Abstract

AIM

To detect the expression of threonine and tyrosine kinase (TTK) in gallbladder cancer (GBC) specimens and analyze the associations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters and clinical prognosis.

METHODS

A total of 68 patients with GBC who underwent surgical resection were enrolled in this study. The expression of TTK in GBC tissues was detected by immunohistochemistry. The assessment of TTK expression was conducted using the H-scoring system. H-score was calculated by the multiplication of the overall staining intensity with the percentage of positive cells. The expression of TTK in the cytoplasm and nucleus was scored separately to achieve respective H-score values. The correlations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters and clinical prognosis were analyzed using Chi-square test, Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression.

RESULTS

In both the nucleus and cytoplasm, the expression of TTK in tumor tissues was significantly lower than that in normal tissues (P < 0.001 and P = 0.026, respectively). Using the median H-score as the cutoff value, it was discovered that, GBC patients with higher levels of TTK expression in the nucleus, but not the cytoplasm, had favorable overall survival (P < 0.001), and it was still statistically meaningful in Cox regression analysis. Further investigation indicated that there were close negative correlations between TTK expression and tumor differentiation (P = 0.041), CA 19-9 levels (P = 0.016), T stage (P < 0.001), nodal involvement (P < 0.001), distant metastasis (P = 0.024) and TNM stage (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION

The expression of TTK in GBC is lower than that in normal tissues. Higher levels of TTK expression in GBC are concomitant with longer overall survival. TTK is a favorable prognostic biomarker for patients with GBC.

Keywords: Threonine and tyrosine kinase, Biomarker, Prognosis, Gallbladder cancer

Core tip: Numerous studies demonstrate that high levels of threonine and tyrosine kinase (TTK) are present in many types of human malignancies, and its overexpression closely correlates with early recurrence and poor survival. However, no prior studies have attempted to concentrate on the expression of TTK in patients with gallbladder cancer (GBC). In this study, we detected the expression of TTK in GBC specimens and analyzed the associations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters and clinical prognosis.

INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is the most common malignancy of the biliary tract. As a potentially lethal disease, GBC has a dismal prognosis, with a median survival of 3-11 mo and a 5-year survival of 3%-13%[1]. Prolonged survival and better prognosis could be primarily seen in a small group of patients with incidental gallbladder cancer (IGBC), but this fortunate scenario exists in only 0.3%-2% of all performed cholecystectomies due to benign conditions or after cholecystectomy[2,3]. The incidence of GBC is characterized by remarkable geographical variations and ethnic disparities, with an extraordinarily high occurrence in Chile, Japan, and northern India[4]. The incidence of GBC is quite low in most Western countries and thus it is referred to as an orphan disease in the United States[5]. However, with increasing global migration, the incidence of GBC in the West is on the rise, making it a global disease and afflicting thousands of individuals worldwide. Currently, radical surgical resection remains to be the mainstay treatment to extend the life expectancy for eligible patients. There are few chemotherapeutic agents for patients with GBC and there are low response rates to adjuvant treatments.

The spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) is a safeguard mechanism that functions to monitor improperly oriented chromosomes, generate correct bipolar attachments to the spindle and minimize chromosome missegregation errors prior to anaphase onset[6,7]. Threonine and tyrosine kinase (TTK) is a dual-specificity protein kinase capable of phosphorylating threonines/serines and tyrosines[8]. It is the core component and major regulator of the SAC, which is able to recruit and orchestrate other SAC protein kinases to the kinetochore, thereby ensuring faithful chromosome segregation and maintaining genome stability[9,10]. Increased TTK levels are readily discovered in many types of human tumors, including glioblastoma, thyroid carcinoma, breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, pancreatic cancer as well as prostate cancer, and TTK overexpression closely correlates with early recurrence and poor survival[11-23]. We reviewed the relevant clinical research and trials concerning TTK in several human cancers[24], however, no prior studies were found regarding the expression of TTK in patients with GBC. In this study, we detected the expression of TTK in GBC specimens and analyzed the associations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters and clinical prognosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and tissue specimens

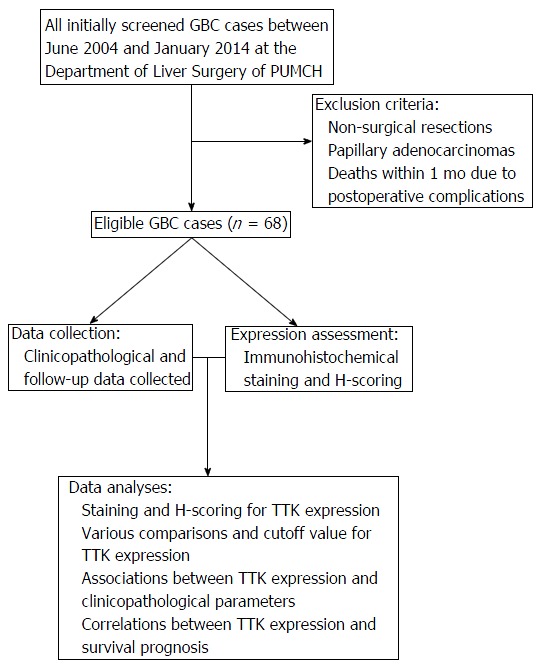

Sixty-eight cases were selected retrospectively from patients with GBC who underwent surgical resection at the Department of Liver Surgery of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) between June 2004 and January 2014 (Figure 1). Sixty-eight pairs of GBC specimens and adjacent normal tissue specimens were acquired from these patients. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before surgery, and surgical procedures were performed according to the approved guidelines. Surgical types were categorized as curative and noncurative resections. Curative resection (R0) referred to en bloc resection with a negative surgical margin, while the presence of microscopic (R1) or macroscopic (R2) residual cancer was considered noncurative. The clinicopathological data were collected from the medical records and the patients were followed from the date of surgery till October 2016. Patients with GBC were staged according to the 7th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer system. The assays for liver function and serum tumor marker were considered positive when concentrations were beyond the normal upper limits. The follow-up data were obtained via outpatient records, phone visits and personal emails. The endpoint was overall survival (OS), defined as the time interval from the date of surgery to the cancer-related death. The study above was approved by the Ethics Committee of PUMCH.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study. A total of 68 cases were enrolled in the study, with explicit exclusion criteria. After collecting clinicopathological and follow-up data and conducting immunohistochemistry staining, correlations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters and survival prognosis were analyzed. GBC: Gallbladder cancer; PUMCH: Peking Union Medical College Hospital; TTK: Threonine and tyrosine kinase.

Immunohistochemistry and H-scoring for TTK

All fresh tissue specimens were collected and immersed into 10% neutral-buffered formalin solution after immediate surgical resection and then embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 5 μm and stained immunohistochemically. Immunohistochemical staining was conducted manually and each slide was strictly processed in accordance with the immunohistochemical protocol. TTK polyclonal antibody (HPA016834, Sigma, the United States, 1:100), produced in rabbit, was used for biomarker expression analysis. High pressure induced antigen retrieval was performed in the PBS buffer solution (pH 7.3), and subsequent TTK staining was carried out for 90 min at the room temperature. Small intestinal tissue was recommended by the manufacturer as a positive control, and staining without the primary antibody was used as a negative control.

The immunohistochemical slides were evaluated independently by two experienced pathologists in a blinded fashion. The assessment of TTK staining was conducted using the H-scoring system[25-28], and H-score was calculated by the multiplication of the overall staining intensity with the percentage of positive cells. The staining intensity was graded from 0 to 3 (0 = negative, 1 = weak, 2 = medium, 3 = strong) and the positive percentage increased from 0 to 100. Theoretically, the final H-score values were obtained with a range from 0 to 300. TTK staining in the cytoplasm and nucleus was scored separately to achieve respective values.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 software (Chicago, IL, United States). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the distribution of the data and to decide the selection of statistical method. Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative variables and Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the abnormally distributed variables. Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test were used to compare OS. All potential prognostic factors on univariate analyses were entered into the Cox regression model. Cox regression multivariate analysis was performed further to identify the independent prognostic factors. All P-values were two sided and considered statistically significant when less than 0.05.

RESULTS

Clinicopathological characteristics and survival data

The mean and median ages of patients at surgery were 65 and 66 years (range, 35-79 years), separately. The majority (57.4%) of patients were female and the female:male ratio was 1.3:1. Gallstones were present in 60.3% of cases. Slightly more than half (51.5%) of patients underwent curative resection and moderately to well-differentiated adenocarcinomas were found in 77.9% of cases. Nodal involvement and distant metastasis occurred in 44.1% and 11.8% of patients, respectively. Three cases were completely lost to follow-up after surgery. The median overall follow-up period was 55 mo (range, 27-159 mo). The 1-year and 2-year survival rates were 66.2% and 41.2%, separately. More information about the cohort is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics of the cohort

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Age (yr) | |

| ≤ 65 | 33 (48.5) |

| > 65 | 35 (51.5) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 39 (57.4) |

| Male | 29 (42.6) |

| Cholecystolithiasis | |

| Yes | 41 (60.3) |

| No | 27 (39.7) |

| Diabetes | |

| Yes | 17 (25.0) |

| No | 51 (75.0) |

| Fever | |

| Yes | 9 (13.2) |

| No | 59 (86.8) |

| Jaundice | |

| Yes | 15 (22.1) |

| No | 53 (77.9) |

| ALT | |

| Normal | 53 (77.9) |

| Elevated | 15 (22.1) |

| AST | |

| Normal | 50 (75.8) |

| Elevated | 16 (24.2) |

| TBil | |

| Normal | 49 (72.1) |

| Elevated | 19 (27.9) |

| DBil | |

| Normal | 50 (73.5) |

| Elevated | 18 (26.5) |

| GGT | |

| Normal | 43 (69.4) |

| Elevated | 19 (30.6) |

| ALP | |

| Normal | 45 (72.6) |

| Elevated | 17 (27.4) |

| CEA | |

| Normal | 42 (72.4) |

| Elevated | 16 (27.6) |

| CA 19-9 | |

| Normal | 26 (44.1) |

| Elevated | 33 (55.9) |

| Surgical type | |

| Curative | 35 (51.5) |

| Noncurative | 33 (48.5) |

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| ≤ 3 | 43 (63.2) |

| > 3 | 25 (36.8) |

| Differentiation | |

| Lowly-undifferentiated | 15 (22.1) |

| Moderately-well | 53 (77.9) |

| T stage | |

| Tis | 1 (1.5) |

| T1 | 3 (4.4) |

| T2 | 29 (42.6) |

| T3 | 35 (51.5) |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 38 (55.9) |

| N1 | 22 (32.4) |

| N2 | 8 (11.7) |

| M stage | |

| M0 | 60 (88.2%) |

| M1 | 8 (11.8%) |

| TNM stage | |

| I | 4 (5.9) |

| II | 24 (35.3) |

| IIIA | 9 (13.2) |

| IIIB | 17 (25.0) |

| IVA | 0 (0) |

| IVB | 14 (20.6) |

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; TBil: Total bilirubin; DBil: Direct bilirubin; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; CA 19-9: Carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Staining and H-scoring for TTK expression

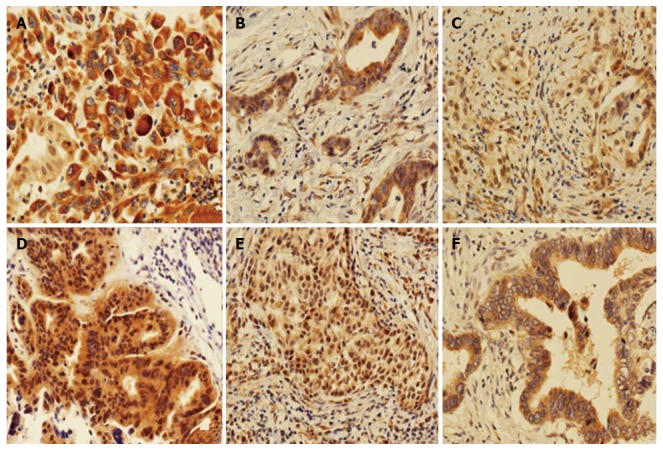

TTK staining was counted and analyzed in the patients (Table 2 and Figure 2). In tumor tissues, all specimens displayed cytoplasmic staining, of which one case was strongly positive (3+); most specimens (88.2%, 60/68) displayed nuclear staining, eight cases exhibited negative nuclear staining, and no strongly positive cases were found among the specimens. While in normal tissues, overall specimens displayed cytoplasmic staining, of which one case was strongly positive (3+); nearly all specimens (97.1%, 66/68) displayed nuclear staining, two cases exhibited negative nuclear staining, and no strong positive cases were found within the specimens.

Table 2.

Threonine and tyrosine kinase staining results in tumor and normal tissues

| Localization | Positive cell rate (%) |

n (%) |

||

|

Median (range) | ||||

| Tumor tissues | Normal tissues | Tumor tissues | Normal tissues | |

| Cytoplasmic staining | ||||

| Negative | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| Positive | 100 (10-100) | 99 (40-100) | 68 (100) | 68 (100) |

| 1+ | 55 (10-100) | 85 (18-100) | 41 (60.3) | 14 (20.6) |

| 2+ | 90 (5-100) | 100 (80-100) | 49 (72.1) | 54 (79.4) |

| 3+ | 20 | 90 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) |

| Nuclear staining | ||||

| Negative | - | - | 8 (11.8) | 2 (2.9) |

| Positive | 15 (1-98) | 60 (1-90) | 60 (88.2) | 66 (97.1) |

| 1+ | 15 (1-85) | 60 (1-90) | 57 (83.8) | 59 (86.8) |

| 2+ | 45 (5-98) | 90 (60-90) | 8 (11.8) | 7 (10.3) |

| 3+ | - | - | 0 | 0 |

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissues (magnification, × 200). A-C: Cytoplasm staining with 3+, 2+ and 1+ intensity, respectively; D-F: Nuclear staining with 2+, 1+ and 0+ intensity, respectively.

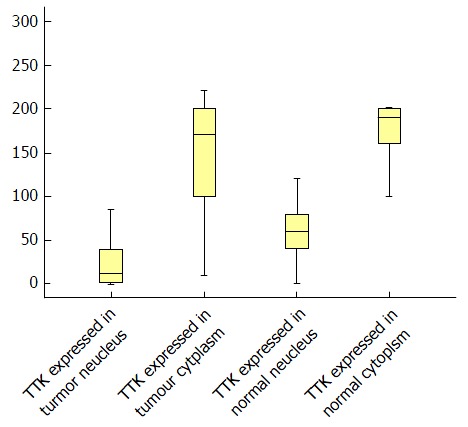

We calculated the H-score in both tumor and normal tissues (Table 3 and Figure 3), and it was found that, in tumor tissues, TTK exhibited a median H-score of 170 (range, 10-220) and 12.5 (range, 0-196) in the cytoplasm and nucleus, separately. While in normal tissues, the median H-scores observed for TTK were 190 (range, 40-270) and 60 (range, 0-180), respectively.

Table 3.

H-score values in tumor and normal tissues

| Group | n | Localization | Minimum | Maximum | Median |

| Tumor | 68 | Nucleus | 0 | 196 | 12.5 |

| 68 | Cytoplasm | 10 | 220 | 170 | |

| Normal | 68 | Nucleus | 0 | 180 | 60 |

| 68 | Cytoplasm | 40 | 270 | 190 |

Figure 3.

Boxplot for H-scores in tumor and normal tissues. TTK: Threonine and tyrosine kinase.

Various comparisons and cutoff value for TTK expression

Indicated by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, the values of H-score were distributed abnormally. Therefore, Mann-Whitney U test was selected to make comparisons for them (Table 4). In both tumor and normal tissues, the expression of TTK in the nucleus was significantly lower than that in the cytoplasm (P < 0.001 for both). Moreover, we found that, in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, there was significantly lower expression of TTK in tumor tissues, compared with normal tissues (P < 0.001 and P = 0.026, respectively).

Table 4.

Various comparisons in tumor and normal tissues for threonine and tyrosine kinase expression

| Group | n | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean rank | P value |

| Comparison between nucleus and cytoplasm in normal tissues | ||||||

| Nucleus | 68 | 0 | 180 | 60 | 39.65 | <0.0011 |

| Cytoplasm | 68 | 40 | 270 | 190 | 97.35 | |

| Comparison between nucleus and cytoplasm in tumor tissues | ||||||

| Nucleus | 68 | 0 | 196 | 12.5 | 38.98 | <0.0011 |

| Cytoplasm | 68 | 10 | 220 | 170 | 98.02 | |

| Comparison between tumor and normal tissues in nucleus | ||||||

| Tumor | 68 | 0 | 196 | 12.5 | 49.54 | <0.0011 |

| Normal | 68 | 0 | 180 | 60 | 87.46 | |

| Comparison between tumor and normal tissues in cytoplasm | ||||||

| Tumor | 68 | 10 | 220 | 170 | 61.19 | 0.0261 |

| Normal | 68 | 40 | 270 | 190 | 75.81 | |

Statistically significant.

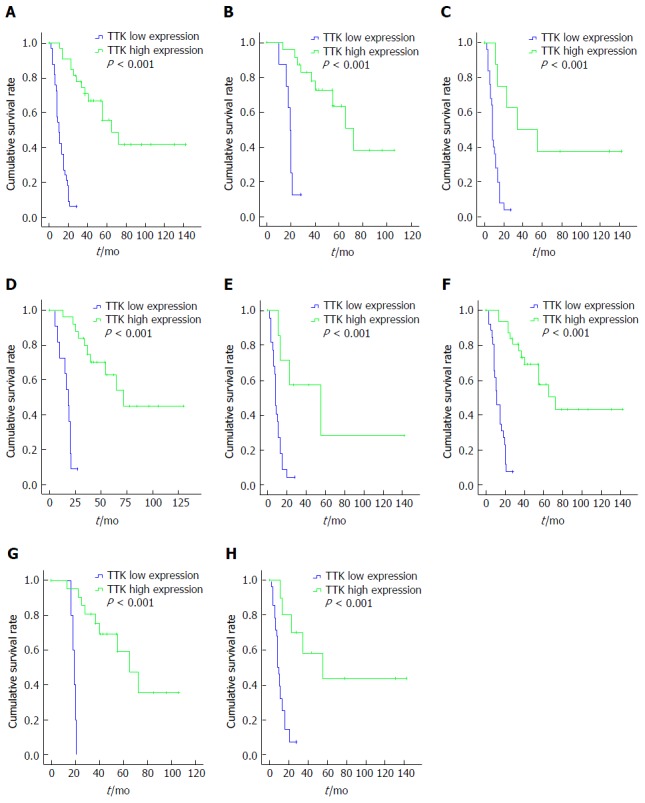

For patients with GBC, the population was divided into two groups according to the median H-score values of the nuclear and cytoplasmic staining. Surprisingly, we found that, patients with higher H-score values in the nucleus, but not the cytoplasm, had favorable OS (Figure 4A), and it was still statistically meaningful in Cox regression multivariate analysis (Table 5). Thus, the median nuclear H-score was used as the discriminating threshold[29] and the cutoff value was set at 12.5.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival analyses in different subgroups, according to threonine and tyrosine kinase expression. A: The whole cohort; B: T1 + 2 group; C: T3 group; D: Negative nodal involvement group; E: Positive nodal involvement group; F: Free distant metastasis group; G: Stage I + II group; H: Stage III + IV group.TTK: Threonine and tyrosine kinase.

Table 5.

Univariate and multivariate analyses for gallbladder cancer

| χ2 | P value | OR (95%CI) | |

| Univariate | |||

| Age | 2.221 | 0.136 | |

| Gender | 0.167 | 0.683 | |

| Cholecystolithiasis | 0.346 | 0.558 | |

| Diabetes | 0.165 | 0.685 | |

| Fever | 0.001 | 0.989 | |

| Jaundice1 | 5.110 | 0.0241 | |

| ALT1 | 7.781 | 0.0051 | |

| AST1 | 5.708 | 0.0171 | |

| TBil | 0.241 | 0.516 | |

| DBil1 | 6.645 | 0.0101 | |

| GGT | 0.899 | 0.343 | |

| ALP1 | 4.099 | 0.0431 | |

| CEA | 3.137 | 0.077 | |

| CA 19-91 | 12.385 | < 0.0011 | |

| Surgical type1 | 20.715 | < 0.0011 | |

| Tumor size | 0.099 | 0.754 | |

| Differentiation1 | 12.385 | < 0.0011 | |

| T stage1 | 21.594 | < 0.0011 | |

| N stage1 | 19.887 | < 0.0011 | |

| M stage1 | 29.503 | < 0.0011 | |

| TNM stage1 | 33.062 | < 0.0011 | |

| TTK1 | 21.226 | < 0.0011 | |

| Multivariate | |||

| Surgery type1 | 0.0011 | 4.250 (1.867-9.674) | |

| T stage1 | 0.0131 | 2.927 (1.258-6.808) | |

| TTK1 | 0.0011 | 0.076 (0.024-0.241) |

Statistically significant. ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; TTK: Threonine and tyrosine kinase.

Correlations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters

The correlations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters are detailed in Table 6. There were no significant associations between TTK expressions and age, gender, tumor size or CEA levels. However, TTK expression exhibited significant negative correlations with tumor differentiation (P = 0.041), CA 19-9 levels (P = 0.016), T stage (P < 0.001), nodal involvement (P < 0.001), distant metastasis (P = 0.024) and TNM stage (P < 0.001). Higher TTK expression rates were observed in patients with normal CA 19-9 levels, moderately to well-differentiated tumors, T stages 1 + 2, negative nodal involvement, free distant metastasis and TNM stages I + II, in contrast to the ones with elevated CA 19-9 levels, lowly to undifferentiated tumors, T stage 3, positive nodal involvement, distant metastasis and TNM stages III + IV, respectively.

Table 6.

Correlations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters

| Parameter |

TTK expression |

χ2 | P-value | |

| Low expression | High expression | |||

| Age (yr) | ||||

| ≤ 65 | 16 | 17 | 0.059 | 0.808 |

| > 65 | 18 | 17 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 20 | 19 | 0.277 | 0.598 |

| Male | 13 | 16 | ||

| CEA | ||||

| Normal | 20 | 22 | 3.512 | 0.061 |

| Elevated | 12 | 4 | ||

| CA 19-91 | ||||

| Normal | 10 | 16 | 5.756 | 0.0161 |

| Elevated | 23 | 10 | ||

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤ 3 | 22 | 21 | 0.063 | 0.801 |

| > 3 | 12 | 13 | ||

| Differentiation1 | ||||

| Lowly-undifferentiated | 11 | 4 | 4.191 | 0.0411 |

| Moderately-well | 23 | 30 | ||

| T stage1 | ||||

| 1 + 2 | 8 | 25 | 17.015 | < 0.0011 |

| 3 | 26 | 9 | ||

| Nodal involvement1 | ||||

| Negative | 12 | 26 | 11.691 | < 0.0011 |

| Positive | 22 | 8 | ||

| Metastasis1 | ||||

| M0 | 27 | 33 | 5.100 | 0.0241 |

| M1 | 7 | 1 | ||

| TNM stage 1 | ||||

| I + II | 5 | 23 | 19.671 | < 0.0011 |

| III + IV | 29 | 11 | ||

Statistically significant. CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; TTK: Threonine and tyrosine kinase.

Survival analysis

Clinical follow-up data were available among 65 of the 68 patients. Univariate survival analysis (Table 5) revealed that TTK expression (P < 0.001), jaundice (P = 0.024), concentrations of ALT (P = 0.005), AST (P = 0.017), ALP (P = 0.043), DBil (P = 0.010), CA 19-9 (P < 0.001), surgical type (P < 0.001), tumor differentiation (P < 0.001), T (P < 0.001), N (P < 0.001), M (P < 0.001) and TNM stages (P < 0.001) were associated with OS in patients with GBC, while age, gender, fever, cholecystolithiasis, diabetes, concentrations of TBil, GGT and CEA had no significant influence on the survival in our study.

Cox regression multivariate analysis revealed that surgical type, T stage and TTK expression were independent prognostic factors for OS (Table 5). Further, subgroup analysis by log-rank test indicated that patients with higher levels of TTK expression had longer OS and better prognosis, regardless of T, N, M, or TNM stage, in comparison with the ones with lower TTK expression (Figure 4 B-H).

DISCUSSION

On account of its critical role in maintaining chromosome stability, an increasing number of researchers have concentrated on the relationship between TTK and cancer. While TTK has been studied in many types of malignancies, no prior research has been found regarding its expression and clinical prognosis, in GBC.

In the present study, it was discovered that, the overall expression of TTK in tumor tissues was significantly lower than that in normal tissues, and GBC patients with higher TTK expression had a better prognosis. By contrast, TTK overexpression was found in numerous neoplasms, where they were concomitant with a worse prognosis. Consistent with our results, Xu et al[30] also found that increased TTK expression was related with prolonged disease free survival and OS in triple-negative breast cancer, but without comparisons between tumor and normal tissues. It may be suggested that TTK plays a certain role in the initiation of GBC. TTK is required for the execution of the SAC machinery during mitosis and conductive to the fidelity of chromosome segregations at the kinetochores. The inhibition of TTK activity could therefore compromise the function of the SAC and culminate in undesirable effects, including chromosomal instability (CIN), aneuploidy formation, cell death or carcinogenesis[31-35]. It is widely accepted that chromosomal instability is correlative with intratumor heterogeneity, chromosome aberrations and aneuploidy formations. In fact, aneuploidy has been found at the earliest stages of carcinogenesis and CIN is considered a fundamental process for cancer development[36]. So far, a premature termination of TTK synthesis, due to cancer-associated frameshift mutations, has been frequently found in gastric and colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability[37]. Whether the same process takes place in GBC remains to be explored afterwards.

Apart from the variances between tumor and normal tissues, it was revealed in our current study that there were significant negative correlations between TTK expression and tumor differentiation, T, N, M as well as TNM stages. Furthermore, it was discovered that lower levels of TTK expressions were more helpful for cancer infiltration, nodal involvement and distant metastasis. Patients with higher levels of TTK expression at the same stage had a longer OS than those with lower levels of TTK expression. Thus, TTK may serve as a positive biomarker indicative of prognosis and make a strategic choice for clinicians. For instance, patients with higher levels of TTK expression perhaps could benefit better from the adjuvant chemo- or radio-therapy, in contrast to the ones with lower expression. The use of TTK expression may be more important for patients with IGBC. Currently, the management of IGBC is primarily dictated by T stage alone, with a re-resection recommendation for T1b, T2, or T3 disease[38]. In terms of T1a patients, simple laparoscopic cholecystectomy is sufficient, with a 5-year survival rate of 95.5%[39]. If lower levels of TTK expression are detected in cancer specimens, more attention should be paid to these patients, due to a larger likelihood of nodal involvement and distant metastasis in the future. The survival of the remaining 4.5% of patients may be improved, with a combination of routine pathology and TTK expression.

Of note, our study may provide theoretical support for immunotherapy and targeted therapy in different tumors concerning TTK. TTK has been utilized as an immunogenic epitope to elicit potent and peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity against cancer cells. Its safety, immunogenicity and clinical response have been validated in some clinical trials, including lung cancer, esophageal cancer and biliary tract cancer[40-46]. Even, in a variety of human tumors, TTK has been used as a therapeutic target for innovative approaches in combating the malignancies, involving glioblastoma, breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer[11,12,14-16,18-21]. TTK inhibitors could give rise to attenuated aggressiveness, reduced viability, augmented autophagy and increased apoptosis in these cancers. Further, phase I clinical trials of oral TTK inhibitors (BAY1161909, BAY1217389) have been performed in breast cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT02138812, NCT02366949). In terms of these tumors above, TTK overexpression is exploited and TTK-targeted therapies are available. Nevertheless, it should be cautious for these therapies applied in GBC, due to the low TTK expression.

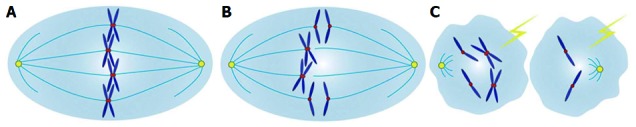

To date, some mechanisms have been revealed in several tumors, concerning TTK and neoplasia. It was unveiled that, in hepatocellular carcinoma, demethylations of TTK promoters were conducive to its overexpression and highly expressed TTK could activate the Akt/mTOR pathway in a p53 dependent fashion[18]. Moreover, in melanoma, TTK/AKT and B-RafWT/ERK signaling constituted an auto-regulatory negative feedback loop together, and continuous phosphorylations of TTK through oncogenic B-RafV600E signaling were able to abrogate the negative feedback loop, leading to aberrant SAC function and tumorigenesis[47,48]. It was discovered that, in breast cancer, high levels of TTK expression were protective for aneuploidy and enabled these cells to tolerate aneuploidy[49]. While in colon cancer, overexpressed TTK could increase aneuploidy, owing to a weakened SAC function, and contribute to carcinogenesis[50]. Among studies available in the literature, it was demonstrated that overexpression of TTK correlated positively with tumor grades and poor survival. Conversely, it was indicated in our study that, lower expression of TTK correlated closely with tumor grade and dismal prognosis. Taken together, aberrant TTK expression, either increased or decreased expression, is clearly correlated with tumorigenesis, which may result from chromosomal instabilities and aneuploidy formations, as a result of compromised SAC functions (Figure 5). Therefore, TTK may play different roles in disparate malignancies, and more thorough research studies are still encouraged to verify the exact relationships between TTK and cancers, as well as the subtle mechanisms.

Figure 5.

Diagram for possible mechanism concerning threonine and tyrosine kinase and carcinogenesis. A: Sister chromatids are properly arrayed in the equatorial plate at metaphase, with correct attachments to microtubules by kinetochores, attributed to the normal spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) safeguard mechanism; B: Aberrant TTK expression, either increased or decreased expressions, could definitely compromise the functions of the SAC, with frequent chromosome missegregation errors; C: Severe chromosome missegregation errors, due to the override of SAC function, could result in chromosomal instabilities, aneuploidy formations, cell deaths and carcinogenesis; TTK: Threonine and tyrosine kinase.

Recently, it has been found that TP53, KRAS and ERBB3 are the most frequent somatic mutations in the GBC spectrum[51]. Additionally, striking progress has been made in the clarification of emergent intracellular signaling pathways, such as Hedgehog, PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Notch, which are activated in GBC[52]. These promising studies may provide valuable clues for the deep insight into the roles that TTK plays in GBC.

Our study has several limitations. Primarily, the study was retrospective, and all the information of each patient was collected from medical records, which may contribute to the selection bias. Next, it was a single-institutional investigation and the number of cases was relatively small, restricting the power of statistical analysis. Finally, some patients received postoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and the effects of these adjuvant therapies on prognosis were not considered, in spite of limited survival benefits brought by them. For these reasons above, multi-institutional investigations and prospective studies are required to explore the expression of TTK in GBC, and further evaluate its clinical significance in a larger cohort of patients.

In conclusion, our data suggest that the expression of TTK in GBC is lower than that in normal tissues. Higher levels of TTK expression are concomitant with longer overall survival in GBC. TTK is a favorable prognostic biomarker for patients with GBC.

COMMENTS

Background

Threonine and tyrosine kinase (TTK) is a dual-specificity protein kinase capable of phosphorylating threonines/serines and tyrosines. It is the core component and major regulator of the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC), which functions to ensure faithful chromosome segregation and maintain genome stability. Increased TTK levels could be readily discovered in many types of human tumors, including glioblastoma, thyroid carcinoma and breast cancer, and its overexpression closely correlates with early recurrence and poor survival. However, no prior studies were found regarding the expression of TTK in patients with gallbladder cancer (GBC). In this study, we detected the expression of TTK in GBC specimens and analyzed the associations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters and clinical prognosis.

Research frontiers

Numerous studies demonstrate that high levels of TTK are present in many types of human malignancies, and its overexpression closely correlates with early recurrence and poor survival. Several TTK inhibitors have been developed to combat the malignancies and they exhibit demonstrable survival benefits. Moreover, TTK has been used as an immunogenic epitope to elicit potent and peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity against cancer cells. Its safety, immunogenicity and clinical response have been validated in several clinical trials.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The results demonstrate that the expression of TTK in gallbladder cancer is lower than that in normal tissues. Higher levels of TTK expression are concomitant with longer overall survival in GBC. TTK is a favorable prognostic biomarker for patients with GBC.

Applications

This study suggests that TTK may serve as a positive biomarker indicative of prognosis, and it may also provide theoretical support for the immunotherapy and targeted therapy in different tumors concerning TTK.

Terminology

The SAC is a safeguard mechanism that functions to monitor improperly oriented chromosomes, generate correct bipolar attachments to the spindle and minimize chromosome missegregation errors prior to anaphase onset. TTK is a dual-specificity protein kinase that phosphorylates threonines/serines and tyrosines. TTK acts as the core component and major regulator of the SAC, which functions to recruit and orchestrate other SAC protein kinases to the kinetochore, thereby ensuring faithful chromosome segregation and maintaining genome stability.

Peer-review

This is an interesting study about the TTK in GBC. In this study, the authors investigated the expression of TTK in GBC specimens and the associations between TTK expression and clinicopathological parameters and clinical prognosis. The authors found that using the median H-score as the cutoff value, patients with higher levels of TTK expression in the nucleus had favorable overall survival. This study is overall well-designed and the manuscript is very well-written.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: The publication of this manuscript has been reviewed and approved by the PUMCH Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement: All patients or their families signed informed consent statements before surgery, and surgical procedures were performed according to the approved guidelines.

Conflict-of-interest statement: We declare that the authors have no conflict of interest.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: May 31, 2017

First decision: June 22, 2017

Article in press: July 12, 2017

P- Reviewer: Deepak P, Zimmerman M S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Huang Y

Contributor Information

Yuan Xie, Department of Liver Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Jian-Zhen Lin, Department of Liver Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

An-Qiang Wang, Department of Liver Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Wei-Yu Xu, Department of Liver Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Jun-Yu Long, Department of Liver Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Yu-Feng Luo, Department of Pathology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China..

Jie Shi, Department of Pathology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China..

Zhi-Yong Liang, Department of Pathology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China..

Xin-Ting Sang, Department of Liver Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China.

Hai-Tao Zhao, Department of Liver Surgery, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China. zhaoht@pumch.cn.

References

- 1.Cubertafond P, Gainant A, Cucchiaro G. Surgical treatment of 724 carcinomas of the gallbladder. Results of the French Surgical Association Survey. Ann Surg. 1994;219:275–280. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199403000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinert R, Nestler G, Sagynaliev E, Müller J, Lippert H, Reymond MA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and gallbladder cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:682–689. doi: 10.1002/jso.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon AH, Imamura A, Kitade H, Kamiyama Y. Unsuspected gallbladder cancer diagnosed during or after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:241–245. doi: 10.1002/jso.20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:99–109. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S37357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy AD, Murakata LA, Rohrmann CA Jr. Gallbladder carcinoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2001;21:295–314; questionnaire, 549-555. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.2.g01mr16295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lara-Gonzalez P, Westhorpe FG, Taylor SS. The spindle assembly checkpoint. Curr Biol. 2012;22:R966–R980. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vleugel M, Hoogendoorn E, Snel B, Kops GJ. Evolution and function of the mitotic checkpoint. Dev Cell. 2012;23:239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisk HA, Mattison CP, Winey M. A field guide to the Mps1 family of protein kinases. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:439–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sacristan C, Kops GJ. Joined at the hip: kinetochores, microtubules, and spindle assembly checkpoint signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santaguida S, Amon A. Short- and long-term effects of chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:473–485. doi: 10.1038/nrm4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tannous BA, Kerami M, Van der Stoop PM, Kwiatkowski N, Wang J, Zhou W, Kessler AF, Lewandrowski G, Hiddingh L, Sol N, et al. Effects of the selective MPS1 inhibitor MPS1-IN-3 on glioblastoma sensitivity to antimitotic drugs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1322–1331. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maachani UB, Kramp T, Hanson R, Zhao S, Celiku O, Shankavaram U, Colombo R, Caplen NJ, Camphausen K, Tandle A. Targeting MPS1 Enhances Radiosensitization of Human Glioblastoma by Modulating DNA Repair Proteins. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:852–862. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0462-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvatore G, Nappi TC, Salerno P, Jiang Y, Garbi C, Ugolini C, Miccoli P, Basolo F, Castellone MD, Cirafici AM, et al. A cell proliferation and chromosomal instability signature in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10148–10158. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maire V, Baldeyron C, Richardson M, Tesson B, Vincent-Salomon A, Gravier E, Marty-Prouvost B, De Koning L, Rigaill G, Dumont A, et al. TTK/hMPS1 is an attractive therapeutic target for triple-negative breast cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Győrffy B, Bottai G, Lehmann-Che J, Kéri G, Orfi L, Iwamoto T, Desmedt C, Bianchini G, Turner NC, de Thè H, et al. TP53 mutation-correlated genes predict the risk of tumor relapse and identify MPS1 as a potential therapeutic kinase in TP53-mutated breast cancers. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:508–519. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maia AR, de Man J, Boon U, Janssen A, Song JY, Omerzu M, Sterrenburg JG, Prinsen MB, Willemsen-Seegers N, de Roos JA, et al. Inhibition of the spindle assembly checkpoint kinase TTK enhances the efficacy of docetaxel in a triple-negative breast cancer model. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2180–2192. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao R, Luo H, Zhou H, Li G, Bu D, Yang X, Zhao X, Zhang H, Liu S, Zhong Y, et al. Identification of prognostic biomarkers in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma and stratification by integrative multi-omics analysis. J Hepatol. 2014;61:840–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Liao W, Yuan Q, Ou Y, Huang J. TTK activates Akt and promotes proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:34309–34320. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miao R, Wu Y, Zhang H, Zhou H, Sun X, Csizmadia E, He L, Zhao Y, Jiang C, Miksad RA, et al. Utility of the dual-specificity protein kinase TTK as a therapeutic target for intrahepatic spread of liver cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33121. doi: 10.1038/srep33121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slee RB, Grimes BR, Bansal R, Gore J, Blackburn C, Brown L, Gasaway R, Jeong J, Victorino J, March KL, et al. Selective inhibition of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell growth by the mitotic MPS1 kinase inhibitor NMS-P715. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:307–315. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaistha BP, Honstein T, Müller V, Bielak S, Sauer M, Kreider R, Fassan M, Scarpa A, Schmees C, Volkmer H, et al. Key role of dual specificity kinase TTK in proliferation and survival of pancreatic cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1780–1787. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shiraishi T, Terada N, Zeng Y, Suyama T, Luo J, Trock B, Kulkarni P, Getzenberg RH. Cancer/Testis Antigens as potential predictors of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy. J Transl Med. 2011;9:153. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahlman KB, Parker JS, Shamu T, Hieronymus H, Chapinski C, Carver B, Chang K, Hannon GJ, Sawyers CL. Modulators of prostate cancer cell proliferation and viability identified by short-hairpin RNA library screening. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Y, Wang A, Lin J, Wu L, Zhang H, Yang X, Wan X, Miao R, Sang X, Zhao H. Mps1/TTK: a novel target and biomarker for cancer. J Drug Target. 2017;25:112–118. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2016.1258568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeo W, Chan SL, Mo FK, Chu CM, Hui JW, Tong JH, Chan AW, Koh J, Hui EP, Loong H, et al. Phase I/II study of temsirolimus for patients with unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)- a correlative study to explore potential biomarkers for response. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:395. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1334-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Specht E, Kaemmerer D, Sänger J, Wirtz RM, Schulz S, Lupp A. Comparison of immunoreactive score, HER2/neu score and H score for the immunohistochemical evaluation of somatostatin receptors in bronchopulmonary neuroendocrine neoplasms. Histopathology. 2015;67:368–377. doi: 10.1111/his.12662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang PI, Li CF, Chen LT, Sun DP, Chen TJ, Hsing CH, Hsu HP, Lin CY. BCL6 overexpression is associated with decreased p19 ARF expression and confers an independent prognosticator in gallbladder carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:1417–1426. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Budwit-Novotny DA, McCarty KS, Cox EB, Soper JT, Mutch DG, Creasman WT, Flowers JL, McCarty KS Jr. Immunohistochemical analyses of estrogen receptor in endometrial adenocarcinoma using a monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5419–5425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Christoph DC, Kasper S, Gauler TC, Loesch C, Engelhard M, Theegarten D, Poettgen C, Hepp R, Peglow A, Loewendick H, et al. βV-tubulin expression is associated with outcome following taxane-based chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:823–830. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Q, Xu Y, Pan B, Wu L, Ren X, Zhou Y, Mao F, Lin Y, Guan J, Shen S, et al. TTK is a favorable prognostic biomarker for triple-negative breast cancer survival. Oncotarget. 2016;7:81815–81829. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombo R, Caldarelli M, Mennecozzi M, Giorgini ML, Sola F, Cappella P, Perrera C, Depaolini SR, Rusconi L, Cucchi U, et al. Targeting the mitotic checkpoint for cancer therapy with NMS-P715, an inhibitor of MPS1 kinase. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10255–10264. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hewitt L, Tighe A, Santaguida S, White AM, Jones CD, Musacchio A, Green S, Taylor SS. Sustained Mps1 activity is required in mitosis to recruit O-Mad2 to the Mad1-C-Mad2 core complex. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:25–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201002133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jemaà M, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Senovilla L, Brands M, Boemer U, Koppitz M, Lienau P, Prechtl S, Schulze V, et al. Characterization of novel MPS1 inhibitors with preclinical anticancer activity. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:1532–1545. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwiatkowski N, Jelluma N, Filippakopoulos P, Soundararajan M, Manak MS, Kwon M, Choi HG, Sim T, Deveraux QL, Rottmann S, et al. Small-molecule kinase inhibitors provide insight into Mps1 cell cycle function. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:359–368. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dodson CA, Haq T, Yeoh S, Fry AM, Bayliss R. The structural mechanisms that underpin mitotic kinase activation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2013;41:1037–1041. doi: 10.1042/BST20130066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danielsen HE, Pradhan M, Novelli M. Revisiting tumour aneuploidy - the place of ploidy assessment in the molecular era. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:291–304. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn CH, Kim YR, Kim SS, Yoo NJ, Lee SH. Mutational analysis of TTK gene in gastric and colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res Treat. 2009;41:224–228. doi: 10.4143/crt.2009.41.4.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ethun CG, Postlewait LM, Le N, Pawlik TM, Buettner S, Poultsides G, Tran T, Idrees K, Isom CA, Fields RC, et al. A Novel Pathology-Based Preoperative Risk Score to Predict Locoregional Residual and Distant Disease and Survival for Incidental Gallbladder Cancer: A 10-Institution Study from the U.S. Extrahepatic Biliary Malignancy Consortium. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:1343–1350. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5637-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian YH, Ji X, Liu B, Yang GY, Meng XF, Xia HT, Wang J, Huang ZQ, Dong JH. Surgical treatment of incidental gallbladder cancer discovered during or following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 2015;39:746–752. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2864-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suda T, Tsunoda T, Daigo Y, Nakamura Y, Tahara H. Identification of human leukocyte antigen-A24-restricted epitope peptides derived from gene products upregulated in lung and esophageal cancers as novel targets for immunotherapy. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1803–1808. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki H, Fukuhara M, Yamaura T, Mutoh S, Okabe N, Yaginuma H, Hasegawa T, Yonechi A, Osugi J, Hoshino M, et al. Multiple therapeutic peptide vaccines consisting of combined novel cancer testis antigens and anti-angiogenic peptides for patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Transl Med. 2013;11:97. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizukami Y, Kono K, Daigo Y, Takano A, Tsunoda T, Kawaguchi Y, Nakamura Y, Fujii H. Detection of novel cancer-testis antigen-specific T-cell responses in TIL, regional lymph nodes, and PBL in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1448–1454. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kono K, Mizukami Y, Daigo Y, Takano A, Masuda K, Yoshida K, Tsunoda T, Kawaguchi Y, Nakamura Y, Fujii H. Vaccination with multiple peptides derived from novel cancer-testis antigens can induce specific T-cell responses and clinical responses in advanced esophageal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1502–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kono K, Iinuma H, Akutsu Y, Tanaka H, Hayashi N, Uchikado Y, Noguchi T, Fujii H, Okinaka K, Fukushima R, et al. Multicenter, phase II clinical trial of cancer vaccination for advanced esophageal cancer with three peptides derived from novel cancer-testis antigens. J Transl Med. 2012;10:141. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iinuma H, Fukushima R, Inaba T, Tamura J, Inoue T, Ogawa E, Horikawa M, Ikeda Y, Matsutani N, Takeda K, et al. Phase I clinical study of multiple epitope peptide vaccine combined with chemoradiation therapy in esophageal cancer patients. J Transl Med. 2014;12:84. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aruga A, Takeshita N, Kotera Y, Okuyama R, Matsushita N, Ohta T, Takeda K, Yamamoto M. Long-term Vaccination with Multiple Peptides Derived from Cancer-Testis Antigens Can Maintain a Specific T-cell Response and Achieve Disease Stability in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2224–2231. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Cheng X, Zhang Y, Li S, Cui H, Zhang L, Shi R, Zhao Z, He C, Wang C, et al. Phosphorylation of Mps1 by BRAFV600E prevents Mps1 degradation and contributes to chromosome instability in melanoma. Oncogene. 2013;32:713–723. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang L, Shi R, He C, Cheng C, Song B, Cui H, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Bi Y, Yang X, et al. Oncogenic B-Raf(V600E) abrogates the AKT/B-Raf/Mps1 interaction in melanoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;337:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daniel J, Coulter J, Woo JH, Wilsbach K, Gabrielson E. High levels of the Mps1 checkpoint protein are protective of aneuploidy in breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5384–5389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ling Y, Zhang X, Bai Y, Li P, Wei C, Song T, Zheng Z, Guan K, Zhang Y, Zhang B, et al. Overexpression of Mps1 in colon cancer cells attenuates the spindle assembly checkpoint and increases aneuploidy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450:1690–1695. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li M, Zhang Z, Li X, Ye J, Wu X, Tan Z, Liu C, Shen B, Wang XA, Wu W, et al. Whole-exome and targeted gene sequencing of gallbladder carcinoma identifies recurrent mutations in the ErbB pathway. Nat Genet. 2014;46:872–876. doi: 10.1038/ng.3030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bizama C, García P, Espinoza JA, Weber H, Leal P, Nervi B, Roa JC. Targeting specific molecular pathways holds promise for advanced gallbladder cancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:222–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]