Abstract

Background

Asian-Americans are a rapidly growing and diverse population. Prior research on dementia among Asian-Americans focused on Japanese-Americans or Asian-Americans overall, although marked differences in cardiometabolic conditions between subgroups have been documented.

Methods

We compared dementia incidence among four Asian-American subgroups (n=8,384 Chinese; n=4,478 Japanese; n=6,210 Filipino; n=197 South Asian) and whites (n=206,490) who were Kaiser Permanente Northern California members aged ≥64 years with no dementia diagnoses as of 1/1/2000. Dementia diagnoses were collected from medical records 1/1/2000–12/31/2013. Baseline medical utilization and comorbidities (diabetes, depression, hypertension, stroke, cardiovascular disease) were abstracted from medical records 1/1/1996–12/31/1999. We calculated age-standardized dementia incidence rates and Cox models adjusted for age, sex, medical utilization, and comorbidities.

Results

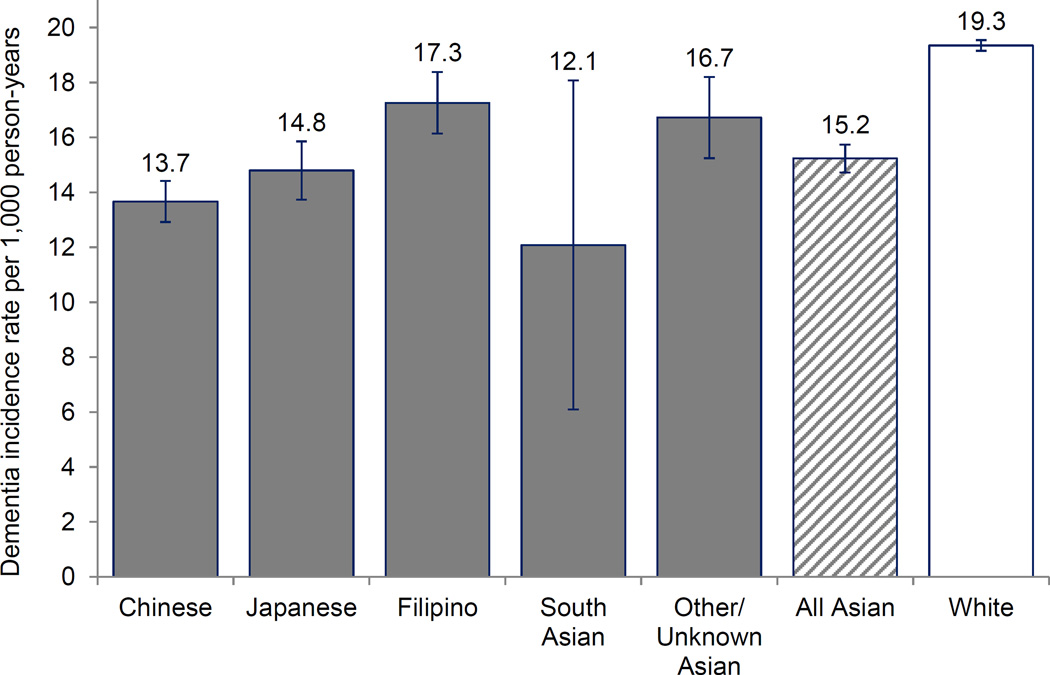

Mean baseline age was 71.7 years; mean follow-up was 9.6 years. Age-adjusted dementia incidence rates were higher among whites than “All Asian-Americans” or any subgroup. Compared with Chinese (13.7/1,000 person-years), dementia incidence was slightly higher among Japanese (14.8/1,000 person-years; covariate-adjusted-hazard ratio (adjusted-HR)=1.08; 95% CI=0.99–1.18) and Filipinos (17.3/1,000 person-years; adjusted-HR=1.20; 95% CI=1.11–1.31), and lower among South Asians (12.1/1,000 person-years; adjusted-HR=0.81; 95% CI=0.53–1.25).

Conclusions

Future studies are needed to understand how immigration history, social, environmental, and genetic factors contribute to dementia risk in the growing and diverse Asian-American population.

Keywords: dementia, race, ethnicity, disparities, epidemiology, cohort

Introduction

Asian Americans are a rapidly growing segment of the United States older population, and will constitute over 7% of adults over age 65 by 2050.1,2 Asian Americans are heterogeneous, with diverse immigration histories, cultural backgrounds, and socioeconomic exposures. Startling inequalities in cardiometabolic conditions have been documented between Asian American subgroups, including diabetes and coronary artery disease.3–10 For example, diabetes incidence rates were 14.7 per 1,000 person-years in Filipino American adults compared with 6.5 per 1,000 person-years in Chinese American adults in Kaiser Permanente Northern California.4 Given the associations between cardiometabolic health and dementia incidence,11–13 the inequalities in cardiometabolic health suggest that there may be parallel inequalities in dementia incidence between Asian American subgroups. Nonetheless, it is very challenging to study this heterogeneity because without intentional over-sampling, few studies include adequate representation of Asian Americans as a whole, let alone any Asian American subgroup, to provide informative estimates of dementia incidence.

Prior research on dementia among Asian Americans has focused on Japanese Americans or Asian Americans overall.14–18 Asian Americans are a diverse group, with Chinese, Filipinos, South Asians, as well as Japanese representing large proportions of the Asian American population.1 The prior research suggests that dementia incidence is lower among Japanese Americans and Asian Americans as a whole than among non-Latino whites.14–18 There is no evidence on whether similar patterns prevail for Chinese Americans (who comprise 23% of Asian Americans)19, Filipino Americans (20% of Asian Americans)19 or other Asian American subgroups. Evaluating the magnitude of heterogeneity in dementia rates across Asian American subgroups may lend insight into social, environmental, or genetic risk factors for dementia. Due to sample size limitations, many epidemiologic studies report data for Asian Americans as one group20,21 or enroll one subgroup of Asian Americans,9,14,16,22,23 and therefore cannot compare Asian American subgroups. Understanding the magnitude of heterogeneity is also important for evaluating the validity of and interpreting reports on Asian Americans overall. The objective of the present study was to evaluate 14-year dementia incidence among four Asian American subgroups (Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, South Asian) and non-Latino whites.

Methods

Study population

Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) is an integrated healthcare delivery system that provides comprehensive medical care to 3.8 million members (30% of the population in the geographic region). KPNC members are generally representative of the overall population of the geographic region, although people at extreme tails of the income distribution tend to be underrepresented.24–26 Older adults (age ≥65) included in the KPNC membership are similar to the general older adult population of the geographic region with respect to history of chronic conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and asthma, and lifestyle risk factors, including smoking, obesity, and sedentary behavior.26

Study design

We used data from a cohort of KPNC health plan members who were age ≥60 years and health plan members as of January 1, 1996, the year electronic medical records were introduced in the KPNC system. The present study includes health plan members who identified as Asian American or non-Latino white. Appendix Figure 1 describes the study flow. To ensure identification of dementia cases from time of first diagnosis, we applied a four year washout period from January 1, 1996 to December 31, 1999. At the end of the washout period, 280,147 people remained (a) alive, (b) health plan members, and (c) with no diagnosis of dementia. We excluded members missing race (n=5,682), those who identified as multi-racial (n=139), Black or African American (n=18,778), American Indian/Alaska Native (n=4,543), Latino (n=21,000), or Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (n=440). The final sample size includes n=23,032 Asian Americans and n=206,490 whites. These individuals were followed for up to 14 years for incident diagnosis of dementia. Participants were censored if they died, ended health plan membership (defined as a gap in membership ≥3 months), or were administratively censored if they were still alive, health plan members, and had no diagnosis of dementia as of December 31, 2013 (end of study period). The study was approved by the KPNC institutional review board, which waived the requirement for informed consent.

Measures

Race/ethnicity and Asian American subgroup

Self-reported race/ethnicity and Asian American subgroup identification were ascertained from KPNC health plan membership databases. The present study is restricted to health plan members who self-identified as non-Latino white (hereafter referred to as “white”) or Asian American. Asian American subgroups were categorized as Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, South Asian (Asian Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, or Nepalese), or Other/Unknown Asian. The “Other/Unknown” Asian group includes health plan members from subgroups with small numbers in the sample (e.g., Vietnamese or Korean), members who selected “other” for their Asian American ethnicity, and members for whom no information on Asian American subgroup was available.

Dementia

We used electronic medical records from inpatient and outpatient encounters between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2013 to identify new dementia diagnoses, based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnostic codes for Alzheimer’s disease (331.0), vascular dementia (290.4x), and nonspecific dementia (290.0, 290.1x, 290.2x, 290.3, 294.2x, 294.8), following our previous work.18,27–30 Medical history, physical examination, mental status examination, blood tests, functional ability, and neuroimaging data are usually used in the diagnosis of dementia in KPNC patients. Previous applications of this type of algorithm achieves sensitivity rates of 77–87% and specificity of 95% compared to consensus diagnoses.31 32 We did not include codes for frontotemporal dementia (331.1x), dementia with Lewy bodies (331.82), or Parkinson’s dementia (332.0+294.1x), in our definition of dementia. In combination, these three dementias had a cumulative incidence of <2% over the entire washout and follow-up period (January 1, 1996 to December 31, 2013).

Mortality

through December 31, 2013 was identified from the California State Mortality File, Social Security Death Records, or Kaiser Permanente electronic medical records. This method of mortality ascertainment has been used in previous studies of KPNCH health plan members.33,34

Covariates

We identified age and sex from KPNC health plan membership databases. We identified baseline characteristics, including medical utilization and comorbidities, during the dementia washout period of January 1, 1996 to December 31, 1999. As a measure of healthcare utilization, we calculated a dichotomous variable for whether the participant had ≥1 healthcare visit (inpatient or outpatient) per year during the 4-year washout period. We identified comorbidities, including diabetes, depression, hypertension, stroke (ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, and hemorrhagic stroke), and cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and peripheral arterial disease) based on inpatient and outpatient medical encounters using ICD-9 diagnostic codes (Appendix Table 1). KPNC records do not systematically record socioeconomic status.

American Community Survey information

Asian Americans have diverse immigration histories, but nativity (born in United States versus born outside of United States) was not available in the KPNC health plan records. To provide context on the size and socioeconomic characteristics of the older Asian American population in California, we analyzed publicly-available data from the 2010 American Community Survey, Integrative Public Use Microdata Sample files.35 For each Asian American subgroup, we examined proportion born in the United States versus born outside of the United States, proportion who speak only English at home (as a measure of acculturation), proportion with one or more years of college education, and proportion with a household income below the federal poverty line. The American Community Survey is a nationwide survey designed to complement the United States Census with detailed demographic, housing, economic, and social information about the United States population.36

Statistical Analysis

We summarized descriptive characteristics of the sample of KPNC health plan members, including mean baseline age, gender, mean follow-up time for dementia incidence, and baseline healthcare utilization and prevalence of comorbidities. We analyzed the 2010 American Community Survey, Integrative Public Use Microdata Sample files35 to summarize the population size and socioeconomic characteristics of the Asian American and Non-Latino white population age ≥65 of California in 2010.

Age-adjusted dementia incidence rates for each Asian American subgroup and non-Latino whites were estimated by standardization to the 2000 Census United States population. We estimated Cox proportional hazards models to facilitate covariate adjustment in comparing dementia risk between Asian American subgroups, using Chinese Americans as the reference group. Because of the strong association between age and incidence of dementia, we used age as the timescale, starting from age as of January 1, 2000 until age at dementia diagnosis, death, end of health plan membership (defined as a lapse in membership ≥3 months), or December 31, 2013 (end of study period). We first examined differences in dementia risk between Asian American subgroups with adjustment for age (as timescale) and sex (Model 1). Next, to account for potential differences in dementia diagnosis rates arising from unequal healthcare utilization, we additionally adjusted for healthcare utilization (≥1 annual healthcare visit) (Model 2). To examine whether proximal comorbidities could explain differences in dementia risk between Asian American subgroups, we additionally adjusted for comorbidities at baseline, including depression, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and cardiovascular disease (Model 3).

Results

At baseline, the mean ages of Asian Americans and whites were 71.7 years and 73.9 years, respectively (Table 1). Healthcare utilization was high overall: ≥78% of Asian American members had at least one healthcare visit per year throughout the 4-year washout period. Baseline prevalence of depression and stroke was low in all Asian American subgroups compared with whites. Prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease varied markedly across Asian American subgroups, with highest burden among Filipino Americans and South Asian Americans and lowest burden among Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans. The three largest Asian American subgroups represented in the current study (Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino) are also the three largest Asian American subgroups represented in the older adult population in California.37 Based on the 2010 American Community Survey,35 the proportion of foreign-born Asian Americans in California varies markedly across subgroups: the majority of older Japanese Americans in California were born in the United States (65%), while nearly all older Filipino Americans and South Asian Americans were born outside the United States (97% and 98%, respectively). Patterns of speaking only English language at home correspond with nativity patterns. Education at the level of at least one year of college was high among older Asian Americans overall in California, but was highest in Filipino Americans (60%), and lowest among the “other” Asian American group. Household poverty ranged from nearly 20% of Chinese Americans living in poverty compared with 7% of South Asian Americans.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample and American Community Survey information on Asian American population of California.

| Chinese | Japanese | Filipino | South Asian |

Other/ Unknown Asian |

All Asian American |

White | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaiser Permanente Northern California sample | |||||||

| N | 8,384 | 4,478 | 6,210 | 197 | 3,763 | 23,032 | 206,490 |

| Mean age at baseline (2000), years |

71.9 | 72.4 | 71.4 | 69.8 | 71.0 | 71.7 | 73.9 |

| Female, % | 48.3 | 63.9 | 54.0 | 26.9 | 50.7 | 53.1 | 54.9 |

| Mean years of follow-up for dementia incidence |

10.4 | 10.0 | 9.1 | 10.8 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 8.5 |

| Baseline utilization and health measures, estimated from 1996–1999 medical records | |||||||

| ≥1 healthcare visit per year, % |

81.4 | 78.7 | 78.8 | 85.8 | 73.3 | 78.9 | 82.3 |

| Depression, % | 5.7 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.1 | 6.6 | 5.5 | 11.6 |

| Diabetes, % | 29.0 | 29.8 | 41.4 | 43.2 | 33.9 | 33.5 | 21.3 |

| Stroke, % | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 8.5 |

| Hypertension, % | 50.8 | 49.3 | 62.3 | 51.8 | 51.8 | 53.8 | 49.9 |

| Cardiovascular disease, % | 14.5 | 14.4 | 20.0 | 31.5 | 18.9 | 16.8 | 24.1 |

| Myocardial infarction, % | 1.7 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.8 |

| Heart failure, % | 4.3 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 8.3 |

| Ischemic heart disease, % |

11.6 | 11.3 | 16.0 | 27.9 | 14.9 | 13.4 | 17.7 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, % |

2.6 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 6.8 |

| Characteristics of the ≥65 California population from the 2010 from the American Community Survey | |||||||

| N | 174,861 | 67,159 | 135,148 | 38,338 | 157,206 | 572,712 | 2,642,7 17 |

| Born in the United States, % |

10.2 | 64.7 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 12.6 | 86.9 |

| Speaks only English at home, % |

9.9 | 52.2 | 5.9 | 9.7 | 7.5 | 13.2 | 89.5 |

| Education: ≥1 year of college, % |

41.8 | 49.8 | 59.9 | 50.7 | 34.2 | 45.5 | 55.7 |

| Income below the federal poverty threshold, % |

18.1 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 6.8 | 18.3 | 14.3 | 9.2 |

Cardiovascular disease = peripheral arterial disease, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or ischemic heart disease.

Age-standardized dementia incidence rates varied across Asian American subgroups, but dementia incidence rates were lower in every Asian American subgroup than among whites (Figure 1, Table 2). Among the three largest Asian American subgroups, age-standardized rates were lowest among Chinese Americans (13.7 per 1,000 person-years), intermediate among Japanese Americans (14.8 per 1,000 person-years), and highest among Filipino Americans (17.3 per 1,000 person-years). Although the point estimate for dementia incidence was low for South Asian Americans, the estimate was imprecise because of the small number of South Asian Americans. Using the “All Asian American” incidence rate (15.2 per 1,000 person-years) instead of the subgroup-specific incidence rates underestimated incidence by 2.1 dementia cases per 1,000 person-years for Filipino Americans (whose subgroup specific rate was 17.3 per 1,000 person-years) but overestimated by 1.5 dementia cases per 1,000 person-years for Chinese Americans (whose subgroup specific rate was 13.7 per 1,000 person-years).

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted dementia incidence rates per 1,000 person-years estimated from 14 years of follow-up (Kaiser Permanente Northern California members, 2000–2013).

Table 2.

Dementia incidence rates over 14 years; age-standardized dementia incidence rates are presented graphically in Figure 1 (Kaiser Permanente Northern California members, 2000–2013).

| Number of events | Person-years | Unstandardized incidence rate (95% CI) | Age-standardized incidence rate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 1,398 | 87,100 | 16.05 (15.21, 16.89) | 13.67 (12.92,14.42) |

| Japanese | 842 | 44,979 | 18.72 (17.46, 19.98) | 14.80 (13.74,15.86) |

| Filipino | 1,029 | 56,743 | 18.13 (17.03, 19.24) | 17.26 (16.15,18.38) |

| South Asian | 21 | 2,133 | 9.85 (5.64,14.06) | 12.09 (6.10,18.07) |

| Unknown/Other Asian | 557 | 33,166 | 16.79 (15.40,18.19) | 16.73 (15.25,18.21) |

| All Asian American | 3,847 | 224,120 | 17.16 (16.62, 17.71) | 15.24 (14.73,15.74) |

| White | 45,110 | 1,750,252 | 25.77 (25.54, 26.01) | 19.35 (19.16,19.54) |

Differences in dementia risk between Asian American subgroups persisted after adjustment for age, sex, healthcare utilization, and comorbidities (Table 3). For example, dementia risk was approximately 10% higher among Japanese Americans compared with Chinese Americans, and approximately 20% higher among Filipino Americans compared with Chinese Americans.

Table 3.

Hazard ratios comparing dementia incidence by Asian American subgroup from Cox proportional hazards models (Kaiser Permanente Northern California members, 2000–2013).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Japanese | 1.08 (1.00, 1.18) | 1.09 (1.00, 1.19) | 1.08 (0.99, 1.18) |

| Filipino | 1.27 (1.17, 1.37) | 1.27 (1.17, 1.38) | 1.20 (1.11, 1.31) |

| South Asian | 0.88 (0.57, 1.35) | 0.87 (0.56, 1.33) | 0.81 (0.53, 1.25) |

| Other/Unknown Asian | 1.25 (1.13, 1.38) | 1.27 (1.15, 1.40) | 1.22 (1.10, 1.34) |

Model 1: adjusted for age (as timescale) and sex; Model 2: Model 1 + healthcare utilization (≥1 heathcare visit per year); Model 3: Model 2 + comorbidities (depression, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and CVD).

Discussion

In the first study to compare dementia incidence among Asian American subgroups, we found moderate differences in dementia incidence across subgroups in a large usual-care setting in Northern California. These differences remained after accounting for proximal vascular comorbidities. Dementia incidence was highest among Filipino Americans. Although we observed heterogeneity in dementia incidence between Asian American subgroups, incidence was lower in every subgroup than among whites.

Prior work on dementia incidence among Asian Americans has been limited to examining Asian Americans as one group or Japanese Americans alone. We previously reported that dementia incidence was lower among Asian Americans as a whole than among whites among Kaiser Permanente Northern California members (15.2 versus 19.4 per 1,000 person-years).18 To our knowledge, the only community-based cohort studies examining dementia prevalence or incidence among specific Asian American subgroups were conducted in the Kame Project—a cohort of older Japanese Americans in King County, Washington16,17 and the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study—a cohort of older Japanese American men living in Honolulu-Hawaii.14,15 Although neither of these studies included a white reference group, the dementia incidence rates in these studies suggested dementia incidence was similar or lower among Japanese Americans compared with whites in the United States. The Kame Project and Honolulu-Asia Aging Study are methodologically harmonized with the Adult Health Study cohort in Hiroshima Japan.38 These sister studies (collectively called the Ni-Hon-Sea Project) report similar dementia prevalence rates among older adults in Japan and Japanese Americans, although the proportion of cases attributed to Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia varied across studies.14–17,39,40 Additional cross-cultural studies of dementia incidence among Asian subgroups could help shed light on heterogeneity in dementia incidence among Asian Americans.

The 20% higher risk of dementia among Filipino Americans compared with Chinese Americans in the present study is similar in magnitude to the difference in dementia risk between whites and Asian Americans or Latinos and Asian Americans that we previously reported in this population.18 Several phenomena may contribute to heterogeneity in dementia risk between Asian American subgroups, and these can be conceptualized along a causal continuum. First, different Asian American subgroups have distinct immigration histories. The majority of Japanese Americans living in California were born in the United States, while the majority of Chinese Americans, Filipino Americans, and South Asian Americans were not. Recency of immigration is relevant for many reasons: people who choose to immigrate are often healthier than individuals who do not immigrate; the extremely complex and challenging process of moving countries may influence dementia risk; the years of exposure to U.S. culture may affect risk factors such as social integration, bilingualism, and obesity. Asian American subgroups may also have distinctive social and cultural traditions, such as dietary and exercise patterns, that affect dementia risk. Socioeconomic predictors of dementia, such as education, income, and occupational conditions, also differ on average between Asian American subgroups and may impact dementia risk differently than in other groups. Links between education and dementia—which are strongly inversely associated in most populations41—may not be the same for Asian Americans. Average level of education is lower among older Asian Americans overall than older whites in California, so the lower dementia in Asian Americans overall compared to whites is inconsistent with the overall educational patterns. Furthermore, Filipino Americans have the highest levels of education among Asian American subgroups but also the highest dementia incidence in our study. This surprising finding of higher dementia risk in a highly educated population may reflect differences in the quality of education, differences in the resources that education provides for Filipino Americans, or the education advantage may simply be overwhelmed by some risk factor that is more common in Filipino Americans. It is also possible that nonlinear associations between education and dementia may account for this observation, although we cannot explore this possibility in the current data. Finally, genetic variants linked to dementia, such as APOE-e4 genotype, may have different prevalence across Asian American subgroups. Although there are no national data on prevalence of APOE genotypes in Asian American subgroups, the HAAS,15 Kame,17 and MESA42 studies reported lower prevalence of APOE-e4 genotype in Japanese American and Chinese American participants compared with typical estimates for the U.S. population.11 All of these pathways may be partially mediated by known cardiometabolic risk factors, such as diabetes and obesity.

Our finding that dementia incidence is higher among Filipino Americans than other Asian American subgroups is consistent with patterns of cardiometabolic risk among Asian American subgroups.3–10 Our sample included too few South Asian Americans to produce precise estimates of dementia incidence rates, although South Asian Americans have been shown to have a high burden of cardiometabolic disorders.3–8,10 The Asian American patterns cannot be fully explained by differences in cardiometabolic conditions, however. Filipino Americans had lower dementia incidence than did non-Latino whites, despite higher cardiometabolic disease prevalence in Filipino Americans.

This study has some limitations. Although this study compares dementia incidence among multiple Asian American subgroups, Asian American subgroup was unknown for some health plan members, and some subgroups were too small to analyze separately (e.g., Vietnamese or Korean) or to obtain reliable estimates of dementia incidence rates (e.g., South Asians). This study relies on dementia diagnosis from medical records, and we could not reliably examine specific dementia subtypes (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease versus vascular dementia). Differences in healthcare utilization could contribute to differences in dementia diagnosis rates. However, healthcare utilization was high in all groups, and covariate-adjusted models were adjusted for healthcare utilization. That said, evaluating differential validity of diagnosis for Asian American subgroups remains an important area for future research. The present study does not distinguish between dementia subtypes (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease versus vascular dementia). Finally, the main objective of this study was to describe heterogeneity in dementia incidence. While we were able to examine the extent to which heterogeneity in dementia incidence remained after adjustment for proximal cardiovascular comorbidities, we were not able to account for lifecourse exposure to cardiovascular comorbidities, immigration history, including selection into immigration and immigrant generation, socioeconomic factors, or genetic factors, such as APOE genotype. Thus, the present study can only describe heterogeneity in dementia incidence among Asian American subgroups; it cannot identify the main factors contributing to the observed heterogeneity.

This is the first study to directly compare dementia incidence between Asian American subgroups; within the setting of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, we were able to follow 23,032 Asian Americans for 224,120 person-years. Despite the growing population of Asian Americans, there is a notable paucity of data sources available to evaluate the health profiles and risk factors for Asian Americans. Without designs that intentionally oversample Asian Americans, most studies do not include enough Asian Americans to support stratified analyses of Asian Americans as a whole, much less analyses of Asian American subgroups. The large size and diversity of the Asian American population, stability of membership, and long follow up enabled us to provide estimates of dementia incidence among Kaiser Permanente Northern California members. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California member population represents a usual-care setting, rather than a sample recruited from specialty clinics, making results more likely to be generalizable to the larger population of Asian Americans in Northern California. An important implication of our findings is that, despite the heterogeneity within Asian Americans, the overall pattern in comparison to whites was the same for each subgroup or when all Asian Americans were considered as a group. This suggests that likely heterogeneity of Asian Americans should not preclude examining Asian Americans as a group when data on Asian American subgroups are unavailable.

In a 14-year study of dementia incidence, we observed heterogeneity in dementia incidence between Asian American subgroups, with highest rates among Filipino Americans and lowest dementia incidence among Chinese Americans. However, dementia incidence was lower in every Asian American subgroup compared with whites. The present study describes heterogeneity in dementia incidence between Asian American subgroups. Future studies are needed to understand how immigration history, social, genetic, and environmental exposures contribute to dementia risk in this growing and diverse population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of support

This study was supported by National Institute on Aging grant numbers 1RF1AG052132 and 1K99AG053410; a grant from the Kaiser Community Benefits Health Policy and Disparities Research Program Foundation; a pilot grant from the University of California, San Francisco Center for Aging in Diverse Communities Scholar Program, part of the Resource Center on Minority Aging Research program funded by National Institute on Aging grant number 1P30AG15272; and by the National Institute Of Neurological Disorders And Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54NS081760.

References

- 1.Hoeffel E, Rastogi S, Kim M, Shahid H. The Asian Population 2010. Census 2010 Brief‥ US Census Bureau. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Proc. Economics and Statistics Administration, US Department of Commerce. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanaya AM, Herrington D, Vittinghoff E, et al. Understanding the high prevalence of diabetes in US south Asians compared with four racial/ethnic groups: the MASALA and MESA studies. Diabetes care. 2014;37(6):1621–1628. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karter AJ, Schillinger D, Adams AS, et al. Elevated rates of diabetes in Pacific Islanders and Asian subgroups: The Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE) Diabetes care. 2013 Mar;36(3):574–579. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holland AT, Wong EC, Lauderdale DS, Palaniappan LP. Spectrum of cardiovascular diseases in Asian-American racial/ethnic subgroups. Annals of epidemiology. 2011;21(8):608–614. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klatsky AL, Tekawa I, Armstrong MA, Sidney S. The risk of hospitalization for ischemic heart disease among Asian Americans in northern California. American journal of public health. 1994;84(10):1672–1675. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palaniappan LP, Araneta MRG, Assimes TL, et al. Call to action: cardiovascular disease in Asian Americans a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122(12):1242–1252. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181f22af4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JWR, Brancati FL, Yeh H-C. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Asians versus whites results from the United States National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2008. Diabetes care. 2011;34(2):353–357. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Araneta MRG, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. Type 2 Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome in Filipina-American Women A high-risk nonobese population. Diabetes care. 2002;25(3):494–499. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang EJ, Wong EC, Dixit AA, Fortmann SP, Linde RB, Palaniappan LP. Type 2 diabetes: identifying high risk Asian American subgroups in a clinical population. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2011;93(2):248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alzheimer's Association. 2016 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2016;12(4):459–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kloppenborg RP, van den Berg E, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ. Diabetes and other vascular risk factors for dementia: which factor matters most? A systematic review. European journal of pharmacology. 2008;585(1):97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sahathevan R, Brodtmann A, Donnan GA. Dementia, stroke, and vascular risk factors; a review. International Journal of Stroke. 2012;7(1):61–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White L, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, et al. Prevalence of dementia in older Japanese-American men in Hawaii: the Honolulu-Asia aging study. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276(12):955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havlik RJ, Izmirlian G, Petrovitch H, et al. APOE-epsilon4 predicts incident AD in Japanese-American men: the honolulu-asia aging study. Neurology. 2000 Apr 11;54(7):1526–1529. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.7.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graves AB, Larson EB, Edland SD, et al. Prevalence of dementia and its subtypes in the Japanese American population of King County, Washington state. The Kame Project. Am J Epidemiol. 1996 Oct 15;144(8):760–771. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borenstein AR, Wu Y, Bowen JD, et al. Incidence rates of dementia, Alzheimer disease, and vascular dementia in the Japanese American population in Seattle, WA: the Kame Project. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2014 Jan-Mar;28(1):23–29. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182a2e32f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayeda ER, Glymour MM, Quesenberry CP, Whitmer RA. Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimers & Dementia. 2016 Mar;12(3):216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Hasan S. The Asian population: 2010. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNeely MJ, Boyko EJ. Type 2 Diabetes Prevalence in Asian Americans Results of a national health survey. Diabetes care. 2004;27(1):66–69. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aoki Y, Yoon SS, Chong Y, Carroll MD. Hypertension, abnormal cholesterol, and high body mass index among non-Hispanic Asian adults: United States, 2011–2012. NCHS data brief. 2014;140:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bild DE, Detrano R, Peterson D, et al. Ethnic differences in coronary calcification the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Circulation. 2005;111(10):1313–1320. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157730.94423.4B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanaya AM, Kandula N, Herrington D, et al. Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study: objectives, methods, and cohort description. Clinical cardiology. 2013;36(12):713–720. doi: 10.1002/clc.22219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon NP, Kaplan GA. Some evidence refuting the HMO “favorable selection” hypothesis: the case of Kaiser Permanente. Advances in health economics and health services research. 1991;12:19–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. American journal of public health. 1992 May;82(5):703–710. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon NP. Similarity of the Kaiser Permanente Senior Member Population in Northern California to the Non-Kaiser Permanente Covered and General Population of Seniors in Northern California: Statistics from the 2009 California Health Interview Survey. Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research. 2012 Jan 6;2012 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitmer RA, Karter AJ, Yaffe K, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Selby JV. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009 Apr 15;301(15):1565–1572. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katon W, Lyles CR, Parker MM, Karter AJ, Huang ES, Whitmer RA. Association of depression with increased risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes and Aging Study. Archives of general psychiatry. 2012 Apr;69(4):410–417. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitmer R, Sidney S, Selby J, Johnston SC, Yaffe K. Midlife cardiovascular risk factors and risk of dementia in late life. Neurology. 2005;64(2):277–281. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149519.47454.F2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Exalto LG, Biessels GJ, Karter AJ, et al. Risk score for prediction of 10 year dementia risk in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a cohort study. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2013;1(3):183–190. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70048-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Williams LH, et al. Comorbid depression is associated with an increased risk of dementia diagnosis in patients with diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Journal of general internal medicine. 2010;25(5):423–429. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1248-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor DH, Fillenbaum GG, Ezell ME. The accuracy of medicare claims data in identifying Alzheimer's disease. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2002;55(9):929–937. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayeda ER, Karter AJ, Huang ES, Moffet HH, Haan MN, Whitmer RA. Racial/ethnic differences in dementia risk among older type 2 diabetic patients: the diabetes and aging study. Diabetes care. 2014 Apr;37(4):1009–1015. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang ES, Laiteerapong N, Liu JY, John PM, Moffet HH, Karter AJ. Rates of complications and mortality in older patients with diabetes mellitus: the diabetes and aging study. JAMA internal medicine. 2014 Feb 1;174(2):251–258. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruggles S, Genadek K, Goeken R, Grover J, Sobek M. In: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0 [Machine-readable database] University of Minnesota, editor. Minneapolis, MN: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS) [Accessed August 25, 2016]; www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/

- 37.U.S. Census Bureau. generated by Elizabeth Rose Mayeda; using American FactFinder. [Accessed August 15, 2016];2010 http://factfinder2.census.gov.

- 38.Larson EB, McCurry SM, Graves AB, et al. Standardization of the clinical diagnosis of the dementia syndrome and its subtypes in a cross-national study: the Ni-Hon-Sea experience. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998 Jul;53(4):M313–M319. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.4.m313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada M, Sasaki H, Mimori Y, et al. Prevalence and risks of dementia in the Japanese population: RERF's adult health study Hiroshima subjects. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47(2):189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb04577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamada M, Kasagi F, Mimori Y, Miyachi T, Ohshita T, Sasaki H. Incidence of dementia among atomic-bomb survivors--Radiation Effects Research Foundation Adult Health Study. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2009 Jun 15;281(1–2):11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Gamaldo AA, Teel A, Zonderman AB, Wang Y. Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC public health. 2014;14(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang S, Steffen LM, Steffen BT, et al. APOE genotype modifies the association between plasma omega-3 fatty acids and plasma lipids in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Atherosclerosis. 2013;228(1):181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.