreau C, Coutinho A, Nobrega A. The repertoire of serum IgM in normal mice is largely independent of external antigenic contact. European journal of immunology. 1997;27:1557–1563. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi YS, Baumgarth N. Dual role for B-1a cells in immunity to influenza virus infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2008;205:3053–3064. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrenstein MR, Notley CA. The importance of natural IgM: scavenger, protector and regulator. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2010;10:778–786. doi: 10.1038/nri2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haas KM, Poe JC, Steeber DA, Tedder TF. B-1a and B-1b cells exhibit distinct developmental requirements and have unique functional roles in innate and adaptive immunity to S. pneumoniae. Immunity. 2005;23:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaw PX, Horkko S, Chang MK, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Witztum JL. Natural antibodies with the T15 idiotype may act in atherosclerosis, apoptotic clearance, and protective immunity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2000;105:1731–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearney JF, Patel P, Stefanov EK, King RG. Natural antibody repertoires: development and functional role in inhibiting allergic airway disease. Annual review of immunology. 2015;33:475–504. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgarth N. The double life of a B-1 cell: self-reactivity selects for protective effector functions. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2011;11:34–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brewer JW, Randall TD, Parkhouse RM, Corley RB. Mechanism and subcellular localization of secretory IgM polymer assembly. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:17338–17348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Czajkowsky DM, Shao Z. The human IgM pentamer is a mushroom-shaped molecule with a flexural bias. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:14960–14965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903805106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein MF, Goldstein AL, Dunsky EH, Dvorin DJ, Belecanech GA, Shamir K. Pediatric selective IgM immunodeficiency. Clinical & developmental immunology. 2008;2008:624850. doi: 10.1155/2008/624850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein MF, Goldstein AL, Dunsky EH, Dvorin DJ, Belecanech GA, Shamir K. Selective IgM immunodeficiency: retrospective analysis of 36 adult patients with review of the literature. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2006;97:717–730. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60962-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louis AG, Gupta S. Primary selective IgM deficiency: an ignored immunodeficiency. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2014;46:104–111. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumgarth N, Herman OC, Jager GC, Brown LE, Herzenberg LA, Chen J. B-1 and B-2 cell-derived immunoglobulin M antibodies are nonredundant components of the protective response to influenza virus infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:271–280. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kopf M, Brombacher F, Bachmann MF. Role of IgM antibodies versus B cells in influenza virus-specific immunity. European journal of immunology. 2002;32:2229–2236. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200208)32:8<2229::AID-IMMU2229>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond MS, Sitati EM, Friend LD, Higgs S, Shrestha B, Engle M. A critical role for induced IgM in the protection against West Nile virus infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2003;198:1853–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Couper KN, Roberts CW, Brombacher F, Alexander J, Johnson LL. Toxoplasma gondii-specific immunoglobulin M limits parasite dissemination by preventing host cell invasion. Infection and immunity. 2005;73:8060–8068. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8060-8068.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boes M, Prodeus AP, Schmidt T, Carroll MC, Chen J. A critical role of natural immunoglobulin M in immediate defense against systemic bacterial infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:2381–2386. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramaniam KS, Datta K, Quintero E, Manix C, Marks MS, Pirofski LA. The absence of serum IgM enhances the susceptibility of mice to pulmonary challenge with Cryptococcus neoformans. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:5755–5767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alugupalli KR, Gerstein RM, Chen J, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Woodland RT, Leong JM. The resolution of relapsing fever borreliosis requires IgM and is concurrent with expansion of B1b lymphocytes. Journal of immunology. 2003;170:3819–3827. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rapaka RR, Ricks DM, Alcorn JF, Chen K, Khader SA, Zheng M, Plevy S, Bengten E, Kolls JK. Conserved natural IgM antibodies mediate innate and adaptive immunity against the opportunistic fungus Pneumocystis murina. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2010;207:2907–2919. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couper KN, Phillips RS, Brombacher F, Alexander J. Parasite-specific IgM plays a significant role in the protective immune response to asexual erythrocytic stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS infection. Parasite immunology. 2005;27:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2005.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magez S, Schwegmann A, Atkinson R, Claes F, Drennan M, De Baetselier P, Brombacher F. The role of B-cells and IgM antibodies in parasitemia, anemia, and VSG switching in Trypanosoma brucei-infected mice. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4:e1000122. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajan B, Ramalingam T, Rajan TV. Critical role for IgM in host protection in experimental filarial infection. Journal of immunology. 2005;175:1827–1833. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochsenbein AF, Fehr T, Lutz C, Suter M, Brombacher F, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Control of early viral and bacterial distribution and disease by natural antibodies. Science. 1999;286:2156–2159. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen TT, Elsner RA, Baumgarth N. Natural IgM Prevents Autoimmunity by Enforcing B Cell Central Tolerance Induction. Journal of immunology. 2015;194:1489–1502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boes M, Schmidt T, Linkemann K, Beaudette BC, Marshak-Rothstein A, Chen J. Accelerated development of IgG autoantibodies and autoimmune disease in the absence of secreted IgM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:1184–1189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ehrenstein MR, Cook HT, Neuberger MS. Deficiency in serum immunoglobulin (Ig)M predisposes to development of IgG autoantibodies. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;191:1253–1258. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carroll MC. The role of complement and complement receptors in induction and regulation of immunity. Annual review of immunology. 1998;16:545–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakamoto N, Shibuya K, Shimizu Y, Yotsumoto K, Miyabayashi T, Sakano S, Tsuji T, Nakayama E, Nakauchi H, Shibuya A. A novel Fc receptor for IgA and IgM is expressed on both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic tissues. European journal of immunology. 2001;31:1310–1316. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1310::AID-IMMU1310>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubagawa H, Oka S, Kubagawa Y, Torii I, Takayama E, Kang DW, Gartland GL, Bertoli LF, Mori H, Takatsu H, Kitamura T, Ohno H, Wang JY. Identity of the elusive IgM Fc receptor (FcmuR) in humans. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2009;206:2779–2793. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen TT, Klasener K, Zurn C, Castillo PA, Brust-Mascher I, Imai DM, Bevins CL, Reardon C, Reth M, Baumgarth N. The IgM receptor FcmuR limits tonic BCR signaling by regulating expression of the IgM BCR. Nature immunology. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ni.3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quigg RJ, Kozono Y, Berthiaume D, Lim A, Salant DJ, Weinfeld A, Griffin P, Kremmer E, Holers VM. Blockade of antibody-induced glomerulonephritis with Crry-Ig, a soluble murine complement inhibitor. Journal of immunology. 1998;160:4553–4560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doucett VP, Gerhard W, Owler K, Curry D, Brown L, Baumgarth N. Enumeration and characterization of virus-specific B cells by multicolor flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2005;303:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elsner RA, Hastey CJ, Baumgarth N. CD4+ T cells promote antibody production but not sustained affinity maturation during Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Infection and immunity. 2015;83:48–56. doi: 10.1128/IAI.02471-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jayasekera JP, Moseman EA, Carroll MC. Natural antibody and complement mediate neutralization of influenza virus in the absence of prior immunity. Journal of virology. 2007;81:3487–3494. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02128-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer MB, Ma M, Goerg S, Zhou X, Xia J, Finco O, Han S, Kelsoe G, Howard RG, Rothstein TL, Kremmer E, Rosen FS, Carroll MC. Regulation of the B cell response to T-dependent antigens by classical pathway complement. Journal of immunology. 1996;157:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahearn JM, Fischer MB, Croix D, Goerg S, Ma M, Xia J, Zhou X, Howard RG, Rothstein TL, Carroll MC. Disruption of the Cr2 locus results in a reduction in B-1a cells and in an impaired B cell response to T-dependent antigen. Immunity. 1996;4:251–262. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molina H, Holers VM, Li B, Fung Y, Mariathasan S, Goellner J, Strauss-Schoenberger J, Karr RW, Chaplin DD. Markedly impaired humoral immune response in mice deficient in complement receptors 1 and 2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:3357–3361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang Y, Xu C, Fu YX, Holers VM, Molina H. Expression of complement receptors 1 and 2 on follicular dendritic cells is necessary for the generation of a strong antigen-specific IgG response. Journal of immunology. 1998;160:5273–5279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pepys MB. Role of complement in induction of antibody production in vivo. Effect of cobra factor and other C3-reactive agents on thymus-dependent and thymus-independent antibody responses. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1974;140:126–145. doi: 10.1084/jem.140.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rutemark C, Alicot E, Bergman A, Ma M, Getahun A, Ellmerich S, Carroll MC, Heyman B. Requirement for complement in antibody responses is not explained by the classic pathway activator IgM. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:E934–942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109831108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Honda S, Kurita N, Miyamoto A, Cho Y, Usui K, Takeshita K, Takahashi S, Yasui T, Kikutani H, Kinoshita T, Fujita T, Tahara-Hanaoka S, Shibuya K, Shibuya A. Enhanced humoral immune responses against T-independent antigens in Fc alpha/muR-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:11230–11235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809917106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vire B, David A, Wiestner A. TOSO, the Fcmicro receptor, is highly expressed on chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells, internalizes upon IgM binding, shuttles to the lysosome, and is downregulated in response to TLR activation. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:4040–4050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ouchida R, Mori H, Hase K, Takatsu H, Kurosaki T, Tokuhisa T, Ohno H, Wang JY. Critical role of the IgM Fc receptor in IgM homeostasis, B-cell survival, and humoral immune responses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:E2699–2706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210706109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi SC, Wang H, Tian L, Murakami Y, Shin DM, Borrego F, Morse HC, 3rd, Coligan JE. Mouse IgM Fc receptor, FCMR, promotes B cell development and modulates antigen-driven immune responses. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:987–996. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lang KS, Lang PA, Meryk A, Pandyra AA, Boucher LM, Pozdeev VI, Tusche MW, Gothert JR, Haight J, Wakeham A, You-Ten AJ, McIlwain DR, Merches K, Khairnar V, Recher M, Nolan GP, Hitoshi Y, Funkner P, Navarini AA, Verschoor A, Shaabani N, Honke N, Penn LZ, Ohashi PS, Haussinger D, Lee KH, Mak TW. Involvement of Toso in activation of monocytes, macrophages, and granulocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:2593–2598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222264110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brenner D, Brustle A, Lin GH, Lang PA, Duncan GS, Knobbe-Thomsen CB, St Paul M, Reardon C, Tusche MW, Snow B, Hamilton SR, Pfefferle A, Gilani SO, Ohashi PS, Lang KS, Mak TW. Toso controls encephalitogenic immune responses by dendritic cells and regulatory T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:1060–1065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323166111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waffarn EE, Hastey CJ, Dixit N, Soo Choi Y, Cherry S, Kalinke U, Simon SI, Baumgarth N. Infection-induced type I interferons activate CD11b on B-1 cells for subsequent lymph node accumulation. Nature communications. 2015;6:8991. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ubelhart R, Hug E, Bach MP, Wossning T, Duhren-von Minden M, Horn AH, Tsiantoulas D, Kometani K, Kurosaki T, Binder CJ, Sticht H, Nitschke L, Reth M, Jumaa H. Responsiveness of B cells is regulated by the hinge region of IgD. Nature immunology. 2015;16:534–543. doi: 10.1038/ni.3141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baumgarth N, Herman OC, Jager GC, Brown L, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Innate and acquired humoral immunities to influenza virus are mediated by distinct arms of the immune system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:2250–2255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.