Abstract

Antimicrobial proteins and peptides (AMPs) are a central component of the antibacterial activity of airway epithelial cells. It has been proposed that a decrease in antibacterial lung defense contributes to an increased susceptibility to microbial infection in smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, whether reduced AMP expression in the epithelium contributes to this lower defense is largely unknown. We investigated the bacterial killing activity and expression of AMPs by air-liquid interface-cultured primary bronchial epithelial cells from COPD patients and non-COPD (ex-)smokers that were stimulated with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi). In addition, the effect of cigarette smoke on AMP expression and the activation of signaling pathways was determined. COPD cell cultures displayed reduced antibacterial activity, whereas smoke exposure suppressed the NTHi-induced expression of AMPs and further increased IL-8 expression in COPD and non-COPD cultures. Moreover, smoke exposure impaired NTHi-induced activation of NF-κB, but not MAP-kinase signaling. Our findings demonstrate that the antibacterial activity of cultured airway epithelial cells induced by acute bacterial exposure was reduced in COPD and suppressed by cigarette smoke, whereas inflammatory responses persisted. These findings help to explain the imbalance between protective antibacterial and destructive inflammatory innate immune responses in COPD.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptides, Epithelium, Host defense, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Cigarette smoke

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a severe inflammatory lung disorder in which colonization and infections with opportunistic respiratory bacteria are a major disease hallmark [1]. It is hypothesized that a vicious circle of attenuated antibacterial lung defense, enhanced bacterial colonization, and the induction of lung inflammation and injury contribute to the disease [2]. However, the underlying mechanisms remain incompletely understood.

Smoking is the main risk factor for COPD development, and is furthermore associated with an increased susceptibility to respiratory infections [3]. Despite the strong association, only a subpopulation of approximately 15–20% of smokers develop the disease. This suggests that there are differences between susceptible smokers and smokers with a normal lung function that may help to explain disease etiology. These differences may persist in cell culture [4, 5]; for this reason, comparison of cell cultures from COPD patients and non-COPD smokers may reveal differences in host defense activities that may help to explain the increased microbial susceptibility.

Airway epithelial cells contribute to innate lung defense by displaying direct antibacterial activity, which is mediated in part by the production of antimicrobial proteins and peptides (AMPs) [6, 7]. In addition to AMPs that are expressed on a steady-state basis, others are induced for example upon the recognition of microbes or microbial structures by pattern recognition receptors. This response is highly similar amongst species, and murine models have shown that the inducible antibacterial activity of airway epithelial cells provides full protection against various pathogenic microbes without further involvement of immune cells [8]. Impairment of this induced activity in COPD might therefore contribute to the increased susceptibility to infection with respiratory pathogens.

Observational studies in lung tissue, airway secretions, and tracheal washings have shown that the expression of several AMPs is reduced in smokers and patients with COPD, including the microbial-induced antimicrobial peptide human β-defensin-2 (hBD-2) [9, 10, 11, 12]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that cigarette smoke (CS) exposure attenuated the antibacterial activity and microbial-induced expression of hBD-2 in cultured airway epithelial cells [12, 13, 14]. This suggests that the inducible antibacterial activity is affected in airway epithelial cells from smokers and COPD patients. However, it is unclear whether this activity differs between airway epithelial cells from non-COPD smokers and COPD patients. Interestingly, microbial-induced expression of the proinflammatory mediator IL-8 is not reduced by CS [14, 15]. Conflicting to this, cellular signal transduction pathways regulating the expression of AMPs and proinflammatory mediators largely overlap [16, 17], and it is unknown whether imbalances in these signaling pathways reflect the alterations in AMP and proinflammatory mediator expression.

To gain greater insight into the role of the inducible antibacterial defense function of airway epithelial cells in COPD, we examined the antibacterial activity and expression of AMPs following acute bacterial exposure of cultured airway epithelial cells from mild-to-moderate COPD patients and (ex-)smokers with a normal lung function (non-COPD). To understand the mechanism underling reduced AMP expression, we determined the effect of CS on the microbial-induced expression of AMPs, and the regulation of cellular signal transduction pathways.

Materials and Methods

Primary Bronchial Epithelial Cell Cultures and Stimuli

Primary bronchial epithelial cells (PBEC) were isolated from tumor-free resected lung tissue and cultured in an air-liquid interface model (further referred to as ALI-PBEC) to obtain mucociliary-differentiated cultures, essentially as previously described [14, 18]. PBEC cultures were used from a total of 28 patients, all undergoing lung resection surgery for lung cancer. Clinical histories and lung function data were obtained from anonymized patients. Disease status was determined based on lung function according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease classification [19]. The patients included 15 COPD and 13 non-COPD subjects (see Tables 1 and 2 for indicated experiments). Both groups included current smokers and ex-smokers. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) strain D1 [20] was cultured and ultraviolet (UV) inactivated as described earlier [14]. UV-inactivated NTHi was applied to the apical surface of ALI-PBEC in a volume of 100 µL; PBS was used for dilutions and as a negative control. ALI-PBEC were exposed to mainstream CS from 3R4F reference cigarettes (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA) using a previously described exposure model [14, 15]. In brief, epithelial cultures were placed in room air (AIR; control) or CS exposure chambers, localized in a tissue incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. In these exposure chambers, ALI-PBEC were respectively exposed to AIR or CS from 1 cigarette (approximately 2 mg of CS particles), which was infused by a mechanical pump with a continuous flow of 1 L/min for a period of 4–5 min. Residual CS was removed by flushing the chamber with air derived from the incubator for 10 min. After exposure, cells were stimulated at the apical surface with UV-inactivated NTHi or PBS (negative control).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics for use of the bacterial killing assay

| COPD | Non-COPD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 5 | 5 | |

| Female/male | 2/3 | 2/3 | |

| Age, years | 66±11 | 64±7 | 0.6 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 68±17 | 96±14 | 0.05 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 58±7 | 78±4 | <0.01 |

Age and lung function data are shown as means ± SD. The mean differences in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC were compared using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics for NTHi-induced AMP expression

| COPD | Non-COPD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 8 | |

| Female/male | 3/9 | 2/6 | |

| Age, years | 68±8 | 66±8 | 0.56 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 64±21 | 85±15 | 0.04 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 55±10 | 80±9 | <0.0001 |

Age and lung function are shown as means ± SEM. The mean differences in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC were compared using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Bacterial Killing Assay

The bacterial killing assay was adapted from Pezzulo et al. [21]. Instead of golden grids, bacteria were linked to glass coverslips. Six-millimeter-round coverslips were rinsed in ethanol, dried at room temperature, and subsequently silanized with 2% (v/v) APTES ([3-aminopropyl]triethoxysilane, H2N(CH2)3Si(OC2H5)3; Sigma-Aldrich) solution in acetone for 10 s. After rinsing in H2O for 10 min and drying at room temperature, the coverslips were immersed in 1 mM of MUA (11-mercaptoundecanoic acid, HS(CH2)10COOH, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at room temperature. Afterwards, coverslips were incubated in 0.1 M of NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) and 0.1 M of EDC (1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide, 1:2 molar ratio; both from Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min, and subsequently coated for 30 min with 10 μg/mL of streptavidin (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS. Next, the coverslips were washed and immersed with 1 M of glycine for 30 min. 1 × 108 CFU/mL (OD600) of log phase growth cultured NTHi was incubated in 0.88 mg/mL of N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide-biotin (sulfo-NHS-biotin; Thermo Scientific) for 30 min on ice. Next, biotin-labeled NTHi was linked to the surface of the streptavidin-coated glass coverslips in PBS for 30 min and subsequently washed twice in PBS and finally in 0.01 M of phosphate buffer pH 7.4, to remove the unbound bacteria. The bacterial killing activity was determined of ALI-PBEC that were prestimulated with UV-inactivated NTHi or PBS (untreated control), which was applied at the apical surface. After 6 h of incubation, cultures were washed with PBS and incubated for 48 h. Afterwards, NTHi-coated coverslips were placed on the apical surface of ALI-PBEC for 1 min. The coverslips were subsequently stained for 30 s with SYTO 9 and propidium iodide (both Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany), to visualize the live and dead bacteria, respectively. The coverslips were mounted on microscopic slides and covered in Baclight mounting oil (Life Technologies). Digital images were made with a Zeiss Axio Scope A1 fluorescent microscope and Zeiss Axiocam mRc 5 camera (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Göttingen, Germany). The number of live and dead bacteria was analyzed using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). The bacterial killing activity was determined by calculating the percentage of dead bacteria.

Microarray Gene Expression Analysis

Primary bronchial epithelial cells from 6 different donors were cultured in submerged conditions as previously described [14]. Cells were left unstimulated or triggered with UV-killed NTHi. RNA from these cultures were then isolated at 2 timepoints, early (6 h) and late (24 h), and subsequently subject to whole genome profiling of gene expression by microarray (Affymetrix GeneTitan platform).

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

RNA was isolated from ALI-PBEC using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA quantities were determined using the Nanodrop ND-1000 UV-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription PCR of 1 μg of RNA, using oligo-dT primers (Qiagen) and Moloney murine leukemia virus polymerase (Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was conducted using IQ SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad) and a CFX-384 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). qPCR reactions were performed using the primers shown in Table 3. The housekeeping genes RPL13A and ATP5B were selected using the “Genorm method” (Genorm; Primer Design, Southampton, UK). Bio-Rad CFX manager 3.0 software (Bio-Rad) was used to calculate the arbitrary gene expression using the standard curve method.

Table 3.

qPCR primer sequences

| Gene | Forward primer (5′−3′) | Reverse primer (5′−3′) |

|---|---|---|

| DEFB4/hBD-2 | ATCAGCCATGAGGGTCTTG | GCAGCATTTTGTTCCAGG |

| CCL20 | GCAAGCAACTTTGACTGCTG | TGGGCTATGTCCAATTCCAT |

| LCN2 | CCTCAGACCTGATCCCAGC | CAGGACGGAGGTGACATTGTA |

| S100A7 | ACGTGATGACAAGATTGACAAGC | GCGAGGTAATTTGTGCCCTTT |

| TLR2 | TCTCGCAGTTCCAAACATTCCAC | TTTATCGTCTTCCTGCTTCAAGCC |

| ATF3 | CCTCTGCGCTGGAATCAGTC | TTCTTTCTCGTCGCCTCTTTTT |

| pri-mir-147b | TTCATGACTGTGGCGGCGGG | GGCGAGGGCTCGTCATTTGGT |

| A20 | TCCTCAGGCTTTGTATTTGAGC | TGTGTATCGGTGCATGGTTTTA |

| DEFB3/hBD-3 | AGCCTAGCAGCTATGAGGATC | CTTCGGCAGCATTTTGCGCCA |

| CAMP/LL-37 | TCATTGCCCAGGTCCTCAG | TCCCCATACACCGCTTCAC |

| SLPI | GAGATGTTGTCCTGACACTTGTG | AGGCTTCCTCCTTGTTGGGT |

| DEFB1/hBD-1 | ATGAGAACTTCCTACCTTCTGCT | TCTGTAACAGGTGCCTTGAATTT |

| IL8 | CAGCCTTCCTGATTTCTG | CACTTCTCCACAACCCTCTGC |

| IL6 | CAGAGCTGTGCAGATGAGTACA | GATGAGTTGTCATGTCCTGCAG |

| NFKBIA | TGTGCTTCGAGTGACTGACC | TCACCCCACATCACTGAACG |

| ZC3H12A | GTACGTCTCCCAGGATTGCC | GGGACTGTAGCCCGTGTAAG |

| NFKBIZ | AGAGGCCCCTTTCAAGGTGT | TCCATCAGACAACGAATCGGG |

| FOS | CCTAACCGCCACGATGATGT | TCTGCGGGTGAGTGGTAGTA |

| JUN | TCCTGCCCAGTGTTGTTTGT | GACTTCTCAGTGGGCTGTCC |

| FOSL1 | AACCGGAGGAAGGAACTGAC | CTGCAGCCCAGATTTCTCAT |

| RPL13A | AAGGTGGTGGTCGTACGCTGTG | CGGGAAGGGTTGGTGTTCATCC |

| ATP5B | TCACCCAGGCTGGTTCAGA | AGTGGCCAGGGTAGGCTGAT |

ELISA

Secretion of innate immune mediators by ALI-PBEC was determined in the apical surface liquid, collected by washing the apical surface with 100 µL of PBS for 15 min, and in the basal medium as indicated. The secretion of IL-8 (Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and CCL20 (R&D, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was determined by ELISA following the manufacturer's protocol. Reagent for hBD-2 detection was a generous gift from D. Proud (Calgary, AB, Canada), and the hBD-2 ELISA was conducted as previously described [22]. The optical density values were measured with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

Transepithelial Electrical Resistance

The epithelial barrier integrity of ALI-PBEC cultures was determined by measuring the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) using the MilliCell-ERS (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA).

Western Blot

ALI-PBEC were washed 3 times with cold PBS and cell lysis was performed in lysis buffer consisting of 150 mM of NaCl, 50 mM of Tris HCl pH 7.4, 0.1% NP-40 (v/v), and EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Samples were subsequently mixed with sample buffer, consisting of 0.5 M of Tris pH 6.8, 10% SDS (w/v), 20% glycerol (v/v), 0.02% bromophenol blue, and 50 mM of DTT. Nuclear fractions were isolated using the NE-PER Nuclear Protein Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis on 10% glycine-based gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) skimmed milk (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS/0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 and stained with primary antibodies in 5% (w/v) BSA PBS/0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 overnight at 4°C. Antibodies were used to detect p-IKKα/β, IKKβ, IκB-α, p- and t-ERK1/2, p- and t-p38, TBP (all Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA), p50, p65 (both Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and β-actin (Leica). Next, membranes were stained with secondary HRP-labeled antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) in 5% (w/v) skimmed milk (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS/0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 for 1 h. Afterwards, membranes were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific). The intensity of bands were quantified by densitometry using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Immunofluorescence Confocal Microscopy

ALI-PBEC were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, permeabilized in 100% methanol for 10 min at 4°C, and blocked in blocking solution consisting of 5% (w/v) BSA, 0.3% (v/v) Triton X in PBS. Between each step, cells were washed 3 times with PBS. Afterwards, the PBEC-containing filters were cut from the Transwell using a razorblade and subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-mouse p50 or anti-rabbit p65 primary antibodies (both Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted in blocking solution. Next, filters were washed 3 times in PBS and stained with goat anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 568 or goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor 488 (both Life Technologies), respectively, and DAPI as nuclear staining. Secondary antibodies and DAPI were diluted in blocking solution and incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. Afterwards, the filters were washed 3 times with PBS and mounted on coverslips with Vectashield Hard Set Mounting Medium (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA, USA). Images were made using a Leica TCS SP5 confocal inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems) and processed using the Leica Application Suite Advanced Fluorescence software (LAS AF; Leica Microsystems).

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad PRISM 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The analysis of differences was conducted with a 1- or 2-way repeated measurements ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test and (un)paired Student t test as indicated. Differences were considered significant with p < 0.05.

Results

Lower NTHi-Induced Antibacterial Activity by COPD Airway Epithelial Cells

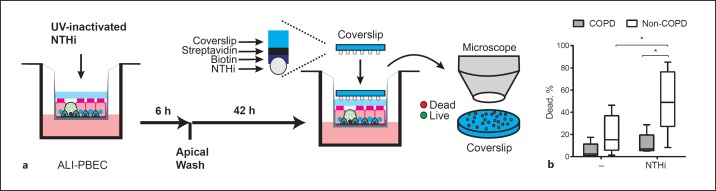

We first determined the bacterial killing activity of cultured ALI-PBEC from COPD patients and non-COPD (ex-)smokers. ALI-PBEC were first stimulated at the apical surface with UV-inactivated NTHi or PBS (negative control) to investigate microbial exposure-induced and baseline antibacterial activity. At 6 h after stimulation, the apical surface was washed and cells were incubated for an additional 42 h prior to assessment of the antibacterial activity (Fig. 1a). A killing assay was used that allows direct assessment of the antibacterial activity of the airway surface liquid of cultured ALI-PBEC by placing NTHi-coated coverslips on the apical surface. Minimal antibacterial activity was seen in control-treated ALI-PBEC from both COPD and non-COPD donors (Fig. 1b). Exposure to NTHi significantly increased the antibacterial activity of non-COPD cultures. In contrast, this increase was not observed in COPD epithelia. These findings suggest that cultured airway epithelial cells from COPD patients have reduced microbial-induced antibacterial activity compared to cell cultures from non-COPD (ex-)smokers.

Fig. 1.

Impaired bacterial killing by COPD ALI-PBEC. a Schematic representation of the bacterial killing assay. ALI-PBEC cultures were stimulated with 0.5 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi or PBS as the negative control for 6 h, washed at the apical surface, and incubated for 42 h. Next, streptavidin-coated glass coverslips linked to biotin-bound NTHi were placed on the apical surface of ALI-PBEC. Bacterial killing was determined by counting individual live and dead bacteria. b Bacterial killing was assessed for cultured ALI-PBEC from COPD patients (gray boxplots, n = 5 patients) and non-COPD smokers (white boxplots, n = 5 patients), either unstimulated or stimulated with 0.5 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi. Data are shown as the percentage of dead bacteria. The killing assay was performed in triplicates. COPD and non-COPD comparison results are depicted as boxplots with whiskers from minimum to maximum or bars (means ± SEM). The analysis of differences was conducted with a 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test. * p < 0.05.

NTHi-Induced Expression of hBD-2 and S100A7 Is Altered in COPD ALI-PBEC

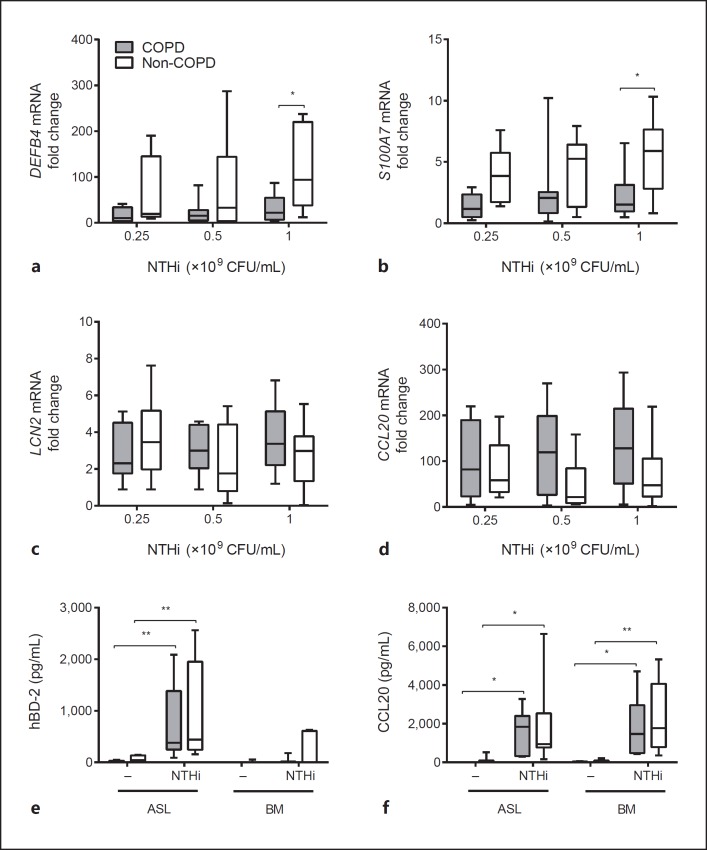

To investigate the role of AMPs in the reduced antibacterial activity of COPD airway epithelial cells, we examined the expression of microbial-induced AMPs in COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC exposed to various concentrations of UV-inactivated NTHi for 24 h. For this analysis we first focused on microbial-induced AMPs that were found to be highly expressed in submerged cultured and undifferentiated PBEC upon exposure to UV-inactivated NTHi, based on a microarray gene expression analysis (see online suppl. Table S1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000455193). These genes included DEFB4, encoding hBD-2, the antimicrobial chemokine CCL20, S100A7, lipocalin 2 (LCN2), and S100A7[23, 24, 25, 26]. NTHi stimulation induced the expression of all examined genes in both COPD and non-COPD cultures (Fig. 2a-d). However, COPD ALI-PBEC displayed lower NTHi-mediated expression of DEFB4 and S100A7 compared to non-COPD cultures (Fig. 2a, b), whereas LCN2 and CCL20 did not reveal statistically significant differences (Fig. 2c, d). We also did not observe differences in the expression of other AMPs that were not observed in the microarray gene expression analysis (LL-37/CAMP, SLPI, β-defensin 1 and 3 [hBD-1 and hBD-3]; see online suppl. Fig. S1). We further analyzed the NTHi-induced protein secretion of hBD-2 and CCL20 in apical washes and basal medium of COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC 24 h after stimulation. In contrast to the mRNA expression, we did not detect a difference in hBD-2 peptide release at the apical surface and basal medium between COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC (Fig. 2e, f). Moreover, no differences were observed in secretion of CCL20. To explain this discrepancy between hBD-2 mRNA expression and peptide levels, we examined whether the difference in mRNA expression was time dependent. Indeed, in contrast to NTHi-induced mRNA expression at 24 h, we did not detect differences between COPD and non-COPD at 3 and 12 h of stimulation (Fig. 3a-d). These findings suggest that the attenuated antibacterial defense of COPD airway epithelial cells observed 48 h after microbial stimulation was not accompanied by differences in the early effects of microbial stimuli on AMP expression, but possibly related to the lower expression of hBD-2 and S100A7 in COPD cultures only at later time points.

Fig. 2.

AMP expression by COPD ALI-PBEC is lower compared to non-COPD. COPD (gray boxplots, n = 12 patients) and non-COPD (white boxplots, n = 8 patients) ALI-PBEC were stimulated with different concentrations of UV-inactivated NTHi for 24 h. mRNA expression of the AMPs DEFB4/hBD-2 (a), S100A7 (b), LCN2 (c), and CCL20 (d) was assessed by qPCR. Stimulations were performed in duplicate. Data are shown as the fold change in mRNA compared to untreated cells. Assessment of hBD-2 (e) and CCL20 (f) protein secretion in the apical surface liquid (ASL) and basal medium (BM) of COPD (gray boxplots, n = 9) and non-COPD (white boxplots, n = 7–8) ALI-PBEC stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi for 24 h. Stimulations were performed in duplicate. Results are shown as boxplots with whiskers from minimum to maximum or bars (means ± SEM). The analysis of differences was conducted with a 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Fig. 3.

Differences in early- and late-induced transcriptional responses between COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC. Time course of NTHi-induced mRNA expression in COPD (gray bars, n = 12) and non-COPD AL-PBEC (white bars, n = 9). COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC were stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi for 3, 12, and 24 h, afterwards mRNA expression of DEFB4/hBD-2 (a), S100A7 (b), LCN2 (c), and CCL20 (d) was examined by qPCR. Stimulations were performed in duplicate. Data are shown as the fold change compared to unstimulated cells. All results are depicted as the mean ± SEM. The analysis of differences was conducted with an unpaired t test. * p < 0.05.

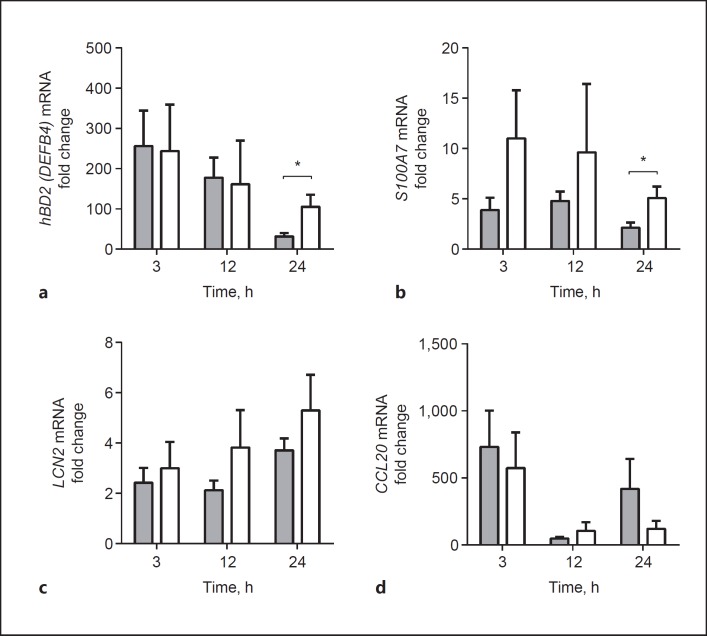

Cell Differentiation, Barrier Function and Expression of Regulatory Genes Do Not Differ between COPD and Non-COPD ALI-PBEC

We further studied the cause of the impaired expression of AMPs in COPD airway epithelial cells. Previous research has demonstrated a reduced host defense function of airway epithelial cells from severe COPD patients due to impaired cell differentiation [5, 27]. In addition, it was reported that COPD airway epithelial cells display a reduced barrier function [4]. Therefore, we examined cell differentiation and the epithelial barrier integrity of COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC. In contrast to previous findings, we did not observe differences in mRNA expression levels of the club cell marker SCGB1A1, ciliated cell marker FOXJ1, goblet cell marker MUC5AC, and basal cell marker TP63 (Fig. 4a-d). Moreover, we did not observe differences in the epithelial barrier function between COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC, based on TEER measurements (Fig. 4e). Furthermore, COPD ALI-PBEC did not display low TEER values as observed in a previous study [4]. These findings suggest that the altered NTHi-induced antibacterial defense of COPD airway epithelial cells is not caused by impaired cell differentiation or a reduced barrier function. Another possible explanation for the persistence of this difference after prolonged culture could be the presence of epigenetic modifications in the epithelium from COPD patients. These modifications can lead to a variety of changes that may help to explain the observed differences. First, this differential expression might be caused by altered expression of pattern recognition receptors at later time points. It has been shown that NTHi increases the expression of TLR2 [28], and impairment of this induction in cells from COPD patients can influence late-induced innate immune responses. However, we did not observe differences in TLR2 mRNA expression between COPD and non-COPD cultures (see online suppl. Fig. S2). Second, alterations in the negative-feedback loop mechanism of the NF-κB signaling pathway may also result in the impaired expression of AMPs, such as differential expression of micro-RNAs, like mir-147b, the deubiquitinating enzyme/ubiquitin ligase A20, or the transcription factor ATF3 [29, 30, 31]. However, we did not observe differences in the expression of the primary mir-147b transcript, and expression of A20 and ATF3 mRNA (see online suppl. Fig. S2). This suggests that other mechanisms underlie the altered microbial-induced expression of AMPs in COPD airway epithelial cultures.

Fig. 4.

Expression of epithelial differentiation markers and barrier function in COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC. Baseline mRNA expression of the cell differentiation markers SCGB1A1 (club cell; a), FOXJ1 (ciliated cell; b), MUC5AC (goblet cell; c), and TP63 (basal cell; d) was determined in differentiated ALI-PBEC from COPD (gray boxplots, n = 11 patients) and non-COPD (white boxplots, n = 8 patients) ALI-PBEC. Data are shown as normalized values. e The epithelial barrier integrity of COPD (gray boxplots, n = 9 patients) and non-COPD (white boxplots, n = 7 patients) ALI-PBEC was determined by measuring the TEER values. ALL results are shown as boxplots with whiskers from minimum to maximum or bars (means ± SEM). The analysis of differences was conducted with a 2-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test.

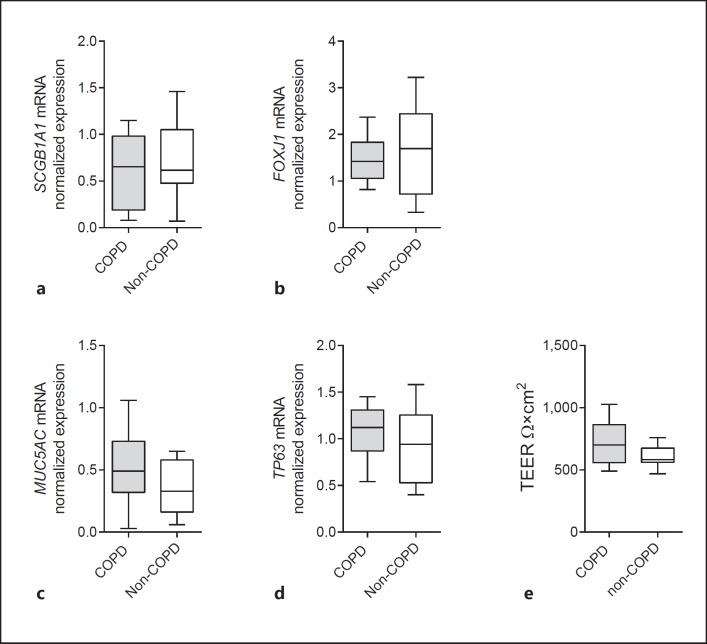

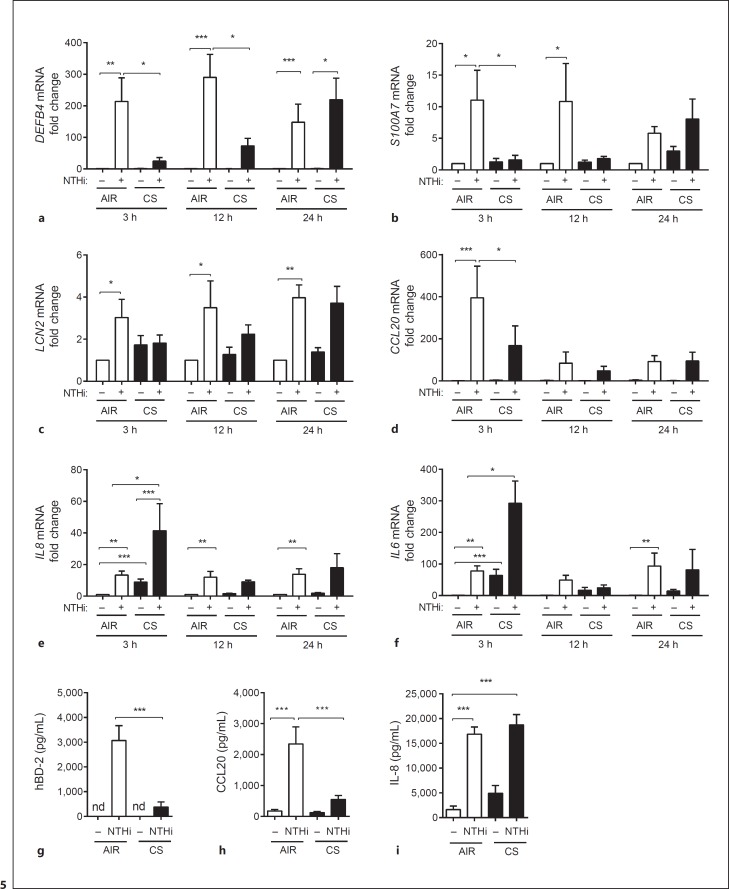

CS Differentially Affects the Induction of AMPs and Proinflammatory Mediators in ALI-PBEC

We next set out to investigate the effect of CS exposure on the expression of AMPs and proinflammatory mediators. This was done using a whole CS exposure model in which ALI-PBEC are exposed to mainstream smoke derived from 1 cigarette or AIR as a negative control. The exposure is for a period of 15 min, after which the cells are stimulated with UV-inactivated NTHi for 3, 12, and 24 h. After the indicated time points, mRNA expression was measured by qPCR. Corresponding with earlier reports [12, 13, 14], CS exposure significantly reduced the NTHi-mediated expression of DEFB4 at 3 and 12 h after exposure (Fig. 5a). This effect was no longer observed at 24 h after exposure. CS also attenuated the NTHi-induced expression of LCN2, S100A7, and CCL20 after 3 h (Fig. 5b-d). In accordance with preceding studies [14, 15], we observed a further increase in IL-8 and IL-6 mRNA expression upon CS and NTHi costimulation (Fig. 5e, f). We also found decreased NTHi-induced hBD-2 and CCL20 protein secretion in CS-exposed cultures (Fig. 5g, h), whereas IL-8 secretion was not attenuated and further enhanced (Fig. 6i). Overall, these data demonstrate that CS exposure differentially modulates microbial-induced innate immunity, impairing the induction of AMPs while increasing proinflammatory mediators.

Fig. 5.

CS differentially modulates the innate immune gene expression. ALI-PBEC (n = 7) were exposed to AIR or CS and subsequently stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi for 3, 12, and 24 h. mRNA expression of DEFB4 (a), S100A7 (b), LCN2 (c), CCL20 (d), IL8 (e), and IL6 (f) was measured by qPCR. Stimulations were performed in duplicate. Data are shown as the fold change in mRNA compared to untreated cells. Assessment of hBD-2 (g) secretion in the apical surface liquid and CCL20 (h) and IL-8 (i) secretion in the basal medium of AIR/CS-exposed ALI-PBEC (n = 7) stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi. Stimulations were performed in duplicate. All results are shown as the mean ± SEM. The analysis of differences was conducted with a 1-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test (a–f), and paired t test (g–i). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Fig. 6.

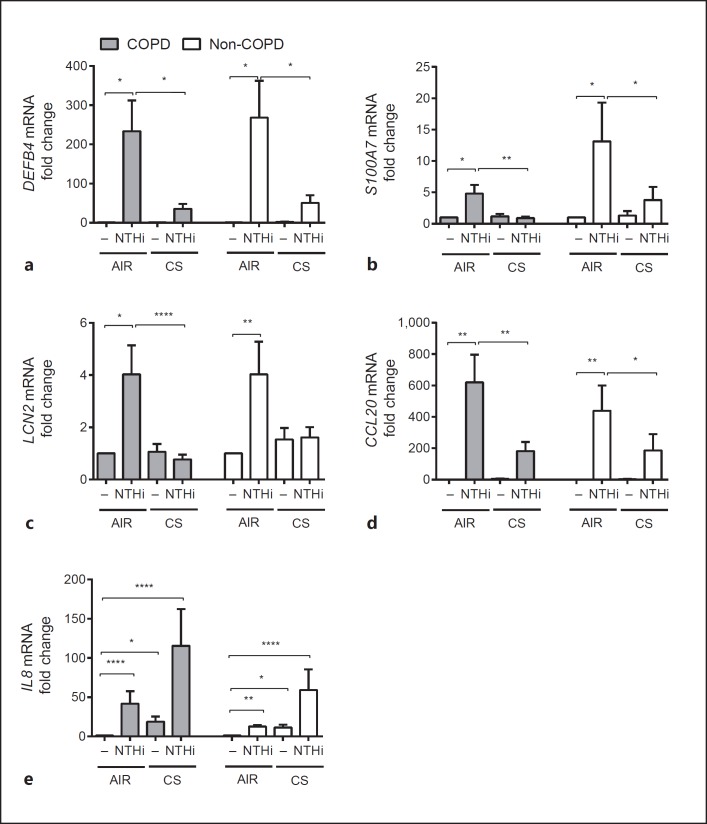

Suppression of AMPs by CS in both COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC. COPD (gray bars, n = 12 patients) and non-COPD (white bars, n = 8 patients) ALI-PBEC were exposure to AIR or CS and subsequently stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi for 3 h. mRNA expression of DEFB4 (a), S100A7 (b), LCN2 (c), CCL20 (d), and IL8 (e) was determined by qPCR. Stimulations were performed in duplicate. Data are shown as the fold change in mRNA compared to untreated cells and depicted as the mean ± SEM. The analysis of differences was conducted with a paired t test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001.

CS Impairs NTHi-Induced Expression of AMPs in Both COPD and Non-COPD ALI-PBEC

Next, we determined the effect of CS on COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC. As we observed an acute effect of CS exposure, which was primarily seen at 3 h after exposure, we studied the mRNA expression levels of AMPs at this particular time point. AMP expression was reduced by smoke in both COPD and non-COPD cultures, thus suggesting that the attenuation of AMP expression in our CS exposure model occurs independently of disease status (Fig. 6a-d). We did not observe a significant difference in IL-8 mRNA expression between CS- and NTHi-exposed COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC (Fig. 6e). This suggests that modulation of the expression of AMPs and proinflammatory mediators by CS occurs to a similar extent in COPD and non-COPD ALI-PBEC cultures.

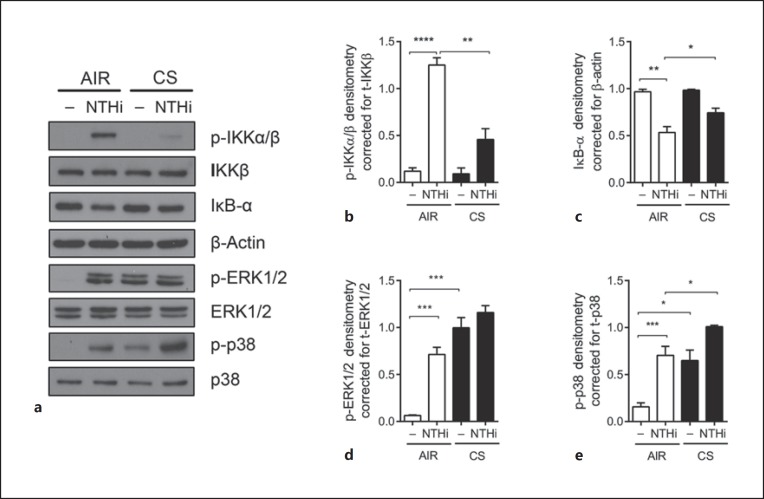

CS Inhibits NTHi-Mediated Activation of NF-κB but Not MAPK Signaling in ALI-PBEC

We subsequently examined the underlying mechanism of the differential regulation of AMPs and proinflammatory mediators by CS. Microbial- and cytokine-mediated expression of AMPs and proinflammatory mediators are regulated in particular by the NF-κB and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling pathways [16, 17]. Therefore, we examined the effect of CS exposure on NF-κB and MAPK signal transduction in ALI-PBEC. Epithelial cultures were exposed to CS or AIR as the control and subsequently stimulated with UV-inactivated NTHi at the apical surface for 30 min. Activation of NF-κB was determined by assessing the phosphorylation of the upstream NF-κB signaling kinases IKKα/β and degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor IκB-α. MAPK signaling was evaluated by assessing the phosphorylation of p38 and ERK1/2. The NTHi stimulation of AIR-exposed cultures resulted in the enhanced activation of NF-κB signal transduction based on the phosphorylation of IKKα/β and degradation of the NFκB inhibitor IκB-α (Fig. 7a-c). In contrast, CS exposure suppressed IKKα/β phosphorylation and IκB-α degradation. Both NTHi- and CS-induced phosphorylation of the MAPKs ERK1/2 and p38, and CS exposure did not attenuate the NTHi-mediated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 (Fig. 7a, d, e). These findings demonstrate that CS alters NF-κB and MAPK signaling, which corresponds with the attenuated expression of AMPs and enhanced expression of proinflammatory mediators.

Fig. 7.

CS impairs NTHi-induced NF-κB but not MAPK signal transduction in ALI-PBEC. a ALI-PBEC (n = 4–8) were exposed to AIR/CS and stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi for 30 min. NF-κB activation was assessed by measuring the phosphorylation of IKKα/β and degradation of IκB-α. MAPK signaling was assessed by determining the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38. b–e Analysis of the data by densitometry. Results are shown as the mean ± SEM. Analysis of differences was conducted with a paired t test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

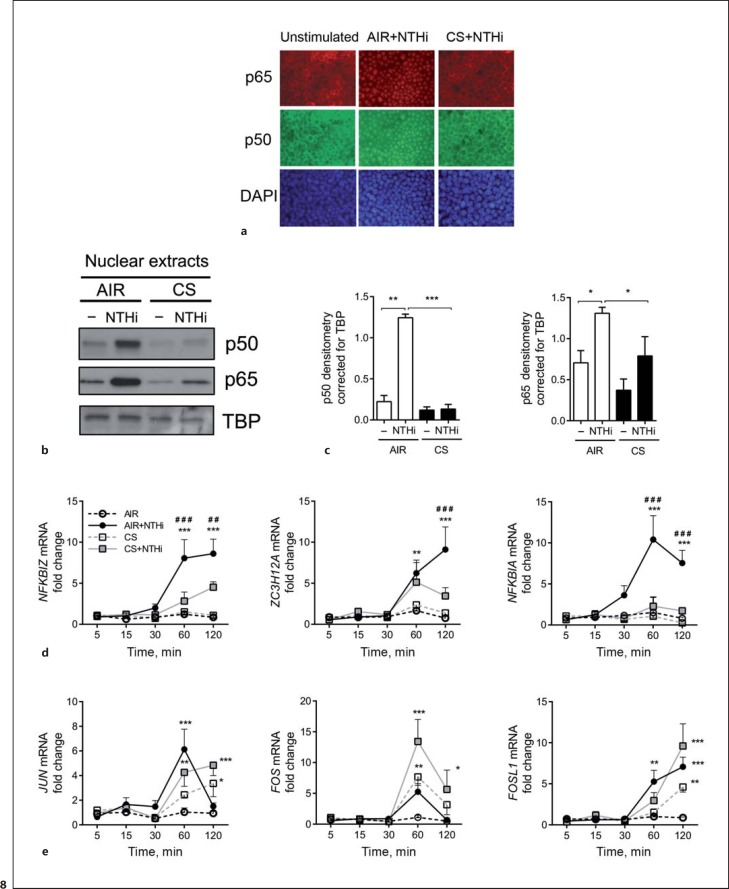

CS Suppresses NF-κB-Mediated Transcriptional Activity

To further assess whether alterations in NF-κB signaling correspond with reduced AMP expression, we investigated the nuclear translocation of NF-κB and transcription of early induced target genes. In agreement with impaired IκB-α degradation, CS inhibited nuclear translocation of the p50 and p65 NF-κB subunit, as shown by immunofluorescence staining and analysis of isolated nuclear fractions (Fig. 8a-c). To validate whether this reduced nuclear localization impaired NF-κB-mediated transcription, we examined the expression of early induced NF-κB-target genes, including the negative feedback regulators NFKBIA and ZC3H12A[32], and NFKBIZ, which represent an essential cotranscription factor required for AMP expression [33]. Moreover, the induction of MAPK-regulated early induced target genes and AP-1 transcription factors FOS, JUN, and FOSL1[34] was determined. CS exposure attenuated the NTHi-induced expression of NFKBIZ and NFKBIA at 60 and 120 min after stimulation, whereas induction of ZC3H12A was impaired at 120 min (Fig. 8d). In contrast, CS exposure further increased the induction of FOS at 60 and 120 min, and JUN and FOSL1 expression after 120 min of stimulation (Fig. 8e). Overall, these observations demonstrate the selective attenuation of NF-κB-mediated transcriptional activity by CS, which reflects an impaired expression of AMPs.

Fig. 8.

CS impairs NF-κB transcriptional activity by ALI-PBEC. ALI-PBEC were left untreated or exposed to AIR or CS and stimulated with UV-inactivated NTHi for 1 h. a Cellular localization of the NF-κB subunits p50 and p65 was determined by immunofluorescence microscopy. The data shown represent n = 3 independent donors. b ALI-PBEC (n = 4) were exposed to AIR or CS and stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi for 1 h. Protein expression of p50 and p65 was measured in isolated nuclear extracts. c The data were quantified by densitometry. ALI-PBEC were unstimulated or exposed to AIR or CS and stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/ml UV-inactivated NTHi for 1 h. ALI-PBEC (n = 4) were exposed to AIR or CS and subsequently stimulated with 1 × 109 CFU/mL UV-inactivated NTHi for 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min. mRNA expression of early induced NF-κB target genes NFKBIA, ZC3H12A, and NFKBIZ (d), and early induced MAPK-target genes JUN, FOS, and FOSL1 (e), was determined by qPCR. Data are shown as the fold change in mRNA compared to AIR-exposed cells. All results are shown as the mean ± SEM. Analysis of differences was conducted with a paired t test (c) and 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test (d, e). Significant differences compared to AIR: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Significant differences compared to CS+NTHi: ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001.

Discussion

In this study we have provided evidence that the antibacterial defense of airway epithelial cells from COPD patients is decreased compared to non-COPD (ex-)smokers. In addition, we have shown that the impairment of microbial-induced expression of AMPs by CS exposure may be related to the inhibition of NF-κB activation. The persistence of proinflammatory responses to microbial stimulation in the presence of CS may be explained by enhanced MAPK signaling.

In contrast to the impaired antibacterial activity of cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells at steady-state conditions [35, 36], COPD cultures only display an attenuated antibacterial activity upon microbial stimulation, suggesting that the induction of antibacterial factors is impaired. Indeed, a previous study reported lower hBD-2 expression in airway epithelial tissues from COPD patients compared to non-COPD (ex-)smokers [10]. In line with this study, we detected lowered NTHi-mediated expression of hBD-2/DEFB4 mRNA expression in cultured COPD airway epithelia. In addition, we also observed lower NTHi-induced S100A7 mRNA by COPD epithelial cultures. In contrast to hBD-2, S100A7 displays antibacterial activity by impairing bacterial acquisition of zinc [25], which suggests that the expression of AMPs with different modes of action is affected in COPD. In contrast to the differential regulation of DEFB4 at 24 h after NTHi stimulation, we did not observe differences in mRNA levels at earlier time points and protein secretion at 24 h. This suggests that COPD and non-COPD airway epithelial cells differ in late-induced mRNA expression.

It has been shown that ALI-PBEC cultures from severe COPD patients display impaired epithelial differentiation and epithelial barrier integrity, which causes an impaired host defense [4, 5, 27]. However, we did not observe differences in the mRNA expression of cell differentiation markers and the epithelial barrier function. It is therefore unlikely that altered epithelial differentiation is the underlying cause for the impaired antibacterial activity of COPD cultures observed in this study. In contrast to the airway epithelial cell cultures from mild-to-moderate COPD patients used in this study, impaired epithelial differentiation in severe COPD may have an additional impact on antibacterial host defense. Impaired differentiation may, for example, lead to a loss of CFTR expression, which in turn may result in impaired activity of AMPs in the airway surface liquid [37].

We further hypothesized that the differences in late-induced mRNA expression between COPD and non-COPD airway epithelial cells might be caused by the differential expression of second messengers, posttranscriptional and/or posttranslational mechanisms influencing these late-induced responses. TLR2, pri-mir-147b, A20, and ATF3 are known regulators of microbial-induced innate immune responses that might be affected in COPD cultures and thereby explain the impaired antibacterial defense. Despite of this, we did not observe differences in the NTHi-induced mRNA expression of these regulators.

Differences in the antibacterial activity between COPD and non-COPD cell cultures were determined with an assay previously used to assess the antibacterial activity of cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cell cultures [21, 36]. Conventional killing assays rely on the collection of apical washes or inoculation of bacteria to the apical surface that may, respectively, result in the selective collection of antimicrobial substances and dilution or modulation of the physiological conditions of the apical surface liquid. This could have a major influence on determining the antibacterial activity of epithelial cells, and the assay used in the present study is not affected by these factors.

Although it is tempting to speculate that a reduced antibacterial activity of COPD airway epithelial cells is due to a reduced expression of DEFB4 and S100A7, a clear link between these findings is missing. Indeed, other antibacterial defense mechanisms may also be affected in the epithelium of COPD patients, and contribute to the reduced antibacterial activity. In addition to various AMPs, antimicrobial lipids and reactive oxygen species also contribute to the bacterial killing activity of the airway epithelium [38, 39]. Moreover, lower antimicrobial activity might also result from other alterations in the airway surface liquid, such as a reduced pH, and the presence of mucins, F-actin, and proteoglycans [21, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44]. Therefore, we cannot exclude that changes in the presence or activity of other antibacterial mediators and changes in the composition of the airway surface liquid also contributed to the reduced antibacterial activity of the COPD airway epithelial cells.

In line with previous studies demonstrating reduced antibacterial activity and inhibition of hBD-2 expression caused by CS [12, 13, 14], we showed that the expression of S100A7, LCN2, and CCL20 was also inhibited in CS-exposed COPD and non-COPD cultures. In contrast to AMPs, we showed increased NTHi-induced expression of IL-8 and IL-6 upon CS exposure. This further demonstrates that AMPs and proinflammatory mediators are differentially regulated in airway epithelial cells. The modulation of innate immune responses by CS was primarily observed 3 h after exposure, which is in line with the transient effect of the acute exposure [14].

Our study has several limitations. Our findings are limited to the acute effects of microbes and CS on airway epithelial innate immune responses, and chronic exposures of airway epithelial cells to both NTHi and CS may cause different effects. Moreover, differences in the smoking status of both COPD and non-COPD subjects may have an influence on our findings. Current and ex-smokers were both included in the COPD and non-COPD group; however, we only have limited information about pack years smoked, for example. Further research regarding the influence of smoking status is therefore needed.

To assess whether alterations in AMPs and proinflammatory mediator expression are reflected by changes in cellular signal transduction pathways, we examined the effect of CS on NF-κB and MAPK signaling. Whereas CS increased MAPK signaling, it reduced NTHi-induced NF-κB signal transduction. NTHi-induced activation of MAPK and NF-κB is mediated by the common upstream signaling kinase TAK1, which directly phosphorylates IKKα/β [45]. Therefore, we speculate that CS causes selective suppression of NF-κB signaling by directly modulating IKKα/β phosphorylation, rather than affecting TAK1 or more upstream signaling components (see online suppl. Fig. S3). This appears in contrast to some studies that have reported increased NF-κB activation in COPD lung tissue [46, 47, 48]. However, this is not observed in all studies and it has been suggested that NF-κB signaling may not contribute to COPD pathogenesis [49]. Furthermore, our results are also in line with those of a study showing that long-term passive CS exposure inhibits UVB-induced NF-κB signaling in the skin [50], and with earlier reports showing impaired IKKα/β phosphorylation and kinase activity caused by posttranslational modifications, mediated for instance by oxidative stress [51, 52]. Previous studies demonstrated the importance of NF-κB in both microbial-induced hBD-2 and IL-8 by airway epithelial cells. However, our findings suggest a more fundamental role of NF-κB in the antibacterial defense, whereas induction of IL-8 and IL-6 persisted independent of NF-κB. Restoration of NF-κB signaling may therefore improve the airway epithelial antibacterial defense in smokers. However, further research is required to study this.

As also discussed in the previous section, the role of NF-κB in COPD remains a matter of debate since inflammation in COPD may occur independent of NF-κB [49]. Based on our findings, it can be speculated that MAPK signaling has a more prominent role in CS-induced airway epithelial inflammatory responses than NF-κB. This is further supported by findings from a recent study examining ozone-induced proinflammatory responses by differentiated airway epithelial cells, revealing the MAPK-dependent and NF-κB-independent induction of inflammatory mediators [53].

Our study focused on airway epithelial responses to NTHi because of the critical role of this microbe in COPD pathogenesis [54]. However, multiple respiratory pathogens are often isolated from the airways of COPD patients and these microorganisms may affect epithelial cell function in a different way than NTHi. In recent years there has been an increased awareness of the role of the microbiome in COPD development and progression [55]. CS-induced changes in airway epithelial defense may affect the composition of this microbiome, and its altered composition may contribute to COPD development and progression. We reported in a previous study that CS exposure increased the expression of the antimicrobial protein RNase 7 in ALI-PBEC cultures [14]. This raises the possibility that, in addition to a selective downregulation of microbial-induced AMPs, the expression of other AMPs might be increased by smoke exposure. These and other changes in airway epithelial defense may contribute to changes in the microbiome. However, further research is needed to study the role of AMPs in regulating the airway microbiome in COPD.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that cultured airway epithelial cells from COPD patients have reduced antibacterial activity. Moreover, we observed an imbalance between the protective antibacterial defense and destructive inflammatory innate immune response of airway epithelial cells from COPD patients in response to CS. This imbalance explains in part the enhanced bacterial burden and increased lung inflammation observed in COPD development and progression. Therefore, application of exogenous AMPs to compensate for the loss of AMPs might have therapeutic potential in COPD [56]. Furthermore, the differential regulation of AMPs and proinflammatory mediators at the signal transduction level suggests that selective therapeutic targeting of airway inflammation, without affecting the beneficial antibacterial defense, might be possible.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Annemarie van Schadewijk for her technical assistance, Winifred Broekman and Jorn Nützinger for help in collecting patient data, and the Department of Thoracic Surgery at LUMC for the collection of lung tissue. This work was supported by an unrestricted research grant from Galapagos NV, The Netherlands. H.P.H. was supported by a Program Grant (RGP001612009-C) of the Human Frontier Science Program.

References

- 1.Sethi S. Infection as a comorbidity of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1209–1215. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00081409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sethi S, Mallia P, Johnston SL. New paradigms in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease II. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:532–534. doi: 10.1513/pats.200905-025DS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arcavi L, Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and infection. Arch Int Med. 2004;164:2206–2216. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.20.2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heijink IH, Noordhoek JA, Timens W, van Oosterhout AJM, Postma DS. Abnormalities in airway epithelial junction formation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1439–1442. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-1982LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gohy ST, Detry BR, Lecocq Mn, Bouzin C, Weynand BA, Amatngalim GD, Sibille YM, Pilette C. Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor downregulation in COPD: persistence in the cultured epithelium and role of transforming growth factor-β. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:509–521. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201311-1971OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bals R, Hiemstra PS. Innate immunity in the lung: how epithelial cells fight against respiratory pathogens. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:327–333. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00098803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganz T. Antimicrobial polypeptides in host defense of the respiratory tract. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:693–697. doi: 10.1172/JCI15218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans SE, Xu Y, Tuvim MJ, Dickey BF. Inducible innate resistance of lung epithelium to infection. Annu Rev Physiol. 2010;72:413–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021909-135909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parameswaran GI, Sethi S, Murphy TF. Effects of bacterial infection on airway antimicrobial peptides and proteins in COPD. Chest. 2011;140:611–617. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pace E, Ferraro M, Minervini MI, Vitulo P, Pipitone L, Chiappara G, Siena L, Montalbano AM, Johnson M, Gjomarkaj M. Beta defensin-2 is reduced in central but not in distal airways of smoker COPD patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mallia P, Footitt J, Sotero R, Jepson A, Contoli M, Trujillo-Torralbo MB, Kebadze T, Aniscenko J, Oleszkiewicz G, Gray K, Message SD, Ito K, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM, Papi A, Stanciu LA, Elkin SL, Kon OM, Johnson M, Johnston SL. Rhinovirus infection induces degradation of antimicrobial peptides and secondary bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1117–1124. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0806OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herr C, Beisswenger C, Hess C, Kandler K, Suttorp N, Welte T, Schroeder JM, Vogelmeier C, Bals R. Suppression of pulmonary innate host defence in smokers. Thorax. 2009;64:144–149. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.102681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Case S, Bowler RP, Martin RJ, Jiang D, Hu HW. Cigarette smoke modulates PGE2 and host defence against Moraxella catarrhalis infection in human airway epithelial cells. Respirology. 2011;16:508–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amatngalim GD, van Wijck Y, de Mooij-Eijk Y, Verhoosel RM, Harder J, Lekkerkerker AN, Janssen RAJ, Hiemstra PS. Basal cells contribute to innate immunity of the airway epithelium through production of the antimicrobial protein RNase 7. J Immunol. 2015;194:3340–3350. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beisswenger C, Platz J, Seifart C, Vogelmeier C, Bals R. Exposure of differentiated airway epithelial cells to volatile smoke in vitro. Respiration. 2004;71:402–409. doi: 10.1159/000079647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang BC, Lim KJ, Paik JH, Kwon YK, Shin SW, Kim SC, Jung TY, Kwon TK, Cho JW, Baek WK, Kim SP, Suh MH, Suh SI. Up-regulation of human β-defensin 2 by interleukin-1β in A549 cells: involvement of PI3K, PKC, p38 MAPK, JNK, and NF-κB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:1026–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bezzerri V, Borgatti M, Finotti A, Tamanini A, Gambari R, Cabrini G. Mapping the transcriptional machinery of the IL-8 gene in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:6069–6081. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Wetering S, Zuyderduyn S, Ninaber DK, van Sterkenburg MAJA, Rabe KF, Hiemstra PS. Epithelial differentiation is a determinant in the production of eotaxin-2 and -3 by bronchial epithelial cells in response to IL-4 and IL-13. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agusti AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ, Nishimura M, Stockley RA, Sin DD, Rodriguez-Roisin R. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groeneveld K, van Alphen L, Eijk PP, Visschers G, Jansen HM, Zanen HC. Endogenous and exogenous reinfections by Haemophilus influenzae in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the effect of antibiotic treatment on persistence. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:512–517. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pezzulo AA, Tang XX, Hoegger MJ, Abou Alaiwa MH, Ramachandran S, Moninger TO, Karp PH, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Haagsman HP, van Eijk M, Banfi B, Horswill AR, Stoltz DA, McCray PB, Welsh MJ, Zabner J. Reduced airway surface pH impairs bacterial killing in the porcine cystic fibrosis lung. Nature. 2012;487:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Proud D, Sanders SP, Wiehler S. Human rhinovirus infection induces airway epithelial cell production of human β-defensin 2 both in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:4637–4645. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh PK, Jia HP, Wiles K, Hesselberth J, Liu L, Conway BA, Greenberg EP, Valore EV, Welsh MJ, Ganz T, Tack BF, McCray PB. Production of β-defensins by human airway epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14961–14966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Starner TD, Barker CK, Jia HP, Kang Y, McCray PB. CCL20 is an inducible product of human airway epithelia with innate immune properties. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:627–633. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0272OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glaser R, Harder J, Lange H, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroder JM. Antimicrobial psoriasin (S100A7) protects human skin from Escherichia coli infection. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:57–64. doi: 10.1038/ni1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flo TH, Smith KD, Sato S, Rodriguez DJ, Holmes MA, Strong RK, Akira S, Aderem A. Lipocalin 2 mediates an innate immune response to bacterial infection by sequestrating iron. Nature. 2004;432:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gohy ST, Hupin C, Fregimilicka C, Detry BR, Bouzin C, Gaide Chevronay H, Lecocq Mn, Weynand B, Ladjemi MZ, Pierreux CE, Birembaut P, Polette M, Pilette C. Imprinting of the COPD airway epithelium for dedifferentiation and mesenchymal transition. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:1258–1272. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00135814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mikami F, Lim JH, Ishinaga H, Ha UH, Gu H, Koga T, Jono H, Kai H, Li JD. The Transforming growth factor-β-Smad3/4 signaling pathway acts as a positive regulator for TLR2 induction by bacteria via a dual mechanism involving functional cooperation with NF-κB and MAPK phosphatase 1-dependent negative cross-talk with p38 MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22397–22408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu G, Friggeri A, Yang Y, Park YJ, Tsuruta Y, Abraham E. miR-147, a microRNA that is induced upon Toll-like receptor stimulation, regulates murine macrophage inflammatory responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15819–15824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901216106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boone DL, Turer EE, Lee EG, Ahmad RC, Wheeler MT, Tsui C, Hurley P, Chien M, Chai S, Hitotsumatsu O, McNally E, Pickart C, Ma A. The ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20 is required for termination of Toll-like receptor responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1052–1060. doi: 10.1038/ni1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilchrist M, Thorsson V, Li B, Rust AG, Korb M, Kennedy K, Hai T, Bolouri H, Aderem A. Systems biology approaches identify ATF3 as a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 4. Nature. 2006;441:173–178. doi: 10.1038/nature04768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwasaki H, Takeuchi O, Teraguchi S, Matsushita K, Uehata T, Kuniyoshi K, Satoh T, Saitoh T, Matsushita M, Standley DM, Akira S. The IκB kinase complex regulates the stability of cytokine-encoding mRNA induced by TLR-IL-1R by controlling degradation of regnase-1. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1167–1175. doi: 10.1038/ni.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kao CY, Kim C, Huang F, Wu R. Requirements for two proximal NF-κB binding sites and I-κB-ζ in IL-17A-induced human β- defensin 2 expression by conducting airway epithelium. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15309–15318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708289200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith JJ, Travis SM, Greenberg EP, Welsh MJ. Cystic fibrosis airway epithelia fail to kill bacteria because of abnormal airway surface fluid. Cell. 1996;85:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shah VS, Meyerholz DK, Tang XX, Reznikov L, Abou Alaiwa M, Ernst SE, Karp PH, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Heilmann KP, Leidinger MR, Allen PD, Zabner J, McCray PB, Ostedgaard LS, Stoltz DA, Randak CO, Welsh MJ. Airway acidification initiates host defense abnormalities in cystic fibrosis mice. Science. 2016;351:503–507. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puchelle E, Zahm JM, Tournier JM, Coraux C. Airway epithelial repair, regeneration, and remodeling after injury in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:726–733. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-126SF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Do TQ, Moshkani S, Castillo P, Anunta S, Pogosyan A, Cheung A, Marbois B, Faull KF, Ernst W, Chiang SM, Fujii G, Clarke CF, Foster K, Porter E. Lipids including cholesteryl linoleate and cholesteryl arachidonate contribute to the inherent antibacterial activity of human nasal fluid. J Immunol. 2008;181:4177–4187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moskwa P, Lorentzen D, Excoffon KJDA, Zabner J, McCray PB, Nauseef WM, Dupuy C, Bánfi B. A novel host defense system of airways is defective in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:174–183. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-1029OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abou Alaiwa MH, Reznikov LR, Gansemer ND, Sheets KA, Horswill AR, Stoltz DA, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. pH modulates the activity and synergism of the airway surface liquid antimicrobials β-defensin-3 and LL-37. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:18703–18708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422091112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Felgentreff K, Beisswenger C, Griese M, Gulder T, Bringmann G, Bals R. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin interacts with airway mucus. Peptides. 2006;27:3100–3106. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiner DJ, Bucki R, Janmey PA. The antimicrobial activity of the cathelicidin LL37 is inhibited by F-actin bundles and restored by gelsolin. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:738–745. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0191OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baranska-Rybak W, Sonesson A, Nowicki R, Schmidtchen A. Glycosaminoglycans inhibit the antibacterial activity of LL-37 in biological fluids. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:260–265. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bergsson G, Reeves EP, McNally P, Chotirmall SH, Greene CM, Greally P, Murphy P, O'Neill SJ, McElvaney NG. LL-37 complexation with glycosaminoglycans in cystic fibrosis lungs inhibits antimicrobial activity, which can be restored by hypertonic saline. J Immunol. 2009;183:543–551. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shuto T, Xu H, Wang B, Han J, Kai H, Gu XX, Murphy TF, Lim DJ, Li JD. Activation of NF-KB by nontypeable Hemophilus influenzae is mediated by toll-like receptor 2-TAK1-dependent NIK-IKKα/β-IκBα and MKK3/6-P38MAP kinase signaling pathways in epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8774–8779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151236098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Di Stefano A, Caramori G, Oates T, Capelli A, Lusuardi M, Gnemmi I, Ioli F, Chung KF, Donner CF, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Increased expression of nuclear factor-κB in bronchial biopsies from smokers and patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:556–563. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00272002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Szulakowski P, Crowther AJL, Jiménez LA, Donaldson K, Mayer R, Leonard TB, MacNee W, Drost EM. The effect of smoking on the transcriptional regulation of lung inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:41–50. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-725OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yagi O, Aoshiba K, Nagai A. Activation of nuclear factor-κB in airway epithelial cells in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2006;73:610–616. doi: 10.1159/000090050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rastrick JMD, Stevenson CS, Eltom S, Grace M, Davies M, Kilty I, Evans SM, Pasparakis M, Catley MC, Lawrence T, Adcock IM, Belvisi MG, Birrell MA. Cigarette smoke induced airway inflammation is independent of NF-κB signalling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gottipati KR, Poulsen H, Starcher B. Passive cigarette smoke exposure inhibits ultraviolet light B-induced skin tumors in SKH-1 hairless mice by blocking the nuclear factor kappa B signalling pathway. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:780–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korn SH, Wouters EFM, Vos N, Janssen-Heininger YMW. Cytokine-induced activation of nuclear factor-κB is inhibited by hydrogen peroxide through oxidative inactivation of IκB kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35693–35700. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reynaert NL, Ckless K, Korn SH, Vos N, Guala AS, Wouters EFM, van der Vliet A, Janssen-Heininger YMW. Nitric oxide represses inhibitory κB kinase through S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8945–8950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400588101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCullough SD, Duncan KE, Swanton SM, Dailey LA, Diaz-Sanchez D, Devlin RB. Ozone induces a proinflammatory response in primary human bronchial epithelial cells through mitogen-activated protein kinase activation without nuclear factor-κB activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2014;51:426–435. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0515OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murphy TF, Brauer AL, Schiffmacher AT, Sethi S. Persistent colonization by Haemophilus influenzae in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:266–272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200403-354OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mammen MJ, Sethi S. COPD and the microbiome. Respirology. 2016;21:590–599. doi: 10.1111/resp.12732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hiemstra PS, Amatngalim GD, van der Does AM, Taube C. Antimicrobial peptides and innate lung defenses: role in infectious and noninfectious lung diseases and therapeutic applications. Chest. 2016;149:545–551. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data