Abstract

Background

Acute angioedema of the upper airways can be life-threatening. An important distinction is drawn between mast-cell-mediated angioedema and bradykinin-mediated angioedema; the treatment of these two entities is fundamentally different.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent articles retrieved by a selective search in PubMed and on guidelines concerning the treatment of angioedema. The authors draw on their own clinical experience in their assessment of the literature.

Results

In the emergency clinical situation, the most important information comes from accompanying manifestations such as itching and urticaria and from the patient’s drug history and family history. When angioedema affects the head and neck, securing the upper airways is the highest priority. Angioedema is most commonly caused by mast-cell mediators, such as histamine. This type of angioedema is sometimes accompanied by urticaria and can be effectively treated with antihistamines or glucocorticoids. In case of a severe allergic reaction or anaphylaxis, epinephrine is given intramuscularly in a dose that is adapted to the patient’s weight (150 µg for body weight >10 kg, 300 µg for body weight >30 kg). Bradykinin-mediated angioedema may arise as either a hereditary or an acquired tendency. Acquired angioedema can be caused by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and by angiotensin II receptor blockers. Bradykinin-mediated angioedema should be treated specifically with C1-esterase inhibitor concentrates or bradykinin-2 receptor antagonists.

Conclusion

Angioedema of the upper airways requires a well-coordinated diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Steroids and antihistamines are very effective against mast-cell-mediated angioedema, but nearly useless against bradykinin-mediated angioedema. For angioedema induced by ACE inhibitors, no causally directed treatment has yet been approved.

The diagnostic evaluation and treatment of acute angioedema are challenging. The condition presents in the form of clinically easily confused symptoms, which arise from different pathophysiological mechanisms. Trigger factors include allergic reactions; food intolerances; genetic variants—as in hereditary angioedema (HAE); infections, and reactions to medications—for example, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. In some patients, no cause can be found in spite of laborious differential diagnostic evaluation (idiopathic angioedema). If angioedema manifests in the upper respiratory tract, this presents a life-threatening situation because of the unpredictable further course. In such cases, coordinated interdisciplinary airway management and adjusted pharmacotherapy are required.

Patients with acute angioedema consult not only dermatologists/allergologists, who are among the first ports of call because of the manifestation involving cutis and subcutis and the close association with dermatological symptoms. Children with edema, for example, usually present to their treating pediatrician. If the angioedema is located in the aerodigestive tract, patients will seek out a specialist in ear, nose, and throat (ENT) medicine. General practitioners and specialists in internal medicine are also involved: in the general emergency admission wards and because they would usually prescribe ACE inhibitors. Anesthetists and emergency physicians play a major part in securing airway functioning if the edema manifests in the respiratory tract.

Methods

We conducted a selective literature search in PubMed, using the search terms “(acute) angioedema“. “emergency“, and “therapy“/“treatment“. Furthermore, we considered current guidelines for the treatment of angioedema. Our own clinical experience, gained in the angioedema center of the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, at Ulm University Medical Center, formed another cornerstone in the context of elective and emergency-related treatment for patients.

Epidemiology

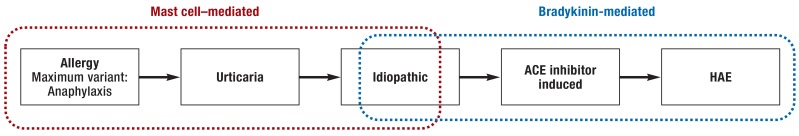

Most of the cases of angioedema that require treatment in emergency departments are mast cell mediated or idiopathic. Some of them are accompanied by urticaria or are associated with anaphylaxis (figure 1) (table 1) (1). Altogether, very few exact epidemiological studies exist on the incidence of angioedema in anaphylactic or allergic reactions. The guideline of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, AWMF) for the acute treatment and management of anaphylaxis reports that 1% of patients attend hospital emergency departments because of anaphylactic reactions (2).

Figure 1.

Epidemiology of angioedema, from left to right with decreasing frequency

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; HAE, hereditary angioedema

Table 1. Definition, triggers, and symptoms of urticaria and allergy/anaphylaxis*.

| Definition | Trigger factors | Symptoms | |

| Urticaria | Duration of symptoms | ||

| Acute, spontaneous | <6 weeks | Often idiopathic, infections, drugs, foods, allergy, intolerance | Urticaria can affect the entire integument, angioedema affecting in particular the face, head-neck region; occasionally abdominal symptoms, dyspnea, dysphagia, pruritus |

| Chronic, spontaneous | >6 weeks | Foods, infections, inflammations, allergy, intolerance, (auto)antibody | |

| Inducible/physically triggerable urticaria (eg, cold urticaria, pressure urticaria, vibratory urticaria) |

Specific triggering physical mechanism | Exogenous physical factors (cold, such as cold drinks), light, mechanical pressure | Efflorescences often limited to site of contact, but can generalize depending on subtype; occasionally extracutaneous symptoms such as fever, dizziness, nausea, headache, pruritus, dyspnea, dysphagia |

| Allergy | |||

| Type-I reaction | Within seconds or minutes: IgE mediated immunologic reaction to allergen | For example, foods, insect bites, drugs; after prior sensitization | For example, conjunctivitis, rhinitis, bronchial asthma, angioedema, urticaria |

| Anaphylaxis | |||

| Complication/aggravation/maximum variant of allergic reaction | For example, foods, insect bites, medications; after prior sensitization | The classification follows the most severe symptoms experienced (no symptom is obligatory) | |

| Grade I | Symptoms limited to skin | Acute urticaria and angioedema, erythema, flushing, pruritus | |

| Grade II | Mild systemic reactions | Additionally: obstructed airway (rhinorrhea, cough, stridor, dyspnea), tachycardia, hypotension, arrhythmia, gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting) | |

| Grade III | Severe systemic reactions | Additionally: defecation, laryngeal edema, bronchospasm, cyanosis, shock | |

| Grade IV | Life-threatening reactions | Additionally: respiratory arrest, circulatory arrest | |

The incidence of severe anaphylaxis is 1–3/10 000 persons in the general population (3). Angioedema, however, accompanies 46% of all anaphylactic reactions, and respiratory symptoms (dyspnea or stridor, for example) occur in 67% of all cases of anaphylaxis (4).

A US multicenter analysis of the triggers of angioedema that necessitated treatment on an inpatient basis found that in 93% of cases, drugs were responsible (primarily ACE inhibitors, aspirin, and non-steroidal antirheumatic drugs (NSAR). Of the 69 admitted inpatients with moderate to severe angioedema, 20 had to be intubated over the course of their illness (5). A retrospective study from France analyzed 25 patients with acute angioedema induced by ACE inhibitor use. In 44% of cases the swellings manifested as laryngeal edema, in three patients (12%), a mechanical protective measure was required (tracheostomy or intubation) (6).

Angioedema subsequent to ACE inhibitor use occurs in 0.2–0.7% of patients, depending on the substance (7). Ethnic differences have been observed: dark-skinned persons have three times the risk for developing ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema (8) as do Caucasian white persons. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP) inhibitors (for example, gliptins) or neprilysin inhibitors (for example, sacubitril) can increase the probability of angioedema significantly when combined with ACE inhibitors or sartans. Whether they cause bradykinin-mediated angioedema when used as monotherapy is not known to date (9).

The estimated incidence of HAE is 1:50 000, independent of ethnicity or sex (10). Only 0.9% of all HAE attacks affect the larynx, but half of HAE patients will experience a laryngeal attack at least once in their lifetime (11). It is important to know that edema in HAE patients can extend and affect additional organs or localizations. Studies have shown that in 14–29% of all facial swellings in HAE patients, the larynx is affected too—either simultaneously or within the following 24 hours (11, 12).

Clinical symptoms and course

Mast cell–mediated angioedema

Mast cell–mediated angioedema—owing to the release of the tissue hormone histamine, among others—manifests as symptoms of allergic reactions, urticaria, or pseudoallergic episodes. By contrast to bradykinin-mediated angioedema it is often associated with pruritus and/or the occurrence of urticaria/hives (13). Edema manifestation in the aerodigestive tract presents a medical emergency. Foodstuffs, insect venom, drugs, and latex are among the most common triggers (14).

Bradykinin-mediated angioedema

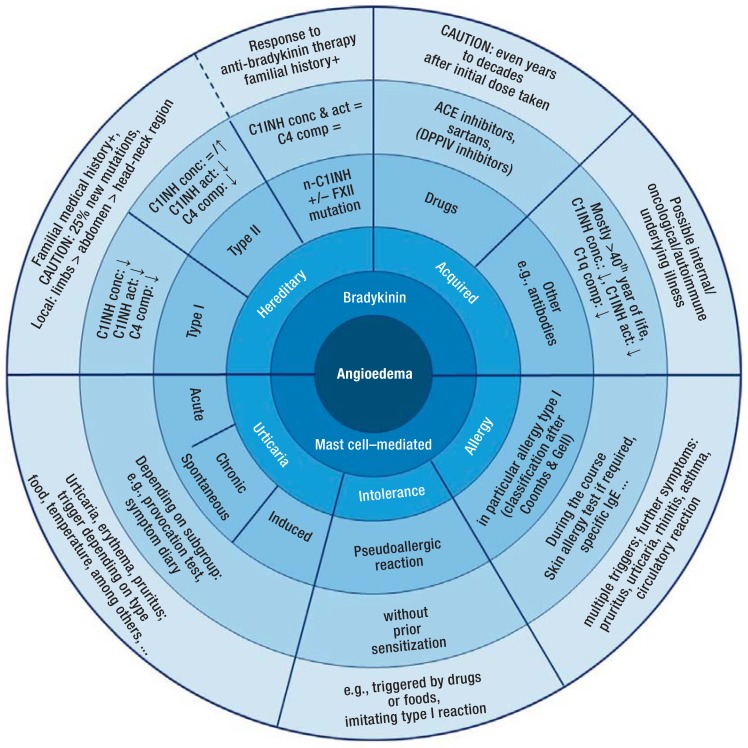

Primarily bradykinin-mediated angioedema can be hereditary or acquired (15) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical symptoms and diagnostic evaluation of bradykinin-mediated and mast cell–mediated angioedema

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; C1INH conc & act, esterase inhibitor concentration and activity; C4 comp, C4 complement; C1q comp, C1q complement; DPPIV, dipeptidyl peptidase IV; n-C1INH, hereditary angioedema (HAE) with normal C1 esterase inhibitor values; +/– FXII mut, with or without mutation of Factor XII; ?, lowered; ?, raised; =, constant; +, positive; = /?, constant or raised

Because of a genetic variant, patients with HAE experience recurrent edematous attacks that can be localized anywhere on the entire body, including the inner organs. Initial symptoms of HAE manifest on average around the 10th year of life (16). Individual trigger factors are known (for example, hormones, medical interventions) (17). Angioedema in HAE can be localized around the entire body, often they affect the limbs or the gastrointestinal tract, more rarely the head and neck area (18). The attack rate differs individually and ranges from several angioedematous attacks per week to a few attacks per year. HAE patients are often correctly diagnosed late, as gastrointestinal angioedema, for example, is clinically non-specific and often misdiagnosed (19). Before adequate treatment options became available, mortality in unrecognized HAE patients was higher than 50% because of upper airway obstruction (20).

Acquired forms of angioedema include swellings caused by drugs, primarily ACE inhibitors or combinations of an ACE inhibitor with a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP) inhibitor, more rarely after intake of an angiotensin II receptor-1 (AT-1R) blocker (9, 21). ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema develops mostly within the initial months after the drug was first taken. In the literature, the latency period between first intake of the preparation and manifestation of angioedema varies between 1 day and 10 years, the median is 6 months. The reason for the wide variance in the latency period is not known (22, 23). Angioedema as an adverse effect of ACE inhibitors or sartans affect almost exclusively the head and neck area (tongue>lips>pharynx>larynx) (9). 10% of patients will experience obstruction of the upper respiratory tract as a result of the angioedema (24, 25). After the manifestation of drug-induced bradykinin-mediated angioedema, patients should immediately stop taking the preparation that served as the trigger. Studies have shown that where the pathomechanism is not known, some patients will develop further edema within a year of stopping taking the medication. This risk is greatest within the 4 weeks after patients have stopped taking the preparation (26, 27).

In the setting of malignancies, such as B-cell lymphoma, formation of antibodies can also trigger bradykinin-mediated angioedema. Furthermore, autoimmune forms with autoantibodies to the C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) are known (28).

Pathophysiology

Mast cell–mediated angioedema

Fundamentally, any substance in the environment can become a trigger for an allergy. After initial contact with the allergen, affected persons become sensitized, but clinical symptoms do not occur. In the sensitization phase, the allergen is taken up by antigen presenting cells, which activates T-helper cells. These then release interleukin 4, thus stimulating the synthesis of immunoglobulin (Ig) E antibodies (29). The second contact with the allergen results within minutes in the IgE-mediated degranulation of mast cells and basophile cells—because of the binding of the allergen to IgE molecules—and thus to the release of vasoactive and proinflammatory mediators, such as histamine, among others (30, 31). Histamine binds to Gq/11-protein–coupled H1 receptors, resulting in activation of phospholipase C, triggering the release of Ca2+ ions from intracellular vesicles, which, in turn, triggers the release of the potent vasodilator nitrogen monoxide (NO) from the vascular endothelium (32, 33).

Subepidermal mast cells have a crucial role in angioedema in the context of urticaria. Depending on the subcategory of urticaria, mast cells are degranulated because of certain trigger mechanisms, and mediators, such as histamine, are released. The exact underlying mechanism has not been clarified for all forms of urticaria, it is the subject of ongoing research (34).

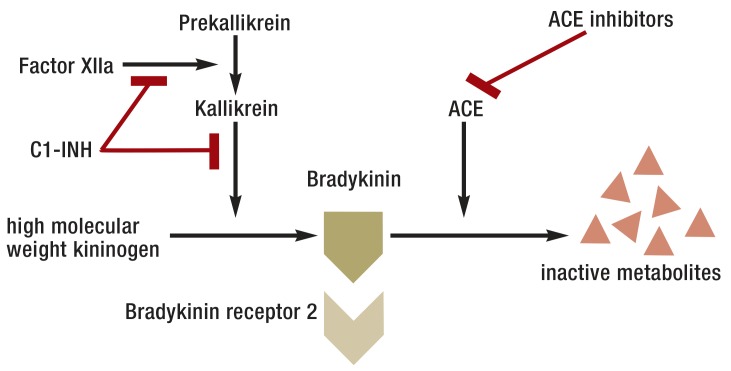

Bradykinin-mediated angioedema

The vasoactive peptide hormone bradykinin is formed by the kallikrein-kinin system, with C1-INH acting as an inhibitor (35, 36). Bradykinin is inactivated, for example, by ACE, DPP4, and neprilysin (37, 38). It acts by activating the G-protein-coupled bradykinin receptors 1 and 2 (BR1 and BR2). The effect of BR2 antagonists in the treatment of bradykinin mediated angioedema suggests that the underlying pathophysiology progresses primarily via the BR2 (18, 39, 40).

In HAE patients, more than 400 genetic variants have been described for the C1-INH coding gene (SERPING 1) to date. Most of the genetic variants follow an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, a new mutation is present in about 20% of patients (e1). The result is either reduced C1-INH synthesis (HAE type 1, ca. 85% of all patients) or a functional defect of the C1-INH (HAE type 2, ca. 15% of all patients) (e2). Rarely, a form of HAE with normal C1-INH concentration is seen, which is occasionally referred to as HAE type 3 (e3).

In patients with ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema, a degradation enzyme of bradykinin is inhibited, which triggers edema development (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Bradykinin formation and degradation (modified from[e4])

ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; C1-INH, C1 esterase inhibitor

Differential diagnostic evaluation

In the emergency setting, a diagnosis can be made exclusively on the basis of the medical history and the clinical symptoms. The presence of pruritus and urticaria are crucial pointers, as are the medication history and familial history. Persistent/progressive edema in spite of histamines and cortisone treatment should prompt the treating physician to consider the differential diagnosis of bradykinin mediated angioedema. Laboratory values play a part only during the further course. In suspected HAE, C1-INH can be determined quantitatively and qualitatively, and additionally the complement factor 4 (17) (figure 2).

Acute treatment

In all cases of angioedema in the head and neck region, securing the airway is the top priority (e5). If angioedema of increasing size is present in the upper aerodigestive tract while being treated adequately, accompanied by inspiratory stridor and/or reduced oxygen saturation, the indication for intubation and ventilation should be defined early. If transoral intubation is not possible because of the swelling, transnasal fiber-optic intubation is a possible alternative. Intubation entails a risk that the edema will increase massively as a result of the manipulation, which means that wherever possible, it should be done in readiness to perform coniotomy/cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy immediately.

Since mast cell–mediated angioedema is more common than bradykinin-mediated angioedema, swellings of unknown origin are usually treated primarily like mast cell–mediated angioedema, by using antihistamines and cortisone derivates. Clinically, antihistamines and glucocorticoids are ineffective in bradykinin-mediated angioedema, whereas they are the drugs of choice in mast cell–mediated angioedema (table 2) (7).

Table 2. Acute treatment of angioedema.

| Acute treatment (in adults) | ||||

| Histamine mediated angioedema | Bradykinin mediated angioedema | |||

| Urticaria | Allergy/anaphylaxis | HAE | Medication induced | Acquired C1-INH deficiency |

| Acute form: Mostly self limiting, responds well to antihistamines and glucocorticoids | – Adrenaline (i.m./i.v.) – Fast acting antihistamine (p.o./ i.v.) – Glucocorticoids (eg, prednisolone) [– β 2 -sympathomimetic (eg, salbutamol)] |

– C1-INH concentrate i. v. (human or recombinant) – Icatibant: BR2 antagonist, s.c. |

To date only

Off-label therapeutic options: – Antihistamine/ glucocorticoids (oral/i. v.) – C1-INH concentrate i. v. (human or recombinant) – Icatibant: BR2 antagonist, s.c. |

– In general: therapy for underlying paraneoplastic/ autoimmune disorder – Acute: Icatibant s.c. (off-label) |

| Physical form: Avoidance of triggers/stopping exposure, patient needs to be informed | ||||

BR2, bradykinin receptor 2; C1-INH, C1 esterase inhibitor; HAE, hereditary angioedema; i. m., intramuscular; p.o., oral; i. v., intravenous; s. c., subcutaneous

Angioedema in allergic reactions/anaphylaxis

Severe allergic reactions or anaphylaxis should be treated guideline-conform primarily by applying intramuscular adrenaline (AWMF guideline: strong consensus; intramuscular [i. m.]) using an autoinjector, adapted to patient‘s weight: >10 kg: 150 µg, >30 kg 300 µg adrenaline; 0.01 mL/kg body weight [1 mg/1 mL]). Further medications used in the acute setting are antihistamines and glucocorticoids (2, e6). Depending on the situation and preparation, antihistamines can be given orally (tablets/liquid) or intravenously (i.v.).

The approved daily dose of the antihistamine can be recommended as a single/individual dose (e7)/ The guideline‘s expert panel agrees, however, that in individual cases, oral antihistamines can be increased up to four times the daily single dose. Glucocorticoids can be administered p.r., p.o. (tablets/liquid), or i.v. Reviews have reported a non-specific membrane stabilizing effect within 10–30 minutes after the administration of high doses of glucocorticoids (500–1000 mg in adults) (e8).

Bradykinin-mediated angioedema

In Germany, a BR2 antagonist and C1-INH concentrates are licensed for the acute treatment of HAE (e9). The BR2 antagonist icatibant is available in pre-filled syringes for subcutaneous (s.c.) application which contain 30 mg icatibant (18). Human and recombinant C1-INH concentrates are available for i.v. therapy of acute HAE attacks (e10, e11). Depending on the preparation, the dose (international units, IU) will have to be adjusted to the patient‘s body weight. A large number of preparations is licensed to be used as self-treatment at home for patients and their relatives.

No licensed causal treatment exists to date for medication-induced, bradykinin-mediated angioedema, which means that it is treated—in the sense of a therapeutic attempt—like angioedema, in the context of an allergic reaction, with antihistamines and glucocorticoids. Current studies are aiming to bring about official license approval of anti-bradykinergic medication for this indication.

A multicenter double-blinded phase II study showed that acute treatment of ACE inhibitor–induced angioedema with the specific BR2 antagonist icatibant (30 mg s. c.) is significantly superior to i.v. treatment with an antihistamine (clemastine 2 mg) and glucocorticoid (prednisolone 500 mg). Each study arm included 15 adult patients with acute angioedema in the aerodigestive tract subsequent to treatment with ACE inhibitors. The primary clinical endpoint was the time to complete resolution of the angioedema after medication had been administered. In five patients in the icatibant group, the angioedema resolved completely within 4 hours, compared with none of the patients in the antihistamine group (P=0.02). The overall duration of the swelling was notably reduced in patients receiving icatibant (8.0 hours vs 27.1 hours, P=0.002), and the substance was well-tolerated (most common adverse effect: local erythema at puncture site). Three patients in the antihistamine/glucocorticoid group had to be given icatibant as rescue medication because of life-threatening progression of the angioedema. Emergency tracheostomy was necessary in one of these patients, which was not the case in the icatibant group. The case numbers are still too small for the preparation to be licensed in ACE-inhibitor–induced angioedema; for this reason, treatment in this indication is possible off-label only (7).

Case reports have shown that i.v. administration of C1-INH concentrates is effective in ACE-inhibitor–induced angioedema (35, e12). A large randomized study of the topic is currently in the recruitment phase (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01843530).

In all forms of angioedema involving head and neck, symptomatic treatment can be supportive. This includes measures such as:

Administration of fluids and oxygen (100% O2 at a high flow rate)

Correct positioning of the patient (raised upper body)

Vasoconstriction measures such as cooling, sympathomimetics

Stabilizing the patient‘s circulation

Analgesia if required.

Conclusions

Mast-cell–mediated (histamine, among others) and bradykinin-mediated angioedema are a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for the medical specialties involved. Angioedema should not be underestimated during its course, especially if the head and neck region is involved; because of its unpredictable development it requires intensive medical monitoring. The scarce knowledge that exists about bradykinin-mediated angioedema is not widespread and has to be passed on in a consistent and disciplined fashion, as its causal and potentially lifesaving treatment differs fundamentally from that of mast-cell–mediated angioedema.

The top priority in the emergency setting is to secure the patient‘s airway. Regarding emergency medical treatment, it is important to be aware that causal therapy for bradykinin-mediated angioedema is available in specialized clinics/hospitals only. As a rule, emergency vehicles are not equipped with this treatment.

If angioedema does not respond to treatment with antihistamines and glucocorticoids, differential diagnostic considerations should include bradykinin-mediated angioedema, and if the finding is positive, this should be treated accordingly. In ACE-inhibitor–induced angioedema this is currently possible on an off-label basis only. Current studies aim to achieve license approval for the causal medication for this diagnosis.

Key Messages.

Angioedema is subcategorized into mast-cell–mediated and bradykinin-mediated edema.

Mast-cell–mediated angioedema, in contrast to bradykinin-mediated angioedema, often goes hand in hand with urticaria and pruritus.

Angioedema triggered by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors can develop with a latency period of up to 10 years after the preparation was taken for the first time.

For the treatment of mast-cell–mediated angioedema, adrenaline, antihistamines, glucocorticoids, and ß2-sympathomimetics are readily available.

Bradykinin-mediated angioedema can be treated with C1 esterase inhibitor concentrates or icatibant (to date off-label only, depending on the indication).

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr Hahn has received reimbursement for conference delegate fees and travel expenses from CSL Behring and Shire Deutschland [Germany]. She has received lecture honoraria from CSL Behring.

Prof. Hoffman has received lecture honoraria and study funding (third party funds) from CSL Behring and Shire Deutschland [Germany].

Dr Nordmann-Kleiner has received reimbursement for conference delegate fees and travel expenses from CSL Behring and Shire Deutschland [Germany]. She has received lecture honoraria from CSL Behring.

Dr Trainotti has received reimbursement for conference delegate fees and travel expenses from CSL Behring and Bio Cryst. She has received lecture honoraria from CSL Behring.

PD Dr Greve has received reimbursement for conference delegate fees and travel expenses from Shire Deutschland [Germany] and CSL Behring. He has received lecture honoraria from CSL Behring and Shire Deutschland [Germany].

Dr Bock declares that no conflict of interest exists according to the guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

References

- 1.Moellman JJ, Bernstein JA, Lindsell C, et al. A consensus parameter for the evaluation and management of angioedema in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:469–484. doi: 10.1111/acem.12341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ring J, Beyer K, Biedermann T, et al. Guideline for acute therapy and management of anaphylaxis. Allergo J Int. 2014;23:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moneret-Vautrin DA, Morisset M, Flabbee J, Beaudouin E, Kanny G. Epidemiology of life-threatening and lethal anaphylaxis: a review. Allergy. 2005;60:443–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worm M, Edenharter G, Rueff F, et al. Symptom profile and risk factors of anaphylaxis in Central Europe. Allergy. 2012;67:691–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerji A, Oren E, Hesterberg P, Hsu Y, Camargo CA Jr, Wong JT. Ten-year study of causes of moderate to severe angioedema seen by an inpatient allergy/immunology consult service. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29:88–92. doi: 10.2500/aap2008.29.3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Javaud N, Charpentier S, Lapostolle F, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema and hereditary angioedema: a comparison study of attack severity. Intern Med. 2015;54:2583–2588. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.4181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bas M, Greve J, Stelter K, et al. A randomized trial of icatibant in ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:418–425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDowell SE, Coleman JJ, Ferner RE. Systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in risks of adverse reactions to drugs used in cardiovascular medicine. BMJ. 2006;332:1177–1181. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38803.528113.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bas M, Greve J, Strassen U, Khosravani F, Hoffmann TK, Kojda G. Angioedema induced by cardiovascular drugs. New players join old friends. Allergy. 2015;70:1196–1200. doi: 10.1111/all.12680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig T, Aygoren-Pursun E, Bork K, et al. WAO guideline for the management of hereditary angioedema. World Allergy Organ J. 2012;5:182–199. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e318279affa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Papadopoulou-Alataki E. Upper airway considerations in hereditary angioedema. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:20–25. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328334f629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bork K, Staubach P, Hardt J. Treatment of skin swellings with C1-inhibitor concentrate in patients with hereditary angio-oedema. Allergy. 2008;63:751–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Busse PJ, Buckland MS. Non-histaminergic angioedema: focus on bradykinin-mediated angioedema. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43:385–394. doi: 10.1111/cea.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panesar SS, Javad S, de Silva D, et al. The epidemiology of anaphylaxis in Europe: a systematic review. Allergy. 2013;68:1353–1361. doi: 10.1111/all.12272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maurer M, Bader M, Bas M, et al. New topics in bradykinin research. Allergy. 2011;66:1397–1406. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steiner UC, Weber-Chrysochoou C, Helbling A, Scherer K, Grendelmeier PS, Wuillemin WA. Hereditary angioedema due to C1—inhibitor deficiency in Switzerland: clinical characteristics and therapeutic modalities within a cohort study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2016;11 doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0423-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bas M, Adams V, Suvorava T, Niehues T, Hoffmann TK, Kojda G. Nonallergic angioedema: role of bradykinin. Allergy. 2007;62:842–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cicardi M, Banerji A, Bracho F, et al. Icatibant, a new bradykinin-receptor antagonist, in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:532–541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dispenza MC, Gutierrez M, Bajaj P, Craig TJ. The need for individualized hereditary angioedema acute action plans: Two case studies of misdiagnosed attacks and unnecessary surgeries. The Journal of Angioedema. 2013:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cicardi M, Bergamaschini L, Marasini B, Boccassini G, Tucci A, Agostoni A. Hereditary angioedema: an appraisal of 104 cases. Am J Med Sci. 1982;284:2–9. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198207000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makani H, Messerli FH, Romero J, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized trials of angioedema as an adverse event of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beltrami L, Zingale LC, Carugo S, Cicardi M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-related angioedema: how to deal with it. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5:643–649. doi: 10.1517/14740338.5.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bas M, Kojda G, Bier H, Hoffmann TK. ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema in the head and neck region A matter of time? HNO. 2004;52:886–890. doi: 10.1007/s00106-003-1017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerji A, Clark S, Blanda M, LoVecchio F, Snyder B, Camargo CA Jr. Multicenter study of patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema who present to the emergency department. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:327–332. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean DE, Schultz DL, Powers RH. Asphyxia due to angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor mediated angioedema of the tongue during the treatment of hypertensive heart disease. J Forensic Sci. 2001;46:1239–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faisant C, Armengol G, Bouillet L, et al. Angioedema triggered by medication blocking the renin/angiotensin system: retrospective study using the French national pharmacovigilance database. J Clin Immunol. 2016;36:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s10875-015-0228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beltrami L, Zanichelli A, Zingale L, Vacchini R, Carugo S, Cicardi M. Long-term follow-up of 111 patients with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-related angioedema. J Hypertens. 2011;29:2273–2277. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834b4b9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scully C, Langdon J, Evans J. Marathon of eponyms: 17 Quincke oedema (Angioedema) Oral Dis. 2011;17:342–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Secrist H, Chelen CJ, Wen Y, Marshall JD, Umetsu DT. Allergen immunotherapy decreases interleukin 4 production in CD4+ T cells from allergic individuals. J Exp Med. 1993;178:2123–2130. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.6.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimamura T, Shiroishi M, Weyand S, et al. Structure of the human histamine H1 receptor complex with doxepin. Nature. 2011;475:65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature10236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simons FE. Advances in H1-antihistamines. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2203–2217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra033121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akdis CA, Simons FE. Histamine receptors are hot in immunopharmacology. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smit MJ, Hoffmann M, Timmerman H, Leurs R. Molecular properties and signalling pathways of the histamine H1 receptor. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29 Suppl 3:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolkhir P, Church MK, Weller K, Metz M, Schmetzer O, Maurer M. Autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria: What we know and what we do not know. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:1772–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greve J, Bas M, Hoffmann TK, et al. Effect of C1-esterase-inhibitor in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:E198–E202. doi: 10.1002/lary.25113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dray A, Perkins M. Bradykinin and inflammatory pain. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:99–104. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lefebvre J, Murphey LJ, Hartert TV, Jiao Shan R, Simmons WH, Brown NJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity in patients with ACE-inhibitor-associated angioedema. Hypertension. 2002;39:460–464. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adam A, Cugno M, Molinaro G, Perez M, Lepage Y, Agostoni A. Aminopeptidase P in individuals with a history of angio-oedema on ACE inhibitors. Lancet. 2002;359:2088–2089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08914-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bas M, Greve J, Stelter K, et al. A randomized trial of icatibant in ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:418–425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wirth K, Hock FJ, Albus U, et al. Hoe 140 a new potent and long acting bradykinin-antagonist: in vivo studies. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;102:774–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12249.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Pappalardo E, Cicardi M, Duponchel C, et al. Frequent de novo mutations and exon deletions in the C1 inhibitor gene of patients with angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:1147–1154. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Kaplan AP, Greaves MW. Angioedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:373–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.09.032. quiz 389-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Dewald G, Bork K. Missense mutations in the coagulation factor XII (Hageman factor) gene in hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:1286–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Hahn J, Bas M, Hoffmann TK, Greve J. Bradykinin-induced angioedema: definition, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis and therapy. HNO. 2015;63:885–893. doi: 10.1007/s00106-015-0084-8. quiz 894-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Cicardi M, Bellis P, Bertazzoni G, et al. Guidance for diagnosis and treatment of acute angioedema in the emergency department: consensus statement by a panel of Italian experts. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9:85–92. doi: 10.1007/s11739-013-0993-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.Worm M, Reese I, Ballmer-Weber B, et al. Leitlinie zum Management IgE-vermittelter Nahrungsmittelallergien. Allergo J Int. 2015;24 [Google Scholar]

- E7.Worm M, Eckermann O, Dolle S, et al. Triggers and treatment of anaphylaxis: an analysis of 4,000 cases from Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:367–375. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Ring J, Grosber M, Mohrenschlager M, Brockow K. Anaphylaxis: acute treatment and management. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2010;95:201–210. doi: 10.1159/000315953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Bork K, Maurer M, Bas M, et al. Leitlinie „Hereditäres Angioödem durch C1 Inhibitor Mangel“ 2012. AWMF-Register-Nr. 061-029 [Google Scholar]

- E10.Li HH, Moldovan D, Bernstein JA, et al. Recombinant human-C1 inhibitor is effective and safe for repeat hereditary angioedema attacks. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Craig TJ, Levy RJ, Wasserman RL, et al. Efficacy of human C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate compared with placebo in acute hereditary angioedema attacks. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Leibfried M, Kovary A. C1 esterase inhibitor (Berinert) for ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema: two case reports. J Pharm Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0897190016677427. pii: 0897190016677427 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Brockow K, et al. Classification and diagnosis of urticaria: German language version of the international S3-guideline. Allergo J. 2011;20:249–258. [Google Scholar]