Abstract

Background

Empirical evidence suggests Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) increases risk of developing alcohol use disorder (AUD). However, prospective assessment of substance use disorders (SUD) following bariatric surgery is limited.

Objective

To report SUD-related outcomes following RYGB and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB). To identify factors associated with incident SUD-related outcomes.

Setting

Ten US hospitals.

Methods

The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 is an observational cohort study. Participants self-reported past-year AUD symptoms (determined by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test), illicit drug use (cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, phencyclidine, amphetamines, or marijuana), and SUD treatment (counseling or hospitalization for alcohol or drugs) presurgery and annually postsurgery for up to seven years through January 2015.

Results

Of 2348 participants who underwent RYGB or LAGB, 2003 completed baseline and follow-up assessments (79.2% women, baseline median age 47 years, median body mass index 45.6). The year-5 cumulative incidence of postsurgery onset AUD symptoms, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment were 20.8% (95%CI, 18.5-23.3), 7.5% (95%CI, 6.1-9.1), and 3.5% (95%CI, 2.6-4.8), respectively, post-RYGB, and 11.3% (95%CI, 8.5-14.9), 4.9% (95%CI, 3.1-7.6), and 0.9% (95%CI, 0.4-2.5) post-LAGB. Undergoing RYGB vs. LAGB was associated with higher risk of incident AUD symptoms (AHR=2.08 [95%CI, 1.51-2.85]), illicit drug use (AHR=1.76 [95%CI, 1.07-2.90]) and SUD treatment (AHR=3.56 [95%CI, 1.26-10.07]).

Conclusions

Undergoing RYGB vs. LAGB was associated with twice the risk of incident AUD symptoms. One-fifth of participants reported incident AUD symptoms within 5 years post-RYGB. AUD education, screening, evaluation, and treatment referral should be incorporated in pre- and postoperative care.

Keywords: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, gastric band, obese, substance use, disorder, addiction, abuse, treatment

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for severe obesity, resulting in substantial and durable weight reduction, and improvement in or remission of obesity-related comorbidities.1 However, evidence is mounting that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) increases the risk of developing an alcohol use disorder (AUD).2-5 Pharmacokinetic studies provide evidence that RYGB, but not laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB), is associated with higher peak blood alcohol concentration, which is reached more quickly compared to presurgery status or non-surgical controls.2,5 Additionally, rodent models suggest that RYGB increases alcohol reward sensitivity via a neurobiological mechanism, independent of changes in alcohol absorption.2,5 Hypothesized pathways include changes to the ghrelin system and altered genetic expression in regions of the brain associated with reward circuitry.2,5

Studies utilizing medical records have documented over-representation of prior bariatric surgery, or specifically RYGB, among adults in substance use disorder (SUD) treatment programs.2,5,6 However, findings from longitudinal studies of AUD-related outcomes prior to and following bariatric surgery are inconsistent3-5 and few studies have long-term follow-up or evaluation of non-alcohol SUD,3,4 such that we have little understanding of whether the risk of AUD or non-alcohol SUD changes over time and the proportion of post-surgical patients that are ultimately affected. Recent literature reviews of AUD or SUD and bariatric surgery concluded there is a need for large, prospective, longitudinal studies that extend beyond two years, separate alcohol from other drug use, use standardized assessments, account for type of bariatric surgical procedure and identify risk factors for development of post-surgery AUD.3-5 This study expands our prior work7 and addresses these gaps in the literature by evaluating alcohol consumption, AUD symptoms, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment for seven years following RYGB and LAGB, and identifying factors associated with incident SUD-related outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Design and Subjects

The Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 (LABS-2) study is a prospective observational cohort study of patients at least 18 years old undergoing a first bariatric surgical procedure as clinical care by participating surgeons at ten hospitals from six clinical centers throughout the United States.8 LABS-2 had a target sample size of 2400 participants based on anticipated loss to follow-up of ≤25% and the desire to detect small effect sizes (e.g., odds ratios of at least 2.0 for categorical outcomes) with 90% power. Patients were recruited by clinical research investigators and their research coordinators between February 2006 and February 2009. The institutional review board at each center approved the protocol, and participants gave written informed consent. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00465829).

Baseline assessments were conducted by research staff independent of clinical care following clearance for surgery.9 Criteria for surgery eligibility differed by site and may have included screening for psychiatric disorders, including SUD.10,11 Participants were informed that their responses were confidential, although informed consent specified that investigators could take steps to prevent serious harm. When participants reported having at least five drinks on a typical drinking day or illicit drug use, a safety protocol was triggered to assess the need for referral. Annual follow-up assessments were conducted within six months of the surgery anniversary date for seven years or until January 31, 2015, whichever came first. Participants included in this report completed SUD-related measures at baseline and at least one assessment following RYGB or LAGB (N=2003; eFigure 1, supplement).

Measures

The same measures were collected at each assessment, excluding the six year assessment, which involved minimal data collection. Study-specific form descriptions have been previously reported.8

Alcohol consumption and AUD symptoms

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)12 is a 10-item test with well-established validity and reliability11 designed to assess alcohol use and consequences in the prior 12 months. Regular alcohol consumption was defined as drinking ≥ twice per week. An AUDIT score (range 0-40) ≥ eight suggests harmful and hazardous alcohol use, and possible dependence.13 Additionally, subsets of items indicate whether respondents experience symptoms of alcohol dependence (not being able to stop drinking once started, failing to meet normal expectations because of drinking, or needing a drink in the morning to get going), and alcohol-related harm (feeling guilt/remorse, being unable to remember, injuring someone, or eliciting concern due to drinking). Participants were categorized as having AUD symptoms (referred to as “AUD” throughout) if their AUDIT score was ≥ eight or they endorsed any symptoms of alcohol dependence or alcohol-related harm.

Illicit drug use

Participants self-reported use of the following substances, “other than as prescribed by a physician,” in the past 12 months: marijuana, amphetamines, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, and phencyclidine. Additional names of each substance were provided (e.g., hashish, pot, speed, meth, crack, LSD, sniffing glue, angel dust, PCP). Illicit drug use was defined as endorsing any such use. Opioid use was not included due to difficulties in differentiating prescribed and non-prescribed use.

SUD treatment

Participants self-reported counseling and hospital admissions for psychiatric or emotional problems in the past 12 months, and if applicable, endorsed reason(s) for treatment, including “alcohol/drug abuse.”

Incidence of SUD-related outcomes

Incidence was defined as the absence of the SUD-related outcome at baseline, in reference to the past 12 months, and presence of the SUD-related outcome at follow-up.

Other measures

Anthropometric measurements followed standardized protocols. Sociodemographics and smoking status were self-reported. Perceived social support was measured using the 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL-12) belonging domain score; a higher score (range 0-12) indicates greater support availability.14 Mental health was measured using the norm-based mental component scores from the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36); a higher score (range 0-100) indicates better functioning.15 Binge eating disorder, loss of control eating, daily anti-depressant medication use, current benzodiazepine use, past-year psychiatric counseling, and lifetime history of psychiatric hospitalization were assessed with LABS-2 forms.7;16

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). All reported P values are two-sided; P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The Pearson chi square test for categorical variables, the Cochran-Armitage test for ordinal variables, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables were used to compare 1) preoperative characteristics of LABS-2 participants in the analysis sample to those excluded (eTable 1, supplement), and 2) baseline characteristics by surgical procedure.

Longitudinal analyses performed with mixed models assumed the unstructured covariance matrix and used all available data, with control for baseline age, smoking status, and site, which were associated with missing follow-up data.17 Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the robustness of results with respect to the missing at random assumption (eAppendix 1, supplement).

Poisson mixed models with robust error variance were used to estimate and test for trends in prevalence of outcomes over time, by surgical procedure. Observed data are reported online (eTables 2a, supplement).

Further analyses were restricted to participants without the corresponding SUD-related outcome at baseline. Time to event was calculated from surgery date to the first time AUD was reported. The product-limit estimate of cumulative incidence of postsurgery AUD was determined for annual assessments. Those never reporting AUD were treated as censored observations at the end of follow-up. Because relatively few participants remaining at risk by the final time point make estimates less reliable,18 cumulative incidence by surgical procedure is reported through year-5. This analysis was repeated for components of AUD, illicit drug use and its components, and SUD treatment.

Multivariable Cox proportional-hazard models were used to identify baseline factors associated with increased risk of incident AUD, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment. Independent variables were identified in the literature7;19-27: site, surgical procedure, sex, race, baseline age, marital status, education, household income, history of psychiatric hospitalization, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, as well as baseline AUD and illicit drug use, when applicable. Ethnicity, employment status, body mass index (BMI), ISEL belonging score, SF-36 mental component summary score, binge eating, loss of control eating, anti-depressant use, benzodiazepine use, and psychiatric counseling were also considered and retained if significant. As a sensitivity analysis, this analysis was repeated after excluding data collected following reversal of the initial bariatric procedure or a new bariatric procedure.

Poisson mixed models were used to determine whether pre-to-postsurgery changes were related to postsurgery AUD, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment, with control for surgical procedure and baseline factors identified in the previous analysis. Percentage total body weight loss, change from baseline in the ISEL belonging score and the SF-36 mental component score, with control for baseline values, and postsurgery marital status, employment status, loss of control eating, anti-depressant use, benzodiazepine use, psychiatric counseling, smoking, and alcohol consumption, with consideration for baseline status (e.g., divorced vs. remained married) were considered and retained if significant. AUD and illicit drug use were also included in models in which they were not the outcome. Post-surgery binge eating and psychiatric hospitalization, and change in education and income were too rare to evaluate as independent variables.

Once independent variables were selected (in both Cox and PMM models), interactions with surgical procedure were evaluated.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the analysis sample (N=2003) and surgical groups are reported in Table 1. Participants undergoing RYGB vs. LAGB differed with respect to age, marital status, education, unemployment, income, BMI, loss of control eating, history of psychiatric hospitalization, smoking, and alcohol consumption.

Table 1. Characteristic of Adults Prior to Bariatric Surgery, by Surgical Procedure.

| Total (n = 2003)a | RYGB (n = 1481)a | LAGB (n = 522)a | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Female, No. (%) | 1586 (79.2) | 1185 (80.0) | 401 (76.8) | .12 |

| Age, Median (IQR), years | 47(37,55) | 46(37,54) | 48(38,57) | <.001 |

| Race, No. (%) | (N=1983) | (N = 1464) | (N = 519) | .12 |

| White | 1725 (87.0) | 1260 (85.1) | 465 (89.1) | |

| Black | 196 (9.9) | 154 (10.4) | 42 (8.0) | |

| Otherb | 62 (3.1) | 50 (3.4) | 12 (2.3) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, No./Total No. (%) | 92/2001 (4.6) | 69/1480 (4.7) | 23/521 (4.4) | .82 |

| Relationship status, No. (%) | (N=1993) | (N=1472) | (N=521) | .03 |

| Never married | 315 (15.8) | 244 (16.6) | 71 (13.6) | |

| Divorced, separated, or widowed | 400 (20.1) | 309 (21.0) | 91 (17.5) | |

| Married or living as married | 1278 (64.1) | 919 (62.4) | 359 (68.9) | |

| Education, No. (%) | (N=1994) | (N=1475) | (N=519) | <.001 |

| ≤ High school | 464 (23.3) | 352 (23.9) | 112 (21.6) | |

| Some college | 803 (40.3) | 628 (42.6) | 175 (33.7) | |

| ≥ College degree | 727 (36.5) | 495 (33.6) | 232 (44.7) | |

| Employment status, No. (%) | (N=1987) | (N=1467) | (N=520) | <.001 |

| Employed | 1355 (68.2) | 1006 (68.6) | 349 (67.1) | |

| Unemployed | 75 (3.8) | 65 (4.4) | 10 (1.9) | |

| Disabled | 298 (15.0) | 229 (15.6) | 69 (13.3) | |

| Other | 259 (13.0) | 167 (11.4) | 92 (17.7) | |

| Household income, US $, No. (%) | (N=1940) | (N=1434) | (N=506) | <.001 |

| < 25 000 | 354 (18.2) | 290 (20.2) | 64 (12.6) | |

| 25 000-49 000 | 505 (26.0) | 403 (28.1) | 102 (20.2) | |

| 50 000-74 999 | 456 (23.5) | 331 (23.1) | 125 (24.7) | |

| 75 000-99 999 | 312 (16.1) | 218 (15.2) | 94 (18.6) | |

| ≥ 100 000 | 313 (16.1) | 192 (13.4) | 121 (23.9) | |

| Body mass index, Median (IQR)c | 45.6(41.7,51.1) | 46.4(42.4,51.7) | 43.7(40.4,48.2) | <.001 |

| Mental health | ||||

| ISEL-12 Belonging scored | (N=1994) | (N=1742) | (N=522) | |

| Median (IQR) | 14(12,16) | 14(12,16) | 14(12,16) | .60 |

| SF-36 Mental Component Summary scoree | (N=1966) | (N=1450) | (N=516) | |

| Median (IQR) | 51.7(43.0,57.2) | 51.6(42.8,57.4) | 51.9(44.0,57.0) | .87 |

| Binge eating, No./Total No. (%) | 313/1968 (15.9) | 219/1457 (15.0) | 94/511 (18.4) | .07 |

| Loss of control eating, No./Total No. (%) | 700/1979 (35.4) | 498/1462 (34.1) | 202/517 (39.1) | .04 |

| Anti-depressant medication, No./Total No. (%) | 746/1941 (38.4) | 558/1431 (39.0) | 188/510 (36.9) | .40 |

| Benzodiazepine medication, No./Total No. (%) | 177/1952 (9.1) | 136/1442 (9.4) | 41/510 (8.0) | .35 |

| Past-year psychiatric counseling, No./Total No. (%) | 455/1984 (22.9) | 339/1468 (23.1) | 116/516 (22.5) | .78 |

| Lifetime history of psychiatric hospitalization, No./Total No. (%) | 198/1989 (10.0) | 158/1470 (10.8) | 40/519 (7.7) | .047 |

| Substance Use, past year | ||||

| Smoking, No./Total No. (%) | 238/2000 (11.9) | 194/1478 (13.1) | 44/522 (8.4) | <.01 |

| Alcohol consumption, No. (%) | (N=1995) | (N=1475) | (N=520) | <.01 |

| None | 821 (41.2) | 636 (43.1) | 185 (35.6) | |

| Any | 1043 (52.2) | 749 (50.8) | 294 (56.5) | |

| Regular (≥ 2 times/week) | 131 (6.6) | 90 (6.1) | 41 (7.9) | |

| AUD symptoms, No./Total No. (%) | 133/1988 (6.7) | 97/1469 (6.6) | 36/519 (6.9) | .79 |

| Illicit drug use, No./Total No. (%) | 84/1985 (4.2) | 64/1468 (4.4) | 20/517 (3.9) | .63 |

| SUD treatment, No./Total No. (%) | 8/1925 (0.4) | 7/1424 (0.5) | 1/501 (0.2) | .38 |

Abbreviations: AUD, Alcohol Use Disorder; lQR, interquartile range; ISEL-12, 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SF-36, Short-Form 36-item Health Survey; SUD, Substance Use Disorder.

Denominators shift between variables because of missing data.

Racial categories were combined due to small numbers: 4 Asian, 13 Native American, 3 Pacific Islander, 30 multiple races among RYBG; 1 Asian, 1 Native American, 1 Pacific Islander, 9 multiple races among LABG.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

A lower score (range 0 to12) indicates less support availability.

A lower score (range 0 to 100), indicates worse function.

SUD-related data were obtained from 78% (1684/2157), 70% (1503/2151), 67% (1434/2145), 66% (1408/2140), 67% (1418/2129), and 68% (1016/1494) of participants eligible for follow-up at years 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7, respectively.

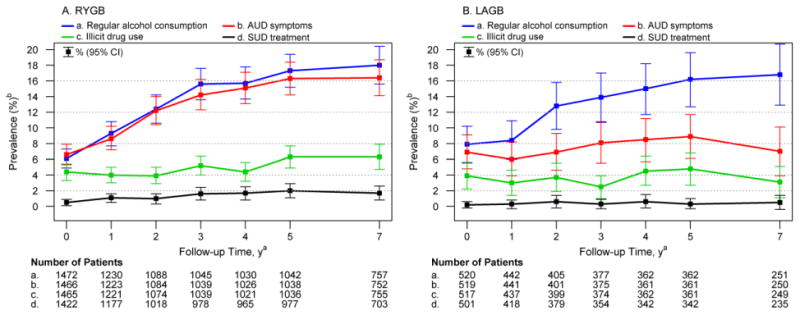

Substance use and SUD over time

Figure 1 shows the modeled prevalence of regular alcohol consumption, AUD, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment over time, stratified by surgical procedure. These and additional outcomes are reported online (eTable 2B, supplement). Following RYGB only, presurgery-to-year-7 prevalence of AUD (6.6% [95%CI, 5.3-7.9] to 16.4% [95%CI, 14.1-18.7]; P <.001) and illicit drug use (4.4% [95%CI, 3.3-5.4] to 6.3% [95%CI, 4.7-7.9]; P <.001) increased, as did any and regular alcohol consumption, subcomponents of AUD, and marijuana use (P for quadratic trends<.01), but not other drug use (P=.23) or SUD treatment (P=.18). Following LAGB there was a significant increase over time in any and regular alcohol consumption (P for quadratic trends=.01) only.

Figure 1.

Modeled Prevalence of Substance Use and Indicators of Related Problems among Adults who underwent RYGB or LAGB.

A. Among RYGB participants, there were significant increases over time in prevalence of regular alcohol consumption, AUD and illicit drug use (quadratic trends; P for all <.001) but not of SUD treatment (P =.18). B. Among LAGB participants, there was a significant increase in prevalence of regular alcohol consumption over time (quadratic trend; P =.01). There was not a significant trend in AUD (P =.09), illicit drug use (P =.33), or SUD treatment (P =.40).

Abbreviations: AUD, Alcohol Use Disorder; LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SUD, Substance Use Disorder. aAnnual assessments occurred within 6 months of the surgery anniversary date. Outcomes were not assessed at year 7. Data are based on observations until January 31, 2015; data collection ended before 432 RYGB and 177 LAGB participants were eligible for a 7 year assessment. bModels were adjusted for baseline factors related to missing follow-up data (age, smoking status and site). Observed and modeled data are reported online in eTable 2a and 2b, respectively, supplemental material.

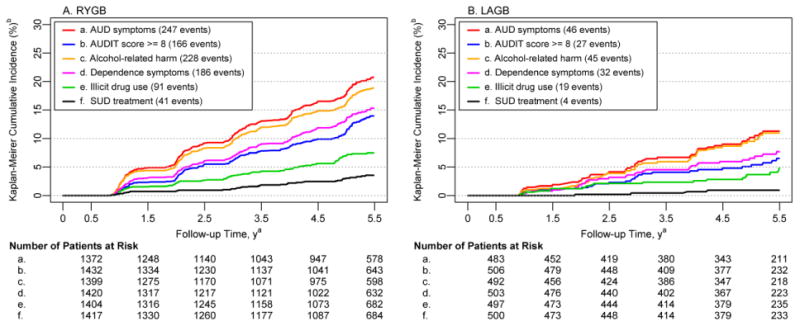

Incidence of postsurgery SUD

Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence of AUD and its subcomponents, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment over time, among participants who did not report the respective outcome at baseline. These and additional outcomes are reported online (eTable 3, supplement). The 5-year cumulative incidence of AUD, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment were 20.8% (95%CI, 18.5-23.3), 7.5% (95%CI, 6.1-9.1), and 3.5% (95%CI, 2.6-4.8), respectively, following RYGB, and 11.3% (95%CI, 8.5-14.9), 4.9% (95%CI, 3.1-7.6), and 0.9% (95%CI, 0.4-2.5), respectively, following LAGB.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Incidence of Alcohol Use Disorder Symptoms, its Subcomponents, Illicit drug use and Substance Use Disorder Treatment among Adults who underwent RYGB or LAGB.

The cumulative incidence of post-surgery SUD outcomes, among those without the specified SUD outcome in the year prior to surgery, is shown by surgical procedure, as a function of time since surgery.

Abbreviations: AUD, Alcohol Use Disorder; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; LAGB, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SUD, Substance Use Disorder.

aNumbers at risk at each time point are those who had not reported the SUD outcome since surgery and were not censored prior to or at the specified time point. Annual assessments occurred within 6 months of the surgery anniversary date. bModeled cumulative incidence with 95% CI of all SUD-related outcomes are reported in eTable 3, supplemental material.

Baseline factors associated with incident SUD-related outcomes (Table 2). Male sex, younger age, smoking, and any or regular alcohol consumption (vs. none) pre-surgery were associated with increased risk of developing AUD and illicit drug use post-surgery. Lower social support was also associated with increased risk of developing AUD, while low income, antidepressant use and a history of psychiatric hospitalization were also associated with increased risk of illicit drug use. Psychiatric counseling, a history of psychiatric hospitalization, smoking and symptoms of AUD pre-surgery were associated with increased risk of post-surgery SUD treatment. Compared to LAGB, undergoing RYGB was associated with a higher risk of incident AUD (AHR=2.08 [95%CI, 1.51-2.85]), illicit drug use (AHR=1.76 [95%CI, 1.07-2.90]) and SUD treatment (AHR=3.56 [95%CI, 1.26-10.07]). In a sensitivity analysis in which data following reversal of the initial bariatric surgical procedure (n=62) or new bariatric surgical procedure (n=64) were excluded, associations between surgical procedure and SUD-related outcomes were similar: RYGB vs. LAGB AHR=2.36 (95%CI, 1.68-3.33) for AUD, AHR=1.76 (95%CI, 1.04-2.96) for illicit drug use, and AHR=3.14 (95%CI, 1.10-8.94) for substance use treatment.

Table 2.

Pre-surgery Predictors of Incident Post-surgery AUD Symptoms, Illicit Drug Use, and SUD Treatment.

| AUD Symptoms (N=1740) | Illicit Drug Use (N=1749) | SUD Treatment (N=1817) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| No. of Participants | AHR (95%CI)a | P | No. of Participants | AHR (95%CI)a | P | No. of Participants | AHR (95%CI)a | P | |

| Sex | <001 | <.01 | .24 | ||||||

| Female | 1379 | 1 [Reference] | 1378 | 1 [Reference] | 1429 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Male | 361 | 1.74(1.34-2.24) | 371 | 1.92(1.26-2.9) | 388 | 1.49(0.77-2.88) | |||

| Age, per 10 y younger | 1736 | 1.44(1.29-1.60) | <001 | 1749 | 1.43(1.2-1.7) | <.001 | 1817 | 1.28(0.98-1.68) | 0.07 |

| Race | .71 | .39 | .32 | ||||||

| White | 1515 | 1 [Reference] | 1527 | [Reference] | 1580 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Black | 173 | 0.99(0.64-1.54) | 172 | 1.33(0.69-2.54) | 179 | 0.34(0.08-1.47) | |||

| Other | 52 | 1.30(0.69-2.44) | 50 | 1.56(0.74-3.29) | 58 | 0.59(0.08-4.44) | |||

| Marital statusc | .73 | .75 | .73 | ||||||

| Single | 611 | 1 [Reference] | 608 | 1 [Reference] | 649 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Married/living like married | 1129 | 0.95(0.73-1.24) | 1141 | 1.07(0.71-1.61) | 1168 | 1.11(0.60-2.07) | |||

| Education | .10 | .56 | .88 | ||||||

| ≤ High school | 404 | 1 [Reference] | 386 | 1 [Reference] | 410 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Some College | 708 | 0.79(0.58-1.08) | 707 | 1.25(0.78-2.02) | 734 | 1.20(0.58-2.48) | |||

| College degree | 628 | 1.05(0.77-1.42) | 656 | 1.04(0.61-1.77) | 673 | 1.11(0.51-2.41) | |||

| Household incomec | .54 | <.01 | .73 | ||||||

| ≥$25,000 | 1422 | 1 [Reference] | 1447 | 1 [Reference] | 1506 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| <$25,000 | 318 | 0.89(0.63-1.28) | 302 | 2.14(1.34-3.40) | 311 | 0.86(0.38-1.95) | |||

| ISEL-12 | b | b | |||||||

| Belonging score, per 1 point lowerd | 1740 | 1.06(1.01-1.11) | .01 | ||||||

| Antidepressant medication use | b | 0.04 9 | b | ||||||

| No | 1081 | ||||||||

| Yes | 668 | 1.49(1.01-2.21) | |||||||

| Psychiatric counseling | b | b | .01 | ||||||

| No | 1432 | 1 [Reference] | |||||||

| Yes | 385 | 2.17(1.18-3.98) | |||||||

| History of psychiatric hospitalization | .45 | .02 | <.00 1 | ||||||

| No | 1570 | 1 [Reference] | 1586 | 1 [Reference] | 1650 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Yes | 170 | 1.16(0.79-1.71) | 163 | 1.76(1.09-2.85) | 167 | 3.96(2.06-7.62) | |||

| Smoking | .04 | <.01 | .04 | ||||||

| No | 1547 | 1 [Reference] | 1557 | 1 [Reference] | 1608 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Yes | 193 | 1.41(1.02-1.96) | 192 | 2.06(1.30-3.27) | 209 | 2.07(1.04-4.12) | |||

| Alcohol consumption | <.00 1 | .03 | .37 | ||||||

| No consumption | 762 | 1 [Reference] | 716 | 1 [Reference] | 733 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Some but not regular consumption | 900 | 2.95(2.17-4.03) | 921 | 1.73(1.13-2.66) | 960 | 1.02(0.52-1.99) | |||

| Regular consumption (≥2 drinks/week) | 78 | 12.68(8.34 -19.26) | 112 | 1.99(0.82-4.84) | 124 | 1.98(0.69-5.71) | |||

| AUD | NA | .98 | .01 | ||||||

| No | 1638 | 1 [Reference] | 1693 | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| Yes | 111 | 0.99(0.49-2.02) | 124 | 2.80(1.25-6.28) | |||||

| Illicit drug use | .07 | NA | .65 | ||||||

| No | 1680 | 1 [Reference] | 1743 | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| Yes | 60 | 1.60(0.96-2.66) | 74 | 1.27(0.45-3.60) | |||||

| Surgical proceduree | <.00 1 | .03 | .02 | ||||||

| LAGB | 1284 | 1 [Reference] | 1287 | 1 [Reference] | 1338 | 1 [Reference] | |||

| RYGB | 456 | 2.08(1.51-2.85) | 462 | 1.76(1.07-2.90) | 479 | 3.56(1.26-10.07) | |||

Abbreviations: AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; AUD, Alcohol Use Disorder; ISEL-12, 12-item Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; LAGB, Laparoscopic adjustable gastric band; NA, Not applicable; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; SUD, Substance Use Disorder.

Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for other variables as indicated in this table, as well as site.

This variable was considered but not retained (P>.05). Ethnicity, employment status, body mass index, SF-36 mental component summary score, binge eating, loss of control eating, and benzodiazepine use were also considered but not retained in any models (P for all >.05).

Categories that did not differ with respect to the outcome were collapsed.

A lower score (range 0 to 12) indicates less support availability.

There were no significant interactions with surgical procedure.

Pre- to postsurgery changes associated with postsurgery SUD (Table 3). Less improvement/worsening mental health, getting divorced (vs. remaining married), starting smoking (vs. remaining a non-smoker), and starting regular drinking (vs. remaining a non-regular drinker) postsurgery were independently associated with a higher risk of postsurgery AUD, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment. Starting illicit drug use (vs. continuing no use) was also associated with a higher risk of postsurgery AUD, while post-surgery onset AUD (vs. continuing no AUD) was associated with a higher risk of illicit drug use and SUD treatment. Additionally, stopping (vs. continuing) regular drinking was associated with a lower risk of postsurgery AUD, and stopping (vs. continuing) smoking was associated with a lower risk of illicit drug use.

Table 3.

Independent Associations of Participant Characteristics and Surgical Procedure with Post-surgery AUD Symptoms, Illicit Drug Use and SUD Treatment, among Participants without the Respective Condition in the Year Prior to Surgery.

| AUD Symptoms (N=1703) | Illicit Drug Use (N=1578) | SUD Treatment (N=1772) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| ARR(95%CI)a | P | ARR(95%CI)a | P | ARR(95%CI)a | P | |

| Pre- to post-surgery change | ||||||

| SF-36 mental component summary score, per 10 points lowerb | 1.15(1.07-1.23) | <.001 | 1.24(1.10-1.40) | <.001 | 1.38(1.15-1.66) | <.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Pre- and post-surgery status | ||||||

| Marital statusc | <.01 | .01 | .048 | |||

| Got married vs. remained single | 0.66(0.43-1.00) | 1.33(079-2.24) | 0.77(0.31-1.92) | |||

| Became Single vs. remained married | 1.60(1.20-2.13) | 2.23(1.33-3.74) | 2.20(1.19-4.07) | |||

| Single vs. marriedd | 1.32(1.04-1.67) | 1.10(0.70-1.73) | 0.93(0.49-1.77) | |||

| Smoking | <.001 | <.001 | <.01 | |||

| Started vs. continued not to | 1.63(1.18-2.25) | 2.63(1.43-4.83) | 2.88(1.49-5.55) | |||

| Stopped vs. continued | 0.71(0.48-1.04) | 0.51(0.27-0.98) | 0.46(0.13-1.69) | |||

| Yes vs. nod | 1.71(1.26-2.31) | 2.76(1.73-4.42) | 2.24(1.00-5.03) | |||

| Regular alcohol consumption | <.001 | .03 | <.01 | |||

| Started vs. continued not to | 7.39(5.91-9.23) | 1.79(1.19-2.70) | 2.77(1.63-4.71) | |||

| Stopped vs. continued | 0.30(0.16-0.57) | 1.51(0.03-3.20) | 2.93(0.56-15.47) | |||

| Yes vs. nod | 13.64(9.74-19.10) | 1.14(0.50-2.64) | 1.06(0.39-2.90) | |||

| AUD symptoms | NA | <.01 | <.001 | |||

| Started vs. continued not to | 2.36(1.46-3.79) | 6.51(3.42-12.39) | ||||

| Stopped vs. continued | 1.00(0.39-2.55) | 0.21(0.02-2.11) | ||||

| Yes vs. nod | 1.65(0.72-3.78) | 6.40(2.54-16.16) | ||||

| Illicit drug use | .02 | NA | .78 | |||

| Started vs. continued not to | 1.45(1.08-1.94) | 0.75(0.31-1.78) | ||||

| Stopped vs. continued | 1.12(0.56-2.26) | 0.37(0.02-8.25) | ||||

| Yes vs. nod | 1.55(0.83-2.90) | 0.99(0.25-3.98) | ||||

Abbreviations: ARR, adjusted relative risk; AUD, Alcohol Use Disorder; NA, not applicable; SF-36, Short-Form 36-item Health Survey; SUD, Substance Use Disorder.

Poisson models with robust error variance assuming the unstructured covariance matrix, adjusted for baseline variables shown in Table 2 and other variables as indicated in this table. The following variables were also considered as independent variable but were not retained because they were not significant (P>.05): percentage weight loss from baseline, pre- to postsurgery change in the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List Belonging score, pre/postsurgery status for employment, loss of control eating, antidepressant medication, psychiatric counseling and benzodiazepine medication. There were no significant interactions with surgical procedure.

A lower score (range 0 to 100), indicates worse function.

The “married” category includes “married” and “living like married”.

Status pre- and postsurgery.

Discussion

In this observational prospective study of adults with severe obesity, the prevalence of regular drinking doubled in the seven years following both RYGB and LAGB. In contrast, the prevalence of AUD increased substantially over time following RYGB from approximately 7% presurgery to 16% at year-7, while remaining stable following LAGB between 6% and 8%. Due to differences in baseline characteristics (e.g. age, income, smoking), the RYGB vs. LAGB subgroup appeared to have higher risk for AUD. However, after excluding participants who reported the respective outcome at baseline and controlling for potential confounders, treatment with RYGB vs. LAGB was independently associated with approximately twice the risk of incident AUD and illicit drug use and nearly quadruple the risk of incident SUD treatment over seven years of follow-up. Thus our results strongly suggest that RYGB increases risk of developing AUD, using illicit drugs, and undergoing SUD treatment, and that the prevalence of AUD continues to climb for many years following RYGB.

Very few studies have longitudinally evaluated SUD-related outcomes more than two years following bariatric surgery. An exception is the Swedish Obesity Study, which began in 1987 and primarily includes surgical procedures no longer performed.3,19 Consistent with our findings, compared to non-surgical controls or banding patients, gastric bypass patients (N=265) had higher risk for incident alcohol abuse diagnoses, medium/high risk alcohol consumption, and self-reported alcohol problems over eight or more years of follow-up.19 However, the six year cumulative incidence of these outcomes was approximately 4-5%, whereas in the current report we found that one fifth of participants without AUD in the year prior to surgery reported AUD at least once within five years following RYGB. Although not all of these participants necessarily met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition) criteria for AUD28, most reported symptoms of alcohol dependence and alcohol-related harm.

Similar to previous SUD research,26,27 male sex and younger age were identified as risk factors for incident AUD and illicit drug use, while low income (<$25,000/year) was associated with incident illicit drug use only. Different psychiatric variables were predictive of incident AUD (i.e. less social support) and illicit drug use (i.e., anti-depressant medication use, history of psychiatric hospitalization), while worsening mental quality of life20, 23 and divorce24 were independently associated with all three SUD-related outcomes, as were initiating smoking and initiating regular drinking postsurgery. Initiating AUD or illicit drug use postsurgery were also associated with increased risk of the other, suggesting common causal factors.26 Contrary to the “addiction transfer” hypothesis,2 binge eating and loss of control eating were not associated with SUD-related outcomes. Weight loss was also not related to any SUD-related outcomes, which is contrary to findings by Reslan et al. in which patients with a lower percentage total body weight loss were more likely to endorse substance misuse22. Although it was outside the scope of the current study, future research should investigate the role of gut-brain neuroendocrine signaling (e.g., changes in ghrelin, as a risk factor) in risk of developing SUD following bariatric surgery.5

Incidence of SUD treatment following both procedures was much lower than the incidence of AUD symptoms, indicating treatment may be underutilized. This is troubling given the availability of a wide range of effective treatments for AUD, including brief drinking reduction interventions in medical settings, evidence-based manualized behavioral treatments (e.g., 12-step facilitation, motivational interviewing), and medications (e.g., naltrexone).29 In addition to undergoing RYGB, history of psychiatric hospitalization and psychiatric counseling in the year prior to surgery were strong predictors of incident SUD treatment, possibly reflecting greater medical surveillance or willingness to receive SUD treatment. The increase in the prevalence of regular drinking following both RYGB and LAGB may also have important implications as alcohol consumption may affect weight or induce dumping syndrome, vitamin deficiencies, dehydration, or alcoholic liver disease.11 Together, our findings strongly support the need for routine pre- and postsurgery alcohol and AUD education, screening, and evaluation, and referral for treatment when appropriate.

Illicit drug use in this study was primarily explained by marijuana use, which increased in popularity across the country during the timeframe of this study.30 However, not all relevant drugs of abuse (i.e., opioids and benzodiazepine)31 were assessed. Thus the measured prevalence and cumulative incidence of illicit drug use were likely underestimated. Additionally, determination of illicit drug use was based on self-report of any use rather than symptoms of abuse or dependence or clinical diagnosis. Thus, while RYGB vs. LAGB was significantly associated with risk of incident illicit drug use in this study, more work is needed to clarify whether bariatric surgical procedures affect risk of non-alcohol SUD.

Additional study limitations should be considered when interpreting results. First, the study did not have a non-surgical control group nor did it randomize participants to surgery. To address this source of bias, analysis evaluating associations with surgical procedure controlled for potential confounders. Still, the findings cannot necessarily be attributed to the surgery itself. Second, although participants were informed that research data were confidential, there was a potential for under-reporting of SUD-related outcomes. Under-reporting may have differed over time, but should not have differed by surgical procedure. Third, due to the unique criteria used to establish SUD-related outcomes in this study, comparisons to other studies should be made with caution. Fourth, this study excluded the gastric sleeve procedure, which although popular today,1 accounted for fewer than 5% of procedures in the LABS-2 cohort.9 Finally, because we did not measure lifetime history of SUD-related outcomes, incident cases included new-onset and recurrent cases, which might differ with respect to risk factors. Furthermore, we cannot estimate the incidence of new-onset AUD.

Notable strengths of this study are its large, geographically diverse sample, longitudinal design, standardized and detailed data collection, which allowed us to evaluate many potential risk factors, use of a validated and reliable alcohol screening tool, assessment of past-year substance use (i.e., smoking, alcohol, and illicit drugs), which may differ from current use, especially at the baseline assessment, follow-up through seven years, and high retention. These factors should make the results of our study generalizable to clinical practice. Although missing follow-up data are a concern, the initial sample size and retention rate were adequate to ensure sufficient statistical power for the primary outcome. Additionally, analyses controlled for baseline factors related to missing follow-up data and the sensitivity analysis indicated that the missing data has minimal impact on the results.

Conclusions

Among adults with severe obesity, undergoing RYGB was associated with increased risk of incident AUD symptoms, illicit drug use, and SUD treatment. Several non-surgical risk factors for post-surgery AUD and illicit drug use were also identified. Patients considering bariatric surgery should be informed of risk factors for postsurgery AUD, including type of procedure. Additionally, alcohol and AUD screening, evaluation, and referral for treatment should be incorporated into pre- and postoperative care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of support: LABS-2 was funded by a cooperative agreement by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). Grant numbers: Data Coordinating Center -U01 DK066557; Columbia-Presbyterian - U01-DK66667 (in collaboration with Cornell University Medical Center CTSC, Grant UL1-RR024996); University of Washington - U01-DK66568 (in collaboration with CTRC, Grant M01RR-00037); Neuropsychiatric Research Institute - U01-DK66471; East Carolina University – U01-DK66526; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center – U01-DK66585 (in collaboration with CTRC, Grant UL1-RR024153); Oregon Health & Science University – U01-DK66555.

Authors have no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work other than the following: Dr. A has received research grants from Covidien, Ethicon, Nutrisystem and PCORI, and consultant fees from Apollo Endosurgery. Dr. B has had an advisor role with Pacira Pharmaceuticals, has provided expert testimony for Surgical Consulting LLC, and has received travel expenses from Patient Centered outcomes research institute. Dr. C has received research grants from J & J, Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. E has received consultant fees from Enteromedics. Dr. F has received proctoring fees from Gore. Dr. G has received a research grant from Nutrisystem. Dr. H is a consultant and speaker for Medtronic and Ethicon and WL Gore and Associates.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Competing interests: All authors will complete the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Arterburn DE, Courcoulas AP. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic conditions in adults. BMJ. 2014;349:g3961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steffen KJ, Engel SG, Wonderlich JA, Pollert GA, Sondag C. Alcohol and other addictive disorders following bariatric surgery: Prevalence, risk factors and possible etiologies. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(6):442–50. doi: 10.1002/erv.2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spadola CE, Wagner EF, Dillon FR, Trepka MJ, Cruz-Munoz N, Messiah SE. Alcohol and drug use among postoperative bariatric patients: A Systematic Review of the Emerging Research and Its Implications. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(9):1582–1601. doi: 10.1111/acer.12805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L, Wu LT. Substance use after bariatric surgery: A review. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;76:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackburn AN, Hajnal A, Leggio L. The gut in the brain: the effects of bariatric surgery on alcohol consumption. Addict Biol. 2016 Aug 31; doi: 10.1111/adb.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Backman O, Stockeld D, Rasmussen F, Näslund E, Marsk R. Alcohol and substance abuse, depression and suicide attempts after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Br J Surg. 2016;103(10):1336–42. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King WC, Chen JY, Mitchell JE, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2516–2525. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belle SH, Berk PD, Courcoulas AP, et al. Safety and efficacy of bariatric surgery: Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3(2):116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belle SH, Berk PD, Chapman WH, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery-2 (LABS-2) study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9(6):926–935. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards-Hampton SA, Wedin S. Preoperative psychological assessment of patients seeking weight-loss surgery: Identifying challenges and solutions. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2015;8:263–272. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S69132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sogg S, Lauretti J, West-Smith L. Recommendations for the presurgical psychosocial evaluation of bariatric surgery patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016 May;12(4):731–49. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: An update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(2):185–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. 2nd. Geneva: WHO/MSD/MSB World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brookings JB, Bolton B. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List. Am J Community Psychol. 1988;16(1):137–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00906076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36® physical and mental health summary scales: A user's manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitchell JE, King WC, Courcoulas A, et al. Eating behavior and eating disorders in adults before bariatric surgery. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(2):215–222. doi: 10.1002/eat.22275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King WC, Chen JY, Belle SH, et al. Change in Pain and Physical Function Following Bariatric Surgery for Severe Obesity. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1362–1371. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machin D, Cheung YB, Parmar MK. Survival analysis a practical approach. 2nd. West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svensson PA, Anveden A, Romeo S, et al. Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems after bariatric surgery in the Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(12):2444–2451. doi: 10.1002/oby.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pulcini ME, Saules KK, Schuh LM. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients hospitalized for substance use disorders achieve successful weight loss despite poor psychosocial outcomes. Clin Obes. 2013;3(3-4):95–102. doi: 10.1111/cob.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wee CC, Mukamal KJ, Huskey KW, et al. High-risk alcohol use after weight loss surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):508–513. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reslan S, Saules KK, Greenwald MK, Schuh LM. Substance misuse following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49(4):405–417. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.841249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briere FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein D, Lewinsohn PM. Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(3):526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cranford JA. DSM-IV alcohol dependence and marital dissolution: Evidence from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(3):520–529. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fouladi F, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, et al. Prevalence of Alcohol and Other Substance Use in Patients with Eating Disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23(6):531–6. doi: 10.1002/erv.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(7):830–842. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iparraguirre J. Socioeconomic determinants of risk of harmful alcohol drinking among people aged 50 or over in England. BMJ Open. 2015;5(7):e007684. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Health and Human Services. Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much, A Clinician's Guide. NIH Publication No. 07–3769. Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/guide.pdf.

- 30.Grucza RA, Agrawal A, Krauss MJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA, Bierut LJ. Recent trends in the prevalence of marijuana use and associated disorders in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):300–301. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saules KK, Wiedemann A, Ivezaj V, Hopper JA, Foster-Hartsfield J, Schwarz D. Bariatric surgery history among substance abuse treatment patients: Prevalence and associated features. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(6):615–621. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.