Abstract

Background

Underuse of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation (AF) is an international problem, which has often been attributed to the presence of contraindications to treatment. No studies have assessed the influence of contraindications on anticoagulant prescribing in the UK.

Aim

To determine the influence of contraindications on anticoagulant prescribing in patients with AF in the UK.

Design and setting

Cross-sectional analysis of primary care data from 645 general practices contributing to The Health Improvement Network, a large UK database of electronic primary care records.

Method

Twelve sequential cross-sectional analyses were carried out from 2004 to 2015. Patients with a diagnosis of AF aged ≥35 years and registered for at least 1 year were included. Outcome measure was prescription of anticoagulant medication.

Results

Over the 12 study years, the proportion of eligible patients with AF with contraindications who were prescribed anticoagulants increased from 40.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 38.3 to 41.9) to 67.2% (95% CI = 65.6 to 68.8), and the proportion of those without contraindications prescribed anticoagulants increased from 42.1% (95% CI = 41.6 to 42.6) to 67.7% (95% CI = 67.2 to 68.1). In patients with a recent history of major bleeding or aneurysm, prescribing rates increased from 44.3% (95% CI = 42.2 to 46.5) and 34.8% (95% CI = 29.4 to 40.6) in 2004 to 71.7% (95% CI = 69.9 to 73.5) and 63.2% (95% CI = 58.3 to 67.8) in 2015, respectively, comparable with rates in patients without contraindications.

Conclusion

The presence or absence of recorded contraindications has little influence on the decision to prescribe anticoagulants for the prevention of stroke in patients with AF. The study analysis suggests that, nationally, 38 000 patients with AF with contraindications are treated with anticoagulants. This has implications for patient safety.

Keywords: anticoagulants; atrial fibrillation; contraindications; general practice; stroke, prevention; therapeutics

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia and it is associated with a substantial increase in risk of ischaemic stroke.1,2 Stroke risk is reduced by the use of anticoagulants.3–8

Anticoagulant prophylaxis has been recommended by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology since 1998 for patients with AF at elevated risk of stroke, and by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) since 2006.9–11 In the UK, rates of anticoagulation remain low;12–14 however, European studies suggest that high rates (>80%) of anticoagulation can be achieved.15,16

Underuse of anticoagulants is an international problem, which has often been attributed to the presence of contraindications to treatment, particularly bleeding or risk of bleeding.13,17–21 Conversely, however, several studies in the US and Europe have found similar rates of prescribing between patients with and without contraindications.22–24 To date, there have been no comparable studies carried out in the UK. Furthermore, there has been some inconsistency regarding which comorbidities are identified as contraindications to anticoagulant use. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) has defined contraindications to warfarin as: hypersensitivity to warfarin; haemorrhagic stroke; significant bleeding; pregnancy; within 72 hours of major surgery with risk of severe bleeding; within 48 hours postpartum; and drugs where interactions may lead to a significantly increased risk of bleeding.25 In many studies, other comorbidities, such as risk of falls, and possible compliance issues are often included as contraindications; these may be better regarded as cautions for anticoagulant treatment rather than as absolute contraindications.25,26

The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between contraindications and anticoagulant prescribing for AF in UK patients in primary care between 2004 and 2015.

METHOD

Data source

The Health Improvement Network is a database of anonymised electronic primary care records from UK general practices using Vision software. It includes coded data on patient characteristics, prescriptions, consultations, diagnoses, and primary care investigations for 3.6 million active patients registered at 587 active practices across the UK, with more than 85 million patient years of data.27 Practices were eligible for inclusion in the study from the latest of the practice acceptable mortality recording date,28 the Vision installation date, and the study start date (1 year prior to the first index date).

Study design

Twelve sequential cross-sectional analyses were performed on 1 May each year from 2004 to 2015 (index dates). All analyses were undertaken using Stata (version 13).

How this fits in

Underuse of anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation (AF) is well recognised internationally and is often attributed to the presence of contraindications. However, to date, no analysis has investigated the extent to which contraindications influence anticoagulant prescribing in the UK. This study indicates that contraindications, as defined in UK guidance, have little influence on the clinician’s decision to prescribe anticoagulants to patients with AF with moderate to high stroke risk. This has important implications for patient safety.

Analysis

Patients with a diagnosis of AF aged ≥35 years on the index date and registered at least 1 year prior to the index date were included in the analysis. The exposure of interest was the presence of contraindications to anticoagulants. Outcome was treatment with anticoagulants.

On each index date, the proportion of patients with AF with contraindications and the proportions of eligible patients prescribed anticoagulants with and without contraindications were calculated, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). P-values for trends over time were calculated using χ2 tests; P-values for differences between proportions of binary variables were calculated using two-sample tests for proportions. In primary analysis, patients with a CHADS2 score ≥1 (moderate or high stroke risk) were categorised as eligible for anticoagulant treatment. CHADS2 score was used to define eligibility as it has been in use for longer than CHA2DS2-VASc;29,30 in sensitivity analysis, patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥1 were categorised as eligible for anticoagulants.

Definitions of variables

A diagnosis of AF was defined by the presence of a clinical code for atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter at any time prior to the index date, excluding patients with a more recent clinical code indicating that AF had resolved. Current anticoagulant treatment was defined by a record of a relevant prescription within 90 days prior to the index date or a clinical code indicating the patient was receiving anticoagulant therapy within 365 days prior to the index date.

Contraindications to anticoagulants were defined in accordance with MHRA and NICE evidence.25,26 Contraindications specific to anticoagulants other than warfarin, such as novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) (for example, liver disease), were not included, as these do not preclude treatment with warfarin. Short-term contraindications (within 72 hours of surgery or 48 hours postpartum) and cautions for anticoagulant use were not included. Contraindications were defined as: a clinically coded diagnosis within the 2 years prior to the index date of haemorrhagic stroke, major bleeding (gastrointestinal, intracranial, intraocular, retroperitoneal), bleeding disorders (haemophilia, other haemorrhagic disorders, thrombocytopenia), peptic ulcer, oesophageal varices, aneurysm, or proliferative retinopathy; a record of allergy or adverse reaction to anticoagulants ever prior to the index date; a record of pregnancy in the 9 months prior to the index date; or severe hypertension with a mean (of the three most recent measures in the last 3 years prior to the index date) systolic blood pressure >200 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >120 mmHg.

CHADS2 scores were calculated by adding one point each for a history of congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years, and diabetes, and two points for a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA). CHA2DS2-VASc scores were calculated by adding one point each for a history of congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, vascular disease, age 65–74 years, and female sex (if another risk factor was present, otherwise 0), and two points each for age ≥75 years and history of stroke, TIA, or thromboembolism. History of congestive heart failure, stroke, TIA, thromboembolism, vascular disease, and diabetes were defined by a clinical code recorded ever prior to the index date, excluding patients with diabetes with a later record indicating diabetes resolved. Hypertension was defined as either a current (previous 90 days) prescription of antihypertensive drugs or the mean of the three most recent systolic blood pressures in the last 3 years ≥160 mmHg.

RESULTS

A total of 166 136 patients with AF from 645 practices were included in the study. As an individual could contribute to the analysis in more than 1 year, a total of 735 938 records of patients with AF were included in the analysis across the 12 index dates, with a median of 63 539 (interquartile range [IQR] = 56 696–67 571) patients per year. The mean age of patients with AF across all years was 76.2 (standard deviation [SD] 11.0) years; 54.7% (n = 402 354 out of 735 938) were male. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1: patients with AF with contraindications were on average 1.4 (95% CI = 1.3 to 1.5) years older and 2.3% (95% CI = 2.4 to 3.4) more were male.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic data of patients with atrial fibrillation with and without contraindications to anticoagulants, 2004–2015

| Year | Contraindications | Population n | Age mean (SD) | Sex male, % | Ethnicitya % | Townsend scoreb % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

| White | Asian | Black | Other | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Missing | |||||

| 2004 | Without | 42 358 | 75.4 (11.1) | 52.5 | 98.1 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 23.9 | 22.5 | 20.5 | 17.8 | 11.5 | 3.8 |

| With | 2971 | 76.7 (9.9) | 54.9 | 97.1 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 24.5 | 22.5 | 21.0 | 17.4 | 11.6 | 3.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2005 | Without | 47 892 | 75.5 (11.2) | 52.8 | 98.1 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 24.4 | 22.8 | 20.5 | 17.6 | 11.3 | 3.4 |

| With | 3280 | 76.8 (9.8) | 55.8 | 97.4 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 24.6 | 23.5 | 21.1 | 16.4 | 11.8 | 2.6 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2006 | Without | 52 437 | 75.6 (11.3) | 53.1 | 98.0 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 25.0 | 22.8 | 20.4 | 17.3 | 11.3 | 3.1 |

| With | 3502 | 76.7 (9.9) | 56.2 | 98.0 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 24.0 | 22.9 | 21.4 | 17.3 | 11.2 | 3.2 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2007 | Without | 55 008 | 76.0 (11.1) | 53.3 | 98.0 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 25.6 | 22.9 | 20.6 | 17.0 | 10.9 | 3.0 |

| With | 3487 | 77.1 (9.8) | 57.2 | 97.1 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 24.7 | 22.1 | 22.0 | 16.9 | 11.4 | 3.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2008 | Without | 57 916 | 76.1 (11.0) | 53.6 | 98.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 25.8 | 23.2 | 20.5 | 17.0 | 11.0 | 2.6 |

| With | 3610 | 77.4 (9.5) | 57.3 | 97.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 24.5 | 22.1 | 21.3 | 18.3 | 11.4 | 2.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2009 | Without | 61 583 | 76.2 (11.0) | 54.2 | 97.9 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 26.1 | 23.5 | 20.6 | 16.8 | 10.8 | 2.3 |

| With | 3969 | 77.7 (9.5) | 57.2 | 98.1 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 25.9 | 22.5 | 20.1 | 18.0 | 11.3 | 2.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2010 | Without | 62 421 | 76.2 (11.0) | 54.6 | 97.8 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 26.4 | 23.5 | 20.4 | 16.7 | 10.8 | 2.2 |

| With | 4024 | 77.4 (9.8) | 57.9 | 98.0 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 25.8 | 22.9 | 21.9 | 16.4 | 10.6 | 2.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2011 | Without | 64 090 | 76.3 (11.1) | 54.9 | 97.8 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 26.7 | 23.6 | 20.5 | 16.5 | 10.6 | 2.2 |

| With | 4103 | 77.7 (9.6) | 58.1 | 97.4 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 26.4 | 23.6 | 21.0 | 16.5 | 10.2 | 2.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2012 | Without | 65 405 | 76.3 (11.1) | 55.1 | 97.6 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 26.5 | 23.5 | 20.7 | 16.3 | 10.6 | 2.3 |

| With | 4248 | 77.9 (9.7) | 58.4 | 97.1 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 28.2 | 22.1 | 19.3 | 17.5 | 10.7 | 2.3 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2013 | Without | 64 985 | 76.2 (11.2) | 55.8 | 97.4 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 26.2 | 23.2 | 20.7 | 16.6 | 10.8 | 2.6 |

| With | 4248 | 77.8 (10.0) | 57.8 | 96.9 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 28.2 | 22.0 | 19.7 | 15.9 | 11.8 | 2.4 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2014 | Without | 62 855 | 76.3 (11.2) | 56.1 | 97.4 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 26.4 | 23.6 | 20.7 | 16.3 | 10.6 | 2.4 |

| With | 4093 | 78.0 (9.7) | 57.8 | 96.8 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 27.2 | 22.7 | 21.0 | 16.3 | 10.2 | 2.6 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| 2015 | Without | 54 100 | 76.2 (11.2) | 56.6 | 97.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 25.6 | 23.5 | 20.7 | 16.7 | 10.8 | 2.6 |

| With | 3353 | 77.8 (10.0) | 59.1 | 98.0 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 26.8 | 23.5 | 20.6 | 17.0 | 9.5 | 2.7 | |

Where recorded; ethnicity was missing in 59.2% of the patient records (decreasing from 74.4% in 2004 to 54.2% in 2015).

1 = Least deprived, 5 = Most deprived.

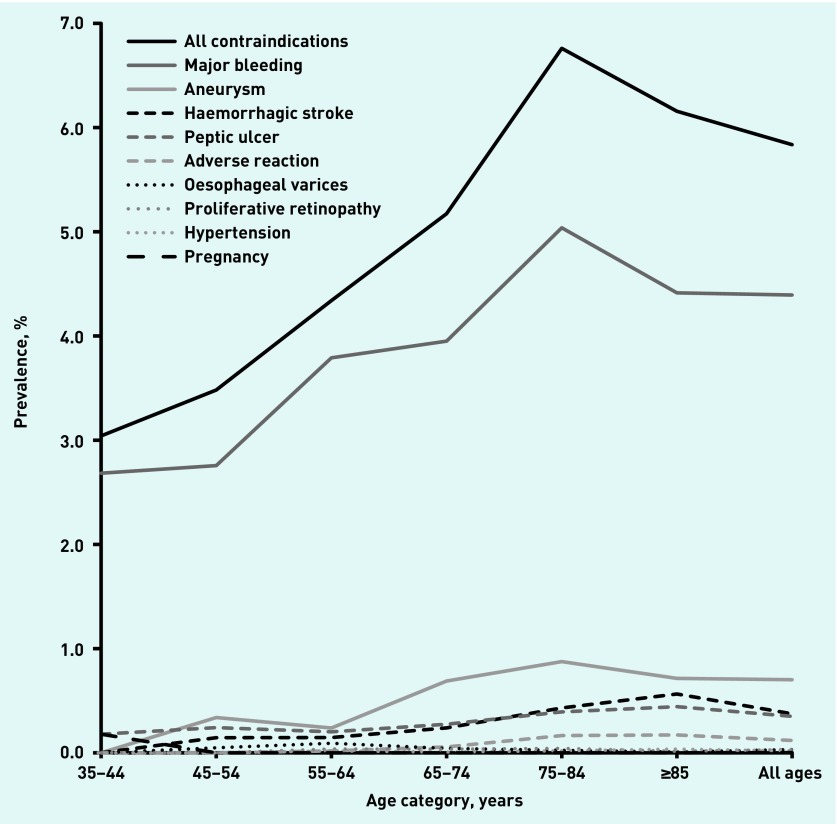

Around 6% of patients had contraindications to anticoagulation and this changed little over the 12-year period (range = 5.8 to 6.6%). The most common contraindication was major bleeding: 4.4% (95% CI = 4.2 to 4.6) of patients with AF in 2015. The prevalence of individual contraindications remained reasonably constant from 2004 to 2015, except for declining frequency of peptic ulcer from 0.64% to 0.35% (P<0.001) and of severe hypertension from 0.22% to 0.02% (P<0.001) (Appendix 1). The prevalence of all contraindications tended to increase with age (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of contraindications to anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation by age category, 2015.

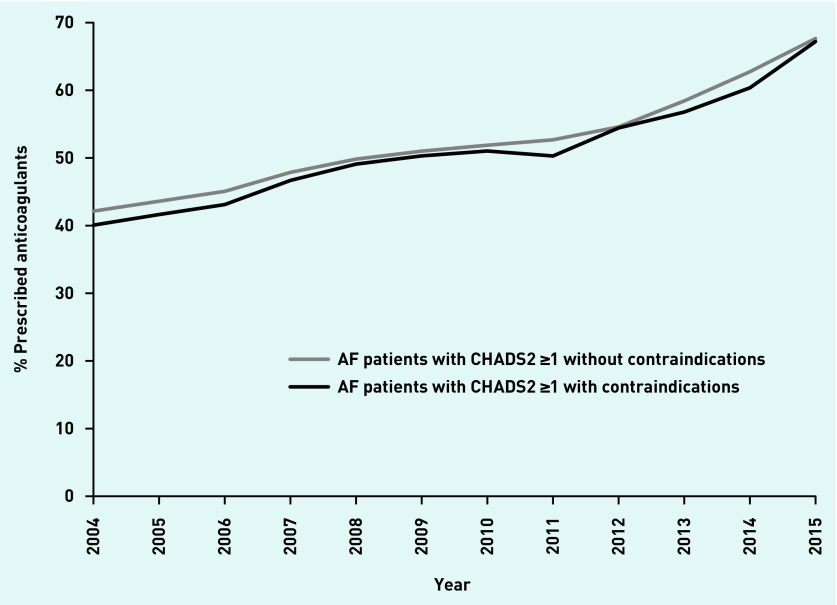

The proportion of eligible patients (with a CHADS2 score ≥1) prescribed anticoagulants increased from 2004 to 2015. However, in every year similar proportions with contraindications and without contraindications were prescribed anticoagulants (Figure 2). In 2004, 40.1% (95% CI = 38.3 to 41.9) of those with and 42.1% (95% CI = 41.6 to 42.6) of those without contraindications were prescribed anticoagulants; in 2015, this increased to 67.2% (95% CI = 65.6 to 68.8) and 67.7% (95% CI = 67.2 to 68.1), respectively (Appendix 2). The difference between the proportion of patients with and without contraindications who were prescribed anticoagulants in 2015 was not statistically significant: P = 0.595. In 2015, the interquartile range (IQR) for the proportion of eligible patients with AF prescribed anticoagulants by general practice was 52.6–80.0% in patients with contraindications and 61.8–72.4% in patients without contraindications.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with atrial fibrillation with and without contraindications who were prescribed anticoagulants, 2004–2015.

Defining eligibility for anticoagulants using the CHA2DS2-VASc score (≥1) made no difference to the observed trends or to differences in treatment between those with and without contraindications (Appendix 3).

The proportions of patients with AF who were prescribed anticoagulants, and trends in prescribing, were similar between patients with the most common contraindications — major bleeding and aneurysm — and patients without contraindications (Appendix 4). In eligible patients with AF with a recent history of major bleeding or aneurysm, prescribing rates increased from 44.3% (95% CI = 42.2 to 46.5) and 34.8% (95% CI = 29.4 to 40.6) in 2004 to 71.7% (95% CI = 69.9 to 73.5) and 63.2% (95% CI = 58.3 to 67.8) in 2015, respectively. These were comparable to prescribing rates in eligible patients with AF without contraindications: 42.1% (95% CI = 41.6 to 42.6) and 67.7% (95% CI = 67.2 to 68.1) in 2004 and 2015 respectively. The proportion of patients with AF with less common contraindications who were prescribed anticoagulants was lower across the whole period but also increased over time. In 2015, anticoagulants were prescribed to 44.1% (95% CI = 32.8 to 56.1) with an adverse reaction, 54.3% (95% CI = 47.5 to 61.0) with gastrointestinal disorders, 38.1% (95% CI = 31.9 to 44.8) with haemorrhagic stroke, 54.5% (95% CI = 25.6 to 80.7) with severe hypertension, and 83.3% (95% CI = 58.2 to 94.7) with proliferative retinopathy.

Treatment of patients with AF with NOACs began in 2010 and their use has increased steadily since then (Appendix 5). In 2015, slightly more patients with contraindications were prescribed NOACs than vitamin K antagonists: 19.0% versus 17.4% (P = 0.061).

DISCUSSION

Summary

This analysis demonstrates that patients with AF with contraindications are just as likely to be prescribed anticoagulants as those without contraindications. The proportion of patients with AF with contraindications who are prescribed anticoagulants is increasing over time, mirroring the rise in prescribing to those without contraindications. This suggests that, in practice, the presence or absence of most contraindications has little or no influence on the clinician’s decision to prescribe anticoagulants to patients with AF.

Strengths and limitations

The analysis was performed in a large general practice dataset that is generalisable to the UK population; the clinical data are routine and therefore comprise the information that GPs use for clinical decision making. AF diagnosis was often corroborated in the patient records, although it was not possible to confirm all diagnoses of AF; however, in a sample of 131 patients with AF diagnosed in UK primary care in 2006, 84% were found to have either a primary or secondary care electrocardiogram confirmation of their diagnosis.31 Care was taken to exclude patients with ‘AF resolved’.

Some anticoagulated patients may be omitted if they are managed entirely in hospital, and treatment rates may therefore be underestimated. However, this is attenuated by the inclusion of clinical codes for anticoagulant/international normalised ratio monitoring, in addition to prescription information, in the definition of anticoagulant use; furthermore, most anticoagulants are prescribed in primary care, and any underestimation is therefore likely to be small.

Most variables were defined by the presence of relevant clinical codes in the primary care record. Diagnoses that are part of the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework assessment are likely to be well recorded for most/all of the study period; clinically significant conditions, such as major bleed, which have important implications for prescribing of drugs other than anticoagulants, are also likely to be well recorded. However, recording of other medical conditions may be incomplete. There is no independent corroboration of the presence of contraindications, but the information used in the study is the same as that used by GPs for decision making, and contraindication rates are comparable with those found in other studies.16,23 Some contraindications may be inaccurate, for example, haemorrhagic stroke may be reclassified as ischaemic stroke; however, diagnosis of haemorrhagic stroke is generally accurate in primary care records.32 Some contraindications may be the result of previous anticoagulant treatment.

In addition to consideration of the presence/absence of contraindications, the decision to treat may also be influenced by cautions for anticoagulant use, such as the risk of falls or issues with treatment compliance. However, this should reduce rather than increase the likelihood of prescribing anticoagulants. Additionally, no information on patient preferences was available, although patients are often guided by GPs with regard to preventive medicine.33

Comparison with existing literature

Contraindications have often been cited as a reason for not prescribing anticoagulants.17,19–21 However, this analysis suggests that contraindications do not stop clinicians from prescribing; this agrees with findings from studies in the US and Europe.22–24 It is unclear why many patients with AF without contraindications are not prescribed anticoagulants, while patients with contraindications are.

Implications for research and practice

The study’s findings have important implications for patient care. Alongside underuse of anticoagulants in patients with AF, there may be significant overtreatment of patients with contraindications. Based on the recorded prevalence of AF in recent data there are 1.03 million UK patients diagnosed with AF.34,35 Of these, 59 000 (5.8%) have contraindications to anticoagulants, 57 000 (96%) of those with contraindications have a CHADS2 score ≥1, and 38 000 (67.2%) are treated. This represents a significant concern for patient safety.

Although the balance of risks and benefits of using anticoagulants is favourable in patients with AF who do not have contraindications, it is unclear whether this also applies to patients with contraindications. Further work is needed to determine whether outcomes are worse among contraindicated patients with AF who are treated with anticoagulants than among those who are not, or whether the reduced stroke risk offsets any other potential adverse events. There is some recent evidence suggesting that resuming anticoagulant therapy may be beneficial in patients with AF who survive warfarin-related intracranial haemorrhage.36,37

Further work is needed to determine which patients with contraindications may still benefit from anticoagulant treatment. Qualitative research is needed in order to reveal the reasons why clinicians prescribe to patients with contraindications and why they do not prescribe to many patients without.

Appendix 1. Prevalence of contraindications in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), 2004–2015

| Year | All AF (n) | Contraindications (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any | Adverse reaction | Peptic ulcer | Major bleeding | Haemorrhagic stroke | Hypertension | Oesophageal varices | Aneurysm | Proliferative retinopathy | Pregnancy | ||

| 2004 | 45 329 | 6.55 | 0.11 | 0.64 | 4.80 | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 2005 | 51 172 | 6.41 | 0.17 | 0.55 | 4.74 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| 2006 | 55 939 | 6.26 | 0.17 | 0.51 | 4.60 | 0.34 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| 2007 | 58 495 | 5.96 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 4.38 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| 2008 | 61 526 | 5.87 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 4.33 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| 2009 | 65 552 | 6.05 | 0.14 | 0.46 | 4.53 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 2010 | 66 445 | 6.06 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 4.58 | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| 2011 | 68 193 | 6.02 | 0.13 | 0.43 | 4.55 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| 2012 | 69 653 | 6.10 | 0.10 | 0.44 | 4.60 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| 2013 | 69 233 | 6.14 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 4.60 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.75 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| 2014 | 66 948 | 6.11 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 4.59 | 0.40 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.75 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| 2015 | 57 453 | 5.84 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 4.39 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

Appendix 2. Proportion of eligible (CHADS2 ≥1) patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) with and without contraindications prescribed anticoagulants, 2004–2015

| Year | Patients with AF without contraindications | Patients with AF with contraindications | P-value for difference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | CHADS2 ≥1 | Anticoagulants | All | CHADS2 ≥1 | Anticoagulants | ||||

| n | n | n | % (95% CI) | n | n | n | % (95% CI) | ||

| 2004 | 42 358 | 38 447 | 16 202 | 42.1 (41.6 to 42.6) | 2971 | 2795 | 1120 | 40.1 (38.3 to 41.9) | 0.0323 |

| 2005 | 47 892 | 43 692 | 19 051 | 43.6 (43.1 to 44.1) | 3280 | 3115 | 1297 | 41.6 (39.9 to 43.4) | 0.0325 |

| 2006 | 52 437 | 48 000 | 21 632 | 45.1 (44.6 to 45.5) | 3502 | 3331 | 1436 | 43.1 (41.4 to 44.8) | 0.0282 |

| 2007 | 55 008 | 51 008 | 24 416 | 47.9 (47.4 to 48.3) | 3487 | 3340 | 1559 | 46.7 (45.0 to 48.4) | 0.1821 |

| 2008 | 57 916 | 54 012 | 26 913 | 49.8 (49.4 to 50.2) | 3610 | 3455 | 1696 | 49.1 (47.4 to 50.8) | 0.3993 |

| 2009 | 61 583 | 57 689 | 29 424 | 51.0 (50.6 to 51.4) | 3969 | 3815 | 1919 | 50.3 (48.7 to 51.9) | 0.4002 |

| 2010 | 62 421 | 58 626 | 30 415 | 51.9 (51.5 to 52.3) | 4024 | 3855 | 1967 | 51.0 (49.4 to 52.6) | 0.3034 |

| 2011 | 64 090 | 60 259 | 31 745 | 52.7 (52.3 to 53.1) | 4103 | 3953 | 1988 | 50.3 (48.7 to 51.8) | 0.0036 |

| 2012 | 65 405 | 61 512 | 33 578 | 54.6 (54.2 to 55.0) | 4248 | 4104 | 2234 | 54.4 (52.9 to 56.0) | 0.8488 |

| 2013 | 64 985 | 60 995 | 35 640 | 58.4 (58.0 to 58.8) | 4248 | 4098 | 2327 | 56.8 (55.3 to 58.3) | 0.0384 |

| 2014 | 62 855 | 58 943 | 36 984 | 62.7 (62.4 to 63.1) | 4093 | 3956 | 2388 | 60.4 (58.8 to 61.9) | 0.0027 |

| 2015 | 54 100 | 50 677 | 34 286 | 67.7 (67.2 to 68.1) | 3353 | 3226 | 2168 | 67.2 (65.6 to 68.8) | 0.5947 |

Appendix 3. Proportion of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) with a CHA2DS2-VASc ≥1 score with and without contraindications prescribed anticoagulants, 2004–2015

| Patients with AF without contraindications | Patients with AF with contraindications | P-value for difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | CHA2DS2-VASc ≥1 | Anticoagulants | All | CHA2DS2-VASc ≥1 | Anticoagulants | ||||

| Year | n | n | n | % (95% CI) | n | n | n | % (95% CI) | |

| 2004 | 42 358 | 40 309 | 16 848 | 41.8 (41.3 to 42.3) | 2971 | 2897 | 1164 | 40.2 (38.4 to 42.0) | 0.0881 |

| 2005 | 47 892 | 45 632 | 19 747 | 43.3 (42.8 to 43.7) | 3280 | 3207 | 1340 | 41.8 (40.1 to 43.5) | 0.0994 |

| 2006 | 52 437 | 50 020 | 22 338 | 44.7 (44.2 to 45.1) | 3502 | 3428 | 1484 | 43.3 (41.6 to 45.0) | 0.1191 |

| 2007 | 55 008 | 52 949 | 25 192 | 47.6 (47.2 to 48.0) | 3487 | 3418 | 1595 | 46.7 (45.0 to 48.3) | 0.3002 |

| 2008 | 57 916 | 55 925 | 27 677 | 49.5 (49.1 to 49.9) | 3610 | 3549 | 1741 | 49.1 (47.4 to 50.7) | 0.6165 |

| 2009 | 61 583 | 59 569 | 30 147 | 50.6 (50.2 to 51.0) | 3969 | 3922 | 1973 | 50.3 (48.7 to 51.9) | 0.7135 |

| 2010 | 62 421 | 60 383 | 31 080 | 51.5 (51.1 to 51.9) | 4024 | 3956 | 2017 | 51.0 (49.4 to 52.5) | 0.5538 |

| 2011 | 64 090 | 62 042 | 32 361 | 52.2 (51.8 to 52.6) | 4103 | 4047 | 2019 | 49.9 (48.3 to 51.4) | 0.0051 |

| 2012 | 65 405 | 63 342 | 34 169 | 53.9 (53.6 to 54.3) | 4248 | 4187 | 2261 | 54.0 (52.5 to 55.5) | 0.9431 |

| 2013 | 64 985 | 62 813 | 36 220 | 57.7 (57.3 to 58.0) | 4248 | 4184 | 2363 | 56.5 (55.0 to 58.0) | 0.1328 |

| 2014 | 62 855 | 60 690 | 37 535 | 61.8 (61.5 to 62.2) | 4093 | 4040 | 2425 | 60.0 (58.5 to 61.5) | 0.0210 |

| 2015 | 54 100 | 52 189 | 34 844 | 66.8 (66.4 to 67.2) | 3353 | 3296 | 2196 | 66.6 (65.0 to 68.2) | 0.8697 |

Appendix 4. Proportions of patients with atrial fibrillation with specific contraindications and a CHADS2 score ≥1 who were prescribed anticoagulants, 2004–2015

| Year | No contraindications | Any contraindication | Major bleeding | Haemorrhagic stroke | Aneurysm | Proliferative retinopathy | Severe hypertension | Gastrointestinal disordersa | Adverse reaction | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | N | % (95% CI) | |

| 2004 | 38 447 | 42.1 (41.6 to 42.6) | 2795 | 40.1 (38.3 to 41.9) | 2037 | 44.3 (42.2 to 46.5) | 141 | 24.1 (17.7 to 31.9) | 279 | 34.8 (29.4 to 40.6) | 18 | 33.3 (15.4 to 57.9) | 97 | 22.7 (15.4 to 32.1) | 286 | 25.9 (21.1 to 31.3) | 47 | 27.7 (16.7 to 42.2) |

| 2005 | 43 692 | 43.6 (43.1 to 44.1) | 3115 | 41.6 (39.9 to 43.4) | 2290 | 45.4 (43.4 to 47.5) | 169 | 27.8 (21.6 to 35.1) | 326 | 38.0 (32.9 to 43.4) | 26 | 46.2 (28.0 to 65.4) | 77 | 22.1 (14.1 to 32.8) | 285 | 25.3 (20.5 to 30.6) | 85 | 25.9 (17.6 to 36.3) |

| 2006 | 48 000 | 45.1 (44.6 to 45.5) | 3331 | 43.1 (41.4 to 44.8) | 2428 | 46.6 (44.6 to 48.6) | 190 | 25.3 (19.6 to 31.9) | 383 | 41.5 (36.7 to 46.5) | 26 | 42.3 (24.9 to 61.9) | 60 | 31.7 (21.1 to 44.5) | 286 | 26.9 (22.1 to 32.4) | 93 | 29.0 (20.7 to 39.1) |

| 2007 | 51 008 | 47.9 (47.4 to 48.3) | 3340 | 46.7 (45.0 to 48.4) | 2440 | 50.9 (48.9 to 52.8) | 191 | 31.9 (25.7 to 38.9) | 392 | 43.4 (38.5 to 48.3) | 22 | 45.5 (26.0 to 66.4) | 50 | 36.0 (23.9 to 50.2) | 280 | 26.4 (21.6 to 31.9) | 89 | 27.0 (18.7 to 37.2) |

| 2008 | 54 012 | 49.8 (49.4 to 50.2) | 3455 | 49.1 (47.4 to 50.8) | 2537 | 53.1 (51.1 to 55.0) | 182 | 30.8 (24.5 to 37.9) | 408 | 46.3 (41.5 to 51.2) | 22 | 54.5 [33.6 to 74.0) | 38 | 26.3 (14.6 to 42.6) | 296 | 31.8 (26.7 to 37.3) | 99 | 34.3 (25.6 to 44.3) |

| 2009 | 57 689 | 51.0 (50.6 to 51.4) | 3815 | 50.3 (48.7 to 51.9) | 2839 | 54.6 (52.8 to 56.4) | 177 | 26.6 (20.6 to 33.6) | 480 | 49.2 (44.7 to 53.6) | 25 | 40.0 (22.7 to 60.2) | 41 | 29.3 (17.3 to 45.0) | 300 | 25.0 (20.4 to 30.2) | 90 | 30.0 (21.4 to 40.3) |

| 2010 | 58 626 | 51.9 (51.5 to 52.3) | 3855 | 51.0 (49.4 to 52.6) | 2894 | 54.2 (52.4 to 56.0) | 195 | 29.2 (23.3 to 36.0) | 500 | 50.6 (46.2 to 55.0) | 38 | 42.1 (27.4 to 58.3) | 38 | 26.3 (14.6 to 42.6) | 254 | 31.1 (25.7 to 37.1) | 89 | 34.8 (25.6 to 45.3) |

| 2011 | 60 259 | 52.7 (52.3 to 53.1) | 3953 | 50.3 (48.7 to 51.8) | 2977 | 53.2 (51.4 to 55.0) | 205 | 25.4 (19.9 to 31.8) | 468 | 52.1 (47.6 to 56.6) | 33 | 54.5 (37.4 to 70.7) | 33 | 45.5 (29.3 to 62.6) | 299 | 32. 1 (27.0 to 37.6) | 89 | 31.5 (22.6 to 41.9) |

| 2012 | 61 512 | 54.6 (54.2 to 55.0) | 4104 | 54.4 (52.9 to 56.0) | 3078 | 57.9 (56.2 to 59.7) | 222 | 24.8 (19.5 to 30.9) | 510 | 55.1 (50.7 to 59.4) | 34 | 50.0 (33.5 to 66.5) | 25 | 28.0 (13.7 to 48.7) | 315 | 36.8 (31.7 to 42.3) | 69 | 39.1 (28.3 to 51.1) |

| 2013 | 60 995 | 58.4 (58.0 to 58.8) | 4098 | 56.8 (55.3 to 58.3) | 3054 | 60.4 (58.7 to 62.2) | 244 | 32.8 (27.2 to 38.9) | 508 | 54.9 (50.6 to 59.2) | 29 | 48.3 (30.7 to 66.3) | 20 | 40.0 (21.0 to 62.6) | 290 | 39.3 (33.8 to 45.1) | 88 | 35.2 (25.9 to 45.8) |

| 2014 | 58 943 | 62.7 (62.4 to 63.1) | 3956 | 60.4 (58.8 to 61.9) | 2959 | 64.5 (62.7 to 66.2) | 265 | 35.8 (30.3 to 41.8) | 486 | 56.4 (51.9 to 60.7) | 23 | 69.6 (47.9 to 85.0) | 16 | 50.0 (26.6 to 73.4) | 252 | 45.6 (39.6 to 51.8) | 91 | 33.0 (24.1 to 43.3) |

| 2015 | 50 677 | 67.7 (67.2 to 68.1) | 3226 | 67.2 (65.6 to 68.8) | 2415 | 71.7 (69.9 to 73.5) | 215 | 38.1 (31.9 to 44.8) | 394 | 63.2 (58.3 to 67.8) | 18 | 83.3 (58.2 to 94.7) | 11 | 54.5 (25.6 to 80.7) | 208 | 54.3 (47.5 to 61.0) | 68 | 44.1 (32.8 to 56.1) |

Peptic ulcer, oesophageal varices. N = denominator.

Appendix 5. Type of anticoagulant prescribed to eligible patients with atrial fibrillation with and without contraindications to anticoagulants, 2004–2015

| CHADS2 ≥1 | Prescribed anticoagulant | Vitamin K antagonists | NOACs | Multiple | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Warfarin | Parenteral | Other | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Year | Contraindications | n | n | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| 2004 | With | 2795 | 1120 | 1113 (99.4) | 0 | 7 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Without | 41 242 | 16 202 | 16 072 (99.2) | 14 (0.1) | 115 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2005 | With | 3115 | 1297 | 1284 (99.0) | 5 (0.4) | 7 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Without | 46 807 | 19 051 | 18 906 (99.2) | 23 (0.1) | 119 (0.6) | 0 | 3 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2006 | With | 3331 | 1436 | 1418 (98.7) | 6 (0.4) | 12 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Without | 51 331 | 21 632 | 21 466 (99.2) | 41 (0.2) | 123 (0.6) | 0 | 2 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2007 | With | 3340 | 1559 | 1541 (98.8) | 8 (0.5) | 10 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Without | 54 348 | 24 416 | 24 235 (99.3) | 48 (0.2) | 130 (0.5) | 0 | 3 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2008 | With | 3455 | 1696 | 1673 (98.6) | 9 (0.5) | 12 (0.7) | 0 | 2 (0.1) |

| Without | 57 467 | 26 913 | 26 695 (99.2) | 72 (0.3) | 139 (0.5) | 0 | 7 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2009 | With | 3815 | 1919 | 1894 (98.7) | 11 (0.6) | 14 (0.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Without | 61 504 | 29 424 | 29 165 (99.1) | 101 (0.3) | 152 (0.5) | 0 | 6 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2010 | With | 3855 | 1967 | 1938 (98.5) | 17 (0.9) | 11 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.1) |

| Without | 62 481 | 30 415 | 30 127 (99.1) | 122 (0.4) | 151 (0.5) | 4 (0.0) | 11 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2011 | With | 3953 | 1988 | 1947 (97.9) | 24 (1.2) | 12 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) |

| Without | 64 212 | 31 745 | 31 434 (99.0) | 138 (0.4) | 154 (0.5) | 5 (0.0) | 14 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2012 | With | 4104 | 2234 | 2174 (97.3) | 26 (1.2) | 12 (0.5) | 17 (0.8) | 5 (0.2) |

| Without | 65 616 | 33 578 | 33 113 (98.6) | 195 (0.6) | 148 (0.4) | 102 (0.3) | 20 (0.1) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2013 | With | 4098 | 2327 | 2192 (94.2) | 28 (1.2) | 10 (0.4) | 94 (4.0) | 3 (0.1) |

| Without | 65 093 | 35 640 | 34 252 (96.1) | 190 (0.5) | 137 (0.4) | 1034 (2.9) | 27 (0.1) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2014 | With | 3956 | 2388 | 2113 (88.5) | 39 (1.6) | 6 (0.3) | 227 (9.5) | 3 (0.1) |

| Without | 62 899 | 36 984 | 33 579 (90.8) | 211 (0.6) | 127 (0.3) | 3037 (8.2) | 30 (0.1) | |

|

| ||||||||

| 2015 | With | 3226 | 2168 | 1719 (79.3) | 29 (1.3) | 6 (0.3) | 411 (19.0) | 3 (0.1) |

| Without | 53 903 | 34 286 | 28 018 (81.7) | 185 (0.5) | 84 (0.2) | 5959 (17.4) | 40 (0.1) | |

NOACs = novel oral anticoagulants.

Funding

Nicola Adderley and Tom Marshall are funded by the NIHR CLAHRC West Midlands initiative. This article presents independent research and the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Ethical approval

Research carried out using The Health Improvement Network data was approved by the NHS South-East Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) in 2003,38 subject to independent scientific approval. Approval for this analysis was obtained on 2 April 2015 (SRC reference number 15THIN021).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions. Atrial fibrillation: national clinical guideline for management in primary and secondary care. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22(8):983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324(7329):71–86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aguilar MI, Hart R. Oral anticoagulants for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD001927. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001927.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguilar MI, Hart R, Pearce LA. Oral anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;3:CD006186. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006186.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on oral anticoagulation: third edition. Br J Haematol. 1998;101(2):374–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Atrial fibrillation: the management of atrial fibrillation. CG36. London: NICE; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Atrial fibrillation: management. CG180. London: NICE; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180 (accessed 14 Jun 2017) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holt TA, Hunter TD, Gunnarsson C, et al. Risk of stroke and oral anticoagulant use in atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract. 2012. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp12X656856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Cowan C, Healicon R, Robson I, et al. The use of anticoagulants in the management of atrial fibrillation among general practices in England. Heart. 2013;99(16):1166–1172. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scowcroft ACE, Cowie MR. Atrial fibrillation: improvement in identification and stroke preventive therapy — data from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink, 2000–2012. Int J Cardiol. 2014;171(2):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meinertz T, Kirch W, Rosin L, et al. Management of atrial fibrillation by primary care physicians in Germany: baseline results of the ATRIUM registry. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100(10):897–905. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0320-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meiltz A, Zimmermann M, Urban P, Bloch A, on behalf of the Association of Cardiologists of the Canton of Geneva. Atrial fibrillation management by practice cardiologists: a prospective survey on the adherence to guidelines in the real world. Europace. 2008;10(6):674–680. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogilvie IM, Newton N, Welner SA, et al. Underuse of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahri O, Roca F, Lechani T, et al. Underuse of oral anticoagulation for individuals with atrial fibrillation in a nursing home setting in France: comparisons of resident characteristics and physician attitude. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):71–76. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johansson C, Hägg L, Johansson L, Jansson JH. Characterization of patients with atrial fibrillation not treated with oral anticoagulants. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32(4):226–231. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2014.984952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baczek VL, Chen WT, Kluger J, Coleman CI. Predictors of warfarin use in atrial fibrillation in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenman MB, Baker L, Jing Y, et al. Why is warfarin underused for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation? A detailed review of electronic medical records. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(9):1407–1414. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.708653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenman MB, Simon TA, Teal E, et al. Perceived or actual barriers to warfarin use in atrial fibrillation based on electronic medical records. Am J Ther. 2012;19(5):330–337. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182546840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinberg BA, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, et al. Contraindications to anticoagulation therapy and eligibility for novel anticoagulants in older patients with atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;33(4):177–183. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arts DL, Visscher S, Opstelten W, et al. Frequency and risk factors for under- and over-treatment in stroke prevention for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation in general practice. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. MHRA public assessment report. Warfarin: changes to product safety information. London: MHRA; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Anticoagulation — oral. Scenario: Warfarin. London: NICE; 2015. http://cks.nice.org.uk/anticoagulation-oral#!scenario:3 (accessed 6 Jun 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 27.IMS Health Statistics. http://www.epic-uk.org/our-data/statistics.shtml (accessed 6 Jun 2017)

- 28.Maguire A, Blak BT, Thompson M. The importance of defining periods of complete mortality reporting for research using automated data from primary care. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(1):76–83. doi: 10.1002/pds.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, et al. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA. 2001;285(22):2864–2870. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, et al. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137(2):263–272. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loo B, Parnell C, Brook G, et al. Atrial fibrillation in a primary care population: how close to NICE guidelines are we? Clin Med. 2009;9(3):219–223. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.9-3-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaist D, Wallander MA, Gonzalez-Perez A, Garcia-Rodriguez LA. Incidence of hemorrhagic stroke in the general population: validation of data from The Health Improvement Network. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(2):176–182. doi: 10.1002/pds.3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gale NK, Greenfield S, Gill P, et al. Patient and general practitioner attitudes to taking medication to prevent cardiovascular disease after receiving detailed information on risks and benefits of treatment: a qualitative study. BMC Family Practice. 2011;12(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Public Health England. Atrial fibrillation prevalence estimates in England: application of recent population estimates of AF in Sweden. London: PHE; 2015. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20170302112650/http://www.yhpho.org.uk//resource/view.aspx?RID=207902 (accessed 8 Jun 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Health and Social Care Information Centre. Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) — 2014–15. QOF 2014–15: prevalence, achievements and exceptions at region and nation level. Atrial fibrillation. Leeds: HSCIC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witt DM, Clark NP, Martinez K, et al. Risk of thromboembolism, recurrent hemorrhage, and death after warfarin therapy interruption for intracranial hemorrhage. Thromb Res. 2015;136(5):1040–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nielsen PB, Larsen TB, Skjøth F, et al. Restarting anticoagulant treatment after intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation and the impact on recurrent stroke, mortality, and bleeding: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2015;132(6):517–525. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.IMS Health Ethics. http://www.epic-uk.org/our-data/ethics.shtml (accessed 6 Jun 2017)