Abstract

The vaginal microbiome plays an important role in maternal and neonatal health. Imbalances in this microbiota (dysbiosis) during pregnancy are associated with negative reproductive outcomes, such as pregnancy loss and preterm birth, but the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Consequently a comprehensive understanding of the baseline microbiome in healthy pregnancy is needed. We characterized the vaginal microbiomes of healthy pregnant women at 11–16 weeks of gestational age (n = 182) and compared them to those of non-pregnant women (n = 310). Profiles were created by pyrosequencing of the cpn60 universal target region. Microbiome profiles of pregnant women clustered into six Community State Types: I, II, III, IVC, IVD and V. Overall microbiome profiles could not be distinguished based on pregnancy status. However, the vaginal microbiomes of women with healthy ongoing pregnancies had lower richness and diversity, lower prevalence of Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma and higher bacterial load when compared to non-pregnant women. Lactobacillus abundance was also greater in the microbiomes of pregnant women with Lactobacillus-dominated CSTs in comparison with non-pregnant women. This study provides further information regarding characteristics of the vaginal microbiome of low-risk pregnant women, providing a baseline for forthcoming studies investigating the diagnostic potential of the microbiome for prediction of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Introduction

The complex microbial community present in the female lower genital tract is an important factor in a woman’s reproductive health. Imbalances in this microbiota can lead to bacterial vaginosis (BV), one of the most common gynaecologic conditions in women of reproductive age throughout the world1–3. At present, it is understood that the healthy vaginal microbiome is dominated by Lactobacillus species, while BV is characterized by a relatively low abundance of Lactobacillus spp. accompanied by polymicrobial anaerobic overgrowth, including species such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella spp., Bacteroides spp., Mobiluncus spp., and Mycoplasma hominis 4, 5.

In pregnancy, such imbalances in the vaginal microbiome are associated with an increased risk of post-abortal infection6, 7, early8, 9 and late miscarriage10, 11, histological chorioamnionitis12, 13, postpartum endometritis14, 15, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM)16, 17 and preterm birth18. The relationship between BV and preterm birth in particular has profound implications since children who are born prematurely have higher rates of cardiovascular disorders, respiratory distress syndrome, neurodevelopmental disabilities and learning difficulties compared with children born at term19, along with increased risk of chronic disease in adulthood20. Also, preterm birth complications are estimated to be responsible for 35% of the world’s annual neonatal deaths21.

The development of culture-independent techniques, such as high throughput DNA sequencing, has greatly facilitated the comprehension of the composition and role of the vaginal microbial community. These tools can be used to exploit the potential of the microbiome to diagnose BV-associated conditions. However, while most studies have focused on the vaginal microbiome of healthy, non-pregnant, reproductive aged women, relatively little is known about this microbiome in pregnancy. Pregnancy is associated with a variety of physiological events including increased sex steroid hormone levels22, host immune response modulation23, 24, altered immune-physicochemical properties of the cervical mucus25–27, as well as behavioural changes such as reduced drinking and smoking28. These factors may drive changes in the structure and/or composition of the microbial community resulting in a microbiome that is different from that of non-pregnant women. Thus, the current definition of a healthy microbiome, which has been based on findings in non-pregnant women, cannot necessarily be extrapolated to the microbiome in pregnancy. Establishing baseline data for the vaginal microbiome during pregnancy is a crucial step in the process of developing tools to predict and prevent pregnancy complications such as preterm birth, which is in turn associated with infection and/or inflammation as well as significant infant mortality and morbidity.

A few recent studies have used an amplicon sequencing approach to analyze the vaginal microbiome in pregnancy, all of which have been based on amplification and sequencing of variable regions of the 16 S rRNA gene. The results of these studies suggest that pregnancy has a marked effect on the vaginal microbiome, leading to greater stability, increased Lactobacillus proportional abundance and reduced richness and diversity relative to the vaginal microbiomes of non-pregnant women29–33.

The objectives of this study were to describe the vaginal microbiome of pregnant women at low risk for preterm birth and to compare their microbial profiles to those of healthy non-pregnant women34. This approach enabled direct comparisons between the two cohorts in which the main difference was their pregnancy status. Microbiome profiling was based on sequencing of the cpn60 universal target, which provides higher resolution than 16 S rRNA variable regions35 and has allowed us to resolve previously undescribed vaginal microbiome community state types34.

Results

Cohort description

Socio-demographic characteristics were comparable between pregnant and non-pregnant participants in terms of age, BMI, ethnicity and smoking status (Table 1). There was no significant difference in BMI (t-test, p = 0.211) or ethnicity (Chi-square, p = 0.372). However, pregnant women (age 33 ± 4) were on average older than non-pregnant women (age 31 ± 7) (t-test, p < 0.0001). The number of current smokers also differed between pregnant (2%) and non-pregnant women (12%) (t-test, p < 0.0001).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic, clinical and microbiological characteristics across pregnant and non-pregnant cohort.

| Characteristics | Pregnant | Non-pregnant |

|---|---|---|

| Age 1,* | (n = 182) | (n = 310) |

| (Mean ± SD, Range) | 33.6 ± 4.3 (21–45) | 30.1 ± 7.6 (18.6–49.2) |

| 18–25 | 5 (2.7%) | 111 (36%) |

| 26–35 | 122 (67%) | 131 (42%) |

| 36–49 | 55 (30.2%) | 68 (22%) |

| Body mass index 1 | (n = 182) | (n = 307) |

| (Mean ± SD, Range) | 23.1 ± 4.21 (17–43) | 23.9 ± 5.2 (15–50) |

| Underweight (<18.50) | 7 (3.8%) | 18 (5.8%) |

| Normal weight (18.51–24.9) | 140 (76.9%) | 194 (62.6%) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 26 (14.3%) | 55 (17.7%) |

| Obese (>30) | 9 (4.9%) | 40 (12.9%) |

| Ethnicity 2 | (n = 182) | (n = 306) |

| White | 117 (64.3%) | 200 (64.5%) |

| East Asian | 26 (14.3%) | 60 (19.4%) |

| South Asian | 13 (7.1%) | 12 (3.9%) |

| Black | 4 (2.2%) | 9 (2.9%) |

| Other/Mixed ethnicity | 22 (12%) | 25 (8%) |

| Smoking 2,* | (n = 182) | (n = 310) |

| Yes | 4 (2.2%) | 39 (12.6%) |

| Alcohol | (n = 182) | (n = 310) |

| Yes | 11 (6%) | no data |

| Unprotected sex 2,* | (in the past 4 days) | (in the past 2 days) |

| Yes | 47 (25.8%) | 45 (14.5%) |

| Nugent category 2,* | (n = 172) | (n = 307) |

| Not consistent with BV | 111 (61%) | 250 (80.6%) |

| Intermediate BV | 36 (20%) | 25 (8%) |

| Consistent with BV | 25 (14%) | 32 (10.3%) |

| CST 2,* | (n = 182) | (n = 310) |

| I | 56 (30.7%) | 156 (50.3%) |

| II | 12 (6.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| III | 30 (16.5%) | 50 (16.1%) |

| IVA | 0 (0%) | 36 (11.6%) |

| IVC | 26 (14.3%) | 22 (7.1%) |

| IVD | 42 (23.0%) | 24 (7.7%) |

| V | 16 (8.8%) | 22 (7.1%) |

| Estimated bacterial load (total copies of 16 S rRNA gene)/swab 1,* | (n = 181) | (n = 309) |

| (Mean ± SD, Range) | 7.77 ± 0.93 (4.89–10.67) | 6.83 ± 1.55 (3.50–10.31) |

| 104 or less | 1 (0.5%) | 47 (15.2%) |

| 105–106 | 27 (15%) | 97 (31.4%) |

| 107–108 | 133 (73.5%) | 146 (47.2%) |

| 109 or more | 20 (11%) | 19 (6.1%) |

| Presence of Mollicutes 2,* | (n = 182) | (n = 310) |

| Yes | 74 (40%) | 217 (70%) |

| Presence of Ureaplasma 2,* | 42 (23%) | 149 (48%) |

| U. parvum | 39 (21.4%) | 127 (41%) |

| U. urealyticum | 3 (1.6%) | 5 (1.6%) |

| Both | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) |

1t-test; 2Chi-square. *Characteristic with significant differences (at 5% level) between pregnant and non-pregnant cohorts.

Sixty-four percent of women described themselves as of Caucasian (white) background in the pregnant cohort, which was not different from the non-pregnant cohort. This was followed by East Asian (14%) and South Asian (7%). Ten percent of participants had other or mixed ethnicity. Pregnancy outcome data was not available for five women (5/182) since they delivered in different hospitals. Sixty women (33%) were nulliparous and the average gestational ages at enrolment and at delivery were 13+2 and 39+2 weeks, respectively (Table 2). Seventeen women (9.3%) had assisted conception and the majority of women had a vaginal delivery (74%) as opposed to C-section (26%). All infants were liveborn and seven were delivered prior to 37 weeks gestation. Average birth weight was 3376 g and only three newborns weighed less than 2500 g at birth, with one of these being preterm (<37 weeks gestation). Vaginal microbiomes from the women who delivered infants less than 2500 g were determined to belong to CST II (L. gasseri dominated) (1/3) and III (L. iners dominated) (2/3). Five infants were admitted to a level 3 intensive-care unit (NICU), four of which were preterm. None of these five infants had low birth weight. Vaginal microbiomes of the mothers of the five infants were determined to belong to CST III (L. iners dominated) (1/5), V (L. jensenii dominated) (2/5), IVC (G. vaginalis subgroup A dominated) (1/5) and IVD (mixed microbiome) (1/5).

Table 2.

Pregnant cohort description and pregnancy outcomes.

| Characteristics | Descriptive |

|---|---|

| Folic acid | (n = 182) |

| Before conception | 49 (26.9%) |

| During pregnancy | 50 (27.5%) |

| Vitamins | (n = 182) |

| Before conception | 100 (54.9%) |

| During pregnancy | 174 (95.6%) |

| Natural conception | (n = 182) |

| No | 18 (9.9%) |

| Parity | (n = 182) |

| 0 | 60 (33%) |

| 1 | 98 (53.8%) |

| 2–4 | 24 (13.2%) |

| Pre existing medical condition | (n = 182) |

| Hypo/Hyperthyroidism | 16 (8.8%) |

| Depression | 9 (4.9%) |

| Asthma | 6 (3.3%) |

| Anemia | 5 (2.7%) |

| Other condition | 41 (22.5%) |

| No | 105 (57.7%) |

| Surgeries in the past 10 years | (n = 182) |

| Yes | 83 (45.6%) |

| Antibiotics at enrolment (for other infections excluding vaginitis/BV) | (n = 182) |

| Amoxicillin/Penicillin | 8 (4.4%) |

| Nitrofurantoin | 3 (1.6%) |

| Other | 3 (1.6%) |

| Unknown/Unsure | 6 (3.3%) |

| No | 162 (89%) |

| Gestational age at enrollment | (n = 182) |

| (Mean ± SD, Range) | 13+2 ± 1+1 (11+1–16+6) |

| Gestational age at delivery | (n = 177) |

| (Mean ± SD, Range) | 39+2 ± 1+2 (32+1–41+2) |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | (n = 177) 7 (4%) |

| Mode of delivery | (n = 177) |

| Vaginal delivery | 131 (74.0%) |

| C-section | 46 (26%) |

| Fetal sex | (n = 177) |

| Female | 91 (51%) |

| Male | 86 (49%) |

| Birth weight (g) | (n = 177) |

| (Mean ± SD, Range) | 3376 ± 474 (1876–5200) |

| Low (<2500 g) | 3 (1.7%) |

| Normal (2500–4200 g) | 166 (93.8%) |

| Large (>4200 g) | 8 (4.5%) |

| Apgar score at 5 min | (n = 177) |

| (Mean ± SD, Range) | 8.97 ± 0.17 (8–9) |

| Neonate in level 3 care nursery after birth | (n = 176) 5 (2.8%) |

Sequencing results and OTU analysis

We characterized the vaginal microbiomes of pregnant women at low risk of preterm birth using pyrosequencing of the universal target region of the cpn60 gene. Sequence reads from the vaginal microbiomes of pregnant women were mapped on to a manually curated reference set of 1,561 OTU sequences as described in the methods. Raw sequence data files for the 182 samples described in this study were deposited to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (BioProject PRJNA317763). A total of 1,415,117 cpn60 reads was generated. Median and average read count per sample was 5,024 and 7,775 (range 494–43,245), respectively. Average read length was 448 bp. The average MAPQ value was 21.1.

Results of Bowtie2 mapping showed that these reads corresponded to 645 OTUs from the reference assembly (Supplementary Table S1). A total of 82 OTUs (corresponding to 53 nearest neighbour “species”) were at least 1% abundant in at least one sample. And only 22 “species” were detected in at least 50% of samples (Table 3). Although the ranges of percent identity to reference sequences are large in some cases, reflecting the diversity in the community, the most abundant OTU were at the high end of the range. In fact, of the 25 most abundant OTU in the study (accounting for 95% of the sequence reads generated), 22/25 were >95% identical to their nearest neighbour (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 3.

Prevalence and proportion of total reads for “species” detected in at least 50% of samples.

| Nearest neighboura | % OTU identity range | Prevalence/182 (%) | % total reads |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus jensenii | 81.6–100 | 181 (99.4) | 10.66 |

| Streptococcus devriesei | 83 | 180 (98.9) | 0.34 |

| Lactobacillus crispatus | 78.8–99.8 | 178 (97.8) | 31.93 |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | 91.8–100 | 178 (97.8) | 1.22 |

| Atopobium vaginae | 82.5–96.9 | 176 (96.7) | 1.62 |

| Weissella viridescens | 58.8–99.5 | 173 (95.0) | 0.22 |

| Desulfotalea psychrophila | 76.1 | 167 (91.7) | 0.12 |

| Lactobacillus iners | 86.8–100 | 165 (90.6) | 15.85 |

| Lactobacillus gasseri | 65.4–100 | 164 (90.1) | 5.69 |

| Streptococcus parasanguinis | 94.9–97.0 | 162 (89.0) | 0.08 |

| Prevotella tannerae | 77.5–98.7 | 162 (89.0) | 0.07 |

| Faecalibacterium cf. prausnitzii | 77.5–79.6 | 159 (87.3) | 0.16 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis subgroup C | 78.5–99.3 | 156 (85.7) | 4.45 |

| Peptoniphilus harei | 89.9–98.5 | 156 (85.7) | 0.07 |

| Clostridium innocuum | 75.4 | 148 (81.3) | 0.06 |

| Sphingobium yanoikuyae | 99.3–99.4 | 145 (79.6) | 0.08 |

| Eubacterium siraeum | 84.4 | 144 (79.1) | 0.05 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis subgroup B | 93.2–99.6 | 133 (73.0) | 0.54 |

| Massilia timonae | 82 | 126 (69.2) | 0.03 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis subgroup A | 86.7–99.6 | 123 (67.5) | 7.64 |

| Bifidobacterium breve | 89.6–99.5 | 119 (65.3) | 2.12 |

| Megasphaera sp. genomsp. type 1 | 58.1–86.7 | 112 (61.5) | 3.09 |

aClosest match in the cpnDB reference database based on sequence identity.

Most reads (68.8%) were identified as Lactobacillus spp. And only three OTUs, all of which matched to Lactobacillus spp., accounted for 55.7% of all reads generated: OTU 1403: L. crispatus (30.6%), OTU 1174: L. iners (15.4%) and OTU 1479: L. jensenii (9.7%). Species with the highest sample prevalence were L. jensenii (181/182), Streptococcus devriesei (180/182), L. crispatus (178/182), L. acidophilus (178/182), followed by Atopobium vaginae (176/182) and Weissella viridescens (173/182). Even though OTUs with similarity to Streptococcus devriesei and Weissella viridescens were detected in most samples, they had very low abundance, representing only 0.33% and 0.22% of all reads, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

Community state type analysis

Hierarchical clustering of vaginal microbiome profiles from pregnant women resulted in the resolution of six Community State Types (CST) (Fig. 1). All Lactobacillus-dominated CST, previously described by Ravel and Gajer36 based on pyrosequencing of the 16 S rRNA gene, were detected. Most profiles (114/182) were dominated by one of four Lactobacillus species that define four different CST: CST I (L. crispatus, n = 56), CST II (L. gasseri, n = 12), CST III (L. iners, n = 30), and CST V (L. jensenii, n = 16).

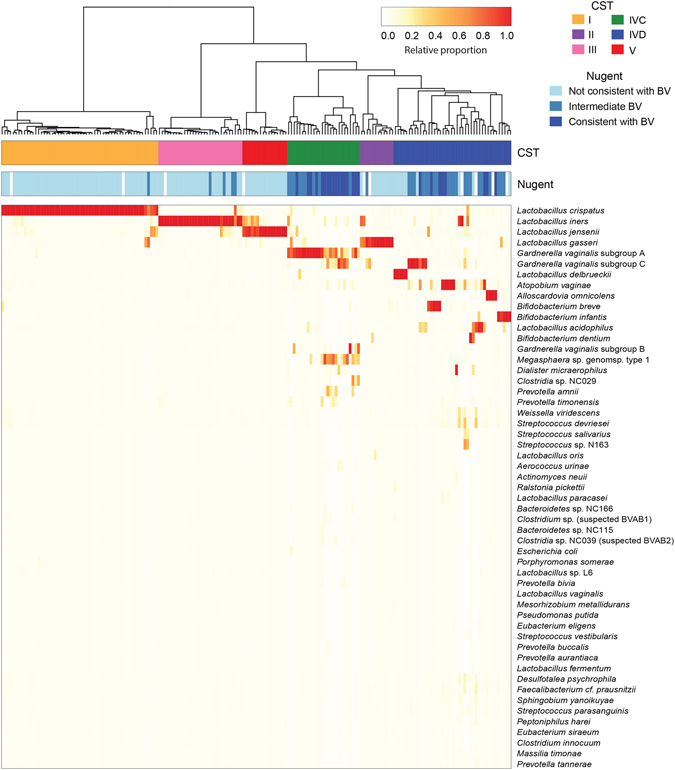

Figure 1.

Vaginal microbial profiles of pregnant women at low risk of preterm birth. Heatmap of hierarchical clustering of Jensen-Shannon distance matrices with Ward linkage on the relative proportions of reads for each OTU within individual vaginal samples (n = 182). Each column represents a woman’s vaginal microbiome profile, and each row represents an OTU. Only OTU that are at least 1% abundant in at least one sample are shown. The proportion of the total microbiome comprised is indicated by white to red colour according to the legend. The coloured bars above the heatmap show the community state type (CST) and the Nugent score category (Nugent) for each woman. Legend: white = missing data.

All non-Lactobacillus-dominated samples were assigned to CST IVC or CST IVD, as previously described by Albert et al.34. CST IVC (n = 26) is dominated by Gardnerella vaginalis subgroup A, Megasphaera sp. genomosp type 1, and G. vaginalis subgroup C. CST IVD (n = 42) was the most heterogeneous group, including a mixture of Bifidobacterium dentium, B. infantis, B. breve, L. delbrueckii, Alloscardovia omnicolens, G. vaginalis subgroup C, and Atopobium vaginae.

CST distribution of the pregnant participants was compared to the previously described non-pregnant cohort. Twelve pregnant women had microbiome profiles identified as the L. gasseri-dominated CST II, which was not observed among the profiles of non-pregnant women34. Additionally, CST IVA was not detected among pregnant women, including 61 with intermediate or high Nugent scores. In the non-pregnant group, 14/57 (24.6%) of women with intermediate or high Nugent scores were assigned to CST IVA, with the remainder in CST IVC (15/57, 26.3%), CST IVD (20/57, 35.1%) or one of the Lactobacillus dominated CST (8/57, 14.0%). CST IVA was defined by Albert et al.34 as a very heterogeneous group, dominated by G. vaginalis subgroup B or Atopobium vaginae, or combinations of Stapylococcus, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Alloscardovia, Gardnerella, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

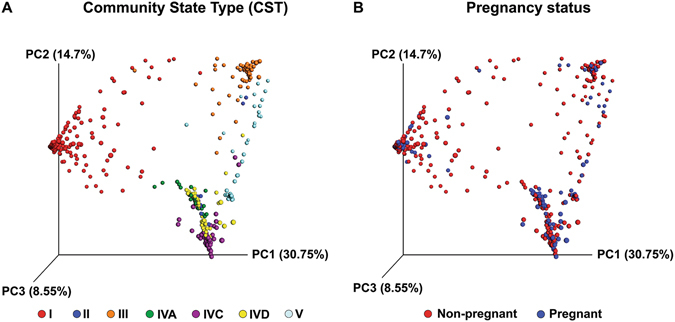

As expected, Lactobacillus-dominated CST, i.e. CST I, CST II, CST III and CST V, were associated with low Nugent score samples (BV negative), while CST IVC and CST IVD were associated with intermediate and high Nugent scores (BV positive) (Fig. 1). Although there were differences regarding presence/absence of specific CST in the pregnant and non-pregnant cohorts, overall microbial profiles could not be distinguished based on pregnancy status alone (Fig. 2A,B).

Figure 2.

CST and pregnancy status of participants. Jackknifed principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of Bray-Curtis distance matrices of microbial profiles from all participants in the study, with individuals coloured by CST (A) or pregnancy status (B). Samples with fewer than 1000 sequence reads (16/492) were not plotted.

Abundance of Lactobacillus spp

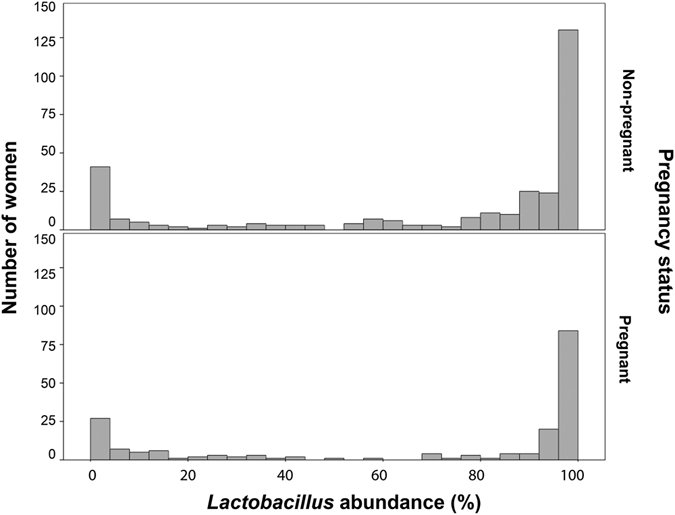

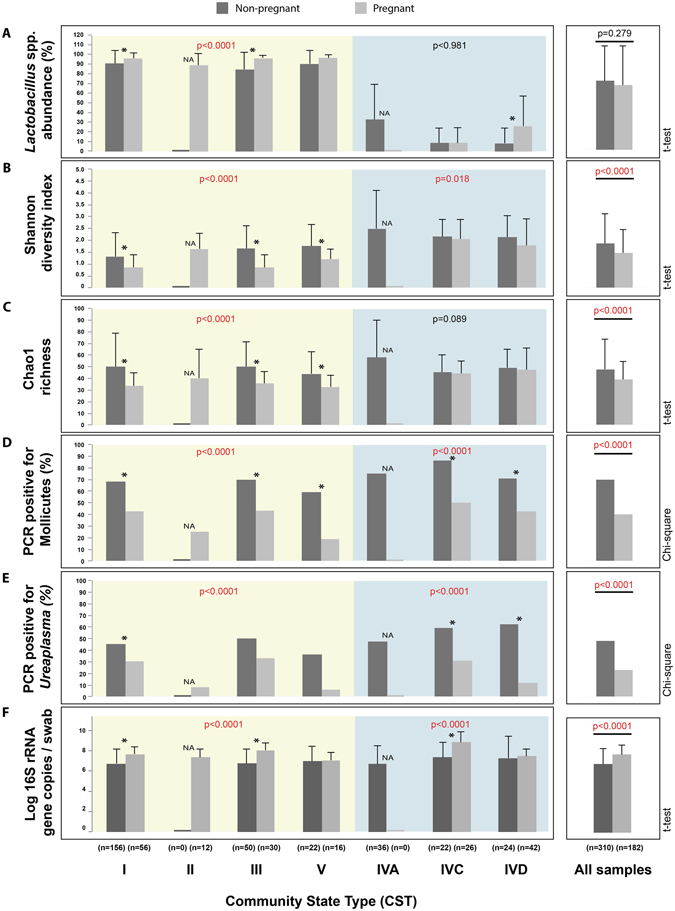

The proportion of Lactobacillus spp. in vaginal samples followed a bimodal distribution (Fig. 3). Microbiomes of most pregnant women had either low (0–20%, n = 46/182) or high (80–100%, n = 113/182) Lactobacillus spp. abundance, whereas only 23/182 (12.6%) of samples had intermediate levels (20–80%) of Lactobacillus spp. Also, pregnant women in Lactobacillus-dominated CST had greater proportions of lactobacilli (95.7% ± 6.2) (i.e. were more Lactobacillus dominated) than non-pregnant women (89.9% ± 14.8) (t-test, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4A).

Figure 3.

Lactobacillus spp. abundance. Bimodal distribution of vaginal microbiome profiles of non-pregnant (upper panel) and pregnant (lower panel) women based on Lactobacillus spp. abundance (%).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the microbial community features between pregnant and non-pregnant participants within each CST. Lactobacillus spp. abundance (A), Shannon diversity (B), Chao1 richness (C), Mollicutes prevalence (D), Ureaplasma prevalence (E) and bacterial load (F) were compared between pregnant and non-pregnant women in each CST. For continuous variables (A–C,F), the mean value is plotted with error bars indicating standard deviation. Significant differences (p < 0.05) between pregnant and non-pregnant women within each CST are indicated by an asterisk. p-values in the main panels refer to the comparison between pregnant and non-pregnant women in Lactobacillus-dominated CST (yellow panel) and non-Lactobacillus-dominated CST (blue panel). A comparison of pooled data from all CST is shown in the right-most panel. Statistical tests used are indicated on the right side of the graph.

Ecological analysis

Assessment of alpha diversity revealed that microbiomes of pregnant women were less diverse (Shannon diversity index, 1.3 ± 0.9) and less rich (Chao1, 38.9 ± 15.3) when compared to those of non-pregnant women (1.6 ± 1.1; 47.6 ± 26) (t-test, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B,C). When comparisons were conducted within CST, profiles of pregnant women in CST I, III and V were less diverse and less rich than profiles of non-pregnant women in the same category (t-test, p < 0.05) but no statistically significant differences were observed in CST IVC and IVD.

Prevalence of Mollicutes and Ureaplasma (PCR)

Mollicutes (Mycoplasma and/or Ureaplasma) were detected by family-specific conventional PCR in 74/182 (40%) of pregnant women, but prevalence varied between CST: 43%, 25%, 43%, 18%, 50% and 43% in CST I, II, III, V, IVC and IVD, respectively (Fig. 4D). Ureaplasma species were detected by genus-specific PCR in samples of 42/182 (23%) pregnant women, with 39 testing positive for U. parvum and 3 for U. urealyticum (Fig. 4E). All pregnant women PCR positive for U. urealyticum (3/3) were in CST III.

Pregnant women were less likely to be positive for Mollicutes detection by PCR when compared to non-pregnant women, regardless of CST (Chi-square, p < 0.0001, Mollicutes positive: 217/310 non-pregnant women and 74/182 pregnant women) (Fig. 4D). Additionally, pregnant women in both Lactobacillus- and non-Lactobacillus-dominated CST had lower prevalence of Ureaplasma species than non-pregnant women (Chi-square, p < 0.0001, Ureaplasma positive: 149/310 non-pregnant women and 42/182 pregnant women) (Fig. 4E).

Total bacterial load (qPCR)

Total bacterial load was assessed based on qPCR targeting the 16 S rRNA gene, and expressed as log copy number per swab (Fig. 4F). Average bacterial load was log 7.77 ± 0.93 16 S rRNA gene copies per swab (range log 4.89–10.67). Bacterial load within each CST for the pregnant women’s samples were: CST I (log 7.6 ± 0.7), CST II (log 7.3 ± 0.8), CST III (log 8.0 ± 0.7), CST V (log 7.0 ± 0.7), CST IVC (log 8.8 ± 1) and CST IVD (log 7.4 ± 0.7).

Higher bacterial loads were detected in samples from pregnant women (log 7.7 ± 0.9) when compared to non-pregnant women (log 6.8 ± 1.5) (t-test, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 4F). Comparisons within CST confirmed that samples from pregnant women in CST I (log 7.6 ± 0.7), CST III (log 8.0 ± 0.7) and CST IVC (log 8.8 ± 1) had higher bacterial load than non-pregnant women in the same categories (CST I = log 6.7 ± 1.4, CST III = log 6.7 ± 1.4. CST IVC = log 7.3 ± 1.5) (t-test, p < 0.0001). In a second analysis, samples were pooled into two groups: Lactobacillus- (I, II, III, V) and non-Lactobacillus dominated (IVA, IVC, IVD) CST. Bacterial load values were statistically different (t-test, p < 0.0001) between pregnant and non-pregnant women in both groups, with pregnant women having greater bacterial load (Lactobacillus-dominated CST: log 7.6 ± 0.8, non-Lactobacillus dominated CST: log 8 ± 1) than non-pregnant women (Lactobacillus-dominated CST: log 6.7 ± 1.4, non-Lactobacillus dominated CST: log 7.0 ± 1.8).

Relationships between microbiological and socio-demographic characteristics across the pregnant cohort

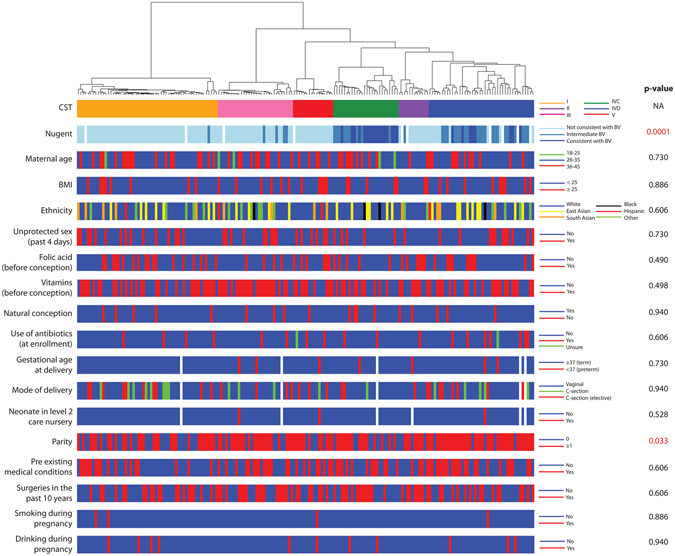

The characteristics of the microbial community of pregnant women were analyzed in terms of their relationship with the socio-demographic and clinical data. First, we determined whether there was any relationship between the CST (I, II, III, IVC, IVD, V) and demographic characteristics such as BMI, ethnicity, unprotected sex, folic acid intake, vitamins, natural conception, antibiotic use, gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery, neonatal in high level care nursery, parity, pre-existing conditions, surgeries (past 10 years), smoking and alcohol drinking status as well as Nugent score (Fig. 5). Besides Nugent score, the only significant interaction was between CST and parity (0 or ≥ 1) (Chi-square, p = 0.033), with 45% of women at parity 0 in CST I (27/60) and 23% of women at parity ≥ 1 in CST I (29/122). Microbiological and demographic characteristics were also compared to presence of Mollicutes (yes/no) and Ureaplasma (yes/no), microbiome richness (continuous variable) and diversity (continuous variable). These four observations were compared to 29 other variables (Supplementary Methods). PCR detection of Mollicutes (p = 0.017) and Ureaplasma (p = 0.017) was significantly associated with bacterial load (Chi-square).

Figure 5.

Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant participants in relation to CST. Hierarchical clustering of microbiome profiles based on Jensen-Shannon distance matrices with Ward linkage of the relative proportions each OTU within individual vaginal samples (n = 182). Demographic characteristics are indicated on the left side, and categories indicated on the right side of each row. Numbers on the right side indicate adjusted p-values of Chi-square test after false discovery rate correction. Fisher’s Exact test was conducted for variables where at least one category had an expected frequency of less than 5. Legend: white = missing data.

Although smoking has been previously shown to have a possible effect on the vaginal microbiota37, there was no significant association between CST and smoking status in this study (Chi-square, p > 0.05). Also, microbiome analysis was redone excluding samples from participants who are smokers (results not shown). The results led to the same conclusions regarding the overall microbiome (PCoA), Lactobacillus abundance, Shannon diversity, Chao1 richness, bacterial load and Mollicutes/Ureaplasma prevalence.

Discussion

In this study we characterized the vaginal microbiome of pregnant women with healthy ongoing pregnancies, at low risk of experiencing pregnancy complications such as preterm birth, and compared these results to our previously characterized cohort of non-pregnant women of similar ethnicity. We focussed our studies on the vaginal microbiome at 11–16 weeks. Pregnancy pathologies such as spontaneous preterm birth and early onset pre-eclampsia have their origins in the first or early second trimester and therapeutic interventions at this stage have been shown to be efficacious38. This is also the gestational age at which pregnant women in Canada often have their first prenatal visit with a health care provider and a vaginal swab is taken to assess the presence or absence of vaginal/cervical infections.

We used the cpn60 universal target region in our study due to its superior resolution of bacterial taxa relative to 16 S rRNA sequences39–45, its establishment as a preferred barcode for bacteria35, and the availability of a reference database of vaginal bacterial cpn60 sequences from previous studies34, 46–49. This approach has been applied to numerous animal50–52, human53 and environmental microbial populations54–57 and has previously resulted in discovery of novel community state types based on the resolution of distinct subgroups of Gardnerella vaginalis 34.

In order to make valid comparisons between pregnant and non-pregnant women microbiomes, we analysed the results from both cohorts based on socio-demographic characteristics (Table 1). The two cohorts were comparable, with no significant differences detected in any category except for maternal age and smoking. Differences regarding smoking status were not surprising since behavioural changes such as reduced drinking and smoking have been documented in pregnancy28. Although statistically significant, the identified difference in maternal age (pregnant: 33 ± 4 and non-pregnant: 30 ± 7) was not considered biologically relevant since the difference of the mean values was only 3 years.

Overall microbial profiles could not be distinguished from each other based on pregnancy status alone. However, a more detailed analysis revealed several differences between the microbiomes of healthy pregnant women and those of healthy non-pregnant women. The BV-associated CST IVA (dominated by G. vaginalis subgroup B and Atopobium) was not detected in the pregnant cohort, whereas L. gasseri dominated CST II, which was not detected among the 310 non-pregnant women in our previous study34, was detected in 12 women in the pregnant cohort. Pregnant women in Lactobacillus-dominated CST had higher relative abundance of Lactobacillus spp. when compared to non-pregnant women. Vaginal microbiomes of pregnant women had lower richness and diversity and a correspondingly lower prevalence of Mollicutes and Ureaplasma when compared to non-pregnant women.

Microbial profiles from the pregnant women clustered in six different groups, mostly Lactobacillus-dominated CST (CST I, CST II, CST III and CST V), originally defined by Ravel & Gajer58. Non-Lactobacillus-dominated (CST IV) profiles are described in the literature as either very heterogeneous or dominated with BV-associated bacteria34, 59. None of the pregnant women, including 61 with intermediate or high Nugent scores, were identified as belonging to CST IVA, which is characterized by dominance of G. vaginalis subgroup B and Atopobium 34. This distribution is notably different from the non-pregnant cohort, where 24.6% of women with intermediate or high Nugent scores were assigned to CST IVA34. Results of other studies have suggested that CST dominated by BV-associated microorganisms are less frequently detected in pregnancy30, 32. While our study design does not allow us to address the issue of overall prevalence of BV-associated CST in pregnancy, our results suggest that the distribution of these CST among pregnant women may be different than in non-pregnant women. This suggests a role CST IVA could be playing in early pregnancy loss.

OTUs that were weakly similar to Streptococcus and Weissella species were detected in most samples, but they represented only 0.33% and 0.22% of all reads, respectively. These OTUs were previously described as highly prevalent in the vaginal microbiome of healthy non-pregnant women34. They have low sequence identity to any reference sequences in the cpnDB_nr database (OTU 0026: S. devriesei 83% and OTU 0021: W. viridescens 58.8%). However, this subset of the cpnDB database contains only selected representative sequences of named species. A broader search shows that these OTU are more similar to metagenomic sequences derived from the fecal microbiome (OTU 0021 is 97% identical to Genbank accession GQ178631) or oral microbiome (OTU 0026 is 85% identical to KJ406686) that represent uncharacterized Firmicutes; reminders of the common but still uncharacterized constituents of the human microbiome.

Our findings of greater Lactobacillus abundance and lower richness and diversity in the vaginal microbiomes of pregnant women relative to non-pregnant women are consistent with previous studies in the literature. Aagaard et al.29 analyzed the microbiomes of 24 healthy, pregnant American women sampled at three different locations within the vagina. Vaginal site did not drive the structure of the microbial community, but the authors found that overall microbiomes of pregnant women were less diverse and less rich when compared to non-pregnant women. Similarly, Walther-António et al.31 described the microbiomes of 12 White pregnant American women based on longitudinal sampling and observed reduced microbiome diversity and higher Lactobacillus spp. relative abundance during pregnancy. Romero et al.30 also reported that Lactobacillus spp. abundance was significantly higher in pregnant women in comparison to non-pregnant and increased as a function of gestational age. They also described higher stability of the microbiome during pregnancy when compared to reproductive age non-pregnant women. In another longitudinal study, MacIntyre et al.32 analyzed the microbiomes of 42 British women during pregnancy and the post-partum period. L. jensenii-dominated profiles were more common among these women than Northern American women. The authors also observed that post-partum microbiomes become less Lactobacillus spp. dominant and more rich and diverse (i.e. more similar to the microbiomes of non-pregnant women) regardless of ethnicity, providing strong support for the idea that pregnancy has a transient effect on the vaginal microbial community. Importantly, the conclusions of these studies and our current study are consistent despite differences in the cohort studied (Canadian, American or European cohorts of varying mixtures of ethnicity), universal target amplified (cpn60 universal target or 16 S rRNA gene) or sequencing platforms used (454/Roche pyrosequencing or Illumina MiSeq).

The explanations for these pregnancy-associated changes are not well established, but a relationship between sex steroid hormone levels and the composition of the vaginal microbiome has been previously reported58, 60, 61. Increased levels of estrogen during pregnancy lead to increased thickness of the vaginal mucosa and increased deposition of glycogen62, 63. Glycogen is the main carbohydrate utilized by Lactobacillus spp. for the production of lactic acid, which contributes to the protective effect of a low vaginal pH64–67. This may contribute to the greater dominance of Lactobacillus in pregnancy and, consequently, the lower richness and diversity in this cohort.

A novel finding in our study was the lower prevalence of Mollicutes and Ureaplasma in pregnancy detected by family and genus-specific PCR. Mollicutes have been associated with preterm birth, preterm premature rupture of membranes and low birth weight68–70. The lower prevalence of Mollicutes and Ureaplasma is consistent with the overall lower species richness and diversity in the vaginal microbiomes of pregnant relative to non-pregnant women. We also found that pregnant women had higher bacterial load than non-pregnant women as estimated by quantitative PCR targeting the 16 S rRNA gene. Hormone induced production of glycogen may offer a nutritionally richer environment for bacterial growth in the vagina during pregnancy. Additionally, it is known that pregnancy alters the amount and consistency of the mucus, which becomes more abundant and thicker71. Thus, it is possible that swabs sampled from the pregnant women carried more material when compared to non-pregnant women. We are unable to resolve this question since the swabs were not weighed before DNA extraction steps. In addition to pregnancy associated physiological differences and mucus consistency, other technical factors such as storage conditions or inherent differences in the study populations cannot be ruled out.

One limitation of this study was the assessment of pregnancy outcomes and microbial profiles since there were very few poor outcomes in this cohort, as it would be expected for a low risk group. This study, however, does provide crucial baseline information for future studies in pregnant women. In addition, we detected significant interaction between parity and CST. Considering the large number of variables in the metadata, analysis of these associations should be interpreted with caution. We can speculate that the prevalence of the L. crispatus-dominated CST I among nulliparous women might be associated with more cautious or health conscious behaviour among women in their first gestation. Pregnancy-induced physiologic alterations that can persist after delivery have been previously reported72. In addition to physiologic changes, a disturbed vaginal microbiome that persisted for up to a year post-partum has also recently been described33. Those persistent changes might explain the association between CST and parity we observed, with post-partum microbiome changes affecting the current status of primiparous and multiparous women. Further studies are needed to investigate these relationships in more detail.

In conclusion, we have identified several differences in the composition of the vaginal microbial communities of pregnant women living in Canada relative to non-pregnant women: larger total bacterial community, lower richness and diversity, higher Lactobacillus abundance and lower Mollicutes/Ureaplasma prevalence. These findings give us a better understanding of the vaginal microbiome in pregnancy, which is a critical step toward being able to exploit the diagnostic potential of the microbiome for the prediction of adverse pregnancy outcomes as well as to explore alternative therapeutic procedures through microbiological intervention. Establishing an understanding of the normal microbiome in low risk pregnant women is a vital baseline for comparison to the microbiome of women who have adverse perinatal outcomes such as preterm birth.

Methods

Study population and sampling

This study received ethical approval from the Mount Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board (Approval Number 08-0005-A). All participants provided written informed consent and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Women attending antenatal clinics at Mount Sinai Hospital (Toronto, ON, Canada) between May 2012 and October 2013 were invited to be part of a clinical trial to determine the effect of oral probiotic lactobacilli in altering the vaginal microbiome in asymptomatic pregnant women with an abnormal Nugent score73, 74. Nugent score was determined on Gram-stained swabs taken at the same time as the swab for microbial analysis. Women with normal Nugent scores were excluded from the probiotic trial and are included in this analysis. Samples from women with an abnormal Nugent score who were subsequently randomized and included in the analysis for this study were taken prior to any intervention in these women and there was no difference in the pregnancy outcomes between the lactobacilli and placebo groups74. A preliminary report on the results of that probiotic trial have been presented previously74.

Women were eligible to participate if the following inclusion criteria were met: currently pregnant, adequate comprehension of English language to sign written informed consent, age ≥ 18 years old, no evidence of fetal complications such as intrauterine growth restriction, and no evidence of medical complications of pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included inability to provide informed written consent, multi-fetal pregnancies, currently taking antibiotics or other antimicrobial therapy for BV treatment. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools75.

Vaginal swabs were collected under direct visualization using a speculum by either a physician or a nurse and placed in dry tubes prior to being placed in −80 °C. A total of 182 pregnant women at 11–16 weeks gestation were enrolled in the vaginal microbiome study, including 111 women with normal Nugent scores (inconsistent with BV), 61 women with Nugent scores that were intermediate or consistent with BV, and 10 women with indeterminate Nugent scores due to poor quality smears. Total nucleic acid was extracted from swabs using the MagMAX™ Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, Burlington, ON, Canada) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Kit reagents are aliquoted to eliminate repeated accessing of open reagents, and samples are processed in small batches using filter-tips to prevent cross-contamination. Pipettes and other lab surfaces are regularly treated with DNA surface decontaminant (DNA Away, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Regular monitoring of reagent only DNA extraction controls in our lab by universal PCR confirms that these procedures are sufficient to eliminate detectable template contamination of study samples.

The microbial profiles of low-risk pregnant women were compared to profiles previously generated from healthy, reproductive aged, non-pregnant Canadian women from the greater Vancouver area, British Columbia, Canada (n = 310)34. Samples were collected as being non-menstrual but were not sampled at any specific non-menstrual cycle time as other studies have demonstrated there is little variation in microbiome profiles through the cycle48. Samples from this previous study were processed in the same way as in the current work in terms of swab type, storage temperature, DNA extraction, library preparation and sequencing. Although the year of sampling was different between the two cohorts, there was no difference in time from sample collection to sequencing between the two groups.

Total Bacterial DNA (qPCR) and Detection of Mollicutes (PCR)

Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Total bacterial DNA quantity in each sample was estimated using a SYBR Green assay based on amplification of the V3 region of the 16 S rRNA gene. Primer sequences were as follows: SRV3-1 (5′-CGGYCCAGACTCCTAC-3′), SRV3-2 (5′-TTACCGCGGCTGCTGGCAC-3′)76. Reactions run on a MyiQ thermocycler using the following cycling parameters: 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 15 sec., 62 °C for 15 sec., 72 °C for 15 sec., with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 minutes77.

Conventional PCR: Some Mollicutes (Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma) species lack a cpn60 gene78. Thus, we performed a family-specific semi-nested PCR targeting the 16 S rRNA gene to detect Mollicutes79, and a PCR targeting the multiple banded antigen gene to detect Ureaplasma spp.. In this assay, PCR products from Ureaplasma parvum and U. urealyticum can be differentiated by size80.

cpn60 Universal Target (UT) PCR and Pyrosequencing

Universal primer PCR targeting the 552–558 bp cpn60 UT region was performed using a mixture of cpn60 primers consisting of a 1:3 molar ratio of primers H279/H280:H1612/H1613, as described previously47, 48, 81. To avoid cross-contamination, samples were handled in small batches, and a no template control was included with each set of PCR reactions. To allow multiplexing of samples in a single sequencing run, primers were modified at the 5′ end with one of 24 unique decamer multiplexing identification (MID) sequences, as per the manufacturer’s recommendations (Roche, Brandford, CT, USA). Amplicons were pooled in equimolar amounts for sequencing on the Roche GS Junior sequencing platform. The sequencing libraries were prepared using the GS DNA library preparation kit and emulsion PCR (emPCR) was performed with a GS emPCR kit (Roche Diagnostics, Laval, Canada).

Analysis of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU)

Raw sequence data was processed by using the default on-rig procedures from 454/Roche. Filter-passing reads were used in the subsequent analyses for each of the pyrosequencing libraries. MID-partitioned sequences were mapped using Bowtie 2 (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/) on to a manually curated reference set of 1,561 OTU sequences representing human vaginal microbiota. Bowtie 2 was run using the default end-to-end alignment mode, in which the minimum “cutoff” for any individual read to be validly aligned to a reference sequence is an alignment score of −0.6 + −0.6 * L, where L is the length of the read. The best valid alignment for each read is reported. Mapping quality was also evaluated by MAPQ value, which is based on the probability that alignment does not correspond to the read’s true point of origin.

The OTU reference set was generated originally by de novo assembly of cpn60 sequence reads from each of 546 vaginal microbiomes, which included 182 samples from pregnant women (this study) and 364 samples from non-pregnant women from previous studies by our research group. The reference assembly was created by the microbial Profiling Using Metagenomic Assembly pipeline (mPUMA, http://mpuma.sourceforge.net)82 with Trinity as the assembly tool83. Assembled OTU were labeled according to their nearest reference sequence determined by watered-Blast comparison84 to the cpn60 reference database, cpnDB_nr (downloaded from http://www.cpndb.ca 78). cpnDB_nr is a subset of the cpnDB database that includes a non-redundant collection of sequences representing all species in cpnDB, with a preference for inclusion of the type strain for each species when available. This reference assembly approach allows us to compare the microbial profiles from various cohorts under investigation, including the 182 pregnant women described in this study. To improve comprehension of some figures, we have pooled reads from OTU into “nearest neighbour species” based on their taxonomic label. Thus, the term “species” refers to OTUs that have the same nearest neighbour match in cpnDB.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons across pregnancy status cohorts were based on analysis of variance (ANOVA), t-test and Chi-square, performed in IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 21) at 5% level of significance. For analysis of associations between socio-demographic characteristics and microbiome profiles, a false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons was applied85 (for the complete list of variables tested, see Supplementary Methods).

Alpha (Shannon diversity and Chao1 estimated species richness) and beta diversity (jackknifed Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices) were calculated as the mean of 100 subsamplings of 1000 reads (or all reads available when less than 1000) in QIIME (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology)86. Plots of alpha diversity measures against bootstrap sample number were generated in R and visually inspected to ensure that an adequate sampling depth for each sample was achieved. Microbiome profiles were also compared based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity matrices using Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) in QIIME.

For community state type analysis, a Jensen-Shannon distance matrix was calculated using the ‘vegdist’ function in the vegan package87 with a custom distance function that calculates the square root of the Jensen-Shannon divergence88. This distance matrix was used for hierarchical clustering using the ‘hclust’ function in R, with Ward linkage.

Data Availability

Raw sequence data files for the 182 samples described in this study were deposited to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (Accession SRP073152, BioProject PRJNA317763). Due to ethical and legal restrictions related to protecting participant privacy imposed by the Mt. Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board, all other relevant data are available upon request pending ethical approval. Please submit all requests to initiate the data access process to the corresponding author.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the women who participated in the study and to the research staff at Mount Sinai Hospital. Financial support was provided by a joint Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Emerging Team Grant and a Genome British Columbia (GBC) grant awarded to DMM, AB and JEH (grant reference #108030) as well as a CIHR grant MOP-82799 to AB. ACF was supported by a University of Saskatchewan graduate scholarship.

Author Contributions

D.M., A.B., J.E.H. and the other members of the VOGUE Research Group conceived the study. D.M., A.B., and J.E.H. oversaw and contributed to data collection and analysis, and participated in manuscript review. A.C.F. generated the Mollicutes PCR, data analysis and manuscript writing. A.C.F. and B.C. generated cpn60 vaginal microbiome profiles and 16 S rRNA qPCR. M.R. recruited study participants and assisted in the collection of samples and data collection. S.Y. assisted in the collection and processing of samples as well as study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

A comprehensive list of consortium members appears at the end of the paper.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07790-9

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Deborah M. Money, Email: deborah.money@ubc.ca

The VOGUE Research Group:

Sean Hemmingsen, Gregor Reid, Tim Dumonceaux, Gregory Gloor, Matthew Links, Kieran O’Doherty, Patrick Tang, Julianne van Schalkwyk, and Mark Yudin

References

- 1.Ryckman KK, Simhan HN, Krohn MA, Williams SM. Predicting risk of bacterial vaginosis: the role of race, smoking and corticotropin-releasing hormone-related genes. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2009;15:131–7. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobel, J. D. Bacterial vaginosis. Annu. Rev. Med. 349–356 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Brotman RM. Vaginal microbiome and sexually transmitted infections: an epidemiologic perspective. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:4610–4617. doi: 10.1172/JCI57172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oakley BB, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM, Fredricks DN. Diversity of human vaginal bacterial communities and associations with clinically defined bacterial vaginosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:4898–4909. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02884-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou X, et al. Recent advances in understanding the microbiology of the female reproductive tract and the causes of premature birth. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010;2010:737425. doi: 10.1155/2010/737425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsson P-G, Platz-Christensen J-J, Thejls H, Forsum U, Påhlson C. Incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease after first-trimester legal abortion in women with bacterial vaginosis after treatment with metronidazole: A double-blind, randomized study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992;166:100–103. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larsson PG, et al. Treatment with 2% clindamycin vaginal cream prior to first trimester surgical abortion to reduce signs of postoperative infection: a prospective, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2000;79:390–396. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2000.079005390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donders GG, et al. Relationship of bacterial vaginosis and mycoplasmas to the risk of spontaneous abortion. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000;183:431–437. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ralph ASG, Rutherford AJ, Wilson JD. Influence of bacterial vaginosis on conception and miscarriage in the first trimester: cohort study. Br. Med. J. 2015;319:220–223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7204.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llahi-Camp JM, Rai R, Ison C, Regan L, Taylor-robinson D. Association of bacterial vaginosis with a history of second trimester miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 1996;11:1575–1578. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hay PE, Lamont RF, Taylor-robinson D, Morgan DJ, Ison C. Abnormal bacterial colonisation of the genital tract and subsequent preterm delivery and late miscarriage. Br. Med. J. 1994;308:295–298. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6924.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibbs RS. Chorioamnionitis and bacterial vaginosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1993;169:460–462. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90341-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillier SL, et al. A Case–Control Study of Chorioamnionic Infection and Histologic Chorioamnionitis in Prematurity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;319:972–978. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for post-cesarean endometritis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990;75:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobsson B, Pernevi P, Chidekel L, Platz-Christensen J-J. Bacterial vaginosis in early pregnancy may predispose for preterm birth and postpartum endometritis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2002;81:1006–1010. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.811103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parry S, Strauss JF. Premature rupture of the fetal membranes. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;338:663–670. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillier SL, et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birth-weight infant. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1737–1742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leitich H, et al. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;189:139–147. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behrman, R. E. & Butler, A. S. Preterm Birth: causes, consequences, and prevention. (National Academies Press, doi:10.17226/11622 2007). [PubMed]

- 20.Mwaniki MK, Atieno M, Lawn JE, Newton CRJC. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes after intrauterine and neonatal insults: A systematic review. Lancet. 2012;379:445–452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61577-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu L, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379:2151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tulchinsky D, Hobel CJ, Yeager E, Marshall JR. Plasma estrone, estradiol, estriol, progesterone, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone in human pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1972;112:1095–1100. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(72)90185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jamieson DJ, Theiler RN, Rasmussen SA. Emerging infections and pregnancy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:1638–1643. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mor G, Cardenas I. The immune system in pregnancy: a unique complexity. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010;63:425–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.House M, Kaplan DL, Socrate S. Relationships between mechanical properties and extracellular matrix constituents of the cervical stroma during pregnancy. Semin. Perinatol. 2009;33:300–307. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo L, et al. Interleukin-8 levels and granulocyte counts in cervical mucus during pregnancy. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2000;43:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.8755-8920.2000.430203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee DC, et al. Protein profiling underscores immunological functions of uterine cervical mucus plug in human pregnancy. J. Proteomics. 2011;74:817–828. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crozier SR, et al. Do women change their health behaviours in pregnancy? Findings from the Southampton women’s survey. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2009;23:446–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aagaard KM, et al. A metagenomic approach to characterization of the vaginal microbiome signature in pregnancy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romero R, et al. The composition and stability of the vaginal microbiota of normal pregnant women is different from that of non-pregnant women. Microbiome. 2014;2:4. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walther-António MRS, et al. Pregnancy’s stronghold on the vaginal microbiome. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacIntyre DA, et al. The vaginal microbiome during pregnancy and the postpartum period in a European population. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8988. doi: 10.1038/srep08988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiGiulio DB, et al. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:11060–11065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502875112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Albert AYK, et al. A study of the vaginal microbiome in healthy Canadian women utilizing cpn60-based molecular profiling reveals distinct Gardnerella subgroup community state types. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Links MG, Dumonceaux TJ, Hemmingsen SM, Hill JE. The haperonin-60 universal target is a barcode for bacteria that enables de novo assembly of metagenomic sequence data. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ravel J, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011;108:4680–4687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brotman RM, et al. Association between cigarette smoking and the vaginal microbiota: a pilot study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014;14:471. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberge S, et al. Early administration of low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preterm and term preeclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2012;31:141–146. doi: 10.1159/000336662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paramel Jayaprakash T, Schellenberg JJ, Hill JE. Resolution and characterization of distinct cpn60-based subgroups of Gardnerella vaginalis in the vaginal microbiota. PLoS One. 2012;7:e43009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vermette CJ, Russell AH, Desai AR, Hill JE. Resolution of phenotypically distinct strains of Enterococcus spp. in a complex microbial community using cpn60 universal target sequencing. Microb. Ecol. 2010;59:14–24. doi: 10.1007/s00248-009-9601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verbeke TJ, et al. Predicting relatedness of bacterial genomes using the chaperonin-60 universal target (cpn60 UT): Application to Thermoanaerobacter species. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2011;34:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill JE, et al. Identification of Campylobacter spp. and discrimination from Helicobacter and Arcobacter spp. by direct sequencing of PCR-amplified cpn60 sequences and comparison to cpnDB, a chaperonin reference sequence database. J. Med. Microbiol. 2006;55:393–399. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lan Y, Rosen G, Hershberg R. Marker genes that are less conserved in their sequences are useful for predicting genome-wide similarity levels between closely related prokaryotic strains. Microbiome. 2016;4:18. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masson L, et al. Identification of pathogenic Helicobacter species by chaperonin-60 differentiation on plastic DNA arrays. Genomics. 2006;87:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brousseau R, et al. Streptococcus suis serotypes characterized by analysis of chaperonin 60 gene sequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:4828–4833. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4828-4833.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hill JE, et al. Characterization of vaginal microflora of healthy, nonpregnant women by chaperonin-60 sequence-based methods. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;193:682–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schellenberg JJ, et al. Molecular definition of vaginal microbiota in East African commercial sex workers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:4066–74. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02943-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chaban B, et al. Characterization of the vaginal microbiota of healthy Canadian women through the menstrual cycle. Microbiome. 2014;2:23. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schellenberg JJ, et al. Selection, phenotyping and identification of acid and hydrogen peroxide producing bacteria from vaginal samples of Canadian and East African women. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mckenney EA, Ashwell M, Lambert JE, Fellner V. Fecal microbial diversity and putative function in captive western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), Hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas) and binturongs (Arctictis binturong) Integr. Zool. 2014;9:557–569. doi: 10.1111/1749-4877.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costa MO, Chaban B, Harding JCS, Hill JE. Characterization of the fecal microbiota of pigs before and after inoculation with ‘Brachyspira hampsonii’. PLoS One. 2014;9:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Desai AR, et al. Effects of plant-based diets on the distal gut microbiome of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Aquaculture. 2012;350–353:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2012.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peterson SW, et al. A study of the infant nasal microbiome development over the first year of life and in relation to their primary adult caregivers using cpn60 universal target (UT) as a phylogenetic marker. PLoS One. 2016;11:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bondici VF, et al. Microbial communities in low permeability, high pH uranium mine tailings: Characterization and potential effects. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013;114:1671–1686. doi: 10.1111/jam.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dumonceaux TJ, et al. Molecular characterization of microbial communities in Canadian pulp and paper activated sludge and quantification of a novel Thiothrix eikelboomii-like bulking filament. Can. J. Microbiol. 2006;52:494–500. doi: 10.1139/w05-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Links MG, et al. Simultaneous profiling of seed-associated bacteria and fungi reveals antagonistic interactions between microorganisms within a shared epiphytic microbiome on Triticum and Brassica seeds. New Phytol. 2014;202:542–553. doi: 10.1111/nph.12693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oliver KL, Hamelin RC, Hintz WE. Effects of transgenic hybrid aspen overexpressing polyphenol oxidase on rhizosphere diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;74:5340–5348. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02836-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brotman RM, Ravel J, Bavoil PM, Gravitt PE, Ghanem KG. Microbiome, sex hormones, and immune responses in the reproductive tract: challenges for vaccine development against sexually transmitted infections. Vaccine. 2014;32:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Romero R, et al. The vaginal microbiota of pregnant women who subsequently have spontaneous preterm labor and delivery and those with a normal delivery at term. Microbiome. 2014;2:18. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Devillard E, Burton JP, Hammond J-A, Lam D, Reid G. Novel insight into the vaginal microflora in postmenopausal women under hormone replacement therapy as analyzed by PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2004;117:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farage MA, Miller KW, Sobel JD. Dynamics of the vaginal ecosystem - Hormonal influences. Infect. Dis. Res. Treat. 2010;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 62.BMJ. Oestrogens and vaginal glycogen. Br. Med. J. 2, 753 (1943).

- 63.Cruickshank R, Sharman A. The biology of the vagina in the human subject. II The bacterial flora and secretion of the vagina at various age-periods and their relations to glycogen in the vaginal epitehlial. BJOG An Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1934;41:190–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1934.tb08758.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mirmonsef P, et al. Free glycogen in vaginal fluids is associated with Lactobacillus colonization and low vaginal pH. PLoS One. 2014;9:26–29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prince AL, Antony KM, Chu DM, Aagaard KM. The microbiome, parturition, and timing of birth: more questions than answers. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2014;104–105:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.O’Hanlon DE, Moench TR, Cone RA. Vaginal pH and microbicidal lactic acid when lactobacilli dominate the microbiota. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cruickshank R. The conversion of the glycogen of the vagina into lactic acid. J. Pathol. Bacteriol. 1934;39:213–219. doi: 10.1002/path.1700390118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perni SC, et al. Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in midtrimester amniotic fluid: Association with amniotic fluid cytokine levels and pregnancy outcome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;191:1382–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foxman B, et al. Mycoplasma, bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria BVAB3, race, and risk of preterm birth in a high-risk cohort. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014;210:226.e1–226.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kwak D-W, Hwang H-S, Kwon J-Y, Park Y-W, Kim Y-H. Co-infection with vaginal Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis increases adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with preterm labor or preterm premature rupture of membranes. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2014;27:333–337. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.818124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chrétien FC. Ultrastructure and variations of human cervical mucus during pregnancy and the menopause. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1978;57:337–348. doi: 10.3109/00016347809154028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clifton VL, Stark MJ, Osei-Kumah A, Hodyl NA. Review: The feto-placental unit, pregnancy pathology and impact on long term maternal health. Placenta. 2012;33:S37–S41. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang SW, et al. Oral Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1/L. reuteri RV-14 does not change the vaginal microbiome or cervico-vaginal cytokines in low risk pregnant women with an abnormal Nugent score. Reprod. Sci. 2015;22:55A–390A. doi: 10.1177/1933719115579631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Harris PA, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee D, Zo Y, Kim S. Nonradioactive method to study genetic profiles of natural bacterial communities by PCR – single-strand-conformation polymorphism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:3112–3120. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3112-3120.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chaban B, et al. Characterization of the upper respiratory tract microbiomes of patients with pandemic H1N1 influenza. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hill JE, Penny SL, Crowell KG, Goh SH, Hemmingsen SM. cpnDB: a chaperonin sequence database. Genome Res. 2004;14:1669–75. doi: 10.1101/gr.2649204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van Kuppeveld FJM, et al. Genus- and species-specific identification of mycoplasmas by 16S rRNA amplification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992;58:2606–2615. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2606-2615.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Watson HL, Blalock DK, Cassell GH. Variable antigens of Ureaplasma urealyticum containing both serovar-specific and serovar-cross-reactive epitopes. Infect. Immun. 1990;58:3679–3688. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3679-3688.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hill JE, Town JR, Hemmingsen SM. Improved template representation in cpn60 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product libraries generated from complex templates by application of a specific mixture of PCR primers. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;8:741–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Links MG, Chaban B, Hemmingsen SM, Muirhead K, Hill JE. mPUMA: a computational approach to microbiota analysis by de novo assembly of operational taxonomic units based on protein-coding barcode sequences. Microbiome. 2013;1:23. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grabherr MG, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schellenberg JJ, et al. Pyrosequencing of the chaperonin-60 universal target as a tool for determining microbial community composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:2889–98. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01640-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oksanen, A. J. et al. Community Ecology Package ‘vegan’. R version 2.3-1. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/(2015).

- 88.Endres DM, Schindelin JE. A new metric for probability distributions. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 2003;49:1858–1860. doi: 10.1109/TIT.2003.813506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequence data files for the 182 samples described in this study were deposited to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (Accession SRP073152, BioProject PRJNA317763). Due to ethical and legal restrictions related to protecting participant privacy imposed by the Mt. Sinai Hospital Research Ethics Board, all other relevant data are available upon request pending ethical approval. Please submit all requests to initiate the data access process to the corresponding author.