Abstract

Objective

To provide effect size estimates of the impact of two cognitive rehabilitation interventions provided to patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI): computerized brain fitness exercise (BF) and memory support system (MSS), on support partners' outcomes of depression, anxiety, quality of life, and partner burden.

Methods

Randomized controlled pilot trial.

Results

At 6 months, the partners from both treatment groups showed stable to improved depression scores, while partners in an untreated control group showed worsening depression over six months. There were no statistically significant differences on anxiety, quality of life or burden outcomes in this small pilot trial; however, effect sizes were moderate suggesting the sample sizes in this pilot study were not adequate to detect statistical significance.

Conclusion

Either form of cognitive rehabilitation may help partners' mood, compared to providing no treatment. However, effect size estimates related to other partner outcomes (i.e., burden, quality of life, anxiety) suggest follow-up efficacy trials will need sample sizes of at least 30-100 people per group to accurately determine significance.

Keywords: Mild Cognitive Impairment, Caregivers, Behavioral Intervention, Cognitive rehabilitation

Caring for a loved one with dementia due to Alzheimer's disease (AD) can result in caregiver stress (e.g., Rabins et al., 1982). However, partners of those with earlier phases of decline, such as Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), can also experience distress and burden. Amnestic MCI involves measurable decline in memory with relatively retained functional abilities in daily life (Albert et al., 2011). Amnestic MCI is considered a risk state for later development of dementia due to AD.

Even if the impairments are relatively mild, the memory changes that occur in MCI can create increased burden for the care partner who may have to offer oversight of more complex daily responsibilities (Yueh-Feng & Haase, 2009). This may include increased supervision of finances, medications, scheduling appointments etc. (Ryan et al., 2010). Following a diagnosis, partners are faced with trying to cope with an uncertain future as to whether their loved one will progress from MCI to dementia.

Some MCI partners may experience depression and anxiety associated with caregiver burden (Garand et al., 2005). Memory problems, as well as mild changes in functioning, may interfere with relational abilities and cause relationship strain (Roberto et al., 2011). In addition, the partner may experience decreased participation in their own activities and interests (Werner et al., 2012).

There is currently no medical intervention that stops the progression from MCI to dementia. Behavioral interventions for MCI continue to be a key source of treatment. At this early stage, the person with MCI and their partner have an opportunity to develop self-management skills that may help improve quality of life for both (Yueh-Feng & Haase, 2012). For example, if the person with MCI is trained to use external memory supports (Greenway et al., 2008, 2012) they may be able to cue themselves to take their medication, remember an appointment, or complete a task independently. Our prior work using a specific system called the Memory Support System (MSS) showed that partners of individuals with MCI trained in the MSS had improved mood, while the partners of untrained individuals with MCI had declining mood and worsening of caregiver burden over time (Greenaway et al., 2012).

A variety of computer-based cognitive fitness programs built on the principles of positive brain plasticity and designed for use by older individuals are now commercially available. Research to date has shown that both participants with MCI, and cognitively normal older adults who trained on a Brain Fitness (BF) program showed an average a 1/3 standard deviation improvement on memory and cognitive function (Smith, et al., 2009; Barnes et al., 2009). It has not been evaluated if, and how, the partner is impacted if the person with MCI participates in cognitive fitness activities. If cognitive exercise helps the individual with MCI maintain cognition, then this may also decrease caregiver burden.

Overall, interventions that help with memory decline in persons with MCI may also help improve partner sense of burden, mood, anxiety, and quality of life. In this pilot study, we specifically compared two cognitive rehabilitation techniques, BF and MSS, in persons diagnosed with amnestic MCI. We aimed to estimate effect sizes for partner outcomes for the purpose of powering future efficacy trials of behavioral interventions in MCI, while providing some preliminary efficacy data.

Methods

Details of the interventions and recruitment have also been outlined in Locke et al. (2014).

Participants: Partners

A total of 200 consecutive dyads were approached across the three Mayo Clinic sites about study participation. 64 dyads passed eligibility screening, consented to participation, and were randomized to one of the two arms of the treatment protocol (MSS n =34, BF n =30). Partner enrollment criteria included:

Folstein Mini Mental Status Exam (Folstein et al., 1975) of 24 or greater to rule out significant cognitive impairment in the partners.

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D, Radloff, 1977) total score less than 21 to ensure that partners were free of severe depression suggesting more pressing need for psychiatric care.

English as primary language.

Seven dyads withdrew from the project prior to the start of any intervention. This report is based on the remaining partners/dyads (MSS = 30; BF = 27). Ninety six percent (55/57) of the dyads who began the study intervention completed the intervention phase. An additional eight dyads were lost at one of the post-program follow-up assessment time points. This report is focused on outcomes related to the partners in the program.

Participants: Patients with MCI

The outcomes for the patients with MCI are presented elsewhere (Chandler et al., under review), but a brief description of these patients is provided here to provide broad context to evaluate the partner outcomes. The patients were diagnosed with single or multi-domain MCI. Patient enrollment criteria included:

Dementia Rating Scale-2 (DRS-2, Jurica & Leitten, 2001) score ≥ 115

Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ, Pfeffer et al, 1982) score < 6

Not taking or stable on nootropic medications for at least three months.

There were no demographic differences between the treatment group patients in terms of age (M=75.3 years), education (M=16.2 years), gender (59% male), and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor use (55% stable on medication).

Control Sample

The control sample consisted of 20 dyads randomized to a no-treatment control group who were given the MSS materials without any training. There was no additional contact other than the follow-up assessment times. The control sample is the same as those reported in Greenaway et al. (2012).

Measures

The partners completed several self-report measures of mood, anxiety, quality of life, and burden at the following time points: pre-intervention baseline, training program completion, 3 month follow-up, 6 month follow-up, and one year follow-up. Control sample partners completed the measures at baseline, 3-months, 6-months, and one year.

Depression/Anxiety

Partners completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D) and the Anxiety Inventory Form (AIF), a 10-item rating scale modified from the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1983) by the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer's Caregiver Health project (Wisniewski et al., 2003). Scores for the CES-D range from 0 to 60, with higher scores suggesting more symptoms of depression. Scores for the AIF range from 10 to 40, with higher scores suggesting more symptoms of anxiety.

Quality of Life

The program partner completed the Quality of Life-AD (QOL-AD; Logsdon et al., 1999, Logsdon et al., 2006). Raw scores on the QOL-AD range from 13 to 52 with higher scores indicating better quality of life.

Caregiver Burden

Program partners completed the Caregiver Burden questionnaire (CB; Zarit & Zarit, 1990). Raw scores on the CB range from 0 to 88 with higher scores indicating more burden.

Interventions

Memory Support System (MSS)

The MSS is a two-page-per-day calendar and note-taking system small enough to fit in a pocket or handbag. The system and our training curriculum are described in detail in prior reports (Greenaway et al., 2008; Greenaway et al., 2012). The MSS training curriculum utilizes three training stages from learning theory outlined by Sohlberg and Mateer (1989). The partner's role in the training involves attendance at all training sessions, ongoing practice of the MSS techniques with the patient outside of the training sessions, and helping the patient complete the assigned homework. The partner also helps identify specific memory challenges that the patient is facing in daily life and helps the trainer set goals for development and individuation of the MSS materials. The partner also serves as an ongoing coach and trainer for use of the MSS after the formal training sessions have concluded.

Computer Training (Brain Fitness-BF)

Posit Science developed a computer-based training program, Brain Fitness (BF), built on the principles of positive brain plasticity and designed for use by older individuals (Barnes et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2009). The program is focused on speech reception to strengthen an individual's auditory memory with 6 modules: Hi-Lo, Tell Us Apart, Match It, Listen and Do, Sound Replay, and Story Teller. Those randomized to the computer training arm received copies of the MSS without training. Each dyad completed computer activities on the same schedule as those receiving MSS training. The partner's role was to complete all the computer exercises along with the patient.

Training Schedules

In addition to comparing these two cognitive rehabilitation interventions, we were also interested in evaluating different training schedules for each intervention. Each schedule provided 10 hours of intervention conducted either over 6 weeks or in 10 days. The 10-day condensed program involved one-hour sessions, 5 days per week for 2 weeks. The 6-week session involved twelve, 50-minute sessions over six weeks, starting with 3 per week for 2 weeks, then 2 per week for 2 weeks and then 1 session per week for two weeks. The final distribution of couples included the following: 6-week MSS n = 16; 6-week BF n = 14; 10-day MSS n = 18; 10-day BF n = 16.

Education

Because dementia education is readily available in the community, and if uncontrolled this may have “contaminated” our study, we provided such education to all the treated dyads. The BF and MSS dyads convened for an educational group lecture each day of the program. The control group did not receive this education. The education component is an adaption and synthesis of the Savvy Caregiver psychoeducational program (Hepburn et al., 2007) and the “Memory Club” educational program (Zarit et al., 2004; Gaugler et al., 2011). Topics included: Living with MCI, Changes in Roles and Relationships, Sleep Hygiene, Steps to Healthy Brain Aging, Preventing Dementia, MCI and Depression, Nutrition and Exercise, Assistive Technologies, Participating in Research, Safety Planning, and Community Resources.

Analysis

The primary aim for this study was evaluation of enrollment and retention patterns for such a behavioral trial. Those results are reported in Locke et al. (2014). Secondary aims, however, involved development of effect sizes for potential impact of these interventions on participant and partner outcomes for design of a larger scale clinical efficacy trial. This report details the partner outcomes.

The patient outcomes are fully outlined and discussed in Chandler et al., under review. To provide context for evaluation of the partner outcomes, brief patient outcomes are summarized here. Training in the use of the MSS calendar system significantly improved memory activities of daily living (ADLs) relative to standard care controls (d=.75, p=.01) while BF computerized training and receiving the MSS materials without training did not (d=.54, p>.05). Six weeks of MSS training may have the most impact on memory ADLs but sample sizes were too small for significance (d=.73 compared to 6 weeks of BF, p>.05). There were no statistically significant differences in self-efficacy but the effect size for MSS training compared to no treatment was moderate (d=.52, p>.05), while the effect size for BF computerized training compared to no treatment was small (d=.22, p>.05).

Repeated measures ANOVAs were utilized to compare total scores on partner outcome measures over time. Post-hoc ANOVAs were completed to evaluate group differences at each time in the event of a significant interaction term (group × time) in the repeated measures ANOVA. Comparisons between the intervention groups and the control group were limited to the six month follow-up period (due to attrition from the control group at one year). Comparisons limited to the intervention groups included the entire one year follow-up period. For this small pilot study, when the findings were non-significant, sample size calculations to achieve significance were made whenever at least a mild effect size or Cohen's d ≥ .20 was observed (Table 2).

Table 2. Change in Partner outcomes from baseline to 6 month follow-up.

| Change | Cohen's d Compared to Control | Cohen's d MSS vs BF | Significant at n of (per group) p<.05 / p<.01 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (CES-D) | ||||

| MSS (n=24) | ||||

| 6-week (n=11) | -3.1 (5.6) | 0.58 | 50/74 | |

| 10-day (n=13) | -.46 (4.9) | 0.11 | 131/195 | |

| Combined | -1.7 (5.2) | 1.05* | 0.35 | |

| BF (n=24) | ||||

| 6-week (n=12) | 0 (5.2) | 0.81* | ||

| 10-day (n=12) | 0 (3.8) | |||

| Combined | 0 (4.5) | |||

| Controls (n=14) | 3.8 (5.3) | |||

|

| ||||

| Anxiety (AIF) | ||||

| MSS (n=25) | ||||

| 6-week (n=12) | -.92 (5.5) | 0.46 | 0.23 | 294/434 |

| 10-day (n=13) | .31 (3.3) | 0.36 | 119/177 | |

| Combined | -.28 (4.4) | 0.01 | 76/112 (controls) | |

| BF (n=25) | ||||

| 6-week (n=12) | .25 (4.7) | 0.50 | 67/99 | |

| 10-day (n=13) | -.85 (3.1) | |||

| Combined | -.32 (3.9) | |||

| Controls (n=15) | 2.1 (6.4) | |||

|

| ||||

| Quality of Life (QOL) | ||||

| MSS (n=24) | ||||

| 6-week (n=12) | -1.2 (3.4) | 0.09 | 0.56 | 54/79 |

| 10-day (n=12) | -1.5 (3.5) | 0.03 | 135/200 (computer) | |

| Combined | -1.3 (3.4) | 0.35 | ||

| BF (n=25) | ||||

| 6-week (n=12) | -3.6 (5.2) | 0.27 | 250/372 | |

| 10-day (n=13) | -1.6 (2.9) | |||

| Combined | -2.6 (4.1) | |||

| Controls (n=15) | -1.6 (3.2) | |||

|

| ||||

| Burden (CB) | ||||

| MSS (n=24) | ||||

| 6-week (n=12) | -.67 (7.3) | 0.65 | 0.79 | 29/43 |

| 10-day (n=12) | -.41 (6.5) | 0.15 | 40/61 (controls) | |

| Combined | -.54 (6.8) | 0.32 | 163/240 (computer) | |

| BF (n=25) | ||||

| 6-week (n=12) | 4.5 (5.8) | 0.39 | 108/162 | |

| 10-day (n=13) | -1.3 (5.1) | |||

| Combined | 1.5 (6.1) | |||

| Controls (n=15) | 4.1 (7.7) | |||

Note: Utilized the subset of subjects included in the main repeated measures ANOVA. Negative scores represent improvement in depression, anxiety and burden, but decline in quality of life. For this small pilot study, when the findings were non-significant, sample size predictions to achieve significance at p<.05 and p<.01 were made for differences between groups that had at least a mild effect size (Cohen's d ≥ 0.2).

p < 0.05

Results

The majority of partners in the program were spouses (91%), while the remaining 9% were adult children of the person with MCI. The majority of partners were women (69%). The average partners' age was 70.2 (+12.5) years, education was 15.7 (+2.6) years, and Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) total score was 28.8 (+1.6).

At baseline, there were no significant differences between the MSS group and the BF group on demographics, mood, anxiety quality of life or burden measures (Table 1). However, the control partners were younger than the MSS partners (p=.02) and there was a trend for the control partners to also be younger than the BF partners (p=.09).

Table 1. Baseline values by program intervention group.

| MSS (n=30) |

BF (n=27) |

Controls (n=20) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partner Age | 72.9 (11.8) | 70.8 (10.4) | 65.5 (11.6) | .06 |

| Partner Education | 15.5 (2.6) | 15.6 (2.7) | -- | .75* |

| Partner Gender | 62% female | 76% female | 65% female | .42 |

| Partner Ethnicity | 91% white | 98% white | 80% white | .32 |

| Partner MMSE | 28.7 (1.7) | 29.2 (1.3) | 29.0 (1.1) | .51 |

| Partner CES-D | 7.5 (6.0) | 8.2 (7.6) | 7.0 (6.0) | .82 |

| Partner AIF | 16.9 (6.1) | 16.0 (4.8) | 16.9 (5.6) | .81 |

| Partner QOL | 44.0 (5.2) | 42.6 (6.9) | 41.4 (6.2) | .32 |

| Partner CB | 18.7 (10.7) | 20.6 (12.2) | 16.9 (10.3) | .53 |

p value from t-test comparison of treatment groups as data unavailable on control subjects.

Note. MMSE = Mini Mental Status Exam; CES-D = Center for Epidemological Studies-Depression Scale; AIF = Anxiety Inventory Form; QOL = Quality of Life; CB = Caregiver burden

Depression

Treatment groups compared to controls

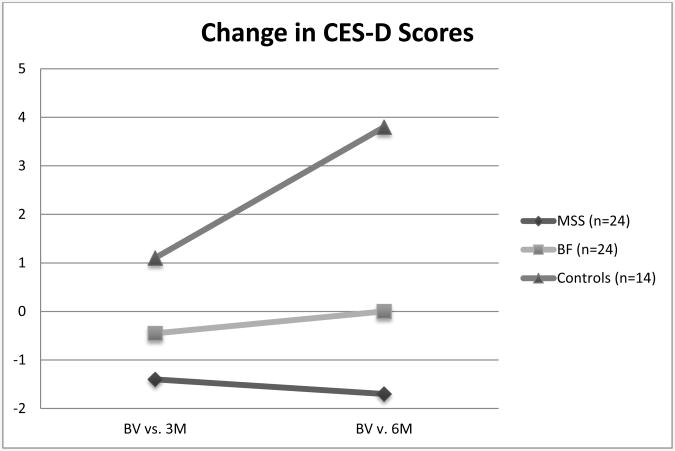

There was a significant interaction between treatment group and CES-D scores over 6 months [Wilks' Lambda (4,116) = 2.62, p=.04, η2p =.08]. Both treatment groups showed significantly different change over time at 6 months compared to the control group change (p=.002 and .03) but treatment group changes were not significantly different from one another (p=.24, Figure 1). The MSS group showed an average partner CES-D total score of 5.4 points and an average improvement from baseline (reduction in score) of 1.7 points at 6 months. The BF group showed an average partner CES-D total score of 8.9 with no change from baseline. The control group showed an average partner CES-D total score of 10.4 at 6 months with an average increase (worsening) in score of 3.8 points over 6 months (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Change in Partner CES-D Scores over time including control group.

Note: BV = baseline visit; 3M = 3 month visit; 6M = 6 month visit; MSS = memory support system; BF = brain fitness; Positive scores indicate increasing depression; Negative scores indicate decreasing depression

Treatment group comparison

Repeated measures ANOVA showed no statistically significant interaction between treatment group and CES-D scores over one year [Wilks' Lambda (4,35) = .49, p=.74, η2p =.05]

Treatment schedule comparison (between groups)

There was no significant change in partner CES-D scores at six months when comparing 6 weeks of MSS to 6 weeks of BF (p = .17) or when comparing 10 days of MSS to 10 days of BF (p=.80, See Table 2).

Treatment schedule comparison (within group)

There was no significant change in partner CES-D scores at six months when comparing 10 day and 6 week versions of the MSS treatment or when comparing 10 day and 6 week versions of the BF treatment (See Table 2). The effect size for CES-D change at 6 months when comparing 6 weeks vs. 10 days of the MSS treatment was d = .51 (CI: -2.80 to 3.17; Sample size requirement for significance = 61 subjects per group). The effect size for CES-D change at 6 months when comparing 6 weeks vs. 10 days of the BF treatment was d = 0 (CI: -2.94 to 2.15).

Anxiety

Treatment groups compared to controls

There was no significant interaction between group and AIF scores over 6 months [F(4,122) = .77, p=.55, η2p =.03].

Treatment group comparison

Repeated measures ANOVA showed no statistically significant interaction between treatment group and AIF scores over one year [F(4,36) = .191, p=.94, η2p=.02].

Treatment schedule comparison (between groups)

In comparing treatment groups with the same treatment schedule, there was no significant change in partner AIF scores at 6 months comparing the 6 week MSS and BF treatments (p=.58) or when comparing the 10 day MSS and BF treatments (p=.36, Table 2).

Treatment schedule comparison (within group)

There were no significant differences or trends in change in partner AIF scores over six months when comparing 10 day and 6 week versions of the MSS treatment or when comparing the 10 day and 6 week versions of the BF treatment (Table 2). The effect size estimate for AIF change at 6 months across treatment schedules for the MSS treatment was d = .28 (CI: -2.83 to 2.08; Sample size required for significance = 205 per group). The effect size estimate for AIF change at 6 months across treatment schedules for the BF treatment was d = .28 (CI: -2.37 to 1.97; Sample size required for significance = 199 per group).

QOL

Treatment groups compared to controls

There was no significant interaction between group and partner QOL scores over 6 months [F(4,120) = .497, p=.74, η2p =.02].

Treatment group comparison

There was no statistically significant interaction between treatment group and QOL scores over one year [F(4,37) = .187, p=.94, η2p=.02].

Treatment schedule (between groups)

In comparing treatment groups with the same treatment schedule, there was no significant change in partner QOL scores at 6 months comparing the 6 week MSS and BF treatments (p=.18) or when comparing the 10 day MSS and BF treatments (p=.93; Table 2.)

Treatment schedule comparison (within group)

There were no significant differences or trends in change in partner QOL scores over six months when comparing 10 day and 6 week versions of the MSS treatment or when comparing the 10 day and 6 week versions of the BF treatment (Table 2). The effect size estimate for QOL change at 6 months across treatment schedules for the MSS treatment was d = .09 (CI: -1.84 to 2.07). The effect size estimate for QOL change at 6 months across treatment schedule for the BF treatment was d = .58 (CI: -1.00 to 3.52; Sample size required for significance = 70 per group).

Burden

Treatment groups compared to controls

There was no significant interaction between group and partner burden scores over 6 months [F(4,120) = 1.073, p=.37, η2p =.04].

Treatment group comparison

There was no statistically significant interaction between treatment group and burden scores over one year [F(4,36) = .335, p=.85, η2p=.04].

Treatment schedule

In comparing treatment groups with the same treatment schedule, there was a trend for the 6 week MSS group to have stable to reduced burden at 6 months compared to increasing burden in the 6 week BF group (Table 2, p=.06, d=.79, CI: -2.49 to 4.92). The difference in change in burden across the 10 day treatment groups (MSS vs. BF) at 6 months was not significant (p=.71).

Treatment schedule comparison (within group)

There was no significant difference in change in partner burden scores when comparing 10 day and 6 week versions of the MSS treatment at six months (Table 2, d= .04, CI: -4.09 to 3.72). However, within the BF group, the 6 week group had significantly worsening caregiver burden at 6 months compared to baseline while the 10 day group had relatively stable or improved caregiver burden (Table 2, p=.01, d=1.07, CI: -2.21 to 3.84).

DISCUSSION

In these small samples, our results suggest that MSS or BF cognitive rehabilitation with a person who has MCI, and their support partner, positively impacts support partner depression scores over 6 months in comparison to a no-treatment control group. Specifically, the MSS group had the lowest depression scores with slight improvement over 6 months, the BF group remained stable over 6 months, and the control partners depression scores worsened over 6 months. This extends findings from Greenaway et al., 2012 which suggested worsening mood and increasing burden in an untreated control group in comparison to an MSS trained group only.

Interventions such as MSS and BF are primarily designed to impact cognitive symptoms in patients with MCI, but may also offer modest benefit on caregiver mood compared to no intervention at all. It is possible that the act of intervening alleviates distress regardless of the intervention mechanism. The MSS intervention appeared to have the larger effect size of the two treatments. We hypothesize that the patients with MCI in the MSS group had a memory compensation tool they could use instead of solely relying on their partner for information, which may have helped ease their partner's overall mood and burden more than brain fitness exercises or no treatment. In addition, at the completion of the MSS training process the partner is asked to become an active participant with the patient in use of the tool post-training. This active partnering involvement may also help reduce partner's depression and burden.

Our decision to provide treatment groups with caregiver education may confound our interpretation of results when comparing their outcomes with control group. Our historical control group did not have similar education intervention. Thus we cannot exclude that the education intervention alone may have accounted for these findings. The mechanism of benefit could be the knowledge developed from the educational topics, or the perceived social support via meeting together as a cohort each treatment session. However, it is reasonable to say that a multimodal intervention provided a positive impact on depression symptoms compared to no treatment.

The present study was funded as a pilot trial to primarily address recruitment and retention rates in a behavioral trial with MCI (Locke et al., 2014) and to estimate effect sizes for future trials. The effect sizes for depression, anxiety, and QOL measures seen for partners in these analyses are consistent with effect sizes observed for patient outcomes (Chandler, under review). Though some of these effects are modest, there are some medium effect sizes as well (i.e., anxiety and burden outcomes). These deserve further investigation especially in the absence of any current medical therapies to significantly alter the progression of amnestic MCI. These partner outcomes are predicted to be statistically significant only if our sample sizes ranged from 30-300 people per arm. In addition, treatment schedule comparisons suggest there may be a differential impact of an intervention when delivered over 6 weeks as compared to a compact 10 days. Finally, it is possible that there are interaction effects on partner outcomes that are dependent on patient outcomes or vice versa. Overall, larger scale trials are necessary to fully assess the efficacy of these types of interventions and optimal treatment schedule.

Key Points.

Providing patients with MCI cognitive rehabilitation interventions may decrease depression in a patient's care-partner over 6 months.

This small pilot study suggests the impacts on partner anxiety, quality of life, and caregiver burden are modest and larger trials will be necessary to detect statistical significance.

Effect size estimates suggest sample sizes of 30-100 per group would be needed to adequately power follow-up efficacy trials aimed at determining the impact on care partners of cognitive interventions in MCI.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by NINR (R01 NR012419) and PCORI (CER-1306-01897) for all sites. Additional Arizona support: NIA P30AG19610, NIA R01AG031581, and the Arizona Alzheimer's Research Consortium; Additional Mayo Clinic Rochester support: Mayo Alzheimer's Disease Research Center P50 AG16574; Additional Emory University support: Alzheimer's Associated NIRG-07-58843, Emory Alzheimer's Disease Research Center AG025688. REDCap database grant support UL1 TR000135.

Footnotes

We confirm that there are no known personal conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

References

- Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D, Yaffe K, Belfor N, Jaqust WJ, DeCarli C, et al. Computer-based cognitive training for mild cognitive impairment: results from a pilot randomized, controlled trial. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(3):205–210. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31819c6137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, Locke DEC, Duncan NL, Hannah S, Cuc A, Fields JA, et al. Computer versus compensatory training in mild cognitive impairment: functional impact. doi: 10.3390/brainsci7090112. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini-mental state. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatry Research. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garand L, Dew MA, Eazor LR, DeKosky ST, Reynolds CF. Caregiving burden and psychiatric morbidity in spouses of persons with mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20(6):512–522. doi: 10.1002/gps.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Gallagher-Winker K, Kehrberg K, Lunde AM, Marsolek CM, Ringham K, et al. The Memory Club: Providing support to persons with early-stage dementia and their care partners. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26(3):218–26. doi: 10.1177/1533317511399570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway MC, Hanna SM, Lepore SW, Smith GE. A behavioral rehabilitation intervention for amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2008;23(5):451–461. doi: 10.1177/1533317508320352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenaway MC, Duncan NL, Smith GE. The memory support system for mild cognitive impairment: randomized trial of a cognitive rehabilitation intervention. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;28(4):402–9. doi: 10.1002/gps.3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepburn K, Lewis M, Tornatore J, Sherman CW, Bremer KL. The Savvy Caregiver program: the demonstrated effectiveness of a transportable dementia caregiver psychoeducation program. J Gerontol Nurs. 2007;33(3):30–6. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20070301-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurica PJ, Leitten CL. Dementia Rating Scale-2: Professional Manual. 1st. Vol. 2001 Lutz, FL: PAR, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Locke DEC, Chandler Greenaway M, Duncan N, Fields JA, Cuc AV, Hoffman Snyder C, et al. A patient centered analysis of enrollment and retention in a randomized behavioral trial of two cognitive rehabilitation interventions in Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2014;1(3):143–150. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2014.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L. Quality of life in Alzheimer's disease: Patient and caregiver reports. J Ment Health Aging. 1999;5(1):21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH, Jr, et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982;37:323–329. doi: 10.1093/geronj/37.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabins P, Mace NL, Lucas MJ. The impact of dementia on the family. JAMA. 1982;248(3):333–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberto KA, Blieszner R, McCann BR, McPherson M. Family triad perceptions of mild cognitive impairment. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Sco Sci. 2011;66(6):756–768. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan KA, Weldon A, Huby NM, Persad C, Bhaumik AK, Heidebrink JL, et al. Caregiver support service needs for patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(2):171–176. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181aba90d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GE, Housen P, Yaffe K, Ruff R, Kennison RF, Mahncke HQ, et al. A cognitive training program based on principles of brain plasticity: results from the Improvement in Memory with Plasticity-based Adaptive Cognitive Training (IMPACT) study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(4):594–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohlberg MM, Mateer CA. Training use of compensatory memory books: a three stage behavioral approach. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1989;11(6):871–91. doi: 10.1080/01688638908400941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger DD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene PR, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. State -Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (STAIS-AD) Manual. Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Werner P. Mild cognitive impairment and caregiver burden: a critical review and research agenda. Public Health Reviews. 2012;34(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski SR, Belle SH, Coon DW, Markus SM, Ory MG, Burgio LD, et al. The resources for enhancing Alzheimer's caregiver health (REACH): Project design and baseline characteristics. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(3):375–384. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yueh-Feng YL, Zarit JE. Experience and perspectives of caregivers of spouse with mild cognitive impairment. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6(4):384–391. doi: 10.2174/156720509788929309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Femia EE, Watson J, Rice-Oeschger L, Kakos B. Memory Club: a group intervention for people with early-stage dementia and their care partners. Gerontologist. 2004;44:262–269. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit S, Zarit J. The memory and behavior problems checklist and the burden interview. Penn State: Gerontological Center, College of Health and Human Development; 1990. [Google Scholar]