Sedated transoral endoscopy (sEGD) remains the conventional and most commonly utilized diagnostic tool to directly visualize the upper gastrointestinal tract for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. While this has become a relatively routine procedure with a favorable risk profile, it is associated with complications (albeit at a low rate) that may be prohibitive in certain high-risk populations. In addition it is also expensive, making it a less suitable tool for large-scale applications such as screening for reflux complications such as Barrett’s esophagus or complications of cirrhosis such as varices. The potential use of unsedated transnasal endoscopy (uTNE) for these conditions is attractive if proven to be acceptable, safe, and accurate. Recent data suggest that uTNE can be a safe and accurate alternative to sEGD for these indications (Table 1).

Table 1.

Indications for unsedated transnasal endoscopy

| 1. Diagnostic endoscopy in a patient at high risk for endoscopic sedation-related complications |

| 2. Placement of nasoenteric feeding tubes |

| 3. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal varices |

| 4. Evaluation of dysphagia, eosinophilic esophagitis |

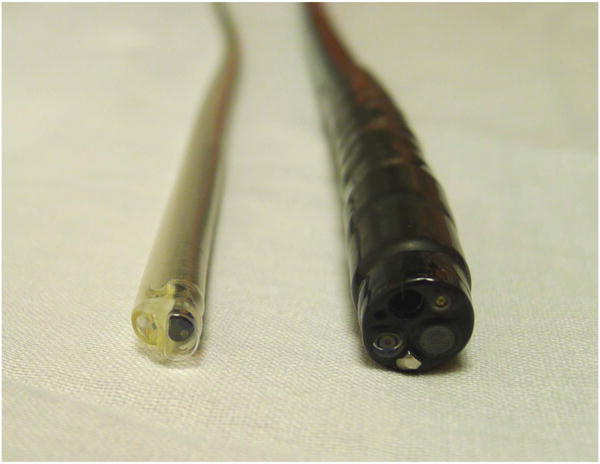

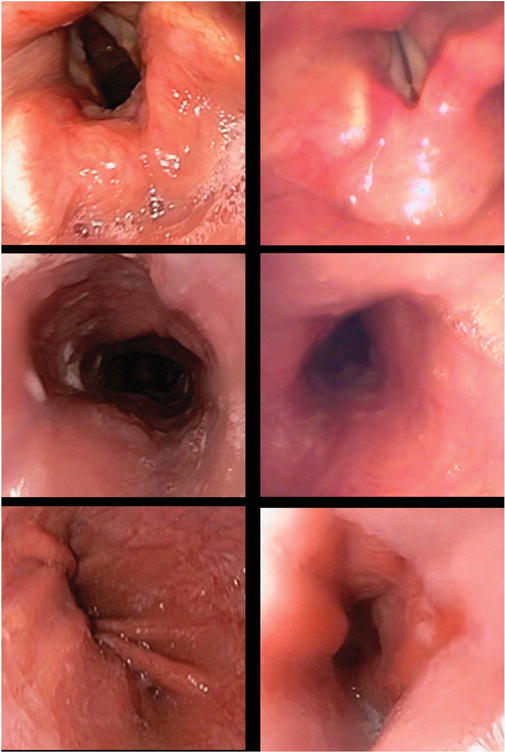

Commercially available transnasal endoscopes are listed in Table 2. Transnasal endoscopes are slimmer than conventional diagnostic endoscopes with shaft diameters ranging from 5–6 mm (Figure 1). Their working channel (if available) is smaller (2 mm in diameter) and hence cannot accommodate standard-sized biopsy forceps or other through-the-scope tools. Pediatric biopsy cables can be advanced through the therapeutic channel to obtain biopsies if needed. While some transnasal endoscopes have both right-left and up-down controls, those slimmer than 5 mm only have an up-down control (Figure 2). Most of these endoscopes are of adequate length to examine the stomach and proximal duodenum and need conventional light sources and disinfection after use. Recently an esophagoscope (65 cm in length) has been introduced which is covered with a disposable sheath (Endosheath, Cogentix Medical, Minnetonka, MN), and is available in two configurations: with or without a biopsy channel. This sheath protects the endoscope from coming into contact with body fluids and can be discarded after use. The endoscope can then be disinfected with sopropyl alcohol wipes and reutilized with another sheath, without undergoing conventional disinfection. While the imaging in this endoscope, which is generated by a charge-coupled device, is not high definition, it appears to be adequate and comparable to conventional endoscopy from a diagnostic standpoint as shown in recent trials (Figure 3). A disposable capsule attached to a shaft is also commercially available for visualization of the esophagus and stomach (E.G.Scan II, Intromedic, Seoul, Korea). It is connected to a controller and processor. Both these devices that do not require conventional disinfection make mobile or in office examinations a possibility.

Table 2.

Commercially available transnasal endoscopes/devices

| Manufacturer/model | Angulation | Field of view (degree) | Shaft diameter (mm) | Accessory channel diameter (mm) | Working length (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujinon (Wayne, NJ) | |||||

| EG-530N | 210 up/90 down 100 left/100 right | 120 | 5.9 | 2 | 1,100 |

| EG-530NP | 210 up/120 down | 120 | 4.9 | 2 | 1,100 |

| EG-270N5 | 210 up/120 down 100 left/100 right | 120 | 5.9 | 2 | 1,100 |

| Pentax (Montvale, NJ) | |||||

| EG 1580K | 210 up/120 down | 140 | 5.1 | 2 | 1,050 |

| EG 1690K | 210 up/120 down 120 left/120 right | 120 | 5.4 | 2 | 1,100 |

| EG 1870K | 210 up/120 down 120 right/120 left | 140 | 6 | 2 | 1,050 |

| EE 1580K | 210 up/120 down | 140 | 5.5 tip, 5.1 shaft | 2 | 600 |

| FG-16V | 180 up/180 down 160 right/160 left | 125 | 5.3 | 2 | 925 |

| Olympus (Center Valley, PA) | |||||

| GIF-XP190N | 210 up/90 down 100 left/100 right | 140 | 5.8 | 2.2 | 1,100 |

| GIF N180 | 210 up/120 down | 120 | 4.9 | 2 | 1,100 |

| PEF-V | 180 up/130 down | 120 | 5.3 | 2 | 650 |

| Vision Sciences (Cogentix Medical, Minnetonka, MN) | |||||

| TNE-5000 | 145 up/215 down | 120 | 4.7/5.4 (oval shaft) 4.7/5.8 (oval shaft) |

1.5 2.1 |

650 |

| Intromedic (Seoul, Korea) | |||||

| E.G.Scan II | 160 up/160 down | 125 | 6.5 mm (capsule) 3.5 mm (shaft) |

NA | 1,087 |

NA, not applicable.

Figure 1.

Relative diameters of a standard gastroscope and transnasal endoscope inside a protective Endosheath with a biopsy channel.

Figure 2.

Transnasal endoscope with Endosheath (TNE-5000) with up-down only controls.

Figure 3.

Comparative images from conventional endoscopy (left column) and transnasal endoscopy (right column). Row 1 shows the laryngeal structures, row 2 shows tubular mid-esophagus, and row 3 shows the gastroesophageal junction.

PROCEDURE

The first step is to obtain adequate local anesthesia of the nasopharynx. This can be done with either a topical spray of lidocaine with a vasoconstrictor such as oxymetazoline or by introducing a pretreatment swab coated with topical anesthetic gel into the nasal passage for 5 min before introduction of the endoscope. Either nasal passage can be used after documenting the absence of any anatomic abnormality. The procedure can be done with the patient in the left lateral decubitus or seated upright position. The endoscope is lubricated, introduced into the nasal passage, advanced along the floor of the nasopharyngeal space or between the middle and inferior turbinate. Following visualization of the usual pharyngeal and laryngeal landmarks, the endoscope is advanced into the esophagus under vision. Following esophageal intubation, the exam is completed in the same manner as conventional endoscopy.

ADVANTAGES OF uTNE

The advantages associated with uTNE over sEGD include the following: greater patient safety due to the lack of conscious sedation (particularly in those with medical comorbidities), comparable tolerability, comparable patient preference, and lower costs due to decreased direct medical costs (lack of sedation, being performed in the office) and indirect costs (lack of loss of work for the patient and the caregiver). uTNE has been shown to incite less sympathetic nervous system activity and stress as evidenced by less deleterious cardiovascular effects. It is also associated with more favorable oxygen saturation during the procedure with no intravenous access being needed. Transnasal endoscopy may also reduce risks for aspiration given less salivary stimulation and is more favorable in those with dental problems, where placement of a mouthpiece may be challenging. Finally it may also be safely performed by non-physicians after adequate training.

LIMITATIONS OF uTNE

Limitations include issues surrounding nasal intubation (failure occurs in ~2–6% of subjects due to narrow nasal passages), nasal pain and epistaxis (1–5% and usually self-limited), potential limited functionality of the endoscope (limited tip deflection, limited suction, and air insufflation), and the need for some additional provider training. A recent meta-analysis has shown that there is no significant difference in intubation rates between uTNE endoscopes <5.9 mm in diameter and conventional endoscopes in addition to excellent tolerability and acceptability. Biopsies taken with a pediatric forceps are smaller, but have been shown in comparative trials to provide adequate diagnostic information.

COST CONSIDERATIONS

Given the lack of need for sedation, uTNE can be performed at lower costs in the office, eliminating the need for intravenous access and post-procedural monitoring. Initial equipment costs include the cost of the endoscope (for conventional transnasal endoscopes that will connect with the regular light sources for transoral endoscopes) and a portable video system including the light source and display system for the esophagoscope with Endosheath technology. Reimbursement will involve the use of specific CPT codes for uTNE (43197 for uTNE without biopsy and 43198 for uTNE with biopsy) along with facility codes (specific for the hospital outpatient or ambulatory surgical center setting, if performed outside the office).

CONCLUSIONS

While conventional sedated endoscopy remains the most common form of diagnostic upper endoscopy, the utilization of uTNE will hopefully grow due to several advantages listed above. uTNE can provide similar diagnostic information for the clinician at lower costs, in a shorter time and in a safe manner without the need for sedation in the office. These advantages have the potential to make uTNE a valuable tool in the diagnostic armamentarium of the office-based gastroenterologist.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Partially funded by NIH grant (RC4DK090413).

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: Prasad G. Iyer, MD, MSc, FACG.

Specific author contributions: Prasad G. Iyer and Christopher H. Blevins drafted the manuscript and approved the final submitted draft.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Potential competing interests: None.