Abstract

Purpose

The objectives of this review are to summarize the current practices and major recent advances in critical care nutrition and metabolism, review common beliefs that have been contradicted by recent trials, highlight key remaining areas of uncertainty, and suggest recommendations for the top 10 studies/trials to be done in the next 10 years.

Methods

Recent literature was reviewed and developments and knowledge gaps were summarized. The panel identified candidate topics for future trials in critical care nutrition and metabolism. Then, members of the panel rated each one of the topics using a grading system (0–4). Potential studies were ranked on the basis of average score.

Results

Recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have challenged several concepts, including the notion that energy expenditure must be met universally in all critically ill patients during the acute phase of critical illness, the routine monitoring of gastric residual volume, and the value of immune-modulating nutrition. The optimal protein dose combined with standardized active and passive mobilization during the acute phase and post-acute phase of critical illness were the top ranked studies for the next 10 years. Nutritional assessment, nutritional strategies in critically obese patients, and the effects of continuous versus intermittent enteral nutrition were also among the highest-ranking studies.

Conclusions

Priorities for clinical research in the field of nutritional management of critically ill patients were suggested, with the prospect that different nutritional interventions targeted to the appropriate patient population will be examined for their effect on facilitating recovery and improving survival in adequately powered and properly designed studies, probably in conjunction with physical activity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00134-017-4711-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Nutrition, Metabolism, Critical care, Intensive care, Protein, Calorie

Introduction

The last decade has seen much needed increases in the number of methodologically sound studies in the field of nutrition therapy of the critically ill, adding to the expanding body of knowledge and highlighting or inducing many uncertainties and controversies [1]. In this review of the research agenda for intensive care medicine nutrition and metabolism in adults, we summarize the current practices, major recent advances in the field, and common beliefs that have been contradicted by recent trials. We then highlight key remaining areas of uncertainty and suggest recommendations for the top 10 studies/trials to be done in the next 10 years.

Current standard of care

Recent randomized clinical trials have questioned several previously accepted but poorly supported concepts in nutrition therapy of critically ill patients. Based on the current available evidence, defining a universally accepted standard of care is difficult. Existing clinical practice guidelines by different societies/organizations have provided detailed evidence-based assessment of available evidence. Although the resulting recommendations have similarities, significant differences exist that reflect lower levels of evidence and differences in the methodology of guideline development [2]. In practice, considerable variations also exist. The use of routes of nutrition [enteral nutrition (EN) or parenteral nutrition (PN)] and the dose of calories and protein all vary across centers and countries (Supplemental References). For the evaluation of energy expenditure (EE), different predictive equations are used. Indirect calorimetry is infrequently used, reflecting the limited supportive evidence, the limited availability, and the difficulties in performing and interpreting the measurement in critically ill patients (Fig. 1) [3, 4].

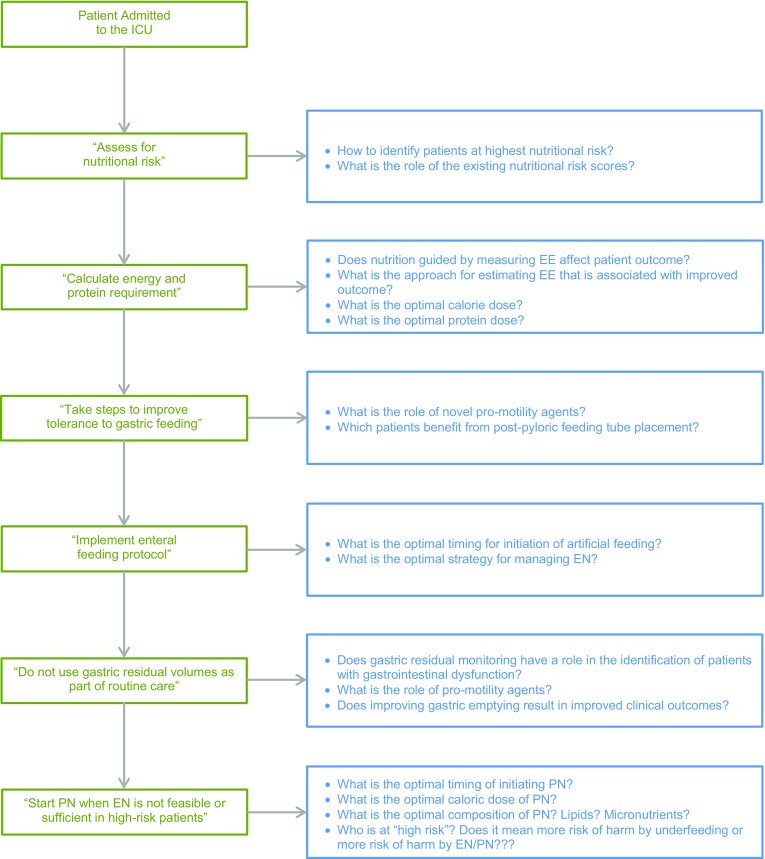

Fig. 1.

Flowchart highlighting some of the uncertainties in the nutritional support decision-making. The boxes on the left are based on the “bundle statements” from the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutritional Support therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient [5]. The boxes on the right represent corresponding areas of uncertainties

Major recent advances and common beliefs that have been contradicted by recent trials

Provision of early EN and PN

The value of early initiation of EN is supported by physiologic data. Over the first week of ICU admission, most critically ill patients experience the non-nutritional benefits of EN by virtue of the gastrointestinal responses [maintaining gut integrity, supporting the diversity of the microbiome, and sustaining gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and secretory IgA production], immune responses [sustaining mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) at distant sites, stimulating Th2 anti-inflammatory lymphocytes and T-regulatory cells], and metabolic responses [increasing incretin release, and reducing generation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs)] (Supplementary References). Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrate that early EN is associated with reduction in mortality and infections compared to withholding early EN, although the included individual clinical trials are heterogeneous and not adequately powered [5]. Additionally, the definition of early nutrition remains arbitrary and has ranged from 3 to 7 days in different interventional studies. Nevertheless, the notion that EE must be met universally in all ICU patients during the acute phase of critical illness has been challenged. Indeed, a number of trials in general ICU patients and in selected populations (acute respiratory failure, acute lung injury, refeeding syndrome) show that restricted feeding strategies described as “permissive or trophic” during the early phase of critical illness result in similar outcomes compared with standard caloric intake (Table 1) [6–10]. However, “standard” caloric intake in these trials met only 70–80% of EE. The protein intakes also differed between the study arms in most studies [6, 7], but not all [8]. So it remains uncertain whether the provision of energy to fully match EE has clinical benefit.

Table 1.

Selected RCTs that are listed in the article

| Study | Population | Number of patients | Intervention/control | Main findings | Trial title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EDEN [7] | Patients with acute lung injury requiring mechanical ventilation | 1000 | Trophic enteral feeding (10 ml/h,10–20 kcal/h) compared to full enteral feeding |

No difference in ventilator-free days, 60-day mortality, or infectious complications | Early versus delayed enteral feeding to treat people with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| PermiT [8] | Critically ill patients | 894 | Permissive underfeeding (40–60% of calculated caloric requirements) compared to standard enteral feeding (70–100%) | No difference in 90-day mortality | Permissive underfeeding versus target enteral feeding in adult critically ill patients |

| EPaNIC [11] | Critically ill adults in whom caloric targets cannot be met by enteral nutrition alone | 4640 | Early PN (initiated within 48 h after ICU admission) compared to late PN (not initiated before day 8) | Late initiation of parenteral nutrition was associated with faster recovery and fewer complications, as compared with early initiation | Impact of early parenteral nutrition completing enteral nutrition in adult critically ill patients |

| PEPaNIC [12] | Critically ill children with an expected stay of 24 h or more in the ICU and a medium malnutrition risk (using score the Screening Tool for Risk on Nutritional Status and Growth—STRONGkids score) | 1440 | Early PN (initiated within 24 h after ICU admission) compared to late PN (not initiated until day 8) | Late PN was associated with similar mortality, but less infections, shorter ICU stay, and higher likelihood of an earlier live discharge from the ICU | Impact of early parenteral nutrition completing enteral nutrition in pediatric critically ill patients |

| Early PN [13] | Critically ill adults with relative contraindications to early EN | 1372 | Early PN (within 24 h of ICU admission) compared to standard care | No difference in 60-day mortality. Early PN strategy resulted in fewer days of invasive ventilation but not significantly shorter ICU or hospital stays | Early parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients with short-term relative contraindications to early enteral nutrition |

| Impact of SPN on infection rate, duration of mechanical ventilation & rehabilitation in ICU patients [14] | Patients who received less than 60% of EE from EN at ICU day 3 | 305 | EN alone compared to EN with supplemental PN | Supplemental PN was associated with a decrease of late infections compared to EN alone | |

| CALORIES [16] | Patients who could be fed through either the parenteral or the enteral route | 2388 | Early EN compared to early PN for the first 5 days | No difference in 30-day mortality | Trial of the route of early nutritional support in critically ill adults |

| REGANE [26] | Adults requiring invasive mechanical ventilation | 322 | Intervention group (GRV = 500 ml) compared to control group (GRV = 200 ml) | No difference in diet volume ratio (diet received/diet prescribed), and pneumonia | Gastric residual volume during enteral nutrition in ICU patients |

| NUTRIREA1 [25] | Adults requiring invasive mechanical ventilation | 452 | No routine monitoring of GRV compared to routine monitoring | No difference in pneumonia | Study of impact of not measuring residual gastric volume on nosocomial pneumonia rates |

| REDOXS [29] | Mechanically ventilated patients with multiorgan failure | 1223 | 2-by-2 factorial trial, patients were randomized to receive supplements of glutamine, antioxidants, both, or placebo | Early provision of glutamine or antioxidants did not improve clinical outcomes, and glutamine was associated with an increase in mortality among critically ill patients with multiorgan failure | Reducing deaths due to oxidative Stress |

| OMEGA trial [30] | Patients with acute lung injury requiring mechanical ventilation | 272 | Enteral supplementation of n-3 fatty acids, γ-linolenic acid, and antioxidants compared to placebo | Supplementation of n-3 fatty acids, γ-linolenic acid, and antioxidants did not improve the primary endpoint of ventilator-free days or other clinical outcomes and might be harmful | Early versus delayed enteral feeding and omega-3 fatty acid/antioxidant supplementation for treating people with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome (The EDEN-omega study) (EDEN-Omega) |

| MetaPlus [31] | Mechanically ventilated critically ill patients | 301 | High-protein EN enriched with glutamine, omega-3 fatty acids, selenium, and antioxidants compared to standard high-protein EN | The intervention did not reduce infectious complications or improve other clinical endpoints and may have been harmful as suggested by an increased adjusted 6-month mortality | High-protein enteral nutrition enriched with immune-modulating nutrients vs standard high-protein enteral nutrition and nosocomial infections in the ICU |

GRV gastric residual volume

Along with the lack of benefit of early aggressive EN, the use of supplemental PN in the first week to achieve caloric targets for all patients has now been challenged. The EPaNIC study, conducted in critically ill adults in whom caloric targets could not be met by EN alone, showed that late initiation of PN (i.e., after a week of critical illness) was associated with faster recovery and fewer complications, as compared with early initiation [11]. Interestingly, the similarly designed PEPaNIC trial in critically ill children showed similar results [12]. The Early PN trial found that early PN (i.e., within the first hours of admission in ICU) to critically ill adults with relative contraindications to early EN was not associated with a significant clinical benefit [13]. Another study enrolled patients who received less than 60% of EE from EN at ICU day 3 and found that supplemental PN was associated with a decrease of late infections compared to EN alone [14]. Of note, common infections, including pneumonia and bloodstream infections, did not decrease [14]. While these studies are somewhat conflicting, it would appear that there is no benefit in providing nutrition parenterally early in the ICU stay.

The underlying mechanisms and potential consequences of an increased provision of nutrients during the early phase of critical illness are currently investigated. A pre-planned secondary analysis of 600 patients included in the EPaNIC trial, with prospective assessment of functional weakness, revealed that tolerating a substantial macronutrient deficit during the first week of critical illness reduced ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW). In addition, muscle biopsies indicated that activation of autophagy might explain the protective effect on weakness of delaying PN delivery [15]. Hyperglycemia during feeding may occur since the endogenous production of glucose cannot be fully inhibited by exogenous caloric supply [3]. Nutrient delivery may lead to the development of refeeding syndrome or may counteract potentially adaptive early anorectic response of severe illness, particularly in severely ill patients, identified by high “nutritional risk” as discussed below. Irrespective of the underlying mechanisms, the optimal amount of calories and proteins in the early phase of critical illness remains unknown.

Route of early feeding

The CALORIES trial was a pragmatic RCT that compared early EN to early PN for the first 5 days in an unselected critically ill population. The majority of patients in both arms did not reach EE targets and no difference on short-term outcome was found [16]. A recent meta-analysis that included the results of the CALORIES trial comparing EN to PN found no effect on overall mortality [17]. However, EN was associated with lower infective complications and shorter ICU length of stay (LOS) [17].

Nutritional risk assessment

It has been generally accepted that a small percentage of patients, those at highest nutritional risk, may require the nutritional benefits of therapy where full macro- and micronutrient provision maximizes protein synthesis, supports lean body mass, and corrects nutrient deficiencies. Hence, there has been increasing work to define nutritional risk assessment in nutrition therapy [18]. The NUTRIC (The Nutrition Risk in Critically ill) score was proposed to identify those who will benefit the most from nutrition therapy or be harmed the most by ongoing inattention to nutrition. The clinical utility of this score has been examined in three multi-institutional databases. These studies demonstrate that patients with high NUTRIC scores have reduced mortality with increased nutrition intake compared to patients with low NUTRIC scores where no such relationship between intake and mortality exists [18, 19]. Of note, the variables included in this score mainly reflect the severity of disease and are not direct measures of nutritional status. A post hoc analysis of the PermiT trial showed that permissive underfeeding was associated with similar mortality compared with standard feeding in patients with high and low nutritional risk as assessed by the NUTRIC score and several other nutritional risk tools [20]. Other scores have also been developed, such as the Nutrition Risk Screening-2002 (NRS-2002) score and the Patient- And Nutrition-Derived Outcome Risk Assessment Score (PANDORA); the latter has yet to be validated in the critically ill population [21, 22]. The role of nutritional assessment using an objective measurement of body composition or more specifically muscle mass (using CT, ultrasound, or bioelectric impedance) requires further study (Supplementary References). Although these parameters identify increased risk of death, it is unclear if these are modifiable by nutrition or if they just reflect disease severity.

The uncertainty about the optimal approach for nutritional assessment is further complicated by the controversy regarding whether patients with severe undernutrition would benefit or alternatively suffer from high energy and protein intakes. In patients with hypophosphatemia within 72 h of initiation of nutrition, restricted versus standard caloric intake resulted in no difference in the primary endpoint of the number of days alive after ICU discharge, but with more patients alive at day 60 [23]. Post hoc analysis of the PermiT trial suggested that patients with low prealbumin levels might have better outcomes with restricted calories [20]. Post hoc analysis of the EPaNIC trial showed that the beneficial effect of a delay in the initiation of PN was generalized across different strata of severity of illness including those who were most severely ill [24]. Interestingly, the PEPaNIC trial showed that early PN provoked more harm in children at increased nutritional risk according to their Screening Tool for Risk on Nutritional Status and Growth (STRONGkids) score [12].

Another aspect of nutritional assessment is how to differentiate the acute (catabolic) phase and the post-acute (anabolic) phase. There is a need for a dynamic marker to identify patients “readiness for enhanced feeding”. Such a marker would allow an adaptation of the nutritional strategy to the clinical evolution based on endocrinological or metabolic signals rather than starting enhanced energy/protein intake at a predefined number of days.

Gastric residual volume (GRV)

The role of GRV measurement to monitor tolerance of patients on EN has been challenged. Although GRVs are generally considered to indicate gastric emptying rate, volumes aspirated are also affected by the rate of feed administration, the technique of aspiration, gastric secretion, and duodeno-gastric reflux. Increasing the limit of monitored GRV from 200 to 500 ml (REGANE study) or adopting a no routine monitoring of GRV strategy (NUTRIREA1 study) among adults requiring mechanical ventilation did not increase pneumonia [25, 26]. However, these studies included predominately patients admitted for medical (as opposed to surgical) reasons and were underpowered to assess the impact on other clinical outcomes. In one study, a 24-h total GRV of greater than 250 ml was shown to predict slow gastric emptying, but the sensitivity and negative predictive value were modest [27].

Immune-modulating nutrition

The use of immune-modulating macronutrients (e.g., glutamine, arginine, and omega-3 fatty acids) and micronutrients (e.g., antioxidant vitamins A, C, and E and the minerals selenium and zinc) used alone (pharmaconutrition) or in combination (immunonutrition) to enrich EN or PN and improve outcomes of ICU patients has been challenged in a number of RCTs [28]. The REDOXS trial showed an increase in mortality with high doses of enteral and parenteral glutamine (0.6 g/kg per day) [29]. The OMEGA trial showed that enteral supplementation of n-3 fatty acids, γ-linolenic acid, and antioxidants in patients with acute lung injury did not improve the primary endpoint of ventilator-free days or other clinical outcomes and might be harmful [30]. In the MetaPlus study, high-protein EN enriched with glutamine, omega-3 fatty acids, selenium, and antioxidants did not reduce infectious complications or improve other clinical endpoints when compared to standard high-protein EN and may have been harmful as suggested by an increased adjusted 6-month mortality [31]. A recent meta-analysis showed that enteral glutamine supplementation does not confer clinical benefit in critically ill patients [32]. However, in severe burn patients, enteral glutamine supplementation was associated with reduction in hospital mortality and stay [32].

The danger of providing arginine in the setting of sepsis has been challenged, as multiple studies in septic patients showed no adverse hemodynamic changes in response to intravenous arginine infusion [33]. The use of arginine/fish oil formulas may still be beneficial in elective surgical patients, as its use has been shown in four recent meta-analyses to reduce infection and hospital LOS and improve other clinical outcomes (Supplementary References). In severe acute pancreatitis, three small studies in immune-modulating nutrition of varying components showed improved outcomes, but the small numbers enrolled were such that only one reached significance and a meta-analysis was negative (Supplementary References). This last group of patients (severe acute pancreatitis) should be studied further before discounting immune-modulating nutrition across the board. Important questions regarding immune-modulating nutrition remain (Table 1).

Glucose control

The survival benefit of tight glucose control (TGC) (target 4.4–6.1 mmol/L) observed in an RCT of predominantly (cardiac) surgical patients and an RCT of medical ICU patients [34, 35] could not be reproduced in other RCTs [36]. The largest trial, NICE-SUGAR, showed increased 90-day mortality with TGC compared to a target of less than 10 mmol/L [37]. The observed differences in outcome may be related to different targets achieved, different blood glucose analyzing methodology, or the difference in the amount and route of early nutritional intake between the Leuven as compared to the other trials [36, 38]. After 15 years of intense research in this field, a few assertions are widely accepted: (1) there are three domains of dysglycemia (severe hyperglycemia, moderate hypoglycemia, and high glycemic variability) which are individually and synergistically associated with poor vital outcome; (2) blood glucose control is demanding, difficult to perform, and requires technological improvements in monitoring and therapeutic modalities including automated algorithms and new agents such as long-acting insulin or glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists; (3) the optimal target could differ over time and according to the pre-existence of diabetes and its control. A study found that markers of inflammation, endothelial injury, and coagulation activation were attenuated in the patients with stress hyperglycemia without diabetes but not in diabetics, suggesting different underlying pathophysiology. In a large observational study, reduced mortality was observed with blood glucose between 80 and 140 mg/dl in non-diabetic patients and 110–180 mg/dl in diabetic patients (Supplementary References). These hypothesis-generating findings are yet to be examined in RCTs.

Remaining areas of uncertainty

As indicated above, recent trials have highlighted many areas of uncertainty in critical care nutrition. We highlight selected areas here and in Table 2.

Table 2.

Remaining areas of uncertainty in nutrition of critically ill patients

| 1. Evaluation of energy expenditure and monitoring of nutritional effects in different phases of critical illness and across patients with different nutritional risks |

| 1.1 Does nutrition guided by measuring energy expenditure affect patient outcome as compared to estimated energy expenditure (EE) by predictive equations? 1.2 What is the approach for estimating EE that is associated with improved outcomes? 1.3 What is the most appropriate energy target expressed as a proportion of (time-dependent) EE and should energy intake match the EE? 1.4 How to assess the burden/beneficial effect of feeding on metabolism and cellular integrity in a clinically useful, continuous point of care measurement monitoring? 1.5 Is there a role for biomarkers in monitoring feeding? 1.6 How to identify patients at highest nutritional risk in its acute and chronic components? 1.7 Does nutrition risk assessment alter the timing of initiation, rate of increase, or ultimate goals of nutrition therapy? 1.8 What is the role of existing nutritional risk scores including nutritional and non-nutritional variables (e.g., NRS-2002 or combination of NUTRIC + PANDORA?) [21] 1.9 How to define and monitor for refeeding syndrome and what is the optimal caloric and protein intake in these patients? |

| 2. Method of administration of enteral and parenteral nutrition |

| 2.1 What is the optimal timing for initiation of artificial feeding? 2.2 What is the optimal strategy for management for enteral feeding? 2.3 How should feeding strategy vary at different stages of critical illness and recovery? 2.4 What is the effect of continuous feeding vs intermittent feeding on protein synthesis and on patient-centered outcomes? 2.5 What is the role of alternative lipid emulsions in PN? |

| 3. Substrate requirements: proteins, carbohydrates, and micronutrients |

| 3.1 What is optimal protein dose to facilitate recovery of critically ill patients in general and nutritionally high-risk patients in particular (mortality and physical function) and does it need to be combined with some sort of muscle use/exercise? 3.2 Is there any interrelationship between calorie and protein “dose”? 3.3 What is the amount of substrate that is actually absorbed in critically ill patients given gut dysfunction and malabsorption? 3.4 What is the role of whey-based protein (high in leucine) in muscle synthesis and facilitating recovery from critical illness? 3.5 What combinations of amino acids are optimal: should they mimic “normal” intake or be aimed at inducing metabolism or supporting host defense? 3.6 What is the role of small peptide vs polymeric formulae in patients at high risk of intolerance? 3.7 What is the appropriate amount of micronutrients to be provided in ICU patients? |

| 4. Nutrition and functional recovery |

| 4.1 What is the best way to measure the effect of nutrition on physical recovery outcomes of survivors of ICU? 4.2 Is there a role for bedside measures to monitor the impact of feeding practices on muscle (such as blood, urine, or muscle imaging) and how to correlate these measures with long-term functional and vital outcomes? 4.3 What is the effect of combination of ranges of proteins + physical activity + monitoring of muscle mass/function? |

| 5. Management of intestinal and gastric feeding intolerance |

| 5.1 What is the role of novel pro-motility agents? 5.2 Does the acceleration of gastric emptying to increase nutrient delivery to the small intestine during gastric feeding result in improved clinical outcomes? 5.3 What is the association between small bowel feeding and non-occlusive bowel disease/necrosis? |

| 6. Immune-modulating nutrition |

| 6.1 What is the role of glutamine in glutamine-deficient patients and conditions (like burn-injured patients)? 6.2 What is the role of moderate-dose glutamine in patients receiving exclusive PN after the first week in ICU and in absence of renal or hepatic failure? 6.3 What is the role of high-dose IV selenium in cardiac surgery patients? 6.4 What is the role of high-dose IV fish oils in inflammatory conditions, like sepsis and cardiac surgery? 6.5 What is the role of high-dose zinc supplementation in critically ill adults? 6.6 What is the role of vitamin D supplementation in critically ill patients? 6.7 Is there a role of pharmacological agents in promoting retention of muscle mass and improved physical outcomes (e.g., growth hormone, ghrelin agonists, anabolic steroids, and others)? 6.8 Is there a role for arginine/fish oil formula in severe acute pancreatitis? 6.9 Should pharmaconutrition be used alone or in combination with other EN or PN? 6.10 What is the effect of timing of immune-modulating nutrition: pre ICU, early, late etc.? 6.11 How does the effect of immune-modulating nutrition relate to the actual immune status? |

| 7. Glucose control |

| 7.1 Should glucose targets differ by diabetic status? Should glucose targets differ according to previous glycemic control in patients with pre-existing diabetes? 7.2 What are the prospects for precision glycemic control? 7.3 Should glucose control differ by feeding strategy and by glucose measurement strategy? 7.4 What is the role of insulin glargine in glucose control in critically ill patients? 7.5 What is role for GLP-1 and its agonists in blood glucose control during critical illness? 7.6 What is the optimal strategy to control blood glucose with avoidance of hypoglycemia and glycemic fluctuations? |

Evaluation of EE and monitoring of nutritional effects in different phases of critical illness and across patients with different nutritional risks

Indirect calorimetry is considered the gold standard in measuring EE in clinical settings [39] and is recommended, when available, by clinical practice guidelines, although it is acknowledged that the evidence on which this premise is based is limited [5, 40]. Indirect calorimetry measurements of EE are generally performed during 1–2 h per day and under controlled conditions and therefore do not account for the variation of EE during 24 h. Nevertheless, measuring EE might have a role in preventing overfeeding. Predictive equations are often used instead of direct EE measurement but may over- or underestimate EE and do not account for the variation of EE during critical illness over time [3]. As in clinical practice, most major studies including targeted feeding in the design rely on these predicted values of EE. A more fundamental question is whether calories delivered to patients during the acute phase of their critical illness should match measured or estimated EE despite ongoing endogenous nutrient release, which is not suppressed by feeding and is unmeasurable [41]. Other important questions remain on to how to assess nutritional risk and how to to determine which patient groups benefit from specific nutritional interventions and which do not or experience harm (Table 2)

Method of administration of EN

The approach of continuous feeding has been challenged as being unphysiologic [42]. In animal models and in healthy volunteers, data suggest that protein synthesis is significantly greater after the consumption of a single bolus dose of whey protein than when the whey protein was given as small-pulsed drinks or as a continuous infusion [42–44]. Intermittent feeding may also have greater anabolic response, increased gastric contractility and emptying, as well as less diarrhea and better absorption owing to slowing of intestinal transit from increased peptide YY release [45, 46]. However, clinical data supporting this practice are awaited.

Substrate requirements: proteins and carbohydrates

It remains unclear what constitutes an optimal protein “dose” to facilitate recovery of nutritionally high-risk patients. Current recommendations are based on very limited evidence. In one trial, a daily intravenous supplement of standard amino acids did not alter the duration of renal dysfunction, and functional outcome at 90 days was unaffected by the large difference in dose of amino acids (0.5–1 kg over 1 week) [47]. In another study, the administration of amino acids at either 0.8 or 1.2 g/kg in patients receiving PN did not result in a difference in the primary endpoint of handgrip at ICU discharge, although it resulted in slight improvements in other functional outcomes and in nitrogen balance [48]. The interpretation of these improvements was somewhat complicated by the higher mortality (potentially competing with weakness) in the patients receiving more amino acids [49].

Another issue to consider is whether there is any interrelationship between calorie and protein “dose”. There is evidence to suggest that if a basal amount of protein is provided, varying the percentage of goal calories delivered may not change outcome. In the PermiT trial [8] and other studies [50], restricting calories did not change outcome compared to full feeds when protein provision was equal between groups. On the other hand, data from the International Nutrition Survey 2013 showed that achieving at least 80% of prescribed protein intake (but not energy intake) was associated with increased survival in ICU patients [51]. Another study showed increased survival with achievement of protein intake of 1.2 g/kg body weight when patients were not overfed with energy (more than 110% of measured EE) [52]. An earlier small RCT showed that higher protein delivery at 1.4 gm/kg/day (and reduced calories, 12 kcal/kg) led to better outcome (reduced SOFA score at 48 h) than lower protein doses at 0.76 gm/kg/day (and reduced calories, 14 kcal/kg) [53].

Not all proteins are equivalent in their ability to stimulate protein synthesis; whey protein (high in leucine) may increase muscle synthesis compared to soy or casein protein [42]. An RCT in obese older adults showed that a high whey protein-, leucine-, and vitamin D-enriched supplement compared with isocaloric control preserves appendicular muscle mass during hypocaloric feeding and resistance exercise program [54]. The implications for critically ill patients are unknown and require further study.

While many different combinations of amino acids are theoretically possible, it remains unclear whether these combinations should mimic “normal” intake or be aimed at inducing metabolism or supporting host defense. In contrast to lipids or glucose, an individual amino acid given in excess of demands cannot be simply stored and needs to be metabolized, thereby consuming other amino acids [15, 55].

Protein and functional recovery

Long-term functional recovery of some ICU patients is markedly impaired, e.g., patients with severe ARDS only achieve 76% of a reference value on 6-min walk test for up to 5 years [56]. The relationship between ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) and delayed functional recovery is only partially established and it is unclear if loss of myofiber mass as compared to loss of myofiber integrity and quality contributes more to the loss of muscle force [15, 57]. Rates of muscle atrophy and changes in muscle architecture have been quantified and are associated with poor clinical outcomes, although the role of assessment of skeletal muscle mass using computed tomography imaging and ultrasonography and assessment of fat-free mass using bioelectrical impedance analysis remain to be established [58, 59]. Nevertheless ICU-AW is associated with a longer hospital stay, decreased likelihood to go home after hospital discharge, and reduced long-term survival [60].

While it is evident that rehabilitation should play an important role, from other areas of research (sports, elderly), it is likely that the combination of protein and exercise will improve physical performance (Fig. 2) [61, 62]. Surprisingly, withholding PN in patients who received protocolized physiotherapy and passive or active bedcycling reduced the incidence of ICU-AW and enhanced recovery in a 600-patient substudy of the EPaNIC trial [15]. This underscores the fact that general principles that apply in other physiologic conditions may not apply to very early ICU nutrition.

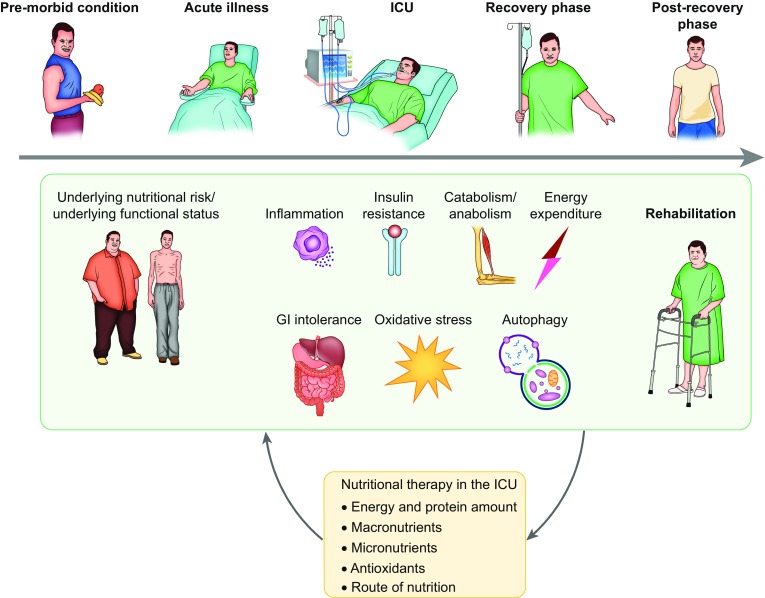

Fig. 2.

How does nutritional support during critical illness affect patient recovery? The effect of nutritional support on recovery may be influenced by the amount of calories, protein, other macronutrients, micronutrients, and route of administration. It is probably influenced by premorbid nutritional and functional status, by several pathophysiologic processes associated with critical illness, and by the level of rehabilitation. In return, all these variables may influence nutritional needs

While the benefit of early enhanced feeding has long been overestimated, the importance of prolonged often unnoticed and unintentional underfeeding is under addressed, particularly after ICU discharge to the conventional ward [63]. This deserves much more attention, as patients in this phase of recovery may be more likely to experience benefit by enhanced nutrition possibly in combination with physical exercise.

Management of intestinal and gastric feeding intolerance

A meta-analysis of 15 RCTs showed that small intestinal feeding compared to gastric feeding improved nutritional intake and reduced the incidence of ICU-acquired pneumonia but did not affect other clinically important outcomes [64]. However, the indications for small intestinal feeding (when? for whom?) in the ICU remain unclear.

Development of novel motility agents beyond erythromycin and metoclopramide remains an area of active investigation. Use of currently available agents is limited by the fear of adverse effects and tachyphylaxis as their efficacy decreases over time (4–5 days). A novel motilin agonist without antibiotic or cardiac effects has recently been shown to accelerate gastric emptying in critically ill patients (Supplementary References). However, the clinical benefits of gastric emptying acceleration and delivery of more nutrition still need to be proven and compared to post-pyloric feeding tubes.

Top ten studies/trials to be done in the next 10 years

Clinical trial design considerations

Outcomes

It is important that patient-centered outcomes be emphasized in clinical phase III trials evaluating nutritional interventions; these include mortality, complications (including infections), and functional outcomes (including the ability to perform prior activities and to return to work, muscle strength, walking distance, quality of life). Surrogate outcomes such as amount of calories/protein delivered, biochemical markers, and glycemic control should not be used as primary outcomes for these large-scale clinical trials.

Study size

Phase III RCTs must be adequately powered and power calculations must be performed using realistic event rates and expected effect size [65]. The ethics of conducting a study doomed to fail need to be questioned.

Time course of the disease and type of critical illness

It may be important to distinguish between acute critical illness, subacute critical illness, chronic critical illness, and the relatively stable postoperative ICU patient (Fig. 2). These different phases of critical illness, or specifically the points of “anabolic switch”, are as yet undefined. It is possible that, when relevant, nutritional support should be individualized on the basis of the patient evolution: as the patient improves clinically and can start rehabilitation, nutrition support should be adapted to the new health state.

Patients

It is of importance to focus on severe critical illness with patients who experience organ failure (requiring at least invasive mechanical ventilation) and whose outcome depends on nutritional support. The nutritional status of the patients included in the studies should be detailed according to prespecified variables and studies should include a priori stratification by nutritional risk. Specific types of patients should be identified (e.g., those with previous poor nutrition, postoperative, those without organ failure and sepsis).

Study design

Interpretation of many critical care nutritional observational studies is complicated by the presence of many confounders and competing outcomes. Adequately powered RCTs are the best approach to balance measured and unmeasured confounders. Many previous nutrition trials have been open to bias because they have been unblinded.

Top ten trials

There is considerable research being conducted in different aspects of nutrition therapy in critically ill patients. Table 3 summarizes open RCTs registered on clinicaltrials.gov as examples of ongoing work. The panel identified the following studies as the top 10 trials/studies for the next 10 years using the methodology outlined in the online supplement (Table 4). In brief, the panel members suggested candidate topics, then rated each one using a grading system (0–4). Potential studies were ranked on the basis of average score. The following received the highest priory scores.

To study the effects of high compared to low protein dose combined with standardized active and passive mobilization during the acute phase of critical illness on mortality and recovery of severely ill patients.

To study the effects of high compared to low protein dose combined with standardized active and passive mobilization during the post-acute phase of critical illness on mortality and recovery of severely ill patients.

To determine which patient groups benefit from specific nutritional interventions and which do not or experience harm. Such determination requires development and/or validation of clinical and laboratory nutritional assessment tools, with validation being best done in RCTs.

To examine the effects of permissive underfeeding (caloric restriction) with and without high-dose protein supplementation in critically ill obese on mortality and physical function.

To study the effects of continuous versus intermittent EN on mechanistic markers in a phase II trial to inform a phase III RCT with mortality and physical function being the main outcomes.

To study the effects of high compared to low energy dose with standardized active and passive mobilization post-acute phase of critical illness on mortality and recovery of severely ill patients.

To determine which bedside assessment of muscle mass can accurately identify low muscle mass, be used to monitor nutrition success, and predict functional recovery.

To perform a pragmatic RCT of standardized parenteral supplementation of daily requirements of all micronutrients until full EN is achieved in critically ill patients on mortality and/or functional recovery.

To evaluate the effects of prokinetic use on the recovery of critically ill patients with persistent intolerance to EN.

To study the effects of high vs low energy dose with standardized active and passive mobilization during the acute phase of critical illness on mortality and recovery of severely ill patients.

Table 3.

Randomized controlled trials registered on clinicaltrials.gov of nutrition studies in critically ill adults

| NCT number | Title | Recruitment | Interventions | Sponsor/collaborators | Enrollment | Start date | Completion date | Acronym |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of energy expenditure and monitoring of nutritional effects in different phases of critical illness and across patients with different nutritional risks | ||||||||

| NCT02897713 | Feasibility, safety, and outcomes of intensive enteral nutrition in patients with mechanical ventilation | Recruiting | Intensive enteral nutrition, routine enteral nutrition | Shanghai Zhongshan Hospital Shanghai 6th People’s Hospital Shanghai Tongji Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine Shanghai 10th People’s Hospital Shanghai Jinshan Hospital Shanghai Minhang Central Hospital Renji Hospital Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Xinhua Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine Shanghai East Hospital Xuhui Central Hospital, Shanghai Tongren Hospital, Shanghai |

400 | Nov-16 | Mar-18 | – |

| NCT02022813 | Impact of supplemental parenteral nutrition in ICU patients on metabolic, inflammatory, and immune responses | Recruiting | Supplemental parenteral nutrition (SPN) | Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois University of Geneva, Switzerland |

30 | Apr-14 | Dec-16 | SPN2 |

| NCT02306746 | The augmented versus routine approach to giving energy trial | Recruiting | TARGET protocol EN 1.5 kcal/ml, TARGET protocol EN 1.0 kcal/ml |

Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Research Centre | 4000 | Jun-16 | Apr-18 | TARGET |

| Timing and administration of enteral and parenteral nutrition | ||||||||

| NCT02358512 | Intermittent versus continuous feeding in ICU patients | Recruiting | Enteral feeding | Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust University College, London The Whittington Hospital NHS Trust |

116 | Feb-15 | Dec-17 | – |

| NCT02159456 | Continuous versus intermittent enteral feeding in critically ill patients | Recruiting | Continuous enteral feeding via infusion pump, intermittent enteral feeding via gravity-based infusion | Seoul National University Hospital | 70 | May-14 | Apr-17 | – |

| NCT02853799 | Comparison of the effects of intermittent and continuous enteral feeding on glucose-insulin dynamics in critically ill medical patients | Not yet recruiting | Osmolite 1.2 cal/ml enteral feeds | San Antonio Military Medical Center | 20 | Aug-16 | Oct-17 | – |

| Substrate requirements: proteins and carbohydrates | ||||||||

| NCT01934595 | Optimal protein supplementation for critically ill patients | Recruiting | Beneprotein | University of Oklahoma | 100 | Sep-13 | Sep-16 | – |

| NCT02755155 | Optimization of therapeutic human serum albumin infusion in selected critically ill patients | Not yet recruiting | Human serum albumin infusion 4%, human serum albumin infusion 20% | University Hospital, Strasbourg, France | 550 | Sep-16 | May-19 | AlbAlsace |

| NCT02503527 | Efficacy and safety study of a low-carbohydrate tube feed in critically ill patients under insulin therapy | Recruiting | Diben 1.5 kcal HP, Fresubin HP Energy Fibre (1.5 kcal) | Fresenius Kabi OE Clinical Trial Center (KKS) Universität Innsbruck International Medical Research-Partner GmbH dsh statistical services GmbH |

40 | Sep-15 | Sep-17 | – |

| NCT02106624 | A trial to assess the effect of high nitrogen intake in critically ill patients | Recruiting | Nitrogen supply | Shanghai Zhongshan Hospital | 80 | Mar-15 | Aug-17 | – |

| NCT02678325 | The basal enteral high protein study | Recruiting | Standardized high protein enteral nutrition, standardized normal protein enteral nutrition | University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland | 90 | May-16 | Oct-16 | – |

| NCT02584907 | Fat based enteral nutrition for blood glucose control in ICU | Recruiting | High fat enteral nutrition | Shahid Beheshti University | 88 | Oct-15 | Jan-17 | – |

| NCT02763553 | Does a ketogenic diet cause ketosis in patients on intensive care? | Not yet recruiting | Ketogenic feed, standard feed | University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust | 10 | Dec-16 | Mar-17 | – |

| NCT01833624 | Efficiency of a small-peptide enteral feeding formula compared to a whole-protein formula | Recruiting | Peptamen® AF, Sondalis® HP | Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Besancon Nestlé© Foundation |

206 | Jun-12 | Aug-17 | NUTRI_REA |

| NCT02865408 | Amino acid nutrition in the critically ill | Not yet recruiting | Peptamen 1.5% via enteral, Prosol 20% IV to 1.75 g/kg/day, Prosol 20% IV to 2.5 g/kg/day | McGill University Health Center | 30 | Sep-16 | Sep-19 | AA-ICU |

| Nutrition and functional recovery | ||||||||

| NCT02509520 | Assessing the effects of exercise, protein, and electric stimulation on intensive care unit patients outcomes | Recruiting | MPR and high protein supplement (HPRO), MPR and neuromusc electric stimulation (NMES)|, MPR and NMES and HPRO | University of Maryland | 60 | May-15 | Jul-17 | ExPrEs |

| NCT02773771 | Strategies to reduce organic muscle atrophy in the intensive care unit | Not yet recruiting | Beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate, Placebo, Vital HP® | Massachusetts General Hospital | 60 | Jan-17 | Jan-19 | STROMA-ICU |

| NCT02822170 | Nutrition and exercise in critical illness: a randomized trial of combined cycle ergometry and amino acids in the ICU | Not yet recruiting | Amino acid supplementation plus early in-bed cycle ergometry exercise | Clinical Evaluation Research Unit at Kingston General Hospital | 142 | May 2017 | May 2021 | NEXIS Trial |

| Management of intestinal and gastric feeding intolerance | ||||||||

| NCT02528760 | To determine the role of prokinetics in feed intolerance in critically ill cirrhosis | Recruiting | Metaclopramide, erythromycin, placebo | Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, India | 162 | Sep-15 | Feb-17 | – |

| NCT01934192 | Nutritional adequacy therapeutic enhancement in the critically ill: a randomized double blind, placebo-controlled trial of the motilin receptor agonist GSK962040 | Finished recruiting | Novel motilin agonist vs. placebo | Clinical evaluation research unit at Kingston General Hospital | 150 | August 2013 | July 2016 | The NUTRIATE study |

| NCT02459275 | PEP uP protocol in surgical patients | Recruiting | PEP uP protocol | Clinical Evaluation Research Unit at Kingston General Hospital | 100 | Jul-15 | Sep-17 | – |

| NCT02609620 | Safety & initial efficacy of the LunGuard PFT Sys. on Enteral-Fed, sedated and mechanically ventilated patients peristaltic feeding tube | Not yet recruiting | Peristaltic feeding tube, ConvaTec levin duodenal tube | LunGuard Ltd. | 20 | Dec-15 | Oct-16 | PFT |

| NCT02705027 | Comparison of two endoscopically placed nasojejunal probes | Recruiting | Freka®-Trilumina versus Freka®-EasyIn | Ruhr University of Bochum | 64 | Aug-12 | Aug-16 | – |

| NCT02515123 | Promotion of esophageal motility to prevent regurgitation and enhance nutrition intake in ICU patients | Recruiting | E-motion system, sham E-motion system | E-Motion Medical Ltd. Clinical Evaluation Research Unit at Kingston General Hospital |

140 | Feb-16 | Dec-17 | PROPEL |

| Immune-modulating nutrition | ||||||||

| NCT02738762 | Glutamine supplementation | Not yet recruiting | Glutamine supplementation | Medical Centre Leeuwarden | 80 | Jun-16 | Mar-17 | – |

| NCT01162928 | Parenteral nutrition with intravenous and oral fish oil for intensive care patients | Recruiting | Nutriflex Omega special + Oxepa, Nutriflex Lipid special + Pulmocare | B. Braun Melsungen AG | 100 | May-13 | Jan-18 | – |

| NCT02189538 | Effect of n-3 PUFA from fish in enteral nutrition of major burn patients | Recruiting | ω-3 PUFA, low fat enteral diet | Centro Nacional de Quemados, Uruguay | 100 | Jan-13 | Feb-17 | OmegaBurn |

| NCT02868827 | Cholecalciferol supplementation in critically ill patients with severe vitamin D deficiency | Not yet recruiting | Cholecalciferol, milk (Nestle) | King Abdullah Medical City | 430 | Oct-16 | Dec-18 | – |

| NCT01704430 | Glutamine to improve outcomes in cardiac surgery | Recruiting | Glutamine, maltodextrin | University of Alberta | 100 | Sep-12 | Jul-16 | GLADIATOR |

| NCT02594579 | Effect of vitamin D3 supplementation on muscle mass in ICU patient | Not yet recruiting | Vitamin D3, placebo | Mahidol University | 40 | Oct-15 | Dec-16 | – |

| NCT00985205 | A randomized trial of ENtERal glutamine to minimize thermal injury | Recruiting | Enteral glutamine vs. placebo | Clinical Evaluation Research Unit at Kingston General Hospital | 2700 | Jul-15 | July 2021 | The RE_ENERGIZE trial |

| NCT02002247 | SodiUm SeleniTe administration IN cardiac surgery: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial of high-dose sodium-selenite administration in high-risk cardiac surgical patients |

Recruiting | High-dose intravenous Selenium vs. placebo | Clinical Evaluation Research Unit at Kingston General Hospital | 1400 | Oct-15 | October 2019 | SUSTAIN CSX®-trial |

| NCT02864017 | Immuno nutrition by l-citrulline for critically ill patients | Recruiting | Enteral nutrition, l-citrulline, placebo | Rennes University Hospital | 120 | Sep-16 | Oct-18 | Immunocitre |

| Others | ||||||||

| NCT01477320 | Enteral nutrition as stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients | Recruiting | Pantoprazole 40 mg IV daily and tube feed, placebo and tube feed | Abbott nutrition University of Louisville |

198 | Aug-13 | Oct-17 | – |

We searched for “open” “interventional” studies in “adults” and “seniors” on November 28, 2016 using the following search strategy: “nutrition” OR “feeding” OR “enteral feeding” OR “feed” OR “energy” OR “formula” OR “protein” OR “parenteral nutrition” | open studies | interventional studies | “critical illness” OR “mechanical ventilation” OR “inflammation” OR “intensive care” OR “intensive care unit” OR “critically ill” | adult, senior. The search revealed 58 studies. The results were evaluated manually and studies of other scopes (non-randomized, non-nutrition) were removed from the list

Table 4.

Selecting the top 10 trials in critical care nutrition and metabolism

| Topic # | Candidate research topic | Average score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Effects of high vs low protein dose combined with standardized active and passive mobilization during the acute phase of critical illness on (mortality and) recovery (physical function, ICU length of stay) of severely ill patients (treated with mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drugs during the acute phase). The study should include a priori stratification by nutritional risk | 3.71 |

| 2 | Effects of high vs low protein dose combined with standardized active and passive mobilization post-acute phase of critical illness on (mortality and) recovery (physical function, ICU length of stay, MV duration) of severely ill patients (treated with mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drug during the acute phase). The study should include a priori stratification by nutritional risk | 2.93 |

| 3 | Comparative study of different nutritional assessment tools to identify the best tool that differentiates the response to caloric and protein intake | 2.93 |

| 4 | Effects of permissive underfeeding (calories) with and without high-dose protein supplementation in critically ill obese on (mortality and) physical function | 2.57 |

| 5 | Effects of continuous versus intermittent (infuse 20–30 min, off 90 min, repeat q 2 h) feeding on mechanistic markers as a prerequisite to a larger RCT | 2.36 |

| 6 | Best feeding strategy for sepsis patients with respect to calories and proteins | 2.36 |

| 7 | Effects of high vs low energy dose with standardized active and passive mobilization post-acute phase of critical illness on (mortality and) recovery (physical function, ICU length of stay) of severely ill patients (treated with mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drug during the acute phase) | 2.29 |

| 8 | Effects of continuous versus intermittent (infuse 20–30 min, off 90 min, repeat q 2 h) feeding on (mortality and) physical function | 2.21 |

| 9 | What bedside assessment of muscle mass can accurately identify low muscle mass, be used to monitor nutrition success, and predict for function recovery? | 2.14 |

| 10 | A pragmatic RCT of standardized parenteral supplementation of daily requirements of all micronutrients until full EN is achieved in critically ill patients on mortality and/or functional recovery | 2.14 |

| 11 | RCT evaluating the effects of prokinetic use on the recovery of critically ill patients with persistent intolerance to EN | 2.00 |

| 12 | Effects of high vs low energy dose with standardized active and passive mobilization during the acute phase of critical illness on (mortality and) recovery (physical function, ICU length of stay) of severely ill patients (treated with mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drug during the acute phase) | 1.93 |

| 13 | Effects of stepwise increases in caloric provision during the first week on the complication rate and physical function | 1.93 |

| 14 | Whey-based protein (high in leucine) (with or without some form of exercise) compared to soy or casein-based protein on mortality and physical function | 1.86 |

| 15 | Revisiting liberal versus strict glucose control in a setting of tolerated early hypocaloric feeding, strict separation of the glucose levels obtained in the liberal and strict arm in non-diabetic and diabetic critically ill patients on mortality, organ function, and functional status | 1.79 |

| 16 | Effects of permissive underfeeding (calories) with high-dose protein supplementation in critically ill diabetic patients on (mortality and) physical function | 1.71 |

| 17 | Nutrition and physical activity guided by muscle mass assessment on (mortality and) long-term physical function | 1.50 |

| 18 | RCT of small peptide vs polymeric in patients at high risk of intolerance on (mortality and) recovery (physical function, ICU length of stay) and nutritional adequacy (intake) | 1.36 |

| 19 | Use of resolvins and/or protectins in critically ill patients. The main outcomes are mortality and physical function | 1.29 |

| 20 | The effect of GLP-1 and its agonists in hyperglycemic critically ill patients on mortality on mortality, organ function, and functional status | 1.14 |

| 21 | The effect of insulin glargine in hyperglycemic critically ill patients on mortality, organ function, and functional status | 1.07 |

Members of the panel suggested candidate topics that underwent several rounds of discussion. Finally, the panel reached a list of 21 topics. Members of the panel rated each one of the topics using a grading system: 4 top priority, 3 high priority, 2 intermediate priority, 1 low priority, and 0 not a priority. For each candidate topic we calculate the average score given by the panel. The table shows the 21 topics with the average score in descending order. After finalizing the survey, the panel reviewed the top 10 topics. The panel agreed on merging topics 5 and 8 and on deleting item 6 as it was covered by earlier items. As such items 11 and 12 were moved up in rank

In conclusion, recent trials have answered important questions but also highlighted or revealed several uncertainties in many aspects of critical care nutrition and metabolism. We ranked the top 10 studies for the next 10 years, with the prospect that different nutritional interventions targeted to the appropriate patient population will be examined for their effect on facilitating recovery and improving survival in adequately powered and properly designed studies, probably in conjunction with mobilization. Undoubtedly, the next 10 years are likely to be an exciting era for nutrition and metabolism.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00134-017-4711-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Preiser JC, van Zanten AR, Berger MM, et al. Metabolic and nutritional support of critically ill patients: consensus and controversies. Crit Care. 2015;19:35. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0737-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhaliwal R, Madden SM, Cahill N, et al. Guidelines, guidelines, guidelines: what are we to do with all of these North American guidelines? JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2010;34:625–643. doi: 10.1177/0148607110378104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraipont V, Preiser JC. Energy estimation and measurement in critically ill patients. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2013;37:705–713. doi: 10.1177/0148607113505868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oshima T, Berger MM, De Waele E et al (2016) Indirect calorimetry in nutritional therapy. A position paper by the ICALIC study group. Clin Nutr. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Taylor BE, McClave SA, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) Crit Care Med. 2016;44(2):390–438. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice TW, Mogan S, Hays MA, Bernard GR, Jensen GL, Wheeler AP. Randomized trial of initial trophic versus full-energy enteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients with acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:967–974. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a905a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Sydrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network. Rice TW, et al. Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:795–803. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arabi YM, Aldawood AS, Haddad SH, et al. Permissive underfeeding or standard enteral feeding in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2398–2408. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Dorzi HM, Albarrak A, Ferwana M, Murad MH, Arabi YM. Lower versus higher dose of enteral caloric intake in adult critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2016;20:358. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1539-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marik PE, Hooper MH. Normocaloric versus hypocaloric feeding on the outcomes of ICU patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:316–323. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-4131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casaer MP, Mesotten D, Hermans G, et al. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:506–517. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fivez T, Kerklaan D, Mesotten D, et al. Early versus late parenteral nutrition in critically ill children. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1111–1122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doig GS, Simpson F, Sweetman EA, et al. Early parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients with short-term relative contraindications to early enteral nutrition: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:2130–2138. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heidegger CP, Berger MM, Graf S, et al. Optimisation of energy provision with supplemental parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2013;381:385–393. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61351-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermans G, Casaer MP, Clerckx B, et al. Effect of tolerating macronutrient deficit on the development of intensive-care unit acquired weakness: a subanalysis of the EPaNIC trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1:621–629. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey SE, Parrott F, Harrison DA, et al. Trial of the route of early nutritional support in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1673–1684. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elke G, van Zanten AR, Lemieux M, et al. Enteral versus parenteral nutrition in critically ill patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2016;20:117. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1298-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Jiang X, Day AG. Identifying critically ill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: the development and initial validation of a novel risk assessment tool. Crit Care. 2011;15:R268. doi: 10.1186/cc10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman A, Hasan RM, Agarwala R, Martin C, Day AG, Heyland DK. Identifying critically-ill patients who will benefit most from nutritional therapy: further validation of the “modified NUTRIC” nutritional risk assessment tool. Clin Nutr. 2015;35:158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arabi YM, Aldawood AS, Al-Dorzi HM, et al (2017) Permissive underfeeding or standard enteral feeding in high and low nutritional risk critically ill adults: post-hoc analysis of the permit trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195:652–662 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hiesmayr M, Frantal S, Schindler K, et al. The Patient- And Nutrition-Derived Outcome Risk Assessment Score (PANDORA): development of a simple predictive risk score for 30-day in-hospital mortality based on demographics, clinical observation, and nutrition. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg O, Stanga Z, Ad Hoc ESPEN Working Group Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:321–336. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5614(02)00214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doig GS, Simpson F, Heighes PT, et al. Restricted versus continued standard caloric intake during the management of refeeding syndrome in critically ill adults: a randomised, parallel-group, multicentre, single-blind controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:943–952. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00418-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casaer MP, Wilmer A, Hermans G, Wouters PJ, Mesotten D, Van den Berghe G. Role of disease and macronutrient dose in the randomized controlled EPaNIC trial: a post hoc analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:247–255. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-0999OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reignier J, Mercier E, Le Gouge A, et al. Effect of not monitoring residual gastric volume on risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults receiving mechanical ventilation and early enteral feeding: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:249–256. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.196377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montejo JC, Minambres E, Bordeje L, et al. Gastric residual volume during enteral nutrition in ICU patients: the REGANE study. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:1386–1393. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1856-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapman MJ, Besanko LK, Burgstad CM, et al. Gastric emptying of a liquid nutrient meal in the critically ill: relationship between scintigraphic and carbon breath test measurement. Gut. 2011;60:1336–1343. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.227934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kieft H, Roos AN, van Drunen JD, Bindels AJ, Bindels JG, Hofman Z. Clinical outcome of immunonutrition in a heterogeneous intensive care population. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:524–532. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2564-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heyland D, Muscedere J, Wischmeyer PE, et al. A randomized trial of glutamine and antioxidants in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1489–1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, et al. Enteral omega-3 fatty acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidant supplementation in acute lung injury. JAMA. 2011;306:1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Zanten AR, Sztark F, Kaisers UX, et al. High-protein enteral nutrition enriched with immune-modulating nutrients vs standard high-protein enteral nutrition and nosocomial infections in the ICU: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:514–524. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Zanten AR, Dhaliwal R, Garrel D, Heyland DK. Enteral glutamine supplementation in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2015;19:294. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1002-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luiking YC, Poeze M, Deutz NE. Arginine infusion in patients with septic shock increases nitric oxide production without haemodynamic instability. Clin Sci (Lond) 2015;128:57–67. doi: 10.1042/CS20140343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359–1367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van den Berghe G, Wilmer A, Hermans G, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the medical ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:449–461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marik PE, Preiser JC. Toward understanding tight glycemic control in the ICU: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;137:544–551. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.NICE-SUGAR Study Investigators. Finfer S, Chittock DR, et al. Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1283–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van den Berghe G. Intensive insulin therapy in the ICU–reconciling the evidence. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:374–378. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haugen HA, Chan LN, Li F. Indirect calorimetry: a practical guide for clinicians. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22:377–388. doi: 10.1177/0115426507022004377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singer P, Berger MM, Van den Berghe G, et al. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: intensive care. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casaer MP, Ziegler TR. Nutritional support in critical illness and recovery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:734–745. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marik PE. Feeding critically ill patients the right ‘whey’: thinking outside of the box. A personal view. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:51. doi: 10.1186/s13613-015-0051-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.West DW, Burd NA, Coffey VG, et al. Rapid aminoacidemia enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis and anabolic intramuscular signaling responses after resistance exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:795–803. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.013722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gazzaneo MC, Suryawan A, Orellana RA, et al. Intermittent bolus feeding has a greater stimulatory effect on protein synthesis in skeletal muscle than continuous feeding in neonatal pigs. J Nutr. 2011;141:2152–2158. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.147520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liebau F, Sundstrom M, van Loon LJ, Wernerman J, Rooyackers O. Short-term amino acid infusion improves protein balance in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2015;19:106. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0844-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chowdhury AH, Murray K, Hoad CL, et al. Effects of bolus and continuous nasogastric feeding on gastric emptying, small bowel water content, superior mesenteric artery blood flow, and plasma hormone concentrations in healthy adults: a randomized crossover study. Ann Surg. 2016;263:450–457. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doig GS, Simpson F, Bellomo R, et al. Intravenous amino acid therapy for kidney function in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1197–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrie S, Allman-Farinelli M, Daley M, Smith K. Protein requirements in the critically ill: a randomized controlled trial using parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2015;40:795–805. doi: 10.1177/0148607115618449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casaer MP, Van den Berghe G. Comment on “Protein requirements in the critically ill: a randomized controlled trial using parenteral nutrition”. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016;40:763. doi: 10.1177/0148607116638494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rugeles S, Villarraga-Angulo LG, Ariza-Gutierrez A, Chaverra-Kornerup S, Lasalvia P, Rosselli D. High-protein hypocaloric vs normocaloric enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. J Crit Care. 2016;35:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nicolo M, Heyland DK, Chittams J, Sammarco T, Compher C. Clinical outcomes related to protein delivery in a critically ill population: a multicenter, multinational observation study. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016;40:45–51. doi: 10.1177/0148607115583675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weijs PJ, Looijaard WG, Beishuizen A, Girbes AR, Oudemans-van Straaten HM. Early high protein intake is associated with low mortality and energy overfeeding with high mortality in non-septic mechanically ventilated critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2014;18:701. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0701-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rugeles SJ, Rueda JD, Diaz CE, Rosselli D. Hyperproteic hypocaloric enteral nutrition in the critically ill patient: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17:343–349. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.123438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verreijen AM, Verlaan S, Engberink MF, Swinkels S, de Vogel-van den Bosch J, Weijs PJ. A high whey protein-, leucine-, and vitamin D-enriched supplement preserves muscle mass during intentional weight loss in obese older adults: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:279–286. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.090290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stroud M. Protein and the critically ill; do we know what to give? Proc Nutr Soc. 2007;66:378–383. doi: 10.1017/S0029665107005642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wollersheim T, Woehlecke J, Krebs M, et al. Dynamics of myosin degradation in intensive care unit-acquired weakness during severe critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:528–538. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3224-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paris M, Mourtzakis M. Assessment of skeletal muscle mass in critically ill patients: considerations for the utility of computed tomography imaging and ultrasonography. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2016;19:125–130. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thibault R, Makhlouf AM, Mulliez A, et al. Fat-free mass at admission predicts 28-day mortality in intensive care unit patients: the international prospective observational study Phase Angle Project. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1445–1453. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hermans G, Van Mechelen H, Clerckx B, et al. Acute outcomes and 1-year mortality of intensive care unit-acquired weakness. A cohort study and propensity-matched analysis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:410–420. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201312-2257OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim HK, Suzuki T, Saito K, et al. Effects of exercise and amino acid supplementation on body composition and physical function in community-dwelling elderly Japanese sarcopenic women: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heyland DK, Stapleton RD, Mourtzakis M, et al. Combining nutrition and exercise to optimize survival and recovery from critical illness: conceptual and methodological issues. Clin Nutr. 2016;35:1196–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hiesmayr M, Schindler K, Pernicka E, et al. Decreased food intake is a risk factor for mortality in hospitalised patients: the NutritionDay survey 2006. Clin Nutr. 2009;28:484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deane AM, Dhaliwal R, Day AG, Ridley EJ, Davies AR, Heyland DK. Comparisons between intragastric and small intestinal delivery of enteral nutrition in the critically ill: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2013;17:R125. doi: 10.1186/cc12800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Summers MJ, Chapple LA, McClave SA, Deane AM. Event-rate and delta inflation when evaluating mortality as a primary outcome from randomized controlled trials of nutritional interventions during critical illness: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:1083–1090. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.