Abstract

Aim

To assess the effects of a functional and individualised exercise programme on gait biomechanics during walking in people with knee OA.

Methods

Sixty participants were randomised to 12 weeks of facility-based functional and individualised neuromuscular exercise therapy (ET), 3 sessions per week supervised by trained physical therapists, or a no attention control group (CG). Three-dimensional gait analyses were used, from which a comprehensive list of conventional gait variables were extracted (totally 52 kinematic, kinetic and spatiotemporal variables). According to the protocol, the analyses were based on the ‘Per-Protocol’ population (defined as participants following the protocol with complete and valid gait analyses). Analysis of covariance adjusting for the level at baseline was used to determine differences between groups (95% CIs) in the changes from baseline at follow-up.

Results

The per-protocol population included 46 participants (24 ET/22 CG). There were no group differences in the analysed gait variables, except for a significant group difference in the second peak knee flexor moment and second peak vertical ground reaction force.

Conclusion

While plausible we have limited confidence in the findings due to multiple statistical tests and lack of biomechanical logics. Therefore we conclude that a 12-week supervised individualised neuromuscular exercise programme has no effects on gait biomechanics. Future studies should focus on exercise programmes specifically designed to alter gait patterns, or include other measures of mobility, such as walking on stairs or inclined surfaces.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01545258.

Keywords: Knee osteoarthritis, Exercise therapy, gait analysis, randomized controlled trial.

What are the new findings?

A 12-week functional exercise programme does not alter the walking biomechanics in patients with knee osteoarthritis.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the near future?

The biomechanical rationale for delivering this kind of exercise programme is weak, and should not be used to inform clinical decisions with the patients.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is a chronic disease associated with significant mobility limitations including impaired walking ability. Because walking is the most natural and convenient way of ambulation, limitations in walking ability is a major source of restrictions in an individual’s independency and participation in everyday life.

While patient-reported physical functioning is included in the core set of outcome measures,1 detailed evaluation of walking performance following treatments in knee OA is seldom reported. Gait analysis provides objective and quantitative data on the walking biomechanics, reflecting the biomechanical function of the single joints, and of the gait pattern as a whole.

Knee OA cannot be cured wherefore its management is an enormous challenge for clinicians and society. The ultimate treatment for knee OA is surgical joint replacement but conservative treatments are recommended before surgery.2 One recommended conservative non-pharmacological treatment for OA is exercise.3 A fundamental aim of exercise therapy is to improve mobility in relation to activities of daily living, such as walking. Comprehensive analyses of how exercise affects walking biomechanics in knee OA could inform strategies to exercise optimisation.

The effects of exercise on walking biomechanics have been assessed in a number of studies.4–8 The focus has been on strengthening exercises, and the biomechanical outcomes have focused on knee adduction moment (KAM), but have not shown any effects of exercise on these outcomes. While the KAM during walking has been a specific focus in relation to knee OA, more comprehensive analyses of the effects of exercise on the walking biomechanics of the entire lower extremity has not been investigated before. One study compared strengthening exercises with individualised functional exercises in people with arthritis and lower extremity impairments and found beneficial effects of functional and individualised exercises compared with strengthening exercises on walking speed and mechanical work at the ankle, knee and hip joints.9 In contrast, a recent study compared similar functional exercises with quadriceps strengthening, and found no group differences in KAM, KAM angular impulses, knee flexor moments or walking speed, but did not report on other lower extremity gait analysis outcomes.6 Thus, it remains ambiguous if functional and individualised exercise affects lower extremity gait biomechanics.

Therefore, the objective of this exploratory outcome analysis of a randomised study is to assess the effects of a functional and individualised therapeutic exercise programme on lower extremity gait biomechanics in people with knee OA.

Methods

This is the report of exploratory outcome analyses of a randomised controlled study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01545258). The primary outcome is reported elsewhere.10

Participants were recruited through March–December 2012 from the OA outpatient clinic of Copenhagen University Hospital at Frederiksberg, Copenhagen, Denmark. Eligible participants were adults aged 40 years or over with a clinical diagnosis of knee OA confirmed by radiography, and a body mass index between 20 kg/m2 and 35 kg/m2. The exclusion criteria included (but were not restricted to) participation in exercise therapy within the previous 3 months, inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, and lower extremity joint replacement. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to one of two groups stratified by gender; an exercise therapy group (ET) receiving exercise therapy for 12 weeks, or a control group (CG) receiving no attention for 12 weeks.

At inclusion, the participants’ most symptomatic knee was deemed target of all subsequent assessments and measurements. All patients gave written informed consent and the study was approved by the local research ethics committee and performed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Intervention

The patients assigned to the ET were offered facility-based exercise therapy supervised by a trained physiotherapist three times weekly for 12 weeks. The exercise was group-based and the participants consecutively joined the group as they were included. The exercise programme lasted approximately 1 hour and consisted of a warm-up phase (bicycle ergometer at moderate intensity) followed by a circuit training programme focusing on strength and coordination exercises of the trunk, hips and knees. The exercises were performed with free weights, elastic rubber bands or body weight as resistance. Progression was made on an individual basis, according to a prespecified progression protocol.

The participants assigned to the CG received no attention during the 12 weeks.

Gait analysis

Kinematic data were acquired using a six-camera three-dimensional motion analysis system (MX-F20, Vicon, Oxford, UK) operating at 100 Hz synchronised with two force platforms (AMTI OR 6-5-1000, AMTI, USA) embedded in the laboratory floor (1500 Hz). Three-dimensional orientations of 7 body segments of interest (pelvis, thighs, shanks, feet) were obtained by tracking trajectories of markers placed according to a common commercially available kinematic model (Plug-In-Gait, Vicon, Oxford, UK). Markers were placed directly on the skin and patients wore their own comfortable shoes during all trials.

Participants walked a 10 m walkway freely until a stable and comfortable walking speed was obtained. A photocell system registered the walking speed with a digital display providing the subjects with immediate visual feedback. The starting point was adjusted for each subject to ensure a clean foot strike on either of the two force platforms. Once walking speed and starting points were determined, a series consisting of 10 acceptable trials (within ±0.1 km/h of target speed) were recorded.

The analyses focused on one gait cycle (one platform heel strike to the next) and gait variables were calculated using the Plug-In-Gait model (Vicon, Oxford, UK). We extracted a comprehensive list of conventional variables related to hip, knee and ankle kinematics (joint angles), kinetics (joint moments and work) and spatiotemporal variables (table 1). All trials were analysed individually and subsequently each variable was averaged across the 10 accepted trials for each participant.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Control group | Exercise group | ||

| Randomised (n=29) |

Per protocol (n=22) |

Randomised (n=31) |

Per protocol (n=24) |

|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age, years | 61.3 (7.1) | 61.4 (7.2) | 65.9 (8.5) | 64.9 (9.1) |

| Female sex, no. (%) | 21 (72%) | 16 (73%) | 27 (87%) | 22 (92%) |

| Height, m | 1.72 (0.09) | 1.71 (0.09) | 1.69 (0.08) | 1.69 (0.08) |

| Weight, kg | 83.3 (15.0) | 83.6 (15.7) | 81.9 (14.1) | 83.1 (14.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.1 (4.5) | 28.4 (4.6) | 28.7 (4.2) | 29.1 (4.1) |

| Pain, 0–100 mm | 63.3 (12.4) | 62.9 (11.0) | 56.5 (14.8) | 56.8 (16.1) |

| Gait analysis | (n=28)* | (n=30)* | ||

| Hip kinematics (stance and swing) | ||||

| Max. flexion angle, degrees | 40.6 (9.1) | 38.7 (9.3) | 39.7 (5.8) | 40.2 (6.2) |

| Max. extension angle, degrees | −8.3 (9.1) | −9.8 (9.0) | −8.8 (7.9) | −7.5 (7.8) |

| Max. adduction angle, degrees | −11.2 (5.2) | −10.6 (4.4) | −11.6 (3.8) | −12.0 (3.7) |

| Max. abduction angle, degrees | 4.0 (4.2) | 4.3 (3.9) | 3.9 (5.0) | 3.1 (4.8) |

| Max. external rotation angle, degrees | 16.6 (10.2) | 15.6 (10.3) | 13.8 (14.7) | 12.6 (14.8) |

| Max. internal rotation angle, degrees | −14.9 (14.4) | −15.0 (13.5) | −13.5 (14.9) | −12.1 (16.2) |

| Hip kinetics (stance only; net internal moments) | ||||

| Peak extensor moment, Nm/kg | 1.09 (0.32) | 1.03 (0.29) | 1.03 (0.27) | 1.00 (0.25) |

| Peak flexor moment, Nm/kg | −1.00 (0.25) | −0.99 (0.26) | −1.08 (0.26) | −1.05 (0.27) |

| First peak abductor moment, Nm/kg | 0.90 (0.15) | 0.89 (0.14) | 0.90 (0.20) | 0.86 (0.15) |

| Second peak adductor moment, Nm/kg | 0.65 (0.14) | 0.67 (0.14) | 0.64 (0.14) | 0.62 (0.10) |

| First peak lateral rotation moment, Nm/kg | −0.13 (0.04) | −0.14 (0.04) | −0.13 (0.05) | 0.86 (0.15) |

| Second peak medial rotation moment, Nm/kg | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.62 (0.10) |

| First peak resultant moment, Nm/kg | 1.20 (0.26) | 1.15 (0.24) | 1.14 (0.24) | 1.09 (0.19) |

| Second peak resultant moment, Nm/kg | 1.15 (0.23) | 1.15 (0.23) | 1.22 (0.27) | 1.18 (0.26) |

| Positive work, Joule | 0.23 (0.07) | 0.22 (0.08) | 0.23 (0.08) | 0.21 (0.07) |

| Negative work, Joule | −0.20 (0.12) | −0.19 (0.12) | −0.22 (0.11) | −0.20 (0.12) |

| Knee kinematics (stance and swing) | ||||

| Angle at heel strike, degrees | 13.5 (6.8) | 12.2 (5.7) | 13.9 (5.7) | 13.8 (5.9) |

| First peak flexion angle, degrees | 23.7 (6.2) | 23.1 (6.2) | 25.7 (6.9) | 25.8 (7.6) |

| Mid-stance peak extension angle, degrees | 7.0 (6.9) | 6.2 (6.3) | 9.6 (6.9) | 10.1 (7.0) |

| Peak swing phase flexion angle, degrees | 59.6 (8.5) | 59.5 (8.9) | 61.4 (8.5) | 61.4 (9.4) |

| Knee kinetics (stance only; net internal moments) | ||||

| First peak flexor moment, Nm/kg | −0.40 (0.13) | −0.39 (0.10) | −0.40 (0.14) | −0.40 (0.13) |

| First peak extensor moment, Nm/kg | 0.82 (0.26) | 0.80 (0.25) | 0.88 (0.36) | 0.65 (0.22) |

| Second peak flexor moment, Nm/kg | −0.11 (0.18) | −0.14 (0.16) | −0.05 (0.19) | −0.03 (0.16) |

| First peak abductor moment, Nm/kg | 0.69 (0.24) | 0.67 (0.25) | 0.66 (0.22) | 0.65 (0.22) |

| Second peak abductor moment, Nm/kg | 0.49 (0.21) | 0.50 (0.23) | 0.45 (0.18) | 0.44 (0.18) |

| Abductor angular impulse, Nm*s/kg | 24.8 (10.7) | 24.7 (11.4) | 23.0 (9.0) | 23.2 (9.4) |

| First peak medial rotation moment, Nm/kg | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.05) |

| Second peak lateral rotation moment, Nm/kg | −0.08 (0.05) | −0.09 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.04) |

| First peak resultant moment, Nm/kg | 1.07 (0.27) | 1.04 (0.26) | 1.12 (0.26) | 1.11 (0.29) |

| Second peak resultant moment, Nm/kg | 0.58 (0.16) | 0.58 (0.17) | 0.57 (0.12) | 0.56 (0.12) |

| Positive work, Joule | 0.24 (0.12) | 0.23 (0.10) | 0.27 (0.15) | 0.26 (0.17) |

| Negative work, Joule | −0.28 (0.09) | −0.26 (0.08) | −0.29 (0.09) | −0.29 (0.10) |

| Ankle kinematics (stance and swing) | ||||

| Max. plantarflexion (early stance), degrees | 2.1 (4.9) | 1.6 (5.1) | 2.2 (3.9) | 2.2 (4.0) |

| Max. dorsiflexion (late stance), degrees | 18.3 (4.7) | 17.7 (3.9) | 20.4 (5.9) | 20.9 (6.4) |

| Swing dorsiflexion angle, degrees | 7.6 (8.1) | 7.1 (8.3) | 9.8 (7.6) | 9.4 (8.3) |

| Ankle kinetics (stance only; net internal moments) | ||||

| Peak dorsiflexor moment (early stance), Nm/kg | −0.24 (0.10) | −0.25 (0.11) | −0.20 (0.12) | −0.19 (0.13) |

| Peak plantarflexor moment (late stance), Nm/kg | 1.42 (0.18) | 1.41 (0.18) | 1.47 (0.22) | 1.45 (0.21) |

| Peak resultant moment (late stance), Nm/kg | 1.43 (0.18) | 1.41 (0.18) | 1.48 (0.22) | 1.46 (0.21) |

| Positive work, Joule | 0.34 (0.06) | 0.34 (0.06) | 0.34 (0.09) | 0.33 (0.08) |

| Negative work, Joule | −0.19 (0.07) | −0.18 (0.06) | −0.21 (0.06) | −0.21 (0.07) |

| Spatiotemporal variables | ||||

| Walking speed, m/s | 1.37 (0.17) | 1.36 (0.14) | 1.37 (0.25) | 1.35 (0.27) |

| Step length, m | 0.72 (0.07) | 0.71 (0.05) | 0.72 (0.1) | 0.71 (0.11) |

| Cadence, steps/min | 116.8 (10.2) | 116.4 (10.4) | 116.9 (9.4) | 116.5 (10.3) |

| Double support, % | 0.26 (0.05) | 0.25 (0.05) | 0.26 (0.09) | 0.26 (0.10) |

| Single support, % | 0.39 (0.05) | 0.39 (0.05) | 0.39 (0.05) | 0.39 (0.05) |

| Foot progression angle, degrees | 4.0 (6.1) | 4.1 (4.8) | 5.3 (5.0) | 5.8 (5.4) |

| Ground reaction forces and support moment (stance only) | ||||

| First peak vertical ground reaction force, N | 113.7 (9.5) | 112.4 (9.3) | 116.9 (12.1) | 116.1 (13.0) |

| Second peak vertical ground reaction force, N | 106.5 (7.7) | 106.9 (7.6) | 108.1 (9.1) | 106.7 (8.2) |

| First peak a-p ground reaction force, N | 20.8 (4.0) | 20.5 (3.4) | 21.1 (6.1) | 20.6 (6.6) |

| Second peak a-p ground reaction force, N | −20.9 (3.5) | −21.0 (3.3) | −20.9 (5.9) | −20.5 (6.1) |

| First peak support moment, Nm/kg | 1.34 (0.40) | 1.30 (0.42) | 1.34 (0.39) | 1.34 (0.43) |

| Second peak support moment, Nm/kg | 0.69 (0.25) | 0.69 (0.28) | 0.70 (0.31) | 0.68 (0.32) |

*One invalid gait analysis at baseline (see figure flow diagram)

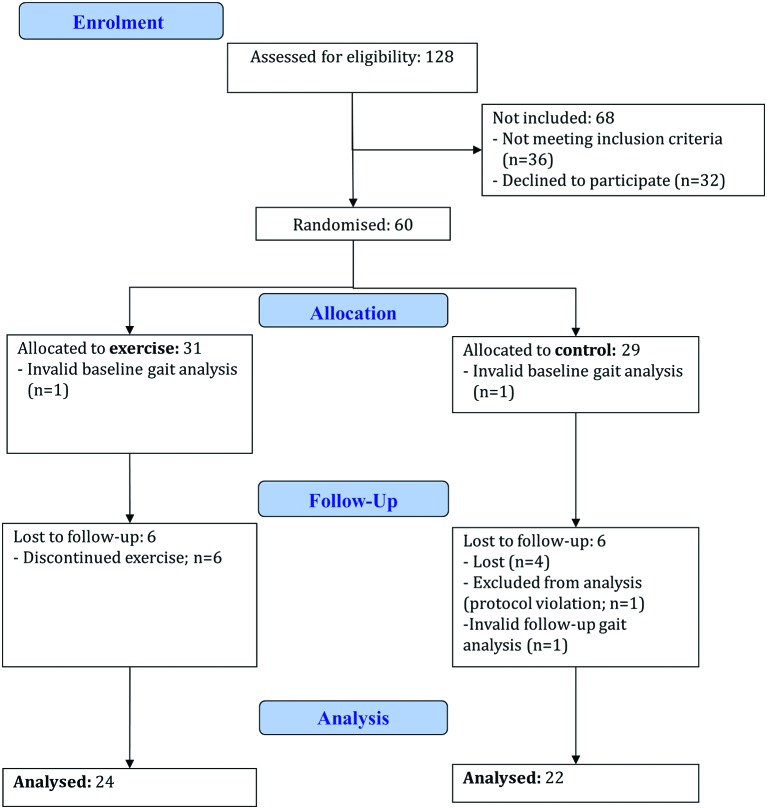

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study participants.

Sample size

The sample size was based on the primary outcome,10 and accounting for possible dropouts the sample was 60 participants.

Randomisation

For allocation of the patients, a computer-generated list of random numbers is used. Randomisation sequence was stratified by gender with a 1:1 allocation using random block sizes of 2, 4 and 6. The allocation sequence was concealed from the researchers enrolling and assessing participants in sequentially numbered, opaque and sealed envelopes. To prevent subversion of the allocation sequence, the name and date of birth of the participant were written on the envelope. Allocation occurred only after a participant completed all baseline assessments. Whereas the participating patients were aware of their group allocation, outcome assessors and data analysts were kept blinded to the allocation.

Statistical analyses

As this study aims at exploring the mechanistic effects of exercise on gait biomechanics, the analyses were based on the ‘per protocol' population, defined as those participants that had followed the study protocol (attendance to at least 24 exercise sessions in the ET; no exercise in the CG) and with complete data sets at baseline and follow-up. The analyses focused on group mean differences in changes from baseline in gait variables, calculated as the baseline value subtracted from the follow-up value. General linear models were used with a factor for group and adjusting for the baseline value. All analyses were done using SAS software (v 9.2), and statistical significance was accepted at p <0.05. Because this study did not work under any prespecified hypotheses, no adjustments for multiple statistical tests were done.

Results

Of the 60 included participants, 31 were randomised to ET and 29 to CG. Baseline characteristics and gait variables are presented in table 1.

The analyses involved participants who adhered to the protocol, and had complete data recordings. In the ET group, six participants were lost to follow-up and one had invalid baseline gait analysis. The remaining 24 participants all adhered to the protocol (ie, attendance to at least 24 sessions) and defined the per-protocol population in the ET group.

In the CG one participant had invalid gait analysis at baseline and one at follow-up, four were lost to follow-up, and there was one protocol violation; a man in the control group disclosed participation in exercise outside the study. The remaining 22 participants defined the per-protocol population in the CG. Thus, 46 participants constituted the per protocol population.

Except from a statistically significant group difference in the second peak knee flexor moment and second peak vertical ground reaction force, there were no group differences in the analysed gait variables as presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Change from baseline in gait variables

| Variable Change from baseline |

Control group (n=22) | Exercise group (n=24) | Group difference | |

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Hip kinematics (stance and swing) | ||||

| Max. flexion angle, degrees | −0.5 (−3.4 to 2.4) | −1.7 (−4.4 to 1.1) | 1.2 (−2.8 to 5.1) | 0.56 |

| Max. extension angle, degrees | −1.6 (−5.0 to 1.8) | −0.6 (−3.9 to 2.6) | −0.9 (−5.6 to 3.8) | 0.69 |

| Max. adduction angle, degrees | −0.1 (−2.1 to 1.9) | 0.1 (−1.7 to 2.0) | −0.2 (−3.0 to 2.5) | 0.86 |

| Max. abduction angle, degrees | −0.2 (−1.7 to 1.3) | −0.4 (−1.9 to 1.0) | 0.2 (−1.9 to 2.3) | 0.84 |

| Max. external rotation angle, degrees | −2.7 (−8.2 to 2.7) | −0.1 (−5.4 to 5.1) | −2.6 (−10.2 to 5.0) | 0.50 |

| Max. internal rotation angle, degrees | −3.1 (−9.0 to 2.8) | −0.8 (−6.4 to 4.9) | −2.4 (−10.5 to 5.8) | 0.56 |

| Hip kinetics (stance only; net internal moments) | ||||

| Peak extensor moment, Nm/kg | −0.03 (−0.16 to 0.09) | −0.00 (−0.12 to 0.12) | −0.03 (−0.21 to 0.14) | 0.72 |

| Peak flexor moment, Nm/kg | −0.05 (−0.16 to 0.07) | −0.04 (−0.15 to 0.06) | −0.00 (−0.16 to 0.16) | 0.99 |

| First peak abductor moment, Nm/kg | −0.00 (−0.09 to 0.09) | 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.10) | −0.02 (−0.14 to 0.11) | 0.81 |

| Second peak adductor moment, Nm/kg | −0.05 (−0.12 to 0.02) | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.10) | −0.09 (−0.18 to 0.01) | 0.07 |

| First peak lateral rotation moment, Nm/kg | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.01) | −0.00 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.88 |

| Second peak medial rotation moment, Nm/kg | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.01) | 0.02 (−0.00 to 0.04) | −0.03 (−0.05 to 0.00) | 0.09 |

| First peak resultant moment, Nm/kg | −0.01 (−0.12 to 0.10) | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.08) | 0.01 (−0.14 to 0.17) | 0.86 |

| Second peak resultant moment, Nm/kg | 0.02 (−0.11 to 0.14) | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.16) | −0.03 (−0.20 to 0.15) | 0.77 |

| Positive work (stance), Joule | −0.01 (−0.05 to 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.03 to 0.04) | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | 0.50 |

| Negative work (stance), Joule | −0.04 (−0.10 to 0.01) | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.03) | −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.05) | 0.45 |

| Knee kinematics (stance and swing) | ||||

| Angle at heel strike, degrees | 1.3 (−1.3 to 3.9) | −0.2 (−2.8 to 2.3) | 1.5 (2.1 to 5.2) | 0.41 |

| First flexion angle (early stance), degrees | 1.7 (−0.8 to 4.2) | −1.2 (−3.6 to 1.3) | 2.9 (−0.7 to 6.4) | 0.11 |

| Mid-stance extension angle, degrees | 1.1 (−1.6 to 3.7) | −1.3 (−3.8 to 1.3) | 2.3 (−1.4 to 6.1) | 0.22 |

| Swing phase flexion angle, degrees | −0.6 (−3.8 to 2.7) | −1.1 (−4.2 to 2.1) | 0.5 (−4.0 to 5.1) | 0.81 |

| Knee kinetics (stance only; net internal moments) | ||||

| First peak extensor moment (early stance), Nm/kg | 0.04 (−0.10 to 0.18) | −0.01 (−0.15 to 0.12) | 0.05 (−0.14 to 0.25) | 0.59 |

| Second peak flexor moment (late stance), Nm/kg | 0.05 (−0.02 to 0.11) | −0.5 (−0.11 to 0.01) | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.19) | 0.04 |

| First peak abductor moment, Nm/kg | 0.05 (−0.03 to 0.12) | 0.06 (−0.01 to 0.13) | −0.01 (−0.11 to 0.09) | 0.84 |

| Second peak abductor moment, Nm/kg | 0.07 (0.01 to 0.014) | 0.09 (0.02 to 0.16) | −0.02 (−0.12 to 0.08) | 0.72 |

| Abductor angular impulse, Nm×s/kg | 2.91 (−0.60 to 6.41) | 3.09 (−0.27 to 6.45) | −0.18 (−5.04 to 4.58) | 0.94 |

| First peak medial rotation moment, Nm/kg | 0.004 (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.025 (0.004 to 0.05) | −0.02 (−0.05 to 0.01) | 0.17 |

| Second peak lateral rotation moment, Nm/kg | −0.02 (−0.04; −0.00) | −0.013 (−0.03 to 0.01) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 0.48 |

| First peak resultant moment, Nm/kg | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.15) | 0.04 (-0.06 to 0.14) | 0.01 (−0.14 to 0.15) | 0.91 |

| Second peak resultant moment, Nm/kg | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.10) | 0.06 (0.01 to 0.11) | −0.02 (−0.10 to 0.06) | 0.59 |

| Positive work (stance), Joule | 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.07) | 0.02 (-0.04 to 0.08) | −0.01 (−0.09 to 0.08) | 0.84 |

| Negative work (stance), Joule | 0.003 (−0.04 to 0.05) | −0.01 (-0.05 to 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.05 to 0.08) | 0.69 |

| Ankle kinematics (stance and swing) | ||||

| Max. plantarflexion (early stance), degrees | −0.5 (−2.3 to 1.3) | −1.6 (−3.3 to 0.2) | 1.1 (−1.4 to 3.6) | 0.38 |

| Max. dorsiflexion (late stance), degrees | −0.1 (−1.9 to 1.7) | −1.3 (−3.0 to 0.5) | 1.1 (−1.5 to 3.7) | 0.38 |

| Swing phase dorsiflexion angle, degrees | 2.3 (−0.5 to 5.0) | −0.4 (−3.0 to 2.2) | 2.7 (−1.2 to 6.5) | 0.17 |

| Ankle kinetics (stance only; net internal moments) | ||||

| Peak dorsiflexor moment (early stance), Nm/kg | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.07) | −0.00 (−0.05 to 0.05) | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.10) | 0.48 |

| Peak plantarflexor moment (late stance), Nm/kg | −0.07 (−0.18 to 0.04) | −0.00 (−0.11 to 0.10) | −0.07 (−0.22 to 0.08) | 0.37 |

| Peak resultant moment (late stance), Nm/kg | −0.07 (−0.19 to 0.04) | −0.00 (-0.11 to 0.10) | −0.07 (−0.23 to 0.083) | 0.36 |

| Positive work (stance), Joule | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.03) | 0.00 (-0.03 to 0.04) | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.04) | 0.67 |

| Negative work (stance), Joule | 0.00 (−0.03 to 0.04) | −0.01 (-0.04 to 0.02) | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.06) | 0.46 |

| Spatiotemporal variables | ||||

| Walking speed, m/s | −0.05 (−0.14 to 0.04) | −0.03 (−0.12 to 0.06) | −0.02 (−0.15 to 0.11) | 0.79 |

| Step length, m | −0.02 (−0.07 to 0.02) | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.03) | −0.01 (−0.07 to 0.05) | 0.74 |

| Cadence, steps/min | −2.9 (−7.1 to 1.4) | −1.8 (−5.8 to 2.3) | −1.1 (−6.9 to 4.8) | 0.71 |

| Double support, % | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.05) | −0.00 (−0.03 to 0.03) | 0.02 (−0.03 to 0.06) | 0.45 |

| Single support, % | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.03) | 0.01 (−0.00 to 0.03) | −0.00 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.74 |

| Foot progression angle, degrees | 1.0 (−1.4 to 3.4) | −1.4 (−3.7 to 0.9) | 2.4 (−0.9 to 5.7) | 0.15 |

| Ground reaction forces and support moment (stance only) | ||||

| First peak vertical ground reaction force, N | −1.5 (−6.6 to 3.7) | 1.0 (−4.0 to 5.9) | −2.4 (−9.7 to 4.7) | 0.50 |

| Second peak vertical ground reaction force, N | −2.7 (−5.9 to 0.6) | 2.3 (−0.9 to 5.4) | −4.9 (−9.5:−0.4) | 0.03 |

| First peak a-p ground reaction force, N | −0.9 (−3.4 to 1.5) | −0.0 (−2.4 to 2.3) | −0.9 (−4.3 to 2.4) | 0.59 |

| Second peak a-p ground reaction force, N | 1.2 (−1.0 to 3.5) | 0.8 (−1.4 to 2.9) | 0.4 (−2.6 to 3.5) | 0.77 |

| First peak support moment, Nm/kg | −0.03 (−0.25 to 0.20) | 0.04 (−0.18 to 0.25) | −0.06 (−0.4 to 0.2) | 0.68 |

| Second peak support moment, Nm/kg | 0.02 (−0.13 to 0.17) | 0.09 (−0.05 to 0.23) | −0.07 (−0.28 to 0.13) | 0.49 |

Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the effects of functional exercises on gait biomechanics in knee OA. Overall, there were no group differences in the gait changes, except for two variables (second peak knee flexor moment and second peak vertical ground reaction force). Our confidence in these two statistically significant observations is limited, as the likelihood of these occurring by chance is not negligible due to multiple statistical tests. Also, the group difference in the change of the second peak vertical ground reaction force is very small and probably without any clinical significance. Further, while these findings may be plausible we would expect changes in other variables, such as the ankle plantarflexor moment, in the late stance phase to happen concurrently to be biomechanically meaningful.

While several previous studies have assessed the effects of exercise on gait, the studies have all focused on selected variables and on quadriceps strengthening.4–8 No studies have found effects of exercise and thus corroborate the present results. One study suggested beneficial effects of the functional exercises compared with strengthening exercises on ankle, knee and hip power,9 whereas a recent comparison of functional and strengthening exercises did not show any differences in knee joint moments.6 While we assessed both positive and negative work in ankle, knee and hip joints, we did not assess power in the same way as by McGibbon et al.9 However, our comprehensive analyses report a range of widely used gait variables, and the results do not suggest any group differences to support changes in joint powers as reported by McGibbon et al.9

Bennell et al 6 compared gait changes between functional and strengthening exercises, applying a rigorous clinical trial design and intention-to-treat analyses, yet without group differences in selected gait variables. In our study we compared functional exercises with a no attention control group, included a comprehensive evaluation of gait variables and constrained our analyses to the participants that adhered to the protocol. Thus, the chances of detecting any effects of functional exercises on gait biomechanics were maximised, yet no differences were found.

Although the functional exercise programme that we employed includes specific exercises aiming at improving walking performance, the majority of the exercises are not specifically aimed at walking biomechanics. This may explain the absence of effects in the gait biomechanics in this and previous studies.4–8 Another explanation could be that the participants in our study did not have significant gait aberrations at baseline. Thus, it is therefore not surprising that the functional exercise programme had no effects on the gait as this was not anomalous to begin with. It is possible that the exercise programme may have affected the biomechanics of other locomotor tasks, such as stair ambulation or walking on inclined or declined surfaces.

Conventional gait analysis may not necessarily reflect the mobility limitations experienced by the patients with knee OA . While walking is a basic activity of daily living, the inclusion of other measures of everyday mobility could have shown beneficial effects of exercise and would have enhanced our study. Further, our small sample size is a limitation to the study although there are no indications in our results or among previous studies, that a larger sample size would return different results.

In conclusion, a functional and individualised therapeutic exercise programme had no effects on lower extremity gait biomechanics in people with knee OA. If gait biomechanics are to be changed, future studies should focus on exercise programmes specifically designed to alter gait patterns, or include other measures of mobility, such as stair negotiation or on inclined surfaces.

Footnotes

Contributors: MH is responsible for the integrity of the work.

MH: Conception, design, analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript.

LK: Study coordination, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript.

CB: Intervention delivery, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript.

TS-J: Data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript.

EB: Study coordination, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript.

HB: Conception, design, analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, final approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Health Research Ethics Committee of the Capital Region of Denmark.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Dougados M, Leclaire P, van der Heijde D, et al. Response criteria for clinical trials on osteoarthritis of the knee and hip: a report of the osteoarthritis research society international standing committee for clinical trials response criteria initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2000;8:395–403. 10.1053/joca.2000.0361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: oarsi evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:137–62. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bennell KL, Hunt MA, Wrigley TV, et al. Hip strengthening reduces symptoms but not knee load in people with medial knee osteoarthritis and Varus malalignment: a randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:621–8. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foroughi N, Smith RM, Lange AK, et al. Lower limb muscle strengthening does not change frontal plane moments in women with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Biomech 2011;26:167–74. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bennell KL, Dobson F, Roos EM, et al. Influence of biomechanical characteristics on pain and function outcomes from exercise in medial knee osteoarthritis and Varus malalignment: exploratory analyses from a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:1281–8. 10.1002/acr.22558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foroughi N, Smith RM, Lange AK, et al. Progressive resistance training and dynamic alignment in osteoarthritis: a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Clin Biomech 2011;26:71–7. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2010.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim BW, Hinman RS, Wrigley TV, et al. Does knee malalignment mediate the effects of quadriceps strengthening on knee adduction moment, pain, and function in medial knee osteoarthritis? A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:943–51. 10.1002/art.23823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McGibbon CA, Krebs DE, Scarborough DM. Rehabilitation effects on compensatory gait mechanics in people with arthritis and strength impairment. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:248–54. 10.1002/art.11005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Henriksen M, Klokker L, Graven-Nielsen T, et al. Association of exercise therapy and reduction of pain sensitivity in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1836–43. 10.1002/acr.22375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]