Abstract

Background

Tennis elbow is an overuse injury affecting people performing repetitive forearm movements. It is a soft tissue disorder that causes significant disability and pain.

The aim of the study was to establish that an intramuscular steroid injection is effective in the short-term pain relief and functional improvement of tennis elbow. The severity of pain at the injection site was monitored to determine whether the intramuscular injection is better tolerated than the intralesional injection.

Methods and results

19 patients, who had no treatment for tennis elbow in the preceding 3 months, were recruited from Whipps Cross University Hospital, London, and were randomised to receive either 80 mg of intramuscular Depo-Medrone or 40 mg of intralesional Depo-Medrone injection. Blinding proved difficult as the injection sites differed and placebo arms were not included in the study. A Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE) Questionnaire and a 10-point Likert scale were used to assess primary outcome. Six weeks after the treatment, there was a reduction in pain, improvement in function and total PRTEE scores in both intramuscular and intralesional groups (p=0.008) using a 95% CI for mean treatment difference of −26 to +16 points. A statistically significant result (p=0.001) in favour of intramuscular causing less pain at the injection site was noted.

Conclusion

Non-inferiority of intramuscular to intralesional injections was not confirmed; however, the intramuscular injection proved to be effective in reducing tennis elbow-related symptoms and was found less painful at the site of injection at the time of administration.

Trial registration number

EUDRACT Number: 2010-022131-11.

REC Number: 10/H0718/76 (NRES, Central London REC 1).

Keywords: Sports medicine, Tennis elbow, Tendinopathy

Key messages.

What is already known on this topic?

Corticosteroids are potent anti-inflammatory and pain-modulating drugs and may act through both local and systemic mechanisms.

Multiple studies and a systematic review suggest that a steroid injection for tennis elbow improves many short-term (6-week) outcome measures including pain and disability.

Pain and disability associated with tennis elbow typically follows a self-limiting course of 12 months but this may pose a potentially significant socioeconomic impact on individuals.

What this study adds?

Both intralesional and intramuscular corticosteroid injections have been shown to be effective and safe in the treatment of tennis elbow.

Non-inferiority of the intramuscular steroid injection compared with the intralesional steroid injection could not be inferred.

Intramuscular steroid injection was shown to be less painful at the site and time of injection compared with an intralesional injection.

This study did not include a sham group, so whether either treatment is superior to placebo could not be determined.

Introduction

Tennis elbow, also known as lateral epicondylopathy,1 2 is the most common injury in patients seeking medical attention for elbow pain. It can be defined as an overuse injury occurring at the lateral side of the elbow where the common extensors originate from the lateral epicondyle.1 2 The pathology has been described as a degenerative process secondary to tensile overuse and possible angiofibroblastic changes.1 2 People at risk are typically those in occupations who require manual tasks with strenuous or repetitive forearm movement.3 The injury is commonly associated with playing tennis and other racquet sports.4 5

Typical symptoms include a weakened grip strength and narrowed range of movement with the elbow in extension so daily activities become restricted.3–5 It has a 1%–3% incidence in the general population.5 6

As a self-limiting condition, the management of lateral epicondylopathy tends to rely on a conservative approach. Graduated strengthening and stretching exercises7 as well as rest and forearm bracing can alleviate pain. There is no consistency in the advice offered by primary care physicians and specialists which may reflect in the wide range of treatments shown to have benefit.8–10 As an additional step contributory biomechanical factors such as improper use of special equipment or inadequate working and exercising technique should be addressed and corrected. In secondary care, a steroid injection about the lateral epicondyle is often offered.11–13 The rationale behind this is unclear. There is evidence to show this improves short-term (6-week) outcome measures, including pain to allow a quicker return to work.14–16 Repeat injections however are not recommended as these, although scarcely reported can cause tendon rupture.9

The administration of intralesional steroids requires training. It is commonly performed by general practitioners (GPs) however rarely under ultrasound (US) guidance and can be painful and potentially harmful causing metabolic disturbance and lipoid deposition to extra-articular soft tissues leading to weakening and consequent tendon damage.17 In rotator cuff tendinosis, a study comparing a local intralesional subacromial US-guided steroid injection with a systemic steroid injection into the gluteal muscle showed no important differences in short-term outcome.18 This suggests that an intramuscular injection is as effective as an intralesional injection for rotator cuff disease. If this effect is translatable to lateral epicondylopathy, there are a number of potential implications: GPs would be able to administer systemic steroids as intramuscular injections without training; tertiary referrals and costs would be reduced and the procedure would cause less distress and pain to patients.

Methods

The study is a prospective, randomised, controlled trial. It was undertaken after ethical approval from Central London REC 1. Patients were recruited between December 2010 and December 2011 from the Rheumatology/Sports Medicine Clinic at Whipps Cross University Hospital, London.

Study design and population

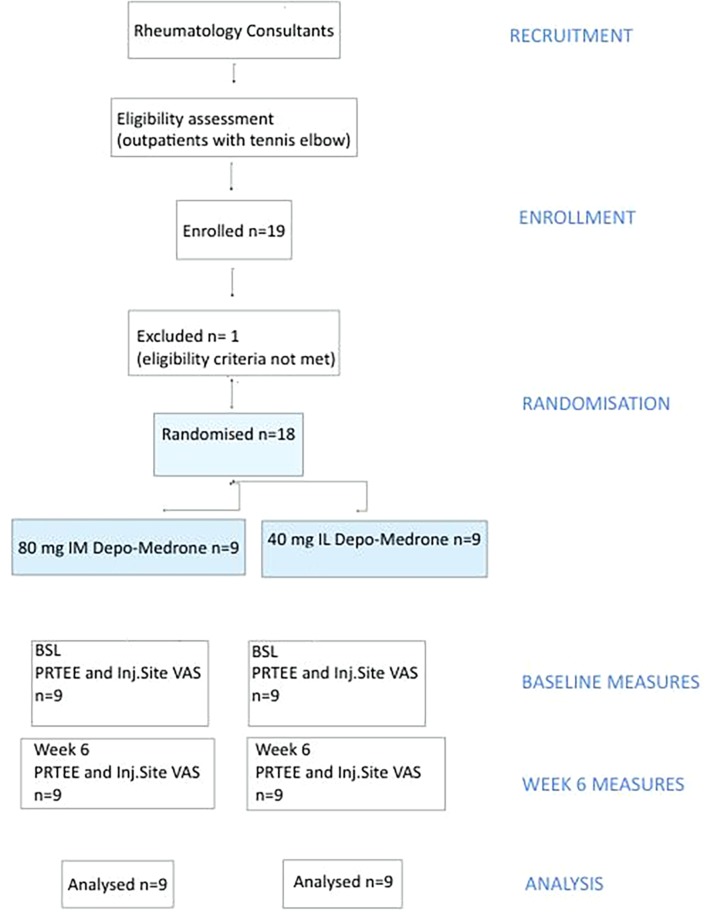

Patients with symptoms of pain on palpation of the common extensor origin and pain reproduced on resisted extension of the wrist with the elbow extended were eligible to participate provided they had no treatment in the preceding 3 months. All participants were aged over 18 years (figure 1). A total of 19 patients were randomised (table 1). One patient was withdrawn from the final analysis as they had an intralesional injection 11 weeks earlier.

Figure 1.

Study design and population. BSL, baseline; PRTEE, Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation; VAS, visual analogue score.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of recruited patients

| Female (n) | Male (n) | Age ±SD | Right arm | Left arm | Dominant arm (%) | |

| Intramuscular | 5 | 4 | 45±6.5 | 7 | 2 | 7 (77) |

| Intralesional | 5 | 4 | 43.5±12.2 | 6 | 3 | 8 (88) |

Exclusion criteria included the following: trauma to the affected elbow in the preceding 6 weeks; patients with a history of elbow instability; previous elbow surgery; bilateral symptoms; other pathology involving the affected upper limb; coexisting cervical spine pathology; physiotherapy or steroid injection for the presenting condition within 3 months; patients already on oral/systemic steroids; patients with contraindications to injection therapy including patients with bleeding diatheses or on anticoagulant therapy, local or systemic infection, history of hypersensitivity to local anaesthetics, poorly controlled diabetes, immunosuppression, pregnancy or breast feeding, psychiatric diagnosis and prosthetic elbow joint.

Study protocol

Patients were consulted by the investigators and were provided with an information sheet outlining the aims and the methods of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients who consented to the study were randomised the following way: sealed envelopes were prepared, containing equal number of a tokens for intralesional injection and intramuscular injections. The envelopes were shuffled after which the investigators randomly chose an envelope each time patients agreed to participate in the trial.

Treatment

All patients were given a patient information leaflet (appendix 1) and were further instructed to augment favourable outcome. Patients were asked to avoid repetitive elbow extension, forceful elbow activities or movements that provoke pain.

Ergonomic impact factors derived from sporting or working activities were discussed and self-management in the form of rest/avoidance suggested, although absolute rest of the arm was not advocated. In addition, the patients were advised to gradually increase activity once acute pain had settled and some basic progressive exercises were explained (appendix 1).

The consented patients were allocated to receive either 1 mL of 40 mg intralesional Depo-Medrone or 2 mL of 80 mg intramuscular Depo-Medrone. The technique used was a conventional pepper pot technique in case of the intralesional procedure involving multiple insertions of the injecting needle around the teno-periosteum junction.19 This was performed through multiple movements of the inserted needle aiming to infiltrate the epicondylar region from different angles.20 The intramuscular injections were given into the gluteal muscle.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were pain severity and functional disability as assessed by a Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE) Questionnaire (appendix 2).21 22 This was assessed before the injection and then 6 weeks later. The PRTEE is an instrument specifically developed for the use in tennis elbow and has been increasingly employed in research. It contains 15 items: 5 items addressing pain and 10 concerned with functional deficit. For each item, the respondent uses a 0–10 numerical scale to rate the average pain or difficulty they have experienced over the previous week while carrying out various specific activities. The marking system ensures pain and function are weighted equally in the total score. A total score out of 100 can then be computed from the obtained pain and disability score. Another primary outcome was pain severity at the site of injection as assessed by a 10-point Likert scale.23 This was assessed, immediately after administration, 24 and 48 hours later.

The secondary results contained the rate and nature of complications and adverse events. Immediate and late complications including infection, local skin atrophy and facial flushing occurring within the 6 weeks of examination deemed to be related to the treatment were recorded.

Statistical analysis

An SPSS package (version 17.0) was used for all statistical calculations. Power analysis based on pain and function severity scores determined that to have an 80% chance to establish a difference between the treatment groups, assuming a mean (SD) group difference for initial severity scores for intramuscular and intralesional groups of 2 (1) and 4 (2), respectively, and considering an effect size of 1.26 (based on previous studies with similar aim and study population), alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.8; nine subjects were needed in each group.

The primary outcome of effectiveness of intramuscular injections was studied by subtracting baseline values from the values obtained at 6 weeks for each patient for all components including pain, function and total PRTEE score. Significance of pain, function and total score reductions from week 0 to 6 for both intralesional and intramuscular groups was assessed using paired t tests. The differences in the mean changes between treatment groups at 6-week follow-up for the outcome measures were analysed using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. A two-tail significance of <0.01 was taken as representing a statistically significant difference for the outcome measures.

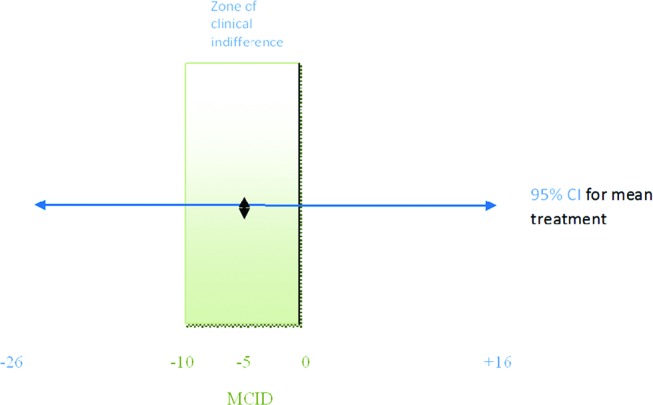

Moreover, the hypothesis of non-inferiority was checked by calculating the mean treatment difference using the PRTEE score and its 95% CI. The hypothesis is rejected if the lower limit of the 95% CI lies below the lower bound of the zone of minimal clinically important difference (MCID). The zone of clinical indifference was defined as 0±MCID. The MCID has previously been reported to be between 8 and 12 points.24 In this pilot, a value of 10 points was taken as the acceptable MCID. The PRTEE Questionnaire used to evaluate outcome was devised by Overend et al. They found it to be sensitive to change, possess high reliability (r=0.93) and moderately high validity.25 The PRTEE enables quantitative rating of pain and functional impairment associated with tennis elbow. When used as an outcome measure in trials, an MCID value is required to interpret outcomes.26 27

To test the significance of differences in the pain at the site of injection at time of injection and after 24 and 48 hours, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. A two-tail significance of <0.01 was taken as representing a statistically significant difference for the outcome measures under consideration.

Results

Primary outcome

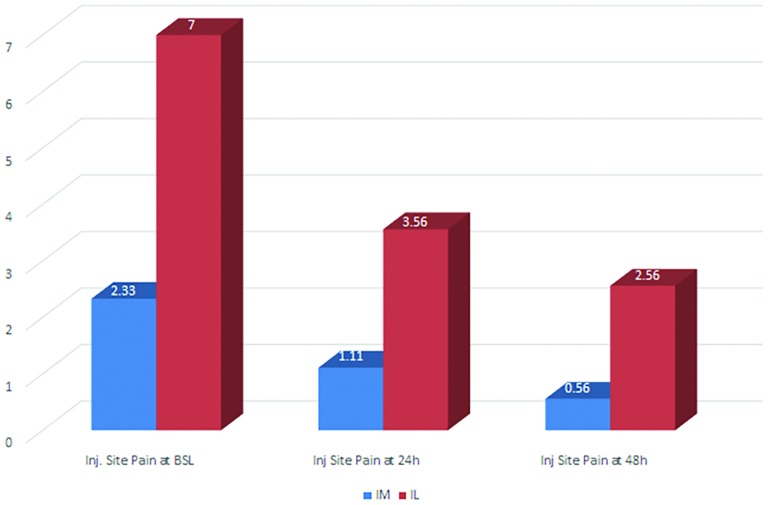

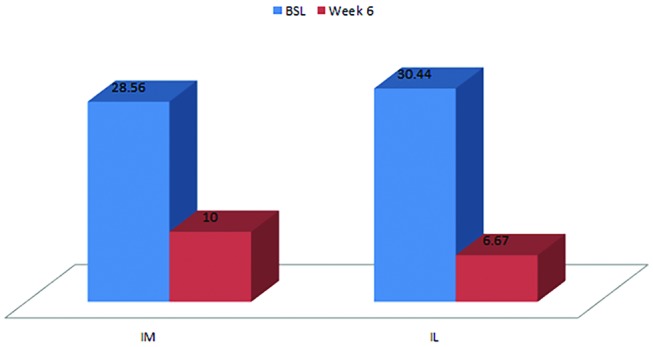

PRTEE—pain

There was a reduction in pain symptoms from baseline to the 6-week follow-up in both groups (p=0.008) (table 2). A mean improvement of 23.78 points in the intralesional group and 18.56 points in the intramuscular group was seen (figure 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for pain Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation scores in the intralesional and intramuscular groups

| Intralesional | Intramuscular | |||||

| Baseline | 6 weeks | Change | Baseline | 6 weeks | Change | |

| Mean | 30.44 | 6.67 | −23.78 | 28.56 | 10.00 | −18.56 |

| Percentile 25 | 27.50 | 1.00 | −32.00 | 20.50 | 5.00 | −28.50 |

| Percentile 75 | 33.00 | 11.00 | −18.00 | 39.00 | 15.50 | −9.00 |

| SD | 6.635 | 4.770 | 9.718 | 10.806 | 5.83 | 10.596 |

| 95% CI | 16.033 to 32.967 | 16.033 to 32.967 | ||||

| Two-tail significance | 0.008 | 0.008 | ||||

Figure 2.

Pain Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation scores in the intramuscular and intralesional groups at baseline and week 6.

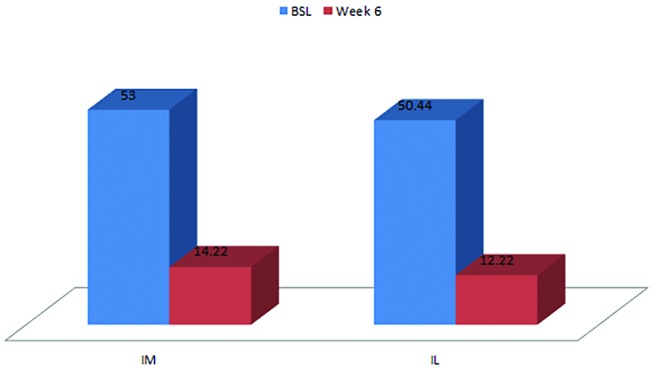

PRTEE—function

A statistically significant result (p=0.008) in favour of both intramuscular and intralesional injections was found at week 6 (figure 3) with a mean improvement of 38.22 points in the intralesional group and 38.78 points in the intramuscular group (table 3).

Figure 3.

Function Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation scores in the intramuscular and intralesinal groups at baseline and week 6.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics for function Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation scores in the intralesional and intramuscular groups

| Intralesional | Intramuscular | |||||

| Baseline | 6 weeks | Change | Baseline | 6 weeks | Change | |

| Mean | 50.44 | 12.22 | −38.22 | 53.00 | 14.22 | −38.78 |

| Percentile 25 | 33.50 | 1.50 | −55.00 | 34.50 | 6.00 | −60.50 |

| Percentile 75 | 66.50 | 21.50 | −23.00 | 72.50 | 23.50 | −15.00 |

| SD | 21.042 | 10.146 | 24.697 | 21.703 | 9.628 | 22.298 |

| 95% CI | 17.695 to 61.305 | 17.695 to 61.305 | ||||

| Two-tail significance | 0.008 | 0.008 | ||||

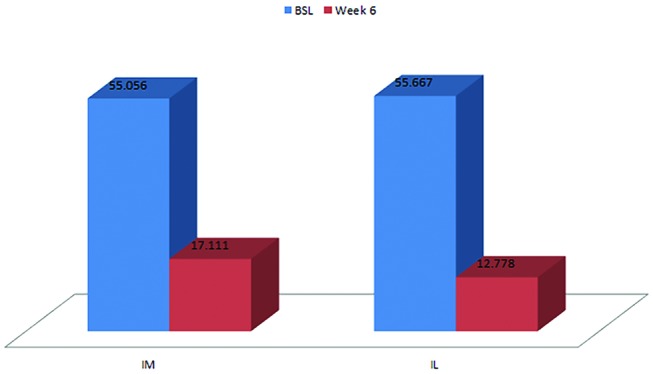

PRTEE—total

A statistically significant result (p=0.008) in favour of both intramuscular and intralesional injections was found at 6-week follow-up (figure 4). A mean improvement of 42.89 points in the intralesional group and 37.94 points in the IM group was seen (table 4).

Figure 4.

Total Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation scores in the intramuscular and intralesional groups at baseline and at week 6.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for total Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation scores in the intralesional and intramuscular groups

| Intralesional | Intramuscular | |||||

| Baseline | 6 weeks | Change | Baseline | 6 weeks | Change | |

| Mean | 55.667 | 12.778 | −42.89 | 55.056 | 17.111 | −37.94 |

| Percentile 25 | 43.500 | 1.750 | −53.00 | 37.750 | 8.500 | −58.75 |

| Percentile 75 | 65.250 | 21.250 | −29.00 | 74.750 | 28.500 | −14.75 |

| SD | 14.6245 | 9.4575 | 20.093 | 20.944 | 10.455 | 21.342 |

| 95% CI | 26.666 to 61.8334 | 26.666 to 61.8334 | ||||

| Two-tail significance | 0.008 | 0.008 | ||||

Pain at the injection site

A statistically significant result (p=0.001) in favour of intramuscular causing less pain at the injection site was noted at the time of injection (mean Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) score on 10-point Likert scale 2.33 vs 7.00) (figure 5). Statistical significance was not reached at 24 hours (p=0.031) nor at 48 hours (p=0.113) (table 5).

Figure 5.

VAS scores of injection site pain in the intramuscular and intralesional groups at baseline, 24 and 48 hours after the injection. VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of pain VAS scores at site of injection at time of injection and after 24 and 48 hours in both intralesional and intramuscular groups

|

Pain

VAS baseline |

Pain

VAS at 24 hours |

Pain

VAS at 48 hours |

||

| Intralesional | Mean | 7.00 | 3.56 | 2.56 |

| 95 % CI | 5.16 to 8.84 | 1.34 to 5.77 | 0.12 to 4.99 | |

| SD | 2.40 | 2.89 | 3.17 | |

| Intramuscular | Mean | 2.33 | 1.11 | 0.56 |

| 95 % CI | 0.45 to 4.22 | 0.00 to 2.23 | −0.22 to 1.33 | |

| SD | 2.45 | 1.45 | 1.01 | |

| Two-tail significance | 0.001 | 0.031 | 0.113 |

VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Are intramuscular injections as effective as interlesional injections in tennis elbow?

The intralesional total PRTEE mean change was 43 points (−42.89) while intramuscular total PRTEE change was 38 points (−37.94) at week 6. The difference between intralesional and intramuscular therapy was −5 points in favour of intralesional therapy. Although similar the intralesional procedure was −4.95 points better than the intramuscular procedure (table 6). This was less than the −10 points that was taken as the acceptable MCID. The 95% CI for mean treatment difference was −26 points to +16 points and since the lower limit was below the lower bound of the zone of clinical indifference (figure 6), non-inferiority could not be inferred.

Table 6.

Primary and secondary outcome for the intralesional and intramuscular arms including SD, 95% CI and effect size

|

Primary outcome

(mean change in total PRTEE score) |

Secondary outcome

(adverse events, AEs) |

SD | 95% CI | Effect size | |

| Intralesional | −42.89 | No AE | 20.09 | 1.26 | |

| Intramuscular | −37.94 | No AE | 21.34 | ||

| Difference between intralesional and intramuscular (equal variance assumed) |

−4.944 |

−4.944 |

|

−11.247 to 29.293 |

PRTEE, Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation.

Figure 6.

Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) to interpet Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation scores and 95% CI assesing whether intramuscular injections are as effective as intralesional injections in lateral epycondylopathy.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events

There were no adverse events in either group (table 6).

Discussion

The two available injection techniques were compared for the first time in this pilot study, and primary outcomes comparing effectiveness indicate that 6 weeks after an intramuscular and an intralesional steroid injection, pain, function and total PRTEE scores improve in patients suffering from lateral epicondylopathy. The intramuscular route caused less pain at the injection site at the time and up to 48 hours later. The secondary objective of monitoring adverse events revealed that both treatments are safe.

The natural course of the condition is benign and self-limiting meaning that improvement with or without treatment is seen in 70%–80% of patients within 12 months.28 While there is wide consensus on this fact, a year is a long time for patients to wait as pain and disability affects their quality of life and accounts for lost economic productivity. A safe, minimally invasive procedure could enable a faster return to their daily activities.

There are multiple modalities for treatment, conservative and operative, with varying success. Fortunately, most patients report symptomatic improvement within 1 year. Failure is associated with long duration of symptoms, high baseline pain levels at presentation, manual labour, poor coping mechanisms, involvement of the dominant arm, low socioeconomic status and concomitant pain in the neck or shoulder.29

The use of corticosteroid injections among other injection therapies for tennis elbow30 is more common due to accessibility and cost-effectiveness. Outcomes seem to vary with length of follow-up. Systematic reviews of the literature conclude that corticosteroid injections for tennis elbow may result in short-term improvements only. Smidt et al reviewed 13 randomized clinical trials (RCT) that evaluated the effects of corticosteroid injections compared with placebo, injection with local anaesthetic and other conservative treatments. The evidence showed superior short-term pain relief (6 weeks) after corticosteroid injections but no conclusive benefit after that.

Tonks et al 31 designed a study with four treatment arms: observation only, single injection, physiotherapy and single injection plus physiotherapy. Only patients allocated to the injection group had significantly improved in all parameters at 7 weeks.

Studies by Smidt et al 6 and Bisset et al 32 showed early success with corticosteroid treatment in reduction of pain and grip strength. These benefits did not persist and there was a high recurrence rate in the injection group. Coombes et al. reviewed 41 RCTs to assess efficacy and safety of corticosteroids and other injections in lateral epicondylopathy. They concluded that while corticosteroids were superior to other treatment methods in the short-term non-steroidal injections are of more benefit in the long term.

According to Poltawki and Watson24 who gathered data from 57 participants, with PRTEE scores of 13–81/10030 clinical significance was defined as ‘a little better’ if MCID for the total PRTEE score was 7/100 or 22% of baseline score. For clinical significance defined as ‘much better' or ’completely recovered’, the MCID was 11/100 or 37% of baseline score. The MCID value was higher for a subgroup with greater baseline severity. As such those with milder symptoms require considerably smaller PRTEE score changes than those with more severe presentations in order to consider that significant improvements have occurred.

VAS score (ie, Likert scale) was used to evaluate some of the outcome measures. It is known to be a reliable instrument for scoring differences in pain over time. Of note is that less pain often leads to increased activity provoking recurrent pain which should be considered when assessing the results and may explain why a more significant change was not seen.

Different injection techniques have previously been tested for tendinopathies but no studies have yet evaluated the efficacy of the intramuscular route for the treatment of lateral epicondylopathy. Easy administration, no formal training and effectiveness are all advantages that suggest the use of intramuscular corticosteroids in primary care and musculoskeletal (MSK) interface clinics. We found that an intramuscular corticosteroid injection significantly improved pain, function and total PRTEE scores at week 6. Moreover, the intramuscular route was associated with less pain than the intralesional at the site of injection at baseline.

The hypothesis of the intramuscular procedure being as effective as the intralesional intervention in lateral epicondylopathy was not supported by this study. Our population of patients was small. The power calculation was adequate only to establish an improvement in PRTEE for each group but not to establish non-inferiority with an MCID of 10. The sample size required to bring the lower limit of the 95% CI above −10 (MCID) using the estimates obtained from the data for the differences between the means (−4.9) and the pooled SD (20.73) from our study suggests that the number required may be as high as 130 in each group.

A weakness in the design of the study is a lack of placebo arms. This would have been useful to confirm response with each injection method and to enable blinding. The study could have also been extended to long-term follow-up at 6 and 12 months. A further weakness in design was that a single physician gave the injections and as such, a bias may have existed. It is believed that intralesional injections administered under US guidance offer better targeting and we did not evaluate this aspect. Other potential limitations were lack of any mechanism to confirm that patients were presented with the eccentric exercise, with wearing the tennis elbow clasp and having a formal ergonomics assessment.

It could have been beneficial to use a higher dose (120 mg) of Depo-Medrone in the intramuscular arm. In the authors experience 80 mg of intramuscular Depo-Medrone is not always effective. It is possible that body mass index may influence the response to the same dose of systemic corticosteroids and this was not determined.

The pathophysiology of the disease and the pathomorphology of the affected connective tissue in lateral epicondylopathy is not well defined. The existing data outline a spectrum of changes from early inflammation to necrosis.1–4 27 With this in mind, success of treatment likely correlates with the duration of disease in addition to treatment modality. Steroids will most likely work earlier, when inflammation is the characteristic pathological finding in contrast to degeneration/necrosis later in the course of the disease. As symptom duration was not recorded in this study, we cannot exclude the possibility that a predefined cohort with early disease, less than 3 months duration, responds better.

Conclusion

It is well established that steroid injections for tennis elbow result in short-term benefits.

This study further confirms that both intralesional and intramuscular injections are effective and safe. Intramuscular injections were better tolerated as they were less painful than intralesional injections at the site of injection at the time of administration. We did not confirm non-inferiority of the intramuscular over the intralesional procedure. The response and the findings provided by the study however could represent the grounds for a larger study focusing on the role of intramuscular injections in tennis elbow.

Confirmation of these findings in a larger study will offer management options in primary care as specialist training is not required to perform intramuscular injections. Such treatment could be undertaken by healthcare professionals such as practice nurses and physiotherapists with minimal training offering treatment to enable early return to daily activities and work.

References

- 1. Nirschl RP, Ashman ES. Tennis elbow tendinosis (epicondylitis). Instr Course Lect 2004;53:587–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nirschl RP. Elbow tendinosis/tennis elbow. Clin Sports Med 1992;11:851–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kurppa K, Waris P, Rokkanen P. Tennis elbow. lateral elbow pain syndrome. Scand J Work Environ Health 1979;5 suppl 3:15–18 . 10.5271/sjweh.2676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Per AFH Renström. Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science, Tennis. Wiley-Blackwell publishing company, 2002:1–330. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tennis Elbow-CAP. The Lancet 1886;128:1083. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)49587-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smidt N, Assendelft WJ, van der Windt DA, et al. Corticosteroid injections for lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review. Pain 2002;96:23–40. 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00388-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Faro F, Wolf JM. Lateral epicondylitis: review and current concepts. J Hand Surg Am 2007;32:1271–9. 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krogh TP, Bartels EM, Ellingsen T, et al. Comparative effectiveness of injection therapies in lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:1435–46. 10.1177/0363546512458237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2010;376:1751–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61160-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coombes BK, Bisset L, Brooks P, et al. Effect of corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, or both on clinical outcomes in patients with unilateral lateral epicondylalgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2013;309:461–9. 10.1001/jama.2013.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Torp-Pedersen TE, Torp-Pedersen ST, Qvistgaard E, et al. Effect of glucocorticosteroid injections in tennis elbow verified on colour Doppler ultrasonography: evidence of inflammation. Br J Sports Med 2008;42:978–82. 10.1136/bjsm.2007.041285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Genovese MC. Joint and soft-tissue injection. A useful adjuvant to systemic and local treatment. Postgrad Med 1998;103:125–34. 10.3810/pgm.1998.02.316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rifat SF, Moeller JL. Site-specific techniques of joint injection. useful additions to your treatment repertoire. Postgrad Med 2001;109:123–136 . 10.3810/pgm.2001.03.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lewis M, Hay EM, Paterson SM, et al. Local steroid injections for tennis elbow: does the pain get worse before it gets better? Results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain 2005;21:330–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Roberts WO. Lateral epicondylitis injection. Phys Sportsmed 2000;28:93–4. 10.3810/psm.2000.07.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smidt N, Assendelft WJ, van der Windt DA, et al. Corticosteroid injections for lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review. Pain 2002;96:23–40. 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00388-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Anastassiades T, Dziewiatkowski D. The effect of cortisone on the metabolism of connective tissues in the rat. J Lab Clin Med 1970;75:826–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ekeberg OM, Bautz-Holter E, Tveitå EK, et al. Subacromial ultrasound guided or systemic steroid injection for rotator cuff disease: randomised double blind study. BMJ 2009;338:a3112. 10.1136/bmj.a3112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bellapianta J, Swartz F, Lisella J, et al. Randomized prospective evaluation of injection techniques for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Orthopedics 2011;34:e708–12. 10.3928/01477447-20110922-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roberts WO. Lateral epicondylitis injection. Phys Sportsmed 2000;28:93–4. 10.3810/psm.2000.07.1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Overend TJ, Wuori-Fearn JL, Kramer JF, et al. Reliability of a patient-rated forearm evaluation questionnaire for patients with lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Ther 1999;12:31–7. 10.1016/S0894-1130(99)80031-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Newcomer KL, Martinez-Silvestrini JA, Schaefer MP, et al. Sensitivity of the Patient-rated forearm evaluation questionnaire in lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Ther 2005;18:400–6. 10.1197/j.jht.2005.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stratford P, Levy DR, Gauldie S, et al. Extensor carpi radialis tendonitis: a validation of selected outcome measures. Physiotherapy Canada 1987;39:250–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poltawski L, Watson T. Measuring clinically important change with the Patient-rated tennis elbow evaluation. Hand Therapy 2011;16:52–57. 10.1258/ht.2011.011013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Overend TJ, Wuori-Fearn JL, Kramer JF, et al. Reliability of a patient-rated forearm evaluation questionnaire for patients with lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Ther 1999;12:31–7. 10.1016/S0894-1130(99)80031-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nilsson P, Baigi A, Marklund B, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and determination of the reliability and validity of PRTEE-S (Patientskattad Utvärdering av Tennisarmbåge), a questionnaire for patients with lateral epicondylalgia, in a Swedish population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:79. 10.1186/1471-2474-9-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leung HB, Yen CH, Tse PY. Reliability of hong kong chinese version of the Patient-rated Forearm Evaluation Questionnaire for lateral epicondylitis. Hong Kong Med J 2004;10:172–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boyer MI, Hastings H. Lateral tennis elbow: "Is there any science out there?". J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999;8:481–91. 10.1016/S1058-2746(99)90081-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haahr JP, Andersen JH. Prognostic factors in lateral epicondylitis: a randomized trial with one-year follow-up in 266 new cases treated with minimal occupational intervention or the usual approach in general practice. Rheumatology 2003;42:1216–25. 10.1093/rheumatology/keg360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rabago D, Best TM, Zgierska AE, et al. A systematic review of four injection therapies for lateral epicondylosis: prolotherapy, polidocanol, whole blood and platelet-rich plasma. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:471–81. 10.1136/bjsm.2008.052761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tonks JH, Pai SK, Murali SR. Steroid injection therapy is the best conservative treatment for lateral epicondylitis: a prospective randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2006;61:240–6. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bisset L, Beller E, Jull G, et al. Mobilisation with movement and exercise, corticosteroid injection, or wait and see for tennis elbow: randomised trial. BMJ 2006;333:939. 10.1136/bmj.38961.584653.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]