Abstract

Background

The efficacy of exercise training in patients with lung cancer after lung resection has not been well established yet. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to investigate the efficiency of exercise training in patients with lung cancer after lung resection.

Methods

Several databases were searched for eligible randomised controlled trials (RCTs). The primary outcome was quality of life, and the secondary outcomes included 6-min walk distance (6MWD), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and postoperative complications (POCs). Weighted mean differences (WMDs) and relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by random-effects model.

Results

Six RCTs involving 438 patients were enrolled in this meta-analysis. The pooled WMDs of the scores were 2.41 (95% CI = −5.20 to 10.02; P = 0.54) and −0.46 (95% CI = −20.52 to 19.61; P = 0.96) for the physical and mental components of the 36-item short-form scale, respectively. The pooled WMDs were 23.50 m (95% CI = −22.04 to 69.03; P = 0.31) for 6MWD and 0.03 L (95% CI = −0.19 to 0.26; P = 0.76) for FEV1. Finally, the pooled RRs were 0.79 (95% CI = 0.41 to 1.53; P = 0.49) for POCs.

Conclusions

Insufficient evidence is available to support the efficacy of exercise training in patients with lung cancer after lung resection. Further studies must confirm our findings and investigate the long-term effects of exercise training on patients with lung cancer following lung resection.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12957-017-1233-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Exercise, Quality of life, Meta-analysis

Background

Cancer is an important public health problem worldwide, and lung cancer accounts for more than one-quarter (27%) of all deaths related to cancer [1]. Lung resection is the most effective treatment approach for patients with lung cancer, especially for those with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [2]. However, patients who underwent lung resection tend to experience deteriorated exercise capacity, lung function and quality of life (QoL); moreover, these patients commonly experience various cancer-related complications, including postoperative complications (POCs), dyspnoea, pain, fatigue and loss of appetite [3–7]. A multidisciplinary approach has been increasingly investigated for appropriate management of patients with lung cancer. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is an effective treatment not only for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) but also for several respiratory conditions, such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, lung transplantation and lung cancer [8–13].

Scholars have proposed that PR programs, including walking [14], exercise training [15], inspiratory muscle training [16], respiratory physiological adaptability training [17] and Tai Chi [18], can improve pulmonary and physical function, decrease the risk of POCs and the length of hospital admission and potentiate human immunity against tumours. These programs can also be used to manage patients with lung cancer [19]. Several published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) [15, 16, 20–22] and non-RCTs [23–25] evaluated the role of PR in patients with lung cancer after lung resection. However, these trials were initially designed to compare different primary endpoints due to different foci; moreover, clinically important endpoints, such as exercise capacity and QoL, have not been adequately investigated due to limited data in each trial. Results of these trials are inconclusive because of the wide variation in sample sizes employed. Thus far, the effect of exercise training on patients with lung cancer after lung resection remains controversial. In the present study, we performed a meta-analysis on available RCTs to investigate the role of exercise training in adult patients following lung cancer surgery.

Methods

Data sources and selection criteria

Several databases including PubMed, Cochrane, CINAHL, EMBASE and PEDro were searched for eligible RCTs up to February 2017. The search strategies for PubMed are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1 and were used for the other databases. No language restriction was implemented. The search was restricted to adult subjects. To ensure data saturation, we manually searched the reference lists of included studies for unpublished studies and reviews to identify any potentially eligible trials.

The available RCTs were selected with the following criteria: (i) population: adult patients with lung cancer who underwent lung resection, (ii) intervention: various forms of exercise trainings, including endurance, resistance, strength, treadmill and walking, (iii) control: usual care or standard postoperative care, (iv) outcomes: the primary outcome was QoL, and the secondary outcomes included 6-min walk distance (6MWD), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and POCs and (v) study design: randomised controlled trial.

Data extraction and outcome measurement

Two authors independently extracted the following data from the studies: first author; publication year; sample size per group (intervention/control); age; protocol of exercise training (e.g. exercise type, time per session, frequency, intensity and duration); outcomes; study designation and Jadad scale. Disagreements were resolved by a third author. In addition, analytical data missing from the original published studies were requested from the respective authors.

The predefined primary outcome was QoL, and the secondary outcomes included 6MWD, FEV1 and POCs. The QoL evaluation scales included the Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) [26], the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [27] and St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) [28]. Considering the limited QoL data, we conducted the meta-analysis of the physical and mental component scores only of the SF-36 scale; high scores indicate better QoL. POCs were defined as X-ray changes reported by the radiologist; POCs include pneumonia, respiratory complications requiring additional ventilatory support and return to high-dependency care and death and transfer to critical care > 72 h after the surgery [15, 16, 20].

Quality and risk-of-bias assessment

The methodological quality was evaluated according to the Jadad scale [29]. In detail, randomisation (0–2 points), blinding (0–2 points) and dropouts and withdrawals (0–1 point) were identified in the scale. A trial with a score ≤ 2 indicates low quality, and that with a score of ≥ 3 indicates high quality [30]. In addition, the risk of bias was assessed by the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool [31]. A third author (GGX) resolved any disagreements regarding classification of study quality components.

Statistical analysis

This meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement [32]. Weighted mean differences (WMDs) and relative risks (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for continuous and dichotomous outcomes were calculated by random-effects model [33]. Heterogeneity was tested using Cochrane’s Q test and I 2 statistic, where I 2 > 50% was classified as significant heterogeneity [34]. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity and investigate the influence of a single study on the overall pooled estimate. Potential publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots. All data and statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.3 (the Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). Finally, a two-sided P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance, and the overall results were compared with the minimum clinically important difference (MCID).

Results

Eligible studies

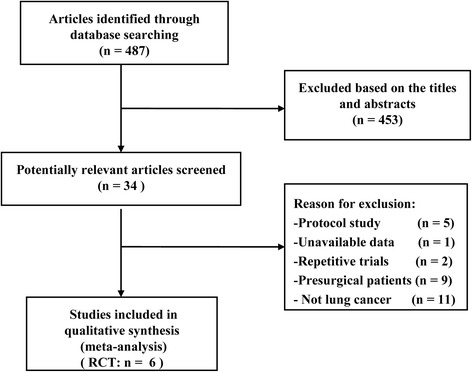

Initially, 487 potential studies were retrieved from the computerised electronic search. Based on titles and abstracts, 453 studies were excluded because they are unrelated to the aims of the present work. Twenty-eight candidate studies were further excluded for various reasons (Fig. 1). Finally, six RCTs were selected for the meta-analysis [15, 16, 20–22, 35]. Only one of these RCTs failed to be included for full-text analysis [35].

Fig. 1.

Search strategy and flow chart (randomised controlled trials; RCTs)

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of the six RCTs, with a total of 438 patients. All RCTs were made available in English and conducted between 2010 and 2015. The sample size of all trials ranged from 49 to 131. Five RCTs [15, 20–22, 35] included patients with NSCLC only [16]. The duration of exercise training ranged from 2 to 20 weeks, and the exercise lasted for 5–60 min per session. Two RCTs [16, 35] did not report the exact exercise duration per session. All of the RCTs included applied different forms and intensities of exercise.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomised controlled trials included in the meta-analysis

| Study/year | Patients no. (I/C) | Cancer type | Age, mean, years (I/C) | Intervention group | Control group | Primary outcome | Secondary outcomes | Study design/Jadad score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of PR | Time/session | Frequency | Intensity | Duration | ||||||||

| Arbane et al., [15] | 51 (26/25) | NSCLC | 65.4/62.6 | Strength and mobility training | 5–10 min | Twice daily | 60–80% MHR | 12 weeks + 5 days | Usual care | 6MWD | POC, QoL, quadriceps strength | RCT/4 |

| Arbane et al., [20] | 131 (64/67) | NSCLC | 67/68 | Hospital plus home exercise | 30 min | Once daily | 60–90% MHR | 4 weeks | Usual care | Physical activity | POC, QoL, quadriceps strength | RCT/4 |

| Brocki et al., [43] | 78 (41/37) | NSCLC | 64/65 | Aerobic exercise + resistance training + dyspnoea management | NA | NA | 60–80% peak work capacity | 12 weeks | Usual care | QoL | 6MWD, FEV1 | RCT/3 |

| Brocki et al., [16] | 68 (34/34) | NSCLC + metastatic tumour + other type | 69.7/70.5 | Inspiratory muscle training | NA | Twice daily | 30% of MIP | 2 weeks | Standard physiotherapy treatment | Inspiratory muscle strength | 6MWD, FEV1, dyspnoea, POC | RCT/4 |

| Edvardsen et al., [22] | 61 (30/31) | NSCLC | 64.4/65.9 | High-intensity endurance and strength training | 60 min | Three times a week | 80–95% MHR | 20 weeks | Standard postoperative care | Peak oxygen uptake | FEV1, QoL, muscular strength and mass | RCT/4 |

| Stigt et al., [21] | 49 (23/26) | NSCLC | 63.6/63.2 | Aerobic (cycling) + resistance | 60 min | Twice weekly | 60–80% peak load | 12 weeks | Usual care | QoL | 6MWD, FEV1, pain | RCT/4 |

I/C intervention/control, NSCLC non-small cell lung cancer; MHR maximum heart rate, 6MWD 6-min walk distance, QoL quality of life, RCT randomised controlled trial, NA not available, FEV 1 the forced expiratory volume in 1 s, MIP maximal inspiratory pressure

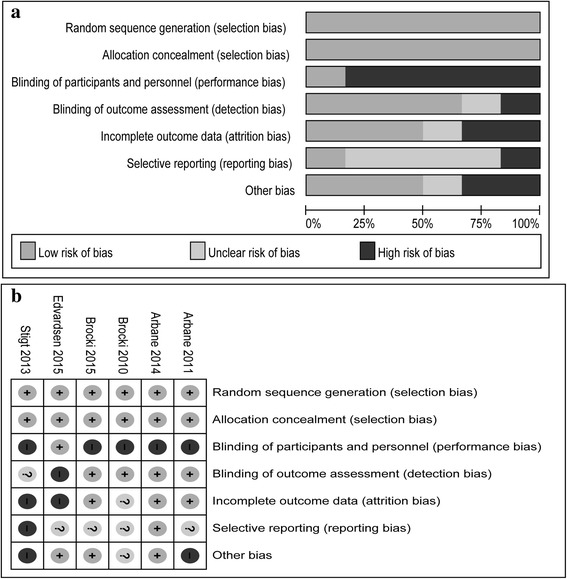

Quality and risk-of-bias assessment

The mean Jadad score of all RCTs was 4.0 (SD = 0.6). The risk-of-bias assessment showed that all RCTs exhibited low risk in terms of random sequence generation and allocation concealment. Table 1 and Fig. 2 show the details of quality and risk-of-bias assessment, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Risk-of-bias assessment: risk-of-bias graph (a) and risk-of-bias summary (b)

Meta-analysis of outcome measures

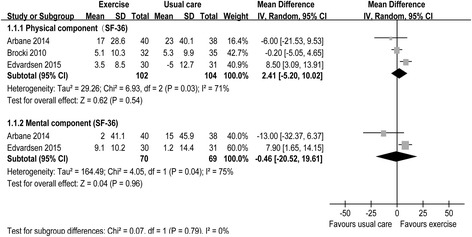

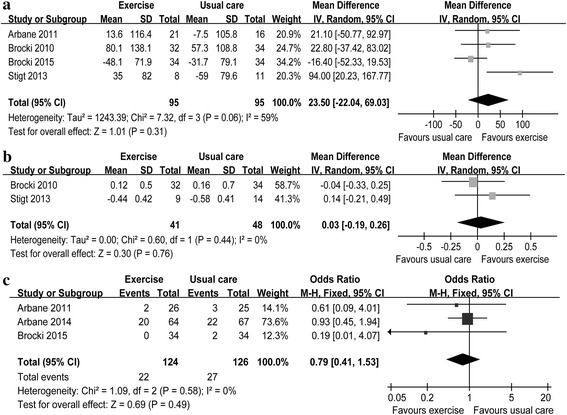

The pooled WMDs of the scores were 2.41 (three RCTs [20, 22, 35]; 95% CI = −5.20 to 10.02; P = 0.54; P for heterogeneity, 0.03; I 2 = 71%) and −0.46 (two RCTs [20, 22]; 95% CI = −20.52 to 19.61; P = 0.96; P for heterogeneity, 0.04; I 2 = 75%) for the physical and mental components of the SF-36 scale, respectively (Fig. 3). The pooled WMDs were 23.50 m (four RCTs [15, 16, 21, 35]; 95% CI = −22.04 to 69.03; P = 0.31; P for heterogeneity, 0.06; I 2 = 59%) for 6MWD (Fig. 4a) and 0.03 L (two RCTs [21, 35]; 95% CI = −0.19 to 0.26; P = 0.76; P for heterogeneity, 0.44; I 2 = 0%) for FEV1 (Fig. 4b). The pooled RRs were 0.79 (three RCTs [15, 16, 20]; 95% CI = 0.41 to 1.53; P = 0.49; P for heterogeneity, 0.58; I 2 = 0%) for POCs (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of QoL, including the physical and mental components of the SF-36 scale

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of secondary outcomes including 6MWD (a), FEV1 (b) and POCs (c)

The physical component QoL exhibited high heterogeneity. We conducted sensitivity analyses to explore the potential source of heterogeneity for the physical component. The exclusion of the study conducted by Edvardsen et al. [22] resolved the heterogeneity but failed to change the results (WMD = −0.71 scores, 95% CI = −5.34 to 3.91; P = 0.76; P for heterogeneity, 0.48; I 2 = 0%). Further exclusion of the other trials did not resolve the heterogeneity and the results [(WMD = 4.06 scores, 95% CI = −4.46 to 12.59; P = 0.35; P for heterogeneity, 0.02; I 2 = 82%) [20], (WMD = 3.15 scores, 95% CI = −10.56 to 16.86; P = 0.65; P for heterogeneity, 0.08; I 2 = 67%) [35], respectively]. Considering that only two RCTs were left, we failed to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the potential source of heterogeneity for the mental component.

Publication bias

Potential publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots when the sample size is small. Additional file 2: Figure S1 shows the types of publication bias for the primary outcome. The results from the analysis of the funnel plots showed no evidence of publication bias.

Discussion

This study conducted comprehensive meta-analysis of available RCTs to evaluate the role of exercise training in adult patients with lung cancer who underwent lung resection. Eligible evidence suggested that exercise training program may be ineffective in improving QoL, exercise capacity and lung function and in decreasing the incidence of POCs. We believe that insufficient evidence is available to support the positive effects of exercise training on patients with lung cancer after lung resection.

Several systematic reviews have been published to describe the effects of exercise intervention on patients with NSCLC following lung resection [36–38]. The present findings show similarity and differences from previous reports. Cavalheri et al. [36, 37] conducted Cochrane systematic reviews of three RCTs with a total of 178 participants. By contrast, our meta-analysis included six RCTs with a total of 438 patients. Considering the limited data on the topic, we combined the latest three RCTs to increase the sample size, strengthen the test performance and produce robust results. In addition, we believe that the analysis of the pooled results may be unsuitable. The final values, instead of the within-group differences (i.e. the difference between baseline and post-intervention in the same group), after administering exercise intervention, were used to pool the outcomes, leading to increased risk of bias and unreliable results. Another narrative review did not conduct a meta-analysis [38]. Therefore, in contrast to aforementioned studies, we combined the three latest RCTs with a large sample size and applied changes from baseline and after intervention for meta-analysis of the outcomes of exercise intervention.

In this study, exercise training did not significantly improve QoL, 6MWD and FEV1 and did not decrease POCs. A significant heterogeneity was found during analysis of QoL. The exclusion of the study conducted by Edvardsen et al. [22] resolved the heterogeneity but failed to change the results. Further exclusion of the other trials did not resolve the heterogeneity and the results. Given the limited data, we could not define the probable sources of heterogeneity for QoL from various clinical characteristics (e.g. different exercise parameters). MCID was defined as the smallest difference considered significant by average patients and a recognised standard for determining the effectiveness of interventions in clinical trials [39]. Comparison of the pooled results included in our study with the MCID showed no statistically significant differences. No MCID is currently available for QoL evaluated by the SF-36 scale and for FEV1 and POCs in patients with lung cancer. Meanwhile, Granger CL [40] published an MCID for 6MWD in lung cancer, but this MCID was used to estimate deterioration rather than improvement. Further studies must be conducted to determine whether the MCID for deterioration is the same as that for improvement. Hence, the MCID reported should not be applied yet for determining improvement in patients with lung cancer. Osoba et al. suggested that changes in the 5–10 scores of EORTC QLQ-C30 represented a MCID in patients with lung cancer [41]. Only three of the RCTs included in the present meta-analysis reported QoL evaluated by the EORTC QLQ-C30 scale [15, 20, 22]. Of these three trials, one reported dyspnoea score [22], and the other trials did not provide related data [20]. Therefore, we could not pool the results for meta-analysis of QoL evaluated by EORTC QLQ-C30. Furthermore, three evaluation methods were used to assess QoL; such methods include SF-36, EORTC QLQ-C30 and SGRQ. The differences in the evaluation methods used complicate the assessment of QoL. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine an appropriate evaluation approach and a consistent evaluation scale for assessment of QoL and define MCID for patients with lung cancer who underwent lung resection.

This work presents valuable information for future clinical research on the effects of exercise training on patients with lung cancer after lung resection. Firstly, exercise programs included various forms, and no ‘standard’ was followed. A suitable form of exercise and appropriate training parameters has not been standardised yet for patients with lung cancer. Therefore, the optimal exercise prescriptions should be individualised based on patient characteristics. Additional studies must focus on establishing suitable forms of exercise for patients with lung cancer who underwent lung resection. Secondly, several studies suggested that Tai Chi may ameliorate the imbalance between humoral and cellular immunity and potentiate human immunity against tumours [18, 42]. Therefore, future research must focus on other exercise forms, such as Tai Chi and Yoga, in addition to general exercise trainings. Thirdly, most studies included in the meta-analysis lack other objective outcome measurements, such as peripheral muscle strength, overall survival and immune function, especially at the cellular and molecular levels. Further research should focus on the above-mentioned endpoints to obtain reliable and convincing evidence with regard to the effect of exercise training on patients with lung cancer who underwent lung resection. Finally, exercise training can benefit patients with COPD. Hence, patients with lung cancer, which is associated with COPD, may also benefit from exercise training. Further large-scale studies must be conducted to investigate the efficiency of exercise training in patients with lung cancer, especially for those with COPD.

Although this meta-analysis was not registered, the study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines and the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration. Our results should be carefully interpreted, considering the following: (i) different exercise forms and parameters are probably the most crucial confounders, which contributed to a certain risk of bias and heterogeneity and influenced the overall results; (ii) few data are available (no more than two to four studies that reported outcomes), thereby influencing the interpretation of the results; and (iii) the primary outcome measurement is inconsistent among all trials, and QoL data were not obtained, resulting in possible selection bias.

Conclusions

Insufficient evidence is available to support the efficacy of exercise training on patients with lung cancer after lung resection. Given the limitations and potential bias of our work, further large-scale robust studies must be conducted to confirm our findings and investigate the long-term effects of exercise training on this group of patients.

Additional files

Table S1. Search strategies for PubMed. (DOCX 11 kb)

Figure S1. Publication bias. (TIFF 840 kb)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program No. 81170007 and No. 81370104) and Fok Ying-Tong Education Foundation of China (No. 131039).

Availability of data and materials

All data are fully available without restriction.

Abbreviations

- 6MWD

6-min walk distance

- CI

Confidence interval

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- EORTC QLQ-C30

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire 30

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- MCID

Minimum clinically important difference

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- POCs

Postoperative complications

- PR

Pulmonary rehabilitation

- QoL

Quality of life

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- RRs

Relative risks

- SF-36

36-item Short Form Health Survey

- SGRQ

The St. George’s respiratory questionnaire

- WMDs

Weighted mean differences

Authors’ contributions

JL and GGX designed the research. JL, NNG, HRK and HY performed the research. HY and PW contributed the new reagents or analytic tools. NNG, HRK and HY analysed the data. JL and NNG wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12957-017-1233-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peddle CJ, Jones LW, Eves ND, Reiman T, Sellar CM, Winton T, et al. Effects of presurgical exercise training on quality of life in patients undergoing lung resection for suspected malignancy: a pilot study. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32:158–165. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181982ca1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amar D, Munoz D, Shi W, Zhang H, Thaler HT. A clinical prediction rule for pulmonary complications after thoracic surgery for primary lung cancer. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1343–1348. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181bf5c99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolliger CT, Jordan P, Soler M, Stulz P, Tamm M, Wyser C, et al. Pulmonary function and exercise capacity after lung resection. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:415–421. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handy JR, Jr, Asaph JW, Skokan L, Reed CE, Koh S, Brooks G, et al. What happens to patients undergoing lung cancer surgery? Outcomes and quality of life before and after surgery. Chest. 2002;122:21–30. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balduyck B, Hendriks J, Lauwers P, Van Schil P. Quality of life evolution after lung cancer surgery: a prospective study in 100 patients. Lung Cancer. 2007;56:423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Win T, Sharples L, Wells FC, Ritchie AJ, Munday H, Laroche CM. Effect of lung cancer surgery on quality of life. Thorax. 2005;60:234–238. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.031872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rochester CL, Fairburn C, Crouch RH. Pulmonary rehabilitation for respiratory disorders other than chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35:369–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendes FA, Goncalves RC, Nunes MP, Saraiva-Romanholo BM, Cukier A, Stelmach R, et al. Effects of aerobic training on psychosocial morbidity and symptoms in patients with asthma: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2010;138:331–337. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klijn PH, Oudshoorn A, van der Ent CK, van der Net J, Kimpen JL, Helders PJ. Effects of anaerobic training in children with cystic fibrosis: a randomized controlled study. Chest. 2004;125:1299–1305. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gloeckl R, Halle M, Kenn K. Interval versus continuous training in lung transplant candidates: a randomized trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31:934–941. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cesario A, Ferri L, Galetta D, Pasqua F, Bonassi S, Clini E, et al. Post-operative respiratory rehabilitation after lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;57:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones LW, Eves ND, Peterson BL, Garst J, Crawford J, West MJ, et al. Safety and feasibility of aerobic training on cardiopulmonary function and quality of life in postsurgical nonsmall cell lung cancer patients: a pilot study. Cancer. 2008;113:3430–3439. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang NW, Lin KC, Lee SC, Chan JY, Lee YH, Wang KY. Effects of an early postoperative walking exercise programme on health status in lung cancer patients recovering from lung lobectomy. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:3391–3402. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arbane G, Tropman D, Jackson D, Garrod R. Evaluation of an early exercise intervention after thoracotomy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), effects on quality of life, muscle strength and exercise tolerance: randomised controlled trial. Lung Cancer. 2011;71:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brocki BC, Andreasen JJ, Langer D, Souza DS, Westerdahl E. Postoperative inspiratory muscle training in addition to breathing exercises and early mobilization improves oxygenation in high-risk patients after lung cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;49(5):1483–1491. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao K, Yu PM, Su JH, He CQ, Liu LX, Zhou YB, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing screening and pre-operative pulmonary rehabilitation reduce postoperative complications and improve fast-track recovery after lung cancer surgery: a study for 342 cases. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6:443–449. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang R, Liu J, Chen P, Yu D. Regular tai chi exercise decreases the percentage of type 2 cytokine-producing cells in postsurgical non-small cell lung cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:E27–E34. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318268f7d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shannon VR. Role of pulmonary rehabilitation in the management of patients with lung cancer. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:334–339. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32833a897d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arbane G, Douiri A, Hart N, Hopkinson NS, Singh S, Speed C, et al. Effect of postoperative physical training on activity after curative surgery for non-small cell lung cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2014;100:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stigt JA, Uil SM, van Riesen SJ, Simons FJ, Denekamp M, Shahin GM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of postthoracotomy pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with resectable lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:214–221. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318279d52a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edvardsen E, Skjonsberg OH, Holme I, Nordsletten L, Borchsenius F, Anderssen SA. High-intensity training following lung cancer surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2015;70:244–250. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim SK, Ahn YH, Yoon JA, Shin MJ, Chang JH, Cho JS, et al. Efficacy of systemic postoperative pulmonary rehabilitation after lung resection surgery. Ann Rehabil Med. 2015;39:366–373. doi: 10.5535/arm.2015.39.3.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavalheri V, Jenkins S, Hill K. Physiotherapy practice patterns for patients undergoing surgery for lung cancer: a survey of hospitals in Australia and New Zealand. Intern Med J. 2013;43:394–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Licker M, Schnyder JM, Frey JG, Diaper J, Cartier V, Inan C, et al. Impact of aerobic exercise capacity and procedure-related factors in lung cancer surgery. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1189–1198. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00069910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones PW. St. George’s respiratory questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2:75–79. doi: 10.1081/COPD-200050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kjaergard LL, Villumsen J, Gluud C. Reported methodologic quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:982–989. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-11-200112040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavalheri V, Tahirah F, Nonoyama M, Jenkins S, Hill K. Exercise training for people following lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer—a Cochrane systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cavalheri V, Tahirah F, Nonoyama M, Jenkins S, Hill K. Exercise training undertaken by people within 12 months of lung resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD009955. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009955.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crandall K, Maguire R, Campbell A, Kearney N. Exercise intervention for patients surgically treated for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a systematic review. Surg Oncol. 2014;23:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Katz JN, Wright JG, Wells G, Boers M, et al. Looking for important change/differences in studies of responsiveness. OMERACT MCID working group. Outcome measures in rheumatology. Minimal clinically important difference. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:400–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Granger CL, Holland AE, Gordon IR, Denehy L. Minimal important difference of the 6-minute walk distance in lung cancer. Chron Respir Dis. 2015;12:146–154. doi: 10.1177/1479972315575715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J, Chen P, Wang R, Yuan Y, Wang X, Li C. Effect of tai chi on mononuclear cell functions in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:3. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0517-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brocki B, Rodkjaer L, Nekrasas V, Due K, Dethlefsen C, Andreasen J. Rehabilitation after lung cancer operation - A randomised controlled study [Abstract]. Annals ERS Annual Congress. 2010:331s.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Search strategies for PubMed. (DOCX 11 kb)

Figure S1. Publication bias. (TIFF 840 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data are fully available without restriction.