Abstract

Objective

Development of proteinuria in lupus nephritis (LN) is associated with podocyte dysfunction. The NLRP3 inflammasome has been implicated in the pathogenesis of LN. This study investigates whether NLRP3 inflammasome activation is involved in the development of podocyte injury in LN.

Methods

A fluorescence-labeled caspase-1 inhibitor probe was used to detect the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in podocytes in lupus-prone NZM2328 mice and in renal biopsies from LN patients. MCC950, a selective inhibitor of NLRP3, was used to treat NZM2328 mice. Proteinuria, ultrastructure of podocytes and renal pathology were evaluated. In vitro, sera from diseased NZM2328 mice were used to stimulate a podocyte cell line and cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis.

Results

NLRP3 inflammasomes were activated in podocytes of lupus-prone mice and LN patients. Inhibition of NLRP3 with MCC950 ameliorated proteinuria, renal histological lesions and podocyte foot process effacement in lupus-prone mice. In vitro, sera from NZM2328 diseased mice activated NLRP3 inflammasomes in the podocyte cell line through reactive oxygen species (ROS) production.

Conclusion

NLRP3 inflammasomes were activated in podocytes of both LN patients and in lupus-prone mice. Activation of NLRP3 is involved in the pathogenesis of podocyte injuries and the development of proteinuria in LN.

Keywords: lupus nephritis, podocytes, NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-1β

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototypic autoimmune disease. It occurs in women of childbearing age and often involves multiple organs. Lupus nephritis (LN) is one of major manifestations of SLE. Although existing treatments improved LN prognosis, only 70–80% of patients responded well [1]. There are still 10%–15% LN patients progressing to end-stage renal disease within 10 years [2]. In order to identify novel and effective therapeutic approaches, a better understanding of the pathogenic mechanism of LN is needed.

Podocytes are the major component of the glomerular filtration apparatus and are important for the maintenance of renal function. Proteinuria is one of the major features of LN and the development of proteinuria is associated with podocyte dysfunction. Indeed, podocyte injuries are present in most LN [3]. Possible mechanisms include genetic factors, inflammation, toxic injury and metabolic disturbance [4]. Although deposition of immune complexes and/or complement activation contributes to podocyte injury through the initiation of glomeruli inflammation in LN, podocytes have rarely been considered a major player in these processes. Recently, the results of a study on diabetic nephropathy demonstrating the importance of NLRP3-inflammasome activation in non-myeloid-derived cells suggest that podocytes are an active participant in making inflammatory cytokine IL-1β resulting in further recruitment of inflammatory cells [5].

The NLRP3 inflammasome is an important member of the innate immune system. Many extracellular and endogenous dangerous signals can induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation and assembly [6]. After activation, the LRR (leucine-rich repeat) domain of NLRP3 binds to the ligand, causing oligomerization of NLRP3, recruiting downstream adapter proteins ASC and pro-caspase-1 to form NLRP3 inflammasome, which subsequently self-catalyze pro-caspase-1 to become caspase-1, generating the active p10 and p20 fragments. Active caspase-1 can cleave inactive pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature forms, IL-1β and IL-18, and initiate inflammation [7].

The NLRP3 inflammasome has been implicated in the pathogenesis of LN. We have shown that inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation or blockage of its upstream P2X7 receptor reduced proteinuria in lupus prone mice [8, 9]. However, it is not clear whether NLRP3 inflammasome activation is involved in podocytes injury in LN. In this study, we examined the role of NLRP3 activation in podocytes during LN induction.

Materials and Methods

Animals

NZM2328, a new NZM strain produced by extended backcrosses of NZB/WF1 to NZW mice [10], was provided by the University of Virginia animal care facility and maintained in the specific pathogen-free colony at the Experimental Animal Center at Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University and all experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Animals. Only female mice were used in this investigation.

Single cell suspension of glomeruli for flow cytometry (FACS)

Isolation of glomeruli and single cell suspension preparations were performed as previously described by Takemoto et al [11] and modified by Sung et al [12]. Glomerular single cell suspensions were stained for glomerular resident cells using anti-mouse CD26-PE (Biolegend), Nephrin-Alexa Fluor 647 (Bioss), CD105-PE-Cy7 (Ebioscience), CD31-PerCP-Cy5.5 (Biolegend), CD45-APC-efluor 780 (Ebioscience), and FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 Assay Kit (Immunochemistry Technology). All FACS analyses were done on a Gallios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter). This procedure was described in detail by Sung et al [12].

Generation of a NZM2328 podocyte cell line and its response to NZM2328 mouse sera stimulation

An immortalized podocyte cell line was generated by transfecting isolated podocytes from a NZM2328 mouse with severe proteinuria using the retrovirus containing the vector plpcx-SVtsa58 that has the temperature sensitive simian virus 40 (tsSV40) large T antigens. Plpcx-SVtsa58, has a puromycin resistant gene as selection marker and it is similar to pZiptsa58 [13, 14]. The cell line, plpcxtSVtsa58/TeFlyMo clone 24 was kindly provided by Dr. P Jat, Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London, United Kingdom. The supernatant of this clone has the desired packaged viral particles for transforming epithelial cells. Briefly podocytes isolated from a NZM2328 female mouse with severe proteinuria were incubated with the supernatant from plpcxtSVtsa58/TeFlyMo clone 24. The cells were cultured at 33°C, 5% CO2, RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco), 100U/ml penicillin, 100mg/ml streptomycin on plates coated with rat tail collagen type I (Sigma Aldrich). The cells were allowed to grow to confluence and digested with trypsin and plated at a density of 1×104. After the cells were grown to confluence, they were processed and frozen. Some of the cells were cloned by limiting cell dilution. One of the clones that was positive for nephrin was used in this study.

For maintenance of the podocyte cell line, undifferentiated podocytes are grown under the permissive condition at 33°C, 5% CO2, RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco), 100U/ml penicillin, 100mg/ml streptomycin on plates coated with rat tail collagen type I (Sigma Aldrich). For differentiation, podocytes are cultured under the non-permissive condition at 37°C, 5% CO2, RPMI1640 with 10% FCS, 100U/ml penicillin, 100mg/ml streptomycin for 14 days.

Well-differentiated podocytes from the cell line were cultured in 6 cm culture dishes and stimulated by different stimuli (PBS, sera from 12-week-old NZM2328 mice without proteinuria and anti-dsDNA Ab, sera from 36-week-old NZM2328 mice with 3+ proteinuria and anti-dsDNA Ab and sera from 36-week-old NZM2328 mice without IgG which was depleted by Protein A+G Agarose (Beyotime). For NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition experiments, well-differentiated podocytes were cultured and primed with 1 µM selective NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 (Selleck) or 100 µM Mito TEMPO (Sigma Aldrich) for 1 hour in the presence or absence of diseased mouse sera for 12 hours. After this incubation, cells were subjected to flow cytometry and Western blot analyses for NLRP3 inflammasome activation, mitochondrial membrane potential and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) analysis.

In vivo MCC950 treatment

MCC950 was used and diluted at 1 mg/ml in vehicle (saline) solution. 20-week-old NZM2328 mice were randomized into 2 groups, vehicle group and MCC950 group (N=8 per group). Mice were treated with either MCC950 (10mg/kg) or an equal volume of vehicle every 2 days intraperitoneally at the age of 20 weeks to 26 weeks. Urines were collected every week. At the end of treatment, mice were anesthetized and kidneys were analyzed.

Another 2 groups of mice (N=8 per group) were treated as above for two weeks. After treatment, single cell suspensions of mouse kidneys were prepared and stained for flow cytometry analysis.

Mouse histology, immunofluorescence and transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Mice were perfused through their hearts under anesthesia with 40 ml cold PBS. For histology, kidneys were fixed in 10% neutral formalin and embedded in paraffin for sectioning (2µm), followed by Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining. Histopathologic evaluation was performed as previously described [8] by two observers blind to the protocol. Glomerular lesions were graded on a scale of 0–3.

For confocal microscopy, frozen kidneys were fixed in acetone. Cryostat sections (4µm) were washed 3 times with PBS and blocked for 30 min with 1% BSA in PBS. After blocking, sections were incubated with Alexa Flour A555-conjugated polyclonal anti-mouse synaptopodin Ab (Santa Cruz) and FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 assay kit (Immunochemistry Technologies) to detect caspase-1 activation in glomerular podocytes. After washings, the cells were mounted in Vectorlabs mounting media with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). It should be noted that the polyclonal anti-mouse synaptopodin Ab also reacts with human synaptopodin. In this study, this Ab from Santa Cruz Biological is used for both human and mouse tissues. A Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope was used.

For TEM, kidney tissue was fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde (wt/vol) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH7.4. The fixed tissue was processed for EM and examined with a Tecnai G2 Spirt Twin electron microscope.

Analysis of proteinuria

Mouse urine samples were tested with proteinuria analysis strips (Albustix). Six distinct colors indicate negative, trace, 30, 100, 300, and ≥2000mg/dl protein. Urine protein ≥300 mg/dl was designated as severe proteinuria.

Measurement of renal IL-1β

IL-1β in the renal protein extract was measured by IL-1β ELISA kit (Ebioscience) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blot analysis

Kidney tissues and cells from the NZM2328 podocyte cell line were processed for Western blot analysis as described previously by Zhao et al [8]. Proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. After blockade with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris buffered saline-0.1% Tween 20 (TBST), membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies (Abs): mouse anti-P2X7R (Abcam), mouse anti-NLRP3 (AdipoGen), rabbit anti-caspase-1 p20 (AdipoGen) and rabbit anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology) Abs. After washing 3 times with TBST, blots were incubated with their corresponding secondary antibodies. The signals on the membranes were detected via the chemiluminescence analysis kit (Thermo).

Human kidney immunofluorescence and urinary cell smears

Kidney biopsies were obtained from LN (class IV and class V) patients for diagnostic purposes. Renal tissue dissected adjacent to a renal tumor was obtained from a patient undergoing nephrectomy for a therapeutic reason and was considered to be “normal”. Acetone-fixed kidney cryostat sections (4µm) were washed 3 times with PBS and blocked for 30 min with 1% BSA in PBS. For the staining of human kidney sections, Alexa Flour A647-conjugated anti-synaptopodin Ab (Santa Cruz), FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 Assay kit and Alexa Flour A555 conjugated mouse mAb against human IL-1β (R&D Systems) were used. Fresh morning urine samples (100 ml) were collected from LN patients with heavy proteinuria and healthy volunteer donors and subjected to centrifugation for 10 minutes at 1500rpm. The pellets were washed with PBS 3 times and suspended in a small volume of DMEM culture medium (Life Technologies). The cells were spun onto slides by a cytospin and fixed with acetone. The slides were stained with Alexa Flour A555-conjugated anti-synaptopodin Ab (Santa Cruz) and FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 Assay kit or Alexa Flour A488 conjugated mouse mAb against human IL-1β (R&D Systems). A Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope was used.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0. The data were expressed as means ± SD. The differences were assessed by t test or one way ANOVA. Chi-square analysis was performed to compare the incidence of severe proteinuria between groups. Two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Informed Consents

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before study entry, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University.

Results

Activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in podocytes of diseased NZM2328 mice

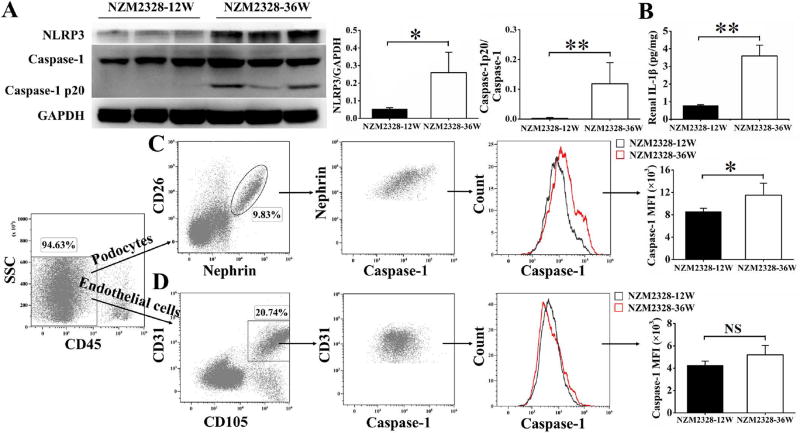

The onset of severe proteinuria is observed in some NZM2328 female mice at 16 weeks of age. By 30 weeks of age, the cumulative incidence of severe proteinuria is about 70% [10]. To assess whether NLRP3 inflammasomes were activated in mice with severe proteinuria, 36-week-old NZM2328 mice (proteinuria 3+) were examined. The diseased mice had circulating anti-dsDNA antibodies. 12-week-old NZM2328 mice (proteinuria negative without anti-dsDNA antibodies) were used as controls. Enhanced expressions of NLRP3 and activated caspase-1 that was detected as caspase-1 p20, were observed in the kidneys of 36-week-old NZM2328 mice but not in 12-week-old NZM2328 mice (Figure 1A). Renal IL-1β levels of 36-week-old NZM2328 mice were significantly higher than those of 12-week-old NZM2328 mice (Figure 1B). Glomeruli were isolated and single cell suspensions were prepared from 36-week-old and 12-week-old NZM2328 mice. A fluorescence-labeled inhibitor probe (FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 Assay Kit), which binds to intracellular active caspase-1 specifically, was used to measure levels of active caspase-1 in renal cells. The medium fluorescence intensities (MFI) of active caspase-1 in nephrin positive podocytes of 36-week-old NZM2328 mice were significantly higher than that of 12-week-old NZM2328 mice (Figure 1C). There was no significant difference in MFI of active caspase-1 in CD31 positive endothelial cells between the two groups (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in podocytes of diseased NZM2328 mice.

A, Representative Western blot bands (left) and relative expression levels in each group (right) showed the expression of NLRP3 and caspase-1 p20, normalized to the values of GAPDH and caspase-1 in the kidneys of 36-week-old NZM2328 mice versus 12-week-old NZM2328 mice. B, Levels of IL-1β in renal extracts of NZM2328 mice. Glomeruli were isolated from NZM2328 mice and single cell suspensions were prepared. Flow cytometry analysis was used to assess the active caspase-1 levels in podocytes (C) and endothelial cells (D). Results are mean ± SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, NS = no significance, n=3 per group.

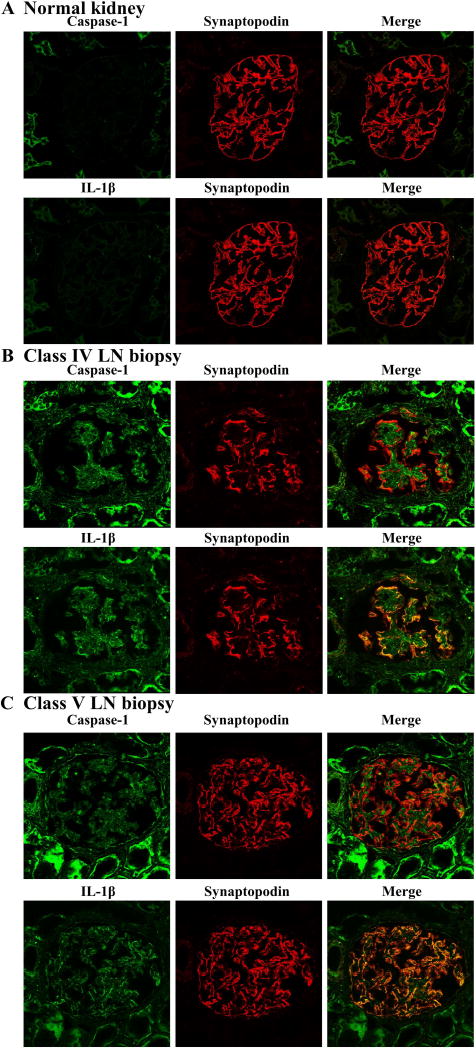

Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in podocytes of human LN biopsies

We then examined whether NLRP3 inflammasome activation is also present in podocytes of LN patients. By using a fluorescence-labeled Ab to synaptopodin to mark podocytes and FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 Assay kit to label active caspase-1 enzyme, colocalization of active caspase-1 and synaptopodin in the kidney biopsies from LN patients were visualized by confocal microscopy. Nine patients with class IV LN and four patients with class V LN were studied. In all cases, activation of NLRP3 inflammasome was detected in podocytes. Representative cases of class IV and class V LN are presented in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2A, activation of NLRP3 inflammasome was not detected in the podocytes of normal kidneys. There was no staining for IL-1β. However there was detection of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and expression of IL-1β in the tubular cells. In contrast, both activation of NLRP3 inflammasome and expression of IL-1β were readily detected in both class IV and class V LN (Figures 2B and 2C. It is of note that the intensity of staining for caspase-1 and IL-1β was similar in class IV and class V specimens. The staining of tubular cells for both caspase-1 and IL-1β was stronger in LN in comparison to that in normal kidneys.

Figure 2. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in podocytes of human LN biopsies.

Human kidney biopsies were collected and prepared for immunofluorescence staining. Anti- synaptopodin Ab (red), FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 assay kit (green) and mAb anti-human IL-1β (green) were used to detect expression of active caspase-1 and IL-1β in podocytes in the human kidneys. (A) Normal kidney isolated from non-disease area of nephrectomy specimen from a patient with renal cell cancer. (B) Class IV LN biopsy and (C) Class V LN biopsy. Original magnification ×400.

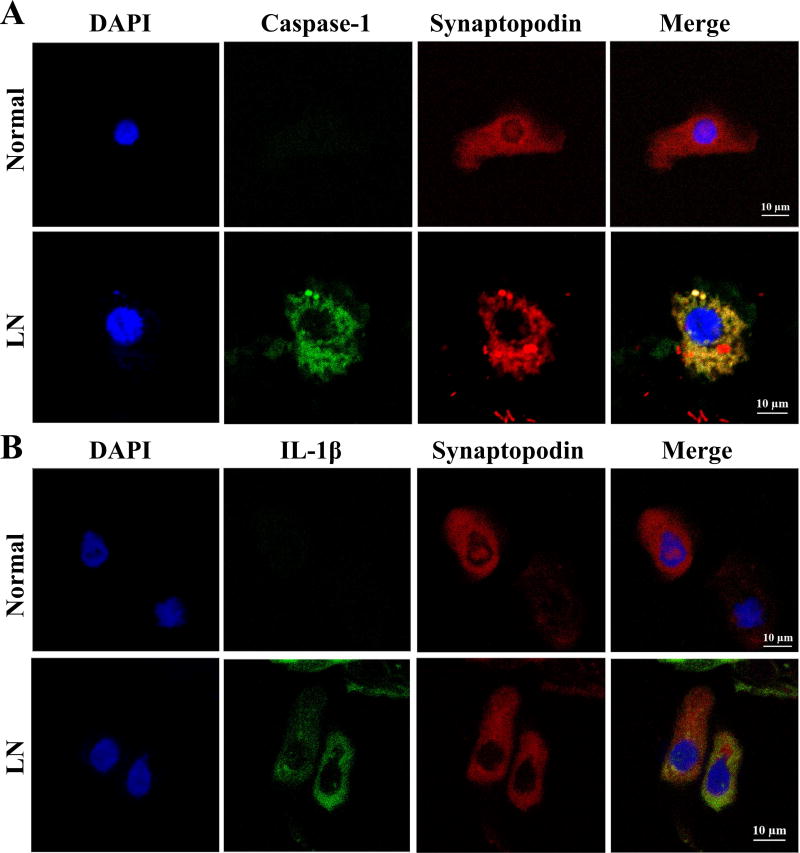

Activated NLRP3 inflammasome in urinary podocytes

To further confirm the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the podocytes in LN, urinary podocytes from active LN patients and normal individuals were examined. As shown in Figure 3, podocytes identified in the urine by synaptopodin staining were seen in both normal volunteers and patients with LN. Colocalization of synaptopodin and active caspase-1 was observed only in the urinary podocytes from active LN patients (Figure 3A). There is also colocalization of synaptopodin with IL-1β in these urine cells (Figure 3B). Podocytes from the urine of healthy volunteers did not stain for active caspase-1 or IL-1β. These findings were observed in five patients with class IV LN and in three healthy controls.

Figure 3. Activated NLRP3 inflammasome in urine podocytes.

Fresh urine was collected and cells were spun onto a slide by a Cytospin. They were fixed and stained with anti- synaptopodin Ab (red), FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 assay kit (green) and mAb anti-human IL-1β (green) to detect expression of active caspase-1 and IL-1β in urine podocytes. DAPI (blue) was used to stain nuclei. (A) Expression of caspase 1 in the urinary podoycyte in a patient with LN but not in that of a normal individual. (B) Detection of IL-1β in the urine podocytes in a patient with LN but not from a normal control. Original magnification ×630.

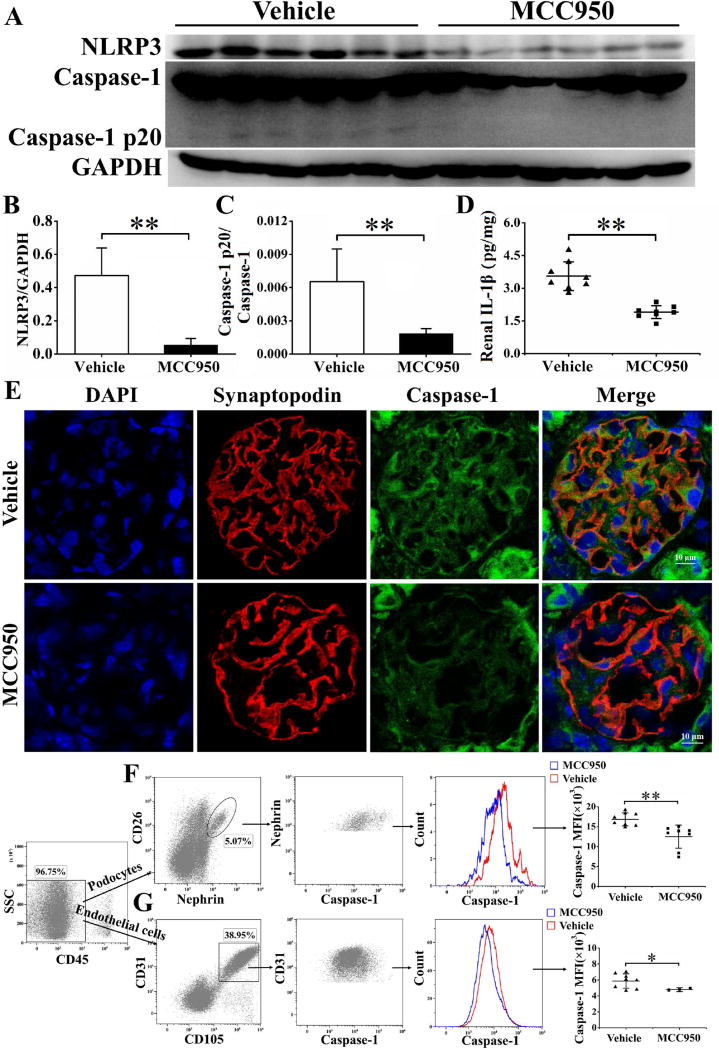

MCC950 treatment reduced caspase-1 activation in podocytes of NZM2328 mice

MCC950, a selective NLRP3 inhibitor, was used to treat NZM2328 mice. Following 6 weeks of treatment, the expression of NLRP3 and caspase-1 p20, the active form of caspase-1, was significantly inhibited compared to the vehicle group (Figure 4A, 4B and 4C). MCC950 treatment significantly reduced the production of IL-1β in the kidneys (Figure 4D). Fluorescence-conjugated anti-synaptopodin Ab and FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 assay kit were used to detect active caspase-1 expression in glomerular podocytes. As shown in figure 4E, the podocytes from mice of the group treated with the vehicle had brighter green staining than the MCC950 treated group (Figure 4E) suggesting that activation of caspase-1 was inhibited by MCC950. The medium fluorescence intensities (MFI) of active caspase-1 in both podocytes and endothelial cells were significantly reduced following MCC950 treatment (Figure 4F and 4G). It appears that MCC950 did not block significantly the activation of caspase-1 in the tubular cells.

Figure 4. MCC950 inhibited activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in NZM2328 mice and reduced IL-1β production.

Following 6 weeks’ treatment of MCC950, mouse kidneys were collected for the following analysis. A–C, the kidneys were subjected to Western blot (representative bands shown) for expression of caspase 1 and its active form caspase-1 p20. D, levels of IL-1β in kidney extract determined by ELISA. E, anti-synaptopodin Ab (red) and FAM-FLICA Caspase-1 assay kit were used to detect caspase-1 expression (green) in glomerular podocytes, cell nuclei were marked by DAPI (blue). Original magnification ×400. After 2 weeks’ treatment, flow cytometry analysis was used to assess the active caspase-1 levels in podocytes (F) and endothelial cells (G). Results are mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, n=8 per group.

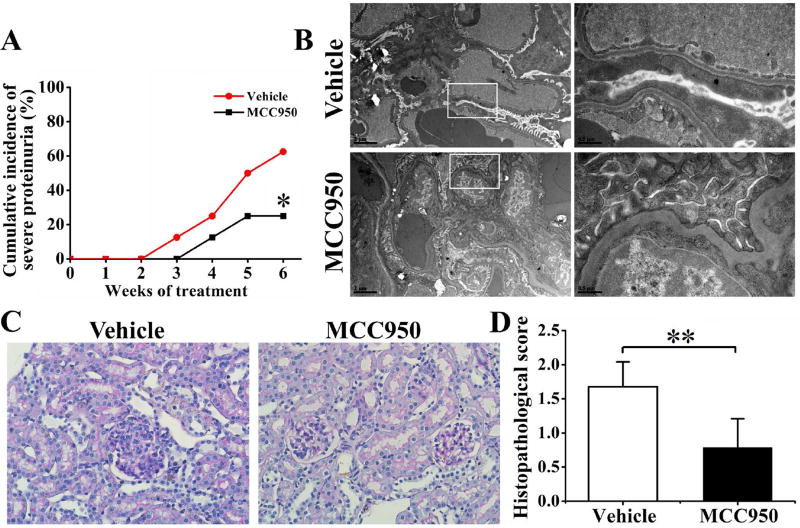

MCC950 treatment reduced proteinuria and renal lesions in NZM2328 mice

We further assessed the effects of inhibition of NLRP3 activation in podocytes during the onset of proteinuria. As shown in Figure 5A, vehicle-treated NZM2328 mice began to present severe proteinuria (≥3+) from 23-weeks of age (week 3 after the start of treatment with vehicle). Compared with the vehicle-treated group, the proportion of severe proteinuria was significantly less in the MCC950-treated group. Transmission electron microscopy showed that MCC950 treatment significantly attenuated foot process effacement (Figure 5B). The glomerular histology was also significantly improved in the treated group with lower histopathological scores (Figure 5C and 5D).

Figure 5. MCC950 treatment reduced renal lesions and proteinuria in NZM2328 mice.

A, Severity of proteinuria (recorded weekly). B, Transmission electron microscopy was used to assess podocytes foot process. Original magnification ×5800 (left) and ×26500 (right). C, Renal sections were stained with PAS to assess features of glomerulonephritis. Original magnification ×400. D, Histopathological scores were recorded. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, n=8 per group.

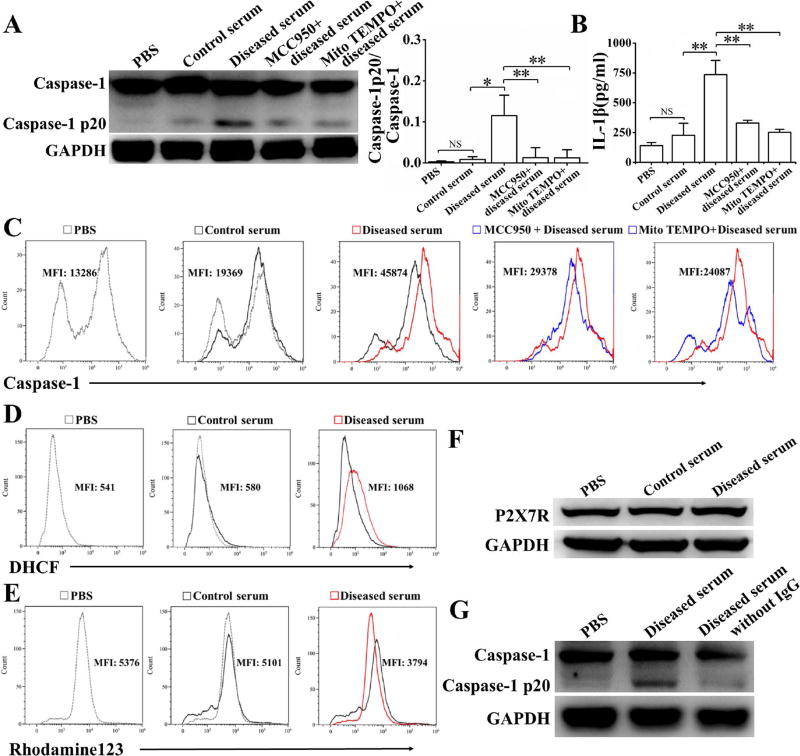

Serum from diseased NZM2328 mice activated NLRP3 inflammasome in podocytes

To ascertain the role of autoantibodies on NLRP3 activation in podocytes, cells of the NZM2328 podocyte cell line were stimulated with sera from diseased NZM2328 mice. Compared to pooled control sera and PBS, sera from mice with severe proteinuria and anti-dsDNA antibodies were shown to activate NLRP3 inflammasomes in the NZM2328 podocyte line as measured by Western blot (Figure 6A) and by flow cytometry (Figure 6C), and increased the production of IL-1β (Figure 6B). The production of ROS measured by DHCF (Figure 6D) was significantly increased and mitochondrial membrane potentials measured by Rhodamine 123 (Figure 6E) were significantly decreased in cells treated with pooled sera from mice with severe proteinuria. However, the expression of P2X7R was not elevated after stimulation with pooled sera from diseased mice (Figure 6F). Furthermore, MCC950, which specifically inhibits NLPR3 inflammasome activation [15], and Mito TEMPO, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, significantly inhibited the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome (Figure 6A and 6C) and the production of IL-1β (Figure 6B). Additional experiments were carried out using IgG depleted serum samples isolated from diseased mice. IgG depleted serum samples failed to activate caspase-1, suggesting that the active component in the diseased mouse sera were IgG (Figure 6G).

Figure 6. Serum from diseased NZM2328 mice activate NLRP3 inflammasome in podocytes.

The NZM2328 podocyte cell line was stimulated with a control serum or a serum from diseased NZM2328 mice or serum from diseased NZM2328 mice depleted of IgG, with or without MCC950 or Mito TEMPO for 24 hours. A, Representative Western blot (left) and relative expression levels (right) in each group showed the expression of caspase-1 p20, normalized to the values of caspase-1. B, Levels of IL-1β in supernatant following different stimulation. Flow cytometry analysis was used to assess active caspase-1 levels (C), production of ROS (D) and mitochondrial membrane potential (E). F, Expression of P2X7R detected by Western blot. G, Caspase-1 p20 expression analysis followed stimulation with diseased serum or diseased serum depleted of IgG. Results were mean ± SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, NS = no significance.

Discussion

Podocytes are highly specialized cells located outside the basement membrane of glomeruli. They express markers including synaptopodin, Wilms tumor protein 1 (WT1), glomerular epithelial protein 1 (GLEPP1) and nephrin. These molecules have important roles for maintaining filtration barrier integrity [16]. With the identification of podocyte specific markers, it is now feasible to study podocyte response to injuries in various disease states. In this study, we have utilized biomarkers to isolate intrinsic renal cells from a mouse model of LN. We have documented that NLRP3 is activated in podocytes in LN responding to immunological injury. However, the mechanisms by which these processes relate to podocyte injury remain to be elucidated. Nevertheless, our observations document that podocytes play an active role in the disease process in LN, adding credence to our long-held hypothesis that end organ resistance to damage under genetic control plays an important role in the pathogenesis of LN [17, 18]. Our observations provide the impetus to focus more on investigating intraglomerular cellular interactions in the pathogenesis of LN. In this regard, it would be of interest to determine whether similar observations would be made in NZM2328.c1R27 (R27) female mice [19] that are resistant to the progression of proliferative immune-complex mediated nephritis to severe proteinuria and end stage renal disease. This is of particular relevance in view of our recent observation that the unique intraglomerular macrophages (CD11b+F4/80−I-A−) are seen in NZM2328 kidneys with chronic glomerulonephritis and severe proteinuria but not in R27 [12].

The exact mechanism of podocyte injury is not yet fully elucidated. Inflammation has been implicated in the podocyte dysfunction in renal diseases with proteinuria [4]. In this study, by using a probe of active caspase-1, we showed the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in podocytes from human LN biopsies and in urinary podocytes. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome was also confirmed by isolated primary podocytes from lupus-prone NZM2328 mice with severe proteinuria. In contrast, no activation of NLRP3 was found in podocytes from NZM2328 mice without proteinuria. Our results may favor the interpretation that the activation of inflammasomes is associated with podocyte injuries in LN. More definitive evidence may be forthcoming with the generation of a conditional knockout of NLPR3 in podocytes in NZM2328.

Recently much interest has focused on the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in kidney disease and autoimmunity [20–22]. Using a similar approach as that in the present study, Xiong et al [20] demonstrated the activation of caspase-1 in podocytes in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis and membranous nephropathy. To a lesser degree, some podocytes in IgA nephropathy were shown to express caspase-1. The latter findings collaborates the recent observation that NLRP3 localized to the tubular epithelium in human kidneys correlates with outcome in IgA nephropathy [23]. Activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in tubular cells has been considered a mechanism for kidney damage in acute and chronic kidney injuries caused by ischemia reperfusion injury, drugs, rhabdomyolysis, glucose, crystals and unilateral nephrectomy [21, 22, 24]. Little information is available regarding the role of podocyte responses to these insults on the kidney. In the present study we did notice that caspase-1 activation is seen in the tubular cells of normal kidneys and this activation is enhanced in the tubular cells in biopsies of class IV and class V LN kidneys. It remains to be determined whether this activation contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of LN or is the byproduct of proteinuria [25].

The role of NLRP3 in adaptive immunity should be considered. Hutton et al [21] considered the major effect of NLRP3 inflammasome on the adaptive immunity is through its effect on the modulation of the T helper cell subsets, skewing development in favor of Th17 and Th1 cells. Since few T cells are within the glomeruli, the effects of intraglomerular NLRP3 inflammasome activation may not have much effect on the overall intrarenal T cell subsets. On the other hand, because most infiltrating renal T cells are located in the peri-glomerular region, the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in the tubular and interstitial cells may have paramount effects on T cells. It should be noted that in the MCC950 treated mice, the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome are not significantly downregulated in the tubular and interstitial cells. This observation suggests that activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes may not be affected in the interstitium by our treatment protocol. Thus the Th1 and Th17 subsets in the kidneys of MCC950 treated and vehicle treated mice may be similar. The effect of NLRP3 inflammasome activation on the adaptive immunity can be ascertained by assaying Th1 and Th17 subsets in the kidneys treated with MCC950.

Our study documents that IL-1β is expressed by podocytes as a result of NLRP3 activation. IL-lβ is a potent proinflammatory cytokine and has been shown to repress nephrin promoter activity and the transcription of nephrin in podocytes [26]. The downregulation of nephrin expression may interfere with the integrity of podocytes as a filtration barrier, providing a mechanism for podocyte injury and renal impairment. In the present study, podocytes were shown to express IL-1β in both LN biopsies and in urinary podocytes. This observation collaborates the previous observation that podocytes are the major source of IL-lβ in human and rat glomerulonephritis [27, 28]. Together with our published results, our present observation that treatment of NZM2328 mice with a specific NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 suppresses the activation of NLRP3 activation in podocytes, resulting in reduced podocyte foot process effacement and decreased proteinuria would again support the thesis that IL-1β would be a target for the treatment of lupus nephritis. This is particularly relevant in repositioning approved drugs for the treatment of LN in view of the approval of IL-1ra for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

There are conflicting results regarding the effectiveness of IL-1ra in the treatment of glomerulonephritis. It is effective in preventing the development of anti-GBM nephritis and in the treatment of established anti-GBM nephritis [29–31]. However, it has been reported that it is not effective in reversing established nephritis in MRL/lpr [32]. It was partially effective in treating the nephritis in NZB/W F1 [33]. Our previous published data [8, 9] and the results of the present investigation indicate that targeting the NLRP3-IL-1β pathway is beneficial in treating LN in mouse models. In view of the recent observation that inhibition of IL-1 receptor signaling prevented, or even reversed, diabetic nephropathy in mice [5], further investigation is needed to determine whether targeting the NLRP3-IL-1β signaling pathway would be beneficial in the treatment of LN.

NLRP3 inflammasomes can be activated by a variety of stimuli, among them mitochondrial injury is a common and most important intracellular stimulus [34]. When mitochondria are injured or stressed, mitochondrial membrane potential (∆ψm) decreases resulting in the release of harmful molecules, such as ROS. These molecules then activate NLRP3 inflammasomes and up-regulate IL-1β and IL-18, thus exacerbating inflammation [35]. In our study, sera from diseased lupus-prone mice activated NLRP3 inflammasomes and increased the production of IL-1β in podocytes in the NZM2328 cell line, but did not interfere with the expression of K+ channel P2X7R, an upstream molecule of the NLRP3 pathway. In addition, mitochondrial membrane potential was shown to decrease with significant increased production of ROS. The activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes was inhibited by mitochondrial ROS inhibitors. These findings indicate that sera from diseased mice activated NLRP3 inflammasomes though ROS generated by injured mitochondria. Thus, far we have documented that the active component in the sera of diseased mice is IgG. However, how these IgG molecules cause mitochondrial damage remains to be determined. One plausible mechanism is that these IgG molecules enter podocytes via FcRn. This mechanism is supported by the recent observation that IgG from lupus patients entered podocytes via the FcRn receptor and upregulated CaMKIV followed by increased expression of genes related to podocyte damage and T cell activation [36]. It should be clear that other mechanisms are plausible.

Podocytes appear in the urine of healthy subjects and increased urinary excretion of podocytes (podocyturia) is found in proteinuric states [37]. Urinary podocytes have been used to assess disease activity in LN [38]. In this study, we identified urine podocytes with positive staining for activated caspase-1 and IL-1β. Whether such podocytes are associated with disease activity in the kidneys of SLE needs further investigation.

In conclusion, our studies show that NLRP3 inflammasomes are activated in podocytes of both LN patients and lupus-prone mice. Activation of NLRP3 is involved in the pathogenesis of podocyte injuries and the development of proteinuria in LN. In addition, our study supports the thesis that targeting the NLRP3-IL-1 for the treatment of LN may be of promise.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471598, 81671593) and Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (2014A030313096), Guangzhou Science and Technology Planning Program (201605122113460); SM Fu was supported in part by NIH grant (NIH R01 AR-047988) and a grant from the Alliance for Lupus Research (TIL332635).

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Yang and SM. Fu had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. R. Fu, Guo, S. Wang, Yang, SM. Fu.

Acquisition of data. R. Fu, Guo, S. Wang, Huang, Hu, Jin, Chen, Xu, Zhou, Zhao, Sung, H Wang, Gaskin, Yang, SM Fu.

Analysis and interpretation of data. R. Fu, Guo, S. Wang, Huang, Hu, Jin, Chen, Xu, Zhou, Zhao, Sung, H Wang, Gaskin, Yang, SM Fu.

Financial Disclosure: None have conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gregersen JW, Jayne DR. B-cell depletion in the treatment of lupus nephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:505–14. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faurschou M, Dreyer L, Kamper AL, Starklint H, Jacobsen S. Long-term mortality and renal outcome in a cohort of 100 patients with lupus nephritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:873–80. doi: 10.1002/acr.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Yu F, Song D, Wang SX, Zhao MH. Podocyte involvement in lupus nephritis based on the 2003 ISN/RPS system: a large cohort study from a single centre. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53:1235–44. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cellesi F, Li M, Rastaldi MP. Podocyte injury and repair mechanisms. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24:239–44. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shahzad K, Bock F, Dong W, Wang H, Kopf S, Kohli S, et al. Nlrp3-inflammasome activation in non-myeloid-derived cells aggravates diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2015;87:74–84. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes (review) Cell. 2014;157:1013–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang CA, Chiang BL. Inflammasomes and human autoimmunity: A comprehensive review (review) J Autoimmun. 2015;61:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao J, Wang H, Dai C, Zhang H, Huang Y, Wang S, et al. P2X7 blockade attenuates murine lupus nephritis by inhibiting activation of the NLRP3/ASC/caspase 1 pathway. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:3176–85. doi: 10.1002/art.38174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J, Wang H, Huang Y, Zhang H, Wang S, Gaskin F, et al. Lupus nephritis: glycogen synthase kinase 3beta promotion of renal damage through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in lupus-prone mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2015;67:1036–44. doi: 10.1002/art.38993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waters ST, Fu SM, Gaskin F, Deshmukh US, Sung SS, Kannapell CC, et al. NZM2328: a new mouse model of systemic lupus erythematosus with unique genetic susceptibility loci. Clin Immunol. 2001;100:372–83. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takemoto M, Asker N, Gerhardt H, Lundkvist A, Johansson BR, Saito Y, et al. A new method for large scale isolation of kidney glomeruli from mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:799–805. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64239-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sung SJ, Ge Y, Dai C, Wang H, Fu SM, Sharma R, et al. Dependence of Glomerulonephritis Induction on Novel Intraglomerular Alternatively Activated Bone marrow-Derived Macrophages and Mac-1 and PD-L1 in Lupus-Prone NZM2328 Mice. J Immunol. 2017;198:2589–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jat PS, Sharp PA. Cell lines established by a temperature-sensitive simian virus 40 large-T-antigen gene are growth restricted at the nonpermissive temperature. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1672–81. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Hare MJ, Bond J, Clarke C, Takeuchi Y, Atherton AJ, Berry C, et al. Conditional immortalization of freshly isolated human mammary fibroblasts and endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:646–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coll RC, Robertson AA, Chae JJ, Higgins SC, Munoz-Planillo R, Inserra MC, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21:248–55. doi: 10.1038/nm.3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rezende GM, Viana VS, Malheiros DM, Borba EF, Silva NA, Silva C, et al. Podocyte injury in pure membranous and proliferative lupus nephritis: distinct underlying mechanisms of proteinuria? Lupus. 2014;23:255–62. doi: 10.1177/0961203313517152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waters ST, McDuffie M, Bagavant H, Deshmukh US, Gaskin F, Jiang C, et al. Breaking tolerance to double stranded DNA, nucleosome, and other nuclear antigens is not required for the pathogenesis of lupus glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:255–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai C, Deng Y, Quinlan A, Gaskin F, Tsao BP, Fu SM. Genetics of systemic lupus erythematosus: immune responses and end organ resistance to damage. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;31:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ge Y, Jiang C, Sung SS, Bagavant H, Dai C, Wang H, et al. Cgnz1 allele confers kidney resistance to damage preventing progression of immune complex-mediated acute lupus glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2387–401. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong J, Wang Y, Shao N, Gao P, Tang H, Su H, et al. The expression and significance of NLRP3 inflammasome in patients with primary glomerular diseases. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2015;40:344–54. doi: 10.1159/000368511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutton HL, Ooi JD, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR. The NLRP3 inflammasome in kidney disease and autoimmunity. Nephrology (Carlton) 2016:736–44. doi: 10.1111/nep.12785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masood H, Che R, Zhang A. Inflammasomes in the pathophysiology of kidney diseases. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2015;1:187–93. doi: 10.1159/000438843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chun J, Chung H, Wang X, Barry R, Taheri ZM, Platnich JM, et al. NLRP3 localizes to the tubular epithelium in human kidney and correlates with outcome in IgA nephropathy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24667. doi: 10.1038/srep24667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komada T, Usui F, Kawashima A, Kimura H, Karasawa T, Inoue Y, et al. Role of NLRP3 inflammasomes for rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10901. doi: 10.1038/srep10901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhuang Y, Yasinta M, Hu C, Zhao M, Ding G, Bai M, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction confers albumin-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and renal tubular injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;308:F857–66. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00203.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takano Y, Yamauchi K, Hayakawa K, Hiramatsu N, Kasai A, Okamura M, et al. Transcriptional suppression of nephrin in podocyte by macrophage: roles of inflammatory cytokines and involvement of PI3K/Akt pathway. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:421–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niemir ZI, Stein H, Dworacki G, Mundel P, Koehl N, Koch B, et al. Podocytes are the major source of IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta in human glomerulonephritides. Kidney Int. 1997;52:393–403. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tesch GH, Yang N, Yu H, Lan HY, Foti R, Chadban SJ, et al. Intrinsic renal cells are the major source of interleukin-1 beta synthesis in normal and diseased rat kidney. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:1109–15. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.6.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan HY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Zarama M, Vannice JL, Atkins RC. Suppression of experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis by the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Kidney Int. 1993;43:479–85. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang WW, Feng L, Vannice JL, Wilson CB. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist ameliorates experimental anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody-associated glomerulonephritis. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:273–79. doi: 10.1172/JCI116956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lan HY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Mu W, Vannice JL, Atkins RC. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist halts the progression of established crescentic glomerulonephritis in the rat. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1303–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiberd BA, Stadnyk AW. Established murine lupus nephritis does not respond to exogenous interleukin-1 receptor antagonist; a role for the endogenous molecule? Immunopharmacology. 1995;30:131–7. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(95)00014-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun H, Liu W, Shao J. Study of immunoregulation by interleukin-1 receptor antigonist in NZB/W F1 mice. Zhonghua yi xue za zhi. 1996;76:600–2. (Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes (review) Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nri3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sadatomi D, Nakashioya K, Mamiya S, Honda S, Kameyama Y, Yamamura Y, et al. Mitochondrial function is required for extracellular ATP-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Biochem. 2017 doi: 10.1093/jb/mvw098. https://doi.org/10.1093/jb/mvw098. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Ichinose K, Ushigusa T, Nishino A, Nakashima Y, Suzuki T, Horai Y, et al. Lupus Nephritis IgG Induction of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinase IV Expression in Podocytes and Alteration of Their Function. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:944–52. doi: 10.1002/art.39499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogelmann SU, Nelson WJ, Myers BD, Lemley KV. Urinary excretion of viable podocytes in health and renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F40–48. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00404.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakamura T, Ushiyama C, Suzuki S, Hara M, Shimada N, Sekizuka K, et al. Urinary podocytes for the assessment of disease activity in lupus nephritis. Am J Med Sci. 2000;320:112–6. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]