Abstract

Purpose

To determine potential associations between histologic features of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and estimated quantitative magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) parameters.

Methods

This prospective, cross-sectional study was performed as part of the Magnetic Resonance Assessment Guiding NAFLD Evaluation and Treatment (MAGNET) ancillary study to the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN). Sixty-four children underwent a 3T DWI scan (b-values: 0, 100, and 500 s/mm2) within 180 days of a clinical liver biopsy of the right hepatic lobe. Three parameters were estimated in the right hepatic lobe: apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), diffusivity (D), and perfusion fraction (F), the first assuming exponential decay and the latter two assuming bi-exponential intravoxel incoherent motion. Grading and staging of liver histology were done using the NASH CRN scoring system. Associations between histologic scores and DWI-estimated parameters were tested using multivariable linear regression.

Results

Estimated means ± standard deviations were: ADC: 1.3 (0.94 –1.8) x 10−3 mm2/s; D: 0.82 (0.56 – 1.0) x 10−3 mm2/s; and F: 17 (6.0 – 28) %. Multivariate analyses showed ADC and D decreased with steatosis and F decreased with fibrosis (p<0.05). Associations between DWI-estimated parameters and other histologic features were not significant: ADC-fibrosis (p=0.12), -lobular inflammation (p=0.20), -portal inflammation (p=0.27), -hepatocellular inflammation (p=0.29), -NASH (p=0.30); D-fibrosis (p=0.34), -lobular inflammation (p=0.84), -portal inflammation (p=0.76), -hepatocellular inflammation (p=0.38), -NASH (p=0.81); F-steatosis (p=0.57), -lobular inflammation (p=0.22), -portal inflammation (p=0.42), -hepatocellular inflammation (p=0.59), -NASH (p=0.07).

Conclusions

In children with NAFLD, steatosis and fibrosis have independent effects on DWI-estimated parameters ADC, D, and F. Further research is needed to determine the underlying mechanisms and clinical implications of these effects.

Keywords: NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, children, pediatric, DWI, ADC, intravoxel incoherent motion, quantitative imaging biomarkers, QIBs

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has emerged as the most common cause of chronic liver disease in children in the United States [1]. Currently, the clinical reference standard for evaluation of NAFLD and its progressive variant, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), is histologic assessment [2]. However, histologic assessment requires biopsy which is invasive and carries risks including pain and bleeding [3]. Therefore, quantitative non-invasive methods are desired for evaluation of NAFLD and NASH in children.

MR diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) is one promising non-invasive evaluative technique. DWI detects incoherent motion of water protons diffusing and perfusing through tissue [4, 5]. This motion depends on tissue microstructure and is affected by degree of cellularity [6], volume of extracellular space [7], and composition of cellular membranes [8]. Chronic pediatric liver diseases such as NAFLD can alter tissue microstructure, thereby affecting incoherent motion [4, 5]. DWI parameters are sensitive to incoherent motion and therefore may provide insight into microstructural alterations.

Numerous studies have shown that DWI parameters are associated with fibrosis [9–14] and inflammation [10, 12, 14] in viral hepatitis. More recent studies have shown significant associations between some histologic features of NAFLD (steatosis [15–19], fibrosis [15, 20], and inflammation [19]) and quantitative DWI parameters in adults. The generalizability of these findings to pediatric NAFLD is unclear, however, because the dominant pattern of NASH in children differs from that in adults [21]. The pediatric pattern is characterized by portal inflammation and/or fibrosis without the ballooning degeneration and perisinusoidal fibrosis typical of adult NASH [21]. The microstructural differences between pediatric and adult patterns of NASH may affect associations of histologic features and DWI parameters. Additionally, MR imaging is more difficult to perform in children due to variability in breath holding capacity, body habitus, and exam tolerability [22]. For these reasons the relationship between histology and DWI in children with NAFLD is uncertain.

Therefore, this study evaluated associations between histologic features of NAFLD and estimated quantitative DWI parameters in children.

Materials and Methods

Design

This prospective, cross-sectional, observational, single-site study was performed as part of the Magnetic Resonance Assessment Guiding NAFLD Evaluation and Treatment (MAGNET) ancillary study to the Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Clinical Research Network (NASH CRN). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and compliant with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Sixty-four pediatric participants aged 8–17 yrs from the [Institution withheld during submission to maintain blinding] NASH CRN clinical center were enrolled. Pediatric subjects gave written assent with parental or guardian written informed consent. Inclusion criteria for this study included enrollment in the NASH CRN and willingness and ability to undergo research MRI within a 180-day window of clinical-care right-hepatic-lobe percutaneous biopsy. No pharmaceutical treatments were administered during this window [23]. This window was chosen based on a previous study in adults with NAFLD who received no pharmaceutical treatment over this time frame in which no significant changes in liver histology were found [24]. As participants in the NASH CRN, all children had confirmed NAFLD with extensive clinical and laboratory phenotyping by NASH CRN investigators to exclude chronic alcohol consumption, exposure to hepatotoxic drugs, and other causes of chronic liver disease [25, 26].

Liver Biopsies and Histologic Grading

Liver biopsies were performed following clinical standard-of-care guidelines [23]. Tissue was fixed, embedded and sectioned according to routine methods and H&E and Masson’s trichrome stained slides prepared. Biopsies were reviewed at a multiheaded scope during a meeting of the pathologists of the NASH CRN pathology committee and a consensus histologic assessment determined for each of the following parameters (with corresponding ordinal scales): fibrosis stage (0–4), steatosis grade (0–3), lobular inflammation (0–3), portal inflammation (0–2), and hepatocellular ballooning (0–2). Each biopsy was given an overall diagnosis of definite steatohepatitis, possible/borderline steatohepatitis or not steatohepatitis. For analysis, borderline cases were classified with definite steatohepatitis cases.

Image Acquisition

To limit possible postprandial effects, children were asked to fast for four hours. They were positioned feet first with a torso phased-array coil centered over the liver and a dielectric pad placed between the coil and the abdominal wall. Diffusion-weighted spin-echo echo-planar imaging was performed during free breathing at 3T (Signa Excite scanner, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, Wisconsin) at three b-values: b=0, 100, and 500 s/mm2. Multiple single-excitation magnitude-only images were acquired for each b-value using 8, 16, and 32 repetitions, respectively. Images were acquired with spectral inversion at lipid (SPECIAL) fat suppression and water-selective excitation. Detailed sequence parameters are provided in Table 1a. Total imaging time was approximately 2.8 minutes. Respiratory and cardiac gating was not performed to keep acquisition time reasonably short.

Table 1.

| a) Diffusion-weighted imaging sequence parameters

| |

|---|---|

| Parameter | Values |

| Pulse sequence | Diffusion-weighted spin-echo echo-planar-imaging |

| Slice thickness | 10 mm |

| Interslice gap | 2 mm |

| TE | 45 ms |

| TR | 3,000 ms |

| Image matrix | 112 x 112 |

| FOV | 40 x 40 cm |

| Partial fourier acquisition | 75 % |

| Parallel imaging accelerating factor | 2 |

| b) Fat quantification imaging sequence parameters

| |

|---|---|

| Parameter | Values |

| Pulse sequence | Spoiled GRE, MRI-M |

| Slice thickness | 8 mm |

| Interslice gap | 0 mm |

| TE | 1.15, 2.30, 3.45, 4.60, 5.75, 6.90 ms |

| TR | 120 – 270 ms |

| Flip angle | 10° |

| Image matrix range | 160 x 256 to 192 x 256 |

| Base FOV | 44 x 44 cm |

| NEX | 1 |

| Parallel imaging accelerating factor | None |

| Bandwidth | ± 1,480 Hz/Px |

Notes: TE = time to echo; TR = repetition time, FOV = field of view; NEX = number of excitations

Notes: GRE = gradient-recalled echo; MRI-M = magnitude-based magnetic resonance imaging; TE = time to echo; TR = repetition time; FOV = field of view; NEX = number of excitations; Hz = Hertz; Px = pixel

Recent studies have suggested that DWI parameter estimation may be confounded by hepatic fat [27], so a two-dimensional, multi-echo, magnitude-based, spoiled gradient-recalled echo sequence was also obtained to estimate proton density fat fraction (PDFF), a biomarker for hepatic fat content [28, 29] (see Table 1b).

Image Reconstruction

Image reconstruction was performed using a recently-described method based on the Beta*LogNormal (BLN) distribution [30]. The BLN method reduces bias from bulk motion in liver DWI [30] by modeling it separately from variance, effectively weighting artifact-free images more heavily. Thus, it improves on conventional magnitude averaging, which assigns equal weight to all images regardless of the presence of motion-induced phase errors. Therefore, while conventional magnitude averaging corrects phase shift errors that occur between single excitations, the BLN method also addresses phase dispersion errors that occur within single excitations [31].

Parametric Maps

Three quantitative parameters were calculated from reconstructed images: apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), diffusivity (D), and perfusion fraction (F). ADC is a composite parameter reflecting incoherent molecular motion within tissue. A mono-exponential model was used to calculate ADC as a least-squares fit over all three b-values. D and F were derived from the intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) model [32]. Under the IVIM model, motion is separated into two ‘compartments’, each with its own separate diffusion coefficient: ‘true’ diffusion (D); and ‘micro-circulatory’ perfusion, also known as pseudo-diffusion (D*). F represents the fraction of signal from the pseudo-diffusion compartment. IVIM signal attenuation was modeled bi-exponentially:

| (1) |

Where Sb is signal intensity at a given b-value. Since reproducibility of D* is poor [33] we chose to derive only D and F. Based on the assumption that the D* component is negligible at b = 100 mm2/s [34], D and F were directly calculated from the following equations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Thus, three DWI parameter maps were calculated (ADC, D, and F), the first using mono-exponential and the latter two using bi-exponential models of signal intensity versus b-value, as described previously by Murphy et al. [15].

Parameter maps of estimated PDFF were also generated. Briefly, signal intensity values from six consecutive nominally out-of-phase and in-phase echoes were fit through a previously validated non-linear fitting algorithm, which includes modeling for T2* decay, and spectral complexity of fat, to estimate PDFF [35]. This calculation was performed pixel by pixel for every slice of the acquisition.

Image Analysis

Parametric maps were transferred offline for further processing on one of our institution’s work stations using open-source image processing and viewing software (Osirix; Osirix Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland).

Regions-of-interest (ROIs) were placed on each slice of the reconstructed parametric map images, drawn to include the right lobe of the liver while avoiding kidney, gallbladder, major vessels and bile ducts, liver edges, and artifact. All ROIs were drawn by an image analyst with >2 years of experience (JH, reader 1). These ROIs were automatically propagated to the corresponding anatomic regions of the ADC, D, and F parametric maps. For each map, the weighted mean value over the ROIs was calculated and recorded.

To assess interobserver reproducibility of image analysis, a subset was randomly selected for independent reevaluation (20% of patients). This image analysis was performed by a radiology resident with > 2 years of research experience (PM, reader 2) in an identical manner as described above.

Additionally, circular 1-cm radius ROIs were placed on PDFF maps in each of the nine Couinaud liver segments. PDFF over all nine segments was averaged and recorded for each subject.

PDFF Adjustment

Because chemical shift-based fat suppression techniques were used for the DWI sequence, approximately 10% of lipid, corresponding to fat spectral peaks with chemical shift similar to water, may have remained unsuppressed. Lipid diffuses two orders of magnitude slower than water and can theoretically confound DWI parameter estimates [27]. To correct for this possibility, 10 % of the T2-weighted PDFF (T2PDFF) was subtracted from the signal intensity at each b-value and IVIM parameters were re-calculated using these corrected signal intensities. T2PDFF was derived from PDFF using the following equation:

| (4) |

Where T2w = 23 ms and T2f = 62 ms, as has been described previously [27]. Using the T2PDFF, the adjusted signal intensity was calculated as follows:

| (5) |

After adjustment of signal intensities at each b-value, D and F were re-calculated for each subject.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics were summarized descriptively. Associations between histologic features (steatosis, fibrosis, lobular inflammation, portal inflammation, and hepatocellular ballooning) and DWI parameters (ADC, D, and F) were examined using Spearman’s rank correlation. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare presence or absence of NASH by DWI parameter. Multivariable linear regression was performed to assess the effect of each histologic feature on each DWI parameter. The regression models used were:

| (6) |

| (7) |

Where P = DWI parameter (ADC, D, or, F), STE= steatosis score, FIB = fibrosis score, LINF = lobular inflammation score, PINF = portal inflammation score, BAL = hepatocellular ballooning score, and NASH = NASH score (presence or absence of NASH). In model 2, regression was performed to assess effect of NASH on each DWI parameter, controlling for potential confounding factors fibrosis and steatosis.

To evaluate effects after adjustment for PDFF, paired t-tests were used to compare D and F parameters pre- and post-adjustment. Correlations and multivariable analyses were repeated as described above to evaluate post-adjustment correlations between histologic features and D and F parameters with significance level set to 0.05.

For the subset of reevaluated patients, interobserver reproducibility between reader 1 and reader 2 was assessed using the Bland-Altman method. Mean absolute differences, limits of agreement, and intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated. To determine whether any systematic bias between readers existed, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed.

The R software package was used for all statistical analysis (R Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Population Characteristics

Sixty-four children aged 8 – 17 yrs at time of biopsy were evaluated. Summaries of demographics, distribution of histologic features, and values for DWI parameters are provided in Table 2. All but two children had steatosis (62/64, 97%). Over half of children had NASH (34/64, 53%), and four children (4/64, 6%) had advanced (stage 3–4) fibrosis, including one child (1/64, 2%) with cirrhosis.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics, and distribution of histologic features and DWI parameters

| Descriptive Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Information | |||||

| Subjects (total number) | 64 | ||||

| Age (yrs) | Mean ± SD: 12 ± 2, Range: 8 – 17 | ||||

| Gender (numbers) | M: 19, F: 45 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | Mean ± SD: 30 ± 6, Range: 21 – 46 | ||||

| Histologic Feature | Number of Subjects with Each Score | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Steatosis | 2 | 18 | 17 | 27 | - |

| Fibrosis | 44 | 12 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Lobular Inflammation | 1 | 21 | 40 | 2 | - |

| Portal Inflammation | 30 | 32 | 2 | - | - |

| Hepatocellular Ballooning | 32 | 28 | 4 | - | - |

| Diagnosis of NASH | Present | Absent | |||

| NASH (number subjects) | 30 | 34 | |||

| DWI Parameter | Mean (Range) | ||||

| ADC (10−3 mm2/s) | 1.3 (0.94 – 1.8) | ||||

| D (10−3 mm2/s) | 0.82 (0.56 – 1.0) | ||||

| F (%) | 17 (6.0 – 28) | ||||

Notes: BMI = body mass index. Demographic information and histologic score distribution are reported. Histologic scores are based on the NASH CRN criteria. For each DWI parameter, mean and range is reported.

Correlation of Histologic Features and DWI Parameters

Correlations between histologic features and DWI parameters showed the following significant relationships (p < 0.05): a) ADC decreased with steatosis; b) D decreased with steatosis; and c) F decreased with fibrosis (Figure 1). After adjusting for multivariable effects, all the correlations remained significant (p < 0.05) (Table 3). These associations are graphically depicted in Figures 2 and 3. No significant associations were found between portal inflammation, lobular inflammation, or hepatocellular ballooning and any DWI parameter by univariable or multivariable analyses.

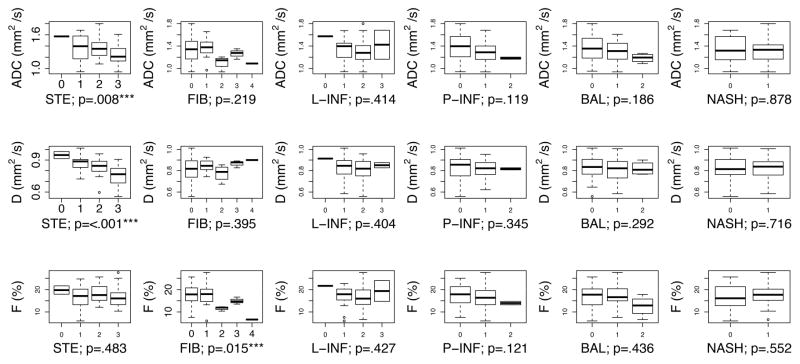

Figure 1.

Univariate associations between DWI parameters (ADC top, D middle, F bottom) and each histologic feature (STE: steatosis, FIB: fibrosis, L-INF: lobular inflammation, P-INF: portal inflammation, BAL: ballooning, and presence/absence of NASH) are shown. The boxplot indicates the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles, and the minimum and maximum value of each DWI parameter. Plots for ordinal variables are annotated with the p-value from the Spearman correlation test. Plots for the categorical variable NASH (presence/absence of NASH) are annotated with the p-value from the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regression tables

| Regression | DWI-Derived Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Coefficient | ADC [95% CI] (10−3 mm2/s) | D [95% CI] (10−3 mm2/s) | F [95% CI] (%) |

| 1 | Steatosis |

−0.08 [−0.13, −0.02] p=0.007 |

−0.06 [−0.08, −0.03] p<0.001 |

−0.36 [−1.64, 0.92] p=0.57 |

| Fibrosis | −0.05 [−0.11, 0.01] p=0.12 |

0.01 [−0.01, 0.04] p=0.34 |

−1.84 [−3.21, −0.46] p=0.010 |

|

| Lobular Inflammation | 0.07 [−0.04, 0.18] p=0.20 |

0.01 [−0.04, 0.05] p=0.84 |

1.51 [−0.93, 3.96] p=0.22 |

|

| Portal Inflammation | −0.06 [−0.17, 0.05] p=0.27 |

−0.01 [−0.06, 0.04] p=0.76 |

−0.98 [−3.41, 1.45] p=0.42 |

|

| Hepatocellular Ballooning | −0.04, [−0.13, 0.04] p=0.29 |

−0.02 [−0.05, 0.02] p=0.38 |

−0.50 [−2.36, 1.36] p=0.59 |

|

| 2 | Steatosis | −0.08 [−0.14, −0.03] p=0.004 |

−0.06 [−0.09, −0.04] p<0.001 |

−0.51 [−1.72, 0.70] p=0.40 |

| Fibrosis | −0.06 [−0.12, −0.01] p=0.06 |

0.01 [−0.02, 0.03] p=0.45 |

−2.14 [−3.35, −0.92] p<0.001 |

|

| NASH | 0.05 [−0.05, 0.16] p=0.30 |

0.01 [−0.04, 0.05] p=0.81 |

2.11 [−0.18, 4.40] p=0.07 |

|

Notes: Results of multivariate linear regression shown. The coefficient and significance of the effect is shown for each histologic feature of NAFLD. Coefficients with p < 0.05 are bolded for visibility.

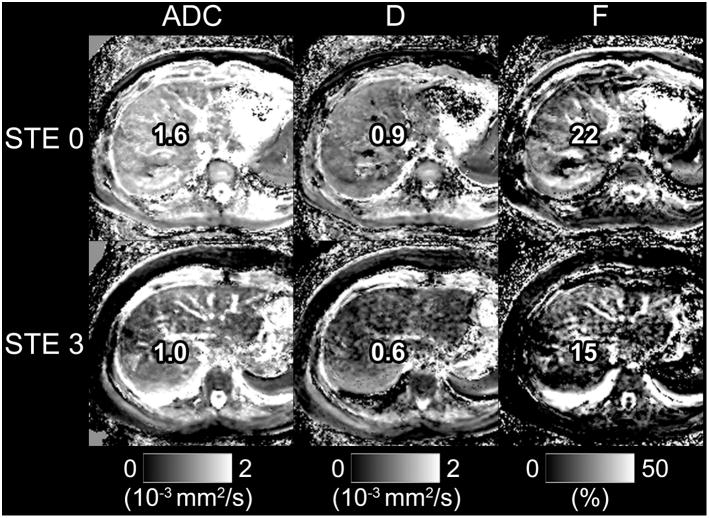

Figure 2.

Parametric maps of ADC, D, and F are shown for a subject with steatosis = 0, fibrosis = 0 (top) and a subject with steatosis = 3, fibrosis = 0 (bottom). Note reduced signal intensity in the liver parenchyma for maps of ADC and D in the subject with elevated steatosis.

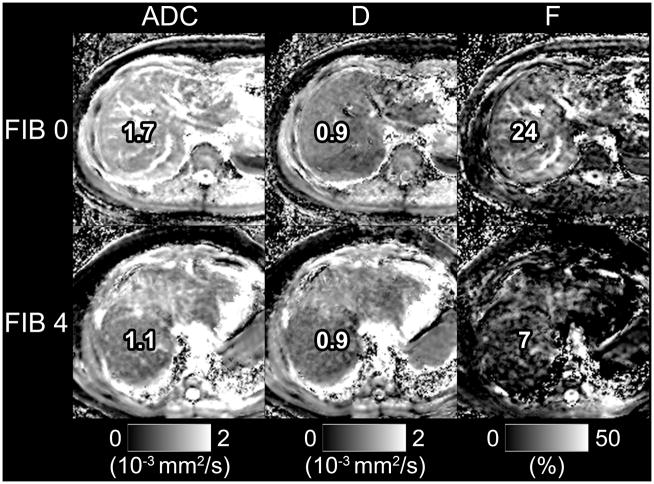

Figure 3.

Parametric maps of ADC, D, and F are shown for a subject with fibrosis = 0 steatosis = 1 (top) and a subject with fibrosis = 4, steatosis = 1 (bottom). Note reduced signal intensity in the liver parenchyma for the F map in the subject with elevated fibrosis. In this example, signal intensity is also reduced in the ADC map, likely because ADC is a composite parameter which encompasses both diffusion and perfusion effects. In this extreme example of fibrosis, the change in perfusion likely affects ADC as well.

Comparing children with NASH to those without NASH, no statistically significant difference was found for any DWI parameter using univariable or multivariable analyses.

PDFF Adjustment

After adjustment for PDFF, small but statistically significant changes were seen between pre-adjusted D and F and post-adjusted D and F (p < 0.001) (Table 4). All post-adjustment values were slightly higher. However, the same associations between histologic features and D and F remained statistically significant before and after PDFF adjustment (Figure 4, Table 5).

Table 4.

Distribution of PDFF and, after adjustment for PDFF, of IVIM parameters

| Post-adjustment Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hepatic Steatosis Parameter | Mean (Range) | |

| PDFF (%) | 18 (1 – 40)% | |

| DWI Parameter | Mean (Range) | p-value |

| D (10−3 mm2/s) | 0.84 (0.57 – 1.0) | < 0.001 |

| F (%) | 17 (6 – 27) | < 0.001 |

Notes: Mean and range for PDFF and IVIM parameters (D and F) reported. P-value refers to paired student’s t-test of pre-adjusted parameter vs. post-adjusted parameter.

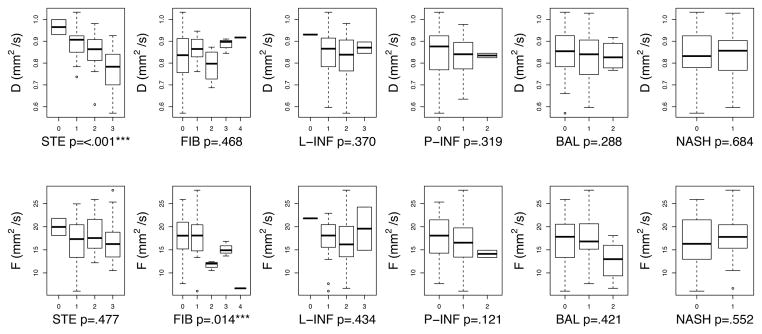

Figure 4.

Univariable associations between IVIM DWI parameters (D top, F bottom) and each histologic feature (STE: steatosis, FIB: fibrosis, L-INF: lobular inflammation, P-INF: portal inflammation, BAL: ballooning, and presence/absence of NASH) are shown. The boxplot indicates the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles, and the minimum and maximum value of each DWI parameter. Plots for ordinal variables are annotated with the p-value from the Spearman correlation test. Plots for the categorical variable NASH (presence/absence of NASH) are annotated with the p-value from the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Table 5.

Multivariate linear regression tables after adjustment for PDFF

| Regression | DWI-derived Parameter | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Coefficient | ADC [95% CI] (10−3 mm2/s) | D [95% CI] (10−3 mm2/s) |

| 1 | Steatosis |

−0.06 [−0.09, −0.03] p<0.001 |

−0.36 [−1.66, 0.94] p = 0.58 |

| Fibrosis | 0.01 [−0.02, 0.04] p = 0.37 |

−1.87 [−3.26, −0.47], p = 0.009 |

|

| Lobular Inflammation | 0.01 [−0.04, 0.06], p = 0.82 |

1.54 [−0.94, 4.01] p = 0.22 |

|

| Portal Inflammation | −0.01 [−0.06, 0.04] p = 0.73 |

−1.00 [−3.46, 1.46] p = 0.42 |

|

| Hepatocellular Ballooning | −0.02 [−0.06, 0.02] p = 0.37 |

−0.51 [−2.39, 1.37] p = 0.59 |

|

| 2 | Steatosis | −0.06 [−0.09, −0.04] p < 0.001 |

−0.51 [−1.73, 0.72] p = 0.41 |

| Fibrosis | 0.01 [−0.02, 0.03] p = 0.50 |

−2.17 [−3.40, −0.94] p < 0.001 |

|

| NASH | 0.01 [−0.04, 0.05] p = 0.81 |

2.13 [−0.19, 4.46] p=0.07 |

|

Results of multivariate linear regression post-adjustment for PDFF is shown. The coefficient and significance of the effect is shown for each histologic feature of NAFLD. Coefficients with p < 0.05 are bolded for visibility

Interobserver Reproducibility

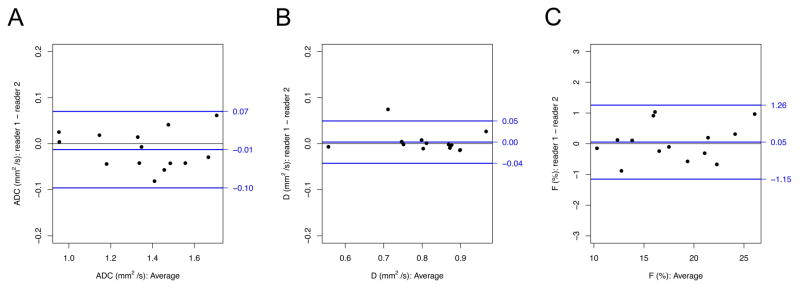

Interobserver reproducibility of ADC, D, and F was excellent with ICC’s 0.984, 0.992, and 0.976 respectively. No systematic bias between readers was identified with p > 0.05 for ADC, D, and F. (Figure 5, Table 6)

Figure 5.

Bland-Altman analyses of interobserver reprodcibility. Difference in reader 1 and reader 2 (reader 1 – reader 2) is plotted as a function of mean reader 1 and reader 2 analyses for DWI-derived parameters a) ADC, b) D, c) and F. The blue line in the middle of each graph indicates the mean difference. The two blue lines above and below indicate the 95% limits of agreement.

Table 6.

Interobserver reproducibility

| Interobserver Reproducibility | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DWI-Derived Parameter | Mean Difference | 95% LOA | ICC | p-value |

| ADC (10−3 mm2/s) | −0.013 | −0.096 − 0.070 | 0.984 | 0.241 |

| D (10−3 mm2/s) | 0.003 | −0.043 − 0.049 | 0.992 | 0.502 |

| F (%) | 0.052 | −1.154 − 1.258 | 0.976 | 0.808 |

Notes: Results of tests of interobserver reproducibility for subset of patients evaluated by reader 1 and reader 2. Mean differences (reader 1 minus reader 2) with 95% limits of agreement (LOA), ICC, and significance of Wilcoxon signed-rank test are provided. P-value refers to Wilcoxon signed-rank test comparing reader 1 to reader 2.

Discussion

Our results showed that in children with NAFLD, steatosis was associated with reduced D and ADC, and fibrosis was associated with reduced F. No significant association with any DWI parameter was found for lobular inflammation, portal inflammation, hepatocellular ballooning, or the presence/absence of NASH.

The reduction of D with steatosis observed in this study is in keeping with prior studies in adults where it was also shown that D decreased with steatosis [15–17]. A plausible but speculative explanation is that fat droplets impede the movement of water, and thus the accumulation of fat droplets within hepatocytes restricts intracellular water motion. Alternatively, Hansmann et al. [24] suggested that the reduction of D could be spurious and caused by unsuppressed lipid signal. While unsuppressed lipid signal may be contributory, it does not fully explain the reduction in D, since the relationship between steatosis and D remained significant after mathematically adjusting for PDFF in this pediatric study, and also in a prior study in adults [15].

The reduction of ADC with steatosis observed in this study has been observed inconsistently in prior research in adults and in animal models of NAFLD. One study in adults [18] and another in mice [19] found that ADC decreased with steatosis. Other studies in adults with NAFLD, however, demonstrated no significant relationship [15, 16, 36]. The inconsistent relationship reported between ADC and steatosis is not understood. One plausible explanation is that ADC is a composite parameter that incorporates the effects of both D and D* [32]; since acquisition parameters determine whether ADC is weighted towards D or D* [37] the selection of acquisition parameters may affect whether associations are observed. This explanation is not fully satisfactory, however, since no association was found between ADC and steatosis in a recent study of adult NAFLD where almost identical scan parameters were used [15]. Further research is needed to understand the relationship between ADC and steatosis.

Our results parallel previous studies of NAFLD in rabbits [20] and adults [15], where fibrosis correlated with F but not ADC in multivariable regression analyses. The correlation between fibrosis and F may reflect compression of hepatic sinusoids by deposition of collagen and other macromolecules in the perisinusoidal space. Fibrosis does not appear to affect true diffusion; therefore, depending on the degree to which the ADC is weighted toward D, associations between ADC and fibrosis may or may not be observed. Our results in NAFLD are discrepant from those previously reported in chronic hepatitis C infection, where ADC consistently was found to correlate inversely with fibrosis [9–14]. Further research will be needed to determine whether this discrepancy is due to microstructural differences between NAFLD and chronic hepatitis C infection, differences in technique, or other factors.

No association between portal inflammation, lobular inflammation, hepatocellular ballooning, or NASH was observed for any DWI parameter. Thus, inflammatory changes associated with NAFLD in children may not restrict diffusion or reduce perfusion as assessed by current DWI technology. Our results are concordant with prior studies in which multivariable regression analyses were performed, including a study in adults with NAFLD [15], and in a rabbit model of NAFLD [20]. In these studies, inflammation had no significant independent effects on DWI parameters. In contrast, several studies have reported significant univariable relationships between inflammation and ADC, including one study in adults with HCV infection [12], one study in children with HCV infection [13], and in a murine model of NAFLD [19]. Since multivariable regression analysis was not performed in those studies, the observed relationships may have reflected underlying fibrosis or factors other than inflammation.

For the subset of patients evaluated for interobserver reproducibility, our results showed excellent agreement. Previous studies have shown that imaging parameters and anatomic location largely influence reproducibility [38–40]. For this reason imaging in this study was performed free breathing, using multiple excitations, with all measurements taken in the right hepatic lobe. Our results are in keeping with a prior study evaluating interobserver reproducibility of ADC performed free breathing in the right hepatic lobe of healthy subjects. In that study, ICC was also found to be excellent [38]. However, to our knowledge intra- and interobserver reproducibility of IVIM parameters D and F has not yet been systematically evaluated in the liver of patients with NAFLD.

Currently a number of non-invasive tools are available for evaluation of hepatic steatosis (MR multi-echo imaging / MR spectroscopy) and fibrosis (ultrasound and MR elastography). Hence, DWI in its current state is unlikely to detect and quantify steatosis and fibrosis in children more accurately than other imaging techniques. However, as shown in this study, DWI is sensitive to the microstructural environment of tissue. In future studies, quantitative DWI parameters could be used as biological probes to gain insight into the pathophysiology of NAFLD as well as its treatment.

This study has several limitations. First, images were acquired using only three b-values, prohibiting estimation of D*, but allowing mitigation of bulk motion artifact on ADC, D, and F. Given the low reproducibility of D* [32] this parameter offers limited value. Therefore we prioritized artifact mitigation by repeated acquisition of just three b-values in the available scan time. A previous study of IVIM parameter estimation in the liver suggested that using fewer b-values did not substantially degrade repeatability and reproducibility [41], but the issues of reproducibility and repeatability were not formally evaluated in our present study.

Second, a single observer performed the majority of image analysis. Based on subset analyses of interobserver reproducibility, variability between observers for image analysis was minimal and no systematic bias was observed. Third, imaging was performed during free breathing without respiratory or cardiac gating. To mitigate potential bulk motion artifact, reconstruction was performed using the BLN method which has been shown to reduce variance and bias from bulk motion in liver DWI.

Fourth, the study population was relatively small and only a small proportion of children had severe fibrosis (4/64 = 6%) or severe degrees of portal or lobular inflammation; additional associations may have been observed if the study included more children with advanced fibrosis or inflammation. However, as recruitment was prospective and consecutive, our study cohort was representative of the population of children with known or suspected NAFLD in whom a pediatric hepatologist may obtain a liver biopsy for clinical care. Thus, the cohort is an appropriate one in which to assess histological correlates of DWI parameters.

In conclusion, in children with NAFLD, steatosis was associated with reduction in hepatic water diffusion, while fibrosis was associated with reduction in hepatic perfusion. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying these associations and possibly to apply these DWI parameters to gain insight into the pathophysiology of NAFLD.

Acknowledgments

Yesenia Covarrubias

Grant Support:

The project described was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health, Grants R56DK090350, U01DK061730, U01DK061734, T32EB005970, and TL1TR00098. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, Lavine JE, Stanley C, Behling C. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):1388–1393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunt EM. Pathology of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2005;33(2):68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dezsőfi A, Knisely AS. Liver biopsy in children 2014: Who, whom, what, when, where, why? Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology. 2014;38(4):395–398. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis S, Dyvorne H, Cui Y, Taouli B. Diffusion-Weighted Imaging of the Liver: Techniques and Applications. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Clinics of North America. 2014;22(3):373–395. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taouli B, Koh DM. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the liver. Radiology. 2010;254(1):47–66. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh DM, Collins DJ, Orton MR. Intravoxel incoherent motion in body diffusion-weighted MRI: reality and challenges. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(6):1351–61. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicholson C, Phillips JM. Ion diffusion modified by tortuosity and volume fraction in the extracellular microenvironment of the rat cerebellum. J Physiol. 1981;321:225–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szafer A, Zhong J, Anderson AW, Gore JC. Diffusion-weighted imaging in tissues: theoretical models. NMR Biomed. 1995;8(7–8):289–96. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940080704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Girometti R, Furlan A, Bazzocchi M, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI in evaluating liver fibrosis: a feasibility study in cirrhotic patients. Radiol Med. 2007;112(3):394–408. doi: 10.1007/s11547-007-0149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koinuma M, Ohashi I, Hanafusa K, Shibuya H. Apparent diffusion coefficient measurements with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of hepatic fibrosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;22(1):80–5. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewin M, Poujol-Robert A, Boelle PY, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):658–65. doi: 10.1002/hep.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taouli B, Chouli M, Martin AJ, Qayyum A, Coakley FV, Vilgrain V. Chronic hepatitis: role of diffusion-weighted imaging and diffusion tensor imaging for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis and inflammation. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(1):89–95. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Razek AA, Khashaba M, Abdalla A, Bayomy M, Barakat T. Apparent diffusion coefficient value of hepatic fibrosis and inflammation in children with chronic hepatitis. Radiol Med. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11547-014-0408-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Razek AAKA, Abdalla A, Omran E, Fathy A, Zalata K. Diagnosis and quantification of hepatic fibrosis in children with diffusion weighted MR imaging. European Journal of Radiology. 2011;78(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy P, Hooker J, Ang B, et al. Associations between histologic features of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and quantitative diffusion-weighted MRI measurements in adults. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jmri.24755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leitao HS, Doblas S, d’Assignies G, et al. Fat deposition decreases diffusion parameters at MRI: a study in phantoms and patients with liver steatosis. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(2):461–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2626-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guiu B, Petit JM, Capitan V, et al. Intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a 3.0-T MR study. Radiology. 2012;265(1):96–103. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poyraz AK, Onur MR, Kocakoc E, Ogur E. Diffusion-weighted MRI of fatty liver. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(5):1108–11. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson SW, Soto JA, Milch HN, et al. Effect of disease progression on liver apparent diffusion coefficient values in a murine model of NASH at 11.7 Tesla MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33(4):882–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joo I, Lee JM, Yoon JH, Jang JJ, Han JK, Choi BI. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: intravoxel incoherent motion diffusion-weighted MR imaging-an experimental study in a rabbit model. Radiology. 2014;270(1):131–40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Newbury R, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;42(3):641–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.20842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Awai HI, Newton KP, Sirlin CB, Behling C, Schwimmer JB. Evidence and Recommendations for Imaging Liver Fat in Children, Based on Systematic Review. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;12(5):765–773. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou MABFKJ, editor. Handbook of MRI Pulse Sequences. Academic Press; Burlington: 2004. Introduction; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loomba R, Sirlin CB, Ang B, et al. Ezetimibe for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Assessment by novel MRI and MRE in a randomized trial (MOZART Trial) Hepatology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hep.27647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwimmer JB, Newton KP, Awai HI, et al. Paediatric gastroenterology evaluation of overweight and obese children referred from primary care for suspected non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(10):1267–77. doi: 10.1111/apt.12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwimmer JB, Zepeda A, Newton KP, et al. Longitudinal assessment of high blood pressure in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansmann J, Hernando D, Reeder SB. Fat confounds the observed apparent diffusion coefficient in patients with hepatic steatosis. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(2):545–52. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noureddin M, Lam J, Peterson MR, et al. Utility of magnetic resonance imaging versus histology for quantifying changes in liver fat in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease trials. Hepatology. 2013;58(6):1930–40. doi: 10.1002/hep.26455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang A, Tan J, Sun M, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: MR imaging of liver proton density fat fraction to assess hepatic steatosis. Radiology. 2013;267(2):422–31. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy P, Wolfson T, Gamst A, Sirlin C, Bydder M. Error model for reduction of cardiac and respiratory motion effects in quantitative liver DW-MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(5):1460–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou MABFKJ, editor. Handbook of MRI Pulse Sequences. Academic Press; Burlington: 2004. Chapter 13 - Common Image Reconstruction Techniques; pp. 491–571. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Aubin ML, Vignaud J, Laval-Jeantet M. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;168(2):497–505. doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.2.3393671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kakite S, Dyvorne H, Besa C, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Short-term reproducibility of apparent diffusion coefficient and intravoxel incoherent motion parameters at 3.0T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jmri.24538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JT, Liau J, Murphy P, Schroeder ME, Sirlin CB, Bydder M. Cross-sectional investigation of correlation between hepatic steatosis and IVIM perfusion on MR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(4):572–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bydder M, Yokoo T, Hamilton G, et al. Relaxation effects in the quantification of fat using gradient echo imaging. Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;26(3):347–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.d’Assignies G, Ruel M, Khiat A, et al. Noninvasive quantitation of human liver steatosis using magnetic resonance and bioassay methods. Eur Radiol. 2009;19(8):2033–40. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guiu B, Cercueil JP. Liver diffusion-weighted MR imaging: the tower of Babel? Eur Radiol. 2011;21(3):463–7. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-2017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen X, Qin L, Pan D, et al. Liver Diffusion-weighted MR Imaging: Reproducibility Comparison of ADC Measurements Obtained with Multiple Breath-hold, Free-breathing, Respiratory-triggered, and Navigator-triggered Techniques. Radiology. 2014;271(1):113–125. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SY, Lee SS, Byun JH, et al. Malignant Hepatic Tumors: Short-term Reproducibility of Apparent Diffusion Coefficients with Breath-hold and Respiratory-triggered Diffusion-weighted MR Imaging. Radiology. 2010;255(3):815–823. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwee TC, Takahara T, Koh DM, Nievelstein RA, Luijten PR. Comparison and reproducibility of ADC measurements in breathhold, respiratory triggered, and free-breathing diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the liver. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(5):1141–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dyvorne H, Jajamovich G, Kakite S, Kuehn B, Taouli B. Intravoxel Incoherent Motion Diffusion Imaging of the Liver: Optimal b-value Subsampling and Impact on Parameter Precision and Reproducibility. European journal of radiology. 2014;83(12):2109–2113. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]