Abstract

The WRKY family, one of the largest families of transcription factors, plays important roles in the regulation of various biological processes, including growth, development and stress responses in plants. In the present study, 63 DoWRKY genes were identified from the Dendrobium officinale genome. These were classified into groups I, II, III and a non-group, each with 14, 28, 10 and 11 members, respectively. ABA-responsive, sulfur-responsive and low temperature-responsive elements were identified in the 1-k upstream regulatory region of DoWRKY genes. Subsequently, the expression of the 63 DoWRKY genes under cold stress was assessed, and the expression profiles of a large number of these genes were regulated by low temperature in roots and stems. To further understand the regulatory mechanism of DoWRKY genes in biological processes, potential WRKY target genes were investigated. Among them, most stress-related genes contained multiple W-box elements in their promoters. In addition, the genes involved in polysaccharide synthesis and hydrolysis contained W-box elements in their 1-k upstream regulatory regions, suggesting that DoWRKY genes may play a role in polysaccharide metabolism. These results provide a basis for investigating the function of WRKY genes and help to understand the downstream regulation network in plants within the Orchidaceae.

Introduction

Transcription factors (TFs) are proteins that bind to specific DNA sequences and regulate the downstream expression of genes at the level of transcription, thereby influencing and controlling various biological processes1. Among the TF families, the WRKY family is a superfamily of TFs with 88 and 129 members in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and rice (Oryza sativa), respectively (http://plntfdb.bio.uni-potsdam.de/v3.0/). WRKY proteins contain one or two highly conserved amino acid sequences, namely WRKY domain (WRKYGQK), with one or two zinc-finger-like motifs2, 3. The WRKY domain and zinc-finger-like motif have a DNA-binding domain that is responsible for the recognition of the W-box sequence, (C/T)TGAC(T/C)2, 4. Based on the number of WRKY domains and the type of zinc-finger motifs, WRKY proteins have been classified into three main groups: group I, II and III2, 3, 5. In addition, group II was subdivided into five subgroups, IIa, IIb, IIc, IId and IIe, based on phylogenetic analyses3. WRKY proteins in group I contain two WRKY domains and two zinc-finger motifs2, 6. Both group II and III WRKY proteins contain a single WRKY domain and a zinc-finger motif, while group III proteins have a zinc-finger motif with a C-C-H-C zinc-finger structure rather than C-C-H-H2, 3, 5.

The first WRKY gene (SPF1) from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) was identified and characterized in 19947. Since then, numerous WRKY genes have been cloned and characterized from various plant species such as wheat (Triticum aestivum)8, soybean (Glycine max)9, rice10 and even an orchid, Dendrobium officinale 11. WRKY family members have also been identified and analyzed at the genome level. To date, genome-wide WRKY analyses have been performed in various plant species including arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana)2, rice6, cucumber (Cucumis sativus)12, Brachypodium distachyon 13, birdsfoot trefoil (Lotus japonicas)14, grape15, carrot (Daucus carota)16, cassava (Manihot esculenta)17, and other plants.

Generally, WRKY proteins are regarded as positive or negative regulators and play a broad-spectrum regulatory role in developmental and physiological processes. In plants, WRKY proteins have been demonstrated to act in the growth of leaves and stems18, senescence19 and dormancy20. Accumulating data has also demonstrated that WRKY proteins play regulatory roles in biotic stress caused by viruses21, bacterial pathogens22, fungi23 and oomycetes24, as well as in various abiotic stresses, including wounding, cold, heat, drought or salinity25. The regulation of WRKY genes in abiotic stress has been increasingly characterized in recent years. For example, a WRKY TF AtWRKY46 regulated osmotic stress responses and stomatal movement in A. thaliana 26. GmWRKY27 interacted with GmMYB174 to reduce the expression of a negative stress tolerance factor GmNAC29 to improve salt and drought tolerance27. Wheat TaWRKY2 and TaWRKY44 genes are involved in multiple abiotic stress tolerance, including to drought, salt, freezing and osmotic stress28, 29.

D. officinale is an important traditional Chinese medicine30. Studies on TFs in D. officinale, or even in other orchids, are rarely reported, although genomic data for D. officinale and other orchids has emerged in the past two years31–33. In this study, a total of 63 WRKY genes from D. officinale were identified, analyzed or classified, and their conserved motif composition and expression were assessed under cold stress. Furthermore, potential WRKY target genes were investigated and annotated. Comprehensive studies of the WRKY family genes and WRKY target genes in D. officinale will shed light on the functions of this TF family in orchids.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and stress treatments

D. officinale seedlings, which were used for the cold stress treatment, were cultured on half-strength Murashige and Skoog34 (MS) medium containing 2% sucrose and 0.6% agar (pH 5.4), in a growth chamber (26 ± 1 °C, 40 µmol m−2 s−1, a 12-h photoperiod and 60% relative humidity). To detect the expression of WRKY family genes under cold stress, plantlets about 10 months after germination and 8–9 cm in height were subjected to cold stress treatment. Plantlets grown on agar-based medium were carefully removed and transferred to half-strength MS liquid medium containing 2% sucrose (pH 5.4), and used as the control. For cold stress, plantlets on the same medium as the control were transferred to a 4 °C growth chamber. The roots and stems were harvested from four time points (0 h, 2 h, 6 h and 12 h), frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C within three days. Six plantlets were pooled as one biological replicate and for each experiment there were three biological replicates.

Identification of WRKY genes in D. officinale and phylogenetic analysis

The Coding DNA Sequence (CDS) file of D. officinale was downloaded from the Herbal Medicine Omics Database (http://202.203.187.112/herbalplant/)32. The hidden Markov model (HMM) profile of WRKY with accession number PF03106 was downloaded from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/). All putative DoWRKY TFs were obtained by screening D. officinale protein sequences using HMMER 3.0 software (http://hmmer.janelia.org/). The putative DoWRKY sequences were checked by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). All putative DoWRKY proteins that were confirmed to be WRKY proteins in the NCBI database were considered as DoWRKY proteins. DoWRKY proteins without a WRKYGQK motif and redundant genes were discarded. The proteins containing the WRKYGQK domain without a zinc-finger structure were perceived as incomplete genes and 3′ ends were generated by a SMARTer RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Clontech Laboratories; see supplementary method 1). All the remaining validated protein DoWRKY sequences and selected AtWRKY proteins (detailed information in Supplementary text 1) were aligned using ClustalX version 2.135 and a phylogenetic tree was constructed with a bootstrapped Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method.

Conserved motif distributions and gene structure analysis

Conserved motifs for each DoWRKY amino acid sequence were analyzed by Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) Suite (version 4.11.2; http://meme.nbcr.net/meme/). The parameters for motif identification were set as follows: maximum number, 20; site distribution, any number of repetitions; minimum width, 10; and maximum width, 50. For gene structure analysis, the corresponding genome sequences of DoWRKY genes were obtained from the genome sequences of D. officinale which were downloaded from the Herbal Medicine Omics Database (http://202.203.187.112/herbalplant/)32 and from the whole genome sequence of D. officinale (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession code: JSDN00000000)33. Genomic and CDS sequences were used for drawing gene structure schematic diagrams with the Gene Structure Display Server from the Center for Bioinformatics at Peking University (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/index.php)36.

Analysis of the cis-regulatory elements in the promoters of DoWRKY genes

The upstream 1-k (kilobase) regulatory regions (from the translation start site) of DoWRKY genes were obtained from the Herbal Medicine Omics Database or the whole genome sequence of D. officinale described above. The cis-elements were downloaded from the database of Plant Cis-acting Regulatory DNA Elements (PLACE, https://dbarchive.biosciencedbc.jp/en/place/download.html)37 and used as queries to scan cis-elements to test their presence on both strands of 1-k upstream regulatory regions. The positions of both abiotic and biotic stress-responsive elements were marked and shown in a diagram by drawing a gene physical map based on Perl and Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) script.

Identification and annotation of potential WRKY target genes

The 1-k promoter DNA sequence upstream of the ATG start codon of each assembled gene from the Herbal Medicine Omics Database was extracted from the genome sequence of D. officinale downloaded from the Herbal Medicine Omics Database and used to scan for the presence of the WRKY TF binding site element with the sequence (C/T)TGAC(C/T), which represents the consensus DNA sequence of all WRKY TF binding sites that were experimentally verified in plants38. To improve the recognition rate between TFs and dehydration-responsive elements, three or more dehydration-responsive elements were proposed to exist in the upstream region, as identified by a yeast one-hybrid method39. Thus, the WRKY target genes possess at least three potential WRKY binding sites that were used for further functional annotations using NCBI, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) databases. For a sequence similarity search, gene annotation was performed by BLASTX at NCBI Non-redundant (Nr, ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/db/FASTA/nr.gz) with a typical cutoff E value of < 10–5. The GO (http://www.geneontology.org/) database was used to perform functional classification to help understand the distribution of gene functions at a macro level by using WEGO software40. KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), a major public pathway-related database, was consulted to analyze metabolic processes of WRKY target genes.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis

Total RNAs were extracted from samples using Column Plant RNAout2.0 (Tiandz, Inc., Beijing, China) and then reverse transcribed into cDNA by the GoScript™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Three independent PCR reactions were carried out for the 63 putative genes using the SoAdvanced™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol in an ABI 7500 Real-time system (ABI, CA, USA). Amplification conditions were 95 °C for 30 s and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 30 s, with a melting curve over a temperature range of 65–95 °C in 0.5 °C increments to check the amplification specificity. D. officinale actin (NCBI accession number: JX294908), was used as an internal control to normalize the expression of DoWRKY genes based on the advice of He et al.41. Relative gene expression was calculated with the 2−ΔΔCT method42. Gene-specific DNA primers for qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Cluster analysis of expression data

The expression profiles via a heat-map of roots and stems were calculated from the log1.5 (2−ΔΔCT) value, and shown by a green-red gradient in R version 3.4.0. The data were statistically analyzed using SigmaPlot12.3 software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test. The up-regulated genes were defined as a fold change greater than 1.5 with a P-value of 0.05, and a fold change of ≤ 0.66 was used to define down-regulated genes when the P-value was < 0.05. For expression profiles in leaves under cold stress, the raw sequencing reads of leaves under normal conditions (SRR3210630, SRR3210635 and SRR3210636) and treated at 4 °C for 20 h (SRR3210613, SRR3210621 and SRR3210626) were downloaded from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) provided by Wu et al.43. All usable reads were mapped with DoWRKY gene nucleotide sequences using TopHat version 2.0.844, and gene expression level was then calculated by the FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped) method using cufflinks version 2.1.145. The genes with FPKM > 10 in control or cold-treated leaves were regarded as valid genes for which fold change (mean of FPKMtreat/mean of FPKMcontrol) was calculated. Genes with a ≥ 1.5-fold change and deviation probability ≥ 0.8 were defined as up-regulated genes, and those with a ≤ 0.66-fold change and deviation probability ≥ 0.8 were regarded as down-regulated genes.

Results

Identification of DoWRKY transcription factors in D. officinale

A total of 83 putative WRKY genes were obtained by the HMMER3.0 platform and 81 of these genes were further analyzed to confirm the presence of the WRKY domain by NCBI BLAST. The 81 WRKY genes were termed DoWRKY1 to DoWRKY81. The DoWRKY proteins without a WRKY domain and redundant genes were excluded. After this exclusion, 63 Nr WRKY genes were obtained and 3′ end RACE was performed (Supplementary method 1). The 63 DoWRKY amino acid sequences are listed in Supplementary text 2. All 63 WRKY proteins contained a WRKY domain and their lengths ranged from 110 (DoWRKY60) to 731 (DoWRKY37) amino acids, with an average of 329 amino acids. Among the 63 identified DoWRKY proteins, 10 contained two WRKY domains while the remaining members contained only one WRKY domain (Table 1). The highly conserved heptapeptide domain WRKYGQK was present in 56 DoWRKY proteins, whereas several variant heptapeptide domains were present in the remaining seven proteins, such as WRKYGKK in four proteins (DoWRKY24, DoWRKY30, DoWRKY68 and DoWRKY79), WRKYGEK in DoWRKY28 protein, WRKYGRD in DoWRKY6 protein, and WRKYATN in DoWRKY76 protein (Table 1). Among the 63 WRKY proteins, 52 of the DoWRKY proteins had a zinc-finger motif of the C-C-H-H type, while the remaining proteins had a variant zinc-finger motif of the C-C-H-C type (DoWRKY3, DoWRKY5, DoWRKY28, DoWRKY49, DoWRKY55, DoWRKY65, DoWRKY66, DoWRKY70, DoWRKY75 and DoWRKY78) and C-C-H-Y type (DoWRKY57) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Identified DoWRKY genes from D. officinale and their related information.

| Gene name | Annotation ID | ORF (aa) | Conserved motif | Zinc-finger type | Conserved motif number | Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DoWRKY1 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10130608 | 529 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH(N)/C-X5-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY7 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10115484 | 638 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY9 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10112830 | 434 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY12 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10109483 | 542 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY15 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10100432 | 549 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY20 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10094986 | 717 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY25 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10089661 | 611 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY32 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10077269 | 578 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY37 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10074853 | 731 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY39 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10074607 | 557 | WRKYGQK/WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH (N)/C-X4-C-X23-HXH (C) | 2 | I |

| DoWRKY62 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10044500 | 302 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | I |

| DoWRKY63 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10044501 | 353 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH | 1 | I |

| DoWRKY80 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10003356 | 330 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH | 1 | I |

| DoWRKY81 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10000561 | 135 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X22-HXH | 1 | 1 |

| DoWRKY2 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10129229 | 277 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X22-HXH | 1 | IIa |

| DoWRKY43 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10069437 | 309 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIa |

| DoWRKY73 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10020166 | 302 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIa |

| DoWRKY77 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10013350 | 225 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIa |

| DoWRKY42 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10070674 | 451 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIb |

| DoWRKY53 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10059328 | 570 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIb |

| DoWRKY69 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10025602 | 535 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIb |

| DoWRKY4 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10121280 | 262 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY10 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10112584 | 303 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY14 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10102564 | 316 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY26 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10089597 | 147 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY27 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10085956 | 256 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY40 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10073350 | 162 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY44 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10069083 | 617 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY48 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10063016 | 187 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY50 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10060580 | 158 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIc |

| DoWRKY18 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10095806 | 329 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IId |

| DoWRKY45 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10064360 | 159 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IId |

| DoWRKY52 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10059569 | 280 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IId |

| DoWRKY54 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10058347 | 149 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IId |

| DoWRKY64 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10043009 | 199 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IId |

| DoWRKY74 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10016910 | 331 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IId |

| DoWRKY31 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10079755 | 397 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIe |

| DoWRKY33 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10076351 | 444 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIe |

| DoWRKY35 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10075224 | 314 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIe |

| DoWRKY47 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10063175 | 396 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIe |

| DoWRKY51 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10059893 | 224 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIe |

| DoWRKY67 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10026080 | 350 | WRKYGQK | C-X5-C-X23-HXH | 1 | IIe |

| DoWRKY3 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10121855 | 293 | WRKYGQK | C-X3-C-X5-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY5 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10120404 | 329 | WRKYGQK | C-X7-C-X23-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY28 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10083557 | 182 | WRKYGEK | C-X7-C-X26-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY49 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10060697 | 274 | WRKYGQK | C-X7-C-X23-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY55 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10054889 | 348 | WRKYGQK | C-X7-C-X23-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY65 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10041878 | 294 | WRKYGQK | C-X7-C-X23-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY66 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10037978 | 253 | WRKYGQK | C-X7-C-X27-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY70 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10024898 | 365 | WRKYGQK | C-X7-C-X23-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY75 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10014237 | 264 | WRKYGQK | C-X7-C-X26-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY78 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10010985 | 295 | WRKYGQK | C-X7-C-X23-HXC | 1 | III |

| DoWRKY6 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10117096 | 194 | WRKYGRD | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY23 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10091977 | 320 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY24 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10091032 | 136 | WRKYGKK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY30 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10082894 | 198 | WRKYGKK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY57 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10051729 | 118 | WKKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXY | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY59 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10049096 | 141 | WNKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY60 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10049097 | 110 | WTKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY68 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10025631 | 195 | WRKYGKK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY72 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10023473 | 350 | WRKYGQK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY76 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10013560 | 196 | WRKYATN | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

| DoWRKY79 | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10007018 | 196 | WRKYGKK | C-X4-C-X23-HXH | 1 | NG |

Classification of DoWRKY proteins

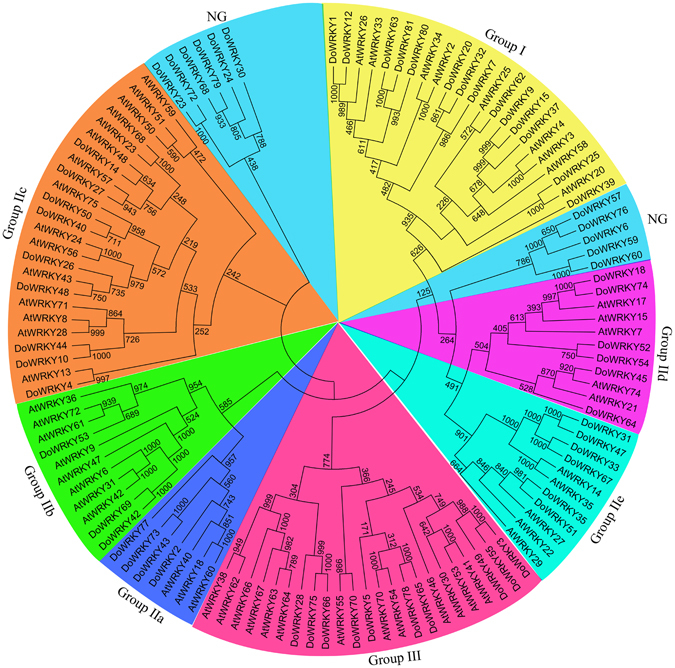

Based on the AtWRKY classification in A. thaliana 46, AtWRKY amino acid sequences from groups I, II or III were selected and downloaded from PlnTFDB (3.0, http://plntfdb.bio.uni-potsdam.de/v3.0/) to analyze the phylogenetic relationship between the selected AtWRKY proteins and the 63 DoWRKY proteins. The result show that the 63 DoWRKY proteins could be classified into three main groups corresponding to groups I, II and III and into two groups, which were named as the non-group (NG, Fig. 1). Among the 14 DoWRKY proteins in group I, 10 of which contained two conserved WRKY domains (WRKYGQK) and two zinc-finger motifs [C-X4-C-X22-HXH(N)/C-X5-C-X23-HXH(C)], the other four DoWRKY proteins (DoWRKY62, DoWRKY63, DoWRKY80 and DoWRKY81) contained only one WRKY domain (Table 1). Group II could be further divided into five subgroups, IIa, IIb, IIc, IId and IIe and contained 4, 3, 9, 6 and 6 DoWRKY members, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 1). All the DoWRKY proteins in group II contained a highly conserved WRKY domain and a zinc-finger structure, C-X4/5-C-X22/23-HXH. Ten DoWRKY proteins included in group III had a single WRKY domain and an alter zinc-finger motif C-C-H-C when compared with groups I and II (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Unrooted phylogenetic tree of D. officinale and Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY proteins. The 63 DoWRKY proteins and 58 AtWRKY proteins were aligned by ClustalX 2.0 to generate a phylogenetic tree using the Neighbor–Joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

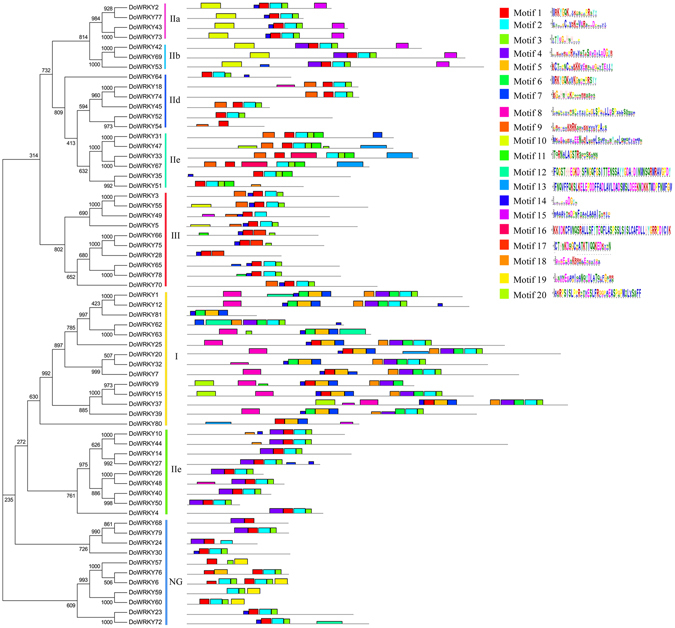

Motif composition of DoWRKY proteins

Generally, members shared similar motifs, indicating a similar function. To better understand the similarity and diversity of motifs of DoWRKY proteins, the conserved motifs of DoWRKY proteins were investigated using MEME online software (http://meme.nbcr.net/meme/cgi-bin/meme.cgi). Among the 20 identified motifs, both motif 1 and motif 6 contained the heptapeptide stretch WRKYGQK, which was regarded as a basic characteristic of the WRKY family. All of the DoWRKY proteins contained either motif 1 or motif 6, or both. Both motifs 2 and 3 had a zinc-finger structure at the N-terminal end and were similar to motifs 1 and 6 for the vast majority of DoWRKY proteins, except for DoWRKY9, −24, −28, −49, −54, 57, −63, −66, −75, −80 and −81 (Fig. 2). The DoWRKY proteins in the same group or subgroup usually had similar motifs, while the motifs in subgroups IIa and IIb were quite similar, with 5 of 6 motifs being the same (Fig. 2). Some motifs were unique in a group of DoWRKY proteins. For example, motifs 6 and 8 were unique within group I (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Visualization of the classification of DoWRKY proteins and the distribution of 20 predicted motifs in these proteins. The phylogenetic tree was inferred using the Neighbor–Joining method and 1000 bootstrap replicates with full-length of DoWRKY amino acid sequences by ClustalX 2.0 software. The conserved motifs were investigated by the MEME program.

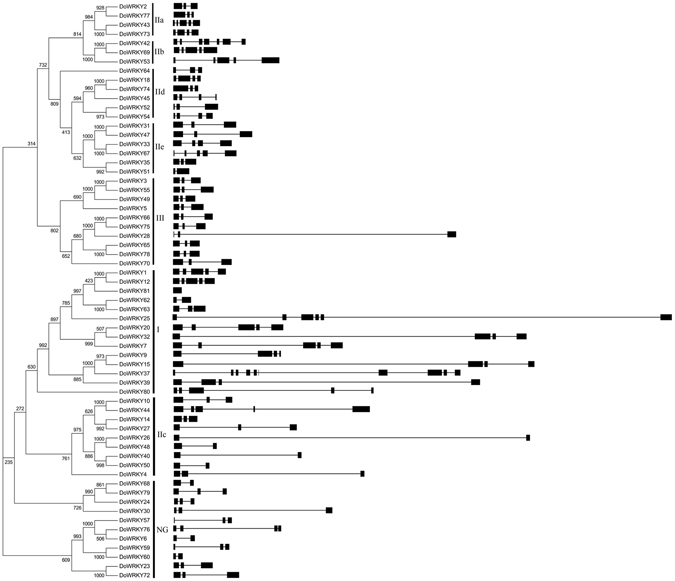

Exon–intron organization analysis of DoWRKY genes

To obtain insight into the structural features of DoWRKY genes, intron/exon distribution was analyzed, as it is perceived as providing a novel source of evolutionary information47. Among the 63 DoWRKY genes, 31 had three exons and two introns, 10 had five exons and four introns, nine had four exons and three introns, eight had two exons, while the remaining genes had one exon (DoWRKY81), six exons (DoWRKY25 and DoWRKY60), seven exons (DoWRKY42) and 10 exons (DoWRKY37) (Fig. 3). The DoWRKY genes that were classified into the same group usually shared a similar intron/exon composition. For example, all the DoWRKY genes in group III had three exons while genes in group II had an exon number that ranged from two to five exons, except for one gene that had seven exons (DoWRKY42). However, the number of exons in group I varied considerably, ranging from one to 10. This result indicates that exon loss and gain occurred in the groups I and II DoWRKY genes during evolution, which may lead to functional diversity of closely related WRKY genes.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis and structures of WRKY genes in D. officinale. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by ClustalX 2.0 with the Neighbor–Joining method and 1000 bootstrap replicates based on alignments of complete predicted DoWRKY protein sequences. In the gene structure diagram, black boxes and lines represent exons and introns, respectively.

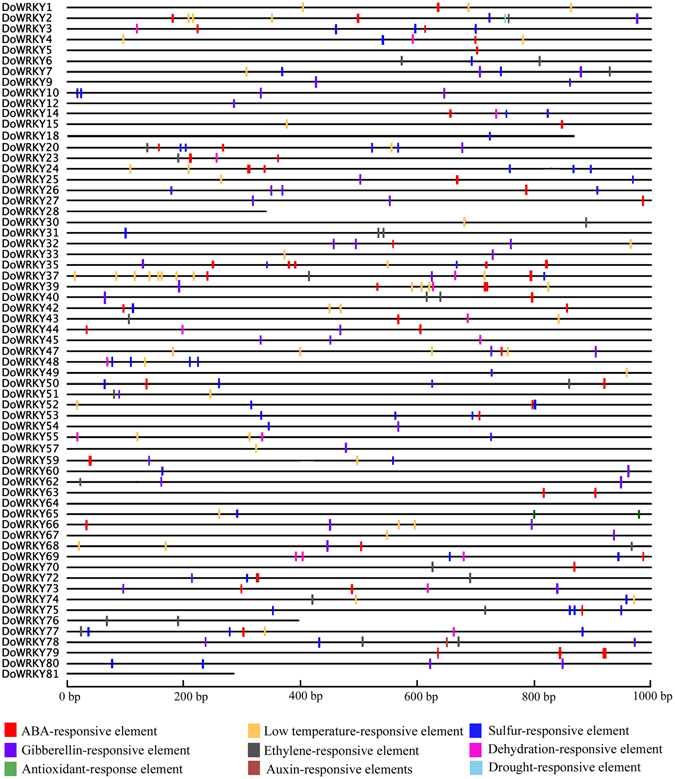

Stress-related regulatory elements in the putative promoters of DoWRKY genes

Cis-regulatory elements, which are usually restricted to 5′ upstream areas of genes, are the binding sites of TFs, and are responsible for transcriptional regulation48. Thus, the 1-k upstream regulatory regions of all the 63 DoWRKY genes were used to explore stress-related regulatory elements. As expected, an abundance of abscisic acid (ABA)-responsive elements was present in the promoters of most DoWRKY genes (Fig. 4). ABA is known to be a vital mediator of responses in plants to various adverse environmental conditions, including cold, salinity, and drought49. Interestingly, low temperature-responsive elements were the second largest group of elements among the promoters of DoWRKY genes, which would typically drive genes in response to low temperatures (Fig. 4). DoWRKY37 harbored 9 low temperature-responsive elements in its 1-k upstream regulatory region (Fig. 4). Sulfur-responsive elements, which are known to regulate the sulfur status in plants, were also abundant, suggesting that the DoWRKY genes play a role in maintaining the sulfur status of Dendrobium plants. Drought-responsive elements and auxin-responsive elements were rarely present in the detected sequences of the 1-k upstream regulatory region, and only DoWRKY 2 and DoWRKY 72, −78 contained one drought-responsive element and one auxin-responsive element, respectively (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Prediction of cis-responsive elements in the 1-k upstream regulatory regions of DoWRKY genes. Different cis-responsive elements are represented by different colored boxes.

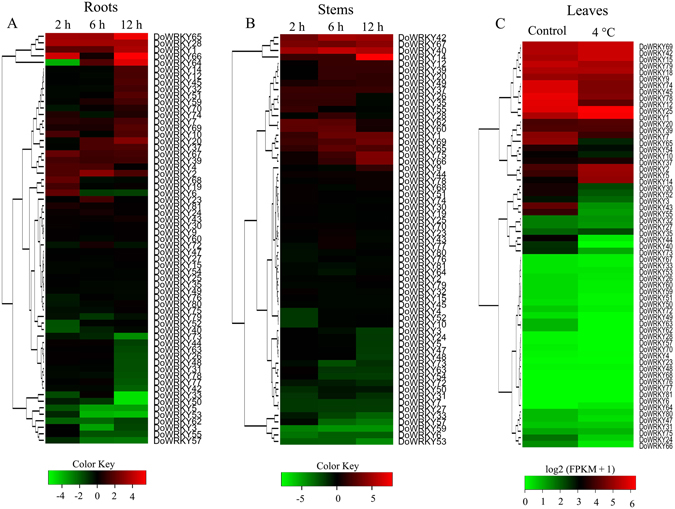

Expression of DoWRKY genes under cold stress in D. officinale

Based on an understanding of the abundance of low temperature-responsive elements in the 1-k upstream regulatory regions of DoWRKY genes, a cold stress treatment was applied to D. officinale seedlings in order to obtain their expression profiles of these genes. The expression profiles of DoWRKY genes under cold stress (4 °C) in roots and stems were determined by qPCR while that of leaves was determined by RNA-seq. The data demonstrated that a large number of DoWRKY genes were regulated by low temperature in roots and stems. At least two genes (DoWRKY1 and DoWARKY14) were up-regulated in all the organs in which DoWRKY genes were detected, namely roots, stems and leaves, while no DoWRKY genes were down-regulated in these organs. Six DoWRKY genes were up-regulated (DoWRKY1, -2, -28, -39, -65 and -67), while DoWRKY5 and DoWRKY62 were down-regulated at all detected time points in roots (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table 2). As shown in Fig. 5B and Supplementary Table 3, the expression levels of DoWRKY1, -14, -37, -40, -42, -65, -67 and -69 increased at 2 h, 6 h and 12 h in stems. However, just four DoWRKY genes (DoWRKY1, -2, -5 and -14) were up-regulated under low temperature for 20 h, assessed by RNA-seq analysis (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 5.

Expression profiles of DoWRKY genes with an expression pattern in roots, stems and leaves of Dendrobium officinale under cold (4 °C) stress. (A and B) Clustering of DoWRKY genes according to their expression profiles in roots and stems after cold treatments at four time points (0, 2, 6 and 12 h). The expression of the 63 DoWRKY genes was assessed based on an analysis of qPCR results. (C) Heat map showing expression pattern of DoWRKY genes in leaves under cold stress for 20 h. The Y-axis represents the value of the relative expression level [log 2 (mean of FPKM + 1)].

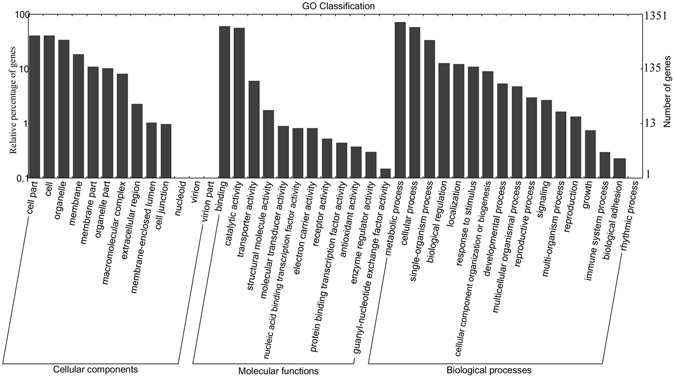

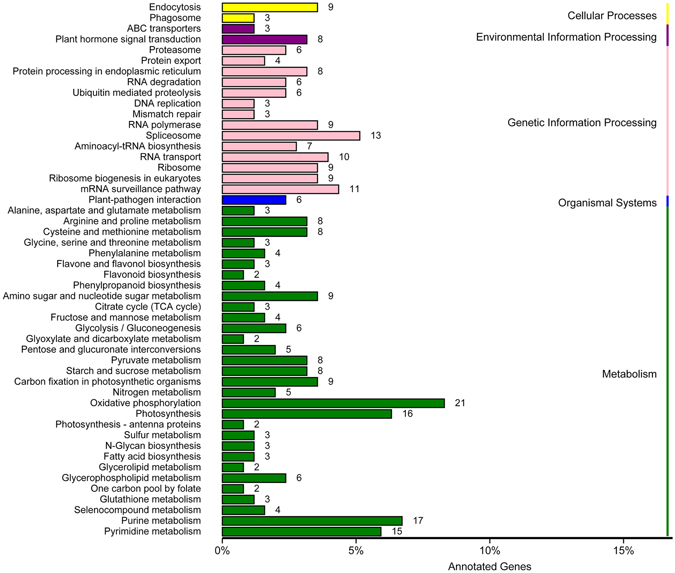

Identification and annotation of potential WRKY target genes

From a total of 34,417 putative gene promoters from D. officinale were obtained, 10,757 genes contained at least one W-box element in their putative promoters, while 7127 and 3515 genes contained at least two and at least three W-box elements, respectively in their putative promoters. The 3515 genes with at least three W-box elements in their putative promoters were used for further annotation. Among the 3515 genes, 2504 were related to other known genes or proteins in the Nr database, 1305 were annotated in GO based on sequence homologies, and just 353 mapped to reference canonical pathways in the KEGG database. For the GO classification, the WRKY target genes were categorized into 42 functional groups under three main categories: biological processes, cellular components and molecular functions (Fig. 6). For the analysis of biological pathways, a total of 253 genes were assigned to 88 KEGG pathways, including four main categories: ‘metabolism’, ‘environmental information processing’, ‘genetic information processing’ and ‘cellular processes’ (Fig. 7). More genes were classified under ‘metabolism’ than in the three other main categories.

Figure 6.

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of WRKY target genes in D. officinale. Categories pertaining to cellular components, molecular functions and biological processes were defined by GO classification.

Figure 7.

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis of WRKY target genes in D. officinale. KEGG pathway consists of graphical diagrams contained four main categories: ‘metabolism’ (green), ‘genetic information processing’ (pink), ‘environmental information processing’ (purple), ‘cellular processes’ (yellow) and ‘organismal systems’ (blue).

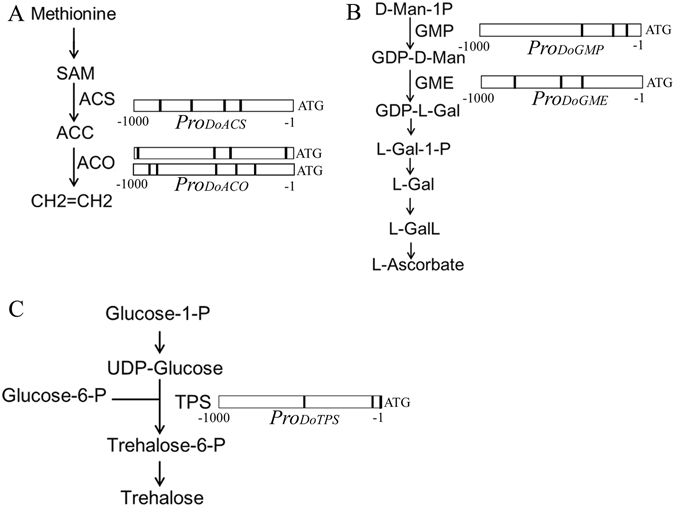

Stress metabolic pathways of potential WRKY target genes

The metabolic pathways related to stress responses in plants are shown in Fig. 8. One 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase (ACS) and two 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid oxidase (ACO) genes had 3–4 W-box elements in their putative promoters. Both ACS and ACO are involved in the ethylene biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 8A). GDP-D-mannose pyrophosphorylase (GMP) and GDP-mannose 3,5-epimerase (GME), which are both involved in L-Ascorbate biosynthesis, had three W-box elements in their putative promoters (Fig. 8B). The 1-k upstream regulatory region of the trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS) gene contained three W-box elements (Fig. 8C). These results indicate that DoWKRY genes might play a role in stress responses by regulating stress-related gene expression in D. officinale.

Figure 8.

Analysis of the WRKY target genes in the biosynthetic pathway of ethylene, L-Ascorbate and trehalose. (A) One gene encoding ACC synthase (ACS) and two genes encoding ACC oxidases (ACO) contained multiple W-box elements in their 1-k upstream regulatory regions. SAM, S-adenoysl-methionine; ACC 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid. (B) Visualization of WRKY target genes in the L-Ascorbate pathway. GMP, GDP-Man pyrophosphorylase; GME, GDP-Man-3,5-epimerase. (C) One gene encoding trehalose-6-phosphate synthase (TPS) has three W-box elements in its 1-k upstream regulatory region.

Polysaccharide metabolism-related genes may be WRKY target genes

Among potential WRKY target genes with at least three W-box elements, a number of genes related to polysaccharide metabolism were found. For example, glycosyltransferases such as glucosyltransferase, xylosyltransferase, galactosyltransferase, cellulose synthase and mannan synthase, which are involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis, contained 3–7 W-box elements in their 1-k upstream regulatory regions (Table 2). Golgi-localized nucleotide sugar transporters are essential for polysaccharide biosynthesis by providing sugars to the Golgi apparatus50. DoWRKY genes may also regulate the transcription of sugar transporter genes (Dendrobium_GLEAN_10110460, UDP-sugar transporter; Dendrobium_GLEAN_10127692, GDP-mannose transporter) because W-box elements were found in their putative promoter (Table 2). Mannan mannosidases and glucan glucosidases containing 3–12 W-box elements in their 1-k upstream regulatory regions were identified (Table 2), suggesting that DoWRKY genes might regulate the hydrolysis of polysaccharides in D. officinale. The first WRKY TF was found to bind to the 5′ upstream regions of β-amylase and suppress the expression of β-amylase mRNAs7. In this study, W-box elements were also found in the 1-k upstream regulatory regions of amylases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Identified polysaccharide metabolism-related genes from WRKY target genes and their related information.

| Function | Protein classes | Annotation ID | W-box number | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polysaccharide biosynthesis | Glucosyltransferase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10093863 | 3 | −106, −33, −127 |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10093854 | 3 | −260, −312, −168 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10034225 | 3 | −905, −49, −110 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10037085 | 3 | −700, −498, −366 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10004757 | 3 | −767, −95, −946 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10114838 | 3 | −449, −46, −580 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10101470 | 3 | −304, −741, −416 | ||

| Xylosyltransferase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10043111 | 4 | −455, −843, −793, −725 | |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10090448 | 3 | −132, −57, −85 | ||

| Galactosyltransferase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10089526 | 3 | −123, −730, −961 | |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10090448 | 3 | −132, −57, −85 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10011963 | 5 | −621, −825, −106, −663, −11 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10125164 | 3 | −628, −597, −585 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10117276 | 5 | −928, −582, −220, −158, −304 | ||

| Cellulose synthase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10105279 | 3 | −666, −910, −132 | |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10115475 | 3 | −79, −307, −234 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10037286 | 3 | −366, −531, −157 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10023561 | 3 | −156, −931, −534 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10061727 | 3 | −280, −596, −242 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10064843 | 7 | −577, −516, −628, −536, −857, −527, −127 | ||

| Mannan synthase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10127097 | 3 | −848, −286, −991 | |

| Sugar transporter | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10110460 | 3 | −485, −145, −95 | |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10127692 | 3 | −425, −100, −420 | ||

| Polysaccharide hydrolysis | Mannan mannosidase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10059324 | 4 | −136, −391, −784, −369 |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10032958 | 12 | −920, −620, −602, −267, −667, −584, −679, −809, −359, −405, −592, −508 | ||

| Glucan glucosidase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10014101 | 9 | −763, −915, −501, −475, −604, −814, −788, −730, −567 | |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10108908 | 3 | −271, −536, −41 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10076876 | 3 | −471, −580, −9 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10014101 | 9 | −763, −915, −501, −475, −604, −814, −788, −730, −567 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10108908 | 3 | −271, −536, −41 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10076876 | 3 | −471, −580, −9 | ||

| Xyloglucan hydrolase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10031220 | 4 | −28, −187, −344, −419 | |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10116796 | 3 | −171, −467, −857 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10095975 | 3 | −299, −32, −95 | ||

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10059366 | 4 | −883, −778,−808, −686 | ||

| Amylase | Dendrobium_GLEAN_10097224 | 3 | −146, −937, −909 | |

| Dendrobium_GLEAN_10053987 | 4 | −781, −251, −961, −177 |

Discussion

Identification and structural conservation of DoWRKY proteins

The members of WRKY genes range from 48 (Carica papaya) to 202 (Zea mays) in higher plants (http://plntfdb.bio.uni-potsdam.de/v3.0/fam_mem.php?family_id=WRKY). The number of WRKY genes is not apparently correlated with genome size. For example, only 48 WRKY genes were identified in C. papaya, which has a genome of 372 megabases (Mb), while A. thaliana has over 88 members of WRKY genes and a compact 135 Mb genome51, 52. D. officinale has de novo assembled 1.35 gigabytes (Gb) of genome sequences32 and only 63 Nr WRKY genes were found. As described in the results, the WRKY genes in D. officinale can be divided into three main groups based on a phylogenetic analysis, while 11 of these 63 genes belong to none of the three main groups and are instead subdivided into two subgroups. Group IV or NG were also present in other plants, including rice (Oryza sativa)6 and grapevine (Vitis vinifera)15. The WRKY proteins contain one or two highly conserved heptapeptide WRKYGQK and a zinc-finger structure6. Of the 63 DoWRKY proteins, at least one contained a conserved heptapeptide WRKYGQK or variants of WRKYGQK. The WRKY proteins have mismatched amino acids in the highly conserved WRKYGQK sequence, as has been observed in many plant species such as carrot (Daucus carota)16 and black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa)53.

Correlation between the number of W-box elements and the reliability of target genes

An electrophoresis mobility shift assay (EMSA) or yeast one-hybrid system analysis demonstrated that the WRKY TF recombinant protein can bind to the W-box sequence but not to a mutated version of the W-box sequence54–57. However, the WRKY protein from Boea hygrometrica bound efficiently to the BhGolS1 promoter with at least two W-box elements, but showed a relatively lower affinity with a single W-box element in the BhGolS1 promoter after yeast one-hybrid system analysis57. A CaWRKY protein showed differences in binding affinity between probes that contained one or two W-box elements21. AtWRKY18 from Arabidopsis thaliana can only bind to one of three W-box elements but is unable to bind to the other two W-box elements in the AtABI4 promoter58. This suggests that there is a selective affinity of different W-box elements by WRKY protein while the number of W-box elements is correlated with the reliability of putative WRKY target genes.

DoWRKY genes play important roles in response to abiotic stresses

The number of low temperature-responsive elements (Fig. 4) that were present in most promoters of DoWRKY genes indicated that expression of these genes may be regulated by low temperature. Seventeen DoWRKY genes were inducible by low temperature in the roots of D. officinale (Fig. 5). Numerous studies have shown that a number of genes from the WRKY family are inducible by cold stress15, 59, 60. The conserved WRKY domain is broadly considered as a crucial element, which usually binds to the W-box elements in the promoter of the target gene to modulate transcription. The promoters of ethylene, L-Ascorbate and trehalose pathway genes contained W-box elements in D. officinale, suggesting that these genes may be regulated by WRKY TFs and their products may protect plants from adverse environments. Moreover, many stress-related genes were found to have W-box elements, including ethylene-responsive TFs, NAC TFs, dehydration-responsive element-binding proteins, disease resistance proteins, heavy metal transport/detoxification protein and peroxidases (Supplementary Table 5). Genes from the WRKY family confer multiple abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic plants61, 62.

The regulation of carbohydrate metabolism by DoWRKY proteins

The first WRKY TF (SPF1) was identified in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) where it was shown to act as a negative regulator of β-amylase7. Similarly, a WRKY protein inhibited the expression of α-amylase genes, suggesting that the WRKY gene acts as a negative regulator of α-amylase genes63, 64. In this study, two amylase genes contained W-box elements in their 1-k upstream regulatory regions may regulate by DoWRKY TFs (Table 2). Cell walls are mainly composed of cellulose, hemicelluloses and lignin65. Six cellulose synthases and 14 glycosyltransferases, containing 3–7 W-box elements in their 1-k upstream regulatory regions, were identified in this study (Table 2). Studies have shown that WRKY proteins act as negative regulators for secondary wall formation. For example, atwrky13 mutants exhibited a weaker stem with fewer sclerenchyma cells and vascular bundles, and thinner stems66. The WRKY13 protein can bind to the NST2 genes’ promoter, which belongs to the NAC family that regulates secondary wall biosynthesis66. The mutants of WRKY TFs from Medicago truncatula and A. thaliana can cause secondary wall thickening in pith and are negative regulators of secondary wall formation67. A recent study showed that PtrWRKY19, a homolog of A. thaliana WRKY12 in Populus trichocarpa, encoded a protein located in the nucleus and functioned as a transcriptional repressor of lignin biosynthesis-related genes68. Thus, WRKY TFs might function as negative regulators of carbohydrate metabolism.

In conclusion, a total of 63 WRKY genes were identified from an orchid plant, D. officinale. The classification and conserved domain of DoWRKY proteins, as well as stress-responsive elements in the promoters of DoWRKY genes were analyzed. Seventeen of the 63 DoWKRY genes were inducible by cold stress, indicating that they may play a role in the cold stress response of D. officinale. The WRKY target genes were investigated. Multiple W-box elements were observed in the promoters of stress-related genes and in genes related to polysaccharide metabolism, suggesting that DoWRKY genes may be involved in the regulation of abiotic stress response as well as in polysaccharide metabolism.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Yanping Lei (Genepioneer Biotechnologies, Nanjing, China) for drawing Figs 6 and 7. This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province Projects (Grant number 2016A030310012), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (Grant number 201704020192) and Science and Technology Service Network Initiative of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant number KFJ-EW-STS-118).

Author Contributions

J.D. supervised the project. C.H. conceived the research and designed the experiments. X.P. and C.H. conducted qPCR. J.Z. cultured and provided the experimental materials. M.L. performed the bioinformatics analyses. C.H. J.A.T.d.S., J.T. and J.L. collectively interpreted the results and wrote all drafts of the manuscript. All 8 authors approved the final draft for submission and take full public responsibility for the content of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07872-8

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Riechmann JL, et al. Arabidopsis Transcription factors: genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science. 2000;290:2105–2110. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends in Plant Science. 2000;5:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rushton PJ, Somssich IE, Ringler P, Shen QJ. WRKY transcription factors. Trends in Plant Science. 2010;15:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamasaki K, et al. Structural basis for sequence-specific DNA recognition by an Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:7683–7691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinerson CI, Rabara RC, Tripathi P, Shen QJ, Rushton PJ. The evolution of WRKY transcription factors. BMC Plant Biology. 2015;15:66. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0456-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross CA, Liu Y, Shen QJ. The WRKY gene family in rice (Oryza sativa) Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2007;49:827–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00504.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishiguro S, Nakamura K. Characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel DNA-binding protein, SPF1, that recognizes SP8 sequences in the 5′ upstream regions of genes coding for sporamin and β-amylase from sweet potato. Molecular and General Genetics MGG. 1994;244:563–571. doi: 10.1007/BF00282746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu H, Ni Z, Yao Y, Guo G, Sun Q. Cloning and expression profiles of 15 genes encoding WRKY transcription factor in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Progress in Natural Science. 2008;18:697–705. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2007.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou QY, et al. Soybean WRKY-type transcription factor genes, GmWRKY13, GmWRKY21, and GmWRKY54, confer differential tolerance to abiotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2008;6:486–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang H, et al. Rice WRKY4 acts as a transcriptional activator mediating defense responses toward Rhizoctonia solani, the causing agent of rice sheath blight. Plant Molecular Biology. 2015;89:157–171. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao J, et al. Cloning and expression analysis of transcription factor gene DoWRs. China Journal of Chinese Materia Medica. 2015;40:2807–2813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling J, et al. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY gene family in Cucumis sativus. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:471. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tripathi P, et al. The WRKY transcription factor family in Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:270. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song, H., Wang, P., Nan, Z. & Wang, X. The WRKY transcription factor genes in Lotus japonicus. InternationalJournal of Genomics2014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Wang L, et al. Genome-wide identification of WRKY family genes and their response to cold stress in Vitis vinifera. BMC Plant Biology. 2014;14:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li M-Y, et al. Genomic identification of WRKY transcription factors in carrot (Daucus carota) and analysis of evolution and homologous groups for plants. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:23101. doi: 10.1038/srep23101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the WRKY gene family in cassava. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2016;7:25. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang, Y. et al. Functional analysis of structurally related soybean GmWRKY58 and GmWRKY76 in plant growth and development. Journal of Experimental Botany, erw252 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Zhou X, Jiang Y, Yu D. WRKY22 transcription factor mediates dark-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Molecules and Cells. 2011;31:303–313. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0047-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding ZJ, et al. WRKY41 controls Arabidopsis seed dormancy via direct regulation of ABI3 transcript levels not downstream of ABA. The Plant Journal. 2014;79:810–823. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park, C.-J. et al. A hot pepper gene encoding WRKY transcription factor is induced during hypersensitive response to Tobacco mosaic virus and Xanthomonas campestris. Planta223, 168–179 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Lippok B, et al. Expression of AtWRKY33 encoding a pathogen-or PAMP-responsive WRKY transcription factor is regulated by a composite DNA motif containing W box elements. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2007;20:420–429. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-4-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karim A, et al. Isolation and characterization of a subgroup IIa WRKY transcription factor PtrWRKY40 from Populus trichocarpa. Tree Physiology. 2015;35:1129–1139. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpv084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merz PR, et al. The transcription factor VvWRKY33 is involved in the regulation of grapevine (Vitis vinifera) defense against the oomycete pathogen Plasmopara viticola. Physiologia Plantarum. 2015;153:365–380. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, et al. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant abiotic stresses. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2012;1819:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding ZJ, et al. Transcription factor WRKY46 regulates osmotic stress responses and stomatal movement independently in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal. 2014;79:13–27. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang F, et al. GmWRKY27 interacts with GmMYB174 to reduce expression of GmNAC29 for stress tolerance in soybean plants. The Plant Journal. 2015;83:224–236. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niu C-F, et al. Wheat WRKY genes TaWRKY2 and TaWRKY19 regulate abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant, Cell & Environment. 2012;35:1156–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, et al. Expression of TaWRKY44, a wheat WRKY gene, in transgenic tobacco confers multiple abiotic stress tolerances. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2015;6:615. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teixeira da Silva JA, Ng TB. The medicinal and pharmaceutical importance of Dendrobium species. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2017;101:2227–2239. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai J, et al. The genome sequence of the orchid Phalaenopsis equestris. Nature Genetics. 2015;47:65–72. doi: 10.1038/ng.3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan L, et al. The genome of Dendrobium officinale illuminates the biology of the important traditional Chinese orchid herb. Molecular Plant. 2015;8:922–934. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang, G.-Q. et al. The Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. genome sequence provides insights into polysaccharide synthase, floral development and adaptive evolution. Scientific Reports6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio-assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Plant Physiology. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larkin, M. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics23, 2947–2948 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Hu B, et al. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higo K, Ugawa Y, Iwamoto M, Korenaga T. Plant cis-acting regulatory DNA elements (PLACE) database: 1999. Nucleic Acids Research. 1999;27:297–300. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ülker B, Somssich IE. WRKY transcription factors: from DNA binding towards biological function. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2004;7:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen F, Li j, Zhang G, Liu Q. The mechanism and application of yeast one-hybrid system. Progress in Biotechnology. 2001;21:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye J, et al. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:W293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He C, et al. Identification of genes involved in biosynthesis of mannan polysaccharides in Dendrobium officinale by RNA-seq analysis. Plant Molecular Biology. 2015;88:219–231. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0316-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu, Z.-G. et al. Insights from the cold transcriptome and metabolome of Dendrobium officinale: global reprogramming of metabolic and gene regulation networks during cold acclimation. Frontiers in Plant Science7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Kim D, et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biology. 2013;14:R36. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nature Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu K-L, Guo Z-J, Wang H-H, Li J. The WRKY family of transcription factors in rice and Arabidopsis and their origins. DNA Research. 2005;12:9–26. doi: 10.1093/dnares/12.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yandell M, et al. Large-scale trends in the evolution of gene structures within 11 animal genomes. PLOS Computational Biology. 2006;2:113–125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wittkopp PJ, Kalay G. Cis-regulatory elements: molecular mechanisms and evolutionary processes underlying divergence. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;13:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nrg3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finkelstein R. Abscisic acid synthesis and response. The Arabidopsis Book. 2013;11:e0166. doi: 10.1199/tab.0166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang B, et al. Golgi nucleotide sugar transporter modulates cell wall biosynthesis and plant growth in rice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2011;108:5110–5115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016144108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Initiative AG. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796. doi: 10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ming R, et al. The draft genome of the transgenic tropical fruit tree papaya (Carica papaya Linnaeus) Nature. 2008;452:991–996. doi: 10.1038/nature06856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He H, et al. Genome-wide survey and characterization of the WRKY gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Plant Cell Reports. 2012;31:1199–1217. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Z-L, et al. A rice WRKY gene encodes a transcriptional repressor of the gibberellin signaling pathway in aleurone cells. Plant Physiology. 2004;134:1500–1513. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.034967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng L, et al. A WRKY gene from Tamarix hispida, ThWRKY4, mediates abiotic stress responses by modulating reactive oxygen species and expression of stress-responsive genes. Plant Molecular Biology. 2013;82:303–320. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0063-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zheng Z, Qamar SA, Chen Z, Mengiste T. Arabidopsis WRKY33 transcription factor is required for resistance to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. The Plant Journal. 2006;48:592–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Z, et al. A WRKY transcription factor participates in dehydration tolerance in Boea hygrometrica by binding to the W-box elements of the galactinol synthase (BhGolS1) promoter. Planta. 2009;230:1155. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-1014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Z-Q, et al. Cooperation of three WRKY-domain transcription factors WRKY18, WRKY40, and WRKY60 in repressing two ABA-responsive genes ABI4 and ABI5 in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63:6371–6392. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sahin-Cevik M. A WRKY transcription factor gene isolated from Poncirus trifoliata shows differential responses to cold and drought stresses. Plant Omics. 2012;5:438. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim C-Y, et al. Functional analysis of a cold-responsive rice WRKY gene, OsWRKY71. Plant Biotechnology Reports. 2016;10:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s11816-015-0383-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chu X, et al. The cotton WRKY gene GhWRKY41 positively regulates salt and drought stress tolerance in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0143022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dai, X., Wang, Y. & Zhang, W.-H. OsWRKY74, a WRKY transcription factor, modulates tolerance to phosphate starvation in rice. Journal of Experimental Botany, erv515 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Rushton PJ, Macdonald H, Huttly AK, Lazarus CM, Hooley R. Members of a new family of DNA-binding proteins bind to a conserved cis-element in the promoters of α-Amy2 genes. Plant Molecular Biology. 1995;29:691–702. doi: 10.1007/BF00041160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xie Z, Zhang Z-L, Hanzlik S, Cook E, Shen QJ. Salicylic acid inhibits gibberellin-induced alpha-amylase expression and seed germination via a pathway involving an abscisic-acid-inducible WRKY gene. Plant Molecular Biology. 2007;64:293–303. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhong, R. & Ye, Z.-H. Secondary cell walls: biosynthesis, patterned deposition and transcriptional regulation. Plant and Cell Physiology, pcu140 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Li W, Tian Z, Yu D. WRKY13 acts in stem development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Science. 2015;236:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang H, et al. Mutation of WRKY transcription factors initiates pith secondary wall formation and increases stem biomass in dicotyledonous plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2010;107:22338–22343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016436107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yang L, et al. PtrWRKY19, a novel WRKY transcription factor, contributes to the regulation of pith secondary wall formation in Populus trichocarpa. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:18643. doi: 10.1038/srep18643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.