Abstract

Objective

To develop an algorithm to identify sepsis and sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock in burn-injured patients incorporating criteria from the American Burn Association sepsis definition that possesses good test characteristics compared to ICD-9 codes and an algorithm previously validated in non-burn injured septic patients (Martin et al method).

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of consecutive patients admitted to the burn intensive care unit between January 2008 and March 2015.

Results

Of the 4761 admitted, 8.6% (n=407) met inclusion criteria, of which the case rate for sepsis was 34.2% (n=139; n=48 sepsis; n=91 sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock). For sepsis identification, the novel algorithm had an accuracy of 86.0% (95% CI 82.2% – 89.2%), sensitivity of 66.9% (95% CI 59.1% – 74.7%) and specificity of 95.9% (95% CI 93.5% – 98.3%). The novel algorithm had better discrimination (0.81, 95% CI 0.77–0.86) than the ICD-9 method (0.77, 95% CI 0.73–0.81) although this was not significant (p=0.08). For sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock, the novel algorithm plus vasopressors (0.67, 95%CI 0.63–0.72) and the ICD-9 method (0.63, 95%CI 0.58–0.68) performed equivocal (p=0.15) but the Martin method (0.76, 95% CI 0.71–0.81) had superior discrimination than other methods (p<0.01).

Conclusions

The novel algorithm is an accurate and simple tool to identify sepsis in the burn cohort with good sensitivity and specificity and equivocal discriminative ability to ICD-9 coding. The Martin method had superior discriminative ability for identifying sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock in burn-injured patients than either the novel algorithm plus vasopressors or ICD-9 coding.

Keywords: sepsis, burns, septic shock, hyperglycemia, inhalation injury

Introduction

Burn-injured patients who survive initial injuries carry a high risk of developing sepsis.(1) These patients undergo immunosuppression resulting from burn injury, predisposing them to infection.(2) Furthermore, a major cause of death in burn patients after 24 hours of injury is multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), a defining characteristic of septic shock.(2–5) In the advent of expanding research networks and electronic medical records capable of large patient registries, identifying sepsis patients accurately is crucial to understand its risk factors and outcomes in under-studied phenotypes like burn-injury. However, burn-injured patients are commonly misclassified as septic because they commonly manifest the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) response after their injury, which is not attributable to sepsis.(1, 6)

In response to this, the 2007 the American Burn Association (ABA) guidelines updated the sepsis definition in burn-injured adults and children to overcome the limitations of the SIRS criteria.(3) The ABA definition is comprised of more stringent criteria including additional physiologic parameters, hyperglycemia, thrombocytopenia, and intolerance to enteral feeding (Table 1) to address the limitations of the prior consensus definition for sepsis in critically ill patients.(7) This definition was largely derived from expert opinion or pediatric data.(3, 8, 9) The 2007 ABA recommendations are better aligned with the recently published Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) to provide better discrimination of sepsis.(4) However, the complexity of recognizing the constellation of parameters from the ABA definition is a challenge in performing epidemiologic studies and simpler methods are needed to accurately capture sepsis cases in large cohorts for research.(10) The utility of relying simply on ICD9 coding has not been evaluated in burn patients.

Table 1.

ABA Adult Sepsis Definition (3)

| ABA Sepsis Criteria |

|---|

|

In non-burn, critically ill patients, large scale epidemiologic studies have characterized the incidence, etiology and mortality rates associated with sepsis.(11, 12) These studies do not incorporate burn-injury and no data are currently available incorporating the 2007 ABA definition. In one of the largest epidemiologic studies, Martin et al validated and incorporated International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes in combination with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for organ dysfunction to identify critically ill patients with sepsis and sepsis with organ dysfunction.(11) We developed a simpler algorithm to identify sepsis in burn-injured adults comprised of ICD-9 codes for stress hyperglycemia/hyperglycemia or evidence of insulin resistance in combination with ICD-9 codes for infection or sepsis. We hypothesize that a simpler algorithm has equivalent discrimination to the 2007 ABA reference standard and has superior discrimination to ICD-9 codes alone for sepsis. Similarly, in patients with sepsis with organ dysfunction and/or septic shock, this proposed, simpler algorithm in combination with vasopressor use alone may have superior discrimination to ICD-9 codes alone or the Martin et al method.

Methods

An observational cohort of 4761 consecutive patients between January, 2008 and March, 2015 was conducted at a large, academic, tertiary care burn center. The Burn Center at Loyola University Medical Center is one of the busiest in the region, treating over 600 patients annually in the hospital. Patients with the following characteristics were included: greater than or equal to 18 years of age; total burn surface area (TBSA) ≥10% and/or an abbreviated injury scale score corresponding to at least moderate inhalational injury based on fiberoptic bronchoscopic examination by the attending burn physician (13). Patients were excluded if they were admitted to the burn ICU for a non-burn related diagnosis. If admitted multiple times during the study period, only the first encounter was included. Patients were examined daily by the attending burn physician for signs of infection, and infection control measures following best-practice guidelines were in place to minimize hospital-acquired infections and sepsis.

We designed a novel algorithm for sepsis identification a priori based on two criteria: hyperglycemia and presence of infection or sepsis. Hyperglycemia was defined incorporating claims data including ICD-9 codes for stress hyperglycemia or hyperglycemia (790.6, 790.29), or need for continuous insulin infusion greater than two hours extracted from the electronic medical record flowsheet. Hyperglycemia was added to capture cases of sepsis which were not coded as sepsis with ICD-9 codes. We excluded patients with a diagnosis of diabetes to avoid misclassification bias. Appendix A lists the ICD-9 codes used to identify infection and sepsis. These algorithms were then used to analyze the medical records for sepsis and sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock. The test characteristics of the algorithms were compared to a reference standard established through consensus of two blinded reviewers with clinical and research expertise in sepsis (MR, MA), who independently reviewed the same electronic medical records using the ABA definition (Table 1). ABA Sepsis criteria was met if at least three criteria were identified in addition to a documented infection, defined as a positive culture, a pathologic tissue source, or a clinical response to antimicrobial therapy(3). The Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) criteria were used to identify septic patients with organ dysfunction: PaO2: FiO2 ratio <400 mm Hg, platelets <150,000/mcl, bilirubin ≥1.2 mg/dL, mean arterial pressure (MAP) <70 mm Hg, and serum creatinine ≥1.2 mg/dL.(4) In cases of discordant patient assessments, a third, independent burn critical care surgeon (MM) was used as an arbitrator. Only the first encounter for sepsis was recorded. The primary objective of this study was to compare the test characteristics of the algorithms against the reference standard and provide comparisons in discrimination between the algorithms.(11)

Statistical Analysis

Interobserver reliability was measured using Cohen’s kappa coefficient. The automated algorithm’s performance was evaluated by measuring its sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy against the reference standard. Continuous variables were expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IRQ) and analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Proportions were analyzed using a chi-square test or Fischer’s exact test. Discrimination of each method was evaluated in logistic regression using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC). All the models showed adequate performance with the likelihood ratio having a p < 0.0001. The non-parametric approach of DeLong et al was used to compare the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) curves from each algorithm against the appropriate reference standard with the best area under the ROC.(14) Adjusted P values were used for the effect of multiple comparisons using Bonferroni’s method. Analysis was preformed utilizing SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and STATA version 12 (College Station, TX). Approval of this study with a waiver of consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization was provided by the institutional review board at Loyola University Medical Center.

Results

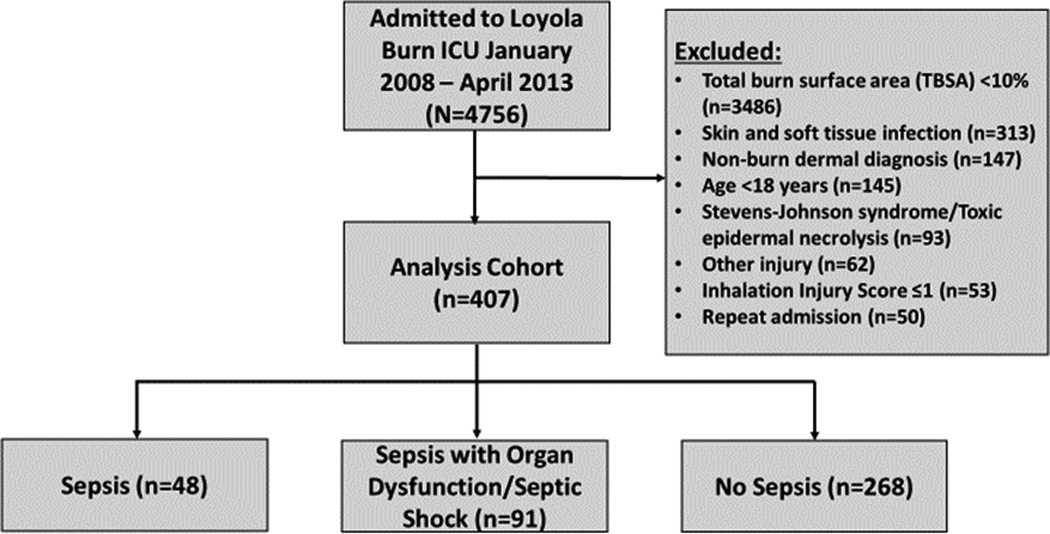

During the study period, 4761 patients were admitted to the burn ICU, of which 8.6% (n=407) met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The large majority of patients (73.2%) were excluded for TBSA <10% (n=3486; 73.2%). Of those included, the case rate for sepsis was 34.2% (n=139); 11.8% (n=48) patients were septic and 22.4% (n=91) patients experienced sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock. Patient characteristics (Table 2) were similar between patients with sepsis, sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock and without sepsis with the exception of a higher median TBSA in both sepsis groups (20.3% vs. 31.1% vs. 15%, respectively; p <0.01) and more concomitant burn and inhalation injury in both sepsis groups (22.9% vs. 26.4% vs. 8.6%, respectively; p <0.01).

Figure 1.

Study Diagram

Table 2.

Characteristics

| Characteristic | No sepsis (n=268) | Sepsis (n=48) | Sepsis with Organ Dysfunction/Septic Shock (n=91) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 47 (33 – 61) | 42.5 (33 – 55.5) | 49 (35 – 60) | 0.52 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 188 (70.2) | 37 (77.1) | 61 (67.0) | 0.47 |

| Race, white, n (%) | 171 (63.8) | 25 (52.1) | 62 (68.1) | 0.17 |

| Comorbid Conditions, n (%) |

||||

| Coronary artery disease | 18 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 9 (9.9) | 0.08 |

| Diabetes | 36 (13.4) | 5 (10.4) | 9 (9.9) | 0.62 |

| Cancer | 8 (3.0) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (3.3) | 0.92 |

| Hypertension | 94 (35.1) | 19 (39.6) | 38 (41.8) | 0.49 |

| Tobacco use | 68 (25.4) | 18 (37.5) | 29 (31.9) | 0.16 |

| Burn mechanism, n (%) | ||||

| Flame | 182 (67.9) | 39 (81.3) | 72 (79.1) | |

| Scald | 39 (14.6) | 4 (8.3) | 6 (6.6) | |

| Chemical | 9 (3.4) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 0.16 |

| Grease | 8 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Electrical | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Other | 28 (10.4) | 4 (8.3) | 10 (11.0) | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Burn | 220 (82.1) | 33 (68.8) | 58 (63.7) | |

| Burn + inhalation injury | 23 (8.6) | 11 (22.9) | 24 (26.4) | <0.01 |

| Inhalation injury | 17 (6.3) | 4 (8.3) | 8 (8.8) | |

| TBSA, median (IQR) | 15 (11.8 – 20.2) | 20.3 (15.4 – 26.6) | 31.1 (17.3 – 48.4) | <0.01 |

| Inhalation score (n=89), median (IQR) |

2 (1 – 3) | 3 (2 – 3) | 3 (2 – 3.5) | 0.28 |

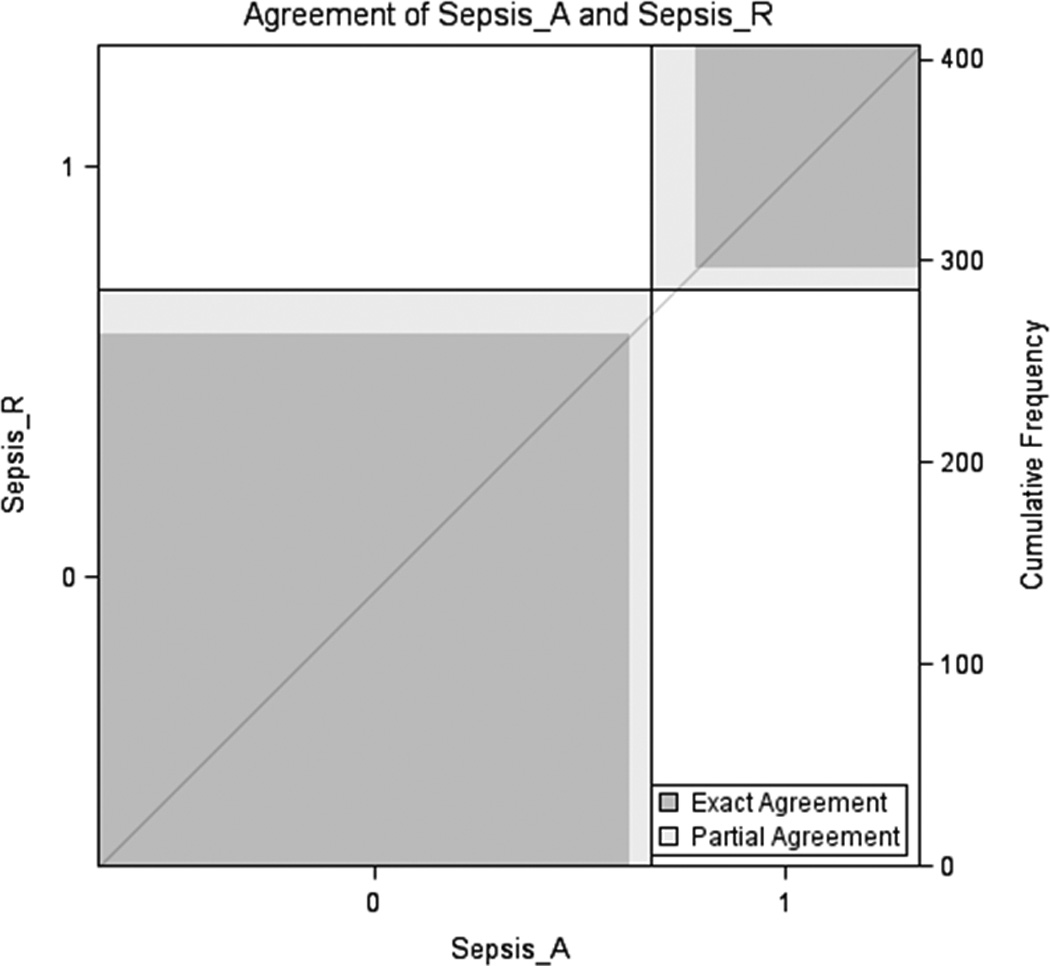

In the evaluation of sepsis cases in accordance with the ABA criteria, excellent interobserver agreement was observed with κ coefficient 0.82 (95% Confidence Interval [CI] 0.76 – 0.88, p = 0.031). Case agreement is displayed in Figure 2. Adjudication of group classification was needed in 32 cases (7.9%).

Figure 2.

Case Agreement between Reviewers

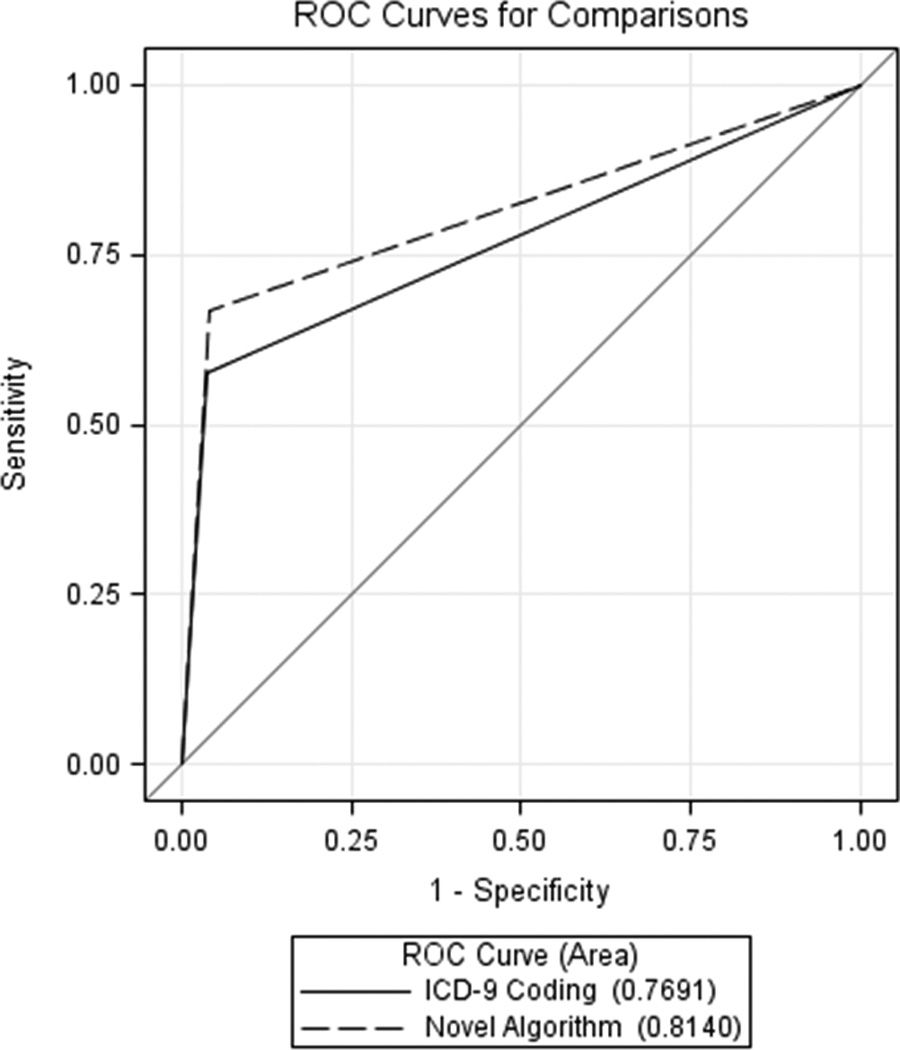

For sepsis identification, the novel algorithm had an accuracy of 86.0% (95% CI 82.2% – 89.2%), sensitivity of 66.9% (95% CI 59.1% – 74.7%) and specificity of 95.9% (95% CI 93.5% – 98.3%). The ICD-9 code method had an accuracy of 83.1% (95% CI 79.4% – 86.7%), sensitivity of 57.6% (95% CI 49.3% – 65.8%) and specificity of 96.3% (95% CI 94.0% – 98.5%). The ROCs are displayed in Figure 3. The novel algorithm had better discrimination (0.81, 95% CI 0.77–0.86) than the ICD-9 method (0.77, 95% CI 0.73–0.81) although this was only a trend towards significance (p=0.08). Hyperglycemia occurred more frequently in sepsis and sepsis with organ dysfunction/shock versus non-septic patients (79.2% vs. 74.7% vs. 20.7%, respectively; p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic for Sepsis Identification

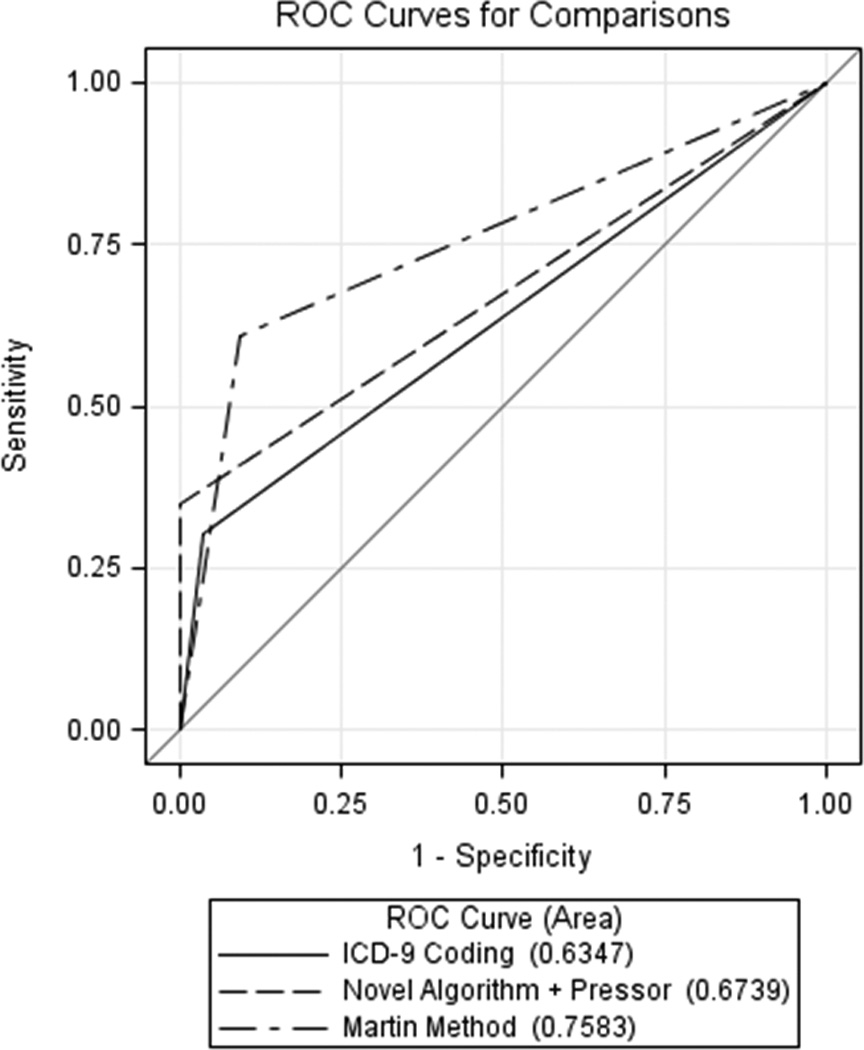

For sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock identification, the novel algorithm plus vasopressors >4 hours had an accuracy of 85.3% (95% CI 81.8% – 88.7%), sensitivity of 34.8% (95% CI 25.1% – 44.5%) and specificity of 100% (95% CI 100% – 100%). The ICD-9 code method had an accuracy of 81.6% (95% CI 77.8% – 85.3%), sensitivity of 30.4% (95% CI 21.0% – 39.8%) and specificity of 96.5% (95% CI 94.5% – 98.5%). The Martin method had an accuracy of 84.0% (95% CI 80.5% – 87.6%), sensitivity of 60.9% (95% CI 50.9% – 70.8%) and specificity of 90.8% (95% CI 87.7% – 94.0%). The ROCs for these methods are displayed in Figure 4. The novel algorithm plus vasopressors >4 hours (0.67, 95%CI 0.63–0.72) and the ICD-9 method (0.63, 95%CI 0.58–0.68) performed equivocal (p=0.15) but the Martin method (0.76, 95% CI 0.71–0.81) had superior discrimination than other methods (p<0.01) in the identification of burn-injured patients with sepsis with organ dysfunction and/or septic shock.(11)

Figure 4.

Receiver Operating Characteristics for Sepsis with Organ Dysfunction/Septic Shock Identification

Discussion

We demonstrated a novel algorithm incorporating key elements of the ABA sepsis criteria had better accuracy than traditional methods for identification of sepsis. However, for identification of sepsis with organ dysfunction and/or septic shock, the Martin method had the best test characteristics and can be applied to burn-injured critically ill patients. In patients arriving to our large referral burn center with at least 10% TBSA burn-injury, about one-third developed sepsis and the large majority of the septic patients had organ dysfunction or shock. The high rate of sepsis development in burn-injury requires an efficient method that carries good test characteristics and is validated in order to perform future outcomes research and epidemiologic studies. Previous epidemiology studies in septic patients have not included burn-injured patients and epidemiologic data in this cohort are limited given the difficulty in identifying the constellation of ABA sepsis criteria and ubiquitousness of SIRS criteria.(3, 15) This study aimed to examine novel methods that avoided misclassification bias due to the prevalence of SIRS in burn-injured patients and accurately identified burn-injured patients with sepsis. (11, 12) Our study has important implications as it may be applied in future epidemiologic and outcome studies in burn and sepsis.

Our algorithm was comprised of ICD-9 codes for infection or sepsis combined with the presence of hyperglycemia. We selected these variables a priori as infection may be coded more frequently than sepsis in burn-injured patients. Our evaluation using a reference standard with physician chart review shows how reliable these administrative data are for classifying cases. The second criterion, hyperglycemia, was determined according to ICD-9 coding or use of continuous insulin infusion for at least two hours. Hyperglycemia is a common complication in burn injury and is predictive of sepsis.(4, 6, 16) A recent study found that 64% of burn patients had some degree of glucose intolerance upon discharge from the burn ICU.(16) Within this cohort, incidence of sepsis was higher in the glucose intolerance/impaired fasting glucose group compared to those with normal glucose tolerance (35% vs. 18%). Another study demonstrated that maximum insulin drip rate was predictive of bacteremia in burn-injured patients.(10)

Our study demonstrates that both the novel algorithm and sepsis ICD-9 code had good test statistics against the gold standard. While the novel algorithm had better discrimination compared to ICD-9 codes, there was no statistical difference (p=0.08). Thus, both methods could be potentially useful and should be validated in future studies.

The Martin method for identification of sepsis had superior discriminative ability for identifying sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock in burn-injured patients than either the novel algorithm plus vasopressor use or ICD-9 coding.(11) Our novel algorithm had a specificity of 100% in this population; thus, it may be helpful in ruling in septic burn-injured patients. The Martin method has not been previously used in a burn-injured population. Our study suggests that is can be utilized to identify sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock in burn-injured patients as well.

Our study is limited in its retrospective, single center design. Future studies are needed to externally validate our findings at other burn centers. Additionally, the algorithms studied utilized ICD-9 data, which are being replaced with ICD-10 criterion so future studies should incorporate both ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to identify a feasible and practical method for implementation in an electronic health record system to identify sepsis in burn-injured patients.

Conclusion

The novel algorithm for identifying sepsis in burn-injured patients had good sensitivity and specificity and equivocal discriminative ability to ICD-9 coding. In burn-injured patients, the Martin method had superior discriminative ability for identifying sepsis with organ dysfunction/septic shock in burn-injured patients than either the novel algorithm plus vasopressor use or ICD-9 coding. The novel algorithm is an accurate and simple tool to identify sepsis in the burn cohort. The external validation of this tool is necessary before its implementation to examine the epidemiology of sepsis in burn-injured adults.

Acknowledgments

funding:

Majid Afshar is currently receiving a grant (K23AA024503) from the NIH.

Elizabeth Kovacs is currently receiving a grant (R01GM115257) from the NIH.

Appendix A: ICD-9 Codes for Infection and Sepsis

| Condition | Code |

|---|---|

| Sepsis | 995.91 |

| Sepsis with acute organ dysfunction sepsis with multiple organ dysfunction Severe sepsis |

995.92 |

| Bacteremia | 790.7 |

| Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection | 999.31 |

| Pneumonia | 482, 486 |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 997.31 |

| Posttraumatic wound infection | 958.3 |

| Urinary tract infection/urosepsis | 599.0 |

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

The remaining authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Hidalgo F, Mas D, Rubio M, et al. Infections in critically ill burn patients. Medicina intensiva / Sociedad Espanola de Medicina Intensiva y Unidades Coronarias. 2016;40(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Church D, Elsayed S, Reid O, et al. Burn wound infections. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2006;19(2):403–434. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.403-434.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenhalgh DG, Saffle JR, Holmes JHt, et al. American Burn Association consensus conference to define sepsis and infection in burns. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2007;28(6):776–790. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181599bc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) Jama. 2016;315(8):801–810. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu G, Xiao Y, Wang C, et al. Risk Factors for Acute Kidney Injury in Patients With Burn Injury: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2016 doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann-Salinas EA, Baun MM, Meininger JC, et al. Novel predictors of sepsis outperform the American Burn Association sepsis criteria in the burn intensive care unit patient. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2013;34(1):31–43. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31826450b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bone RC, Sibbald WJ, Sprung CL. The ACCP-SCCM consensus conference on sepsis and organ failure. Chest. 1992;101(6):1481–1483. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Housinger TA, Brinkerhoff C, Warden GD. The relationship between platelet count, sepsis, and survival in pediatric burn patients. Arch Surg. 1993;128(1):65–66. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420130073011. discussion 66–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf SE, Jeschke MG, Rose JK, et al. Enteral feeding intolerance: an indicator of sepsis-associated mortality in burned children. Arch Surg. 1997;132(12):1310–1313. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430360056010. discussion 1313–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hogan BK, Wolf SE, Hospenthal DR, et al. Correlation of American Burn Association sepsis criteria with the presence of bacteremia in burned patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2012;33(3):371–378. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182331e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348(16):1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Critical care medicine. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endorf FW, Gamelli RL. Inhalation injury, pulmonary perturbations, and fluid resuscitation. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2007;28(1):80–83. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0B013E31802C889F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mokline A, Garsallah L, Rahmani I, et al. Procalcitonin: a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of sepsis in burned patients. Annals of burns and fire disasters. 2015;28(2):116–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rehou S, Mason S, Burnett M, et al. Burned Adults Develop Profound Glucose Intolerance. Critical care medicine. 2016;44(6):1059–1066. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]