Abstract

Background

Although patients with blood cancers have significantly lower rates of hospice use compared to those with solid malignancies, data explaining this gap in end-of-life care are sparse.

Methods

In 2015, we conducted a mailed survey of a randomly selected sample of hematologic oncologists in the United States to characterize their perspectives regarding the utility and adequacy of hospice for blood cancer patients, as well as factors that might impact referral patterns. Simultaneous provision of care for patients with solid malignancies was permitted.

Results

We received 349 surveys (response rate=57.3%). The majority of respondents (68.1%) strongly agreed that hospice care is “helpful” for patients with hematologic cancers; those with practices including greater numbers of solid tumor patients (at least 25%) were more likely to strongly agree (OR=2.10, 95% CI 1.26, 3.52). Despite high levels of support for hospice in general, 46.0% felt that home hospice is “inadequate” for their patients’ needs (as compared to inpatient hospice with round-the-clock care). While over half of respondents reported they would be more likely to refer to hospice if red cell and/or platelet transfusions were available, those who considered home hospice inadequate were even more likely to report they would (67.3% vs. 55.3%, p=0.03 for red cells and 52.9% vs. 39.7%, p=0.02 for platelets).

Conclusions

These data suggest that although hematologic oncologists value hospice, concerns about adequacy of services for blood cancer patients limit hospice referrals. To increase hospice enrollment for blood cancer patients, interventions tailoring hospice services to their specific needs are warranted.

Keywords: Hospice, end-of-life care, blood cancers, hematologic oncologists, palliative care

INTRODUCTION

Since the establishment of the first United States (US) hospice program in 1974, empiric evidence has increasingly demonstrated its positive impact on the care of patients with life-limiting illnesses.1–4 For example, hospice enrollment has been shown to improve patient quality of life at the end of life (EOL) and lower the risk of psychiatric disorders among bereaved caregivers.2, 4 A recent analysis also demonstrated that patients with poor-prognosis cancers who receive hospice care have a lower incidence of hospital admissions, intensive care unit admissions, and invasive procedures during the last year of life compared to those who are not admitted to hospice.3 In light of accruing evidence regarding its benefits, timely hospice enrollment is now endorsed as an indicator of high-quality EOL care.5, 6 Indeed, hospice is a widely established model of symptom-directed care for patients with an estimated life expectancy of six months or less.

Although hospice is now recognized as a vital aspect of EOL care, only a minority of patients who die of hematologic cancers in the US enroll. Moreover, they have the lowest rates of hospice use among all oncology patients.7–9 In a large population-based analysis of 215,800 individuals 65 years or older who died from cancer between 1991 and 2000, blood cancer patients were the least likely to enroll in hospice and when they did enroll, they were likely to spend less time there compared to other patients.8 About a decade later, a study of over 64,000 patients demonstrated similar results: patients with hematologic cancers had 52% higher odds of a hospice length of stay ≤ 3 days compared to those with solid malignancies.9

Few studies have explored the causes of lower rates of hospice use among patients with hematologic malignancies.10, 11 Specifically, it is not known whether hematologic oncologists’ views about the utility of hospice or services available in hospice settings explain the low rates of hospice enrollment for patients with blood cancers. In addition, data are limited regarding factors that may influence hospice referral practices of hematologic oncologists. We thus surveyed a national sample of US-based hematologic oncologists to characterize their perspectives regarding the usefulness of hospice for patients with blood cancers and their referral practices. Given that in oncology, the current hospice model is largely designed to support the needs of patients with metastatic solid tumors (e.g. pain control), we hypothesized that hematologic oncologists who predominantly provide care for blood cancer patients would be less likely to consider hospice to be helpful. Moreover, given prior literature regarding the intensive caregiving needs of blood cancer patients at the EOL coupled with the fact that the US model of hospice is predominantly outpatient/home-based,12 we hypothesized that most respondents would consider home hospice to be inadequate for the level of care required for this patient population.

METHODS

Study Population

We conducted a mailed survey of US-based hematologic oncologists providing care for adult blood cancer patients. We identified potential participants from the clinical directory of the American Society of Hematology (ASH). This web-based directory provides practice address, telephone number, and clinical interests of hematologic oncologists. Screening telephone calls were placed to the practices of all listed adult hematologic oncologists to confirm eligibility (i.e. “Does Doctor X take care of blood cancer patients?”) and validity of mailing address. Simultaneous provision of care for patients with solid malignancies was permitted.

Data Collection

We administered our survey between September, 2014 and January, 2015 to a total of 667 hematologic oncologists. Subjects received an express mail package that included a cover letter, the survey, an opt-out card (with the opportunity to check a box reporting that the physician does not routinely treat blood cancers), a postage-paid return envelope, and a $25 gift card. Subjects were also given the option to complete the survey online. Reminder post-cards were sent at two and four weeks after the initial mailing, and a telephone reminder call was made by a physician investigator (OO) at six weeks to non-respondents. Another mailing was sent to non-respondents in January, 2015 to encourage participation. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center.

Survey Instrument

The survey instrument included 30 questions examining various aspects of EOL care for patients with hematologic cancers. The survey was developed using qualitative data from hematologic oncologists,11 adaptation of previously published instruments,13–16 and literature review. The survey was pilot-tested and revised according to feedback from cognitive debriefing with five practicing hematologic oncologists.

To examine perspectives regarding hospice, we asked participants, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree,” how strongly they agreed with the statement, “Hospice care is helpful for my patients.” They were also asked to rate their level of agreement with several other statements regarding adequacy of hospice services for blood cancer patients and factors that might impact referral practices, including: 1) “I feel home hospice is not adequate for the level of care some of my patients need,” 2) “My patients feel home hospice is not adequate for the level of care they need,” 3) “I would rather refer my patients to an inpatient hospice facility than home hospice,” 4) “I would refer more patients to hospice if red blood cell transfusions were allowed,” 5) “I would refer more patients to hospice if platelet transfusions were allowed,” and 6) “I would refer more patients to hospice if I were able to have clinic visits with them more often.” Several of the statements above focused on home hospice as this is the prevalent model of providing hospice care in the US and also because there are stringent admission criteria for general inpatient level of hospice care, which are largely based on management of pain crises. We also asked participants if they agreed with the statement “If I were terminally ill with cancer, I would enroll in hospice,” using a 5-point Likert scale. Of note, the survey instructions specified that questions referred to hematologic malignancies only. Respondents provided personal and practice characteristics including age, gender, years since medical school graduation, board certification, academic center affiliation, practice setting, and provision of hematopoietic cell transplant care.

Statistical Analysis

We first descriptively summarized perspectives regarding hospice. We then conducted univariable analyses (Chi-square tests) to assess which factors were associated with perceptions about the utility of hospice and preferences regarding whether respondents would enroll in hospice if they themselves were terminally ill with cancer. We chose to dichotomize responses into strong agreement versus other for the above analyses for two reasons. First, given that hospice is endorsed as a marker of high-quality EOL care, we felt that social desirability may influence respondents to agree that hospice is helpful, and that strong agreement would be more reflective of true belief in hospice’s utility. Second, the survey from which we adapted the item regarding personal hospice preferences was analyzed with this same dichotomy.16,17

Next, we created multivariable logistic regression models to identify factors independently associated with (1) strong agreement that hospice is helpful and (2) strong agreement to enroll in hospice if terminally ill. The models included factors with significance levels of p<0.10 from the univariable analysis; we planned to force gender and years since graduation from medical school into the models regardless of significance. Finally, referral practices associated with agreement/strong agreement that home hospice is not adequate for patients with hematologic cancers were examined descriptively using Chi-squared tests. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Respondents

Among 667 hematologic oncologists surveyed, 58 were ultimately ineligible because they reported on their opt-out card that they were not routinely providing care to adult patients with blood cancers despite having been screened in prior telephone calls (N=29) or they were no longer at the ASH directory address and had no known forwarding address (N=29). Of the 609 eligible respondents, 349 hematologic oncologists from 48 states completed the survey (response rate 57.3%). 75.6% of the cohort was male, median age was 52 years (interquartile range [IQR] 44 to 60 years), and median number of years since medical school graduation was 25 (IQR 17 to 33 years). 51.6% of respondents reported that at least 25% of their patient population had solid tumors. Additional respondent characteristics are noted in Table 1. Non-respondents did not differ significantly from respondents with respect to gender (p=0.06) and region of practice (p=0.72).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participating Hematologic Oncologists (N=349)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Male | 264 (75.6) |

|

| |

| Age ≤ 40years | 45 (12.9) |

| Age > 40 years | 294 (84.2) |

|

| |

| ≤ 15 years since med school graduation | 74 (21.2) |

| > 15 years since med school graduation | 267 (76.5) |

|

| |

| Board-certified in medical oncology | 302 (86.5) |

|

| |

| Board-certified in hematology | 282 (80.8) |

|

| |

| Board-certified in both medical oncology and hematology | 247 (70.8) |

|

| |

| Closely affiliated with academic center | 217 (62.2) |

| Not closely affiliated with academic center | 132 (37.8) |

|

| |

| Primary practice | |

| Tertiary center | 150 (43.0) |

| Community center* | 192 (55.0) |

|

| |

| Provides autologous or allogeneic transplant services | 141 (40.4) |

|

| |

| Practice with < 25% of patients with solid malignancies | 169 (48.4) |

| Practice with ≥ 25% of patients with solid malignancies | 180 (51.6) |

|

| |

| Method of learning to provide EOL care** | |

| Role models | 270 (77.4) |

| Trial and error in clinical practice | 254 (72.8) |

| Conferences and lectures | 204 (58.5) |

| Rotation on palliative care or hospice | 66 (18.9) |

|

| |

| Region | |

| Midwest | 83 (23.8) |

| Northeast | 106 (30.4) |

| South | 108 (30.9) |

| West | 52 (14.9) |

Not all columns add up to 100% because of item non-response.

Among respondents in community centers, 168 practiced primarily in community centers, while 24 had a hybrid practice in community and tertiary centers

Categories are not mutually exclusive; respondents could select multiple ways in which they learned to provide EOL care

Hospice Care for Blood Cancer Patients

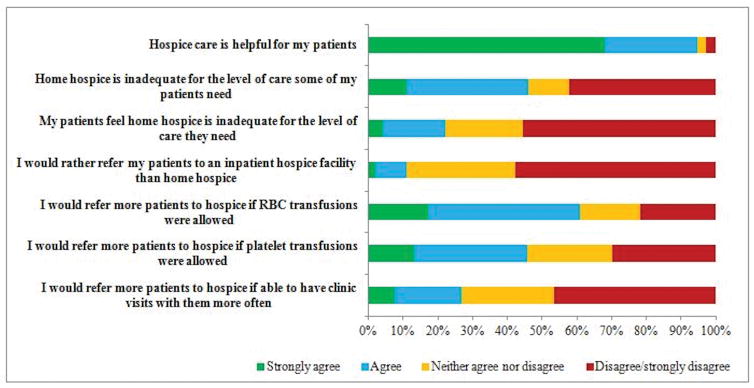

Among those who answered all questions regarding hospice care for their blood cancer patients, the majority strongly agreed (68.1%) that hospice is “helpful” (Figure 1). In adjusted multivariable analysis, respondents who were >15 years from medical school graduation were more likely to strongly agree that hospice is helpful (OR=2.42, 95% CI 1.38, 4.22) and those who reported that at least 25% of their patient population had a solid malignancy had higher odds of strongly agreeing that hospice is helpful (OR=2.10, 95% CI 1.26, 3.52; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Hematologic oncologists’ perspectives regarding hospice care for patients with hematologic cancers at the end of life (n=332)

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable analyses of factors associated with hematologic oncologists’ perspectives of helpfulness of hospice for patients with blood cancers

| Univariable Analysis | MV Analysis§; Outcome modeled: Strongly agree that hospice care is helpful | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Characteristic | Strongly agree hospice care is helpful N =226 % |

Less than strong agreement N=106 % |

Chi-square P-value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|

| ||||||

| Male | 80.1 | 68.9 | 0.02 | -- -- | 0.37, 1.10 | 0.11 |

| Female | 19.9 | 31.1 | 0.64 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age ≤ 40years* | 10.0 | 21.4 | 0.006 | -- | -- | |

| Age > 40 years* | 90.0 | 78.6 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ≤ 15 years since med school graduation* | 17.2 | 32.7 | 0.002 | -- -- | 1.38, 4.22 | 0.002 |

| > 15 years since med school graduation* | 82.8 | 67.3 | 2.42 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Closely affiliated with academic center | 56.6 | 74.5 | 0.002 | -- | -- | |

| Not closely affiliated with academic center | 43.4 | 25.5 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Primary practice* | <0.001 | -- | -- | |||

| Tertiary center | 36.5 | 60.0 | ||||

| Community center | 63.5 | 40.0 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Practice with < 25% of patients with solid malignancies | 41.6 | 61.3 | 0.0008 | -- -- | 1.26, 3.52 | 0.005 |

| Practice with 25% of patients with solid malignancies | 58.4 | 38.7 | 2.10 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Provides auto- or allo-transplant services | 37.6 | 48.1 | 0.07 | -- -- | 0.79, 2.22 | 0.29 |

| Does not provide auto- or allo- transplant services | 62.4 | 51.9 | 1.33 | |||

|

| ||||||

| No rotation on palliative care or hospice service | 81.9 | 78.3 | 0.44 | -- | -- | |

| Rotation on palliative care/hospice service | 18.1 | 21.7 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Region | 0.85 | -- | -- | |||

| Midwest | 23.4 | 26.4 | ||||

| Northeast | 30.1 | 30.2 | ||||

| South | 31.0 | 31.1 | ||||

| West | 15.5 | 12.3 | ||||

Percentages are column percentages, and exclude individuals for whom characteristic was not reported. Characteristic non-response range from 1.5% for primary practice to 2.7% for age.

Multivariable model included variables with p <0.10 from univariable analysis in the model. Because proportion of solid malignancy patients in one’s practice is co-linear with practice setting (tertiary setting vs. community) and academic center affiliation, only proportion of solid patients was included in the model. Similarly, given that age and years since medical school graduation are co-linear, only time since medical school graduation was included in model.

A substantial proportion (46.0%) agreed or strongly agreed that home hospice is not adequate for the level of care their patients need, and 26.8% agreed or strongly agreed they would refer more patients if they could continue to have regular clinic visits after hospice begins. With regards to transfusions, 61.7% agreed or strongly agreed that they would refer more patients to hospice if red cell and/or platelet transfusions were allowed. Moreover, 60.8% agreed or strongly agreed that they would refer more patients if red cell transfusions were allowed, and 45.6% would do so if platelet transfusions were allowed. Those who considered home hospice to be inadequate were even more likely to report they would refer more patients if red cell (67.3% vs. 55.3%, p=0.03) or platelet transfusions were allowed (52.9% vs. 39.7%, p=0.02), and if they could continue to have regular clinic visits (36.0% vs. 19.0%, p=0.0005).

Personal Preference Regarding Hospice Enrollment if Terminally Ill

Over half of respondents (52.4%) strongly agreed that they would enroll in hospice if they themselves were terminally ill with cancer. In adjusted multivariable models, hematologic oncologists who had previously rotated on a palliative care or hospice service (OR=1.97, 95% CI 1.08 to 3.58) and those for whom ≥ 25% of their practice consisted of patients with solid tumors (OR=1.99, 95% CI 1.28 to 3.11; Table 3) were more likely to strongly agree they themselves would enroll in hospice.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable analyses of factors associated with hematologic oncologists’ perspectives to enroll in hospice themselves if terminally ill with a hematologic cancer.

| Univariable Analysis | MV Analysis§; Outcome modeled: strongly agree to enroll in hospice if terminally will with cancer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Characteristic | Strongly agree to enroll in hospice N =183 % |

Less than strong agreement N=159 % |

Chi- square P-value | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|

| ||||||

| Male | 73.2 | 77.4 | 0.38 | -- -- | 0.88, 2.47 | 0.14 |

| Female | 26.8 | 22.6 | 1.48 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age ≤ 40years* | 15.8 | 10.9 | 0.19 | -- | -- | |

| Age > 40 years* | 84.2 | 89.1 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ≤ 15 years since med school graduation* | 21.8 | 22.4 | 0.89 | -- -- | 0.72, 2.20 | 0.41 |

| > 15 years since med school graduation* | 78.2 | 77.6 | 1.26 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Closely affiliated with academic center | 57.4 | 66.7 | 0.08 | -- | -- | |

| Not closely affiliated with academic center | 42.6 | 33.3 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Primary practice* | 0.005 | -- | -- | |||

| Tertiary center | 36.5 | 51.9 | ||||

| Community center | 63.5 | 48.1 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Practice with < 25% of patients with solid malignancies | 42.1 | 55.4 | 0.014 | -- -- | 1.28, 3.11 | 0.002 |

| Practice with ≥ 25% of patients with solid malignancies | 57.9 | 44.6 | 1.99 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Provides auto- or allo-transplant services | 40.4 | 40.9 | 0.93 | -- | -- | |

| Does not provide auto- or allo- transplant services | 59.6 | 59.1 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| No rotation on palliative care or hospice service | 77.6 | 84.9 | 0.09 | -- -- | 1.08, 3.58 | 0.03 |

| Rotation on palliative care/hospice service | 22.4 | 15.1 | 1.97 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Region | 0.10 | -- | -- | |||

| Midwest | 22.9 | 24.5 | ||||

| Northeast | 27.9 | 32.1 | ||||

| South | 29.5 | 33.3 | ||||

| West | 19.7 | 10.1 | ||||

percentages are column percentages, and exclude individuals for whom characteristic was not reported. Characteristic non-response range from 1.7% for primary practice to 2.6% for age.

Multivariable model included variables with p <0.10 from univariable analysis in the model and forced in gender and years since medical school graduation. Because proportion of solid malignancy patients in one’s practice is co-linear with practice setting (tertiary setting vs. community) and academic center affiliation, only proportion of solid patients was included in the model.

DISCUSSION

In this national sample of hematologic oncologists, the majority strongly agreed that hospice care is helpful for patients with blood cancers, and slightly over half strongly agreed that they themselves would enroll in hospice if terminally ill with cancer. These perceptions were more positive among hematologic oncologists who also reported seeing a substantial number of patients with solid tumors. Despite the overall positive perception, a significant proportion of respondents felt home hospice is not adequate for the level of care needed for blood cancer patients. Moreover, those who considered home hospice to be inadequate were more likely to report that they would increase referrals if transfusions were readily available. Taken together, these findings suggest that although hematologic oncologists value hospice, rates of referral are relatively low because the current hospice model may not meet the practical needs of blood cancer patients.

Indeed, given low rates of timely hospice use among blood cancer patients,7–10 our finding that most hematologic oncologists considered hospice care to be helpful was surprising. This finding suggests that the perceived utility of hospice by hematologic oncologists is not a substantial contributor to hospice underuse among patients with blood cancers. The discordance between the stated belief that hospice is helpful and the revealed experience of low hospice rates for blood cancer patients with blood cancers may be partly explained by the viewpoint held by several respondents that home hospice is not adequate for the level of care needed.

A recent study showed that needs of patients with hematologic cancers who enrolled in hospice were distinct from those with solid malignancies in that they were more seriously ill, had worse functional status, and were more likely to need hospice services in inpatient settings.12 Indeed, this difference in symptom burden may explain our finding that hematologic oncologists with very few or no solid tumor patients in their practice had less favorable perceptions of hospice. The need for transfusions for some blood cancer patients may also discourage enrollment.7, 10, 11 For example, in a study of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes, those who were transfusion-dependent had significantly lower odds of enrolling. Moreover, the fact that pain—a major focus of hospice—is less prevalent among patients with hematologic cancers compared to solid malignancies may further foster the viewpoint that hospice services are less relevant.10

Our data suggest that rather than further educating hematologic oncologists on the value of hospice, interventions that tailor hospice services to their specific patient needs are more likely to be effective at increasing enrollment. Respondents who considered home hospice inadequate for blood cancer patients were more likely to report that they would increase hospice referrals if certain care elements considered important for blood cancer patients could be provided. Moreover, even among respondents who considered home hospice to be adequate, the majority reported that they would refer more patients if red cell transfusions were allowed.

Although transfusions are palliative in nature, most hospices are unable to provide this resource in the US because payers such as Medicare reimburse at a fixed daily rate per patient regardless of actual services provided. Accordingly, interventions to make additional resources available through hospice will necessitate policy changes regarding hospice reimbursement. While there would be added costs for provision of transfusions, there would likely be concomitant cost savings through increased hospice enrollment leading to reduction in terminal hospitalizations and/or intensive, non-efficacious treatments.3, 18, 19

Our finding that over a quarter of respondents would refer more patients to hospice “if they could have clinic visits with them more often” likely reflects a desire of hematologic oncologists to maintain face-to-face involvement in their patients’ care, even when the treatment phase has passed.20 The varying disease trajectories of hematologic cancers—some with chronic courses requiring frequent and long-term follow-up, and others with high-intensity courses that necessitate weeks of inpatient care with close outpatient follow-up—foster strong patient/provider bonds. Moreover, hematologic oncologists may be concerned that their patients would feel a sense of abandonment if they are no longer visibly involved in their care. Given that arranging travel to clinic visits while in hospice is burdensome, this issue could be potentially addressed with innovative models that include so-called “shared care” or telemedicine.21

Although external factors may impact hospice referrals, physicians’ personal preferences regarding the care they themselves would like to receive at the EOL have also been shown to influence their approach to EOL care with patients.17, 22 While most of our respondents strongly agreed they would enroll in hospice if terminally ill (52.4%), the proportion was lower than in a prior survey of solid tumor oncologists asked the same question (64.5%).17 This variation in personal preferences may partly account for differences in hospice referrals by hematologic oncologists.8, 9 On the other hand, their clinical experience of taking care of blood cancer patients near the EOL—and resulting perceptions regarding the inadequacy of hospice—may actually drive their personal preferences.

Our study has limitations. First, social desirability bias may have influenced hematologic oncologists’ responses such that a large number reported that they felt hospice is helpful; we attempted to account for this possibility by focusing our analyses on those reporting strong agreement. Second, because our survey asked about blood cancers in general, our data may not capture views about the adequacy of hospice for specific hematologic cancers. For example, it is possible that several hematologic oncologists consider hospice inadequate for patients with acute leukemia because transfusion support is a common need for this population. Conversely, many may consider hospice particularly suited for patients with myeloma because the need for pain control is highly prevalent.23 Third, our survey focused on views regarding hospice and rates of referral, and did not specifically elicit perspectives regarding timeliness of referral or length of hospice stay. Fourth, our data describe hematologic oncologists’ self-reports of potential changes in referral practices based on theoretical factors (e.g., availability of transfusions) and may not reflect how such factors would actually change practice. Finally, despite an acceptable response rate for a physician survey and although there were no significant differences between respondents and non-respondents based on sex and region of practice, our analysis may still suffer from participation bias associated with characteristics not captured.

The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization defines hospice as a “model for quality, compassionate care for people facing a life-limiting illness...[that] involves a team-oriented approach to expert medical care, pain management, and emotional and spiritual support expressly tailored to the patient’s needs and wishes.”24 Our analysis suggests that most hematologic oncologists value the hospice philosophy; however, they are less supportive when asked questions assessing whether hospice is “expressly tailored” to the needs of patients with blood cancers. Moreover, new models of hospice that more expansively address these needs—such as allowing red cell transfusions and continuing oncologist visits—will be essential to improving enrollment and quality of EOL care for this patient population.

Acknowledgments

Support: O.O Odejide received research support from the National Palliative Care Research Center Junior Faculty Career Development Award, Harvard Medical School Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership Faculty Fellowship, and Program in Cancer Outcomes Research Training Fellowship from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health [NCI, R25CA092203].

Footnotes

Disclosures: no relevant financial interests to disclose

Authorship Contributions

O.O.O designed and performed research, performed statistical analysis, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. A.M.C. performed statistical analysis, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. C.E. designed research, analyzed, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. J.T. analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. G.A.A. designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, Matulonis UA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers’ mental health. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4457–4464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obermeyer Z, Makar M, Abujaber S, Dominici F, Block S, Cutler DM. Association between the medicare hospice benefit and health care utilization and costs for patients with poor-prognosis cancer. JAMA. 2014;312:1888–1896. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kris AE, Cherlin EJ, Prigerson H, et al. Length of Hospice Enrollment and Subsequent Depression in Family Caregivers: 13-Month Follow-Up Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14:264–269. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000194642.86116.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. [accessed December 6, 2016];The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative Quality Measures. Available from URL: http://qopi.asco.org/documents/QOPI-Spring-2014-Measures-Summary.pdf.

- 6.National Quality Forum. [accessed December 6, 2016];National Voluntary Consensus Standards: Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care: A Consensus Report. Available from URL: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/04/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care%e2%80%94A_Consensus_Report.aspx.

- 7.Sexauer A, Cheng MJ, Knight L, Riley AW, King L, Smith TJ. Patterns of hospice use in patients dying from hematologic malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:195–199. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3860–3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connor NR, Hu R, Harris PS, Ache K, Casarett DJ. Hospice Admissions for Cancer in the Final Days of Life: Independent Predictors and Implications for Quality Measures. J Clin Oncol. 2014 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.8817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher SA, Cronin AM, Zeidan AM, et al. Intensity of end-of-life care for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes: Findings from a large national database. Cancer. 2016;122:1209–1215. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Odejide OO, Salas Coronado DY, Watts CD, Wright AA, Abel GA. End-of-life care for blood cancers: a series of focus groups with hematologic oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:e396–403. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP, Casarett DJ. What is different about patients with hematologic malignancies? A retrospective cohort study of cancer patients referred to a hospice research network. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durall A, Zurakowski D, Wolfe J. Barriers to conducting advance care discussions for children with life-threatening conditions. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e975–982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley EH, Cramer LD, Bogardus ST, Jr, Kasl SV, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Horwitz SM. Physicians’ ratings of their knowledge, attitudes, and end-of-life-care practices. Acad Med. 2002;77:305–311. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abel GA, Friese CR, Neville BA, et al. Referrals for suspected hematologic malignancy: a survey of primary care physicians. Am J Hematol. 2012;87:634–636. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chinn GM, Liu P, Klabunde CN, Kahn KL, Keating NL. PHysicians’ preferences for hospice if they were terminally ill and the timing of hospice discussions with their patients. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174:466–468. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Jawahri AR, Abel GA, Steensma DP, et al. Health care utilization and end-of-life care for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2015;121:2840–2848. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks GA, Li L, Uno H, Hassett MJ, Landon BE, Schrag D. Acute hospital care is the chief driver of regional spending variation in Medicare patients with advanced cancer. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1793–1800. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeBlanc TW, O’Donnell JD, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among hematologic malignancy specialists: a mixed-methods study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e230–238. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitten P, Doolittle G, Mackert M. Telehospice in Michigan: use and patient acceptance. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21:191–195. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daugherty CK, Hlubocky FJ. What Are Terminally Ill Cancer Patients Told About Their Expected Deaths? A Study of Cancer Physicians’ Self-Reports of Prognosis Disclosure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:5988–5993. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramsenthaler C, Kane P, Gao W, et al. Prevalence of symptoms in patients with multiple myeloma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Haematology. 2016;97:416–429. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Organization NHaPC. Hospice & Palliative Care. [accessed December 6, 2016];National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Available from URL: http://www.nhpco.org/about/hospice-care.