Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis

NR4A1 was recently identified as an endogenous inhibitor of TGF-β-induced fibrosis and the role of this nuclear receptor has not been elucidated in tissue health or the response to injury in the vocal folds. Given the clinical implications of vocal fold fibrosis, we investigated NR4A1 expression during vocal fold wound healing in vivo and the regulatory roles of NR4A1 on vocal fold fibroblasts (VFFs) in vitro with the ultimate goal of developing targeted therapies for this challenging patient population.

Study Design

In vivo and in vitro

Methods

In vivo, the temporal pattern of NR4A1 mRNA expression was quantified following rat vocal fold injury. In vitro, the role of NR4A1 on TGF-β1-mediated transcription of genes underlying fibrosis as well as myofibroblast differentiation and collagen gel contraction was quantified in our human VFF line. Small interfering RNA was employed to alter NR4A1 expression to further elucidate this complex system.

Results

Nr4a1 mRNA increased 1 day after injury and peaked at 7 days. Knockdown of NR4A1 resulted in upregulation of COL1A1 and TGF-β1 with TGF-β1 stimulation (both p<0.001) in VFFs. NR4A1 knockdown also resulted in increased alpha smooth muscle actin positive cells (p=0.013) and contraction (p=0.002) in response to TGF-β1.

Conclusions

NR4A1 has not been described in vocal fold health or disease. Upregulation of TGF-β following vocal fold injury was concurrent with increased NR4A1 expression. These data provide a foundation for the development of therapeutic strategies given persistent TGF-β signaling in vocal fold fibrosis.

Level of Evidence

N/A

Keywords: Vocal fold, voice, fibrosis, NR4A1, nuclear receptor, transforming growth factor-β

INTRODUCTION

The etiology of fibrosis of the vocal folds (VF) is diverse. Following injury, healthy pliable tissue is replaced by fibrous scar resulting in aberrant vibratory function and intractable dysphonia.1 Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β has a wide range of biological functions and plays a critical, regulatory role in wound repair. Under normal physiological conditions, TGF-β transiently increases following injury to stimulate quiescent fibroblasts into activated myofibroblasts which express alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)2 which have contractile features and synthesize extracellular matrix (ECM), resulting in contraction and maturation of granulation tissue in early wound healing.3 Myofibroblast dedifferentiation and apoptosis typically occur as healing progresses to the more chronic stages. However, in fibrosis, exuberant TGF-β signaling sustains myofibroblast activation to continually synthesize ECM, resulting in aberrant architecture and function.4–6 Strategies to alter TGF-β signaling likely hold therapeutic promise for vocal fold fibrosis, a particularly challenging clinical entity.7,8

The development of physiologically-relevant therapeutics for fibrosis in general, and more specifically, VF scar requires increased insight into the biochemical mechanisms underlying these aberrant processes. Our group previously reported TGF-β signaling was Smad3-dependant in VF fibroblasts9 and RNA-based therapy to alter Smad3 expression may evolve into the clinical milieu to limit the TGF-β1-mediated pro-fibrotic phenotype.10,11 However, an alternative approach has evolved. Orphan nuclear receptor 4A1 (NR4A1, also known as NUR77, TR3, NGFI-B or NAK-I) belongs to the nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A (NR4A) which are implicated in multiple cell processes including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, metabolism, and development.12,13 NR4A receptors are rapidly induced across tissue systems, and NR4A1 has been implicated in metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurogenic diseases as well as arthritis, cancer, and other inflammatory and immunologic conditions.14 Recently, NR4A1 deficiency increased TGF-β signaling and exacerbated fibrosis in murine models of skin and lung fibrosis. Conversely, NR4A1 inhibited TGF-β signaling in mice overexpressing TGF-β receptor type I.15 Specifically, a NR4A1 agonist decreased TGF-β target gene expression including collagen, and limited experimentally-induced fibrosis. We hypothesize that NR4A1 is an ideal target to regulate intracellular TGF-β signaling, and ultimately, treat and/or avoid VF scar.

In the current study, we investigated the putative regulatory role of NR4A1 in VF injury and repair. Specifically, we sought to characterize the temporal dynamics of NR4A1 expression following VF injury and quantify the effects of altered NR4A1 signaling on downstream, TGF-β1-mediated transcriptional and regulatory pro-fibrotic events in VF fibroblasts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vivo

Vocal fold injury

The current protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the New York University School of Medicine. Thirty-six, 14 week old, female Sprague-Dawley rats underwent unilateral vocal fold injury as previously described.16 Briefly, following paralytic anesthesia via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (90 mg/kg) and xylazine hydrochloride (8 mg/kg), animals were placed on a custom operating platform in a near-vertical position and the larynx was visualized via 2.7mm, 0°or 30° telescope (Karl Storz, Flanders, NJ) coupled to a camera and video monitor. The right VF was injured by separating the lamina propria from thyroarythenoid muscle by inserting a 25-gauge needle at the lateral edge of right vocal fold. The lamina propria was then removed with microforceps. Six animals were randomized into seven experimental groups based on time of sacrifice: 0 (e.g., uninjured control), 1, 3, 7, 14, 30, and 90 days following injury. Following sacrifice, the larynx was harvested the bilateral vocal folds were dissected under magnification. Vocal folds from four animals were subjected to gene analysis and two were prepared for immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemistry

Upon harvest, the larynges were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for three hours and then in 30% sucrose for 24 hours at 4°C. After embedding in Optimum Cutting Temperature (O.C.T) formulation (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA), the samples were frozen and 10μm serial coronal sections were prepared. Sections including the mid portion of vocal folds were permiabilized and blocked with a solution containing 0.1% Triton-X and 5% normal goat serum, then incubated in primary rabbit monoclonal antibody against NR4A1 (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) overnight at room temperature. The slides were washed and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature and Alexa-Flour 555 anti-rabbit IgG (1:300; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was employed as the secondary antibody. Nuclei were counterstained by 4′, 6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). For negative controls, the primary antibodies were omitted. Stained sections were visualized and images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse Ni-U fluorescence microscope (Nikon Inc., Tokyo, Japan). All images were captured at 10x or 60x magnification.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the tissue via the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was reverse transcribed with a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) employed the TaqMan Gene Expression kit (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA) and StepOne Plus (Applied Biosystems). Taqman primer probes for Nr4a1 (Rn01533237_m1) and Gapdh (Rn01775763_m1) were employed. The ΔΔCt method was employed with Gapdh as the housekeeping gene.

In vitro

Cell culture

An immortalized human vocal fold fibroblast cell line created in our laboratory was employed for all in vitro experimentation. This cell line, referred to as HVOX, has been shown to be stable through multiple population doublings9; cells in passages 20–30 were used. Cells were cultured on 6-well plates in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic at 37°C under standard cell culture conditions. Following 12 hour serum starvation, HVOX were treated with serum-free DMEM + TGF-β1 (10ng/mL) and then harvested at appropriate time points to investigate the temporal dynamics of NR4A1 gene expression in response to TGF-β1 stimulation. Recombinant human TGF-β1 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was employed for cell stimulation.

Transfection

siRNA was then employed to knockdown NR4A1 expression. HVOX were transfected with 1pM of NR4A1 siRNA (Ambion, Grand Island, NY) in 2.5μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 6 hours. The transfection media was then replaced with fresh DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS; the cells were harvested every 24 hours for 96 hours to examine the duration of knockdown efficiency. Nonsense siRNA (Ambion) served as a control. In order to confirm effective NR4A1 knockdown, RNA extraction and quantification was performed as described previously and qRT-PCR was performed employing NR4A1 (Hs00374226_m1) and GAPDH (Hs02758991_g1) primer probes.

Gene analysis

After transfection, cells were cultured in complete media for 48 hours to recover the cell activity. After 12 hours starvation, cells were treated with serum-free DMEM + TGF-β1 (10ng/mL) and harvested at 4 or 24 hours. As described previously, qRT-PCR was then performed employing the following primer probes: NR4A1, SMAD2 (Hs00183425_m1), SMAD3 (Hs00969210_m1), SMAD7 (Hs00998193_m1), COL1A1 (Hs00164004_m1), SERPINE1 (Hs00167155_m1, TGF-β1 (Hs00998133_m1), and GAPDH.

Cell Staining

Transfected HVOX were grown on chamber slides for two days under each experimental condition. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and then permeabilized and blocked via a PBS solution containing 0.1% Triton-X and 5% normal goat serum. The slides were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary mouse monoclonal antibodies against αSMA (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich) and then the corresponding Alexa-Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500; Invitrogen) secondary antibody. Nuclei was counterstained with DAPI. Digital images were captured and both the total cell count and αSMA-positive cells were counted in ten randomly chosen, 3.0 mm2 fields for each condition under 10x magnification.

Collagen gel contraction

The gel contraction assay was performed according to our previous report11. Briefly, collagen gels were created using PureCol (Advanced BioMatrix, San Diego, CA) as previously reported17 using 0.5-inch Teflon rings. HVOX were gently pipetted onto gels at a concentration of 3.0x104 cells in 200μL complete media and incubated for 2 hours. The gels were then submerged in each media condition supplemented with 1% FBS. Gels were imaged at 0 and 12 hours using a digital 8-megapixel camera (Apple, Inc. Cupertino, CA). Contraction was quantified by measuring the gel area in pixels using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Percent contraction was then calculated via initial area–final area/initial area (%).

Statistical Analyses

For both in vivo and in vitro NR4A1 mRNA expression time course experiments, a one-way factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to determine a significant main effect, followed by Bonferroni/Dunn post-hoc comparisons to investigate differences in gene expression at each time point relative to control. For the remaining in vitro assays, a Student’s t-test was employed for two-group comparisons if the pretest for normality was not rejected at 0.05. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05; data are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD).

RESULTS

In vivo

Nr4a1 gene expression increased following vocal fold injury

Nr4a1 mRNA expression increased 1 day following injury (Figure 1A). This increase, however, did not achieve significance. Nr4a1 further increased three (p=0.021) and seven (p<0.001) days following injury with a return to baseline by 90 days, the endpoint of the current study. Immunohistochemical localization of NR4A1 expressing cells was performed. NR4A1 expressing cells emerged at one day following injury (Figure 1B). Positive cells were observed at the wound periphery three days following injury. By day seven, NR4A1 expressing cells were observed along the surface of lamina propria concurrent with epithelialization. Beyond seven days, limited NR4A1 expression was observed around the peripheral edge of injured site; NR4A1 expression decreased until 90 days.

Figure 1.

(A) Nr4a1 mRNA expression changes following rat vocal folds injury. Nr4a1 gene expression of injured right vocal fold increased from 1 day and reached at its peak level in 7 days, showing significant difference at 3 days and 7 days compared to control. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of assays run in triplicate (n=4; *p<0.05). (B) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for NR4A1. NR4A1 expressing cells emerged at 1 day following injury. Staining was observed in the peripheral edge of injured site at 3 days, and spread along the surface of lamina propria. NR4A1 expressions were gradually decreasing as time passed until 90 days, and returned to almost same appearance as uninjured vocal fold (day 0 control).Images were captured at x4 magnification or x60 magnification (the white boxed areas are shown magnified). Blue, DAPI; red NR4A1. Scale bar length is designated as in figures.

In vitro

TGF-β1 stimulated NR4A1 mRNA expression

The fundamental biological features of human vocal fold fibroblasts were investigated before proceeding to the further experimentation. As shown in Figure 2A, NR4A1 mRNA was upregulated under TGF-β1 stimulation; significantly increased NR4A1 expression was observed between one and eight hours, with peak expression at three hours (p<0.001). As shown in Figure 2B, NR4A1 gene expression was decreased by greater than 80% with siRNA; transfection efficiency was sustained for 96 hours after the transfection media was replaced with complete media (p<0.001 for all time points).

Figure 2.

(A) NR4A1 mRNA levels of human vocal fold fibroblasts (HVOX) under TGF-β1 stimulation in each time indicated. TGF-β1-mediated cells showed immediate-rapid reaction and highest upregulation at 3 hours. (B) Duration of siRNA NR4A1 (Si-NR4A1) efficacy on HVOX. NR4A1 mRNA levels were significantly reduced over 80% until 96 hours incubation in complete media following transfection. n≥4 for all; *p<0.05.

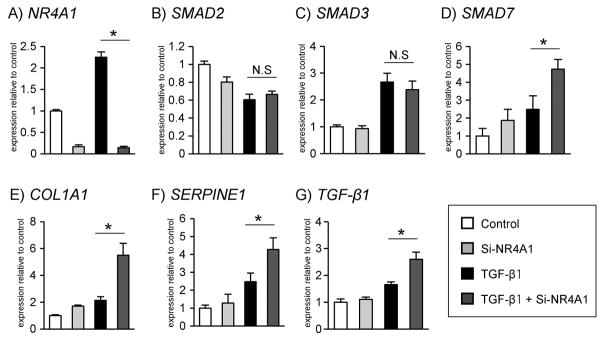

Decreased NR4A1 mRNA expression altered TGF-β1-mediated transcriptional events

Knockdown of NR4A1 mRNA expression was confirmed in TGF-β-stimulated cells at four hours (p<0.001; Figure 3A). At this time point, SMAD7 was significantly upregulated in the siRNA NR4A1 (Si-NR4A1) condition (p=0.002), whereas neither SMAD2 nor SMAD3 expression were affected by Si-NR4A1 under TGF-β stimulation (Figure 3B–3D). At 24 hours, COL1A1 and SERPINE1 were significantly upregulated in Si-NR4A1 transfected cells compared to control under TGF-β stimulation (p<0.001, p=0.004, respectively; Figure 3E, 3F). TGF-β1 mRNA expression also increased in response to NR4A1 knockdown (p<0.001; Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Effects of NR4A1 knockdown on gene expressions of TGF-β signaling. (D) SMAD7, (E) COL1A1, (F) SERPINE1, and (G) TGF-β1 mRNA of TGF-β-mediated HVOX showed upregulation in response to Si-NR4A1. n≥4 for all; *p<0.05.

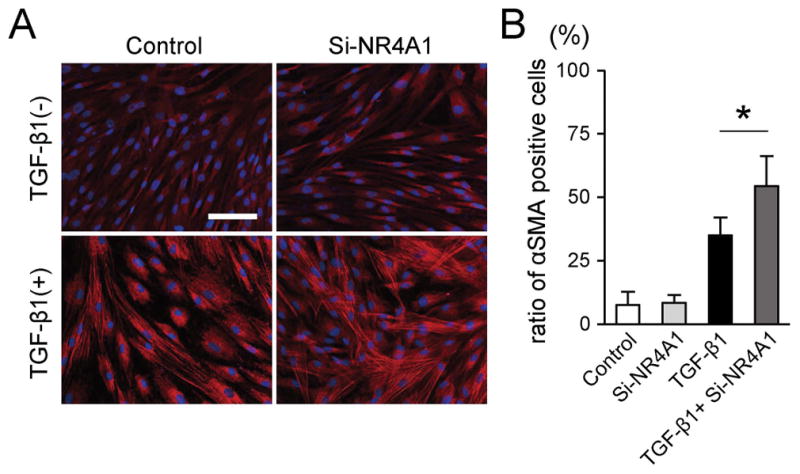

NR4A1 knockdown enhanced myofibroblast differentiation

As shown in Figure 4A, TGF-β1 stimulation appeared to alter both cell size and the appearance of stress fibers; increased αSMA expression was observed with NR4A1 knockdown. The ratio of αSMA-positive cells significantly increased in the Si-NR4A1 condition (p=0.013; Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of NR4A1 knockdown on cell phenotypic change into expressing αSMA. (A) Representative immunofluorescent images of HVOX under appropriate condition. Blue, DAPI; red αSMA. Scale bar: 100μm. (B) Ratio of αSMA-positive cells was calculated from 10 randomly chosen fields of four samples in each group. The ratio of αSMA-positive cells under TGF-β1 stimulation was significantly increased in Si-NR4A1. *p<0.05.

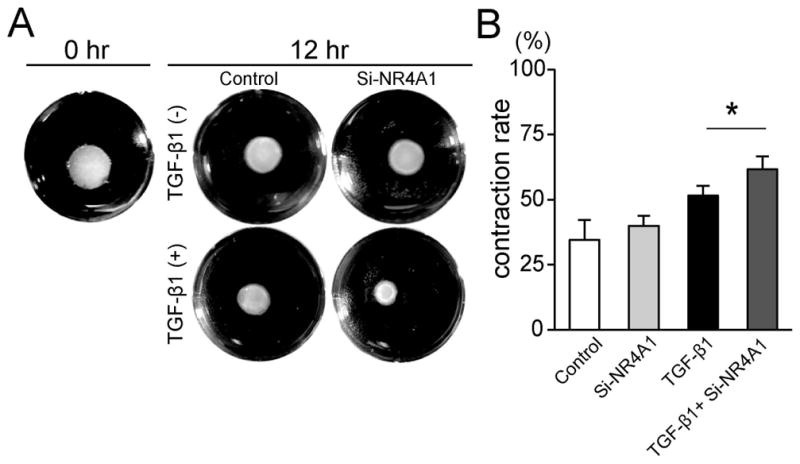

TGF-β-mediated collagen gel contraction was accelerated with knockdown of NR4A1

As shown in Figure 5A, stimulatory effects of TGF-β1 on gel contraction were observed, and this response accelerated with Si-NR4A1 knockdown (p=0.002; Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effects of NR4A1 knockdown on three-dimensional collagen gel contraction. (A) Representative gels under each culture condition directly after or 12 hours after cell seeding. Images were cropped along well periphery. (B) The stimulatory effects of TGF-β1 on contraction rate were significantly enhanced in Si-NR4A1. n=4 for all, *p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

The primary biological goal of the inherent tissue response to injury is regeneration of tissue. However, in the vocal folds and many other tissues, scar formation is both relatively common with significant clinical morbidity. Globally, excessive and/or sustained TGF-β presence in the wound milieu has been implicated in a variety of fibrotic disease processes.3 In the vocal folds, TGF-β transcription is observed as early as eight hours following injury18 and cell activation is maintained until chronic scar maturation.19 Direct therapeutic regulation of either TGF-β signaling or downstream antagonists of TGF-β are likely to ultimately hold significant clinical promise. In that regard, Palumbo-Zerr et al suggested that NR4A1 is an endogenous inhibitor of TGF-β. The dynamics of NR4A1 in vocal fold injury have not yet been described. Identifying key biochemical targets for intervention are particularly relevant given that the vocal folds are an ideal model for the direct application of therapeutics via in-office, awake procedures.

Nr4a1 mRNA expression increased from day 1 to day 30 following vocal fold injury, with significant upregulation between day 3 and day 7. This temporal pattern concurs with previous reports of TGF-β1 upregulation following vocal fold injury.20 Taken together with our in vitro data that NR4A1 upregulation was induced by short-term TGF-β1 stimulation, NR4A1 expression appears to be highly related to TGF-β1 metabolism following injury. With regard to localization, NR4A1 was observed in the epithelium at the peripheral edge of the wound site acutely, and thereafter, along the surface of the injury site one week following injury. Interestingly, Tateya et al previously reported re-epithelialization of injured rat vocal folds around one week after injury.16 Although not investigated, it is likely the re-epithelialization is highly related to migration and synthesis of neomatrix by the cells at the peripheral edge of the epithelial defect and further investigation is warranted to provide mechanistic insight into these processes and to provide optimal timing and/or location of treatments targeting NR4A1 in vivo.

Knockdown of NR4A1 induced upregulation of ECM genes, especially collagen encoding genes, and increased myofibroblast differentiation and contraction suggesting enhancement of the pro-fibrotic features of TGF-β-stimulated vocal fold fibroblasts. As secondary messengers of TGF-β stimuli, Smad2 and Smad3 expression were not affected by NR4A1 regulation. TGF-β1 was previously reported to stimulate Smad3-Smad4-SP1 complex binding to SP1 binding sites and promote downstream NR4A1 expression.15 Our data concur with these findings in that the Smad2/Smad3 complex is located upstream of NR4A1 and independent from NR4A1 manipulation.Smad7 upregulation with NR4A1 knockdown also concurs previous data; upregulation of Smad7 is thought to be anti-fibrotic as Smad7 is a competitive inhibitor of Smad3 heterodimerization. NR4A1 knockdown lead to enhanced myofibroblast differentiation and collagen contraction in response to TGF-β. Cumulatively, these data suggest the potential anti-fibrotic effects of NR4A1. However, the current study is not without limitation. In persistent TGF-β activation characteristic of fibrotic disease, phosphorylation of NR4A1 appears critical.15 As mentioned previously, NR4A1 transcription is regulated by Smad-SP1 complex, furthermore, NR4A1 itself recruits complexes that include SP1 and silence downstream TGF-β target genes, such as type I collagen. In contrast, phosphorylated NR4A1 cannot bind to SP1 thereby diminishing its role as a suppressor of TGF-β signaling. Further investigation is needed to clarify the relationship between phosphorylated NR4A1 and vocal fold fibroplasia.

Regardless, NR4A1 knockdown promoted and enhanced TGF-β-mediated pro-fibrotic features in vocal fold fibroblasts. And as such, activation of NR4A1 could be a promising candidate to suppress TGF-β signaling and exert a therapeutic effect on TGF-β-mediated fibrotic disease processes. In that regard, Cytosporone B (Csn-B) has a strong affinity for NR4A1 and has been shown to stimulate NR4A1 activation.21 Furthermore, Plumbo-Zerr et al reported that Csn-B ameliorated fibrosis in multiple experimentally-induced models of fibrosis including chronic/mature fibrosis.15 The vocal folds are an ideal model for novel, targeted therapeutics including Csn-B given their anatomical location for localized injection to avoid systemic side effects.

CONCLUSION

Globally, NR4A1 appears to be a potent regulator of TGF-β signaling across fibrotic conditions including the VFs. NR4A1 expression increased following vocal fold injury. In addition, knockdown of NR4A1 enhanced the pro-fibrotic effects of TGF-β stimulation in vocal fold fibroblasts including myofibroblast differentiation and contraction in addition to regulation of pro-fibrotic transcriptional events. These data provide a foundation for establishing novel strategies for targeting NR4A1 for vocal fold fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Deafness of and Other Communication Disorders (RO1 DC013277, PI-Branski)

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

REFERNCES

- 1.Benninger MS, Alessi D, Archer S, et al. Vocal fold scarring: current concepts and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;115:474–482. doi: 10.1177/019459989611500521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabbiani G, Ryan GB, Majne G. Presence of modified fibroblasts in granulation tissue and their possible role in wound contraction. Experientia. 1971;27:549–550. doi: 10.1007/BF02147594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinz B, Gabbiani G. Fibrosis: recent advances in myofibroblast biology and new therapeutic perspectives. F1000 biology reports. 2010;2:78. doi: 10.3410/B2-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phan SH. The myofibroblast in pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2002;122:286s–289s. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.286s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemoinne S, Cadoret A, El Mourabit H, Thabut D, Housset C. Origins and functions of liver myofibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeBleu VS, Taduri G, O’Connell J, et al. Origin and function of myofibroblasts in kidney fibrosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/nm.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hameedaldeen A, Liu J, Batres A, Graves GS, Graves DT. FOXO1, TGF-beta regulation and wound healing. International journal of molecular sciences. 2014;15:16257–16269. doi: 10.3390/ijms150916257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penn JW, Grobbelaar AO, Rolfe KJ. The role of the TGF-beta family in wound healing, burns and scarring: a review. International journal of burns and trauma. 2012;2:18–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Branski RC, Barbieri SS, Weksler BB, et al. Effects of transforming growth factor-beta1 on human vocal fold fibroblasts. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009;118:218–226. doi: 10.1177/000348940911800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paul BC, Rafii BY, Gandonu S, et al. Smad3: an emerging target for vocal fold fibrosis. The Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2327–2331. doi: 10.1002/lary.24723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branski RC, Bing R, Kraja I, Amin MR. The role of Smad3 in the fibrotic phenotype in human vocal fold fibroblasts. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:1151–1156. doi: 10.1002/lary.25673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.A unified nomenclature system for the nuclear receptor superfamily. Cell. 1999;97:161–163. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Germain P, Staels B, Dacquet C, Spedding M, Laudet V. Overview of nomenclature of nuclear receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:685–704. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safe S, Jin UH, Morpurgo B, Abudayyeh A, Singh M, Tjalkens RB. Nuclear receptor 4A (NR4A) family - orphans no more. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2016;157:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palumbo-Zerr K, Zerr P, Distler A, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor NR4A1 regulates transforming growth factor-beta signaling and fibrosis. Nat Med. 2015;21:150–158. doi: 10.1038/nm.3777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tateya T, Tateya I, Sohn JH, Bless DM. Histologic characterization of rat vocal fold scarring. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2005;114:183–191. doi: 10.1177/000348940511400303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parekh A, Sandulache VC, Lieb AS, Dohar JE, Hebda PA. Differential regulation of free-floating collagen gel contraction by human fetal and adult dermal fibroblasts in response to prostaglandin E2 mediated by an EP2/cAMP-dependent mechanism. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society. 2007;15:390–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2007.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim X, Tateya I, Tateya T, Munoz-Del-Rio A, Bless DM. Immediate inflammatory response and scar formation in wounded vocal folds. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2006;115:921–929. doi: 10.1177/000348940611501212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang Z, Kishimoto Y, Hasan A, Welham NV. TGF-beta3 modulates the inflammatory environment and reduces scar formation following vocal fold mucosal injury in rats. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:83–91. doi: 10.1242/dmm.013326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohno T, Hirano S, Rousseau B. Gene expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 and hepatocyte growth factor during wound healing of injured rat vocal fold. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:806–810. doi: 10.1002/lary.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhan Y, Du X, Chen H, et al. Cytosporone B is an agonist for nuclear orphan receptor Nur77. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:548–556. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]