Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to compare modelling approaches to estimate the individual survival benefit of treatment with either coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for patients with complex coronary artery disease.

Study Design and Setting

We estimated survival with Cox regression models that included the treatment variable (CABG/PCI) interacting with either an internally developed overall prognostic index or with individual prognostic factors. We analyzed data of patients who were randomized in the SYNTAX trial (1800 patients, 178 deaths).

Results

A negligible interaction with the prognostic index (p=0.51) led to 4-year survival estimates in favor of CABG for all patients. In contrast, individual interactions indicated substantial relative treatment effect heterogeneity (overall interaction p=0.004), and estimates of 4-year survival were numerically in favor of CABG for 1275 of 1800 patients (71%; 519 with 95% confidence). To test the more complex model with individual interactions we first employed penalized regression, resulting in smaller but largely consistent individual estimates of the survival difference between CABG and PCI. Second, strong treatment interactions were confirmed at external validation in 2891 patients from a multinational registry.

Conclusion

Modelling strategies that omit interactions may result in misleading estimates of absolute treatment benefit for individual patients with the potential hazard of suboptimal decision making.

Keywords: Treatment effect heterogeneity, Individualized treatment decisions, SYNTAX trial, Coronary artery bypass graft surgery, Percutaneous coronary intervention

Randomized clinical trials provide strong evidence of the benefits and harms of treatments. The estimated overall treatment effect is an important summary result of a clinical trial, but is insufficient to decide which treatment is best suited for an individual patient [1, 2]. Stratified medicine aims to make optimal treatment decisions for individual patients by predicting their response to treatment (treatment benefit) from baseline information. To make optimal decisions it has been suggested to compare absolute treatment benefit – the difference between relevant outcomes in treated and control groups (e.g. mortality reduction) – under different treatment strategies [3]. The absolute treatment benefit for individual patients depends on their risk, e.g. 1-year mortality in the absence of treatment (“baseline risk”) since patients at low risk have little to gain from treatment. The absolute benefit is often well estimated by assuming a constant relative risk reduction from a specific treatment. For example, when a treatment has a constant relative 1-year mortality reduction of 20% across patients, the absolute treatment benefit of a patient with 10% baseline mortality will be 2% (20%*10%), twice the absolute treatment benefit of 1% for a patient with 5% baseline mortality (20%*5%). In contrast heterogeneity in the relative risk reduction from a specific treatment (relative treatment effect heterogeneity) would make that absolute treatment effects differ for patients with equal baseline risk. For example, two patients with baseline risk of 10%, but different relative risk reductions of 10% and 20% show absolute risk reductions of 1% (10%*10%) or 2% (10%*20%), respectively [4].

Individual baseline risk can well be assessed with prognostic factors summarized in a prognostic index [5]. Relative treatment effect heterogeneity can be assessed following various approaches. One attractive option is to model a treatment interaction with the prognostic index that represents baseline risk [6–8]. This approach is more parsimonious than considering statistical interactions with each of the prognostic factors. The latter more flexible modelling approach might be reasonable if we expect that treatment response depends on one or more prognostic factors, e.g. because of different underlying biological mechanisms [4]. Such a factor may be referred to as a predictive factor for differential treatment effect [4] or treatment effect modifier [9]. Although modelling of treatment interactions has been recommended [10], it is sensitive to the pitfall of finding false-positive or false-negative subgroup effects [11–15].

We aimed to compare different modelling approaches to estimation of the absolute treatment effect for complex coronary artery disease (CAD) patients, who are treated with either coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). We consider relative treatment effect heterogeneity by modelling treatment interactions with a prognostic index and with individual prognostic factors. We specifically aimed to study how to assess the validity of using treatment interactions for guiding treatment decisions.

METHODS

Patient data

We analyzed data of 1800 patients with unprotected left main coronary artery (ULMCA) disease or de-novo three-vessel disease. Patients were randomized on a 1:1 basis to either CABG or PCI with first generation drug eluting stents in the Synergy between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00114972) [16, 17]. We used eight prognostic factors for mortality (Table 1; 178 deaths during 4 years of follow up) which were associated with mortality in either or in both treatment arms [18, 19]: SYNTAX score (www.syntaxscore.com [20, 21]), ULMCA disease, age, female gender, creatinine clearance, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), peripheral vascular disease (PVD) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). To complete a small number of missing prognostic factor values (SYNTAX score 0.6%; creatinine clearance 9.9%; LVEF 1.6%) we employed a multiple imputation strategy (5 imputations; aregImpute function in R package Hmisc [22, 23]). This strategy takes all aspects of uncertainty in the imputations into account by using the bootstrap for drawing predicted values from a full Bayesian predictive distribution.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients enrolled in the SYNTAX trial.

| Factor | Level | Patients | All-cause Death | Kaplan Meier 4-year survival (95% CI) | Univariable Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SYNTAX score | <23 | 573 | 47 | 91.4 (89.1,93.8) | 1.0 |

| 23–32 | 610 | 60 | 89.7 (87.3,92.2) | 1.2 (0.8,1.8) | |

| >=33 | 606 | 71 | 87.9 (85.2,90.5) | 1.5 (1.0,2.1) | |

| Age | <60 | 566 | 23 | 95.8 (94.1,97.5) | 1.0 |

| 61–69 | 595 | 53 | 90.8 (88.4,93.2) | 2.2 (1.4,3.7) | |

| >=70 | 639 | 102 | 83.2 (80.2,86.2) | 4.3 (2.7,6.7) | |

| Creatinine Clearance (mL/min) | <70 | 546 | 86 | 83.8 (80.7,87.0) | 1.0 |

| 71–94 | 546 | 38 | 92.8 (90.6,95.0) | 0.4 (0.3,0.6) | |

| >=94 | 546 | 35 | 93.4 (91.3,95.5) | 0.4 (0.3,0.6) | |

| LVEF (%) | <50 | 347 | 53 | 84.1 (80.2,88.1) | 1.0 |

| >=50 | 1425 | 123 | 91.0 (89.5,92.5) | 0.5 (0.4,0.7) | |

| ULMCA disease | no | 1095 | 101 | 90.3 (88.6,92.1) | 1.0 |

| yes | 705 | 77 | 88.7 (86.3,91.1) | 1.2 (0.9,1.6) | |

| Gender | female | 402 | 51 | 86.6 (83.2,90.1) | 1.0 |

| male | 1398 | 127 | 90.6 (89.0,92.1) | 0.7 (0.5,1.0) | |

| COPD | no | 1646 | 148 | 90.6 (89.2,92.1) | 1.0 |

| yes | 154 | 30 | 79.8 (73.6,86.6) | 2.4 (1.6,3.5) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | no | 1623 | 135 | 91.3 (89.9,92.7) | 1.0 |

| yes | 177 | 43 | 74.7 (68.5,81.6) | 3.3 (2.3,4.7) | |

| Treatment | CABG | 897 | 74 | 91.2 (89.3,93.1) | 1.0 |

| PCI | 903 | 104 | 88.3 (86.2,90.4) | 1.3 (1.0,1.8) |

Modelling of relative treatment effects

We employed Cox proportional hazards regression models (R package rms [22, 24]) to analyze the effects of the treatment and prognostic factors on all-cause mortality. First we fitted a model ignoring the treatment to define a prognostic index (PI) for mortality, regardless of the treatment [25]. The hazard function h(t) for a patient with prognostic factors xPF (SYNTAX score; ULMCA disease; age; female gender; creatinine clearance; LVEF; PVD; COPD) was modeled by the baseline hazard function h0(t) times the exponent of the linear predictor x′PFπPF. The effect of each prognostic factor on the log hazard is modeled by the parameters in πPF:

The prognostic performance of the PI was quantified by Harrell’s c-index [26].

Then we fitted 4 prognostic models. Model 1 contained only an overall treatment effect βT:

The parameter βT represents the relative increase in log hazard for treatment with PCI (xT = 1) versus treatment with CABG (xT = 0).

In model 2 we adjusted for the same prognostic factors xPF as in the prognostic index:

The resulting β̂T has been recommended as an efficient estimate of a constant relative treatment effect [27–29]. Model 2 allows for calculation of absolute risk predictions for individual patients, assuming a constant relative treatment effect across all patients.

Model 3 included the treatment (xT = 1 for PCI), the internally developed prognostic index (PI = x′PFπ̂PF) and their interaction xT PI:

The interaction effect estimate β̂T*PI expresses the heterogeneity in relative treatment effect for patients with different baseline risk [7].

Model 4 comprised the treatment (xT = 1 for PCI), the prognostic factors (xPF) and a treatment interaction xTxPF for each individual prognostic factor:

The interaction effect estimates in β̂T*PF express the difference – when comparing treatment with PCI (xT = 1) versus treatment with CABG (xT = 0) – in effect on the log hazard of each prognostic factor. The prognostic factors are each considered here as predictive of the relative treatment effect.

Confirmation of statistical interactions

Statistical significance of interactions in models 3 and 4 was quantified by the p-value of the overall likelihood ratio test statistic with 1 and 8 degrees of freedom respectively [30]. We used Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) to balance the goodness-of-fit of models 1–4 with their complexity[30].

To examine the sensitivity of the predicted most favorable treatment for overfitting of interaction effects, we employed Cox regression with an L2 (ridge) penalty [31, 32] in model 4 (R-package penalized [22, 33]). We compared penalized with unpenalized interaction effect estimates. Moreover, for each patient in the SYNTAX trial, we compared the most favorable treatment resulting from penalized regression versus that resulting from unpenalized regression.

To further assess the validity of the interaction effect estimates, an external validation study was done. We analyzed patients from the Drug Eluting stent for Left main coronary Artery disease (DELTA) Registry, a multinational, non-randomized, all-comers registry including 2891 patients with ULMCA disease [34]. We compared estimates of interaction effects in the DELTA registry with those in the SYNTAX trial.

Comparison of absolute treatment effects

Based on each of the 4 Cox regression models, we estimated individual patient absolute 4-year risk of all-cause mortality, both for CABG and PCI. We determined a confidence interval for the difference in individual PCI and CABG risk predictions by using the covariance matrix of the parameter estimates.

We assumed that the optimal treatment would be chosen based on the highest absolute treatment effect, expressed as difference in 4-year mortality. To assess the survival benefit of using one model over the other for such treatment decision making we employed a reclassification analysis. To estimate the survival benefit of one model over the other, we could use – for patients with a different treatment recommendation – either the predicted or the observed difference in 4-year mortality. We chose to use the observed mortality difference since it is less sensitive for overfitting of the models: individual risk estimates are used for determining the treatment recommendations, but not for estimating the mortality difference. We estimated the gain in survival by multiplying the proportion of patients with different treatment recommendations with their observed mortality difference in the randomized treatment (CABG and PCI) arms. These gains were also graphically shown in a “benefit graph”, as a visual representation of the reclassification analysis [35].

RESULTS

The prognostic index (hazard ratios in Table 2) well discriminated high-risk from low-risk patients (c-index 0.73). The variation in individual 4-year mortality predictions (IQR 4.4%–12.7%) implied substantial differences in absolute treatment effect, when the relative treatment effect was assumed constant across patients.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (95% CI) for: the prognostic index (combining the effect of all prognostic factors); models 1–4; model 4 with penalized regression; and external validation of model 4. Hazard ratios are presented for CABG (HRCABG) and PCI (HRPCI) separately since models 3 and 4 assume different prognostic effects for CABG and PCI. The interaction effects of the prognostic factors with the treatment are illustrated by HRPCI/HRCABG. AIC and degrees of freedom are listed for the prognostic index and model 1–4 for comparison of model adequacy.

| Prognostic index | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Penalized regression | External validation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCI vs CABG | 1.35 (1.00, 1.82) | 1.47 (1.08, 1.98) | 1.35 (0.93, 1.97) | 1.46 (0.99, 2.16) | 1.26 | 1.31 (0.97, 1.76) | |

| HRCABG | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| SYNTAX score (10 points) | 1.13 (1.00, 1.29) | 1.14 (1.01, 1.29) | 0.97 (0.79, 1.18) | 1.02 | 1.12 (0.95, 1.32) | ||

| Age (10 year) | 1.53 (1.23, 1.89) | 1.52 (1.23, 1.88) | 1.88 (1.34, 2.64) | 1.52 | 1.46 (1.15, 1.85) | ||

| Creatinine clearance (10 mL/min) | 0.86 (0.78, 0.96) | 0.86 (0.78, 0.95) | 0.91 (0.77, 1.07) | 0.89 | 0.91 (0.78, 1.06) | ||

| LVEF (10%) | 0.66 (0.54, 0.81) | 0.65 (0.53, 0.80) | 0.84 (0.61, 1.16) | 0.83 | 0.59 (0.47, 0.75) | ||

| ULMCA disease | 1.06 (0.79, 1.43) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.43) | 1.47 (0.93, 2.34) | 1.33 | |||

| Women | 1.13 (0.80, 1.58) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.57) | 0.59 (0.32, 1.10) | 0.75 | 0.52 (0.31, 0.87) | ||

| COPD | 1.87 (1.25, 2.79) | 1.87 (1.25, 2.79) | 2.84 (1.64, 4.90) | 2.46 | 3.63 (1.31, 10.04) | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2.55 (1.79, 3.63) | 2.64 (1.85, 3.76) | 2.79 (1.66, 4.71) | 2.53 | 1.37 (0.68, 2.79) | ||

| Prognostic index | 2.60 (2.05, 3.31) | ||||||

| HRPCI | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| SYNTAX score (10 points) | 1.13 (1.00, 1.29) | 1.14 (1.01, 1.29) | 1.27 (1.08, 1.50) | 1.24 | 1.32 (1.20, 1.46) | ||

| Age (10 year) | 1.53 (1.23, 1.89) | 1.52 (1.23, 1.88) | 1.29 (0.97, 1.71) | 1.34 | 1.34 (1.19, 1.52) | ||

| Creatinine clearance (10 mL/min) | 0.86 (0.78, 0.96) | 0.86 (0.78, 0.95) | 0.82 (0.72, 0.93) | 0.83 | 0.93 (0.86, 1.00) | ||

| LVEF (10%) | 0.66 (0.54, 0.81) | 0.65 (0.53, 0.80) | 0.56 (0.43, 0.73) | 0.56 | 0.57 (0.50, 0.65) | ||

| ULMCA disease | 1.06 (0.79, 1.43) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.43) | 0.82 (0.54, 1.23) | 0.86 | |||

| Women | 1.13 (0.80, 1.58) | 1.12 (0.79, 1.57) | 1.70 (1.11, 2.60) | 1.59 | 1.09 (0.82, 1.46) | ||

| COPD | 1.87 (1.25, 2.79) | 1.87 (1.25, 2.79) | 1.35 (0.74, 2.47) | 1.40 | 1.97 (0.88, 4.42) | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 2.55 (1.79, 3.63) | 2.64 (1.85, 3.76) | 2.79 (1.72, 4.53) | 2.78 | 1.77 (1.01, 3.09) | ||

| Prognostic index | 2.91 (2.33, 3.63) | ||||||

| HRPCI/HRCABG | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| SYNTAX score (10 points) | 1 | 1 | 1.32 (1.01, 1.71) | 1.22 | 1.18 (0.98, 1.42) | ||

| Age (10 year) | 1 | 1 | 0.69 (0.44, 1.07) | 0.88 | 0.92 (0.70, 1.21) | ||

| Creatinine clearance (10 mL/min) | 1 | 1 | 0.89 (0.73, 1.10) | 0.93 | 1.02 (0.86, 1.21) | ||

| LVEF (10%) | 1 | 1 | 0.67 (0.44, 1.00) | 0.68 | 0.96 (0.72, 1.27) | ||

| ULMCA disease | 1 | 1 | 0.56 (0.30, 1.03) | 0.65 | |||

| Women | 1 | 1 | 2.87 (1.35, 6.07) | 2.12 | 2.09 (1.16, 3.76) | ||

| COPD | 1 | 1 | 0.48 (0.21, 1.08) | 0.57 | 0.54 (0.20, 1.47) | ||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1 | 1 | 1.00 (0.49, 2.04) | 1.10 | 1.29 (0.51, 3.22) | ||

| Prognostic index | 1.12 (0.81, 1.55) | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| Degrees of freedom | 8 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 17 | ||

| AIC | 2516 | 2633 | 2511 | 2513 | 2504 | ||

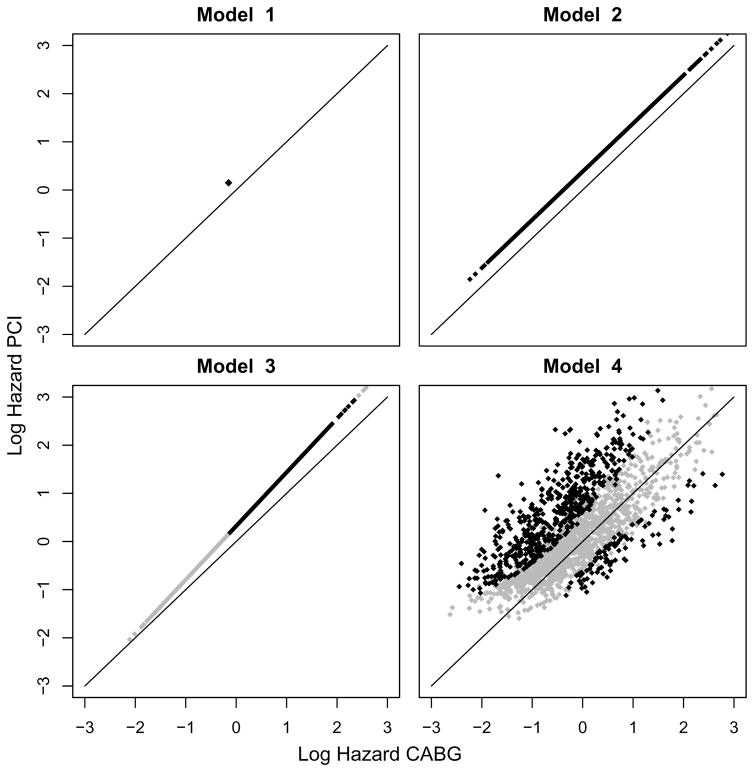

We visualized the results of models 1–4 with scatterplots of the predicted log hazards for CABG versus PCI (Figure 1). The overall treatment effect in model 1 was in favor of CABG (unadjusted HR [95% CI] for PCI vs. CABG 1.35 [1.00–1.82]; p-value 0.049; Table 2). Adjusting for prognostic factors in model 2 also led to an overall treatment effect in favor of CABG (adjusted HR [95% CI] for PCI vs. CABG 1.47 [1.08–1.98]; p-value 0.013; Table 2). The interaction of treatment with the prognostic index in model 3 was far from statistically significant (p-value 0.51), i.e. the relative treatment effect was hardly dependent on baseline risk (Table 2). Based on the predictions of model 3, CABG was favored for all 1800 patients. However, for 1003 patients the predictions were in favor of CABG with less than 95% confidence. Adding the flexibility of treatment interactions with each prognostic factor in model 4 showed substantial heterogeneity of relative treatment effect with a p-value of 0.004 for the overall interaction test based on 8 degrees of freedom. When balancing for model complexity, model 4 still showed the optimal adequacy with an AIC of 2504 against 2511 and 2513 for model 2 and 3 respectively (Table 2). Moderate to strong interactions were observed with SYNTAX score, age, LVEF, ULMCA disease, COPD, and female gender (interaction p<0.10). This more flexible model caused a major shift in the predicted most favorable treatment among the 1800 SYNTAX patients. Estimates of 4-year survival were in favor of PCI (PCI 91.4%; CABG 87.2%) for 525 patients (98 with 95% confidence) and in favor of CABG (CABG 93.0%; PCI 86.5%) for 1275 patients (519 with 95% confidence).

Figure 1.

When applying penalized regression to model 4, the interaction effect estimates were by definition shrunken, but the strongest interactions effects (SYNTAX score, age, LVEF, ULMCA disease, gender and COPD) remained substantial (Table 2). We visualized which treatment was favorable, i.e. had the lowest log hazard prediction according to the penalized regression model, split by patients for whom model 4 predicted favorable outcome with PCI (left panel of Figure 2) and for whom model 4 predicted favorable outcome with CABG (right panel of Figure 2). With penalized regression, 91.0% of the treatment recommendations for the 1800 patients were equal to model 4; All treatment recommendations were equal for the 617 patients for whom model 4 gave a recommendation with 95% confidence (black dots in Figure 2). A penalized regression analysis without penalties on the main effects, i.e. penalties on the interactions effects only, led to very similar treatment recommendations (results not shown). The effect estimates, particularly the strongest interaction effect estimates (SYNTAX score, gender and COPD), were similar in the DELTA registry (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The difference in survival benefit of using model 4 instead of model 3 for making treatment decisions can be derived from the benefit graph in Figure 3. The benefit graph visualizes for the combinations of treatment recommendation according to model 3 and model 4 (CABG/PCI; CABG/CABG), the proportion of patients (width of the bars) and the observed mortality (height of the bars) in both randomized treatment arms (PCI and CABG). For patients for whom both models recommended CABG, CABG (7.6% 4-year mortality) was more effective than PCI (13.7%), but for patients for whom model 4 recommended PCI, PCI (7.1%) was more effective than CABG (11.8%). We estimated a 1.4% survival benefit of using model 4 instead of model 3 by multiplication of the 29% of patients with a different treatment recommendation (total width of the first two bars in Figure 2) with their 4.7% observed difference in 4-year mortality between the randomized treatment arms (difference in height of the first two bars in Figure 2).

Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

We explored different modelling approaches for estimating heterogeneity in treatment effect across individual patients with complex CAD where CABG or PCI could be performed. Treatment interactions with each of the prognostic factors (model 4) fitted much better to the data compared to the treatment interaction with predicted prognosis as a single prognostic index (model 3). Penalized regression, specifically shrinking treatment interactions to the average treatment effect [31, 32] led to largely similar decisions for the individual patients, although relative risk differences – and consequently most absolute risk differences – between CABG and PCI predictions were smaller. These interactions were largely confirmed at external validation in the DELTA registry [19]. The major differences in expected treatment benefit for individual patients between models 3 and 4 (Figure 1), together with the survival benefit of using model 4 for making treatment decisions, indicated the importance of allowing for treatment interaction with each of the prognostic factors.

Our study confirms that prognostic effects may be very important for estimation of the individual benefit of treatment, since absolute treatment benefit will be higher for those at high risk when the relative risk reduction of a treatment is constant across patients [7, 25]. Furthermore, covariate adjustment may lead to an individualized and efficient treatment effect estimate [27–29]. We therefore recommend to always include prognostic factors when estimating treatment effects that should support decision making for individual patients.

The causal effect of treatment for an individual patient in our study is the difference between the outcome when the patient would have been treated with CABG and the outcome when the same patient would have been treated with PCI [36]. To estimate the difference in outcome when treatment choices are changed, we used randomized data from the all comers SYNTAX trial. In contrast, the use of observational data may produce biased treatment effect estimates when the variation between differently treated patients is not completely controlled for. Specifically, a recent study concluded that documented surgical ineligibility is common and associated with significantly increased long-term mortality among CAD patients undergoing PCI, even after adjustment for known risk factors [37].

We used an internally developed prognostic index for modelling the interaction of the treatment with baseline risk, because it will be relatively easy to obtain in future studies. Although an externally developed baseline risk score is attractive [25], it has been shown with simulations of randomized clinical trials that internally developed baseline risk scores – blinded to the treatment – produce relatively unbiased estimates of treatment effects across the spectrum of risk and are preferred to risk scores developed on the control population [38].

Although sub-group analysis based on interactions may be considered superior to classical sub-group analysis of single factors separately [10], it has similar pitfalls, such as a risk of false-positive findings if large numbers of interactions are assessed, and lack of power to detect interaction effects [11–15]. Similar to classical subgroup effect testing, our approach requires a clear biological motivation for differential mechanisms of treatment effects. In our study, more complex anatomy of the vessel makes PCI treatment a relatively less attractive treatment option. In other studies, when treatment modalities are less different or sample size is small, there may be less potential for predicting differential treatment effect. Ideally, the analysis of differential treatment effect focuses on confirming pre-specified interactions, but exploratory analyses of differential treatment effects could be considered if sample size is large. Exploratory analyses require even more emphasis on careful modelling strategies, model interpretation and model validation [5, 25, 32]. We focused on the overall significance of all interactions considered, similar to overall tests in prediction modelling [32]. We did not select interactions based on statistical significance of individual terms in the multivariable analysis, which might be considered as an alternative modelling approach.

We assumed that treatment decisions would be made on the basis of 4-year survival predictions. In clinical practice, a multidisciplinary heart team will also consider patient preferences, economic costs [39, 40] and other clinical outcomes – namely myocardial infarction, stroke and all-cause revascularization – compared to mortality alone.

In conclusion, this study illustrates that different modelling strategies may result in very different estimates of absolute treatment benefit for individual patients. Modelling treatment interactions with individual prognostic factors may be superior to a single interaction with a prognostic index to guide individualized decision making. Further validation and prospective evaluation of this approach across different settings is required.

WHAT IS NEW.

Key findings

Modelling treatment interactions with prognostic factors, rather than a constant relative treatment effect, caused a major shift in the predicted most favorable treatment among the SYNTAX trial patients.

The model with treatment interactions was supported by a better model fit, robustness in penalized regression analyses, and external validation.

What this adds to what was known

Although relative treatment effect is often considered to be constant in clinical trials, it may differ substantially across patients and influence the optimal choice of treatment for individual patients.

What is the implication, and what should change now

We recommend careful analysis of treatment interactions in clinical trial data to reveal possible relative treatment effect heterogeneity and to optimize individual treatment decision making.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all of the principal investigators of the SYNTAX trial and the DELTA trial for providing the data.

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (grant 917.11.383.) and the National Institutes of Health (grant U01 AA022802).

Authors’ contributions: David van Klaveren, Ewout Steyerberg, Yvonne Vergouwe, Patrick Serruys and Vasim Farooq designed the study and participated in the collection of data and organization of the databases from which this manuscript was developed. David van Klaveren and Yvonne Vergouwe analyzed the data and wrote the first draft of the paper. David van Klaveren, Ewout Steyerberg, Yvonne Vergouwe, Patrick Serruys and Vasim Farooq contributed to writing the paper and approved the final version.

Abbreviations

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft surgery

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- ULMCA disease

unprotected left main coronary artery disease

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- PVD

peripheral vascular disease

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- c-index

concordance-index

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rothwell PM. Can overall results of clinical trials be applied to all patients? Lancet. 1995;345:1616–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kravitz RL, Duan N, Braslow J. Evidence-based medicine, heterogeneity of treatment effects, and the trouble with averages. Milbank Q. 2004;82:661–87. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00327.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothwell PM, Mehta Z, Howard SC, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP. Treating individuals 3: from subgroups to individuals: general principles and the example of carotid endarterectomy. Lancet. 2005;365:256–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hingorani AD, Windt DA, Riley RD, Abrams K, Moons KG, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 4: stratified medicine research. BMJ. 2013;346:e5793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steyerberg EW. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayward AC, Goldsmith K, Johnson AM Surveillance Subgroup of S. Report of the Specialist Advisory Committee on Antimicrobial Resistance (SACAR) Surveillance Subgroup. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(Suppl 1):i33–42. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kent DM, Hayward RA. Limitations of applying summary results of clinical trials to individual patients: the need for risk stratification. JAMA. 2007;298:1209–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pocock SJ, Lubsen J. More on subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2076. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0800616. author reply -7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayward RA, Kent DM, Vijan S, Hofer TP. Multivariable risk prediction can greatly enhance the statistical power of clinical trial subgroup analysis. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Assmann SF, Pocock SJ, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis and other (mis)uses of baseline data in clinical trials. Lancet. 2000;355:1064–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez AV, Boersma E, Murray GD, Habbema JD, Steyerberg EW. Subgroup analyses in therapeutic cardiovascular clinical trials: are most of them misleading? Am Heart J. 2006;151:257–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine--reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2189–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr077003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brookes ST, Whitely E, Egger M, Smith GD, Mulheran PA, Peters TJ. Subgroup analyses in randomized trials: risks of subgroup-specific analyses; power and sample size for the interaction test. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmidt AF, Groenwold RH, Knol MJ, Hoes AW, Nielen M, Roes KC, et al. Exploring interaction effects in small samples increases rates of false-positive and false-negative findings: results from a systematic review and simulation study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:821–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong AT, Serruys PW, Mohr FW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Holmes DR, Jr, et al. The SYNergy between percutaneous coronary intervention with TAXus and cardiac surgery (SYNTAX) study: design, rationale, and run-in phase. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farooq V, Vergouwe Y, Raber L, Vranckx P, Garcia-Garcia H, Diletti R, et al. Combined anatomical and clinical factors for the long-term risk stratification of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the Logistic Clinical SYNTAX score. European heart journal. 2012;33:3098–104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farooq V, van Klaveren D, Steyerberg EW, Meliga E, Vergouwe Y, Chieffo A, et al. Anatomical and clinical characteristics to guide decision making between coronary artery bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention for individual patients: development and validation of SYNTAX score II. Lancet. 2013;381:639–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.SYNTAX score calculator. SYNTAX working-group; www.syntaxscore.com. Launched 19th May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sianos G, Morel MA, APK, Morice MC, Colombo A, Dawkins K, et al. The SYNTAX Score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2005:219–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2011. URL http://www.R-project.org/. 3-900051-07-0 ed. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrell FE., Jr Hmisc: Harrell Miscellaneous. R package version 3.9-2. 2012 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=Hmisc.

- 24.Harrell FE., Jr rms: Regression Modeling Strategies. R package version 3.4-0. 2012 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rms.

- 25.Kent DM, Rothwell PM, Ioannidis JP, Altman DG, Hayward RA. Assessing and reporting heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials: a proposal. Trials. 2010;11:85. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrell FE, Jr, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247:2543–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hauck WW, Anderson S, Marcus SM. Should we adjust for covariates in nonlinear regression analyses of randomized trials? Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:249–56. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steyerberg EW, Bossuyt PM, Lee KL. Clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction: should we adjust for baseline characteristics? Am Heart J. 2000;139:745–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernandez AV, Eijkemans MJ, Steyerberg EW. Randomized controlled trials with time-to-event outcomes: how much does prespecified covariate adjustment increase power? Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verweij PJ, Van Houwelingen HC. Penalized likelihood in Cox regression. Stat Med. 1994;13:2427–36. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780132307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrell FE, Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1996;15:361–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goeman JJ. penalized: L1 (lasso and fused lasso) and L2 (ridge) penalized estimation in GLMs and in the Cox model. R package, version 0.9-42. 2012 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=penalized.

- 34.Chieffo A, Meliga E, Latib A, Park SJ, Onuma Y, Capranzano P, et al. Drug-eluting stent for left main coronary artery disease. The DELTA registry: a multicenter registry evaluating percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting for left main treatment. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:718–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steyerberg EW, Vedder MM, Leening MJ, Postmus D, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Van Calster B, et al. Graphical assessment of incremental value of novel markers in prediction models: From statistical to decision analytical perspectives. Biom J. 2014 doi: 10.1002/bimj.201300260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1974;66:688–701. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldo SW, Secemsky EA, O’Brien C, Kennedy KF, Pomerantsev E, Sundt TM, et al. Surgical Ineligibility and Mortality Among Patients with Unprotected Left Main or Multivessel Coronary Artery Disease Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circulation. 2014 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burke JF, Hayward RA, Nelson JP, Kent DM. Using internally developed risk models to assess heterogeneity in treatment effects in clinical trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:163–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen DJ, Lavelle TA, Van Hout B, Li H, Lei Y, Robertus K, et al. Economic outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents versus bypass surgery for patients with left main or three-vessel coronary artery disease: one-year results from the SYNTAX trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;79:198–209. doi: 10.1002/ccd.23147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magnuson EA, Farkouh ME, Fuster V, Wang K, Vilain K, Li H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention with drug eluting stents versus bypass surgery for patients with diabetes mellitus and multivessel coronary artery disease: results from the FREEDOM trial. Circulation. 2013;127:820–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.147488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]