Abstract

Background:

Intracranial metastasis from cervical cancer is a rare occurrence.

Methods:

In this study we describe a case of cervical cancer metastasis to the brain and perform an extensive review of literature from 1956 to 2016, to characterize clearly the clinical presentation, treatment options, molecular markers, targeted therapies, and survival of patients with this condition.

Results:

An elderly woman with history of cervical cancer in remission, presented 2 years later with a right temporo-parietal tumor, which was treated with surgery and subsequent stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to the resection cavity. She then returned 5 months later with a second solitary right lesion; she again underwent surgery and SRS to the resection cavity with no signs of recurrence 6 months later. According to the reviewed literature, the most common clinical presentation included females with median age of 48 years; presenting symptoms such as headache, weakness/hemiplegia/hemiparesis, seizure, and altered mental status (AMS)/confusion; multiple lesions mostly supratentorially located; poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma; and additional recurrences at other sites. The best approach to treatment is a multimodal plan, consisting of SRS or whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT) for solitary brain metastases followed by chemotherapy for systemic disease, surgery and WBRT for solitary brain lesions without systemic disease, and SRS or WBRT followed by chemotherapy for palliative care. The overall prognosis is poor with a mean and median survival time from diagnosis of brain metastasis of 7 and 4.6 months, respectively.

Conclusion:

Future efforts through large prospective randomized trials are warranted to better describe the clinical presentation and identify more effective treatment plans.

Keywords: Brain metastasis, cervical cancer, intracranial metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is one of the most malignant cancers affecting women, second only to breast cancer.[16] Each year in the United States, approximately 12,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer with an estimated 4000 deaths.[6] Cervical cancer typically spreads locally via the lymphatic system to the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes; however, it can metastasize to more distant organs—commonly the lung, liver, bone, and supraclavicular lymph nodes—via the hematogenous pathway.[2,3] Some attribute circulatory patterns for the organ-specific spread, while certain tumor cells are thought to migrate based on attraction to certain surrounding environments—called the “seed and soil” hypothesis; distant spread of cancer is more recently thought of as a multistep process known as the “metastatic cascade.”[41] One study found a 5.3-fold greater risk of death for patients with hematogenous metastasis compared to those with lymphatic metastasis.[25] The 5-year survival for metastatic cervical cancer is only 16.5% compared to 91.5% for localized cervical cancer.[29,48] Early stage or locally advanced cervical cancer is treated with a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy; however, there is no standard treatment for patients with metastatic cervical cancer, and the goal is usually palliative.[29] Median survival of patients with metastatic cervical cancer is only 8–13 months.[29,48]

Brain metastasis from cervical cancer is a rare occurrence. With only approximately 100 cases of reported intracranial metastases of cervical cancer in the literature, proper management of these patients remains unclear.[2,6] Presence of tumor cells in cerebral circulation does not necessarily lead to metastatic disease, it largely depends on the host's immune system, number of tumor emboli, tissue neovascularization, and characteristics of the tumor.[2,3] Metastasis to brain has been postulated to occur after spread to the lungs.[6] This is supported by reports that the lungs are the most common area for metastatic cervical cancer; in addition, this pattern of spread is very typical in other types of systemic cancers, such as lung cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma.[6,21] However, there were some reported cases of patients with intracranial metastases from cervical cancer without lung metastases. We described a case of isolated solitary cervical cancer metastasis to the brain and reviewed the literature to characterize more clearly the clinical presentation, treatment, and prognosis of patients with this condition.

CASE REPORT

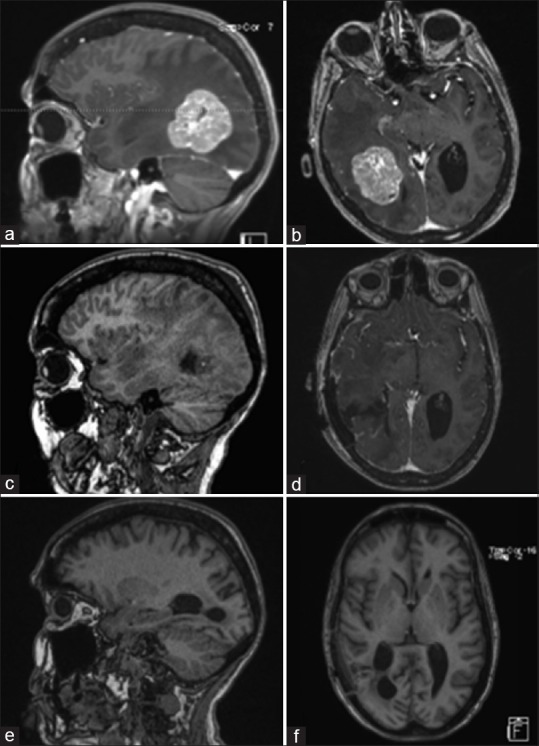

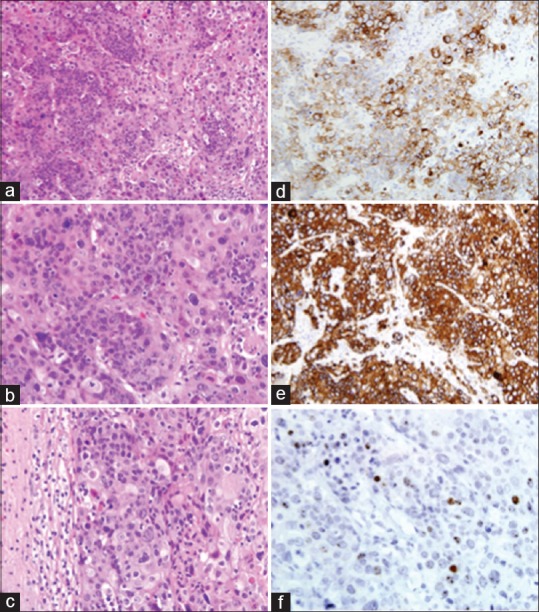

A 75-year-old female with a history of stage IIIB squamous cell cancer of the cervix, which had been treated and in remission for about 2 years, presented in February 2016 with several weeks of decreased coordination and decreased balance with weakness and clumsiness noted especially on her left side in addition to a left facial droop. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her brain showed a solitary 4.6 cm × 3.4 cm × 4.1 cm heterogeneous solid mass at the right temporo-parietal junction with surrounding edema, mass effect, and early uncal herniation suggestive of either a metastasis or high-grade primary lesion [Figure 1a and b]. Computed tomography (CT) of her abdomen and pelvis did not show any primary or metastatic lesion. The patient received dexamethasone, which improved her symptoms, and then underwent surgical resection of the tumor in March 2016. Histopathological examination of the resected tumor revealed an epithelial neoplasm with squamous differentiation and extensive keratinization. The tumor cells displayed considerable anaplasia, and mitoses were numerous [Figure 2a and b]. There was a sharp demarcation between the tumor tissue and the surrounding compressed cerebral parenchyma, which showed gliosis and nerve fiber degeneration [Figure 2c]. Immunohistochemical stains revealed strong positivity for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK5/6 [Figure 2d and e], and also immunopositive for human papilloma virus (HPV), which was confirmed by in situ hybridization for HPV [Figure 2f].

Figure 1.

Pre-operative MRI of brain showing a solitary heterogeneously enhancing solid mass at the right temporal-parietal junction with surrounding edema, mass effect, and early uncal herniation (a and b). Immediate post-operative MRI of brain showing post-operative changes in right temporal-parietal area with gross total resection of the lesion (c and d). MRI of brain seven weeks after surgical resection showing no evidence of tumor progression, significantly improved edema around the resection area, and partially entrapped right occipital horn likely from intraventricular adhesive disease (e and f)

Figure 2.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix, metastatic to the brain: marked anaplasia and extensive keratinization of tumor cells. H and E ×200 (a) and ×400 (b). Note the sharp demarcation between tumor tissue and the surrounding compressed cerebral parenchyma. H and E, ×400 (c). Immunohistochemical stains. Tumor cells are strongly positive for CK7 and CK5/6, ×400 (d and e). In-situ hybridization for HPV (f)

Postoperative MRI [Figure 1c and d] of her brain showed gross total resection of the lesion. The patient experienced no neurological complications postoperatively and was recovering well at the time of discharge. In April 2016, a positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan of the patient's head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed no evidence of recurrent or metastatic disease. The patient had a repeat MRI [Figure 1e and f] of her head in April 2016, which showed no evidence of tumor progression and significantly improved edema around the resection area. Clinically, she was back to independent living without any neurological deficits. She was subsequently treated with stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) to the resection cavity with a dose of 18 Gy to the 50% isodose curve.

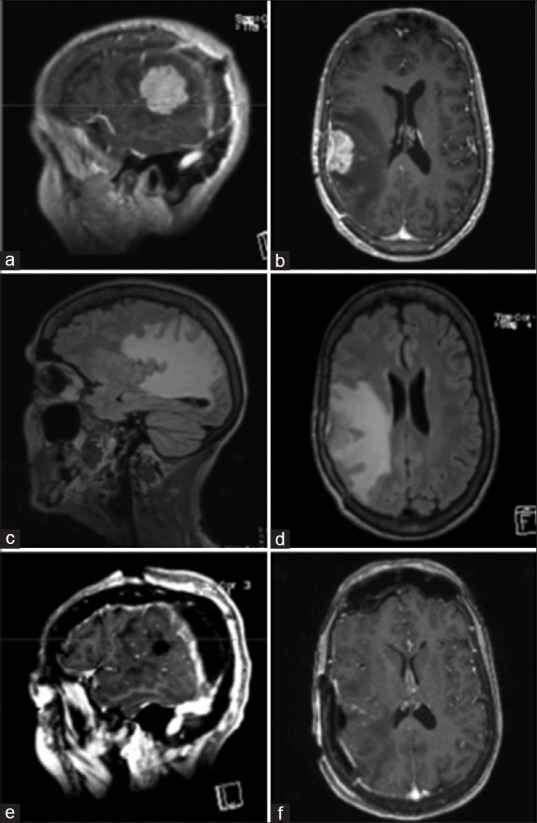

In July 2016, the patient had a left-sided focal clonic seizure and an episode of left-sided weakness. An MRI showed a new single metastatic tumor measuring 2.3 × 3.5 cm2 noted in the right temporo-parietal area with significant surrounding edema within temporal lobe and extending into right parietal and occipital lobes [Figure 3a–d]. Given her excellent performance status and only solitary recurrence, she underwent resection of this second metastatic lesion in July 2016 with a postoperative MRI that showed successful tumor resection with residual edema causing minimal left midline shift [Figure 3e and f], and another treatment of SRS to the resection cavity in August 2016. Another PET/CT scan of her head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis was obtained; it showed small bilateral lung nodules in the right middle lobe and ligula likely of inflammatory origin but still concerning of metastases. Given the size and the imaging characteristics of the lesions, decision was made not to biopsy the lesion and obtaining repeat imaging in 6 months that reported stable nodules with no signs of progression; therefore these lesions were unlikely to be metastases. Serial repeat MRIs showed no evidence of disease progression and clinically she remained independent without any neurological symptoms. The plan for the patient is continued monitoring symptoms along with repeat MRI every 3 months.

Figure 3.

Pre-operative MRI of brain, showing a new enhancing dural based lesion anterior to the prior resection cavity (a-d). Immediate post-operative MRI of brain, demonstrating gross total resection of the lesion (e and f)

DISCUSSION

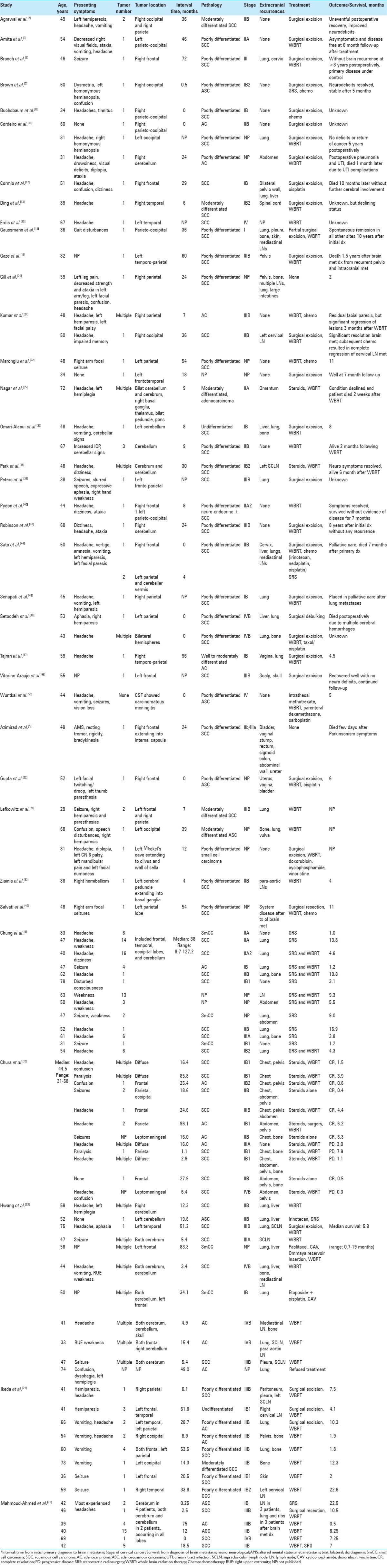

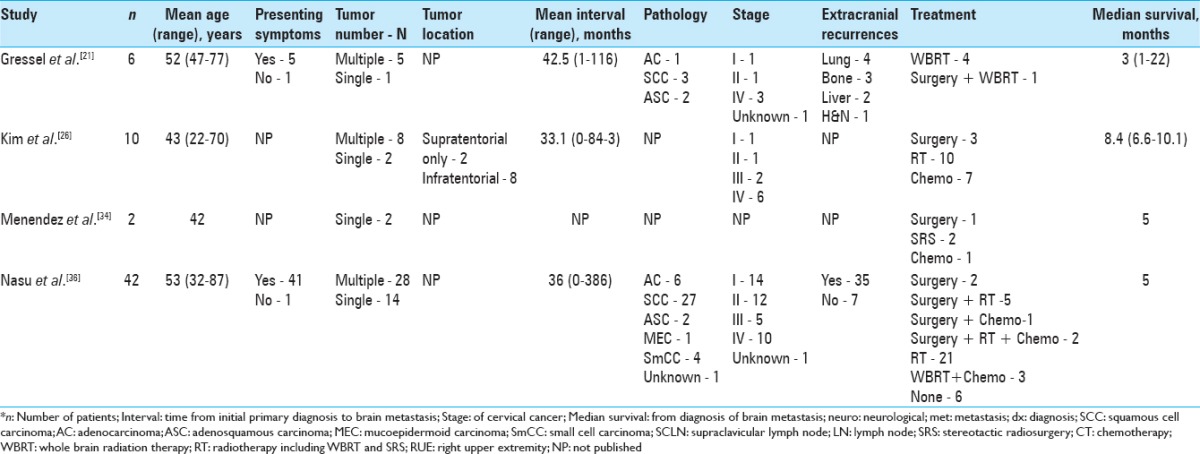

The incidence of cervical cancer metastasis to the brain has been reported as ranging from 0.4% to 2.3%.[14] Recently, there has been an increase in the number of brain metastases from cervical cancer; this is thought to be due to improved treatment of the primary cancer and therefore increased overall survival.[2,3] In our literature review of cervical cancer metastases to the brain, we found 31 case reports describing 39 patients and five case series analyzing 50 patients [Table 1] in addition to four retrospective reviews involving 60 patients [Table 2]. Majority of the patients presented with other systemic metastatic disease along with the brain metastasis. Only a small fraction of patients presented with isolated brain metastasis in the absence of any systemic disease.

Table 1.

Case reports and case series of intracranial metastases from cervical cancer

Table 2.

Retrospective chart reviews of intracranial metastases from cervical cancer

Clinical presentation

The median age of all the patients found in our literature review was 48 years, ranging from 29 to 87 years. Of the interval times and mean interval times reported by the articles from our literature review, the median interval time was 17.2 months. The interval time varied greatly with some patients diagnosed with brain metastasis at the time of their primary cancer diagnosis, while some experienced much longer intervals even up to 8 years. The patient from our case was a 75-year-old female with a 2-year interval time from primary diagnosis to brain metastasis diagnosis.

Of the reported symptoms of the patients from our literature review, the most frequent presenting symptoms included headache (31%), hemiparesis/hemiplegia/weakness (16%), seizure (11%), and altered mental status/confusion (9%). Slightly more than half of these patients (55%) experienced multiple lesions, while slightly less than half (45%) were found to have solitary lesions. Most of the brain metastases were supratentorial (75%) and were found in all the different lobes, and although less frequent, the most common area of infratentorial lesions was in the cerebellum. In our case, the patient presented in February 2016 with left-sided ataxia, weakness, facial droop, and an episode of confusion; she was found to have a solitary lesion located supratentorially in right temporo-parietal lobe. She then presented again in July 2016 after a left-sided focal clonic seizure and an episode of left-sided weakness with findings of another single metastatic lesion in right temporo-parietal lobe.

Mahmoud-Ahmed et al. noted that most brain metastases from cervical cancer are poorly differentiated and of various histologic types.[31] From the patients found in our literature review, the pathology of the tumors was mostly poorly differentiated (77%) and squamous cell carcinoma (68%). Nasu et al. observed that only 35.7% of patients with intracranial metastases from cervical cancer had advanced-stage (III–IV) disease.[36] That observation is supported by the approximately 60% patients found in our literature review which reported to have either stage I or stage II. Recurrence at extracranial sites occurred in majority of the patients reviewed in the literature (87%), and most commonly reported in the lung/chest (39%), bone (16%), and abdomen/pelvis (16%). The patient from our case had stage III squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix with only two solitary brain lesion.

Positive immunohistochemistry for CK7 is frequently seen with squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, which the patient from our case report was found to have from initial brain lesion.[6] Additionally, our patient's initial brain metastasis was determined to be HPV positive, which is not uncommon as over 99% of cervical cancers are positive for high-risk HPV subtypes 16, 18, and 31.[17] HPV has mechanisms of hiding from immune activation, including decreasing the activity of natural killer cells and Langerhans cells, allowing it to maintain a subtle balance between inflammation and tolerance.[52]

Treatment

Similar to intracranial metastasis from other cancers, treatment of intracranial metastasis of cervical carcinoma includes surgery, radiation therapy, SRS, chemotherapy, or a combination of these therapies. Several of the patients from our literature review underwent surgical resection (35%), and many of them received whole brain radiation therapy (WBRT; 48%). However, there were many combinations of different therapies for the treatment plans of these patients, highlighting the lack of standard treatment protocol for this disease process. The most common treatment courses consisted of WBRT alone (17%) and surgical excision plus WBRT (13%); however, the best course of treatment is still not clear at this time with several studies showing benefits of certain multimodal treatment plans. Our literature review shows majority of the younger patients were treated with surgical resection; however, surgical resection in patients greater than 70 years is a rare occurrence. In our case, the patient was treated with surgery, followed by SRS to the resection cavity for both the metastatic lesions. No additional recurrences or new neurological symptoms were noted 6 months following her second tumor resection. We chose to treat with surgical resection in combination with SRS and avoided WBRT because of patients’ excellent performance status.

Surgical resection of cervical cancer metastasis to the brain is typically performed in patients with a solitary tumor or multiple adjacent tumors, patients with critically located or life-threatening metastases, or patients with diagnostic uncertainty.[2] Aggressive treatment either with surgery or SRS followed by adjuvant WBRT and possibly chemotherapy should be strongly considered, especially for young patients, as it has been shown to increase overall survival.[21,23] Postoperative adjuvant radiation therapy has led to increased survival, better neurological status, and lower recurrence of central nervous system lesions than radiation therapy alone.[2,7,11]

Chura et al. examined 12 cases of patients with intracranial metastases from cervical cancer treated with steroids, WBRT, surgery, or a combination of those therapies. The median survival from diagnosis of brain metastasis was 2.3 months (0.3–7.9 months); improved survival was observed in patients who had surgery and patients who underwent SRS with a median survival of 6.2 months vs. 1.3 months for patients treated with only WBRT (P = 0.024). Furthermore, chemotherapy seemed to improve survival with a median of 4.4 months in patients who received chemotherapy after WBRT compared to 0.9 months for patients who did not receive additional treatment after WBRT (P = 0.016).[10]

SRS appears to offer effective local tumor control for gynecologic malignancies with a study by Matsunaga et al.[33] reporting a control rate of 96.4% and response rate of 93%, 6 months after SRS treatment. The decision to use SRS instead of the conventional surgical excision plus adjuvant WBRT for the treatment of intracranial cervical cancer metastases should be determined on an individual basis with consideration of tumor size (<3 cm), number, and location, in addition to clinical status and available technology.[11,14] Chung et al. analyzed 13 patients with brain metastases from cervical cancer—4 patients treated with SRS and 9 patients with both SRS and WBRT. The median survival from diagnosis of brain metastasis was 4.6 months for patients treated with SRS and WBRT compared to only 1.2 months for patients treated with SRS alone (P = 0.012). SRS with WBRT seemed to improve survival; however, patients with poorer prognosis were more likely to be treated with SRS alone instead of combination therapy. Chung et al.[9] suggested that surgical excision or SRS—depending on location, size, and number of lesions—followed by WBRT appears to be an optimal treatment course. They also encouraged the use of SRS as palliative therapy for patients with the goal of providing relief of their symptoms and maintaining a good quality of life; SRS may be the better option for palliative care compared to WBRT, which requires more scheduled sessions in comparison.[9,33]

Chemotherapy plays a significant role in the treatment of cervical cancer, specifically cisplatin; however, its effects on the outcome of intracranial cervical cancer metastases is still not clear but may be used initially in the setting of multiple lesions.[11] Topotecan has specific activity against cervical cancer and is able to cross the blood–brain barrier, which suggests that topotecan may be one of the best chemotherapeutic medications in the treatment of intracranial metastatic cervical cancer.[10,23] Other treatments for unresectable cerebral metastases, such as selective intra-arterial chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, and reversible blood–brain barrier modifiers have not been shown to have a considerable effect.[11]

Prognosis

Although reported incidence of intracranial metastases from cervical cancer is low, autopsy reports have noted that up to 3–10% of cervical cancer patients have brain metastases, which brings to question if and when central nervous system screening should be performed.[6] Brown et al.[7] described a case of brain metastasis after only 2 weeks of being diagnosed with stage IB2 cervical cancer and urged oncology physicians to anticipate this event in order to provide early and comprehensive treatment. However, routine cranial radiological evaluation in the absence of symptoms is not recommended because the incidence of brain metastases from gynecological cancers is quite low, but increased awareness of sentinel symptoms, such as headache, nausea, and vomiting, may help in earlier detection of brain metastasis.[14]

In the early stages of cervical cancer (stage I–IIb), there is a 5-year survival of 65–80% of patients, while there is a 0% 5-year survival with disseminated metastases.[18] Cervical cancer metastasis to the brain carries a poor long-term prognosis with a reported median survival of around 2–8 months[2,7,9] and the majority of patients not surviving beyond 1 year.[6] Several of the case reports did not report overall survival of their patients. Of the patients from this literature review with reported survival times or median survival times, the mean survival time of these patients was 7 months and the median survival time of these patients was 4.6 months, ranging from immediate postoperative death up to 6.5 years. Four patients were reported alive at follow-up after multiple years—3, 5, 8, and 10 years—after their diagnosis of intracranial cervical cancer metastasis. It has been postulated that long-term survival might be due to prolonged therapeutic effects from different genes responsible for metabolizing chemotherapeutic agents, which has been seen in some patients.[18]

The outcome of patients with intracranial metastases from cervical cancer is influenced by the patient's neurological condition, length of clinical history, age, pathological subtype, number of tumors, and comorbidities; good prognostic factors include age <50 years, single brain metastasis, good performance status, and no extracranial metastases.[11,23]

New research is focusing on identifying molecular characteristics of gynecologic tumors in hopes of improving diagnosis, determining prognosis, and guiding treatment according to potentially targetable biomarkers.[14] Zhao et al.[52] discovered decreased mRNA levels of the positive immune factors OX40L/OX40 and Smad3 and increased mRNA levels of the negative immune factors FoxP3 and CCL22/CCR4 in the local microenvironment in tissue samples from patients with cervical cancer compared to normal cervical tissue. Another study found that expression of KIP20A was linked to poorer survival among patients and may contribute to progression of early-stage (I and II) cervical squamous cancer.[51]

Additionally, signaling activation of the protein kinase mTOR, which is involved in protein synthesis, has been noted in both HPV-negative and HPV-positive cervical cancer tissues and cell lines; mTOR inhibitors have also shown to effectively decrease the activity of mTOR along with remarkably decreasing tumor burden.[4] Li et al.[30] also identified increased levels of the oncoprotein HBXIP in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix compared to normal cervical epithelial and that high expression of this protein was related to invasive and metastatic disease with overall lower survival rates. A recent study from 2017 described an array of novel genomic and proteomic features among different subtypes of cervical cancers, identified as keratin-low squamous, keratin-high squamous, and adenocarcinoma-rich as well as HPV-negative, with the hope of future development distinct targeted therapies.[1]

CONCLUSIONS

Cervical cancer metastasis to the brain is an infrequent event. According to our literature review, the median age of diagnosis for these patients was 48 years (29–87 years). The median time interval from primary diagnosis to diagnosis of intracranial metastases was 17.2 months with a wide range spanning from simultaneous diagnosis with primary cervical cancer diagnosis up to 8 years after primary cancer diagnosis. The most common presenting symptoms include headache, weakness/hemiplegia/hemiparesis, seizure, and altered mental status/confusion. The majority of patients were found to have multiple lesions that were mostly supratentorially located. The patients most commonly had poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with additional recurrences at other sites—mainly the chest/lungs, bone, and abdomen/pelvis.

There is no standard treatment for this condition, and a various treatment options and combination of treatment options have been utilized such as surgical excision, WBRT, chemotherapy, and SRS. WBRT with or without surgery has been the most frequently used management. However, treatment should be individualized with the goal of providing symptomatic relief and improving quality of life. Aggressive treatment options should be based on patient's performance status and not age alone. A multimodal treatment plan is highly recommended as the best approach, specifically suggesting the use of SRS or WBRT for solitary brain metastases followed by chemotherapy for systemic disease, the use of surgical resection with WBRT for solitary brain lesions without systemic disease, and the use of SRS or WBRT and steroids followed by chemotherapy for palliative symptomatic relief.[2,9,10,21,23,29,31]

In general, intracranial cervical cancer metastasis carries poor prognosis. Favorable prognostic factors for patients with cervical cancer brain metastases include age <50 years, single brain metastasis, good performance status, and no extracranial metastases.[11,23] Although intracranial metastasis of cervical cancer is a rare phenomenon, the incidence rate is rising, and future efforts to study this disease process through large prospective randomized trials are warranted to better describe the clinical presentation and identify more effective treatment plans in addition to further exploration of specific targeted therapies to aid in the development of improved treatment for these patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Kaleigh Fetcko, Email: kfetcko@iupui.edu.

Dibson D. Gondim, Email: dgondim@iupui.edu.

Jose M. Bonnin, Email: JBonnin@iuhealth.org.

Mahua Dey, Email: mdey@iu.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543:378–84. doi: 10.1038/nature21386. PMID: 28112728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal A, Kumar A, Sinha AK, Kumar M, Pandey SR, Khaniya S. Intracranial metastases from carcinoma of the cervix. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:e154–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amita M, Sudeep G, Rekha W, Yogesh K, Hemant T. Brain metastasis from cervical carcinoma—a case report. Med Gen Med. 2005;7:26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asimomytis A, Karanikou M, Rodolakis A, Vaiopoulou A, Tsetsa P, Creatsas G, et al. mTOR downstream effectors, 4EBP1 and eIF4E, are overexpressed and associated with HPV status in precancerous lesions and carcinomas of the uterine cervix. Oncology Lett. 2016;12:3234–40. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azimirad A, Sarraf Z. Parkinsonism in a recurrent cervical cancer patient: Case report and review of the literature. J Fam Reprod Health. 2013;7:189–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branch BC, Henry J, Vecil GG. Brain metastases from cervical cancer – A short review. Tumori. 2014;100:e171–9. doi: 10.1700/1660.18186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown Iii JV, Epstein HD, Kim R, Micha JP, Rettenmaier MA, Mattison JA, et al. Rapid manifestation of CNS metastatic disease in a cervical carcinoma patient: A case report. Oncology. 2007;73:273–6. doi: 10.1159/000127426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchsbaum HJ, Rice AC. Cerebral metastasis in cervical carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972;114:276–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(72)90075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung SB, Jo KI, Seol HJ, Nam DH, Lee JI. Radiosurgery to palliate symptoms in brain metastases from uterine cervix cancer. Acta Neurochir. 2013;155:399–405. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1576-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chura JC, Shukla K, Argenta PA. Brain metastasis from cervical carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:141–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordeiro JG, Prevedello DM, da Silva Ditzel LF, Pereira CU, Araujo JC. Cerebral metastasis of cervical uterine cancer: Report of three cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64:300–2. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2006000200023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cormio G, Colamaria A, Loverro G, Pierangeli E, Di Vagno G, De Tommasi A, et al. Surgical resection of a cerebral metastasis from cervical cancer: Case report and review of the literature. Tumori. 1999;85:65–7. doi: 10.1177/030089169908500114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding DC, Chu TY. Brain and intramedullary spinal cord metastasis from squamous cell cervical carcinoma. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;49:525–7. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(10)60111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Divine LM, Kizer NT, Hagemann AR, Pittman ME, Chen L, Powell MA, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival of patients with gynecologic malignancies metastatic to the brain. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erdis E. A rare metastatic region of cervix cancer; the brain. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:89–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franco EL, Schlecht NF, Saslow D. The epidemiology of cervical cancer. Cancer J (Sudbury, Mass) 2003;9:348–59. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao G, Smith DI. Human papillomavirus and the development of different cancers. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;150:185–93. doi: 10.1159/000458166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaussmann AB, Imhoff D, Lambrecht E, Menzel C, Mose S. Spontaneous remission of metastases of cancer of the uterine cervix. Onkologie. 2006;29:159–61. doi: 10.1159/000091645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaze MN, Gregor A, Whittle IR, Sellar RJ. Calcified cerebral metastasis from cervical carcinoma. Neuroradiology. 1989;31:291. doi: 10.1007/BF00344367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill TJ, Dammin GJ. A case of epidermoid carcinoma of the cervix uteri with cerebral metastasis. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1959;78:569–71. doi: 10.1002/path.1700780226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gressel GM, Lundsberg LS, Altwerger G, Katchi T, Azodi M, Schwartz PE, et al. Factors predictive of improved survival in patients with brain metastases from gynecologic cancer: A single institution retrospective study of 47 cases and review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:1711–6. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta S, Bandzar S, Atallah H. Atypical presentation of cervical carcinoma with cerebral metastasis. Ochsner J. 2016;16:548–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang JH, Yoo HJ, Lim MC, Seo SS, Kang S, Kim JY, et al. Brain metastasis in patients with uterine cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2013;39:287–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda S, Yamada T, Katsumata N, Hida K, Tanemura K, Tsunematu R, et al. Cerebral metastasis in patients with uterine cervical cancer. Jap J Clin Oncol. 1998;28:27–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/28.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim K, Cho SY, Kim BJ, Kim MH, Choi SC, Ryu SY. The type of metastasis is a prognostic factor in disseminated cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2010;21:186–90. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2010.21.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim YZ, Kwon JH, Lim S. A clinical analysis of brain metastasis in gynecologic cancer: A retrospective multi-institute analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:66–73. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar L, Tanwar RK, Singh SP. Intracranial metastases from carcinoma cervix and review of literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1992;46:391–2. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90239-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lefkowitz D, Asconape J, Biller J. Intracranial metastases from carcinoma of the cervix. Southern Med J. 1983;76:519–21. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198304000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H, Wu X, Cheng X. Advances in diagnosis and treatment of metastatic cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2016;27:e43. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2016.27.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li N, Wang Y, Che S, Yang Y, Piao J, Liu S, et al. HBXIP over expression as an independent biomarker for cervical cancer. Exp Mol Pathol. 2017;102:133–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahmoud-Ahmed AS, Suh JH, Barnett GH, Webster KD, Kennedy AW. Tumor distribution and survival in six patients with brain metastases from cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:196–200. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marongiu A, Salvati M, D’Elia A, Arcella A, Giangaspero F, Esposito V. Single brain metastases from cervical carcinoma: Report of two cases and critical review of the literature. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:937–40. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0861-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsunaga S, Shuto T, Sato M. Gamma knife surgery for metastatic brain tumors from gynecologic cancer. World Neurosurg. 2016;89:455–63. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menendez JY, Bauer DF, Shannon CN, Fiveash J, Markert JM. Stereotactic radiosurgical treatment of brain metastasis of primary tumors that rarely metastasize to the central nervous system. J Neurooncol. 2012;109:513–9. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0916-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagar YS, Shah N, Rawat S, Kataria T. Intracranial metastases from adenocarcinoma of cervix: A case report. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2005;15:561–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2005.15326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasu K, Satoh T, Nishio S, Nagai Y, Ito K, Otsuki T, et al. Clinicopathologic features of brain metastases from gynecologic malignancies: A retrospective study of 139 cases (KCOG-G1001s trial) Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omari-Alaoui HE, Gaye PM, Kebdani T, El Ghazi E, Benjaafar N, Mansouri A, et al. Cerebellous metastases in patients with uterine cervical cancer. Two cases reports and review of the literature. Cancer Radiother. 2003;7:317–20. doi: 10.1016/s1278-3218(03)00085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park SH, Ro DY, Park BJ, Kim YW, Kim TE, Jung JK, et al. Brain metastasis from uterine cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:701–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peters P, Bandi H, Efendy J, Perez-Smith A, Olson S. Rapid growth of cervical cancer metastasis in the brain. J Clin Neurosci. 2010;17:1211–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pyeon SY, Park JY, Ulak R, Seol HJ, Lee JM. Isolated brain metastasis from uterine cervical cancer: A case report and review of literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2015;36:602–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahmathulla G, Toms SA, Weil RJ. The molecular biology of brain metastasis. J Oncol 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/723541. 723541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson JB, Morris M. Cervical carcinoma metastatic to the brain. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:324–6. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salvati M, Caroli E, Orlando ER, Nardone A, Frati A, Innocenzi G, et al. Solitary brain metastases from uterus carcinoma: Report of three cases. J Neurooncol. 2004;66:175–8. doi: 10.1023/b:neon.0000013470.29733.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato Y, Tanaka K, Kobayashi Y, Shibuya H, Nishigaya Y, Momomura M, et al. Uterine cervical cancer with brain metastasis as the initial site of presentation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:1145–8. doi: 10.1111/jog.12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Senapati SN, Samanta DR, Giri SK, Mohanty BK, Nayak CR. Carcinoma cervix with brain metastasis. J Indian Med Assoc. 1998;96:352–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Setoodeh R, Hakam A, Shan Y. Cerebral metastasis of cervical cancer, report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:710–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tajran D, Berek JS. Surgical resection of solitary brain metastasis from cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:368–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2003.13189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Meir H, Kenter GG, Burggraaf J, Kroep JR, Welters MJ, Melief CJ, et al. The need for improvement of the treatment of advanced and metastatic cervical cancer, the rationale for combined chemo-immunotherapy. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2014;14:190–203. doi: 10.2174/18715206113136660372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vitorino-Araujo JL, Veiga JC, Barboza VR, de Souza N, Mayrink D, Nadais RF, et al. Scalp, skull and brain metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix–a rare entity. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27:519–20. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2013.764971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wuntkal R, Maheshwari A, Kerkar RA, Kane SV, Tongaonkar HB. Carcinoma of uterine cervix primarily presenting as carcinomatous meningitis: A case report. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;44:268–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2004.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang W, He W, Shi Y, Gu H, Li M, Liu Z, et al. High expression of KIF20A is associated with poor overall survival and tumor progression in early-stage cervical squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS one. 2016;11:e0167449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao M, Li Y, Wei X, Zhang Q, Jia H, Quan S, et al. Negative immune factors might predominate local tumor immune status and promote carcinogenesis in cervical carcinoma. Virol J. 2017;14:5. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0670-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziainia T, Resnik E. Hemiballismus and brain metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:289–92. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]