Abstract

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is a serious complication in organ transplant recipients and is most often associated with the Epstein Barr virus (EBV). EBV is a common gammaherpes virus with tropism for B lymphocytes and infection in immunocompetent individuals is typically asymptomatic and benign. However, infection in immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals can result in malignant B cell lymphoproliferations such as PTLD. EBV+ PTLD can arise following primary EBV infection, or because of reactivation of a prior infection, and represents a leading malignancy in the transplant population. The incidence of EBV+ PTLD is variable depending on the organ transplanted and whether the recipient has preexisting immunity to EBV but can be as high as 20%. It is generally accepted that impaired immune function due to immunosuppression is a primary cause of EBV+ PTLD. In this overview, we review the EBV life cycle and discuss our current understanding of the immune response to EBV in healthy, immunocompetent individuals, in transplant recipients, and in PTLD patients. We review the strategies that EBV utilizes to subvert and evade host immunity and discuss the implications for the development of EBV+ PTLD.

Introduction

Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) comprises a complex spectrum of abnormal lymphoid proliferations that arise in immunosuppressed organ transplant recipients. Though the large majority of solid organ PTLD cases involve recipient B lymphocytes that are infected with the Epstein Barr virus (EBV), other forms of PTLD can include T cell or NK cell lymphoproliferations and may be EBV−. The prognosis of PTLD is variable, in accordance with the histologic heterogeneity that is captured in the World Health Organization classification of 2008 (1). Here we focus on the EBV+ B cell lymphomas in PTLD, a leading life-threatening malignancy in the transplant population.

EBV+ PTLD can arise following a primary infection as when an EBV− recipient receives a graft from an EBV+ donor or when the virus is acquired in the community during the posttransplant period, but EBV+ PTLD can also result from the reactivation of a prior infection. Transplant recipients who acquire the virus in the early posttransplant period as a primary infection are at highest risk for EBV+ PTLD due to the absence of a memory response to the virus. However, late PTLD also can arise and appear to have distinct characteristics from early PTLD (2). The incidence of EBV+ PTLD also depends upon the organ transplanted with the highest incidence found in small intestine and lung recipients and the lowest incidence found in kidney (3). A major contributing factor to the development of PTLD in EBV-infected transplant recipients is the immunosuppression administered to prevent graft rejection. Indeed, the importance of immunosuppression in PTLD has been documented extensively, particularly the impact of the cumulative amount and duration of immunosuppression (4, 5). Similar EBV+ B cell lymphomas have been described in individuals with AIDS (6), the elderly (7), and in patients with primary immunodeficiences (8). The common theme in each of these scenarios is impaired T cell function, either intentional because of immunosuppression in transplant recipients, or acquired as in patients with HIV, genetic deficiencies, or aging immune systems. This deficit in T cell function seems to open a window for uncontrolled expansion of EBV-infected B cells. The importance of T cells in the control of EBV in healthy individuals has been well described (9). The enigma in the transplant scenario however, is that virtually all organ recipients receive chronic immunosuppression that targets T cells, and EBV infection is ubiquitous, yet only a subset of patients develops PTLD. This raises the possibility that more nuanced aspects of the immune system, rather than simply global immunosuppression, may explain which patients are vulnerable to EBV+ PTLD and which patients are protected. The purpose here is to focus on the biology of EBV and the host immune response to the virus, both in immunocompetent individuals and in transplant recipients, and what we can learn from these different situations that may provide new insights into understanding the pathogenesis of PTLD.

Biology of EBV infection and viral persistence

EBV has infected more than 90% of the world’s population, and in the clear majority of cases, infection does not lead to any clinical symptoms. Primary infection usually results from transfer of the virus in the saliva of an EBV+ individual to an EBV− individual whereupon the virus can infect cells, probably of epithelial origin within the oropharynx region, establish a productive infection and elicit the release of active virions and shedding into the throat. During this process, mucosal B cells can also become infected but here the viral cycle shifts to a latent, growth phase resulting in the development of EBV+ proliferating B cell blasts that can move into the periphery (Fig. 1). The expansion of these EBV+ B lymphoblastoid cells is typically controlled by a vigorous T cell response directed against an array of viral latent cycle proteins expressed by the B cells. However, some infected B cells emerge in the memory B cell compartment where viral gene expression is mainly silenced thereby promoting immune escape and viral persistence. Measurements to determine the number of these latently infected B cells in the circulation of healthy individuals indicate they range from 1–50 cells per 106 B cells but this small reservoir of virus is sufficient to maintain chronic infection for the lifetime of the host (10). The memory B cells harboring the virus can move between the circulation and lymphoid tissue within the oropharynx region and periodically reactivate the viral lytic cycle to seed the oropharynx with new viral particles thereby reestablishing and replenishing the viral life cycle. In this manner, the virus can co-exist with the immune system and establish a lifelong infection. Primary infection with EBV usually occurs in childhood, however, when primary infection is delayed until adolescence a different picture can emerge. In this setting, infectious mononucleosis (IM) can occur, an acute process with clinical symptoms including fever, lymphadenopathy, and sore throat, that is accompanied by the massive expansion of activated CD8+ T cells and the presence of large numbers of infected, lymphoblastoid-like B cells in the blood. IM is self-limiting with the culling of expanded T cell populations and resolution of disease, though viral shedding can be detected in the saliva of convalescing patients for several months (11). Still there are many basic questions that remain to be definitively answered about this general picture of the viral life cycle including the specific cell type initially infected by EBV in the oral mucosa, the extent to which mucosal B cells are targets of primary infection relative to epithelial cells, the mechanism by which latently infected cells become reactivated to reinitiate the lytic cycle, how the infected memory B cells originate, either through the progression of infected naïve B cells via a germinal center-like reaction or through direct infection of differentiated memory B cells, the molecular mechanisms which regulate and control the transition of the virus through the various life cycle phases, and why IM is more common when infection occurs later in life.

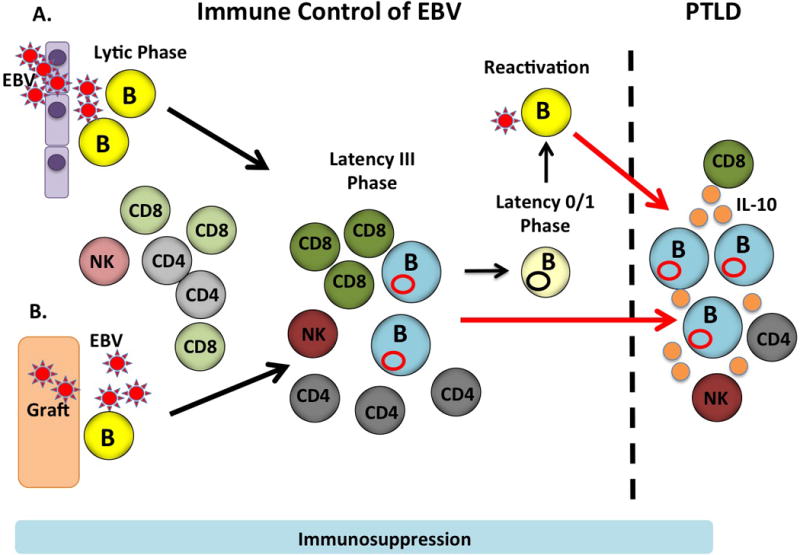

Figure 1. Host defense systems in transplant recipients during EBV infection and PTLD.

EBV transmission can occur A) in the community by entry through the oropharynx and/or B) via transplantation of a graft from an EBV+ donor. EBV establishes a productive lytic infection in which viral particles are produced and this process is targeted by NK cells (light orange) as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (light gray and light green, respectively) specific for lytic cycle proteins. EBV transitions to latency III and B cells harbor the virus as an episome (red circle) and acquire a lymphoblastoid like phenotype like the EBV+ B cell lymphomas in PTLD. However, the expansion of these B cells can be controlled by CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (dark gray and dark green, respectively) specific for latent cycle proteins as well as by NK cells (dark orange). Through processes that are not completely understand the infected B cells can then transition to a latency 0/1 state in memory B cells (light yellow). Intermittently viral reactivation may occur and in some cases this may lead to the development of PTLD (red arrow) or control of latency III lymphoblastoid cells may be lost leading to PTLD (red arrow). EBV+ B cell lymphomas produce IL-10 (orange circles) that may further modulate function of EBV-specific T cells.

EBV-encoded proteins as targets of the immune response in immunocompetent individuals

During the EBV life cycle an array of viral proteins are coordinately expressed by the infected B cell that can potentially be targeted by the adaptive immune response. The lytic cycle phase involves over 80 genes and is characterized by the successive expression of immediate early (IE), early (E), and late (L) stage genes that contribute to viral replication. Two IE genes, BZLF1 and BRLF1, encode transactivators that drive expression of the E genes and are critical for inducing the switch from latency to active viral production. Viral reactivation in latently infected B cells can be mimicked experimentally through a variety of methods including treatment with phorbol esters, sodium butyrate, or anti-Ig reagents that trigger the B cell receptor (BCR), leading to rapid expression of BZLF1 and BRLF1. The E stage genes are primarily responsible for viral DNA amplification while the L genes encode viral structural proteins.

In the latent cycle phase, viral particles are not produced. Instead the EBV genome persists as an episome in the nucleus of the B cell and can express 6 nuclear latent cycle proteins (EBV nuclear antigen-1 (EBNA1), EBNA-2, EBNA3ABC, EBNA-LP) and 3 latent membrane proteins (LMP1, LMP2A/B) along with EBER, a noncoding transcript and the BamH1 rightward transcripts (BART) that encompass a cluster of viral microRNA (miRNA). The latent cycle genes can be expressed in 3 distinct patterns corresponding to different latency programs, termed I (EBNA1), II (EBNA-1, LMP1, LMP2A/B) and III (EBNA-1, EBNA-2, EBNA-3ABC, LMP1, LMP2A/B, EBNA-LP). The various latency gene programs have significance both in the viral life cycle and in malignancies associated with EBV. During typical infection, it has been proposed that latency type III drives a growth program that is responsible for the lymphoblastoid-like characteristics of the latently-infected B cells that can expand in the tonsils and blood after primary infection. The latency II program has been proposed to promote survival of the infected naïve B cell through the germinal center reaction in the absence of encounter with antigen since 2 key viral proteins, LMP1 and LMP2 provide relevant signals; LMP2 mimics BCR signaling while LMP1 mimics CD40 signaling (12). In this way, the virus can take advantage of the normal B cell differentiation process to transition the viral genome into the long-lived memory B cells. At this point the infected B cell shifts to either latency I, or a 4th latency program, latency 0, in which no viral genes are expressed thereby enhancing the likelihood of immune escape. Interestingly, the latency gene programs expressed in normal, infected B cells are also replicated in the various malignancies associated with EBV. The latency I program is found in Burkitt’s lymphoma while the latency II gene expression pattern is found in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), an EBV-associated malignancy of epithelial origin. The features of the latency III type B cells are most like the EBV+ B cell lymphomas that arise in PTLD and in the lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL) that are generated in vitro by infection of normal B cells with laboratory strains of EBV. Together, these virally-encoded proteins serve a variety of functions in EBV infection, replication, transformation, growth, and survival of infected cells (13, 14) but here we focus on these proteins as potential targets of host immunity.

The T cell response to EBV

T cells dominant the landscape of immune protection against EBV (Fig. 1). Because primary infection with EBV is asymptomatic in most people and occurs early in life it has been difficult to study the dynamics of the immune response to EBV in the general population. On the other hand, we do have substantial information about the T cell response to primary EBV infection in immunocompetent individuals who develop IM (15). As noted earlier, IM is associated with a large expansion of activated CD8+ T cells in the circulation. Recent prospective studies of college students in which samples were collected prior to and after primary EBV infection demonstrated there is an extended incubation period after infection and the polyclonal expansion of T cells in the blood occurs around the time of the onset of symptoms (16). MHC class I/peptide tetramers have been used to definitively demonstrate that these cells are primarily CD8+ T cells specific for lytic cycle viral proteins, particularly immunodominant epitopes derived from 2 IE genes, BZLF1 and BMLF1 (17). In fact, the proportion of circulating CD8+ T cells directed against specific IE lytic protein epitopes in IM can be staggeringly high, approaching 50% in some cases (17). Collectively, a large number of studies over the past 20 years using ELISPOT and other in vitro T cell functional assays, along with MHC class I/peptide tetramers, suggest that of the lytic cycle proteins, epitopes from the IE genes, BZLF1 and BRLF1 appear to be immunodominant with CD8+ T cells directed at E lytic antigen-derived epitopes markedly less frequent (18). The L proteins, which are primarily structural components of the virus, elicit minimal CD8+ T cell response. Finally, CD8+ T cells specific for latent cycle proteins such as EBNA3, LMP2, EBNA1 and LMP1 can be detected, albeit at a much lower frequency than the immunodominant lytic epitopes. Of the latent cycle proteins, EBNA3 appears to be the most immunogenic for CD8+ T cells although exceptions have been identified (19). These general patterns of the hierarchy of lytic and latent cycle proteins in the CD8+ T cell response have been established across some HLA restriction elements. However, there is still much work to be done to create a comprehensive atlas of the relative responses of CD8+ T cells to EBV epitopes derived from the multitude of viral proteins in the context of specific HLA and across a broader swath of the human population.

In comparison, we know much less about the CD4+ T cell response to EBV because in IM, expansions of CD4+ T cells do not approach the magnitude seen with CD8+ T cells (20). In addition, tools for visualizing antigen specific CD4+ T cells, namely HLA class II/peptide tetramers, turned out to be much more difficult to produce and have only more recently become available. Early studies evaluated cytokine production from cells of healthy donors stimulated with peptide pools and found much lower frequency of responding CD4+ T cells compared to CD8+ T cells (21) with a broader distribution of lytic cycle and latent cycle proteins being immunogenic (22). Interestingly, the epitope hierarchy established for EBV-specific CD8+ T cells does not seem to be replicated in EBV-specific CD4+ T cells. For example, EBNA1 does not typically elicit a prominent CD8+ T cell response, but does induce a significant IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cell response in healthy EBV carriers on the order of 0.03% of circulating CD4+ T cells (23). HLA class II/peptide tetramer analysis of T cells in blood of IM patients showed that the CD4+ T cell response to EBNA1 is delayed, probably because the EBNA1 protein is not released from infected B cells, thus limiting T cell priming (24). However, early expansions of CD4+ T cells specific for other antigens, including EBNA2 and several lytic cycle proteins including L proteins, could be detected though the overall size of the response is still diminished compared to CD8+ T cells. These studies also suggest that, unlike CD8+ T cells, the CD4+ T cell response to latent cycle proteins may be greater than to lytic cycle proteins. This pattern seems to persist once disease has resolved and memory T cells have emerged. Thus, while the full picture is still emerging there are distinct differences in the magnitude, immunodominance, and breadth of the EBV-specific T cell response when comparing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. These factors are important when considering the use of ex vivo generated cytotoxic T cell lines for treatment of EBV disease including PTLD and for maximizing the efficacy of a potential EBV vaccine.

Humoral immunity to EBV

Evaluation of the humoral response to EBV has primarily focused on its diagnostic role and in the development of EBV vaccines. During natural infection, antibodies against the viral capsid antigen (VCA) appear 1st and probably play a role in viral neutralization. VCA is expressed late in the lytic phase of infection and in terms of the evolution of the adaptive immune response most likely follows earlier T cell responses to IE and some E antigens. Serologic testing for EBV represents the gold standard for assessing the status of exposure to the virus. Antibodies against lytic cycle proteins including VCA, gp350, a viral protein required for entry into B cells, early antigen-diffuse (EA-D) which is the product of the BMRF1 gene, and the latent cycle protein EBNA1 can be measured to help diagnose the presence or absence of infection and the stage of infection. IgM antibodies against viral structural proteins are indicative of a primary, acute infection, whereas IgG antibodies to VCA, arise later, can persist for life, and reflect a recent infection or infection in the past. Antibodies to EBNA, a latent cycle protein, tend to appear later after infection, persist for life and their presence indicates a prior infection, whereas EA-D IgG can suggest viral reactivation. Thus, evaluating the combined serostatus of these various antigens can help distinguish whether the individual has an early, primary infection, an ongoing active infection, a prior infection or even viral reactivation. Of course, in the setting of immunosuppression the development of these antibodies may lag or be altered, compared to their development in an immune competent individual, and may be outpaced by changes in viral copy number.

Natural killer cells and EBV

While the adaptive immune response to EBV has been extensively analyzed, only more recently has the role of the innate immune system (25), and natural killer (NK) cells in particular (26), been addressed. NK cells are lymphocytes of the innate immune system that possess the ability to rapidly recognize and respond to virally infected cells via cytotoxic pathways or production of immunomodulatory cytokines, hence they are viewed as an initial line of defense following infection. Key questions that are currently being pursued with respect to EBV are the relative roles of NK cells in controlling the lytic and latent phase of infection, the specific subsets of NK cells that participate in the various anatomical niches relevant to EBV, and which NK cell receptors and target cell ligands are involved in recognition and effector function against EBV-infected cells. Thus, our understanding of NK cells in EBV immunity is still emerging, but there are now a number of lines of evidence indicating that NK cells participate in controlling primary lytic infection (26). An expansion of the blood NK cell population has been noted in individuals with IM (15, 27) and in some cases, but not all, this correlated with decreased viral load levels (27). Studies in NOD-SCID mice reconstituted with human immune cells demonstrated that EBV infection triggered an increase in human NK cells in the blood. Conversely, depletion of NK cells resulted in increased viral titers and the development of EBV+ lymphomas because of the failure to control lytic infection (28). In addition, in vitro cytotoxicity assays demonstrate that human NK cells can kill EBV-infected B cells that have been induced to enter the lytic cycle; this was accompanied by downregulation of HLA class I molecules that bind to NK cell inhibitory receptors and upregulation of ligands that bind the NK cell-activating receptors NKG2D and DNAM-1 (29).

Indeed, NK cells are known to express a panoply of activating and inhibitory receptors on their surface and thus, a variety of NK cell subsets can be identified based upon the assortment of NK receptors that are expressed. A major goal in NK cell biology has been to identify specific NK cell receptors, and subsets that mediate recognition and activation of NK cells against virally-infected targets. Along these lines, it has been suggested that NKG2ChiCD57+ NK cells respond to CMV but not EBV (30, 31). However, Lunemann et al, (32) analyzed tonsils of EBV carriers and found a distinct NK cell population that is CD56brightNKG2A+CD94+CD54+CD62L− and can produce copious amounts of IFN-γ. When this NK cell subset is added to cultures of primary B cells infected with exogenous EBV, the rate of B cell transformation is decreased, compared to other tonsilar CD56bright NK cells suggesting the CD56brightNKG2A+CD94+CD54+CD62L− population may be particularly important in restricting malignant transformation of B cells. Azzi et al, (33) studied 22 pediatric patients diagnosed with IM and showed that early-differentiated CD56dim NKG2A+KIR- NK cells proliferate and preferentially expand in the blood during acute IM and persist for several months following primary, symptomatic infection. Moreover, co-culture of the CD56dim NKG2A+KIR- NK cells with lytically-infected B cells leads to CD107 mobilization in the NK cells, indicative of cytotoxic degranulation. While these studies identify NKG2A+ cells within the NK cell population response to EBV it is interesting to note that NKG2A is an NK cell inhibitory receptor, such that the role of this receptors remains to be established. Together these results suggest that the subpopulations of NK cells in the blood and in the tonsils, are distinct and that unique populations may be involved in controlling EBV during discrete stages of the viral life cycle (Fig.1). In addition, the specific activating receptor and corresponding ligand/s that mediate NK cell effector activity against EBV-infected cell is unknown. Finally, the role of NK cells in the latent phase of EBV infection, as in the context of EBV+ B cell associated PTLD, is still to be determined. Recent studies indicate that an NKG2A+2B4+CD16-NKG2C-NKG2D+ NK cell subset can mediate cytotoxicity against latently-infected, autologous LCL suggesting this subset could be a population of interest for NK-based therapies against EBV+ PTLD (34).

Viral strategies of immune evasion

EBV is a member of the herpes virus family that is well known for the “bag of tricks” these viruses employ to avoid the immune response and thereby augment viral persistence. Examples of immune evasion strategies utilized by EBV have been ascribed to both lytic and latent cycle gene products, as well as virally encoded miRNA, and can act at multiple levels including inhibition of the production of antiviral proteins, interference with antigen presentation by the infected cell, inhibition and modulation of the cell death pathways utilized by virus-specific effector T cells or NK cells, and production of molecules that dampen innate or adaptive immune cell function. The immune evasion tactics used by EBV have been recently reviewed (35) and will not be covered exhaustively here. Instead we will provide a few salient examples that are particularly relevant to transplantation and PTLD.

EBV encodes several proteins that can suppress the host immune response and a prominent example of this immune evasion strategy involves the cytokine IL-10. The gene product of lytic cycle protein BCRF1 is termed viral IL-10 (vIL-10) based on its homology to cellular IL-10 (cIL-10) and its immunomodulatory properties. vIL-10 can inhibit HLA-class I, ICAM, and B7 expression on human monocytes (36). PBMC infected with virus carrying a mutated form of BCRF1 had increased levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6 and TNF-β and increased cIL-10, suggesting that vIL-10 contributes to suppression of a proinflammatory cytokine environment (37). We have also shown that the latent cycle EBV gene LMP1 drives production of cIL-10 that may further impair the adaptive immune response directed against the virus (38) and potentially against the allograft (39). Interestingly, CD4+ T cells from EBV seropositive donors responding to the latent cycle protein LMP1 were shown to produce high levels of IL-10, similar to T regulatory 1 cells (40). This could, in part, contribute to the explanation of why LMP1 has been found to be 1 of the least immunogenic EBV proteins (18).

The antigen presentation pathway has also been targeted by EBV at multiple points and this could significantly affect the ability of CD4+ and CD8+ EBV-specific T cells to detect virally infected cells. Efficient elimination of EBV-infected B cells by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells requires recognition of viral peptides presented by MHC class I proteins expressed on the infected cell. The lytic cycle protein BNLF2a can interfere with loading of peptides to class I molecules in a unique manner. The transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) protein ordinarily facilitates translocation of peptides into the ER lumen, where they can be loaded onto MHC class I molecules for antigen presentation. The BNLF2a gene product inserts into the ER membrane (41) and associates with the core TAP complex to stabilize it in a transport-incompetent conformation, preventing peptide binding and translocation (42, 43). Other EBV-encoded genes including BGLF5 (44) and BILF1 (45) can act within the MHC class I presentation pathway to suppress expression and avoid CD8+ T cells recognition. The class II antigen presentation pathway, important in CD4+ T cell activity, has also been targeted by lytic cycle genes including BZLF1 (46) and BGLF5 (44). The BDLF3 late lytic cycle gene reduces both class I and class II expression through ubiquitination and proteasome-dependent degradation (47). Together, these tactics by the virus can promote immune evasion from host T cells. One consequence of reduced self-MHC expression is that virally-infected cells may become vulnerable to NK cell killing. Along these lines it is interesting to note that while BILF1 can inhibit class I expression (45), it appears to be restricted to HLA-A and –B alleles, while HLA-C is only modestly altered (48). Since HLA-C is a known ligand for NK cell inhibitory receptors this differential modulation of class I expression could suppress both T cell and NK cell killing. In addition, Williams et al, (49) have recently shown that the EBV-encoded molecule BHRF1, a viral Bcl-2 homologue, can protect EBV-infected cells from NK cell killing, possibly through its antiapoptotic properties. The innate immune response to EBV has also been targeted by BGLF5, which can downregulate TLR9, a sensor of EBV double stranded viral DNA, via RNA degradation (50). In addition to modulation of TLR expression EBV employs other maneuvers to impair the innate immune response including regulating the expression and function of interferon regulatory factors and type I interferon production (35, 51).

While the above studies primarily focus on immune evasion strategies elicited by lytic cycle genes, latent cycle genes can also suppress or subvert the host immune response to EBV. LCL generated with EBV strains deficient in LMP2A have increased resistance to CD8+ T cells specific for latent cycle genes compared to LCL generated with wild type EBV (52). LMP2A, as well as LMP1, contribute to transcriptional activation of Galectin-1 (Gal1), a carbohydrate binding protein, that is overexpressed in LCL and EBV+ PTLD tumors and that can trigger apoptosis of EBV-specific CTL (53). Earlier studies by our group showed that LMP1 interferes with Fas ligand mediated apoptosis of EBV+ PTLD cell lines by inhibition of caspase 8 activation and recruitment of cFLIP to the death inducing signaling complex (54). Recent studies also have shown that EBV+ LCL generated in the laboratory can act as “killer B cells” via the production and release of exosomes that contain FasL and can kill autologous CD4+ T cells (55).

Finally, EBV was the 1st human virus shown to encode miRNA (56), small noncoding RNA that participate in posttranscriptional gene regulation and are integral to a host of cellular processes including proliferation, survival, differentiation, and metabolism (57). We now know that viral miRNA can significantly impact the regulation of these processes in infected cells resulting in altered susceptibility to recognition and elimination by the immune system. By infecting B cells with EBV strains carrying either the full complement of viral miRNA genes, or lacking 13 EBV miRNA genes, it was shown that miRNA can interfere with antiviral CD4+ T cell and CD8+ T cell function on multiple levels including activation, IL-12 production and antigen presentation (58, 59). The BART region of the EBV genome encodes a miRNA cluster, several of which can target proapoptotic cellular proteins to inhibit apoptotic pathways in infected cells (60). These are some examples by which EBV miRNA can directly contribute to immune evasion. However, the virus can also coopt the host cell miRNA network to achieve similar effects. EBV infection significantly alters the cellular miRNA landscape of the infected B cells and can promote cIL-10 production by suppressing miR-194 in B cell lines derived from patients with PTLD (61). Together, these observations demonstrate that EBV employs myriad strategies to escape recognition and elimination by the immune system.

The immune response to EBV in transplant recipients and in PTLD

Most of the examples discussed above have come from experimental systems using cells from healthy, seropositive donors. Whether, and how, these viral immune evasion strategies operate in the setting of transplantation and PTLD is unclear. Our group addressed the fundamental question of whether EBV seronegative transplant recipients can generate a viral-specific T cell response against a primary infection using MHC class I/peptide tetramers (62). We found that CD8+ T cells against lytic and latent cycle antigens could be detected in the circulation within a few weeks’ posttransplant in previously uninfected recipients who had received a graft from an EBV+ donor. Moreover, the proportion of CD8+ T cells directed against these immunodominant antigens was similar to the levels measured in seropositive, immune competent individuals (17). In agreement with our findings, Pietersma et al, (63) followed the time course of the CD8+ T cell response to EBV in an EBV seronegative cardiac transplant recipient who received a graft from an EBV seropositive donor and found the emergence of an EBV-specific CD8+ T cell population within 24 days after the initial evidence of EBV infection. The number of EBV-specific T cells expanded upon viral reactivation and the cells were functional because they could produce IFN-γ in ELISPOT after stimulation with EBV-derived peptides. While these studies suggest that transplant recipients can mount a T cell response to primary EBV infection under the cover of immunosuppression, a key question remains as to the status of the T cell response to EBV in PTLD patients. The prevailing notion has been that either diminished numbers of EBV-specific T cells, and/or impaired function of EBV-specific T cells are key factors in the emergence of EBV+ B cell lymphomas in PTLD. Decreased numbers of EBV-reactive T cells based on IFN-γ production, in combination with increased EBV viral load, have been proposed as a predictive marker of PTLD (64). Wilsdorf et al, (65) analyzed 11 children with EBV+ PTLD and found the percentage of EBV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in PTLD patients, as measured by IFN-γ production in response to autologous EBV+ LCL, was not significantly different from the numbers of EBV-specific T cells in healthy controls or patients with EBV-reactivation. However, it is noteworthy that EBV-specific CD4+ T cells could not be detected by this methodology in more than half of the PTLD patients and in 1/3 of the healthy controls, and 3 of the PTLD patients had no detectable EBV-specific T cells at all. Polyfunctional T cells, which can simultaneously produce multiple cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2, have been noted in viral infections and it has been suggested that the presence of polyfunctional T cells is a better indicator of an effective response to a pathogen than single cytokine producing cells (66). Ning et al, identified polyfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells when PBMC of long-term EBV carriers were stimulated with peptide pools derived from latent and lytic cycle proteins. Two PTLD patients were included in the study and T cells from these individuals had diminished polyfunctionality with a distinct profile of no IFN-γ production, minimal IL-2 production, but strong TNF-α production and CD107 mobilization. Further, the pattern and hierarchy of EBV antigen immunodominance seen in the long-term carriers was not recapitulated in the PTLD patients raising the question of whether responses against specific EBV antigens or epitopes are more protective than others. This is particularly important in the context of vaccine design but also for harnessing the full potential of ex vivo adoptive CTL therapy for EBV+ PTLD (67). Along these lines, the latent cycle antigen EBNA1 elicited the expansion of specific effector T cells that produced IFN-γ and mobilized CD107 from PBMC of most of the PTLD patients. However, the antigen-specific CD4+ IFN-γ-producing T cells, but not the CD8+ IFN-γ-producing T cells were reduced in PTLD patients compared to healthy controls (68). Sequencing of the EBNA1 gene from the PTLD patient samples indicated most had a polymorphism within an EBNA1 epitope, such that when peptides containing the PTLD polymorphism were used to stimulate the T cells, the response was significantly greater. These results support the possibility that genetic diversity of the EBV genome at regions encoding immunogenic antigens may influence the magnitude of the T cell response to EBV and this will likely be an area of further investigation.

Chronic viral infections, as well as cancer, can lead to a state of T cell exhaustion in which antigen-specific T cells show impaired function and express inhibitory receptors such as PD-1 and Lag3 (69). This can result in failure to clear infection and has been demonstrated both in experimental animal models of infection and in humans with HIV, HCV infection, or EBV infection (70). The immunological status and prognosis of asymptomatic transplant recipients with long term increased levels of EBV after primary infection, termed chronic high viral load carriers, has been enigmatic (71). Gotoh et al, (72) found that the frequency of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells in chronic high viral load pediatric liver transplant recipients was not significantly different then the levels of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells in control transplant recipients. Pediatric thoracic organ recipients with chronic high viral load were found to have an increased proportion of CD8+ T cells specific for the lytic cycle antigen BZLF1 and the latent cycle antigen EBNA3A compared to patients with undetectable EBV loads (73). However, the EBV-specific CD8+ T cells from some, but not all, of the chronic high viral load carriers showed characteristics of an exhausted phenotype, based on expression of PD-1 and low levels of CD127. The EBV high viral load group also showed diminished IFN-γ release in response to EBV antigens. Moran et al, (74) found that PD-1 expression was increased on CD8+ T cells in the posttransplant period, compared to pretransplant samples, regardless of whether patients had high EBV loads or had previously resolved an EBV infection. Similarly, the cytokine response to EBV peptides by most CD8+ T cells in all 3 groups showed limited polyfunctionality, and was mainly characterized by a monofunctional IFN-γ response.

As discussed previously, there is emerging evidence that NK cells also play an important role in controlling EBV infection. Analysis of NK cells from PTLD patients showed they express higher levels of PD-1 and reduced levels of the natural cytotoxicity receptor, NKp46, and the activation receptor NKG2D, compared to NK cells from asymptomatic, EBV+ transplant recipients (75). Importantly, the direct analysis of clinical EBV+ PTLD specimens has revealed most contain PD-L1+ tumor cells, indicating the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway may be intact in PTLD (76). The regulation of PD-L1 expression has been examined in EBV+ B cells and it may have both viral and genetic components. Green et al, (77) identified an AP-1 responsive element in the PD-L1 gene and showed the EBV protein LMP1 can increase PD-L1 expression via the JAK/STAT pathway while a gain/amplification of chromosomal region 9p24.1, which includes the PD-L1 and PD-L2 genes, was found in 2 of 5 clinical EBV+ B cell PTLD specimens in another study (78). Collectively, these results suggest that inhibitory pathways may play an important role in impaired T cell responses in PTLD. At the same time, checkpoint inhibitor blockade in which antibodies or soluble proteins that interfere with ligand-receptor interactions of inhibitory pathways such as PD-1/PD-L1 or B7/CTLA4 have shown great promise in cancer immunotherapy. The observation that the PD1/PDL1 pathway is a putative target in EBV+ PTLD is of interest and the potential of this approach has been explored in experimental models. Using an EBV-infected human cord blood humanized mouse model of EBV+ B cell lymphomas it was shown that the B cell lymphomas that arise express PD-L1 and PD-L2, while the T cells express PD-1 and CTLA4 (79). Treatment of mice with anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD1 antibodies inhibited growth of EBV+ B cell lymphomas and this response was dependent upon the presence of T cells. Still to be determined is whether this strategy is effective in the setting of immunosuppression which would be beneficial for ongoing protection of the allograft, or whether immunosuppression must be halted to permit function of anti-EBV specific T cells.

Clearly, additional studies with larger patient cohorts are essential to fully elucidating the nature of the immune response to EBV in transplant recipients and in PTLD patients. Progress in this area would facilitate the identification of patients at risk for EBV+ PTLD, improve management of these patients, and offer new opportunities for effective therapies for EBV-associated malignancies.

Acknowledgments

OMM and SMK are funded in part by NIH R21 AI115313, R01 AI113130, R21 AI119686, UO1 AI104342, the Department of Defense, and the Transplant and Tissue Engineering Center of Excellence at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital.

Abbreviations

- BART

BamH1 A rightward transcripts

- BCR

B cell receptor

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- CyTOF

Cytometry time of flight

- cIL-10

cellular IL-10

- E

early

- EA-D

early antigen diffuse

- EBNA

Epstein Barr nuclear antigen

- EBV

Epstein Barr virus

- IE

immediate early

- IM

infectious mononucleosis

- L

late; miRNA

- LCL

lymphoblastoid cell lines

- LMP

latent membrane protein

- miRNA

microRNA

- NK

natural killer

- NPC

nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- PTLD

posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder

- TAP

transporter associated with antigen processing

- Treg

T regulatory cell

- VCA

viral capsid antigen

- vIL-10

viral IL-10

Footnotes

Authorship Information: OMM developed the article concept and researched the material; OMM and SMK wrote the article.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Swerdlow AJ, Campo E, Harris NO, et al. World health organization classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th. Vol. 2. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schober T, Framke T, Kreipe H, et al. Characteristics of early and late PTLD development in pediatric solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2013;95(1):240–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318277e344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dharnidharka VR, Webster AC, Martinez OM, Preiksaitis JK, Leblond V, Choquet S. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:15088. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor AL, Marcus R, Bradley JA. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) after solid organ transplantation. Crit Rev Oncol Hemat. 2005;56(1):155–67. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stojanova J, Caillard S, Rousseau A, Marquet P. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD): pharmacological, virological and other determinants. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gloghini A, Dolcetti R, Carbone A. Lymphomas occurring specifically in HIV-infected patients: from pathogenesis to pathology. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(6):457–67. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castillo JJ, Beltran BE, Miranda RN, Young KH, Chavez JC, Sotomayor EM. EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the elderly: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91(5):529–37. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen JI. Primary immunodeficiencies associated with EBV disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;390(Pt 1):241–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22822-8_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hislop AD, Taylor GS. T-Cell Responses to EBV. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;391:325–53. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22834-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan G, Miyashita EM, Yang B, Babcock GJ, Thorley-Lawson DA. Is EBV persistence in vivo a model for B cell homeostasis? Immunity. 1996;5(2):173–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80493-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fafi-Kremer S, Morand P, Brion JP, et al. Long-term shedding of infectious epstein-barr virus after infectious mononucleosis. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(6):985–9. doi: 10.1086/428097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thorley-Lawson DA. Epstein-Barr virus: exploiting the immune system. Nature Rev Immunol. 2001;1(1):75–82. doi: 10.1038/35095584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murata T. Regulation of Epstein-Barr virus reactivation from latency. Microbiol Immunol. 2014;58(6):307–17. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang MS, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus latent genes. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e131. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balfour HH, Jr, Odumade OA, Schmeling DO, et al. Behavioral, virologic, and immunologic factors associated with acquisition and severity of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection in university students. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(1):80–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunmire SK, Grimm JM, Schmeling DO, Balfour HH, Jr, Hogquist KA. The incubation period of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection: viral dynamics and immunologic events. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(12):e1005286. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callan MF, Tan L, Annels N, et al. Direct visualization of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during the primary immune response to Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J Exp Med. 1998;187(9):1395–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hislop AD, Taylor GS, Sauce D, Rickinson AB. Cellular responses to viral infection in humans: lessons from Epstein-Barr virus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:587–617. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blake N, Haigh T, Shaka’a G, Croom-Carter D, Rickinson A. The importance of exogenous antigen in priming the human CD8+ T cell response: lessons from the EBV nuclear antigen EBNA1. J Immunol. 2000;165(12):7078–87. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maini MK, Gudgeon N, Wedderburn LR, Rickinson AB, Beverley PC. Clonal expansions in acute EBV infection are detectable in the CD8 and not the CD4 subset and persist with a variable CD45 phenotype. J Immunol. 2000;165(10):5729–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amyes E, Hatton C, Montamat-Sicotte D, et al. Characterization of the CD4+ T cell response to Epstein-Barr virus during primary and persistent infection. J Exp Med. 2003;198(6):903–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long HM, Leese AM, Chagoury OL, et al. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cell responses to EBV contrast with CD8 responses in breadth of lytic cycle antigen choice and in lytic cycle recognition. J Immunol. 2011;187(1):92–101. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heller KN, Upshaw J, Seyoum B, Zebroski H, Munz C. Distinct memory CD4+ T-cell subsets mediate immune recognition of Epstein Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 in healthy virus carriers. Blood. 2007;109(3):1138–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long HM, Chagoury OL, Leese AM, et al. MHC II tetramers visualize human CD4+ T cell responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection and demonstrate atypical kinetics of the nuclear antigen EBNA1 response. J Exp Med. 2013;210(5):933–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunemann A, Rowe M, Nadal D. Innate Immune Recognition of EBV. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;391:265–87. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22834-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munz C. Role of human natural killer cells during Epstein-Barr virus infection. Crit Rev Immunol. 2014;34(6):501–7. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.2014012312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams H, McAulay K, Macsween KF, et al. The immune response to primary EBV infection: a role for natural killer cells. Br J Haematol. 2005;129(2):266–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chijioke O, Muller A, Feederle R, et al. Human natural killer cells prevent infectious mononucleosis features by targeting lytic epstein-barr virus infection. Cell Rep. 2013;5(6):1489–98. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pappworth IY, Wang EC, Rowe M. The switch from latent to productive infection in epstein-barr virus-infected B cells is associated with sensitization to NK cell killing. J Virol. 2007;81(2):474–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01777-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopez-Verges S, Milush JM, Schwartz BS, et al. Expansion of a unique CD57(+)NKG2Chi natural killer cell subset during acute human cytomegalovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(36):14725–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110900108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendricks DW, Balfour HH, Jr, Dunmire SK, Schmeling DO, Hogquist KA, Lanier LL. Cutting edge: NKG2C(hi)CD57+ NK cells respond specifically to acute infection with cytomegalovirus and not Epstein-Barr virus. J Immunol. 2014;192(10):4492–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lunemann A, Vanoaica LD, Azzi T, Nadal D, Munz C. A distinct subpopulation of human NK cells restricts B cell transformation by EBV. J Immunol. 2013;191(10):4989–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azzi T, Lunemann A, Murer A, et al. Role for early-differentiated natural killer cells in infectious mononucleosis. Blood. 2014;124(16):2533–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-553024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatton O, Strauss-Albee D, Zhao NQ, et al. NKG2A-expressing natural killer cells dominate the response to autologous lymphoblastoid cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus. Front Immunol. 2016;7:607. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ressing ME, van Gent M, Gram AM, Hooykaas MJ, Piersma SJ, Wiertz EJ. Immune evasion by Epstein-Barr virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;391:355–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22834-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salek-Ardakani S, Arrand JR, Mackett M. Epstein-Barr virus encoded interleukin-10 inhibits HLA-class I, ICAM-1, and B7 expression on human monocytes: implications for immune evasion by EBV. Virology. 2002;304(2):342–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jochum S, Moosmann A, Lang S, Hammerschmidt W, Zeidler R. The EBV immunoevasins vIL-10 and BNLF2a protect newly infected B cells from immune recognition and elimination. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(5):e1002704. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lambert SL, Martinez OM. Latent membrane protein 1 of EBV activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to induce production of IL-10. J Immunol. 2007;179(12):8225–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beatty PR, Krams SM, Martinez OM. Involvement of IL-10 in the autonomous growth of EBV-transformed B cell lines. J Immunol. 1997;158(9):4045–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall NA, Vickers MA, Barker RN. Regulatory T cells secreting IL-10 dominate the immune response to EBV latent membrane protein 1. J Immunol. 2003;170(12):6183–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horst D, Favaloro V, Vilardi F, et al. EBV protein BNLF2a exploits host tail-anchored protein integration machinery to inhibit TAP. J Immunol. 2011;186(6):3594–605. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hislop AD, Ressing ME, van Leeuwen D, et al. A CD8+ T cell immune evasion protein specific to Epstein-Barr virus and its close relatives in Old World primates. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1863–73. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wycisk AI, Lin J, Loch S, et al. Epstein-Barr viral BNLF2a protein hijacks the tail-anchored protein insertion machinery to block antigen processing by the tranpsort complex TAP. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(48):41402–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowe M, Glaunsinger B, van Leeuwen D, et al. Host shutoff during productive Epstein-Barr virus infection is mediated by BGLF5 and may contribute to immune evasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(9):3366–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611128104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zuo J, Currin A, Griffin BD, et al. The Epstein-Barr virus G-protein-coupled receptor contributes to immune evasion by targeting MHC class I molecules for degradation. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(1):e1000255. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li D, Qian L, Chen CG, et al. Down-regulation of MHC class II expression through inhibition of CIITA transcription by lytic transactivator Zta during Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. J Immunol. 2009;182(4):1799–809. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinn LL, Williams LR, White C, Forrest C, Zuo JM, Rowe M. The missing link in Epstein-Barr virus immune evasion: the BDLF3 gene induces ubiquitination and downregulation of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) and MHC-II. J Virol. 2016;90(1):356–67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02183-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffin BD, Gram AM, Mulder A, et al. EBV BILF1 evolved to downregulate cell surface display of a wide range of HLA class I molecules through their cytoplasmic tail. J Immunol. 2013;190(4):1672–84. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams LR, Quinn LL, Rowe M, Zuo JM. Induction of the lytic cycle sensitizes Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells to NK cell killing that is counteracted by virus-mediated NK cell evasion mechanisms in the late lytic cycle. J Virol. 2015;90(2):947–58. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01932-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Gent M, Griffin BD, Berkhoff EG, et al. EBV lytic-phase protein BGLF5 contributes to TLR9 downregulation during productive infection. J Immunol. 2011;186(3):1694–702. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ning S. Innate immune modulation in EBV infection. Herpesviridae. 2011;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2042-4280-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rancan C, Schirrmann L, Huls C, Zeidler R, Moosmann A. Latent membrane protein LMP2A impairs recognition of EBV-infected cells by CD8+T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(6):e1004906. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ouyang S, Juszczynski P, Rodig S, et al. Viral induction and targeted inhibition of galectin-1in EBV+ posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2016;117(16):4315–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-320481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Snow AL, Lambert SL, Natkunam Y, Esquivel CO, Krams SM, Martinez OM. EBV can protect latently infected B cell lymphomas from death receptor-induced apoptosis. J Immunol. 2006;177(5):3283–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klinker MW, Lizzio V, Reed TJ, Fox DA, Lundy SK. Human B cell-derived lymphoblastoid cell lines constitutively produce Fas ligand and secrete MHCII(+)FasL(+) killer exosomes. Front Immunol. 2014;5:144. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grasser FA, et al. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science. 2004;304(5671):734–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1096781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skalsky RL, Cullen BR. EBV noncoding RNAs. Curr Top Microbiol. 2015;391:181–217. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22834-1_6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tagawa T, Albanese M, Bouvet M, et al. Epstein-Barr viral miRNAs inhibit antiviral CD4(+) T cell responses targeting IL-12 and peptide processing. J Exp Med. 2016;213(10):2065–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Albanese M, Tagawa T, Bouvet M, et al. Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs reduce immune surveillance by virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(42):E6467–E75. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605884113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Piedade D, Azevedo-Pereira JM. The role of microRNAs in the pathogenesis of herpesvirus infection. Viruses. 2016;8(6) doi: 10.3390/v8060156. pii: E156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harris-Arnold A, Arnold CP, Schaffert S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus modulates host cell microRNA-194 to promote IL-10 production and B lymphoma cell survival. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(11):2814–24. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Falco DA, Nepomuceno RR, Krams SM, et al. Identification of Epstein-Barr virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in the circulation of pediatric transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2002;74(4):501–10. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200208270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pietersma FL, van Oosterom A, Ran L, et al. Adequate control of primary EBV infection and subsequent reactivations after cardiac transplantation in an EBV seronegative patient. Transpl Immunol. 2012;27(1):48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smets F, Latinne D, Bazin H, et al. Ratio between Epstein-Barr viral load and anti-Epstein-Barr virus specific T-cell response as a predictive marker of posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease. Transplantation. 2002;73(10):1603–10. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilsdorf N, Eiz-Vesper B, Henke-Gendo C, et al. EBV-Specific T-cell immunity in pediatric solid organ graft recipients with posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease. Transplantation. 2013;95(1):247–55. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318279968d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Appay V, van Lier RAW, Sallusto F, Roederer M. Phenotype and function of human T lymphocyte subsets: consensus and issues. Cytometry A. 2008;73a(11):975–83. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gottschalk S, Rooney CM. Adoptive T-cell immunotherapy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;391:427–54. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22834-1_15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jones K, Nourse JP, Morrison L, et al. Expansion of EBNA1-specific effector T cells in posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders. Blood. 2010;116(13):2245–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-274076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wherry EJ, Kurachi M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(8):486–99. doi: 10.1038/nri3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Petrovas C, Casazza JP, Brenchley JM, et al. PD-1 is a regulator of virus-specific CD8+ T cell survival in HIV infection. J Exp Med. 2006;203(10):2281–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Green M, Michaels MG. Epstein-Barr virus infection and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(Suppl 3):41–54. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12004. quiz 54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gotoh K, Ito Y, Ohta R, et al. Immunologic and virologic analyses in pediatric liver transplant recipients with chronic high Epstein-Barr virus loads. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(3):461–9. doi: 10.1086/653737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Macedo C, Webber SA, Donnenberg AD, Popescu I, Hua Y, Green M, et al. EBV-specific CD8+ T cells from asymptomatic pediatric thoracic transplant patients carrying chronic high EBV loads display contrasting features: activated phenotype and exhausted function. J Immunol. 2011;186(10):5854–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moran J, Dean J, De Oliveira A, et al. Increased levels of PD-1 expression on CD8 T cells in patients post-renal transplant irrespective of chronic high EBV viral load. Pediatr Transplant. 2013;17(8):806–14. doi: 10.1111/petr.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wiesmayr S, Webber SA, Macedo C, et al. Decreased NKp46 and NKG2D and elevated PD-1 are associated with altered NK-cell function in pediatric transplant patients with PTLD. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(2):541–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen BJ, Chapuy B, Jing OY, et al. PD-L1 expression is characteristic of a subset of aggressive B-cell lymphomas and virus-associated malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(13):3462–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Green MR, Rodig S, Juszczynski P, Ouyang J, Sinha P, O’Donnel E. Constitutive AP-1 activity and EBV infection induce PD-L1 in Hodgkin lymphomas and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders: implications for targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(6):1611–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ferreiro JF, Morscio J, Dierickx D, et al. EBV-positive and EBV-negative posttransplant diffuse large B cell lymphomas have distinct genomic and transcriptomic features. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(2):414–25. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ma SD, Xu XQ, Jones R, et al. PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade inhibits Epstein-Barr virus-induced lymphoma growth in a cord blood humanized-mouse model. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(5):e1005642. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]