Abstract

10.1601/nm.5000 is a rod-shaped facultative anaerobic spore forming bacterium of the genus 10.1601/nm.4857. The defining feature of the species is the ability to produce parasporal crystal inclusion bodies, consisting of δ-endotoxins, encoded by cry-genes. Here we present the complete annotated genome sequence of the nematicidal 10.1601/nm.5000 strain MYBT18246. The genome comprises one 5,867,749 bp chromosome and 11 plasmids which vary in size from 6330 bp to 150,790 bp. The chromosome contains 6092 protein-coding and 150 RNA genes, including 36 rRNA genes. The plasmids encode 997 proteins and 4 t-RNA’s. Analysis of the genome revealed a large number of mobile elements involved in genome plasticity including 11 plasmids and 16 chromosomal prophages. Three different nematicidal toxin genes were identified and classified according to the Cry toxin naming committee as cry13Aa2, cry13Ba1, and cry13Ab1. Strikingly, these genes are located on the chromosome in close proximity to three separate prophages. Moreover, four putative toxin genes of different toxin classes were identified on the plasmids p120510 (Vip-like toxin), p120416 (Cry-like toxin) and p109822 (two Bin-like toxins). A comparative genome analysis of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 with three closely related 10.1601/nm.5000 strains enabled determination of the pan-genome of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246, revealing a large number of singletons, mostly represented by phage genes, morons and cryptic genes.

Keywords: Bacillus thuringiensis, Bacillus cereus sensu lato, Prophages, Parasporal crystal protein, Pan-Core-genome

Introduction

10.1601/nm.5000 is an ubiquitously distributed, rod-shaped, Gram-positive, spore forming, facultative anaerobic bacterium [1, 2]. 10.1601/nm.5000 has been isolated from various ecological niches, including soil, aquatic habitats, phylloplane and insects [3–7]. The defining property of the species is the ability to produce parasporal protein crystals consisting of δ-endotoxins, which are predominantly encoded on plasmids [1, 8, 9]. These proteins are toxic towards a wide spectrum of invertebrates of the orders Lepidoptera , Diptera , Coleoptera , Hymenoptera , Homoptera, Orthoptera , Mallophaga and other species like Gastropoda, mites, protozoa and especially nematodes [7, 10–12]. In addition, 10.1601/nm.5000 produce additional toxins such as Cyt, Vip, and Sip toxins [13]. Cry toxins represent the largest group and can be subdivided into three different homology groups. In total, over 787 different Cry toxins have been identified, each exhibiting toxicity against a specific host organism [14]. It has been shown that 10.1601/nm.5000 strains can produce more than one Cry toxin resulting in a broad host range. As such, 10.1601/nm.5000 has been used widely as a biopesticide in agriculture for several decades [1, 2, 8, 13, 15, 16]. 10.1601/nm.5000 is a member of the genus 10.1601/nm.4857, which are low GC-content, Gram-positive bacteria with a respiratory metabolism and the ability to form heat- and desiccation-resistant endospores [11, 17, 18]. Within this genus, 10.1601/nm.5000 is a member of the 10.1601/nm.4885 sensu lato species group which originally contained seven different species (10.1601/nm.4885, 10.1601/nm.4871 , 10.1601/nm.5000 , 10.1601/nm.4947 , 10.1601/nm.4966 , 10.1601/nm.5007 , 10.1601/nm.23711 [17–25]). Historically, most pathogenic and phenotypic properties were used for strain classification. However, recent publications utilizing genomic criteria suggest that the species group should be extended by species 10.1601/nm.24560 [26, 27]. Moreover, the three proposed species “ 10.1601/nm.27585”[28], “10.1601/nm.27575”[29] and “ 10.1601/nm.26046” [30] have been isolated and effectively published. However, these names had not yet appeared on a Validation List at the time of pulbication [31]. Due to the very close phylogenetic relationships, it has also been proposed to assign the eleven species to a single extended Bcsl species [32, 33]. The genome of Bcsl-members contains a highly conserved chromosome with regard to gene content, sequence similarity and genome synteny, while variation can be observed within mobile genomic elements such as prophages, insertion elements, transposons, and plasmids [34]. Due to the significance of Bcsl group members in human health, the food industry and agriculture, resolving the phylogeny is of great importance. Because of the highly conserved 16S rRNA-genes, the classical 16S phylogeny of Bcsl strains is inconclusive. Thus, a combination of 16S and a seven gene multi-locus sequence typing scheme have been used to establish taxonomic relationships within species of the Bcsl-group [35, 36]. Comparative genomics of the cry-gene loci has revealed remarkable proximity to elements of genome plasticity such as plasmids, transposons, insertion elements and prophages [2, 37–39]. The activity of these mobile elements has resulted in a magnitude of highly diverse plasmid sizes through rearrangements such as deletions and insertions, as well as migration of cry-genes into the bacterial chromosome [40]. The worldwide distribution of 10.1601/nm.5000 and its capacity to adapt to a diverse spectrum of invertebrate hosts is explained by the formation of spores and a remarkable variability in crystal protein families [13]. This toxin arsenal, especially the copy number of individual toxin genes, can be shaped by reciprocal co-adaptation with a nematode host, as previously demonstrated using controlled evolution experiments in the laboratory [41, 42]. The 10.1601/nm.5000 strain MYBT18246 described herein and its host Caenorhabditis elegans have been selected as a model system for such co-evolution experiments [41]. One aim of this sequencing project was to provide a high-quality reference genome sequence for the original 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 in order to obtain a detailed phylogeny and shed light on the evolution of this microparasite, with a particular focus on the presence of virulence factors, elements of genome plasticity and host adaptation factors. Here we present the genome of the nematicidal 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 and its comparative analysis to the three closest relatives identified by MLST phylogeny.

Organism information

Classification and features

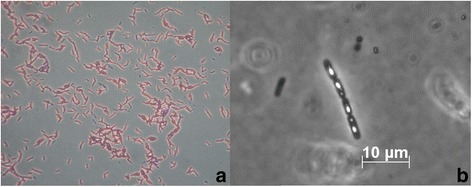

10.1601/nm.5000 belongs to the genus 10.1601/nm.4857 and has been isolated in the end of the nineteenth century [17, 20] and used as a biocontrol agent for several decades [7, 18, 21]. The strain 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 is a Gram-positive, rod-shaped and spore forming bacterium (Fig.1a), as most 10.1601/nm.5000 [7]. 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 was isolated in the Schulenburg lab by AS from a mixture of genotypes present in the strain 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DNRRL+B-18246, originally provided by the Agricultural Research Service Patent Culture Collection (United States Department of Agriculture, Peoria, IL, USA) [43–45]. As a member of the species 10.1601/nm.5000, 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 is facultative anaerobe, motile and is able to produce parasporal crystal toxins, which is the characteristic feature of this species [2]. Growth occurred at temperatures ranging from 10 to 48 °C and optimal growth was monitored at mesophil temperatures ranging from 28 to 37 °C [46]. The pH range of 10.1601/nm.5000 strains varies from pH 4.9 to 8.0, with the optimum documented as pH 7 [47, 48]. Strain 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 exhibits flat, opaque colonies with undulate, curled margins and produced crystals during the stationary phase (Fig. 1a-b). Characteristic features of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 are listed in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Microscopic characteristics of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246. a Light microscope analysis of Gram stained 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 cells (40×). b Phase contrast microscope analysis of sporulated and Cry-toxin producing cells of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 (40×)

Table 1.

Classification and general features of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 [54]

| MIGS ID | Property | Term | Evidence codea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Domain Bacteria | TAS [86] | |

| Phylum 10.1601/nm.3874 | TAS [47] | ||

| Class 10.1601/nm.4854 | TAS [87, 88] | ||

| Order 10.1601/nm.4855 | TAS [18, 89] | ||

| Family 10.1601/nm.4856 | TAS [18, 90] | ||

| Genus 10.1601/nm.4857 | TAS [17, 18] | ||

| Species 10.1601/nm.5000 | TAS [46] | ||

| Strain MYBT18246 | IDA | ||

| Gram stain | positive | IDA | |

| Cell shape | rod-shaped | IDA | |

| Motility | Motile | TAS [46] | |

| Sporulation | Spore-forming | IDA | |

| Temperature range | 10–48 °C | TAS [46] | |

| Optimum temperature | 28–37 °C | TAS [46] | |

| pH range; Optimum | 4.9–8.0; 7.0 | TAS [47, 48] | |

| Carbon source | Organic carbon source | NAS | |

| MIGS-6 | Habitat | Worldwide | TAS [7] |

| MIGS-6.3 | Salinity | Salt tolerant | TAS [7] |

| MIGS-22 | Oxygen requirement | Aerobic, facultative anaerobic | TAS [11] |

| MIGS-15 | Biotic relationship | Free-living, microparasite of C. elegans | TAS [41] |

| MIGS-14 | Pathogenicity | Nematode pathogen | TAS [41] |

| MIGS-4 | Geographic location | not reported | |

| MIGS-5 | Sample collection | not reported | |

| MIGS-4.1 | Latitude | unreported | |

| MIGS-4.2 | Longitude | unreported | |

| MIGS-4.4 | Altitude | unreported |

aEvidence codes - IDA: Inferred from Direct Assay; TAS: Traceable Author Statement (i.e., a direct report exists in the literature); NAS: Non-traceable Author Statement (i.e., not directly observed for the living, isolated sample, but based on a generally accepted property for the species, or anecdotal evidence). These evidence codes are from the Gene Ontology project

Extended feature descriptions

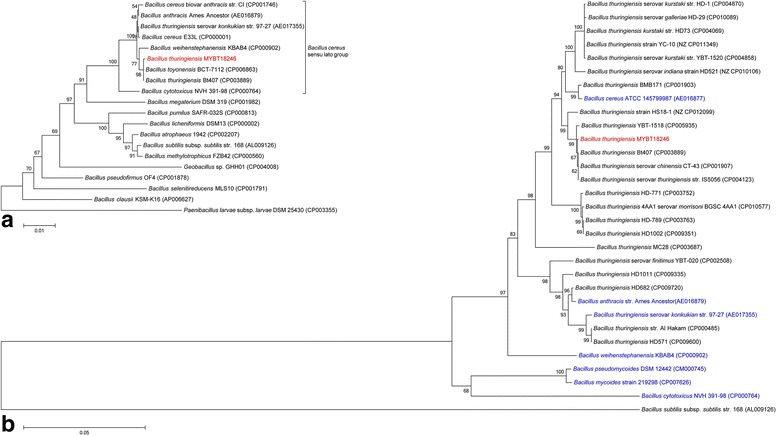

The cell size of 10.1601/nm.5000 can vary from 0.5 × 1.2 μm - 2.5 × 10 μm [11]. Categorization into the group of Gram-positive organisms was confirmed by Gram staining, as shown in Fig. 1a. In Fig. 1b the production of Cry toxins can be observed. These toxins accumulate during the sporulation phase next to the endospore and build phase-bright inclusions [7]. 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 exhibited 99% 16S rRNA sequence identity to other published Bcsl-members [49]. As a result of the high sequence similarity, a phylogenetic differentiation of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 based on 16S phylogenetic differentiation of Bcsl group members is impossible (Fig. 2a). As an alternative, 23 10.1601/nm.5000 strains, and a representative of each of the Bcsl group species were chosen for phylogenetic analysis using multi-locus sequence typing as previously developed by Priest [36] (Fig. 2b). 10.1601/nm.4858 str. 168 was selected as an outgroup to root the tree [17, 18]. The phylogenies were generated using the Neighbor-Joining method [50] and evolutionary distances were computed by the Maximum Composite Likelihood method [51]. In total, 217 MLST gene sequences were compared with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted in MEGA7 [52]. All used reference sequences were retrieved from GenBank hosted at NCBI.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree highlighting the taxonomic relation of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 (red) based on a) 16rDNA amplicon within the 10.1601/nm.4857 clade b) Multi-locus sequence typing within the 10.1601/nm.4885 sensu lato species group. GenBank accession numbers are given in parentheses. Comparison includes strains of the 10.1601/nm.4854 clade or Bcsl group members (blue). 10.1601/nm.5141 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DDSM+25430 or 10.1601/nm.4858 str. 168 has been used as outlier to root the tree. Sequences were aligned using ClustalW 1.6 [91, 92]. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the Neighbor-Joining method [50] and evolutionary distances were computed by the Maximum Composite Likelihood method [51] within MEGA7.0 [52]. Numbers at the nodes are bootstrap values calculated from 1000 replicates

Genome sequencing information

Genome project history

10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 was used in a co-evolution study with a Caenorhabditis elegans host. The original strain MYBT18246 was selected for sequencing in order to generate a reliable reference sequence for subsequent experiments [41, 42]. The genome sequence was analyzed to identify virulence factors and fitness factors contributing to the efficient infection of C. elegans. Additionally, the phylogenetic position of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 in the Bcsl group was determined [41]. The complete genome sequence has been deposited in GenBank with the accession numbers (CP015350-CP015361) and in the integrated Microbial Genomes database with the Taxon ID 2671180122 [53]. A summary of the project information and its association with MIGS version 2.0 compliance [54] is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Project information

| MIGS ID | Property | Term |

|---|---|---|

| MIGS 31 | Finishing quality | Complete |

| MIGS-28 | Libraries used | Two genomic libraries: 454 pyrosequencing shotgun library, PacBio library |

| MIGS 29 | Sequencing platforms | 454 GS FLX system, PacBioRSII |

| MIGS 31.2 | Fold coverage | 18 × 454; 50 × PacBio |

| MIGS 30 | Assemblers | Newbler 2.8; HGAP v2.3.0 |

| MIGS 32 | Gene calling method | Prodigal 2.6 |

| Locus Tag | BT246 | |

| Genbank ID | CP015350-CP015361 | |

| GenBank Date of Release | 2016–07-15 | |

| GOLD ID | Gp0020852 | |

| BIOPROJECT | PRJNA290307 | |

| MIGS 13 | Source Material Identifier | Department of Evolutionary Ecology and Genetics, CAU, Kiel |

| Project relevance | Evolution |

Growth conditions and genomic DNA preparation

Genomic DNA was isolated from 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for 454 pyrosequencing [55] and the Genomic-Tip 100/G Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for Single Molecule real-time sequencing [56] according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For SMRT-sequencing the procedure and Checklist: Greater than 10 kb Template Preparation Using AmPure PB Beads was used and blunt end ligation was applied overnight. Whole-genome sequencing was performed using a 454 GS-FLX system (Titanium GS70 chemistry; Roche Life Science, Mannheim, Germany) and on one SMRT Cell on the PacBio RSII system using P6-chemistry (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA).

Genome sequencing and assembly

A summary of the project information can be found in Table 2. 454-pyrosequencing was carried out at the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology in Kiel, Germany and SMRT-sequencing at the DSMZ Braunschweig. First, approximately 331,000,454-reads with an average length of 600 bp were assembled using the Newbler 2.8 de novo assembler (Roche Diagnostics), resulting in 729 contigs with a coverage of 18 x. Repeats were resolved and gaps between contigs were closed using PCR with Sanger sequencing of the products with BigDye 3.0 chemistry and an 10.1601/strainfinder?urlappend=%3Fid%3DABI+3730XL capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Life Technology GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany). Manually editing in Gap4 (version 4.11) software of the Staden package [57] was performed to improve the sequence quality. For final gap closure PacBio sequencing was used. A total of 27,870 PacBio reads with a mean length of 14,053 bp were assembled using HGAP 2.0 [58], resulting in a coverage of 50 x, with further analysis using SMRT Portal (v2.3.0) [59]. Finally, both assemblies were combined, resulting in 12 contigs including a closed circular chromosome sequence of 5,867,749 bp. Eight additional contigs exhibited overlapping ends and were circularized to plasmid sequences ranging from 6.3 kb to 150 kb (Table 3). The assembly was checked for coverage drop downs and extremes of disparities including GC, AT, RY, and MK. Moreover, we determined the origin of replication of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 by comparative analysis with OriC of eight other 10.1601/nm.5000 strains available in DoriC [60, 61]. These strains varied in chromosome size from 5.2 Mb to 5.8 Mb but all shared a similar GC-content of 35%. In total, including 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246, two OriC regions were identified using the ORF-Finder [62]. One region was highly conserved with regard to OriC length (178/179 nt), OriC AT content (~0.69) and number of DnaA boxes (4). The second region varied in OriC length (564–767 nt) and OriC AT content (~0.67–0.7), but all had the same number of DnaA boxes (9). 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 showed the highest OriC similarities with both OriC regions of 10.1601/nm.5000 Bt407.

Table 3.

Summary of genome: one chromosome and 11 plasmids

| Label | Size (Mb) | Topology | INSDC identifier | RefSeq ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | 5.8 | Circular | CP015350 | NZ_CP015350.1 |

| Plasmid 1 | 0.151 | Circular | CP015351 | NZ_CP015351.1 |

| Plasmid 2 | 0.142 | Circular | CP015352 | NZ_CP015352.1 |

| Plasmid 3 | 0.121 | Circular | CP015353 | NZ_CP015353.1 |

| Plasmid 4 | 0.120 | Circular | CP015354 | NZ_CP015354.1 |

| Plasmid 5 | 0.110 | Circular | CP015355 | NZ_CP015355.1 |

| Plasmid 6 | 0.101 | Circular | CP015356 | NZ_CP015356.1 |

| Plasmid 7 | 0.055 | Linear | CP015357 | NZ_CP015357.1 |

| Plasmid 8 | 0.047 | Circular | CP015358 | NZ_CP015358.1 |

| Plasmid 9 | 0.017 | Linear | CP015359 | NZ_CP015359.1 |

| Plasmid 10 | 0.014 | Linear | CP015360 | NZ_CP015360.1 |

| Plasmid 11 | 0.006 | Circular | CP015361 | NZ_CP015361.1 |

Genome annotation

Annotation was performed with Prokka v1.9 [63] using the manually curated 10.1601/nm.5000 strain Bt407 [64] as a species reference and a comprehensive toxin protein database (including Cry, Cyt, Vip, and Sip toxins) as feature references. The Prokka pipeline was applied using prodigal for gene calling [65]. RNAmmer 1.2 [66] and Aragorn [67] were used for rRNA gene and t-RNA identification, respectively. Additionally, signal leader peptides were identified with SignalP 4.0 [68] and non-coding RNAs with an Infernal 1.1 search against the Rfam database [69]. Annotation of cry toxin genes were manually corrected and named according to the standards of the Cry toxin nomenclature by Crickmore [70]. Identified toxins were deposited at the 10.1601/nm.5000 Toxin nomenclature database [14].

Genome properties

The genome of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 consists of 12 replicons with a circular chromosome of 5,867,749 bp (Table 3). The GC content of the chromosome is 35% and the GC content of the plasmids ranges from 32 to 37%. The total number of protein coding genes is 7089 with 6092 genes on the chromosome and 997 genes on the plasmids. The genome harbors 12 rRNA clusters, 111 t-RNA genes, 5274 predicted protein-coding genes with assigned function and 1815 genes encoding proteins with unknown function (Table 4). All gene products have been assigned to COGs (Table 5). The genome sequence of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 is available in GenBank (CP015350 for the chromosome and CP015351 - CP015361 for the plasmids).

Table 4.

Genome statistics

| Attribute | Value | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 6,752,488 | 100 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 5,623,665 | 83.28 |

| DNA G + C (bp) | 2,389,665 | 35.39 |

| DNA scaffolds | 12 | 100 |

| Total genes | 7239 | 100 |

| Protein coding genes | 7089 | 97.9 |

| RNA genes | 151 | 2.09 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 2694 | 37.22 |

| Genes with function prediction | 5274 | 72.86 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 4662 | 64.40 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 5503 | 76.02 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 500 | 6.91 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1863 | 25.74 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 0 |

Table 5.

Number of protein encoding genes associated with general COG functional categories

| Code | Value | % | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| J | 226 | 3.19 | Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| A | 0 | 0 | RNA processing and modification |

| K | 487 | 6.87 | Transcription |

| L | 625 | 8.82 | Replication, recombination and repair |

| B | 1 | 0.01 | Chromatin structure and dynamics |

| D | 59 | 0.83 | Cell cycle control, Cell division, chromosome partitioning |

| V | 141 | 1.99 | Defense mechanisms |

| T | 218 | 3.08 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| M | 270 | 3.81 | Cell wall/membrane biogenesis |

| N | 64 | 0.90 | Cell motility |

| U | 79 | 1.12 | Intracellular trafficking and secretion |

| O | 121 | 1.71 | Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones |

| C | 214 | 3.02 | Energy production and conversion |

| G | 263 | 3.71 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| E | 420 | 5.93 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| F | 128 | 1.81 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| H | 177 | 2.50 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| I | 129 | 1.82 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| P | 243 | 3.43 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| Q | 83 | 1.17 | Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism |

| R | 653 | 9.22 | General function prediction only |

| S | 505 | 7.13 | Function unknown |

| - | 1978 | 27.9 | Not in COGs |

aThe total number is based on the total number of protein coding genes in the genome

Insights from the genome sequence

To investigate the phylogeny of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 two approaches were used. First, nineteen 10.1601/nm.4857 strains were chosen for 16S rRNA analysis within the 10.1601/nm.4857 clade (Fig. 2a). The 16S rRNA phylogeny shows that 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 clusters with other Bcsl group members within the 10.1601/nm.4857 clade. However, the low bootstrap values confirm the limitations of 16S rRNA as a discriminatory marker within the Bcsl species group. Second, we applied an MLST approach based on the scheme by Priest et al. [36]. This revealed that MYBT18246 clusters with the toxin cured 10.1601/nm.5000 Bt407, insecticidal 10.1601/nm.5000 serovar chinensis CT-43, and with the nematicidal 10.1601/nm.5000 YBT-1518 within the Bcsl phylogeny (Fig. 2b). Based on this phylogeny and the phenotypic defining feature of the 10.1601/nm.5000 species group (the ability to produce crystal toxins against invertebrates and nematodes), the strain 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 can be safely classified as nematicidal 10.1601/nm.5000.

For a detailed analysis of encoded toxins in 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246, we generated a local database consisting of all available Cry, Cyt, Vip and Sip protein sequences from UniProtKB [71] and GenBank [72]. The database was curated to generate a set of non-redundant reference toxins. In total, we identified three different cry toxin genes in the 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 genome and classified them as cry13Aa2 (>95%), cry13Ba1 (<78%) and cry13Ab1 (<95%), based on the similarity scheme from the Cry-toxin naming committee by Crickmore [13, 70]. Notably, these cry toxin genes are encoded on the chromosome and not on extra-chromosomal elements as has been previously reported for the vast majority of cry toxin genes [7, 73, 74]. The toxin gene analysis revealed four additional putative toxin-like genes on plasmids with sequence similarity to cry genes and vip genes. A Pfam domain analysis using InterPro [75] revealed a p120510 encoded putative Vip-like toxin, a p120416 encoded putative Cry-like toxin and two p109822 encoded putative Bin-like toxins with potential for future studies.

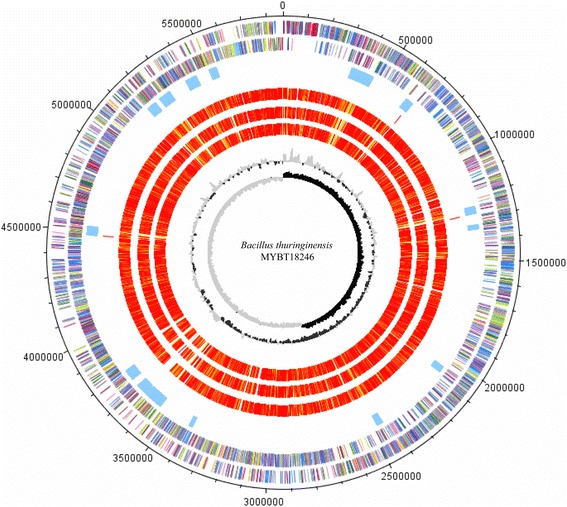

Additionally, the 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 chromosome was screened for prophage regions by using the Phage Search Tool with default parameters. PHAST identifies prophage regions based on key genes from a reference database and defines the boundaries using a genomic composition-based algorithm. For a more detailed description see [76]. A total of 16 putative prophage loci were identified in the chromosome, including three that were associated with the previously identified chromosomally encoded cry toxin genes. As shown in Fig. 3, the cry toxins (displayed in red, track 4) are located in close proximity to identified prophage regions (displayed in blue, track 3). Furthermore, all 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 extra-chromosomal elements were also screened for prophages to check whether we could identify phages that reside in a linear or circular state in the host, as has been reported in 2013 by Fortier et al. [77]. Apparently, intact phage regions were identified according to the PHAST score system on p150790, p120416, p109822, p101287 and p46701.

Fig. 3.

Circular visualization of the genome comparison of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 with 3 other sequenced 10.1601/nm.5000 strains. The tracks from the outside represent: (track 1–2) Genes encoded by the leading and lagging strand of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 marked in COG colors [93]; (track 3) putative prophage regions, identified with PHAST in blue [76], (track 4) identified cry toxin genes in red; (track 5–7) orthologs for the genomes of 10.1601/nm.5000 YBT-1518 (CP005935.1), 10.1601/nm.5000 CT-43 (CP001907.1), 10.1601/nm.5000 Bt407 (CP003889.1) illustrated in red to light yellow, singletons in grey (grey: <1e−20; light yellow: 1e−21–1e−50; gold: 1e−51–1e−90; light orange: 1e−91–1e−100; orange: 1e−101–1e−120; red: >1e−121 (track 7) % GC plot (track 8), GC skew [(GC)/(G + C)]. Visualization was done with DNAPlotter [94]

The finding of prophage associated cry genes in strain MYBT18246 indicates that phages may serve as vectors for the transmission of virulence factors within the species 10.1601/nm.5000 . This resembles the previously described lysogenic conversion of pathogens by phages [78], supporting the idea that phages may represent a driving force for the distribution of fitness factors as well as virulence factors [78–80]. The finding that toxins, which are generally specific for a certain type of host organism, are located within a mobile genomic element in the chromosome of this bacterium, suggests that phages of strain MYBT18246 may contribute to adaptation to different hosts [81–83].

Extended insights

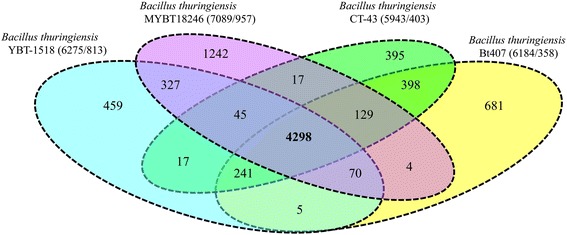

Based on the proximity within the tree (Fig. 2b), the genomes of 10.1601/nm.5000 Bt407, 10.1601/nm.5000 serovar chinensis CT-43 and 10.1601/nm.5000 YBT-1518 were identified as closest relatives and selected for an in depth comparative analysis. Shared gene contents were determined, visualized and compared, with a focus on known virulence factors such as cry toxins and pathogenic driving forces such as phages. The analysis revealed unique as well as shared gene contents for each strain (Fig. 3). In Fig. 3 the outer rings represent the genes on the leading and lagging strand with COG classification. The inner rings (track 5–7) illustrate the orthologous genes of 10.1601/nm.5000 YBT-1518, 10.1601/nm.5000 CT-43, 10.1601/nm.5000 Bt407 in red (high similarity) to light yellow (low similarity), and white (no similarity). The circular representation of the chromosome comparison revealed that prophages are a major source of regional differences between the strains (Fig. 3). Additionally, the pan-genome of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 compared to the three closest relatives was determined (Fig. 4). Orthologous genes between all four organisms were identified by comparing the whole genomes using Proteinortho [84] with a similarity cutoff of 50% and an E-value of 1e−10. Gbk-files were downloaded from NCBI and the protein sequences were extracted using cds_extractor v0.7.1 [85]. Detected paralogous genes are displayed in the Venn diagram in Fig. 4. All four strains share a core genome of 4298 genes. This is equivalent to 67% of each genome. 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 shares 4 additional genes exclusively with 10.1601/nm.5000 Bt407, 17 genes with 10.1601/nm.5000 serovar chinensis CT-43 and 327 genes with 10.1601/nm.5000 YBT-1518. 10.1601/nm.5000 serovar chinensis CT-43 and 10.1601/nm.5000 Bt407 share 398 orthologous genes. Notably, the genome of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 contains 1242 orphan genes and thus two to threefold more singletons than the compared genomes. This result confirms the high degree of conservation of the four 10.1601/nm.5000 strains (Fig. 2a and b) and it also refines the phylogenetic relationship of the strains to each other based on non-orthologous regions. Singletons are located on the chromosome as well as on extra-chromosomal elements. The density of singletons is higher (2.5 fold) on the plasmids. Notably, all major chromosomal differences can be attributed to prophage regions. All gene products were assigned to COG categories and investigated for PFAM domains and Signal peptides (Table 6). In detail, those genes code for: (i) phage proteins, (ii) morons (virulence factors), (iii) a vast majority of proteins with cryptic function. This is supported by Fig. 3 which clearly shows that the regions of differences (track 5–7) directly correspond to the regions of identified phages (track 3). Moreover, the identified cry toxins (track 4) are adjacent to identified prophage regions and could be suggested as morons. Additionally, the singletons were screened for further virulence factors and genes encoding type-IV secretion system, C5-methyltransferase, type-restriction enzymes, sporulation, resistance and genes involved in genetic competence were identified. In particular, the finding of restriction-modification systems indicates a protection mechanism against other phages and plasmids and thus forms a putative barrier against further genomic modification.

Fig. 4.

Venn diagram of the genome comparison of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 with other 10.1601/nm.5000 strains. Venn diagram displays the orthologous genes between 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 (CP015350-CP015361), 10.1601/nm.5000 YBT-1518 (CP005935-CP002486), 10.1601/nm.5000 serovar chinensis CT-43 (CP001907-CP001917) and 10.1601/nm.5000 Bt407 (CP003889-CP003898). Ortholog detection was performed with Proteinortho [84] including protein blast with a similarity cut-off of (50%) and an E-value of 1e−10. The total number of genes and paralogs are depicted under the corresponding species name. Open reading frames that were classified as pseudogenes were not included in this analysis

Table 6.

General genome features of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 and close relatives

| Genome features | Genome name | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246a | 10.1601/nm.5000 407b | 10.1601/nm.5000 YBT-1518c | 10.1601/nm.5000 CT-43d | |

| Sequencing status | Finished | Finished | Finished | Finished |

| Genome size (Mbp) | 6.75 | 6.13 | 6.67 | 6.15 |

| DNA coding (bp) | 5,623,665 | 5,133,026 | 5,421,574 | 5,079,667 |

| GC (%) | 35.4 | 35.02 | 35.29 | 35.12 |

| DNA scaffolds | 12 | 10 | 7 | 11 |

| Total gene count | 7239 | 6442 | 6738 | 6252 |

| Protein coding genes (%) | 97.9 | 95.9 | 98.0 | 95.1 |

| RNA genes | 151 | 180 | 139 | 124 |

| Genes in internal clusters | 2694 | 489 | 370 | 334 |

| Genes with function prediction | 5274 | 4615 | 5193 | 4211 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 4662 | 3634 | 3746 | 3505 |

| Genes with Pfam domains | 5503 | 4991 | 5333 | 4809 |

| Genes with signal peptides | 500 | 447 | 471 | 418 |

| Genes with transmembrane helices | 1863 | 1750 | 1854 | 1698 |

| CRISPR repeats | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Conclusion

In this work we present the whole-genome sequence of 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 and its specific genome features. The genome includes three nematicidal cry13 gene variants located on the chromosome, which were named according to sequence similarity as stated by the Cry Toxin Nomenclature Committee, as cry13Aa2, cry13Ba1, and cry13Ab1. Four additional putative toxin genes were identified with low sequence similarity to other known toxins on plasmids: p120510 (Vip-like toxin), p120416 (Cry-like toxin) and p109822 (two Bin-like toxins). These toxins contained complete toxin domains, yet the activity against potential hosts should be elucidated in future studies. The genome comprises a large number of mobile elements involved in genome plasticity including eleven plasmids and sixteen chromosomal prophages. Both plasmids and prophages are important HGT elements indicating that they are an important driving force for the evolution of pathogens. The most striking finding is the close proximity of the chromosomal nematicidal cry toxin genes to three distinct prophages indicating a contribution of phages in defining the host range of this strain. 10.1601/nm.5000 MYBT18246 may show potential as a biocontrol agent against nematodes which should be addressed in future experiments.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sascha Dietrich and Andreas Leimbach for bioinformatic support. We as well thank Nicole Heyer and Simone Severitt for excellent technical assistance.

Funding

We thank the German Research Foundation (DFG-SPP1399, Grant LI 1690/2–1 to HL; SCHU 1415/9 to HS, and RO 2994/3 to PR) for financial support. We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University.

Abbreviation

- B

10.1601/nm.4857

- B. thuringiensis

10.1601/nm.5000

- Bcsl

10.1601/nm.4885 sensu lato

- Cry

Crystal

- Cyt

Cytolytic

- IMG

Integrated Microbial Genomes

- MLST

Multi-locus sequence typing

- PHAST

Phage Search Tool

- Sip

Secreted insecticidal protein

- SMRT

Single molecule real-time

- Vip

Vegetative insectididal protein

Authors’ contributions

HL and HS designed the study. AP supervised the genome analysis. JH corrected the annotation, analyzed the genome with focus on comparative genomics. JH, AP and HL wrote the manuscript. BB, CS and PR performed the genome sequencing. HL performed the assembly and the annotation of the sequence data. JH performed the microscopy of strain MYBT18246. AS and CS isolated the genomic DNA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bechtel DB, Bulla LA, Kramer KJ, Bechtel DB, David- LI. Electron microscope study of Sporulation and Parasporal crystal formation in Bacillus thuringiensis. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:1472–1481. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1472-1481.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibrahim MA, Griko N, Junker M, Bulla LA. Bacillus thuringiensis: a genomics and proteomics perspective. Bioeng Bugs. 2010;1:31–50. doi: 10.4161/bbug.1.1.10519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carozzi NB, Kramer VC, Warren G, Evola S, Koziel MG. Prediction of insecticidal activity of Bacillus thuringiensis strains by polymerase chain reaction product profiles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3057–3061. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.11.3057-3061.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iriarte J, Porcar M, Lecadet M-M, Caballero P. Isolation and characterization of Bacillus thuringiensis strains from aquatic environments in Spain. Curr Microbiol. 2000;40:402–408. doi: 10.1007/s002840010078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RA, Couche GA. The phylloplane as a source of Bacillus thuringiensis variants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:311–315. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.311-315.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burges D, Hurst JA. Ecology of Bacillus thuringiensis in storage moths. J Invertebr Pathol. 1977;30:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(77)90210-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schnepf E, Crickmore N, Van RJ, Lereclus D, Baum J, Feitelson J, et al. Bacillus thuringiensis and its Pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:775–806. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.775-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanahuja G, Banakar R, Twyman RM, Capell T, Christou P. Bacillus thuringiensis: a century of research, development and commercial applications. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9:283–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vidal-Quist JC, Castañera P, González-Cabrera J. Diversity of Bacillus thuringiensis strains isolated from citrus orchards in Spain and evaluation of their insecticidal activity against Ceratitis Capitata. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;19:749–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feitelson J. The Bacillus thuringiensis family tree. In: Kim L, editor. Advanced engineered pesticides. 1st. New York: CRC Press; 1993. pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vos P, Garrity GM, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, et al. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. In: Vos P, Garrity G, Jones D, Krieg NR, Ludwig W, Rainey FA, Schleifer K-H, Whitman W, et al., editors. Volume 3: the Firmicutes. 2nd. New York: Springer; 2009. pp. 1–1317. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabha ME-S, Adayel SA, El-Masry SA, Alazazy H. Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin for the control of citrus trees snails. Researcher. 2013;5:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palma L, Muñoz D, Berry C, Murillo J, Caballero P. Bacillus thuringiensis toxins: an overview of their Biocidal activity. Toxins (Basel). 2014;6:3296–3325. doi: 10.3390/toxins6123296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crickmore N. Bacillus thuringiensis Toxin nomenclature. http://www.btnomenclature.info/. Accessed 12 Oct 2016.

- 15.Aronson AI. The two faces of Bacillus thuringiensis: insecticidal proteins and post-exponential survival. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:489–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchis V, Bourguet D. Bacillus thuringiensis: applications in agriculture and insect resistance management. A review Agron Sustain Dev. 2008;28:11–20. doi: 10.1051/agro:2007054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohn F. Untersuchungen über Bakterien. Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen. 1872;1:127–224. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skerman V, McGowan V, Sneath P. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1980;30:225–420. doi: 10.1099/00207713-30-1-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott E, Dyer DW. Divergence of the SigB regulon and pathogenesis of the Bacillus cereus Sensu Lato group. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:564. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankland GC, Frankland PF. Studies on some New Micro-Organisms obtained from Air. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 1887. p. 257–87.

- 21.Ernst B. Ueber die Schlaffsucht der Mehlmottenraupe (Ephestia kuhniella) und ihren Erreger Bacillus thuringiensis n. sp. Zeitschrift für Angew Entomol. 1915;2:21–56. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flügge C. Die Mikroorganismen. 2.Auflage. Leipzig, Germany: F.C.W. Vogel; 1886. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakamura LK. Bacillus pseudomycoides sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:1031–1035. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-3-1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lechner S, Mayr R, Francis KP, Prüss BM, Kaplan T, Wießner-Gunkel E, et al. Bacillus weihenstephanensis sp. nov. is a new psychrotolerant species of the Bacillus cereus group. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:1373–1382. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guinebretière MH, Auger S, Galleron N, Contzen M, de Sarrau B, de Buyser ML, et al. Bacillus cytotoxicus sp. nov. is a novel thermotolerant species of the Bacillus cereus group occasionally associated with food poisoning. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2013;63:31–40. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.030627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiménez G, Urdiain M, Cifuentes A, López-López A, Blanch AR, Tamames J, et al. Description of Bacillus toyonensis sp. nov., a novel species of the Bacillus cereus group, and pairwise genome comparisons of the species of the group by means of ANI calculations. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2013;36:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oren A, Garrity GM. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64:1–5. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.060285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung MY, Paek WK, Park IS, Han JR, Sin Y, Paek J, et al. Bacillus gaemokensis sp. nov., isolated from foreshore tidal flat sediment from the Yellow Sea. J Microbiol. 2010;48:867–871. doi: 10.1007/s12275-010-0148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung MY, Kim JS, Paek WK, Lim J, Lee H, Kim PI, et al. Bacillus manliponensis sp. nov., a new member of the Bacillus cereus group isolated from foreshore tidal flat sediment. J Microbiol. 2011;49:1027–1032. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-1049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu B, Liu GH, Hu GP, Cetin S, Lin NQ, Tang JY, et al. Bacillus bingmayongensis sp. nov., isolated from the pit soil of emperor Qin’s Terra-cotta warriors in China. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2014;105:501–510. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NL; Validation of the publication of new names and new combinations previously effectively published outside the IJSB. List No. 65. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48(Pt 2):627. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Helgason E, Okstad OA, Caugant DA, Johansen HA, Fouet A, Mock M, et al. Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and Bacillus thuringiensis--one species on the basis of genetic evidence. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2627–2630. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.6.2627-2630.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okinaka TR, Keim P, Okinaka RT, Keim P. The Phylogeny of Bacillus cereus sensu lato. Microbiol Spectr. 2016;4 doi:10.1128/microbiolspec. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Rasko DA, Altherr MR, Han CS, Ravel J. Genomics of the Bacillus cereus group of organisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:303–329. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt TR, Scott EJ, II, Dyer DW. Whole-genome phylogenies of the family Bacillaceae and expansion of the sigma factor gene family in the Bacillus cereus species-group. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:430. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Priest FG, Barker M, Baillie LWJ, Holmes EC, Maiden MCJ. Population structure and evolution of the Bacillus cereus group. Society. 2004;186:7959–7970. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7959-7970.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu H, Zhang J, Huang D, Gao J, Song F. Characterization of Bacillus thuringiensis strain Bt185 toxic to the Asian cockchafer: Holotrichia parallela. Curr Microbiol. 2006;53:13–17. doi: 10.1007/s00284-005-0097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ackermann H-WW, Azizbekyan RR, Bernier RL, Barjac H, Saindoux S, Valero JR, et al. Phage typing of Bacillus subtilis and B. thuringiensis. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:643–657. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)81062-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahillon J, Rezsöhazy R, Hallet B, Delcour J. IS231 and other Bacillus thuringiensis transposable elements: a review. Genetica. 1994;93:13–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01435236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kronstad JW, Whiteley HR. Inverted repeat sequences flank a Bacillus thuringiensis crystal protein gene. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:95–102. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.95-102.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masri L, Branca A, Sheppard AE, Papkou A, Laehnemann D, Guenther PS, et al. Host–pathogen Coevolution: the selective advantage of Bacillus thuringiensis virulence and its cry toxin genes. PLoS Biol. 2015;13:e1002169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulte RD, Makus C, Hasert B, Michiels NK, Schulenburg H. Multiple reciprocal adaptations and rapid genetic change upon experimental coevolution of an animal host and its microbial parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7359–7364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003113107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Payne J. Isolates of Bacillus thuringiensis that are active against nematodes. 1992.

- 44.Payne J, Cannon R, Bagley A. Bacillus thuringiensis isolates for controlling acarides. 1993.

- 45.Schnepf H, Schwab G, Payne J, Narva K, Foncerrada L. Nematicidal proteins. 2001.

- 46.Barjac H, Frachon E. Classification of Bacillus thuringiensis strains. Entomophaga. 1990;35:233–240. doi: 10.1007/BF02374798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gibbons NE, Murray RGE. Proposals concerning the higher Taxa of bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1978;28:1–6. doi: 10.1099/00207713-28-1-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.West AW, Burges HD, Dixon TJ, Wyborn CH. Survival of Bacillus thuringiensis and Bacillus cereus spore inocula in soil: effects of pH, moisture, nutrient availability and indigenous microorganisms. Soil Biol Biochem. 1985;17:657–665. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(85)90043-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ash C, Farrow JA, Dorsch M, Stackebrandt E, Collins MD. Comparative analysis of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, and related species on the basis of reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41(3):343–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing Phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11030–11035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;7:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Markowitz VM, Chen IMA, Palaniappan K, Chu K, Szeto E, Grechkin Y, et al. IMG: the integrated microbial genomes database and comparative analysis system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:115–122. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Field D, Garrity G, Gray T, Morrison N, Selengut J, Tatusova T, et al. The minimum information about a genome sequences (MIGS) specification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:541–547. doi: 10.1038/nbt1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gilles A, Meglécz E, Pech N, Ferreira S, Malausa T, Martin J-F. Accuracy and quality assessment of 454 GS-FLX titanium pyrosequencing. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rhoads A, Au KF. PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genomics, Proteomics Bioinforma. 2015;13:278–289. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staden R, Beal KF, Bonfield JK. The Staden package, 1998. In: Misener S, Krawtz AS, editors. Methods in molecular biology. New York: Humana Press; 1999. pp. 115–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chin C-S, Alexander DH, Marks P, Klammer AA, Drake J, Heiner C, et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2013;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.PacBio Software Downloads. 2016. http://www.pacb.com/support/software-downloads/. Accessed 12 Apr 2016.

- 60.Gao F, Luo H, Zhang C-T. DoriC 5.0: an updated database of oriC regions in both bacterial and archaeal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41 Database issue:D90–3. doi:10.1093/nar/gks990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.DoriC: an updated database of bacterial and archaeal replication origins. http://tubic.tju.edu.cn/doric/. Accessed 15 Dec 2016.

- 62.Gao F, Zhang C-T. Ori-finder: a web-based system for finding oriCs in unannotated bacterial genomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sheppard AE, Poehlein A, Rosenstiel P, Liesegang H, Schulenburg H. Complete genome sequence of Bacillus thuringiensis strain 407 cry. Genome Announc. 2013;1:158–112. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00158-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hyatt D, Chen G-L, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Stærfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Laslett D, Canback B. ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:11–16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Griffiths-Jones S, Bateman A, Marshall M, Khanna A, Eddy SR. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:439–441. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Crickmore N, Zeigler DR, Feitelson J, Schnepf E, Van Rie J, Lereclus D, et al. Revision of the nomenclature for the Bacillus thuringiensis pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:807–813. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.807-813.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bateman A, Martin MJ, O’Donovan C, Magrane M, Apweiler R, Alpi E, et al. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D204–D212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Benson DA, Cavanaugh M, Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, et al. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:36–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Carlson CR, Kolstø A-BB. A complete physical map of a Bacillus thuringiensis chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1053–1060. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1053-1060.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang A, Pattemore J, Ash G, Williams A, Hane J. Draft genome sequence of Bacillus thuringiensis strain DAR 81934, which Exhibits Molluscicidal Activity. Genome Announc. 2013;1:e0017512. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00175-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mitchell A, Chang HY, Daugherty L, Fraser M, Hunter S, Lopez R, et al. The InterPro protein families database: the classification resource after 15 years. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D213–D221. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou Y, Liang Y, Lynch KH, Dennis JJ, Wishart DS. PHAST: a fast phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(SUPPL. 2):347–352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fortier L-C, Sekulovic O. Importance of prophages to evolution and virulence of bacterial pathogens. Virulence. 2013;4:354–365. doi: 10.4161/viru.24498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brüssow H, Canchaya C, Hardt W-D, Bru H. Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to Lysogenic conversion. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:560–602. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.560-602.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barksdale L, Arden SB. Persisting bacteriophage infections, lysogeny, and phage conversions. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1974;28:265–299. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.28.100174.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Freeman VJ. Studies on the virulence of bacteriophage-infected strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. J Bacteriol. 1951;61:675–688. doi: 10.1128/jb.61.6.675-688.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Maagd RA, Bravo A, Crickmore N. How Bacillus thuringiensis has evolved specific toxins to colonize the insect world. Trends Genet. 2001;17:193–199. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Agaisse H, Lereclus D. How does Bacillus thuringiensis produce so much insecticidal crystal protein? J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6027–6032. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6027-6032.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ben-Dov E. Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis and its Dipteran-specific toxins. Toxins (Basel) 2014;6:1222–1243. doi: 10.3390/toxins6041222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lechner M, Findeiss S, Steiner L, Marz M, Stadler PF, Prohaska SJ. Proteinortho: detection of (co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leimbach A. bac-genomics-scripts: Bovine E. coli mastitis comparative genomics editio. 2016. https://github.com/aleimba/bac-genomics-scripts/tree/master/cds_extractor ,Accessed 14 Mar 2016.

- 86.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Euzéby J. List of new names and new combinations previously effectively, but not validly, published. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2010;60:469–472. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.022855-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H, Whitman WB. Class I. Bacillis class nov. Bergey’s Man Syst Bacteriol. 2009;3:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Prévot AR. Dictionnaire des Bactéries Pathogènes In: Hauderoy P, Ehringer G, Guillot G, Magrou. J., Prévot AR, Rosset D, Urbain A (eds), Dictionnaire des Bactéries Pathogènes, Second Edition, Masson et Cie, Paris, 1953, p. 1–692.

- 90.Fischer A. Untersuchungen über bakterien. Jahrbücher für Wissenschaftliche Botanik. 1895;27:1–163. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ash C, Priest FG, Collins MD. Molecular identification of rRNA group 3 bacilli (Ash, Farrow, Wallbanks and Collins) using a PCR probe test. Proposal for the creation of a new genus Paenibacillus. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 64:253–60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8085788. Accessed 6 Jun 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, et al. The COG database: an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, Parkhill J. DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:119–120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]