Abstract

Background

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) from human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matched related donors (RD) and matched unrelated donors (URD) produce similar outcomes in patients with acute myelogenous leukemia, while donor source has been reported as a predictor of outcomes in myelodysplastic syndrome.

Methods

Post-HCT outcomes in 1458 ALL patients from 2000-2011 were analyzed, comparing RD versus URD transplants.

Results

Median age was 37 years (range, 18-69). In multivariate analysis, HLA 8/8 allele matched URD recipients had similar transplant-related mortality (TRM) and all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 1.16 [95% CI 0.91-1.48] and HR 1.01 [95% CI 0.85-1.19], respectively) compared to RD recipients; 7/8 URD had greater risk of TRM and all-cause mortality compared to RD (HR 1.92 [95% CI 1.47-2.52] and HR 1.29 [95% CI 1.05-1.58], respectively). Risk of TRM and all-cause mortality was also greater comparing 7/8 to 8/8 URD. Compared to RD, both 8/8 and 7/8 URD had lower risk of relapse (HR 0.77 [95% CI 0.62-0.97] and HR 0.75 [95% CI 0.56-1.00], respectively). Both 8/8 and 7/8 URD had greater risk of acute GVHD (HR 2.18 [95% CI 1.76-2.70] and HR 2.65 [95% CI 2.06-3.42], respectively) and chronic GVHD (HR 1.28 [95% CI 1.06-1.55] and HR 1.46 [95% CI 1.14-1.88], respectively) compared to RD.

Conclusions

In the absence of RD, 8/8 URD is a viable alternative with similar survival outcomes, while 7/8 URD transplantation is associated with poorer overall survival.

Keywords: stem cell transplantation, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), human leukocyte antigen (HLA) match, allogeneic transplantation, related donors, unrelated donors

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is a potentially life-saving treatment for patients suffering from acute leukemia, lymphoma, and other hematologic diseases. Siblings with matching human leukocyte antigen (HLA) are the preferred donor source, but only about one-third of patients have an HLA matched related donor (RD). If a RD is not available, a matched unrelated donor (URD) is sought. Depending on the recipient's race and ethnicity, the likelihood of finding a fully HLA-allele matched (HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1 [8/8]) URD ranges from 16-75%, and 66-97% for a 7/8 HLA match.1-5 HCT from a URD has been associated historically with higher incidence of graft failure, more graft versus host disease (GVHD), and lower survival than RD transplants.6 However, more recent data have shown that survival rates for URD HCT have improved significantly, with two-year survival rates for URD recipients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) rising from 23% in 1987-1998, to 40% in 2003-2006.1,7

A recent analysis comparing the outcomes after RD transplant versus 8/8 URD versus 7/8 URD HCT for acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) patients demonstrated that 8/8 URD HCT recipients had similar survival rates as RD HCT recipients, while 7/8 URD recipients had higher early mortality, suggesting that contemporary use of URD and RD HCT produce similar survival outcomes in AML.8 A subsequent study examined the same question among patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), but unlike the findings in AML, donor source was an important predictor of outcomes.9 Recipients of 7/8 URD HCT had worse 3-year survival compared to RD and 8/8 URD groups.9 While AML patients had lower relapse risks in 7/8 URD vs. RD recipients (HR 0.78 [95% CI 0.63-0.98]),8 this relationship was not seen in MDS (HR 1.02 [95% CI 0.66-1.60]),9 indicating there may exist a disease-specific component to the GVL effect. Evaluating the role of donor source in determining outcomes of HCT for specific diseases might clarify the potency of the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect. We investigated the outcomes of RD versus 8/8 URD versus 7/8 URD HCT for patients with ALL. Furthermore, we sought to evaluate whether donor source impact on outcomes differs by conditioning regimen intensity, given that patients undergoing RIC HCT rely more on the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect of their transplant to prevent disease relapse.10

Methods

Data Source

The CIBMTR is a combined research program of the Medical College of Wisconsin and the National Marrow Donor Program. The CIBMTR comprises a voluntary network of more than 450 transplantation centers worldwide that contribute detailed data on consecutive allogeneic and autologous HCT to a centralized statistical center. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed in compliance with all applicable federal regulations pertaining to the protection of human research participants. Protected health information used in the performance of such research is collected and maintained in the CIBMTR capacity as a public health authority under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule. Additional details regarding the data source are described elsewhere.11

Patient Selection

The patient population consisted of adult patients (≥18 years) with B-lineage ALL undergoing their first allogeneic HCT in the United States between 2000-2011 who had comprehensive data reported to the CIBMTR. A total of 1458 cases fulfilling the inclusion criteria were identified. Of these, 440 received RD transplants from matched siblings, 729 received 8/8 HLA-matched URD transplants, and 289 received 7/8 HLA-matched URD transplants. Patients receiving umbilical cord blood transplantation and patients receiving stem cells from identical twins, HLA-mismatched, haploidentical, or nonsibling-related donors were excluded. Patients whose disease status at transplant was missing were excluded, and pre-HCT presence or absence of minimal residual disease was not assessed. Patients whose grafts were depleted of T-cells ex vivo or underwent CD34 cell selection were excluded. Patients receiving post-HCT cyclophosphamide for graft-vs-host disease prophylaxis were also excluded. The population was limited to patients with B-cell lineage disease only.

Study end points and definitions

The primary outcome studied was survival. Patients were considered to have an event at time of death from any cause; survivors were censored at time of last contact. Leukemia-free survival (LFS) was defined as time from transplant to treatment failure (death or relapse). Relapse was defined as leukemia recurrence defined by hematologic criteria as reported by the centers to the CIBMTR, and transplant-related mortality (TRM) was considered a competing event. TRM was defined as death in remission, and relapse was considered a competing event. Acute graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) was graded according to Consensus criteria.12 Chronic GVHD was diagnosed by standard criteria.13 For cumulative incidence of GVHD, death without GVHD was considered a competing event.

Statistical analysis

Overall survival and LFS estimates for RD, 8/8 URD and 7/8 URD recipients were calculated based on Kaplan-Meier estimates, and the 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the variance derived from Greenwood's formula. Cumulative incidence for TRM for the three groups was calculated using disease relapse as the competing risk, and cumulative incidence for relapse was calculated using TRM as the competing risk. Similarly, death was a competing risk for the cumulative incidence of acute and chronic GVHD.14 Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous covariates and Fisher's exact test for proportions were used to compare patient, disease, and transplant-related characteristics between groups. Log-rank tests were used to compare OS and LFS between RD, 8/8 URD and 7/8 URD. Similarly, unadjusted comparison between the three groups of patients in terms of treatment related mortality and relapse was performed via Gray's test for cumulative incidence curves. All P values were two-sided.

The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to compare 8/8 URD versus 7/8 URD versus RD in terms of overall survival, LFS, TRM, relapse, aGVHD, and cGVHD after adjusting for other risk factors. Patient-related (age at diagnosis, sex, Karnofsky performance score, race), disease-related (white blood cell count at diagnosis, cytogenetics, tyrosine kinase inhibitor usage at any time pre-transplant, disease status at transplant, time to achieve first complete remission (CR1) for patients transplanted in CR1, and duration of CR1 for patients transplanted in second complete remission), and transplant-related variables (donor age, donor-recipient sex matching, recipient CMV status, conditioning regimen intensity, graft source, year of HCT, GVHD prophylaxis regimen, and use of antithymocyte globulin) were included in the multivariate analyses using the Cox proportional hazards regression with a stepwise variable selection technique; P ≤ .05 was the criterion for inclusion in final models. Optimal cut points for continuous covariates were determined by maximizing the overall mortality hazard ratio. The main factor being tested in this study was the effect of donor source (8/8 URD versus 7/8 URD versus RD) on clinical endpoints; therefore this variable was included in all models. The proportional hazards assumption was examined for each variable, and if violated, variables were included as time-dependent covariates. The interaction between the main effect and significant covariates was tested; no significant interactions were found. Multivariate analysis was also performed after restricting the study population to patients transplanted in CR1 and CR2, or CR1 alone.

Results

Patients

Baseline patient population characteristics of patients with B-cell ALL are summarized in Table 1. Median follow-up times were 47, 61, and 71 months for RD, 8/8 URD and 7/8 URD, respectively. URD group patients were younger than RD patients. Median age (range) for the entire cohort was 37 years (18-69 years). Karnofsky Performance Scores were similar among all three groups. Across the three groups, patients were most commonly Caucasian, with the 8/8 URD group having a higher proportion of white patients. WBC count at diagnosis was similar across all three groups. Among patients with Philadelphia chromosome ALL, the RD group had a greater percentage receiving a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) as part of treatment. RD recipients were more likely transplanted in first complete remission (CR1), in comparison to the URD groups, which had a relatively higher percentage transplanted in second complete remission (CR2). The time from diagnosis to achieving CR1 for all patients who achieved CR1, as well as the duration of CR1 for patients transplanted in CR2 were similar across all groups. Conditioning regimen intensity and GVHD prophylaxis regimens were similar across all three groups. Use of in vivo T-cell depletion (antithymocyte globulin (ATG) and/or alemtuzumab) was more common in the URD groups. RD recipients received their transplants more recently than the URD groups, and were more likely to have received peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 1458 ALL patients undergoing allogeneic HCT from 2000-2011 and reported to the CIBMTR.

| Variable | RD | 8/8 URD | 7/8 URD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 440 | 729 | 289 | |

| Median age (range) | 41 (18-69) | 36 (18-68) | 34 (18-68) | 0.0012 * |

| Recipient Age (years) | 0.0224 † | |||

| ≤52 | 363 (83) | 585 (80) | 253 (88) | |

| > 52 | 77 (17) | 144 (20) | 36 (12) | |

| Sex | 0.1562 † | |||

| Male | 256 (58) | 431 (59) | 152 (53) | |

| Female | 184 (42) | 298 (41) | 137 (47) | |

| Karnofsky Performance Score | 0.5102 † | |||

| ≥ 90 | 268 (61) | 435 (60) | 187 (65) | |

| < 90 | 150 (34) | 245 (34) | 89 (31) | |

| Missing | 22 (5) | 49 (6) | 13 (4) | |

| Race | <.0001 ‡ | |||

| Caucasian | 355 (81) | 664 (91) | 242 (84) | |

| African American | 26 (6) | 18 (3) | 22 (8) | |

| Asian | 15 (3) | 15 (2) | 6 (2) | |

| Pacific Islander | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| Native American | 0 | 5 (1) | 2 (<1) | |

| Other | 42 (10) | 26 (4) | 17 (6) | |

| WBC count at diagnosis | 0.1621 † | |||

| < 30 x 10(&005E) 9/mm3 | 275 (63) | 431 (59) | 171 (59) | |

| > 30 x 10(&005E)9/mm3 | 102 (23) | 207 (28) | 68 (24) | |

| Missing | 63 (14) | 91 (12) | 50 (17) | |

| Cytogenetics □ | <.0001 † | |||

| Diploid | 163 (37) | 218 (30) | 89 (31) | |

| Intermediate (1-2 abnormalities) | 52 (12) | 77 (11) | 25 (9) | |

| Poor, Ph+, TKI used | 97 (22) | 58 (8) | 33 (11) | |

| Poor, Ph+, TKI not used | 49 (11) | 153 (21) | 52 (18) | |

| Poor, Ph+, TKI unknown | 2 (<1) | 21 (3) | 4 (1) | |

| Poor, Ph- | 56 (13) | 105 (14) | 45 (16) | |

| Missing | 21 (5) | 97 (13) | 41 (14) | |

| Disease status at transplant | <.0001 ‡ | |||

| First Complete Remission (CR1) | 275 (62) | 353 (48) | 128 (44) | |

| CR2 | 69 (16) | 193 (26) | 72 (25) | |

| CR3+ | 10 (2) | 27 (4) | 23 (8) | |

| Never treated | 0 | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| PIF | 21 (5) | 45 (6) | 12 (4) | |

| First relapse | 47 (11) | 70 (10) | 34 (12) | |

| Second relapse | 16 (4) | 38 (5) | 19 (7) | |

| Third or greater relapse | 2 (<1) | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | |

| Time from diagnosis to CR1 | 0.6959 † | |||

| ≤ 4 weeks | 66 (15) | 119 (16) | 50 (17) | |

| > 4 weeks | 286 (65) | 500 (69) | 183 (63) | |

| Missing | 88 (20) | 110 (15) | 56 (19) | |

| Duration of CR1 for CR2 patients | 0.1985 † | |||

| ≤ 30 months | 34 (8) | 104 (14) | 45 (16) | |

| > 30 months | 17 (4) | 60 (8) | 14 (5) | |

| Missing | 389 (88) | 565 (78) | 230 (79) | |

| Donor Age (years) | <.0001 † | |||

| < 33 | 138 (31) | 253 (35) | 73 (25) | |

| 33 – 50 | 177 (40) | 260 (36) | 117 (40) | |

| > 50 | 106 (24) | 33 (5) | 23 (8) | |

| Missing | 19 (4) | 183 (25) | 76 (26) | |

| Donor/Recipient sex match | <.0001 † | |||

| M/M | 145 (33) | 319 (44) | 95 (33) | |

| M/F | 111 (25) | 109 (15) | 57 (20) | |

| F/M | 95 (22) | 177 (24) | 75 (26) | |

| F/F | 89 (20) | 120 (17) | 59 (20) | |

| Missing | 0 | 4 (<1) | 3 (1) | |

| Recipient CMV status | <.0001 † | |||

| Positive | 226 (51) | 220 (30) | 93 (32) | |

| Negative | 191 (43) | 437 (60) | 156 (54) | |

| Missing | 23 (5) | 72 (10) | 40 (14) | |

| Conditioning regimen | 0.6514 † | |||

| Myeloablative + TBI | 346 (79) | 567 (78) | 227 (78) | |

| Myeloablative – TBI | 51 (12) | 79 (11) | 34 (12) | |

| Non-myeloablative/Reduced Intensity | 37 (8) | 82 (11) | 28 (10) | |

| Missing | 6 (1) | 1 (<1) | 0 | |

| GVHD prophylaxis | 0.1376 ‡ | |||

| FK506 +/- others | 309 (70) | 532 (73) | 210 (73) | |

| CSA +/- others | 119 (27) | 191 (26) | 76 (26) | |

| Other prophylaxis | 12 (3) | 6 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Antithymocyte Globulin/Alemtuzumab use | <.0001 † | |||

| Yes | 19 (4) | 144 (20) | 76 (26) | |

| No | 388 (88) | 568 (78) | 201 (70) | |

| Missing | 33 (8) | 17 (2) | 12 (4) | |

| Transplant year | <.0001 † | |||

| 2000-2003 | 83 (19) | 193 (26) | 88 (30) | |

| 2004-2007 | 174 (40) | 372 (51) | 138 (48) | |

| 2008-2011 | 183 (41) | 164 (23) | 63 (22) | |

| Graft type | <.0001 † | |||

| Bone marrow | 43 (10) | 238 (33) | 104 (36) | |

| Peripheral blood | 397 (90) | 491 (67) | 185 (64) | |

| Median follow-up, months (range) | 46 (12-140) | 61 (7-145) | 72 (8-145) |

Kruskal-Wallis test

Pearson's chi-square test

Fisher's exact test

Poor cytogenetics defined as Ph+/t(9;22), t(4;11), 11q23, MLL, hypodiploid, t(8;14), or ≥3 abnormalities

Multivariate Analysis

Survival

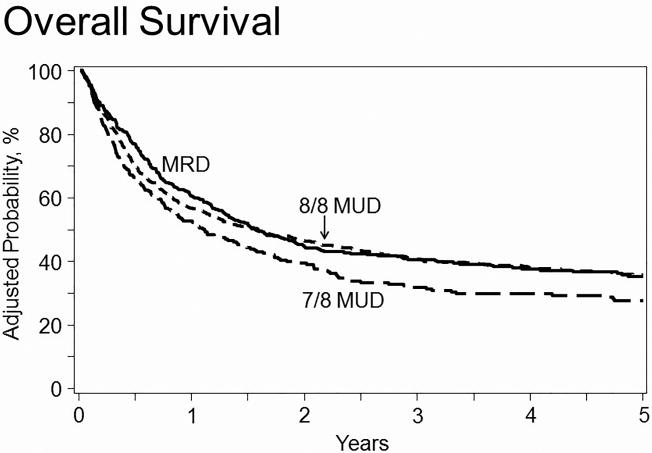

RD and 8/8 URD recipients (HR=1.01 [95% CI 0.85-1.19]) had the same risk of death from any cause, while 7/8 URD recipients had an increased risk of death (HR=1.29 [95% CI 1.05-1.58]) compared to RD recipients (Table 2). Covariates with adverse effects on overall survival included age>52, low KPS, non-white race, poor cytogenetic profile with Philadelphia chromosome negative, use of cyclosporine (CsA), patients transplanted in CR1 who took longer than 4 weeks to achieve CR, transplants in CR2 with short duration of CR1, and advanced disease status at transplant. The use of PBSC were also associated with higher risk of mortality, however this risk only became apparent at two years post-transplant. There was no significant difference in OS when comparing myeloablative conditioning +/- TBI and reduced intensity/non-myeloablative conditioning (Supplemental Table 1). The 5-year probability of overall survival, adjusted for other significant variables, was 35% (95% CI 30-40%), 36% (95% CI 32-40%), and 28% (95% CI 22-33%) for RD, 8/8 URD, and 7/8 URD recipients, respectively (Table 3; Figure 1).

Table 2. Multivariate analysis of acute and chronic GVHD, relapse, TRM, leukemia-free survival, and overall survival in adult ALL patients undergoing allogeneic HCT from 2000-2011.

| Acute GVHD | Chronic GVHD | Relapse | TRM | LFS | OS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

| 8/8 URD vs RD | 2.18 (1.76-2.70, p<0.0001) | 1.28 (1.06-1.55, p=0.01) | 0.77 (0.62-0.97, p=0.02) | 1.16 (0.91-1.48, p=0.23) | 0.95 (0.81-1.12, p=0.55) | 1.01 (0.85-1.19, p=0.93) |

| 7/8 URD vs RD | 2.65 (2.06-3.42, p<0.0001) | 1.46 (1.14-1.88, p=0.003) | 0.75 (0.56-1.00, p=0.05) | 1.92 (1.47-2.52, p<0.0001) | 1.20 (0.98-1.46, p=0.07) | 1.29 (1.05-1.58, p=0.01) |

| 7/8 URD vs 8/8 URD | 1.22 (1.00-1.48, p=0.05) | 1.14 (0.91-1.44, p=0.24) | 0.97 (0.74-1.28, p=0.84) | 1.66 (1.32-2.08, p<0.0001) | 1.26 (1.05-1.51, p=0.01) | 1.28 (1.07-1.53, p=0.008) |

Significant covariates in each of the final models: GVHD (use of ATG/alemtuzumab, donor/recipient sex matching, GVHD prophylaxis, graft type); Relapse (KPS, race, cytogenetics, conditioning regimen, disease status at transplant); TRM (age, KPS, race, GVHD prophylaxis, graft type, conditioning regimen); LFS (age, KPS, race, cytogenetics, GVHD prophylaxis, disease status at transplant, year of transplant); OS (age, KPS, race, cytogenetics, GVHD prophylaxis, disease status at transplant, graft type)

Table 3. Adjusted 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse and TRM, and adjusted 5-year probabilities of LFS and survival in adult ALL patients undergoing allogeneic HCT from 2000-2011.

| RD vs 8/8 URD | RD vs 7/8 URD | 8/8 vs 7/8 URD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Outcomes | RD Probability (95% CI) | 8/8 URD Probability (95% CI) | 7/8 URD Probability (95% CI) | P* | P† | P† | P† |

| Relapse | 43 (38-48) | 33 (29-37) | 31 (25-36) | .002 | .002 | .002 | .51 |

| TRM | 27 (22-31) | 32 (28-36) | 45 (38-52) | <0.001 | .10 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| LFS | 32 (27-36) | 34 (30-38) | 25 (20-30) | .025 | .46 | .06 | .007 |

| Survival | 35 (30-40) | 36 (32-40) | 28 (22-33) | .043 | .75 | .053 | .014 |

Overall point-wise comparison

Pair-wise point-wise comparison

Figure 1. Adjusted probability of overall survival in adult ALL patients by donor source.

In multivariate analysis, 7/8 URD recipients had significantly greater risk of mortality compared to RD and 8/8 URD recipients (HR 1.29, p=0.01 and HR 1.28, p=0.008, respectively), while there was no difference in risk comparing RD and 8/8 URD (HR 1.01, p=0.93).

Transplant-related mortality

There was no significant increased risk of TRM comparing 8/8 URD to RD recipients (HR=1.16 [95% CI 0.91-1.48]), while 7/8 URD recipients had an increased risk of TRM (HR=1.92 [95% CI 1.47-2.52]) (Table 2). Adverse covariates for TRM were recipient age>52, low KPS, non-white race, CsA use, and use of PBSC. PBSC use was only associated with higher rates of TRM starting at two years post-HCT. Reduced intensity/non-myeloablative conditioning regimens were associated with decreased risk of TRM. The 5-year cumulative incidence of TRM, adjusted for other significant variables, was 27% (95% CI 22-31%), 32% (95% CI 28-36%), and 45% (95% CI 38-52%) for RD, 8/8 URD, and 7/8 URD recipients, respectively (Table 3).

Relapse

Compared to RD recipients, 8/8 and 7/8 URD recipients had a decreased risk of relapse (HR=0.77 [95% CI 0.62-0.97] and HR=0.75 [95% CI 0.56-1.00], respectively) (Table 2). Adverse covariates for relapse included low KPS, non-white race, poor cytogenetic profile with Philadelphia chromosome negative, conditioning regimen lacking TBI, reduced intensity/non-myeloablative conditioning, transplants in CR2 with short CR1 duration, and advanced disease status at transplant. The adjusted 5-year cumulative incidence of relapse was 43% (95% CI 38-48%), 33% (95% CI 29-37%), and 31% (95% CI 25-36%) for RD, 8/8 URD and 7/8 URD recipients, respectively (Table 3).

Leukemia-free survival

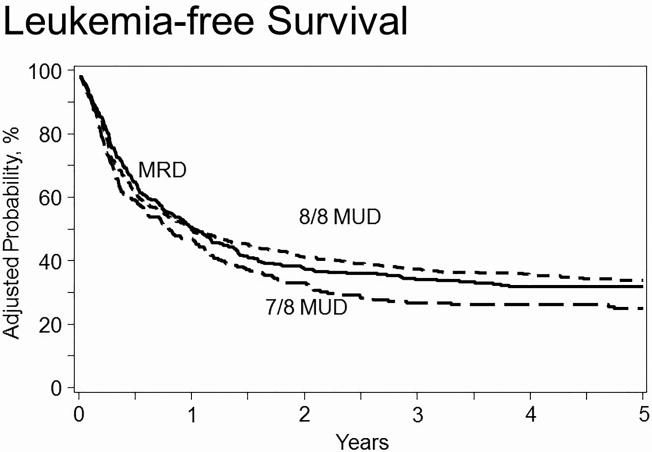

There was no increased risk of treatment failure, defined as death or relapse (the inverse of LFS), associated with 8/8 URD (HR=0.95 [95% CI 0.81-1.12]) or 7/8 URD (HR=1.20 [95% CI 0.98-1.46]) recipients, when compared with RD recipients (Table 2). Adverse covariates included age>52, low KPS, non-white race, poor cytogenetic profile with Philadelphia chromosome negative, CsA use, transplant in CR2 after a short CR1, advanced disease status at HCT, and transplants prior to 2004. There was no significant difference in LFS when comparing myeloablative conditioning +/- TBI and reduced intensity/non-myeloablative conditioning (Supplemental Table 1). The 5-year probability of LFS, adjusted for other significant variables, was 32% (95% CI 27-36%), 34% (95% CI 30-38%), and 25% (95% CI 20-30%) for RD, 8/8 URD and 7/8 URD recipients, respectively (Table 3; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Adjusted probability of leukemia-free survival in adult ALL patients by donor source.

In multivariate analysis, 8/8 URD and 7/8 URD recipients had no difference in risk of treatment failure compared to RD recipients (HR 0.95, p=0.55 and HR 1.20, p=0.07) respectively. 7/8 URD had greater risk than 8/8 URD (HR 1.26, p=0.01).

Graft-Versus-Host Disease

When compared to RD recipients, there was a greater risk of acute GVHD in 8/8 URD (HR=2.18 [95% CI 1.76-2.70]) and 7/8 URD (HR=2.65 [95% CI 2.06-3.42]) (Table 2). Other adverse covariates for acute GVHD were the lack of use of ATG/alemtuzumab, female recipient from male donor, use of CsA for GVHD prophylaxis, and use of PBSC. Compared to RD recipients, 8/8 URD (HR=1.28 [95% CI 1.06-1.55]) and 7/8 URD (HR=1.46 [95% CI 1.14-1.88]) recipients had increased risk of developing cGVHD (Table 2).

Cause of death

Table 4 summarizes the causes of death by donor source. The most common cause of death was primary disease (47%, 38%, and 26% for RD, 8/8 URD, and 7/8 URD, respectively).

Table 4. Causes of death in adult ALL patients undergoing allogeneic HCT from 2000-2011.

| Cause, n (%) | RD | 8/8 URD | 7/8 URD | p=0.0024 * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary disease | 117 (47) | 174 (38) | 56 (26) | |

| New malignancy | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 1 (<1) | |

| GVHD | 27 (11) | 59 (13) | 36 (17) | |

| Interstitial Pneumonitis | 15 (6) | 21 (5) | 17 (8) | |

| Infection | 43 (17) | 83 (18) | 33 (16) | |

| Organ failure | 28 (11) | 73 (16) | 42 (20) | |

| Other cause | 18 (7) | 46 (10) | 27 (13) |

Fisher's exact test

CR1 and CR2 Cohort Analyses

A subgroup analysis of outcomes restricted to patients receiving HCT while in first complete remission (n=756) was performed, yielding results largely similar to the results seen in the overall cohort (Supplemental Table 2). An additional subgroup analysis restricted to patients receiving HCT either in CR1 or CR2 was also performed, yielding the same results as the entire study population (data not shown).

Discussion

For adult patients with ALL, allogeneic HCT from a RD or URD has been shown to be a potentially curative, life-saving treatment.1-6 We suspected a possible relationship between relapse and TRM that is dependent on disease, due to the fact that each disease carries its own unique population of patients varying in median age, co-morbidities, ability to tolerate GVHD, and so forth. While a particular donor source may have high relapse rates and low TRM in one disease, these outcomes may differ in other diseases. We therefore evaluated the impact of donor source on allogeneic HCT outcomes in the setting of B-cell ALL.

Studies have looked at HCT outcomes among ALL patients as they relate to donor source and have shown similar outcomes for RD and URD transplants; however, their patient populations were limited in size.15,16 We focused on a larger, more recent cohort of ALL patients with high resolution HLA-matching performed on donors, which has contributed to better outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.17 Our results show no significant difference between RD and 8/8 URD recipients in overall survival, leukemia-free survival, and transplant-related mortality. In contrast, 7/8 URD recipients had a greater incidence of adverse outcomes, with the multivariate model showing an increased risk of death from any cause and transplant-related mortality. Recipients of 7/8 URD HCT had worse LFS compared to RD and 8/8 URD, however this difference only reached statistical significance when compared to 8/8 URD. We hypothesize that the 7/8 URD group's lower relapse rates account for the similarity in LFS when compared to RD transplants. However, the 7/8 URD group's higher mortality risk can be attributed to the excessive TRM associated with this donor source. Others have shown mismatched unrelated donor source to have a negative impact on survival, however these studies were limited by small sample size or by restricting their patient population to Philadelphia chromosome negative patients transplanted in first remission.18,19 We have confirmed these findings, and have done so over a broad spectrum of ALL patients.

Tomblyn et al previously found similar outcomes when comparing RD with matched and partially-matched unrelated donors, however their patient population was limited in size (matched unrelated donor, n=19; partially-matched unrelated donor, n=23), and also focused on an overall younger population.15 Our study found that recipients age>52 was associated with significantly worse OS compared to younger patients. Given that they also found recipient age to have an impact on outcomes, their study's overall younger population may account for some of the similarities in outcomes between related and unrelated donors. The authors postulated that for patients transplanted in CR2, perhaps a longer duration of CR1 represented a prognostic indicator for risk of adverse outcomes, which our study has shown to be true; OS, LFS, and relapse were all negatively impacted when patients were transplanted in CR2 with a CR1 duration of <=30 months. Furthermore, when restricting our population only to patients transplanted in CR1, we found results similar to that of the entire study population.

Another aspect of HCT we aimed to address in this study was whether the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect plays a role in outcomes. Patients undergoing RIC HCT rely more on the GVL effect of their transplant to prevent disease relapse.10 Reduced intensity conditioning combined with RD transplant has been shown to be a viable option for those not eligible for MAC, however, conditioning regimen intensity was only addressed for RD transplants, without any comparison to URDs.20 Marks et al directly compared conditioning regimens in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative ALL receiving RD or URD transplants after undergoing full-intensity or reduced-intensity conditioning, finding similar OS, LFS, and relapse rates regardless of conditioning intensity.21 We have also shown there to be no difference in OS or LFS when comparing MAC with TBI versus MAC without TBI versus RIC across all donor sources, however, given the small sample size of those receiving chemotherapy-based myeloablative conditioning (n=164), the statistical power to detect a difference is limited. Our multivariate analysis showed that URD recipients have a lower relapse risk than RD recipients. The development of chronic GVHD has been previously associated with decreased relapse rates.22 Mohty et al demonstrated that patients who received a reduced intensity conditioning regimen and subsequently developed chronic GVHD had greater OS than those without chronic GVHD.20 In our analysis, the URD groups had a greater risk of cGVHD, which may account for the decreased risk of relapse in these groups. While the URD groups had less risk of relapse, they did not benefit from improved LFS, likely due to higher incidence of acute and chronic GVHD and subsequently higher rates of TRM. Although URD recipients did suffer less frequent relapse, the incidence in all three groups remains excessive, and further investigation should be made into strategies to reduce this incidence.

Additionally, while Philadelphia chromosome has traditionally been considered a prognostic factor for adverse outcomes,23,24 Postow et al found that it may not be an adverse factor in contemporary practice.25 Our results showed that presence of Philadelphia chromosome did not have a negative impact on any outcomes, while Philadelphia chromosome negative patients had greater risk of relapse compared to Ph+ patients. We speculate that this is due to increased used of TKIs in the treatment of Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL.

Historically, peripheral blood and bone marrow transplants have been shown to have similar survival outcomes in both related and unrelated donor recipients with a wide array of hematologic malignancies, though peripheral blood has been associated with greater incidence of chronic GVHD.26,27 Our study confirmed peripheral blood transplant as a risk factor for cGVHD, as well as for acute GVHD. Furthermore, at >24 months post-HCT, peripheral blood was associated with greater risk of TRM and all-cause mortality. The initial results of BMT CTN 0201, a prospective trial comparing outcomes in BM vs PBSC transplants, have shown similar OS, disease-free survival, and TRM between graft types, higher rates of chronic GVHD in PBSC recipients, and superior 5-year psychological well-being and quality of life scores in bone marrow recipients.27,28 Given these results, as well as our own findings, we recommend using BM grafts whenever possible.

In summary, our study confirms that in the absence of RD, use of 8/8 URD yields similar survival, while 7/8 URD is associated with inferior survival. 8/8 URD was associated with 30% higher probability of chronic GVHD compared to RD. Therefore, despite similar survival between 8/8 URD and RD, we conclude that RD remains the gold-standard. HCT from an 8/8 URD should be considered a reasonable alternative when 8/8 URD is the only available donor.

Future studies comparing haploidentical to 7/8 URD transplants will be critical in determining optimal alternative donor type when a matched donor could not be identified. These results should inform clinicians, patients, and researchers in their design of prospective clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), which is supported by a Public Health Service grant (cooperative agreement 5U24-CA076518) from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); by the NHLIB and the NCI (grant/cooperative agreement 5U10HL069294); by the Health Resources and Services Administration/Department of Health and Human Services (contract HHSH250201200016C; grants N00014-13-1-0039 and N00014-14-1-0028) from the Office of Naval Research; by an anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; and by grants from Alexion; Amgen, Inc (a corporate member); Be the Match Foundation; Bristol-Myers Squibb Oncology (a corporate member); Celgene Corporation (a corporate member); Chimerix, Inc (a corporate member); the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida Cell Ltd; Genentech, Inc; Genzyme Corporation; Gilead Sciences, Inc (a corporate member); Health Research, Inc; the Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc; Incyte Corporation; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc (a corporate member); Jeff Gordon Children's Foundation; The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck and Company, Inc; Mesoblast; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Company; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc (a corporate member); the National Marrow Donor Program; Neovii Biotech NA, Inc; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Health Care Solutions, Inc; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd-Japan; Oxford Immunotec; Perkin Elmer, Inc; Pharmacyclics; Sanofi US (a corporate member); Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc (a corporate member); St Baldrick's Foundation; Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc (a corporate member); Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc; Telomere Diagnostics, Inc; TerumoBCT; Therakos, Inc; the University of Minnesota; and Wellpoint, Inc (a corporate member).

Footnotes

Contributions: Eric Segal, Michael Martens, Hai-Lin Wang, Ruta Brazausaks, Wael Saber: Study design, results analysis, writing- original draft. Daniel Weisdorf, Brenda M. Sandmaier, Jean Khoury, Marcos de Lima: Study design, writing- final review and approval

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Karanes C, Nelson GO, Chitphakdithai P, et al. Twenty Years of Unrelated Donor Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Adult Recipients Facilitated by the National Marrow Donor Program. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14(9, Supplement):8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurley CK, Wagner JE, Setterholm MI, Confer DL. Advances in HLA: Practical Implications for Selecting Adult Donors and Cord Blood Units. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12(1, Supplement 1):28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lennard AL, Jackson GH. Stem cell transplantation. Bmj. 2000;321(7258):433. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grewal SS, Barker JN, Davies SM, Wagner JE. Unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation: marrow or umbilical cord blood? Blood. 2003;101(11):4233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gragert L, Eapen M, Williams E, et al. HLA match likelihoods for hematopoietic stem-cell grafts in the U.S. registry. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;371:339–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1311707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasquini M, Zhu X. Current use and outcome of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR Summary slides. [Accessed April 9, 2016];2015 Available at: http://www.cibmtr.org.

- 7.Hahn T, McCarthy PL, Hassebroek A, et al. Significant improvement in survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation during a period of significantly increased use, older recipient age, and use of unrelated donors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(19):2437–2449. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saber W, Opie S, Rizzo JD, Zhang MJ, Horowitz MM, Schriber J. Outcomes after matched unrelated donor versus identical sibling hematopoietic cell transplantation in adults with acute myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(17):3908. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-381699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saber W, Cutler C, Nakamura R, et al. Impact of donor source on hematopoietic cell transplantation outcomes for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) Blood. 2013;122(11):1974–1982. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weisdorf D, Zhang MJ, Arora M, Horowitz MM, Rizzo JD, Eapen M. Graft-versus-host disease induced graft-versus-leukemia effect: greater impact on relapse and disease-free survival after reduced intensity conditioning. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(11):1727–1733. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meijerink JP. Genetic rearrangements in relation to immunophenotype and outcome in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2010;23(3):307–318. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. The American Journal of Medicine. 1980;69(2):204. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Statistics in medicine. 1999;18(6):695. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomblyn MB, Arora M, Baker KS, et al. Myeloablative Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Analysis of Graft Sources and Long-Term Outcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(22):3634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiehl MG, Kraut L, Schwerdtfeger R, et al. Outcome of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation in Adult Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: No Difference in Related Compared With Unrelated Transplant in First Complete Remission. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(14):2816. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SJ, Klein J, Haagenson M, et al. High-resolution donor-recipient HLA matching contributes to the success of unrelated donor marrow transplantation. Blood. 2007;110(13):4576–4583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-097386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar P, Defor TE, Brunstein C, Barker JN, Wagner JE, Weisdorf DJ, Burns LJ. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia: impact of donor source on survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:1394–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pidala J, Djulbegovic B, Anasetti C, Kharfan-Dabaja M, Kumar A. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in first complete remission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD008818. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008818.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohty M, Labopin M, Volin L, et al. Reduced-intensity versus conventional myeloablative conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a retrospective study from the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2010;116(22):4439. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-266551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marks D, Wang T, Perez W, et al. The outcome of full-intensity and reduced-intensity conditioning matched sibling or unrelated donor transplantation in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first and second complete remission. Blood. 2010;116(3):366–374. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ringd'en O, Pavletic SZ, Anasetti C, et al. The graft versus-leukemia effect using matched unrelated donors is not superior to HLA-identical siblings for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2009;113(13):3110–3118. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-163212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moorman AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, et al. Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council (MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 trial. Blood. 2007;109(8):3189–3197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graux C. Biology of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): clinical and therapeutic relevance. Transfus Apher Sci. 2011;44(2):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Postow M, Kim H, Sun L, et al. Philadelphia Chromosome Is Not an Adverse Prognostic Factor in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia After Myeloablative Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation [abstract] Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17(2):S244–S245. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bensinger W, Martin P, Storer B, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow as compared with peripheral-blood cells from HLA-identical relatives in patients with hematologic cancers. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(3):175–181. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anasetti C, Logan B, Lee S, et al. Peripheral-blood stem cells versus bone marrow from unrelated donors. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(16):1487–1496. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Logan B, Westervelt P, et al. 5 year results of BMT CTN 0201: Unrelated donor bone marrow is associated with better psychological well-being and less burdensome chronic GVHD symptoms than peripheral blood [abstract] Blood. 2015;126(3):270. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.