Abstract

Early-life adversity is known to disrupt behavioral trajectories and many rodent models have been developed to characterize these stress-induced outcomes. One example is the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources. This model employs resource scarcity (i.e., low nesting materials) to elicit adverse caregiving conditions (including maltreatment) toward rodent neonates. Our lab utilizes a version of this model wherein caregiving exposures occur outside the home cage during the first postnatal week. The aim of this study was to determine adolescent and adult phenotypic outcomes associated with this model, including assessment of depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors and performance in different cognitive domains. Exposure to adverse caregiving had no effect on adolescent behavioral performance whereas exposure significantly impaired adult behavioral performance. Further, adult behavioral assays revealed substantial differences between sexes. Overall, data demonstrate the ability of repeated exposure to brief bouts of maltreatment outside the home cage in infancy to impact the development of several behavioral domains later in life.

Keywords: early-life stress, early-life adversity, maltreatment, Long-Evans, infancy, adolescence, adulthood, behavioral outcomes

Adversity early in development is known to disrupt typical behavioral trajectories in both rodents (Anier et al., 2014; Kundakovic, Lim, Gudsnuk, & Champagne, 2013; Pan, Fleming, Lawson, Jenkins, & McGowan, 2014) and humans (Agid et al., 1999; Cicchetti & Toth, 1995; McCrory, De Brito, & Viding, 2012). In rodents this includes increasing depressive- (Lippmann, Bress, Nemeroff, Plotsky, & Monteggia, 2007) and anxiety-like (Sarro, Sullivan, & Barr, 2014) behaviors as well as altering cognitive abilities (Sousa et al., 2014). Early adverse experiences often occur within the context of the caregiving relationship and several rodent models have been developed to study this type of adversity. Some examples include maternal separation (Biggio et al., 2014; Cotella, Mestres Lascano, Franchioni, Levin, & Suárez, 2013; Huot, Plotsky, Lenox, & McNamara, 2002; Zalosnik, Pollano, Trujillo, Suarez, & Durando, 2014), fragmented maternal care (Gilles, Schultz, & Baram, 1996; Ivy, Brunson, Sandman, & Baram, 2008; J Molet et al., 2016; Rice, Sandman, Lenjavi, & Baram, 2008), naturally occurring low levels of maternal care (Beery, McEwen, MacIsaac, Francis, & Kobor, 2016; F. A. Champagne et al., 2004; Weaver et al., 2004), and resource scarcity with adverse caregiving (Raineki, Cortés, Belnoue, & Sullivan, 2012; Raineki et al., 2015; Roth & Sullivan, 2005). Our lab uses a form of the latter model termed the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources wherein pup exposures occur outside the home cage with dams placed in a novel environment and given insufficient nesting materials. This results in disrupted maternal care such that adverse behavior directed toward pups (i.e. dragging, dropping, stepping on, roughly handling, or actively avoiding pups) is significantly increased when compared to pups in the home cage or in a control condition where nesting resources are plentiful (Doherty, Forster, & Roth, 2016; Roth, Lubin, Funk, & Sweatt, 2009; Roth, Matt, Chen, & Blaze, 2014).

These different early stress models often produce different behavioral outcomes. For example, offspring of naturally low-licking and grooming dams exhibit significantly increased levels of anxiety-like behavior in the open field test when compared to offspring of naturally high-licking and grooming dams (Caldji et al., 1998). In contrast, adult mice exposed to fragmented maternal care in infancy exhibit no significant behavioral differences in this same test when compared to controls (Rice, et al., 2008). Behavioral outcomes can also differ within the same model, presumably based on variations in model parameters. For example, maternal separation has been shown to both diminish (Stevenson, Spicer, Mason, & Marsden, 2009) and enhance (Toda et al., 2014) conditioned fear in adult male rats (using 6-hour and 3-hour separations, respectively). These variations across and within models indicate that the phenotypic impact of each model (and variation therein) should be examined.

The aim of this study was to characterize phenotypic outcomes in the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources outside the home cage. Our lab has previously identified the impact of these brief and repeated exposures on one realm of behavior, maternal behavior (Roth, et al., 2009), as well as the epigenome in several brain areas of adolescent and adult animals (Blaze, Asok, & Roth, 2015; Blaze & Roth, 2013; Blaze, Scheuing, & Roth, 2013; Roth, et al., 2014). Here we explore the development of several other behavioral domains following exposure to our model.

Methods

All procedures were conducted by the standards and with the approval of the University of Delaware Animal Care and Use Committee.

Subjects and Caregiving Manipulations

Subjects consisted of male and female Long-Evans rat pups bred in-house. Dams were housed in polypropylene cages with wood shavings and kept in a temperature controlled room on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. On postnatal (PN) day 1 (the day after birth) litters were culled to 5–6 males and 5–6 females.

Caregiving manipulations were conducted as previously reported by our lab (Blaze, et al., 2013; Doherty, et al., 2016; Roth, et al., 2009; Roth, et al., 2014). Pups were exposed to one of three conditions (maltreatment, cross-foster, and normal-care) 30 minutes daily for the first seven days of life. Pups in the maltreatment condition were exposed to a novel environment with a lactating dam (matched in diet and postpartum age to the birth mother of the experimental pups) given insufficient nesting resources and no time to habituate to her surroundings. Pups in the cross-foster condition were exposed to a novel environment with a lactating dam (likewise matched in diet and postpartum age) given ample nesting materials and time to habituate to her environment (approximately 1 hour). Pups in the normal-care condition were simply weighed and returned to their biological mother in the home cage. All sessions were recorded and scored by two trained observers who marked each occurrence (in 5-minute time bins) of both nurturing caregiving behaviors (nursing, licking and grooming) and adverse caregiving behaviors (stepping on, dropping, dragging, roughly handling, or actively avoiding pups). An average of the two observer’s scores was then taken for statistical analysis. Audible and ultrasonic (40 kHz) pup vocalizations were also recorded during each session. Two trained individuals scored each audio file and marked the occurrence of vocalizations (in 1-minute time bins). An average of their scores was then taken for statistical analysis. A subset of litter scores was analyzed to ensure reliability between observers (percent of inter-rate reliability was 87% on average).

Following the last exposure on PN7 pups were left undisturbed in the home cage until weaning between PN21–23. At this time they were pair-housed with a same-sex, same-condition littermate until behavioral testing at PN30 or PN90.

Adolescent and Adult Behavioral Testing

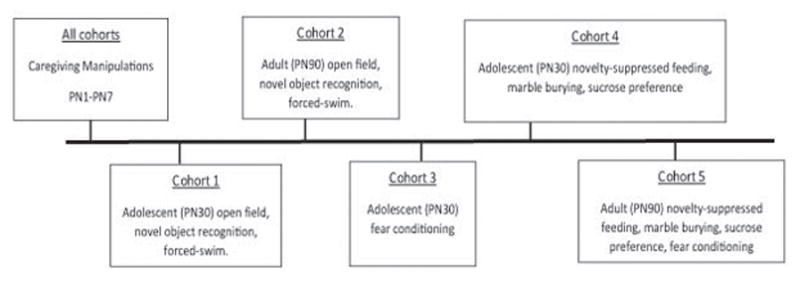

Subjects were tested in adolescence and adulthood (PN30 and PN90, respectively) and no more than 2 males and 2 females from a litter were assigned to an experimental condition in order to avoid litter effects. One cohort was used for adolescent open field, novel object recognition, and forced swim data (tests run in that order on consecutive days). A second cohort was used for adult data on the same tasks. A third cohort was used for adolescent fear conditioning. A fourth cohort was used for adolescent novelty-suppressed feeding, marble burying, and sucrose preference (tests run in that order on consecutive days). A fifth cohort was used for adult novelty-suppressed feeding, marble burying, sucrose preference, and fear conditioning (run in that order on consecutive days). See Figure 1 for cohort layout. Subject numbers for all behavioral tests are provided in corresponding figure legends.

Figure 1.

Figure depicting the tasks assigned to each cohort used as well as the age at which they were assigned.

Sucrose Preference

Subjects were exposed to a 2-day sucrose preference procedure (adapted from (Posillico & Schwarz, 2016)). Rats were exposed during two consecutive sessions to two water bottles, one filled with tap water and the other with 1% sucrose water. Each bottle was weighed (in grams) before and after testing to determine consumption. Orientation of the bottles was switched between testing days to control for place preference. Day 1 was considered a habituation session to the two-bottle choice arrangement. A sucrose preference score was then derived from data obtained on day 2 by dividing the average weight in grams of sucrose consumed by the average weight in grams of total liquid consumed, multiplied by 100.

Forced swim test

Rats were exposed to the habituation phase of the Porsolt forced swim test (adapted from (Castagné, Moser, Roux, & Porsolt, 2011) in which they were placed in ~9 inches of room temperature (~25°C) water in 27 cm diameter × 30 cm height (adolescent) or 29 cm diameter × 48 cm height (adult) buckets for 15 minutes. Rats were then thoroughly dried with a microfiber cloth and placed in a warm cage over a heating pad until dry. Twenty-four hours later, rats were again placed in the forced swim chamber for 5 minutes and time spent immobile (i.e., only making movements necessary to keep head above water) and latency to go immobile were scored by trained observers.

Novelty-suppressed feeding task

Rats were exposed to a novelty-suppressed feeding task (adapted from (Merali, Levac, & Anisman, 2003)). Rats were exposed for ten minutes to a familiar food reward (an almond slice) in an 38 cm diameter × 22 cm height (adolescent) or 84 cm diameter × 36 cm height (adult) novel, open arena. All testing was performed in red light with white noise (approximately 60 dB). Prior to testing day, subjects were familiarized with the almond slice via two home-cage exposures, one in the early morning and one in the late evening. The food reward was presented in the home cage in the same manner in which it was to be encountered in the arena (i.e. with the almond slice placed in the middle of a clear plastic petri dish). All animals began the test from the same point in the arena and latency to consume the food reward was recorded. The arena was cleaned thoroughly with ethanol between each subject.

Marble burying

Rats were exposed to a marble burying task (adapted from (Pandey, Yadav, Mahesh, & Rajkumar, 2009)). Rats were placed in individual polypropylene cages (20 cm x 46 cm x 23 cm) containing 5cm of clean bedding upon which ten clean marbles (15 mm diameter) were placed, evenly spaced throughout the cage. Subjects were then recorded for ten minutes and removed. Buried, partially buried, and unburied marbles were then counted and recorded.

Open field test

Rats were exposed to an open field test (adapted from (Arakawa, 2003)). All testing was performed in red light with white noise (approximately 60 dB). Subjects were handled (picked up and sat on experimenter’s arm for two minutes) for two days prior to testing. On test day, rats were placed in an 38 cm diameter × 22 cm height (adolescent) or 84 cm diameter × 36 cm height (adult) circular open field for 10 minutes. Line crosses and time spent in the center of the field as well as number of entries into the center were video recorded and scored by trained observers. The open field apparatus was cleaned thoroughly with ethanol between each subject.

Fear Conditioning

Fear conditioning, extinction, and retention testing protocols were performed in adolescent (adapted from (Kim, Li, & Richardson, 2010)) and adult (Chang et al., 2009) animals. Fear conditioning was performed in context A and involved three (adolescents) or five (adults) conditioned stimulus (CS)-unconditioned stimulus (US) pairings. The CS was a tone (2 kHz, 10 s, 80 dB) which co-terminated with the US foot shock (1 mA, 1s). Extinction training was conducted 24 hours later in context B and comprised 30 CS-only presentations. Extinction retention testing was conducted in context B (i.e. the extinction training context) 24 hours after extinction training and was comprised of five CS-only presentations. Contexts were made distinct by manipulating sensory cues (changing the floor from metal bars to smooth plastic, covering walls with checkered inserts, and changing the odor from ethanol to vanilla between contexts A and B). After every session, each apparatus was cleaned thoroughly with ethanol on day one or quatricide on day 2 (differed cleaning agents to maintain distinct odors between contexts). All behavioral sessions employed a 120s baseline period and 60s inter-trial intervals (ITI). Cameras located on the ceiling of the boxes recorded behavioral videos, which were scored in real-time for freezing behavior using ANY-maze software (Stoelting Inc.). Freezing during the CS presentation and the following ITI were blocked into one trial and converted into percentages for statistical analyses.

Novel object recognition (NOR)

Rats were exposed to a novel object recognition task (adapted from (Oliveira, Hawk, Abel, & Havekes, 2010)). Following habituation to the chamber, subjects were exposed to two of the same objects (PN30: orange 50 ml conical tubes or 7 cm diameter x 5 cm height yellow measuring cups; PN90: orange 50 ml conical tubes or 2 inch width black binder clips) secured in the open-field chamber (38 cm diameter × 22 cm height for adolescents or 84 cm diameter × 36 cm height for adults) for 15 minutes. Twenty-four hours later subjects were returned to the testing chamber with one of the objects from the previous day and one novel object for 15 minutes. The testing apparatus was thoroughly cleaned with ethanol between subjects. Video was recorded and trained observers scored time spent interacting with each object. These values were then used to obtain an exploration ratio (time spent exploring novel object/time spent exploring both).

Statistical analyses

Two-way ANOVAs and when necessary, Bonferroni post-hoc tests were used to analyze caregiving behaviors (factors: caregiving behavior and infant condition), sucrose preference, marble burying, novelty-suppressed feeding, and open-field performance (factors: infant condition and sex). For fear conditioning analysis, freezing during the CS presentation and the following ITI were blocked into one trial and converted into percentages for statistical analyses. All behavioral data were subjected to an infant condition (normal care, foster care, maltreatment) x sex (male vs. female) x trial (1-n) factor design. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to analyze freezing data. T-tests with Bonferroni corrections were applied when necessary. Finally, as is common for analyzing novel-object recognition performance (Dix & Aggleton, 1999; Ramsaran, Westbrook, & Stanton, 2016), exploration ratios of each group were compared to chance performance (50%) using one-sample t-tests.

Results

Caregiving Manipulations

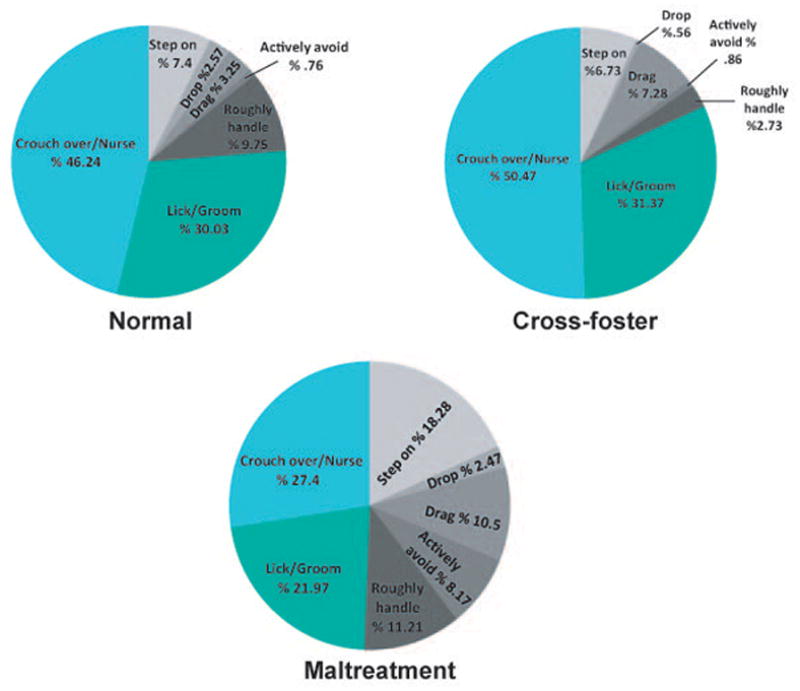

Assessment of caregiving behavior with a two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect of caregiving behavior (F1,98 = 219.8, p<0.001) and a behavior X infant condition interaction (F2,98 = 57.56, p<0.001). Infants exposed to normal- and cross-foster care experienced significantly higher levels of nurturing care and significantly lower levels of adverse care when compared to infants exposed to the maltreatment condition (p’s<0.001). Adverse and nurturing behaviors are illustrated in Figure 2 for each condition. One-way ANOVAs revealed a significant effect of infant condition on the level of hovering/nursing (F2,49 = 10.94, p<0.001), stepping on pups (F2,49 = 21.44, p<0.001), dropping pups (F2,49 = 4.376, p<0.05), dragging pups (F2,49 = 7.941, p<.01), actively avoiding pups (F2,49 = 15.46, p<0.001), and roughly handling pups (F2,49 = 9.023, p<.001). No significant differences in licking/grooming behavior were found between groups (p=0.244). Bonferroni post-hoc tests revealed that when compared to normal and cross-foster care controls, maltreated pups experienced significantly lower levels of hovering/nursing (p’s<0.01) and higher levels of stepping (p’s<0.001) and avoidance (p’s<0.001) during manipulations. Maltreated pups were also dropped significantly more than cross-foster care pups (p=0.0268) and dragged (typically while nipple attached) significantly more than pups in the normal care condition (p=0.0007). Post-hoc analysis also revealed that pups in the cross-foster care condition experienced significantly lower levels of rough handling by the dam during experimental manipulations than both normal-care and maltreated pups (p’s<0.05). Additionally, levels of audible and ultrasonic vocalizations emitted by maltreated pups (see Table 1 for means and statistical comparison) during caregiving manipulations were comparable to those previously reported by our lab (Blaze, et al., 2013; Roth, et al., 2014).

Figure 2.

Distribution of nurturing and adverse behaviors exhibited by dams in each treatment group; n=17–18 dams per group.

Table 1.

Means and statistical values from analyses of audible and ultrasonic vocalizations.

NMC= normal maternal care; CFC=cross-foster care; MAL=maltreatment.

| Pup Vocalizations | F | p | Bonferroni adjusted p | Mean | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Audible | NMC: 39.80 | 3.529 | |||

| 3.375 | 0.0427 | non-significant | CFC: 38.22 | 4.057 | |

| MAL: 50.98 | 3.62 | ||||

|

|

|||||

| NMC: 67.03 | 5.317 | ||||

| Ultrasonic | 5.805 | 0.0055 | NMC vs CFC = 0.0292 | CFC: 46.59 | 5.122 |

| CFC vs MAL = 0.0083 | MAL: 70.53 | 5.65 | |||

Behavior Outcomes

Infant manipulations had no effect on adolescent outcomes in any of the tasks used here to assess behavior (see Table 2 for statistics). For adults however behavioral performance in many of these tasks was altered.

Table 2.

Statistical values from analyses of each adolescent behavioral task.

| PN30 Behavioral Tasks | Interaction | Infant Condition | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sucrose Preference | F2,22=0.7679, p=0.4760 | F2,22=0.1060, p=0.8999 | F1,22=0.1478, p=0.7043 |

|

|

|||

| Forced Swim Test Time Spent Immobile | F2,66=0.1.544, p=0.2212 | F2,66=0.01239, p=0.9877 | F1,66=3.167, p=0.0797 |

|

|

|||

| Forced Swim Test Latency to Immobility | F2,66=1.636, p=0.2024 | F2,66=1.255, p=0.2916 | F1,66=1.303, p=0.2578 |

|

|

|||

| Marble Burying (Buried) | F2,59=0.06443, p=0.9377 | F2,59=0.1860, p=0.8307 | F1,59=0.004005, p=0.9498 |

|

|

|||

| Open-field Test Center Entries | F2,68=0.6691, p=0.5155 | F2,68=1.935, p=0.1523 | F1,68=0.1984, p=0.6574 |

|

|

|||

| Open-field Test Center Time | F2,68=1.531, p=0.2236 | F2,68=0.6686, p=0.5158 | F1,68=0.2594, p=0.6122 |

|

|

|||

| Novelty-suppressed Feeding Task | F2,60=1.291, p=0.2825 | F2,60=2.472, p=0.0929 | F1,60=1.371, p=0.2463 |

|

|

|||

| Normal-care | Cross-foster care | Maltreated | |

|

|

|||

| Novel Object Recognition (versus chance at 0.5) | ♂t=4.750,

p=0.0177 ♀ t=4.266, p=0.0053 |

♂t=8.918,

p=0.0123 ♀t=6.219, p=0.0016 |

♂t=4.694,

p=0.0054 ♀=4.848, p=0.0029 |

|

|

|||

| Fear Behavior | Fear Conditioning | Fear Extinction | Extinction Retention |

|

|

|||

| Sex X Infant Condition | F2,59=2.558, p=0.086 | F2,59=1.612, p=0.208 | F2,59=1.956, p=0.15 |

|

|

|||

| Trial X sex X infant condition | F6,177=0.525, p=0.766 | F30,885=0.788, p=0.706 | F10,295=1.2.83, p=0.246 |

|

|

|||

| Infant Condition | F2,59=1.281, p=0.285 | F2,59=0.059, p=0.943 | F2,59=0.176, p=0.839 |

|

|

|||

| Sex | F1,59=0.004, p=0.949 | F1,59=0.770, p=0.384 | F1,59=0.194, p=0.661 |

|

|

|||

| Trial | F3,177=296.044, p<.001 | F15,885=21.855, p<.001 | F5,295=25.155, p<.001 |

|

|

|||

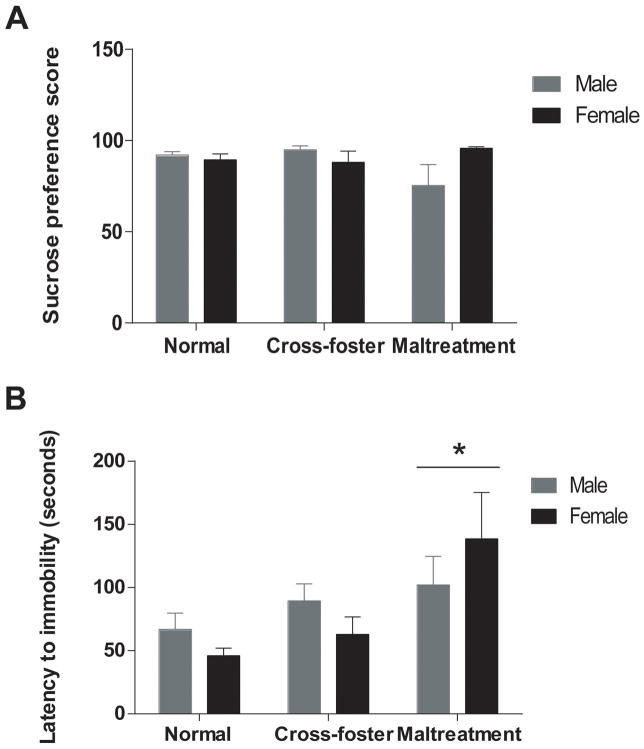

Sucrose preference and forced swim behavior were used to characterize depressive-like adult behaviors (Figure 3). For sucrose preference (Figure 3A), a two-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences between groups on sucrose preference scores for either habituation (day 1) or testing (day 2) (all p’s > 0.05 for sex, caregiving condition, and interaction). While there were no significant effects of condition or sex (or an interaction) on total time spent immobile in the forced swim test, a two-way ANOVA did reveal a significant effect of caregiving condition on latency to go immobile (F(2,54)=4.850, p<0.05, Figure 3B). Bonferroni post-hoc tests indicate a longer latency to immobility in maltreated subjects when compared to their normal-care counterparts (p = 0.0098).

Figure 3.

Sucrose preference scores (A) and latency to immobility during forced swim (B) in adult animals; n=9–12/group; *p<0.05 vs. normal care controls; error bars represent SEM.

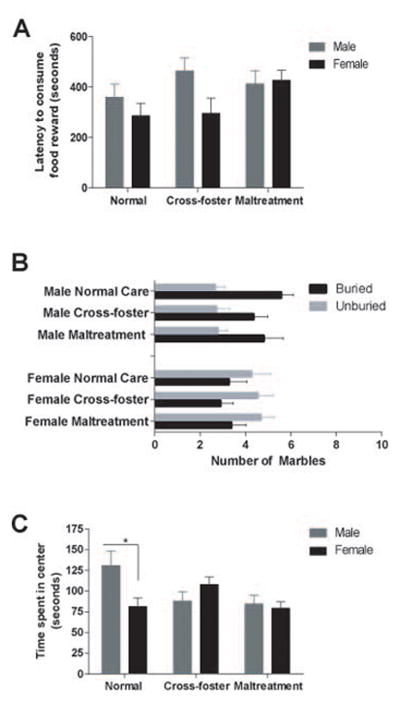

In the realm of anxiety-like behavior, a two-way ANOVA (Figure 4A) revealed no main effect of infant condition (F(2,63)=1.831, p<0.05) or sex (F(2,63)=3.234, p<0.05), nor an interaction (F(2,63)=1.587, p<0.05) on the latency to consume a food reward in the novelty suppressed feeding task. For marble-burying behavior (Figure 3B), two-way ANOVAs revealed no significant differences between infant conditions but did reveal a main effect of sex for buried (F(1, 63) = 9.992, p < 0.01) and unburied (F(1, 62) = 13.15, p < .001) marbles. However, these findings did not survive post-hoc analyses. Finally, a two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between treatment and sex for time spent in the center of the open field (Figure 3C; F(2,55)=4.791, p<0.05). Post-hoc tests revealed that normal care males spent significantly more time in the center compared to normal care females (p = 0.044) and maltreated females (p = 0.03). There was also a significant interaction between caregiving condition and sex for number of entries into the center (F(2,56)=3.435, p<0.05), a finding that did not survive post-hoc analysis. There were no changes in locomotor activity between conditions or sexes (all p’s>0.05; data not shown).

Figure 4.

Latency to consume the food reward in a novelty suppressed feeding task is shown in adult male and female subjects (A). Graph B represents the number of buried and unburied marbles in male and female adult subjects. Graph C illustrates the amount of time in seconds spent in the center of an open field during testing in male and female adult subjects. n=9–13/group; *p<0.05 males vs. females in the normal care condition, error bars represent SEM.

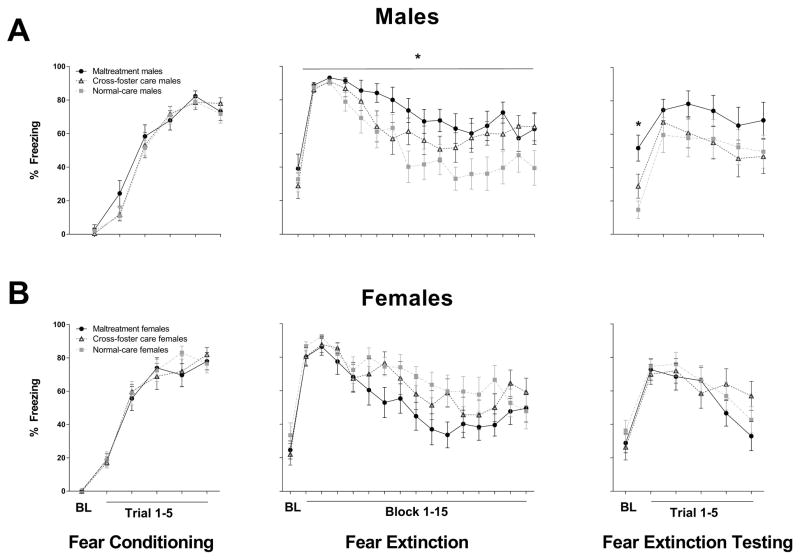

To assess fear-related learning and memory, adult rats were evaluated for fear conditioning, extinction, and retention (Figure 5). ANOVA conducted on fear conditioning training data yielded a main effect for blocked trial (F(5,310) = 333.168, p < .001), indicating that fear conditioning was acquired in all subjects. There were no significant effects of sex or infant caregiver condition during fear conditioning (p’s > .05), suggesting equivalent fear acquisition between both sexes and across all infant caregiver conditions. Analyses of fear extinction training revealed a sex X infant condition interaction (F(2, 63) = 5.724, p = .005). To further examine this interaction, ANOVAs were performed on freezing levels for male and female subjects separately. These analyses revealed a main effect of condition for male subjects (F(2, 31) = 4.1, p = .026). This main effect was mediated by enhanced levels of freezing in male subjects exposed to maltreatment in infancy relative to normal care controls (p = .023). There were no differences in freezing levels across infant conditions in females (p’s > .05). These results indicate that males, but not females, exposed to maltreatment in infancy demonstrate deficits in the acquisition of fear extinction.

Figure 5.

Freezing behavior during fear conditioning, extinction, and extinction retention testing in male (A) and female (B) adult rats; n=10–12 group; *p<0.05 vs normal-care controls; error bars represent SEM. BL = baseline.

This deficit in fear extinction also persisted into fear extinction retention testing. ANOVA performed on fear extinction retention training data yielded a trial X sex X infant condition interaction (F(10, 315) = 1.985, p = .049). Post-hoc analyses indicated that baseline freezing was significantly elevated in maltreated males versus their normal-care control counterparts (p = .002), while females neglected to show different levels of freezing during fear extinction retention testing across infant caregiver conditions (p’s > .05). This effect was male specific; there were no differences in freezing levels in females during the baseline of the fear extinction retention testing session (p’s > .05). These results suggest that second order contextual fear conditioning could be occurring in males with a history of exposure to caregiver maltreatment, as they are acquiring fear to the fear extinction context (i.e. context B) even though the US was never presented in this context. This elevated fear to context B was not present prior to CS exposure in context B (i.e. there was no difference in freezing levels between animals from different infant caregiver conditions during the baseline session of fear extinction).

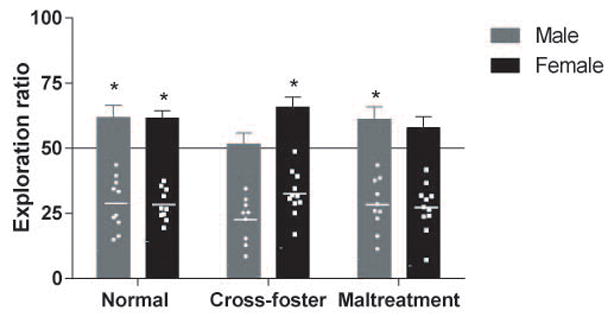

Finally, NOR was used to evaluate recognition memory (Figure 6). During the sample phase (Day 1) both objects were equally explored by all rats (no main effect of infant condition (p=0.7984), sex (p=.2326), nor an interaction (p=0.8397); data not shown). An ANOVA conducted on data from the test phase (Day 2) revealed no main effect of infant condition (p=0.7616) or sex (p=0.2994), nor an interaction (p=0.0970). However, one-sample t-tests (typically used in this task to assess difference from chance, see section on statistical analysis) revealed that normal care (t(10)=4.511, p=0.0011) and cross-foster care females (t(10)=4.082, p=0.0022) could perform significantly above chance in the NOR, whereas maltreated females could not (t(10)=1.867, p=0.0915). For males, the normal care (t(9)=2.434, p=0.0377) and maltreatment (t(9)=2.288, p=0.0480) conditions could perform the task above chance, but the cross-foster group could not (t(8)=0.3434, p=0.7402). The mild impairment detected in maltreated females may be driven by variability (individual data points are provided in Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Exploration ratios in a novel object recognition task in male and female adult subjects along with individual subject points (Means: Normal care females = 61.80; cross-foster care females = 65.79; maltreated females = 57.87; normal care males = 61.79; cross-foster care males = 51.50; maltreated males = 61.12.); n=9–11/group; *p<0.05 vs 50% (chance); error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

Here we characterized behavioral outcomes in the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources, a model of disrupted infant-caregiver interaction. Using a version of this model wherein caregiving manipulations take place outside the home cage, we found group- and sex-specific differences in behavior only at the adult time point. In our assessment of depressive-like behavior we found that maltreated animals exposed to an adverse caregiving environment exhibited a longer latency to immobility in the forced swim test. When assessing anxiety-like behaviors we found that exposure to nurturing or adverse care outside the home cage eliminated the sex-difference seen in normal-care controls in time spent in the center of an open-field arena. Assessment of recognition memory revealed that unlike their normal- and cross-foster care counterparts, maltreated females were unable to perform above chance in a novel-object recognition task.

No deficits were found in males when assessing anxiety-like behaviors with novelty-suppressed feeding and marble burying. However, when assessing performance on a fear conditioning and extinction paradigm, males displayed robust behavioral alterations not found in female subjects. Specifically, males exposed to maltreatment exhibited an extinction deficit such that they were significantly impaired at acquiring extinction when compared to their normal-care counterparts. This deficit persisted into extinction retention testing where they exhibited significantly higher levels of freezing at baseline than normal-care controls. Interestingly, in the novel-object recognition task, cross-foster care males were unable to perform above chance, a deficit that was not found in their normal-care and maltreated counterparts. Though both tasks (novel-object recognition and fear extinction) assess learning and memory and both call on several of the same brain regions, behavioral differences between groups on these tasks may be expected given the considerable element of fear in one task versus the other. Though difficult to surmise, the male cross-foster care deficit on the novel-object recognition task could be related to repeated removal from the home cage and subsequent exposure to a novel environment and dam, an effect that is somehow specific to this condition in which the novel environment is a nurturing one. The fact that this deficit is specific to the cross-foster condition in males will require further investigation to understand which factors are affecting performance in this task. Parameters of the cross-foster condition also appeared to have an effect on open-field performance. The sex difference seen in normal care controls was absent in both the cross-foster and maltreatment groups, suggesting that this effect is not specific to maltreatment.

Depending on one’s interpretation of immobility in the forced swim test, the performance of our maltreated animals could be viewed in one of two ways. Immobility in this task has been interpreted as “behavioral despair” (Porsolt, Bertin, & Jalfre, 1978) in which case the behavior of our maltreated animals could be considered adaptive given that their counterparts succumbed to behavioral despair more quickly. Another interpretation of this behavior is that it’s a coping strategy allowing for energy conservation (West, 1990) in which case our data would suggest a decreased ability to cope in animals exposed to maltreatment. Given that depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors are often comorbid (Grippo, Wu, Hassan, & Carter, 2008; Sartorius, Üstün, Lecrubier, & Wittchen, 1996) and that performance on other depressive (i.e. sucrose preference) and anxiety-like behavior (i.e. marble burying) assessments is on par with normal-care animals, the former explanation may be more likely. Further investigation will be necessary to determine which interpretation, if either, is appropriate. Previous work has also suggested deficits in the forced-swim task to be reflective of an inability to learn the immobility behavior (De Pablo, Parra, Segovia, & Guillamón, 1989). Considering that animals exposed to maltreatment exhibited behavioral deficits on tasks used to assess cognitive performance (i.e. novel-object recognition and fear learning/memory), the possibility that their forced-swim behavior is indicative of cognitive deficits also warrants further investigation.

Given that sucrose preference and forced swim tasks are often used in conjunction to assess depressive-like behavior, the opposing behavioral outcomes on these tasks is curious but not entirely surprising. The lack of difference between groups in sucrose preference may be fitting in the context of some of the forced swim interpretations discussed above. For example, if forced swim differences are interpreted in the light of either adaptability or cognitive deficit, lack of difference in sucrose preference is less puzzling. In addition, it is difficult to interpret the lack of differences on this task in our study given the widely variable results it produces based on factors such as rodent strain and experimental parameters such as timing of test (length of sucrose exposure as well as point of time after stressor), sucrose concentration (Brenes Sáenz, Villagra, & Fornaguera Trías, 2006; Pothion, Bizot, Trovero, & Belzung, 2004; Van Dijken, Mos, van der Heyden, & Tilders, 1992). Indeed, the use of sucrose preference to adequately assess reward responsiveness after stress has been called into question (Forbes, Stewart, Matthews, & Reid, 1996). Overall, a much deeper investigation will be required to parse apart the behavioral outcomes reported here and what translational significance they may have.

Altered extinction behavior has been heavily implicated in anxiety disorders and conditions such as PTSD (Milad & Quirk, 2012), and these behaviors are often precipitated by early-life stress (Binder et al., 2008; Heim & Nemeroff, 2001; Heim et al., 2000; Nugent, Tyrka, Carpenter, & Price, 2011; Yehuda & Charney, 1993). The aberrant fear extinction behavior exhibited by males exposed to adverse caregiving are consistent with these data. The continuation of their aberrant freezing behavior into retention testing (i.e. higher levels of freezing at baseline during extinction retention testing) could be indicative of second-order contextual fear conditioning. Second-order conditioning entails the association of an innocuous stimulus with a conditioned stimulus (Pavlov, 1927; Rizley & Rescorla, 1972) and is associated with PTSD (Michèle Wessa & Herta Flor 2007). This is a poignant behavioral difference in our rats given the association between early life adversity and the development of PTSD following exposure to stressful stimuli later in life (McCranie, Hyer, Boudewyns, & Woods, 1992; Yehuda & Charney, 1993; Zaidi & Foy, 1994).

The lack of any behavioral differences in our adolescent animals is somewhat surprising, especially given that other early-stress paradigms disrupt behavior at this time point (Bath, Manzano-Nieves, & Goodwill, 2016; Llorente et al., 2007; Marco et al., 2013; J. Molet et al., 2016), though the exposure time in these paradigms differs greatly from our own. Considering that stress exposure can lead to adaptive behavioral outcomes in some circumstances (Frankenhuis & de Weerth, 2013) (Bagot et al., 2009; D. L. Champagne et al., 2008; Oomen et al., 2010) it is possible that these brief, adverse exposures elicit compensatory mechanisms in adolescence, a stage where an incredible amount of restructuring takes place in the brain (Paus, 2005; Spear, 2000). For example, differential epigenetic marks (mechanisms heavily linked to behavioral outcomes following early stress) are seen in adolescence versus adulthood following early life stress (Blaze, et al., 2013; Doherty, et al., 2016; Roth, et al., 2014) and reversal of epigenetic signatures after maternal separation stress is known to worsen adolescent behavior outcomes (Levine, Worrell, Zimnisky, & Schmauss, 2012).

The absence of differences at this age point may also have relevance to “sleeper effects”, a phenomenon referred to in the clinical literature wherein children exposed to trauma exhibit no behavioral deficits in the short term but develop significant issues as time goes on (Elder Jr & Rockwell, 1979; Freud & Burlingham, 1943; Wallerstein & Blakeslee, 1989). Data here support this as our rats exhibit behavioral abnormalities in adulthood on the same tests they successfully navigated in adolescence. Hormones may play a significant role in the latency of these behavioral deficits given that affective and stress-related behaviors are known to differ before and after puberty (Angold, Costello, & Worthman, 1998; Gomez, Manalo, & Dallman, 2004; Romeo, Lee, & McEwen, 2005). Along this line of reasoning, the sex differences found here support previous literature linking early adversity with differential biological and/or behavioral outcomes in females and males (Barr et al., 2004; Cirulli et al., 2009; Drury et al., 2012; Imanaka et al., 2008; McCormick, Smythe, Sharma, & Meaney, 1995; Pohl, Olmstead, Wynne-Edwards, Harkness, & Menard, 2007).

Characterization of behavioral phenotypes following early-life stress is critical even between similar models where experimental parameters are varied. For example, work from Regina Sullivan’s lab using the scarcity-adversity model of low nesting resources within the home cage between postnatal days 8 and 12 has found depressive-like phenotypes in adolescent rats (Raineki, et al., 2012). In contrast, we did not find any differences in depressive-like behaviors at this age with our experimental parameters (postnatal days 1 through 7, 30-minute exposures outside of the home cage). The Sullivan lab has also reported increases in the time spent immobile during the forced swim test in adult rats exposed to maltreatment in infancy (Raineki, et al., 2015), findings that are also dissimilar from our own. These data help illustrate the importance of experimental variables like timing and severity of stress as factors in the risk for atypical outcomes and psychopathology.

In summary, the behavioral differences reported here help elucidate the utility of our model for investigating mild but repeated bouts of stress in the context of caregiving and its effect on the development of behavior. Such elucidation provides insight into the effects of stress in development as we can compare these results with those of other early stress models with varying parameters, including intensity and duration of stress. It is also useful in providing avenues for future investigation of the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie behavioral dysfunction evoked by early-life adversity.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was supported by grants from The National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103653) and The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD087509). We thank Amy Forster, Angela Maggio, Vamsi Matta, Sarah Pingar, and Megan Warren for their help with running and scoring all behavior.

References

- Agid O, Shapira B, Zislin J, Ritsner M, Hanin B, Murad H, … Lerer B. Environment and vulnerability to major psychiatric illness: a case control study of early parental loss in major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 1999;4(2):163–172. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman CM. Puberty and depression: the roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28(01):51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700593x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anier K, Malinovskaja K, Pruus K, Aonurm-Helm A, Zharkovsky A, Kalda A. Maternal separation is associated with DNA methylation and behavioural changes in adult rats. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;24(3):459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa H. The effects of isolation rearing on open-field behavior in male rats depends on developmental stages. Developmental Psychobiology. 2003;43(1):11–19. doi: 10.1002/dev.10120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagot RC, van Hasselt FN, Champagne DL, Meaney MJ, Krugers HJ, Joëls M. Maternal care determines rapid effects of stress mediators on synaptic plasticity in adult rat hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2009;92(3):292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr CS, Newman TK, Schwandt M, Shannon C, Dvoskin RL, Lindell SG, … Lesch KP. Sexual dichotomy of an interaction between early adversity and the serotonin transporter gene promoter variant in rhesus macaques. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(33):12358–12363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403763101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath K, Manzano-Nieves G, Goodwill H. Early life stress accelerates behavioral and neural maturation of the hippocampus in male mice. Hormones and Behavior. 2016;82:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, McEwen LM, MacIsaac JL, Francis DD, Kobor MS. Natural variation in maternal care and cross-tissue patterns of oxytocin receptor gene methylation in rats. Hormones and Behavior. 2016;77:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggio F, Pisu M, Garau A, Boero G, Locci V, Mostallino M, … Serra M. Maternal separation attenuates the effect of adolescent social isolation on HPA axis responsiveness in adult rats. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;24(7):1152–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder EB, Bradley RG, Liu W, Epstein MP, Deveau TC, Mercer KB, … Nemeroff CB. Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults. JAMA. 2008;299(11):1291–1305. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaze J, Asok A, Roth T. Long-term effects of early-life caregiving experiences on brain-derived neurotrophic factor histone acetylation in the adult rat mPFC. Stress. 2015;18(6):607–615. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2015.1071790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaze J, Roth T. Exposure to caregiver maltreatment alters expression levels of epigenetic regulators in the medial prefrontal cortex. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 2013;31(8):804–810. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaze J, Scheuing L, Roth T. Differential methylation of genes in the medial prefrontal cortex of developing and adult rats following exposure to maltreatment or nurturing care during infancy. Developmental Neuroscience. 2013;35(4):306–316. doi: 10.1159/000350716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenes Sáenz JC, Villagra OR, Fornaguera Trías J. Factor analysis of Forced Swimming test, Sucrose Preference test and Open Field test on enriched, social and isolated reared rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;169(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldji C, Tannenbaum B, Sharma S, Francis D, Plotsky PM, Meaney MJ. Maternal care during infancy regulates the development of neural systems mediating the expression of fearfulness in the rat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95(9):5335–5340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagné V, Moser P, Roux S, Porsolt RD. Rodent models of depression: forced swim and tail suspension behavioral despair tests in rats and mice. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. 2011;55(8.10A):8.10A.1–8.10A.14. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0810as55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne DL, Bagot RC, van Hasselt F, Ramakers G, Meaney MJ, de Kloet ER, … Krugers H. Maternal care and hippocampal plasticity: evidence for experience-dependent structural plasticity, altered synaptic functioning, and differential responsiveness to glucocorticoids and stress. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28(23):6037–6045. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0526-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Chretien P, Stevenson CW, Zhang TY, Gratton A, Meaney MJ. Variations in nucleus accumbens dopamine associated with individual differences in maternal behavior in the rat. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(17):4113–4123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5322-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Ch, Knapska E, Orsini CA, Rabinak CA, Zimmerman JM, Maren S. Fear extinction in rodents. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. 2009:8.23. 21–28.23. 17. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0823s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(5):541–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli F, Francia N, Branchi I, Antonucci MT, Aloe L, Suomi SJ, Alleva E. Changes in plasma levels of BDNF and NGF reveal a gender-selective vulnerability to early adversity in rhesus macaques. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(2):173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotella E, Mestres Lascano I, Franchioni L, Levin G, Suárez M. Long-term effects of maternal separation on chronic stress response suppressed by amitriptyline treatment. Stress. 2013;16(4):477–481. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2013.775241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pablo JM, Parra A, Segovia S, Guillamón A. Learned immobility explains the behavior of rats in the forced swimming test. Physiology & Behavior. 1989;46(2):229–237. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix SL, Aggleton JP. Extending the spontaneous preference test of recognition: evidence of object-location and object-context recognition. Behavioural Brain Research. 1999;99(2):191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty TS, Forster A, Roth TL. Global and gene-specific DNA methylation alterations in the adolescent amygdala and hippocampus in an animal model of caregiver maltreatment. Behavioural Brain Research. 2016;298:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury SS, Theall K, Gleason MM, Smyke AT, De Vivo I, Wong J, … Nelson CA. Telomere length and early severe social deprivation: linking early adversity and cellular aging. Molecular Psychiatry. 2012;17(7):719–727. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Jr, Rockwell RC. Economic depression and postwar opportunity in men’s lives: A study of life patterns and health. Research in Community and Mental Health. 1979;1:249–303. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes NF, Stewart CA, Matthews K, Reid IC. Chronic mild stress and sucrose consumption: validity as a model of depression. Physiology & Behavior. 1996;60(6):1481–1484. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhuis WE, de Weerth C. Does early-life exposure to stress shape or impair cognition? Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2013;22(5):407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Freud A, Burlingham D. Children and war. New York: Ernst Willard; 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Gilles EE, Schultz L, Baram TZ. Abnormal corticosterone regulation in an immature rat model of continuous chronic stress. Pediatric Neurology. 1996;15(2):114–119. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(96)00153-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez F, Manalo S, Dallman MF. Androgen-sensitive changes in regulation of restraint-induced adrenocorticotropin secretion between early and late puberty in male rats. Endocrinology. 2004;145(1):59–70. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Wu KD, Hassan I, Carter CS. Social isolation in prairie voles induces behaviors relevant to negative affect: toward the development of a rodent model focused on co-occurring depression and anxiety. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25(6):E17–E26. doi: 10.1002/da.20375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Nemeroff CB. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1023–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01157-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, Graham YP, Wilcox M, Bonsall R, … Nemeroff CB. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;284(5):592–597. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.5.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huot RL, Plotsky PM, Lenox RH, McNamara RK. Neonatal maternal separation reduces hippocampal mossy fiber density in adult Long Evans rats. Brain Research. 2002;950(1–2):52–63. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02985-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imanaka A, Morinobu S, Toki S, Yamamoto S, Matsuki A, Kozuru T, Yamawaki S. Neonatal tactile stimulation reverses the effect of neonatal isolation on open-field and anxiety-like behavior, and pain sensitivity in male and female adult Sprague–Dawley rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2008;186(1):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivy AS, Brunson KL, Sandman C, Baram TZ. Dysfunctional nurturing behavior in rat dams with limited access to nesting material: a clinically relevant model for early-life stress. Neuroscience. 2008;154(3):1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Li S, Richardson R. Immunohistochemical analyses of long-term extinction of conditioned fear in adolescent rats. Cerebral Cortex. 2010;21(3):530–538. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic M, Lim S, Gudsnuk K, Champagne FA. Sex-specific and strain-dependent effects of early life adversity on behavioral and epigenetic outcomes. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2013:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine A, Worrell TR, Zimnisky R, Schmauss C. Early life stress triggers sustained changes in histone deacetylase expression and histone H4 modifications that alter responsiveness to adolescent antidepressant treatment. Neurobiology of Disease. 2012;45(1):488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippmann M, Bress A, Nemeroff CB, Plotsky PM, Monteggia LM. Long-term behavioural and molecular alterations associated with maternal separation in rats. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;25(10):3091–3098. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente R, Arranz L, Marco EM, Moreno E, Puerto M, Guaza C, … Viveros M-P. Early maternal deprivation and neonatal single administration with a cannabinoid agonist induce long-term sex-dependent psychoimmunoendocrine effects in adolescent rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32(6):636–650. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EM, Valero M, de la Serna O, Aisa B, Borcel E, Ramirez MJ, Viveros MP. Maternal deprivation effects on brain plasticity and recognition memory in adolescent male and female rats. Neuropharmacology. 2013;68:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick CM, Smythe JW, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Sex-specific effects of prenatal stress on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to stress and brain glucocorticoid receptor density in adult rats. Developmental Brain Research. 1995;84(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)00153-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCranie EW, Hyer LA, Boudewyns PA, Woods MG. Negative parenting behavior, combat exposure, and PTSD symptom severity: Test of a person-event interaction model. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1992;180(7):431–438. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrory E, De Brito SA, Viding E. The link between child abuse and psychopathology: a review of neurobiological and genetic research. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2012;105(4):151–156. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merali Z, Levac C, Anisman H. Validation of a simple, ethologically relevant paradigm for assessing anxiety in mice. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):552–565. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michèle Wessa PD, Herta Flor PD. Failure of extinction of fear responses in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Evidence from second-order conditioning. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(11):1684–1692. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Fear extinction as a model for translational neuroscience: ten years of progress. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63:129–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molet J, Heins K, Zhuo X, Mei Y, Regev L, Baram T, Stern H. Fragmentation and high entropy of neonatal experience predict adolescent emotional outcome. Translational Psychiatry. 2016;6(1):e702. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent NR, Tyrka AR, Carpenter LL, Price LH. Gene–environment interactions: early life stress and risk for depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214(1):175–196. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira AM, Hawk JD, Abel T, Havekes R. Post-training reversible inactivation of the hippocampus enhances novel object recognition memory. Learning & Memory. 2010;17(3):155–160. doi: 10.1101/lm.1625310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oomen CA, Soeters H, Audureau N, Vermunt L, van Hasselt FN, Manders EM, … Krugers H. Severe early life stress hampers spatial learning and neurogenesis, but improves hippocampal synaptic plasticity and emotional learning under high-stress conditions in adulthood. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(19):6635–6645. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0247-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan P, Fleming AS, Lawson D, Jenkins JM, McGowan PO. Within-and between-litter maternal care alter behavior and gene regulation in female offspring. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;128(6):736. doi: 10.1037/bne0000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey DK, Yadav SK, Mahesh R, Rajkumar R. Depression-like and anxiety-like behavioural aftermaths of impact accelerated traumatic brain injury in rats: a model of comorbid depression and anxiety? Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;205(2):436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T. Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(2):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov IP. Conditioned reflexes: An Investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Annals of Neurosciences 2010. 1927;17(3):136–141. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972-7531.1017309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl J, Olmstead MC, Wynne-Edwards KE, Harkness K, Menard JL. Repeated exposure to stress across the childhood-adolescent period alters rats’ anxiety- and depression-like behaviors in adulthood: The importance of stressor type and gender. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2007;121(3):462–474. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.3.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. “Behavioural despair” in rats and mice: strain differences and the effects of imipramine. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1978;51(3):291–294. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90414-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posillico CK, Schwarz JM. An investigation into the effects of antenatal stressors on the postpartum neuroimmune profile and depressive-like behaviors. Behavioural Brain Research. 2016;298(Part B):218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothion S, Bizot JC, Trovero F, Belzung C. Strain differences in sucrose preference and in the consequences of unpredictable chronic mild stress. Behavioural Brain Research. 2004;155(1):135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineki C, Cortés MR, Belnoue L, Sullivan RM. Effects of early-life abuse differ across development: Infant social behavior deficits are followed by adolescent depressive-like behaviors mediated by the amygdala. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32(22):7758–7765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5843-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raineki C, Sarro E, Rincón-Cortés M, Perry R, Boggs J, Holman CJ, … Sullivan RM. Paradoxical neurobehavioral rescue by memories of early-life abuse: The safety signal value of odors learned during abusive attachment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(4):906–914. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsaran AI, Westbrook SR, Stanton ME. Ontogeny of object-in-context recognition in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2016;298:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice CJ, Sandman CA, Lenjavi MR, Baram TZ. A novel mouse model for acute and long-lasting consequences of early life stress. Endocrinology. 2008;149(10):4892–4900. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizley RC, Rescorla RA. Associations in second-order conditioning and sensory preconditioning. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1972;81(1):1. doi: 10.1037/h0033333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo RD, Lee SJ, McEwen BS. Differential stress reactivity in intact and ovariectomized prepubertal and adult female rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2005;80(6):387–393. doi: 10.1159/000084203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T, Lubin F, Funk A, Sweatt J. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(9):760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T, Matt S, Chen K, Blaze J. Bdnf DNA methylation modifications in the hippocampus and amygdala of male and female rats exposed to different caregiving environments outside the homecage. Developmental Psychobiology. 2014;56(8):1755–1763. doi: 10.1002/dev.21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T, Sullivan RM. Memory of early maltreatment: neonatal behavioral and neural correlates of maternal maltreatment within the context of classical conditioning. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57(8):823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarro EC, Sullivan RM, Barr G. Unpredictable neonatal stress enhances adult anxiety and alters amygdala gene expression related to serotonin and GABA. Neuroscience. 2014;258:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorius N, Üstün TB, Lecrubier Y, Wittchen HU. Depression comorbid with anxiety: Results from the WHO study on “Psychological disorders in primary health care”. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;168(Suppl 30):38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa VC, Vital J, Costenla AR, Batalha VL, Sebastião AM, Ribeiro JA, Lopes LV. Maternal separation impairs long term-potentiation in CA1-CA3 synapses and hippocampal-dependent memory in old rats. Neurobiology of Aging. 2014;35(7):1680–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24(4):417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson CW, Spicer CH, Mason R, Marsden CA. Early life programming of fear conditioning and extinction in adult male rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;205(2):505–510. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda H, Boku S, Nakagawa S, Inoue T, Kato A, Takamura N, … Kusumi I. Maternal separation enhances conditioned fear and decreases the mRNA levels of the neurotensin receptor 1 gene with hypermethylation of this gene in the rat amygdala. PloS One. 2014;9(5):e97421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijken HH, Mos J, van der Heyden JA, Tilders FJ. Characterization of stress-induced long-term behavioural changes in rats: evidence in favor of anxiety. Physiology & Behavior. 1992;52(5):945–951. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90375-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein JS, Blakeslee S. Second Chances: Men. Women, and Children a Decade After Divorce. 1989:306. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver IC, Cervoni N, Champagne FA, D’Alessio AC, Sharma S, Seckl JR, … Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7(8):847–854. doi: 10.1038/nn1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AP. Neurobehavioral studies of forced swimming: The role of learning and memory in the forced swim test. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 1990;14(6):863–877. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(90)90073-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda R, Charney DS. Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150:235–239. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi LY, Foy DW. Childhood abuse experiences and combat-related PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1994;7(1):33–42. doi: 10.1007/BF02111910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalosnik M, Pollano A, Trujillo V, Suarez M, Durando P. Effect of maternal separation and chronic stress on hippocampal-dependent memory in young adult rats: Evidence for the match-mismatch hypothesis. Stress. 2014;17(5):445–450. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2014.936005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]