I. INTRODUCTION

As of January 2014, 26 states had chosen to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to cover individuals with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level.1 In these states, Medicaid agencies are facing one of the largest implementation challenges in the program’s history. We undertook a survey of high-ranking Medicaid officials in these states to assess their priorities, expectations, and programmatic decisions related to the coming expansion.

The Medicaid expansion poses major challenges in the domains of enrollment, management of health care costs, and providing adequate access to services for beneficiaries.2 Previous research has documented that millions of individuals eligible for Medicaid are currently not enrolled and remain uninsured,3 suggesting that state outreach strategies may underpin the success or failure of the ACA’s coverage expansion. With the problematic launch of the Federal Marketplace in October 2013, concerns have grown about the ability of states and the federal government to enroll eligible individuals.4

New enrollment among previously-eligible individuals (the so-called “woodwork effect” or “welcome-mat effect”) also may have major budget implications for states, since they will have to pay a larger share of costs for this group.5 More generally, with spending on Medicaid increasing significantly in recent years, cost projections and approaches to managing program costs are critical and have played a key role in states’ debates over whether to expand Medicaid in 2014.6

Lastly, recent studies have demonstrated Medicaid’s value in expanding access to needed services, with somewhat conflicting results regarding its impact on various health measures.7 At the same time, the program is faced with ongoing limitations in terms of the number of providers willing to care for Medicaid patients8 and potential disruptions in coverage over time under the ACA, as patients cycle in and out of Medicaid eligibility.9 While the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has recently put out guidance to states on potential options to mitigate the impact of such coverage churning, as well as to increase enrollment more generally,10 it remains unclear how many states are pursuing various options along these lines.

With major policy changes underway for nearly all aspects of the Medicaid program, understanding the perspectives of state leaders is critical. One recent article examined governors’ perspectives on the Medicaid expansion,11 but in this study, we targeted state Medicaid directors to focus on those officials actively supervising the details of implementation who may be closest to the everyday operational realities of the expansion. Two recent reports featuring surveys of Medicaid officials have focused on fiscal concerns and issues of integration of care.12 Our study aims to build on this body of knowledge in the context of the quickly changing political environments at the state and federal levels, while covering a more comprehensive set of policy issues. Furthermore, by focusing specifically on those experiences of officials in states expanding Medicaid for 2014, we were able to explore in more depth the specific policies states are pursuing in the areas of outreach and enrollment, cost control, and improving access to care for newly-eligible adults.

Overall, our key findings—described in Part III below—show that Medicaid officials in expanding states were optimistic about the success of enrollment efforts, with community-based assistance predicted to play a large role in ensuring high enrollment rates.13 However, state officials expressed concerns regarding costs to the state budget and remaining barriers related to newly-eligible beneficiaries’ access to care.14 Officials unanimously reported a heavy reliance on delivery system and payment reform to help control costs, with managed care also playing a key role.15 Despite implementation challenges, Medicaid officials predicted that the expansion will deliver positive effects on health, access to care, and financial protection for those newly-eligible for Medicaid coverage.16

II. METHODS

A. Study Design

We used a structured in-depth survey of Medicaid directors in states expanding Medicaid in 2014 to investigate key policy issues relating to the expansion. We contacted the current Medicaid directors in all 26 expanding states including Washington, D.C. in cooperation with co-investigators at the Center for Health Care Strategies.17 Officials were first contacted with general information about the study and were informed that participation was voluntary and confidential. After officials consented, they were sent the survey and invited to participate in a telephone call to review their responses.

We obtained responses from 23 of 26 states (a response rate of 88%) and conducted interviews between July 8, 2013 and November 5, 2013. All but two interviews were completed before the ACA’s open enrollment period began on October 1, 2013. In eighteen states (78%) we spoke with the Medicaid director, and in the remaining five (22%) we spoke with other high-ranking Medicaid officials appointed by the director to complete the survey. To protect confidentiality, we are unable to provide further details on the official titles or state of origin for each official.18

B. Survey Development

Topics selected for inclusion in the survey were based on prior research that identified major policy challenges in Medicaid,19 as well as a series of semi-structured interviews conducted from December 2012 to February 2013 with six Medicaid directors who had previous experience implementing coverage expansions.20 Survey domains included outreach efforts and predictions regarding enrollment; the role of pre-existing state programs as a basis for the Medicaid expansion; cost-control mechanisms and budget projections; potential barriers to care for new enrollees; and major implementation challenges.21 The survey was pilot-tested with two former Medicaid directors and refined based on multiple rounds of feedback.

C. Data Analysis

We analyzed survey responses using descriptive statistics of frequencies and means. Results were based on the total number of officials to each item; the denominator for each question excluded item non-responses. For several variables of interest, we conducted bivariate analyses based on policy-relevant characteristics, such as the state’s expected budgetary impact of the expansion and whether states will have state-run or federally assisted exchanges under the ACA22 (the federal exchange was recently renamed the Federal “Marketplace,” though our survey instrument referred to “Exchanges,” so we primarily use that terminology here). We tested for bivariate associations in the survey responses using chi-square tests for categorical data and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for ordinal data.

D. Limitations

Our analysis has several limitations. The first is the small sample size. While our survey attained a very high response rate (88%) in a time of tremendous time constraints on state officials, we were restricted by the number of states expanding Medicaid for 2014.23 Thus our results are primarily useful at a descriptive level, with limited power for identifying statistical significance. Second, many survey questions asked about officials’ perceptions or projections for the Medicaid expansion.24 Such responses are subjective and may not have been supported by actual data; however, they provide a useful portrait of the perceptions of state Medicaid leaders and may be prescient in identifying key challenges in the ACA expansion.

Lastly, despite the assurance of confidentiality and questions designed to be neutral, social desirability bias may have affected officials’ responses. This may have been the case particularly when considering questions that could cast their programs or states in a negative light or undermine political support for their policies. Nonetheless, the officials surveyed offered numerous examples of concerns or challenges they are facing in their program, suggesting that most officials were not providing an overly varnished view of the Medicaid expansion.

III. RESULTS

A. Enrollment in the Medicaid Expansion

Overall, predictions of enrollment were optimistic. Table 1 summarizes responses regarding the coverage impacts of the expansion.25 76% of officials estimated that between half and three-quarters of newly-eligible uninsured adults in their state will sign up for Medicaid.26 Two states predicted that 76–90% will participate, while three predicted enrollment will be under 50%.27 The vast majority of state Medicaid officials (73%) reported that they also expect “moderate” or “large” enrollment increases among individuals previously eligible for Medicaid who had not yet signed up for the program (the woodwork effect).28

The majority of states (55%) have pre-existing state-funded insurance programs for low-income adults that will be partially or fully replaced by the Medicaid expansion in 2014.29 Half of these states have small programs, comprising less than 25% of their Medicaid expansion; however, four states expect that the majority of new enrollment in Medicaid in 2014 will come from transferring individuals enrolled in pre-existing programs.30

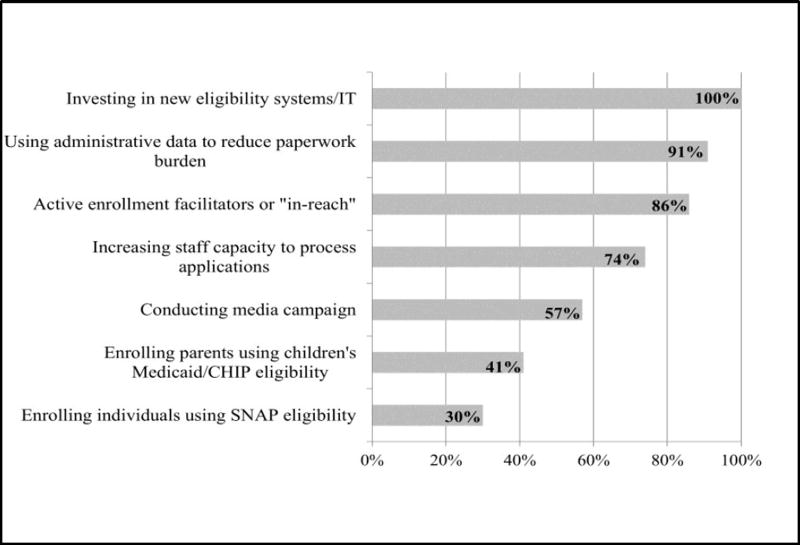

When asked what single factor will have the largest impact on whether newly-eligible individuals enroll in Medicaid in their state, 59% of officials indicated “active outreach and community-based application assistance,” while 18% answered public education efforts.31 Figure 1 presents policies that states are employing to encourage enrollment, with the implementation of new information technology (IT) systems (100%), the use of administrative data to reduce paperwork burden on applicants (91%), and the use of enrollment facilitators (86%) emerging as the most common approaches.32

Overall, officials expect most Medicaid applications to come via state-based Exchanges (23%), navigators/outreach assistance (23%), or directly to Medicaid (45%); none expected Healthcare.gov to be the primary means of Medicaid enrollment.33 Table 2 shows the expected paths of enrollment for new applicants, depending on each state’s Exchange type.34 All states with federally-facilitated or partnership Exchanges expect direct applications to the Medicaid agency to be the primary enrollment pathway.35 In contrast, states with state-based Exchanges expect that most applicants will come via their Exchange or navigator/outreach assistance.36

B. Costs of the Medicaid Expansion

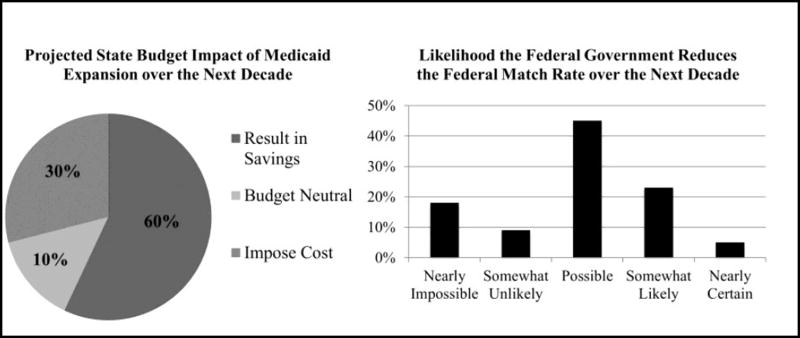

The majority of officials (57%) predicted that the Medicaid expansion will result in savings for their states’ budgets over the next decade when factoring in offsetting savings in uncompensated care and pre-existing state-funded insurance programs.37 While 14% predicted budget neutrality, a sizable minority (29%) expect increased state spending on Medicaid (Figure 2).38

We probed the reasons for these predictions based on the components of potential state costs—reduced spending on uncompensated care, the extra expenses engendered by the woodwork effect, replacement of state-financed insurance programs with Federal Medicaid dollars, and expectations about federal spending on Medicaid over the next decade. Table 3 presents these results for the full sample, and Table 4 presents them stratified by each state’s predicted overall budget impact.39

The sharpest difference underlying distinct budget expectations for the expansion was the perceived likelihood that the federal government will cut the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (the FMAP, sometimes referred to as the “match rate”) promised in the ACA due to budget pressures over the next decade.40 Overall, 73% of officials said such a cut is “possible,” “somewhat likely,” or “nearly certain.”41 Among officials predicting state costs to increase under the expansion, 83% thought that future FMAP cuts were “possible” or “likely,” with one official saying it was “nearly certain,” while only 58% among those expecting budget savings thought cuts were “possible or likely” and none thought it was “nearly certain” (p=0.02).42

Other cost-related differences in responses were suggestive, but not statistically significant. Among states expecting net savings, 67% have pre-existing programs that will substitute federal dollars for state funds in 2014, compared to only 33% among states predicting net costs from the expansion (p=0.18).43 One hundred percent of states expecting higher costs under the expansion envision at least a “moderate” woodwork effect, compared to 58% among states expecting budget savings from the expansion (p=0.17).44 Both groups expected similar reductions in state spending on uncompensated care.45

In terms of cost-containment, 95% of officials cited new payment models or new care delivery models as one of the two most promising ways to control program costs.46 The most common examples mentioned were patient-centered medical homes, accountable care organizations (ACOs), and improved coordination of services for dually eligible individuals enrolled in both Medicaid and Medicare. Fifty-five percent of officials viewed Medicaid managed care as a promising way to reduce costs.47 Officials reported that the vast majority of the newly-eligible population in their states will be enrolled in Medicaid managed care, with 11 states reporting that between 76% and 99% of new beneficiaries will be in managed care and 9 states predicting 100% in managed care.48 Zero officials identified cutting reimbursement to providers or limiting covered benefits as key cost-control options.49

C. Access to Care

Table 5 presents responses regarding the expected impact of the expansion on access to care for low-income Americans.50 Officials were nearly unanimous that expanded Medicaid would help families pay their bills (95%), improve access to care (95%), improve health (100%), and reduce the burden of uncompensated care on providers (100%).51 When asked about potential adverse effects of the Medicaid expansion, 14% said it could foster dependency, and 36% said it has the potential to “overload the health care system” and make it harder for other insured individuals to get needed care.52

When asked to name two potential barriers to access to care for new Medicaid beneficiaries in their state, the most common answers were a lack of specialty providers accepting Medicaid (50%) and disruptions in coverage over time (45%).53 A smaller share (27%) cited a lack of primary care providers accepting Medicaid and 18% indicated that “cultural or non-economic barriers”—such as language differences and attitudes towards healthcare—could interfere with access to services.54 Twenty-three percent of officials predicted no major access barriers for Medicaid beneficiaries in their states.55

In terms of the ACA’s 2013–2014 increase in primary care payment rates in Medicaid, the consensus among 67% of officials was that this policy would only produce a “small increase in the number of providers” accepting Medicaid in their states, with 24% predicting no impact at all, and only 10% expecting large increases in provider participation in Medicaid.56

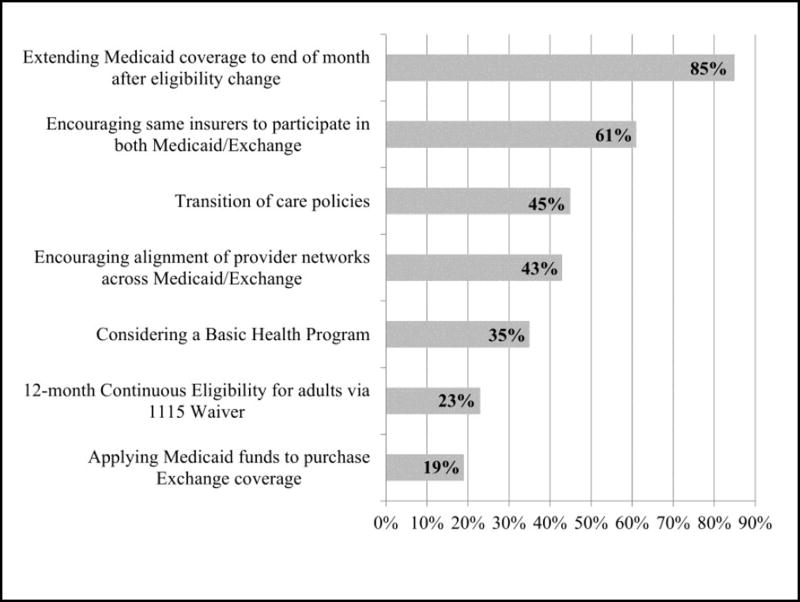

While disruptions in coverage over time were an important concern for officials, 64% of them agreed with the statement that enrollment and coverage in 2014 between Medicaid and the Exchange will be “well-integrated” in their state (71% for state-based Exchanges, 50% for the Federal Exchange, p=0.28).57 Figure 3 shows that states have taken a variety of approaches to address the impact of churning on continuity of coverage and care.58 Eighty-five percent of states plan to extend Medicaid coverage through the end of the month for people transitioning to Exchange plans, which many states were already doing in their standard managed care contracts.59 Sixty-one percent of states said that they have encouraged the same plans and insurers to participate in both Medicaid and the Exchange, and 43% have encouraged plans to adopt consistent provider networks across the different programs.60 More dramatic steps were being considered by a smaller number of states. Five states plan to adopt 12-month continuous eligibility for adults in Medicaid via an 1115 waiver, an option recently announced by CMS.61 Seven states are considering creating a Basic Health Program (BHP) in place of Exchange coverage for individuals up to 200% of the federal poverty level,62 and four states are planning to use Medicaid dollars to purchase Exchange coverage for all or some (e.g., pregnant women above 133% of the federal poverty level) Medicaid-eligible individuals—for instance, the so-called Arkansas model, in which the Medicaid expansion will occur almost entirely in the private market via Exchange coverage.63

D. Implementation Challenges

As shown in Table 6, when asked to identify the top two implementation challenges faced by their state, the most common responses from Medicaid officials were creating information technology systems to process applications (59%), coordinating coverage with the Exchanges (41%), and outreach and enrollment efforts (32%).64 Fewer officials identified delays in policy or legislative decision-making (14%) and converting to the Modified Adjusted Growth Income (MAGI) eligibility standard (14%) as key challenges.65

IV. DISCUSSION

In this survey of Medicaid directors and other program officials in states expanding Medicaid in 2014, we explored these officials’ intimate knowledge gained from overseeing state programs and their responsibility for programmatic success. In their responses to a wide-ranging exploration of current policy issues, we found a mix of cautious optimism and significant concerns. We expected officials in these states to be quite positively disposed towards the benefits of Medicaid expansion, but the picture that emerged was more nuanced. Expectations are optimistic regarding the law’s impact on coverage and access to care, but potential fault lines emerged related to the expansions’ costs.

Nearly three-quarters of state officials think it possible, likely, or nearly certain that the federal government will scale back its funding commitment, ultimately requiring greater expenditures by states to cover newly-eligible individuals.66 For 2014–2016, the ACA requires the federal government to pay 100% of these costs, making it nearly impossible for state costs to increase in the short-term, other than via a large woodwork effect.67 While the ACA envisions the FMAP declining to 90% by 2020,68 this is still far higher than the traditional Federal Medicaid match rate, which ranges from 50% to 75% for 2014 (depending on the state).69 Though Congress has never voted to cut the match rate (and has raised it temporarily on several occasions, most recently during the 2009 recession), the issue has become a point of contention among state and federal leaders debating the Medicaid expansion.70

Costs were not the only concern. A significant minority worried about deleterious impacts on access to care for previously insured populations, as the system strains to absorb additional demand from new beneficiaries.71 Similar concerns were voiced for previous coverage expansions, though one recent study of Medicare beneficiaries in Massachusetts found no adverse impact of that state’s expansion in 2007.72 Officials also worried about the availability of specialist physicians in Medicaid (and to a lesser extent primary care physicians).73 Few believed that the ACA’s primary care payment increase would have a significant impact,74 consistent with preliminary reports of limited effectiveness.75 These results suggest that payment changes alone (especially of a temporary nature) may be inadequate to increase the supply of physicians willing to treat patients with Medicaid, and other studies have shown that non-financial factors—such as administrative hassles and the social and clinical complexity of patients—also deter physicians from participating in Medicaid.76

Finally, officials anticipate challenges for beneficiaries based on frequent eligibility changes for Medicaid and Exchange coverage, as family incomes fluctuate.77 Despite 64% of officials indicating that the Exchanges and Medicaid will be well integrated in their states,78 many officials reported that coordination between Medicaid and the Exchange was a major implementation challenge.79 States are planning a variety of policies to improve continuity of care, ranging from encouraging the same health plans to participate in both markets to twelve-month continuous eligibility for adults or the creation of a BHP in 2015.80 These policy variations present an important opportunity for future research to elucidate which approaches are most effective at promoting stable coverage over time.

There were also areas where state Medicaid leaders were quite optimistic about the expansion. Predictions of enrollment among uninsured individuals were mostly between 50% and 75%.81 Enrollment estimates among eligible adults prior to the ACA range from 60% to 67%,82 but this includes significant numbers of disabled people who traditionally have higher participation rates.83 Thus, state officials predict enrollment among non-disabled adults who will make up the bulk of the expansion84 to be relatively high compared to past experience.85 These high projections may be in part because more than half of these states are not starting from scratch, instead converting previous state-based insurance programs into Medicaid coverage.86 While this transfer can pose administrative challenges,87 it should make it easier to target eligible individuals.

In terms of enrollment efforts, technical changes in the application process or IT systems were very common, while only about half of states were planning any kind of media outreach.88 Less than one-third of states are planning to facilitate Medicaid participation by enrolling individuals in Medicaid using their eligibility in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),89 but early reports from one state demonstrate how effective this approach can be: 56,000 newly eligible individuals (an estimated 10% of the state’s uninsured population) signed up for Oregon’s Medicaid program in the first half of October after their eligibility was determined based on enrollment in SNAP.90

Meanwhile, the most commonly voiced implementation challenge was the difficulty in creating IT systems to process applications, a concern that has proven prescient given the poor performance of the Federal Exchange and several state Exchanges during the initial open enrollment period.91 However, none of these officials reported that they were expecting most Medicaid applications to come via Healthcare.gov, instead either coming via state Exchanges or applications directly to the Medicaid agency.92 These predictions suggest that challenges experienced by the federal government’s website likely will have much less impact for 2014 on Medicaid enrollment compared to Exchange coverage. Moreover, the Federal Exchange website experienced a rapid improvement in functioning that was evident by early 2014, suggesting the website itself was not a major long-term barrier to enrollment.93 Whether Medicaid enrollment has been hampered in states with their own poorly functioning Exchange websites (such as Maryland, Minnesota, Massachusetts, and Oregon) remains unclear.94

In the domains of costs and access, state officials were bullish on Medicaid managed care. Most states reported that the vast majority of new enrollees will be in managed care, and not a single official voiced a concern that managed care networks or cost-sharing would pose significant barriers to care for beneficiaries.95 Furthermore, more than half of officials viewed the expansion of managed care as a key element in cost control.96 While consistent with national trends regarding the expansion of Medicaid managed care, this enthusiasm is not yet matched by the evidence, which has been equivocal on whether managed care reduces Medicaid costs.97

Finally, despite the focused areas of concern discussed above, officials were nearly unanimous that overall the Medicaid expansion would significantly improve low-income adults’ access to care, health, and financial circumstances.98

In conclusion, as roughly half of the nation prepares to expand Medicaid to millions of Americans in 2014, both challenges and opportunities abound. In many states embarking on the expansion, high-ranking state Medicaid officials remain concerned about the expansion’s impact on state spending, especially the possibility that the federal government will not maintain its promised share of costs.99 In this context, one key federal approach that could bolster state efforts is escaping the current cycle of fiscal crises that cast uncertainty over future federal commitments. State officials also identified several potential barriers to care for individuals once enrolled in the program, such as the availability of participating specialists in Medicaid and disruptions in insurance over time.100 Meanwhile, officials are optimistic about their states’ ability to get the majority of individuals enrolled in coverage, despite concerns about information technology.101 Overall, states are exploring a range of policy options to address these multifaceted concerns. As the expansions take effect over the coming years, future research will be critical to evaluate and improve upon these initial efforts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant number K02HS021291 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Sommers currently serves part-time as an advisor in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, at the HHS. This paper does not represent the views of HHS. We greatly appreciate the insights and information provided by state Medicaid officials in the study.

APPENDIX

A. Study Specifics

-

Expanding States

The following twenty-six states (including the District of Columbia, which we refer to as a “state” for brevity) comprised the study sample. Medicaid directors in each state were invited to participate in the survey. Twenty-three of the twenty-six states ultimately participated in the study (a response rate of 88.5%).

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

District of Columbia

Delaware

Hawaii

Illinois

Iowa

Kentucky

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Nevada

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Dakota

Ohio

Oregon

Rhode Island

Vermont

Washington

West Virginia

-

Survey Instrument102

- Which of the following do you see as potential benefits of expanding Medicaid to uninsured individuals? Select YES or NO for each option. Then, please indicate the option you see as the most important benefit of expanding Medicaid, if any.

Option Yes No Most

Importanta. Expanded Medicaid helps families pay their medical bills. b. It improves families’ access to health care. c. It improves health for its beneficiaries. d. It reduces the burden of uncompensated care on health care providers. -

Which of the following do you see as potential drawbacks of expanding Medicaid? Select YES or NO for each option.

Then, please indicate the option you see as the most important drawback of expanding Medicaid, if any.Option Yes No Most

Importanta. Expanding Medicaid will be costly to the state budget. b. It will foster dependency among beneficiaries. c. It will harm people by putting them in a flawed program. d. It will overload the health care system, and may make it harder for other insured individuals to get needed care. e. It will increase unwanted federal involvement in our health care system, in place of state or local oversight. -

Some state officials have raised concerns that the federal government will have to cut the match rate (FMAP) promised in the ACA, due to budget pressures. What do you think the likelihood is that this will occur in the next decade? (Choose ONE option)

Nearly impossible

Somewhat unlikely

Possible

Somewhat likely

Nearly certain

-

In 2013–2014, the Affordable Care Act requires Medicaid programs to pay Medicare rates for primary care physician services using federal dollars. What impact do you think this policy is having or will have in your state? (Choose ONE option)

No change in provider participation in Medicaid

Small increase in the number of providers willing to participate in Medicaid

Large increase in the number of providers willing to participate in Medicaid

-

Which of the following do you see as the most promising ways to control program costs in Medicaid? (Choose your TOP TWO options)

Restricting rates paid to providers

Limits on optional Medicaid benefits

Expanding Medicaid managed care

Scaling back Medicaid eligibility for certain groups

Increasing copayments

Implementing new payment models and/or new care delivery models

Other: ________________________________

- How would you describe the general level of support from the following stakeholders in your state towards expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act? Please circle one option from the scale for each stakeholder.

Strongly

OpposeOppose Neutral Support Strongly

Supporta. Physicians: 1 2 3 4 5 b. Hospitals: 1 2 3 4 5 c. Insurance Companies: 1 2 3 4 5 d. Patient Advocates: 1 2 3 4 5 e. Business Community: 1 2 3 4 5 -

Currently, only about 60–70% of adults who are currently eligible for Medicaid are enrolled in the program. Some have predicted that many uninsured but eligible individuals are likely to enroll in 2014, sometimes called the “woodwork effect.” Which of the following most closely matches your perspective on this issue in your state? (Choose ONE option):

“I do not expect that the ACA will bring previously eligible individuals into Medicaid.”

“I expect that the ACA will bring a small number of previously eligible individuals into Medicaid.”

“I expect that the ACA will bring in a moderate number of previously eligible individuals into Medicaid.”

“I expect that the ACA will bring in a large number of previously eligible individuals into Medicaid.”

-

Please circle ONE option below to indicate the degree to which you agree with the following statement:

“Enrollment and coverage in 2014 between Medicaid and the Exchange will be well-integrated in our state.”Strongly

DisagreeDisagree Neutral Agree Strongly

Agree1 2 3 4 5 -

Among uninsured adults who will become newly-eligible for Medicaid in your state, what percentage of them do you think will sign up in 2014? (Do NOT include previous Medicaid-based expansions your state may have already implemented).

(Choose ONE option):

Less than half (0–49%)

Between half and three-quarters (50–75%)

Between three-quarters and 90% (76–90%)

More than 90%

-

Does your state have a pre-existing state- or locally-funded insurance program for low-income adults that will be replaced in part or in full by the Medicaid expansion in 2014? (Do NOT include previous Medicaid-based expansions your state may have already implemented).

Yes – Name of Program: ___________ , then Go to QUESTION 11

No – SKIP to QUESTION 12

-

What percentage of your state’s expected new Medicaid enrollment in 2014 will come from individuals currently participating in pre-existing state or local insurance program(s)? (Choose ONE option)

Less than 25%

Between 25% and 50%

Between 50% and 75%

More than 75%

-

Of the following policy-related factors, which will have the largest impact on whether newly-eligible individuals sign up for Medicaid coverage in your state? (Choose ONE option):

How easy or difficult the application process is

Adequate staffing to handle the volume of applications

The quality of the Medicaid program

Public education to inform people about the new coverage option

Active outreach and community-based assistance with applying (including enrolling people who already interact with the health care safety net)

- Which of these steps, if any, has your state already taken or will take by 2014 to facilitate new Medicaid enrollment? (Check all that apply).

Options Yes No a. Increasing administrative staff capacity to process applications b. Investing in new eligibility systems and information technology (IT) c. Using administrative data (e.g. for income, citizenship) to reduce paperwork burden for new applications and renewals d. Enrolling individuals into Medicaid based on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) eligibility e. Facilitate enrollment of parents based on income eligibility of their children in Medicaid or CHIP f. Setting up active enrollment facilitators in the community and/or conducting “in-reach” to enroll people who have already interacted with the health care safety net g. Conducting a media campaign to increase awareness of the expansion -

What do you think will be the primary pathway of enrollment through which newly eligible individuals will gain Medicaid coverage? (Choose ONE option):

Individuals applying directly through the state Medicaid agency

Individuals applying directly through the Exchange/Marketplace

Through insurance brokers

Through Navigators or other application assistance services (including the assistance of health care providers)

-

What do you think will be the greatest barrier to care for new Medicaid beneficiaries in your state? (Choose up to TWO options)

Lack of primary care providers who will accept Medicaid patients

Lack of specialty providers who will accept Medicaid patients

Inability to afford cost-sharing and copays

Restrictive managed care networks

Benchmark coverage may leave out important benefits

Cultural or non-economic barriers

Churning or disruptions in coverage over time

None of the above - barriers to care will not be a problem

-

What percentage of the newly-eligible Medicaid population in your state do you expect will be in managed care plans? (Choose ONE option):

0%

1% – 25%

26% – 50%

51% – 75%

76% – 99%

100%

-

Which of the following most closely matches your perspective about the impact of the Medicaid expansion on your state’s direct spending towards uncompensated care (such as state funding for mental health and substance abuse services, community health centers, public hospitals, and medical care for prisoners. Do NOT include Medicaid or DSH-related expenses)? (Choose ONE option)

No impact on state spending for uncompensated care

Small reduction in state spending for uncompensated care

Medium reduction in state spending for uncompensated care

Large reduction in state spending for uncompensated care

-

Taking into account potential savings from reduced state spending on uncompensated care and/or from existing state insurance programs, balanced against the state’s share of additional costs from expanded Medicaid coverage, do you expect the Medicaid expansion over the next decade will:

Impose a cost to the state budget

Be budget-neutral for the state

Result in savings for the state budget

- Researchers have predicted that many people will experience frequent changes in eligibility, potentially requiring them to switch back and forth between Medicaid and Qualified Health Plans sold through insurance Exchanges. What measures, if any, has your state taken or plan to take to address this issue in 2014? (Check all that apply):

Options Yes No a. Encouraging the same insurers to participate in both Medicaid and Exchanges b. Encourage plans to align provider networks across the two programs c. Using the new option recently announced by CMS of a 12-month continuous eligibility period for adults in Medicaid, under a Section 1115 waiver d. Exploring the option of creating a Basic Health Program to cover all adults up to 200% of the federal poverty level e. Using Medicaid funds to cover newly-eligible adults in Exchange plans, instead of traditional coverage f. Requiring transition-of-care policies related to treatment and provider choice between Medicaid and Exchange plans, for some or all beneficiaries g. Extending Medicaid coverage through the end of the month for people transitioning to Exchange plans -

Please circle ONE option below to indicate the degree to which you agree with the following statement:

“Our state Medicaid department is equipped with the necessary funds and resources to manage the influx of newly-eligible individuals come 2014”.Strongly

DisagreeDisagree Neutral Agree Strongly

Agree1 2 3 4 5 -

What do you see as your state’s two biggest implementation challenges for the 2014 Medicaid expansion? (Choose your TOP TWO options.)

Outreach and enrollment efforts

Coordinating coverage with the Exchange

Converting to the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) eligibility standard

Ensuring provider adequacy for new Medicaid beneficiaries

Meeting the needs of newly-eligible individuals with chronic health conditions

Reduction in Disproportionate Share (DSH) payments to hospitals

Controlling Medicaid program costs

Creating information technology (IT) systems to process applications

Delays in state legislative or policy decision-making

-

In which of the areas listed in the previous question would your state benefit the most from technical assistance, either from external consultants and/or CMS?

(Choose up to TWO options.)

Outreach and enrollment efforts

Coordinating coverage with the Exchange

Converting to the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) eligibility standard

Ensuring provider adequacy for new Medicaid beneficiaries

Meeting the needs of newly-eligible individuals with chronic health conditions

Reduction in Disproportionate Share (DSH) payments to hospitals

Controlling Medicaid program costs

Creating information technology (IT) systems to process applications

Delays in state legislative or policy decision-making

B. Figure Appendix

Figure 1.

State Enrollment and Outreach Strategies103

Figure 2.

Predicted Cost Impact of Medicaid Expansion and Likelihood of Reduction in the Federal Match Rate Over the Next Decade104

Figure 3.

State Strategies to Stabilize Coverage and Prevent Disruptions in Care105

C. Table Appendix

Table 1.

State Medicaid Officials’ Expectations Regarding Medicaid Enrollment106

| Survey Item | Number |

|---|---|

| Predicted take-up of Medicaid among newly-eligible adults | |

| — Less than 50% | 3 (14%) |

| — Between 50 and 75% | 16 (76%) |

| — Between 76% and 90% | 2 (10%) |

| — Greater than 90% | 0 (0%) |

| Predicted impact of the ACA on Medicaid enrollment among previously-eligible uninsured individuals (the “woodwork effect”) | |

| — No effect | 0 (0%) |

| — Small number of previously eligible individuals will enroll | 6 (27%) |

| — Moderate number of previously eligible individuals will enroll | 15 (68%) |

| — Large number of previously eligible individuals will enroll | 1 (5%) |

| State has a pre-existing state- or locally-funded insurance program for low-income adults that will be replaced by the ACA expansion | |

| — Yes | 12 (55%) |

| — No | 10 (45%) |

| Of those with pre-existing programs, percentage of 2014 expansion enrollment expected to come from individuals currently in those programs | |

| — Less than 25% | 6 (50%) |

| — Between 25% and 50% | 2 (17%) |

| — Between 51% and 75% | 3 (25%) |

| — More than 75% | 1 (8%) |

| Most important determinant of take-up among newly-eligible individuals | |

| — Active outreach and community-based assistance with applying | 13 (59%) |

| — Public education | 4 (18%) |

| — Adequate staffing to handle application volume | 3 (14%) |

| — Ease of application process | 1 (5%) |

| — Quality of the Medicaid program | 0 (0%) |

| Medicaid department staffing and resource adequacy for 2014a | |

| — Agree that staffing and resources are adequate | 13 (59%) |

| — Disagree that staffing and resources are adequate | 4 (18%) |

| — Neither agree nor disagree | 5 (23%) |

| Primary expected pathway for Medicaid enrollment in 2014 | |

| — Through the state Medicaid agency | 10 (45%) |

| — Through the Exchange | 5 (23%) |

| — Through navigators or other application assistance services | 5 (23%) |

| — Through single integrated Medicaid-Exchange interfaceb | 2 (9%) |

| — Through insurance brokers | 0 (0%) |

Officials were asked to respond on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” for the following statement: “Our state Medicaid department is equipped with the necessary funds and resources to manage the influx of newly-eligible individuals come 2014.” We collapsed these categories into three for brevity.

This was not an original option on the survey instrument, but two states answered this, explaining that there would be no distinction between the Medicaid and Exchange enrollment process in their states.

Table 2.

State Medicaid Officials’ Expectations Regarding Application Pathway, by State Exchange Type107

| Expected Application Pathway for Most Individuals Newly-Eligible for Medicaid |

Exchange Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Exchange |

State- Based Exchanges |

P-value for difference |

|

| Through the state Medicaid agency | 8 (100%) | 2 (14%) | 0.002 |

| Through single integrated Medicaid-Exchange interfacea | 0 (0%) | 2 (14%) | |

| Through the Exchange | 0 (0%) | 5 (36%) | |

| Through insurance brokers | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Through navigators or other application assistance services | 0 (0%) | 5 (36%) | |

This was not an original option on the survey instrument, but two states answered this, explaining that there would be no distinction between the Medicaid and Exchange enrollment process in their states.

Table 3.

State Medicaid Officials’ Expectations Regarding Costs and the Medicaid Expansion108

| Survey Item | Number |

|---|---|

| Effect of Medicaid expansion on your state’s budget over next decade | |

| — Impose a cost to the state budget | 6 (29%) |

| — Be budget neutral for the state | 3 (14%) |

| — Result in savings for the state budget | 12 (57%) |

| Likelihood of federal government reducing the match rate (FMAP) in the next decade | |

| — Nearly impossible | 4 (18%) |

| — Somewhat unlikely | 2 (9%) |

| — Possible | 10 (45%) |

| — Somewhat likely | 5 (23%) |

| — Nearly certain | 1 (5%) |

| Impact of the Medicaid expansion on state spending for uncompensated care | |

| — No impact | 1 (5%) |

| — Small reduction in state spending | 8 (36%) |

| — Medium reduction in state spending | 11 (50%) |

| — Large reduction in state spending | 2 (9%) |

| Most promising approaches for controlling program costsa | |

| — Implementing new payment models and/or new care delivery models | 21 (95%) |

| — Expanding Medicaid managed care | 12 (55%) |

| — Otherb | 8 (36%) |

| — Increasing copayments | 1 (5%) |

| — Limits on optional Medicaid benefits | 0 (0%) |

| — Scaling back Medicaid eligibility for certain groups | 0 (0%) |

| — Restricting rates paid to providers | 0 (0%) |

| Proportion of newly-eligible individuals who will be in Medicaid managed care | |

| — 0% | 1 (5%) |

| — 1–25% | 0 (0%) |

| — 26–50% | 0 (0%) |

| — 51–75% | 1 (5%) |

| — 76–99% | 11 (50%) |

| — 100% | 9 (41%) |

Officials were asked to select up to two options for this item.

“Other”: approaches included improved fraud-detection, educating providers about cost-effectiveness, and incentivizing healthy behaviors for patients.

Table 4.

State Medicaid Officials’ Expectations Regarding Costs of the Medicaid Expansion, Stratified by Overall Budget Predictions109

| Survey Item | Prediction of Medicaid Expansion’s State Budget Impact Over the Next Decade |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Costly to State Budget |

Savings for State Budget |

P-value | |

| Effect of Medicaid Expansion on Spending on Uncompensated Care | |||

| — No impact | 1 (17%) | 0 (0%) | 0.67 |

| — Small reduction | 1 (17%) | 4 (33%) | |

| — Medium reduction | 4 (67%) | 7 (58%) | |

| — Large reduction | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | |

| Predicted impact of the ACA on Medicaid enrollment among previously-eligible uninsured individuals (the “woodwork effect”) | |||

| — No effect | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.17 |

| — Small number of previously eligible individuals will enroll | 0 (0%) | 5 (42%) | |

| — Moderate number of previously eligible individuals will enroll | 6 (100%) | 6 (50%) | |

| — Large number of previously eligible individuals will enroll | 0 (0%) | 1 (8%) | |

| State has a pre-existing state- or locally-funded insurance program for low-income adults that will be replaced by the ACA expansion | |||

| — Yes | 2 (33%) | 8 (67%) | 0.18a |

| — No | 4 (67%) | 4 (33%) | |

| Of those with pre-existing programs, percentage of 2014 expansion enrollment expected to come from individuals currently in those programs | |||

| — Less than 25% | 1 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 0.89a |

| — Between 25% and 50% | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| — Between 50% and 75% | 1 (50%) | 3 (38%) | |

| — More than 75% | 0 (0%) | 1 (12%) | |

| Likelihood of federal government reducing the match rate (FMAP) in the next decade | |||

| — Nearly impossible | 0 (0%) | 3 (25%) | 0.02 |

| — Somewhat unlikely | 0 (0%) | 2 (17%) | |

| — Possible | 2 (33%) | 5 (42%) | |

| — Somewhat likely | 3 (50%) | 2 (17%) | |

| — Nearly certain | 1 (17%) | 0 (0%) | |

A measure combining the question on the existence of a pre-existing program with the percentage of enrollment expected from that program also did not differ significantly across the two groups, p=0.21.

Table 5.

State Medicaid Officials’ Expectations Regarding Access to Care in Medicaid110

| Survey Item | Number |

|---|---|

| Benefits of expanded Medicaid (Yes/No for each) | |

| — Improves families’ access to health care | 21 (95%) |

| — Reduces the burden of uncompensated care on health care providers | 22 (100%) |

| — Improves health for its beneficiaries | 21 (100%) |

| — Helps families pay their medical bills | 21 (95%) |

| Drawbacks of expanded Medicaid (Yes/No for each) | |

| — It will overload the health care system, and may make it harder for other insured individuals to get needed care | 8 (36%) |

| — It will foster dependency among beneficiaries | 3 (14%) |

| — It will harm people by putting them in a flawed program | 1 (5%) |

| Greatest barrier(s) to care for new Medicaid beneficiaries in your statea | |

| — Lack of specialty providers who accept Medicaid | 11 (50%) |

| — Churning or disruptions in coverage over time | 10 (45%) |

| — Lack of primary care providers accepting Medicaid | 6 (27%) |

| — Cultural or non-economic barriers | 4 (18%) |

| — Inability to afford cost-sharing and copays | 0 (0%) |

| — Restrictive managed care networks | 0 (0%) |

| — Benchmark coverage may leave out important benefits | 0 (0%) |

| — Barriers to care will not be a problem | 5 (23%) |

| Impact of the primary care Medicaid payment increase for 2013–2014 on physician participation rates in Medicaid in your state | |

| — No impact | 5 (24%) |

| — Small impact | 14 (67%) |

| — Large impact | 2 (10%) |

Officials were asked to select up to two options for this item.

Table 6.

State Medicaid Officials’ Views of the Biggest Implementation Challenges for the 2014 Expansion111

| Survey Item | Number |

|---|---|

| Creating information technology (IT) systems to process applications | 13 (59%) |

| Coordinating coverage with the Exchange | 9 (41%) |

| Outreach and enrollment efforts | 7 (32%) |

| Converting to the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) eligibility standard | 3 (14%) |

| Delays in state legislative or policy decision-making | 3 (14%) |

| Controlling Medicaid program costs | 3 (14%) |

| Meeting the needs of newly-eligible individuals with chronic health conditions | 3 (14%) |

| Ensuring provider adequacy for new Medicaid beneficiaries | 2 (9%) |

| Reduction in Disproportionate Share (DSH) payments to hospitals | 0 (0%) |

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to report.

Of note, this is the full survey instrument, excluding the description of the study and background information for participants. Not all items below were presented in the paper due to space constraints.

Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Full survey sample size, N=23. IT: Information Technology; CHIP: Children’s Health Insurance Program; SNAP: Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, formerly known as “food stamps.”

Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Full survey sample size, N=23.

Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Full survey sample size, N=23.

Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Full survey sample size, N=23.

Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Full survey sample size, N=23. “Federal Exchange” includes states with Federal-State Partnership Exchanges (5) and the Federally-Facilitated Exchange (1). P-value is based on chi-square test comparing all categories, by federal versus state-based Exchanges.

Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Full survey sample size, N=23.

Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Numbers may not sum to 100% due to rounding. 3 states answering that they expect the Medicaid expansion to be “Budget Neutral” were excluded from this stratified analysis, but are included in the full sample data in reported in Table 3.

Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Full survey sample size, N=23. Totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Officials were asked to select up to two options for this item. Percentages for each question exclude item non-response. Full survey sample size, N=23. Totals may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

References

- 1.Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision, 2014. Kaiser Family Found. http://kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/ (last updated Jan. 28, 2014)

- 2.See discussion infra Parts III.A–C (discussing survey results regarding Medicaid enrollment, costs, and access).

- 3.Kenney Genevieve M, et al. Variation in Medicaid Eligibility and Participation Among Adults: Implications for the Affordable Care Act. Inquiry. 2012;49:231, 236. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_49.03.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindeman Ralph. State Medicaid Agencies Reporting Problems in New Exchange-Linked Enrollment System. Bloomberg BNA. 2013 Oct 16; http://www.bna.com/state-medicaid-agencies-n17179878209/

- 5.Sommers Benjamin D, Epstein Arnold M. Why States are So Miffed About Medicaid— Economics, Politics, and the “Woodwork Effect,”. New Eng. J. Med. 2013;365:100, 100–02. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1104948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sonier Julie, et al. Medicaid ‘Welcome-Mat’ Effect of Affordable Care Act Implementation Could Be Substantial. Health Aff. 2013;32:1319, 1319–20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sommers Benjamin D, Epstein Arnold M. U.S. Governors and the Medicaid Expansion—No Quick Resolution in Sight. New Eng. J. Med. 2013;368:496, 498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See Baicker Katherine, et al. The Oregon Experiment—Effects of Medicaid on Clinical Outcomes. New Eng. J. Med. 2013;368:1713, 1713–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321.; Sommers Benjamin D, et al. Mortality and Access to Care among Adults after State Medicaid Expansions. New Eng. J. Med. 2012;367:1025, 1025. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1202099.; Finkelstein Amy, et al. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year. :28–29. (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Research, Working Paper No. 17190, 2011).

- 8.Cunningham Peter J. Ctr. For Health Sys. Change, State Variation in Primary Care Physician Supply: Implications for Health Reform Medicaid Expansions. 2012:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Decker Sandra L. Two-Thirds of Primary Care Physicians Accepted New Medicaid Patients in 2011–12: A Baseline to Measure Future Acceptance Rates. Health Aff. 2012;32:1183, 1183–87. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Decker Sandra L. In 2011 Nearly One-Third of Physicians Said They Would Not Accept New Medicaid Patients, but Rising Fees May Help. Health Aff. 2012;31:1673, 1673–79. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buettgens Matthew, et al. Urban Inst., Churning Under the ACA and State Policy Options for Mitigation. 2011;3 available at http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412587-Churning-Under-the-ACA-and-State-Policy-Options-for-Mitigation.pdf. [Google Scholar]; Sommers Benjamin D, Rosenbaum Sara. Issues in Health Reform: How Changes in Eligibility May Move Millions Back and Forth Between Medicaid and Insurance Exchanges. Health Aff. 2011;30:228, 228–36. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.See generally Letter from Cindy Mann, Dir., Ctrs. for Medicaid & CHIP Servs., to State Health Official and Medicaid Dir., (May 17, 2013) (on file with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services).

- 11.See Sommers & Epstein, supra note 6, at 496–99.

- 12.See generally Heberlein Martha, et al. Kaiser Family Found., Getting into Gear for 2014: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP, 2012–2013. 2013 available at http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/8401.pdf.; Smith Vernon K, et al. Kaiser Family Found., Medicaid in a Historic Time of Transformation: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2013 and 2014. 2013 available at http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/8498-medicaid-in-a-historic-time-of-transformation.pdf..

- 13.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 14.See infra Part V.B. Figure 2.

- 15.See infra Part V.C. Table 3.

- 16.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 17.See infra Part V.A.1., for a complete list of states that have chosen to implement the Medicaid expansion. Of note, this survey reports the results of the District of Columbia as a state for simplicity’s sake. The Center for Health Care Strategies is a non-profit organization that provides technical assistance to state Medicaid officials across the country.

- 18.As our study consisted of interviews with public officials about their public roles, it was exempted from review by the Harvard Institutional Review Board (IRB); see also generally 45 C.F.R. § 46 (2013).

- 19.See, e.g Sparer Michael. Robert Wood Johnson Found., Medicaid Managed Care: Costs, Access, and Quality of Care. 2010 available at http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/reports/2012/rwjf401106.; Kenney Genevieve M, et al. A Decade of Health Care Access Declines for Adults Holds Implications for Changes in the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff. 2010;31:899, 899–908. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0159.; Sommers Benjamin D, Epstein Arnold M. Medicaid Expansion—the Soft Underbelly of Health Care Reform? New Eng. J. Med. 2010;363:2085, 2085–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1010866..

- 20.Sommers Benjamin D, et al. Lessons from Early Medicaid Expansions Under Health Reform: Interviews with Medicaid Officials. Medicare & Medicaid Res. Rev. 2013;3:E1, E1–E23. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.04.a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.See infra Part V.A.2. for the full survey instrument.

- 22.See Kaiser Family Found., supra note 1.

- 23.See infra Part V.A.1.

- 24.See infra Part V.A.2.

- 25.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 26.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 27.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 28.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 29.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 30.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 31.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 32.See infra Figure 1.

- 33.See infra Part V.C. Tables 1, 2.

- 34.See infra Part V.C. Table 2.

- 35.See infra Part V.C. Table 2.

- 36.See infra Part V.C. Table 2.

- 37.See infra Part V.B. Figure 2.

- 38.See infra Part V.B. Figure 2.

- 39.See infra Part V.C. Tables 3, 4.

- 40.See infra Part V.C. Tables 3, 4.

- 41.See infra Part V.C. Table 3.

- 42.See infra Part V.C. Table 4.

- 43.See infra Part V.C. Table 4.

- 44.See infra Part V.C. Table 4.

- 45.See infra Part V.C. Table 4.

- 46.See infra Part V.C. Table 3.

- 47.See infra Part V.C. Table 3.

- 48.See infra Part V.C. Table 3.

- 49.See infra Part V.C. Table 4.

- 50.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 51.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 52.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 53.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 54.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 55.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 56.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 57.This survey item is not reported in the Tables.

- 58.See infra Part V.B. Figure 3.

- 59.See infra Part V.B. Figure 3.

- 60.See infra Part V.B. Figure 3.

- 61.See Mann, supra note 10, at 3.

- 62.Hwang Ann, et al. Creation of State Basic Health Programs Would Lead to 4 Percent Fewer People Churning Between Medicaid and Exchanges. Health Aff. 2012;31:1314, 1314. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0986.. Section 1331 of the ACA allowed states to create BHPs to cover individuals who might fall just above and below the Medicaid eligibility line, and also to cover individuals who were lawfully present not citizens with incomes below 133% of the federal poverty line. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 § 1331, 42 U.S.C. § 18051 (2012).

- 63.Rosenbaum Sara, Sommers Benjamin D. Using Medicaid to Buy Private Health Insurance— The Great New Experiment? New Eng. J. Med. 2013;369:7, 7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1304170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.See infra Part V.C. Table 6.

- 65.See Infra Part V.C. Table 6.

- 66.See infra Part V.B. Figure 1 (illustrating that approximately 45% of officials voted possible, 23% voted likely, and 5% voted nearly certain).

- 67.Cf. Dorn Stan, Buettgens Matthew, Inst Urban. Net Effects of the Affordable Care Act on State Budgets. 2010;1 available at http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/1001480-Affordable-Care-Act.pdf. (asserting that state costs are expected to increase due to an expected woodwork effect and a gradual decline in the federal share beginning in 2017, even though newly eligible adults will be covered by the federal government from 2014–2016).

- 68.Id. at 1.

- 69.See Federal Financial Participation in State Assistance Expenditures for Fiscal Year 2014, 77 Fed. Reg. 71,420, 71,422 (Nov. 30, 2012) (reporting a minimum match rate of 50.00% for Alaska and other similarly situated states and a maximum match rate of 73.05% for Mississippi).

- 70.See Sommers, supra note 6, at 496, 498–99 (noting that some governors expressed concern that the federal government will “scale back its share of Medicaid spending” in the future).

- 71.See infra Table 5 (reporting that 36% of the officials believe that the Medicaid expansion will overload the healthcare system).

- 72.See Joynt Karen E, et al. Insurance Expansion in Massachusetts Did Not Reduce Access Among Previously Insured Medicare Patients. Health Aff. 2013;32:571, 576. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1018. (finding that the insurance expansion did not have a negative effect on preventable hospitalizations).

- 73.See infra Part V.C. Table 5 (reporting that 50% of the officials believe that a lack of specialists was one of the greatest barriers to care).

- 74.See infra Part V.C. Table 5 (reporting that 10% of the officials believe the payment increase would have a “large impact” on physician participation rates).

- 75.Bricklin-Small David, McGinnis Tricia. Improving the Medicaid Primary Care Rate Increase. Commonwealth Fund Blog. 2013 May 16; http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Blog/2013/May/Ways-to-Improve-Upon-the-Medicaid-Primary-Care-Rate-Increase.aspx. (“[I]t is not clear whether the gains [of the payment rate increase] will extend beyond the increase’s two-year time frame.”).

- 76.Sommers Anna S, et al. Physician Willingness and Resources to Serve More Medicaid Patients: Perspectives from Primary Care Physicians. Medicare & Medicaid Res. Rev. 2011;1:E1, E14. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.001.02.a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.See infra Part V.C. Table 5 (reporting that 45% of the officials believe that churning was one of the greatest barriers to care for new Medicaid beneficiaries).

- 78.This item is unreported in Part V, infra.

- 79.See infra Part V.C. Table 6 (reporting that 41% of the officials believe that coordinating coverage with the exchange will be the biggest implementation challenge of the 2014 expansion).

- 80.See infra Part V.B. Figure 3.

- 81.See infra Part V.C. Table 1 (reporting that 76% of officials believe that the “[p]redicted take-up of Medicaid among newly-eligible adults” is between 50% and 75%).

- 82.See Kenney, supra note 3, at 244–45 (reporting that the eligible adult enrollment estimates by state were highly variable, ranging from 51% to 93%); see also Sommers, supra note 19, at 2085 (reporting that the eligible adult enrollment estimates were highly variable, ranging from 44% to 88%).

- 83.See Sommers Benjamin D, et al. Reasons for the Wide Variation in Medicaid Participation Rates Among States Hold Lessons for Coverage Expansion in 2014. Health Aff. 2012;31:909, 912. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0977. (finding that the “strongest predictor of Medicaid take-up was category of eligibility” and that the category of disabled adults signaled a significantly higher probability of Medicaid enrollment).

- 84.See Kenney Genevieve M, Inst Urban, et al. Opting in to the Medicaid Expansion Under the ACA: Who Are the Uninsured Adults Who Could Gain Health Insurance Coverage? 2012:1. available at www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/412630-opting-in-medicaid.pdf..

- 85.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 86.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.

- 87.See Sommers, supra note 19, at E14.

- 88.See infra Part V.B. Figure 1.

- 89.See infra Part V.B. Figure 1.

- 90.See Budnick Nick. Oregon Cuts Tally of People Lacking Health Insurance by 10 Percent in Two Weeks. Oregonian. 2013 Oct 17; http://www.oregonlive.com/health/index.ssf/2013/10/oregon_has_cut_tally_of_those.html..

- 91.See infra Part V.C. Table 6.

- 92.See infra Part V.C. Table 2.

- 93.Stewart Martina. Administration: Obamacare Website Working. Smoothly, CNN. 2013 Dec 1; http://www.cnn.com/2013/12/01/politics/obamacare-website/

- 94.Pear Robert. State Officials Cite Technology Problems on Health Insurance Sites. N.Y. Times. 2014 Apr 3; http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/04/us/state-officials-cite-technology-problems-on-health-insurance-sites.html?_r=0.

- 95.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 96.See infra Part V.C. Table 3.

- 97.See Sparer, supra note 18, at 3.

- 98.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 99.See infra Part V.C. Table 3.

- 100.See infra Part V.C. Table 5.

- 101.See infra Part V.C. Table 1.