Abstract

Background

The 2014 guidelines on cardiovascular risk assessment and lipid modification from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend statin therapy for adults with prevalent cardiovascular disease (CVD), and for adults with a 10-year CVD risk of ≥10%, estimated using the QRISK2 algorithm.

Aim

To determine risk factor levels required to exceed the risk threshold for statin therapy, and to estimate the number of adults in England who would require statin therapy under the guidelines.

Design and setting

Cross-sectional study using a sample representative of the English population aged 30–84 years.

Method

To estimate 10-year CVD risk different combinations of risk factor levels were entered into the QRISK2 algorithm. The NICE guidelines were applied to the sample using data from the Health Survey for England 2011.

Results

Even with optimal risk factor levels, males of different ethnicities would exceed the 10% risk threshold between the ages of 60 and 70 years, and females would exceed the threshold between 65 and 75 years. Under the NICE guidelines, 11.8 million males and females (37% of the adults aged 30–84 years) would require statin therapy, most of them (9.8 million) for primary prevention. When analysed by age, 95% of males and 66% of females without CVD in ages 60–74 years, including all males and females in ages 75–84 years, would require statin therapy.

Conclusion

Under the 2014 NICE guidelines, 11.8 million (37%) adults in England aged 30–84 years, including almost all males >60 years and all females >75 years, require statin therapy.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, general practice, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, prevention, risk, statins

INTRODUCTION

In 2014, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) released updated guidelines for cardiovascular risk assessment and lipid-lowering medication.1 The new guidelines expanded the eligible population for statin therapy to adults without a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) with a ≥10% 10-year CVD risk, whereas the 2008 guidelines recommended treatment only for those at ≥20% risk.2 In addition, NICE now recommends the QRISK2 algorithm to estimate CVD risk. Previously, no specific risk algorithm was endorsed.3

Although they have been subject to much debate,4–7 the 2014 NICE guidelines and their implications for the general population have scarcely been investigated. In this paper, the authors first sought to examine the QRISK2 risk algorithm to determine risk factor levels required to exceed the 10% risk threshold. They then used data from the Health Survey for England (HSE) 20118 to estimate the number, and summarise the risk factor profile, of adults who will be eligible for statin therapy under the new guidelines.

METHOD

Examination of QRISK2

The authors estimated the 10-year CVD risk using QRISK2, updated in 2015,9 for males and females between 30 and 84 years of age in 5-year increments, using different combinations of the 15 risk factors included in the algorithm.9,10

First, the authors assessed the impact of individual risk factors on the estimated 10-year risk. They varied the level of each risk factor separately across the entire range of values permitted by QRISK2, while holding other risk factors constant at their median or most commonly observed levels in HSE 2011. Risk factors that were not available in the survey were set to ‘no’ (Appendix 1). The authors conducted the analysis for systolic blood pressure with and without treatment for hypertension. The authors also estimated the 10-year CVD risk for profiles with all risk factor levels set to the median or most common values in the HSE sample, by ethnicity and sex. Next, the authors estimated the 10-year CVD risk using QRISK2 for a set of risk profiles with different levels of a subset of risk factors that are deemed more modifiable: body mass index (BMI), total-to-high-density-lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol ratio, systolic blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and smoking status. They used risk factor levels considered as optimal (a 1), and then added one elevated risk factor at a time, starting from the most prevalent in the HSE sample. The authors performed these analyses for white males and females, and the remaining risk factors were set to the most common values in the HSE sample as described above. For the profile with optimal risk factor levels, the authors also performed the analyses for each ethnicity.

How this fits in

The 2014 guidelines on cardiovascular risk assessment and lipid modification from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends statin therapy to patients with existing cardiovascular disease, and to patients without cardiovascular disease who have a 10-year risk of disease at ≥10%, as predicted by the QRISK2 algorithm. This study confirmed that age was an important driver of risk in the QRISK2 algorithm, and that from the age of 60–75 years, depending on sex and ethnicity, the risk threshold for primary prevention was exceeded in all adults, including those with no increased risk factors. Under the guidelines, 11.8 million (37%) adults in England aged 30–84 years, including almost all males >60 years and all females >75 years, would be eligible for statin therapy.

Application of the 2014 NICE guidelines in the HSE

The authors used the subsample of HSE 2011 participants who had provided a blood sample,8 because it included questions about lifetime history of CVD, whereas other years of the same survey allowed the participants to list their current longstanding illnesses that may have led to under-reporting of prevalent CVD. Of the 3564 participants aged 30–84 years in the subsample, the authors excluded 592 participants who had missing data on any of the risk factors included in the application of the QRISK2 algorithm (age, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, type 2 diabetes, BMI, systolic blood pressure, blood-pressure-lowering medication, and total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio). The final study population included 2972 HSE participants. The authors set Townsend deprivation score to 0 and the remaining predictors in the QRISK2 equation to ‘no’ for all participants, because information about the risk factors was not available in the HSE. For the same reason, the authors considered all participants with diabetes to have type 2 diabetes, and in the analyses did not consider the recommendations to offer statins to patients with chronic kidney disease, and to patients with type 1 diabetes aged ≥40 years.

Statistical analysis

The authors calculated 10-year CVD risk for each of the HSE participants using QRISK2. They then used sample weights to determine the proportion of the English population for whom statin therapy is recommended under the 2014 NICE guidelines. This proportion was multiplied by a population of 31.9 million English adults aged 30–84 years, and the number of adults who would require statin therapy was estimated. For those without prevalent CVD, the authors conducted these analyses by sex and age group (30–44 years, 45–59 years, 60–74 years, and 75–84 years). Finally, the authors used a logistic regression model to compare the characteristics of adults without CVD who were already on statin treatment with those of the adults who were eligible but not receiving statins. Analyses were made using Stata 12.

Table 1.

Example risk factor profiles used to estimate 10-year cardiovascular disease risk with QRISK2a

| Optimal | High BMI | + High total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio | + Treated hypertension | + Diabetes | + Moderate smoking | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.5 | 30.1 | 30.1 | 30.1 | 30.1 | 30.1 |

| Total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.2 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 110 | 110 | 110 | 135 | 135 | 135 |

| Treated hypertension | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Diabetes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Smoking status | Never | Never | Never | Never | Never | Moderate smoker |

Optimal BMI was defined according to an analysis of cohort studies assessing BMI and risk of cardiovascular disease worldwide.11 Optimal total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio was defined by the cut-off recommended by the NHS.12 Optimal systolic blood pressure was defined by the American Heart Association’s Prevention Guidelines panel.13 High BMI was set to the average level in adults aged 30–84 years with BMI ≥25 kg/m2 in the Health Survey for England 2011. High total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio was set to the average level among adults with a ratio of ≥4 and who were not receiving statins. Treated systolic blood pressure was set to the average level among adults who received blood pressure medication. For all risk factor profiles, ethnicity was set to ‘white or not stated’, Townsend deprivation score was set to 0, and remaining risk factors were set to ‘no’ (type 1 diabetes, family history of coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and rheumatoid arthritis). BP = blood pressure. BMI = body mass index. CVD = cardiovascular disease. HDL = high density lipoprotein.

RESULTS

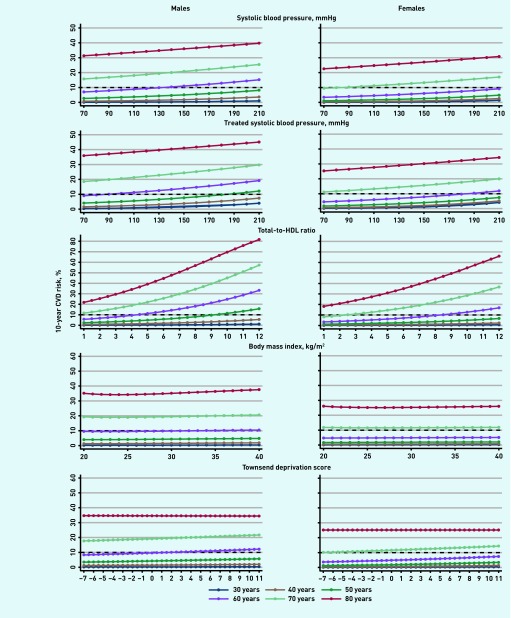

Figure 1 shows the 10-year CVD risk estimated when varying the level of each risk factor separately across the entire range of values permitted by QRISK2, while holding other risk factors constant at median values. BMI and Townsend score had modest effects on CVD risk compared with total-to-HDL ratio and treated systolic blood pressure in both males and females. For example, increasing BMI from 20 to 40 kg/m2 (the full range in QRISK2) in a 60-year-old male with median risk factor levels increased the predicted risk from 9.5 to 10.4%. In contrast, the risk estimated using the full range of treated systolic blood pressure (70 to 210 mmHg) in the same male increased the risk from 9.0 to 19.2% (Figure 1). Of the categorical risk factors, type 1 diabetes had the largest impact on estimated risk in both males and females (further data available from the authors upon request). It increased the risk from 9.6 to 24.4% in a 60-year-old white male with median risk factor levels, and from 4.8 to 16.2% for a female with the same risk factor profile.

Figure 1.

The 10-year CVD risk estimated with QRISK2, and by varying levels of single risk factors in hypothetical white males and females at selected ages.a

aOther risk factors in the risk prediction equation were either held constant at median levels in HSE 2011 (BMI, systolic BP, total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio) or assumed to be non-existent (type 1 and 2 diabetes, smoking, treated hypertension, family history of coronary heart disease in first-degree relative <60 years, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, rheumatoid arthritis, and Townsend score). BMI = body mass index. CVD = cardiovascular disease. HDL = high-density lipoprotein. HSE = Health Survey for England.

The association between risk factors and CVD risk was modified by age. Negative age interactions were reflected in weaker associations between risk factors and CVD risk in higher ages. For example, in a 40-year-old white male with median risk factor levels, type 2 diabetes increased CVD risk from 1.4 to 3.9% (relative risk [RR] 2.8) whereas the corresponding risk increase for an 80-year-old male with the same risk factor profile was 35 to 46% (RR 1.3) (further data available from the authors upon request). RRs for the lowest versus the highest Townsend deprivation score (−7 versus 11) for the same male were 1.7 at the age of 40 years, and 1.0 at the age of 80 years (Figure 1).

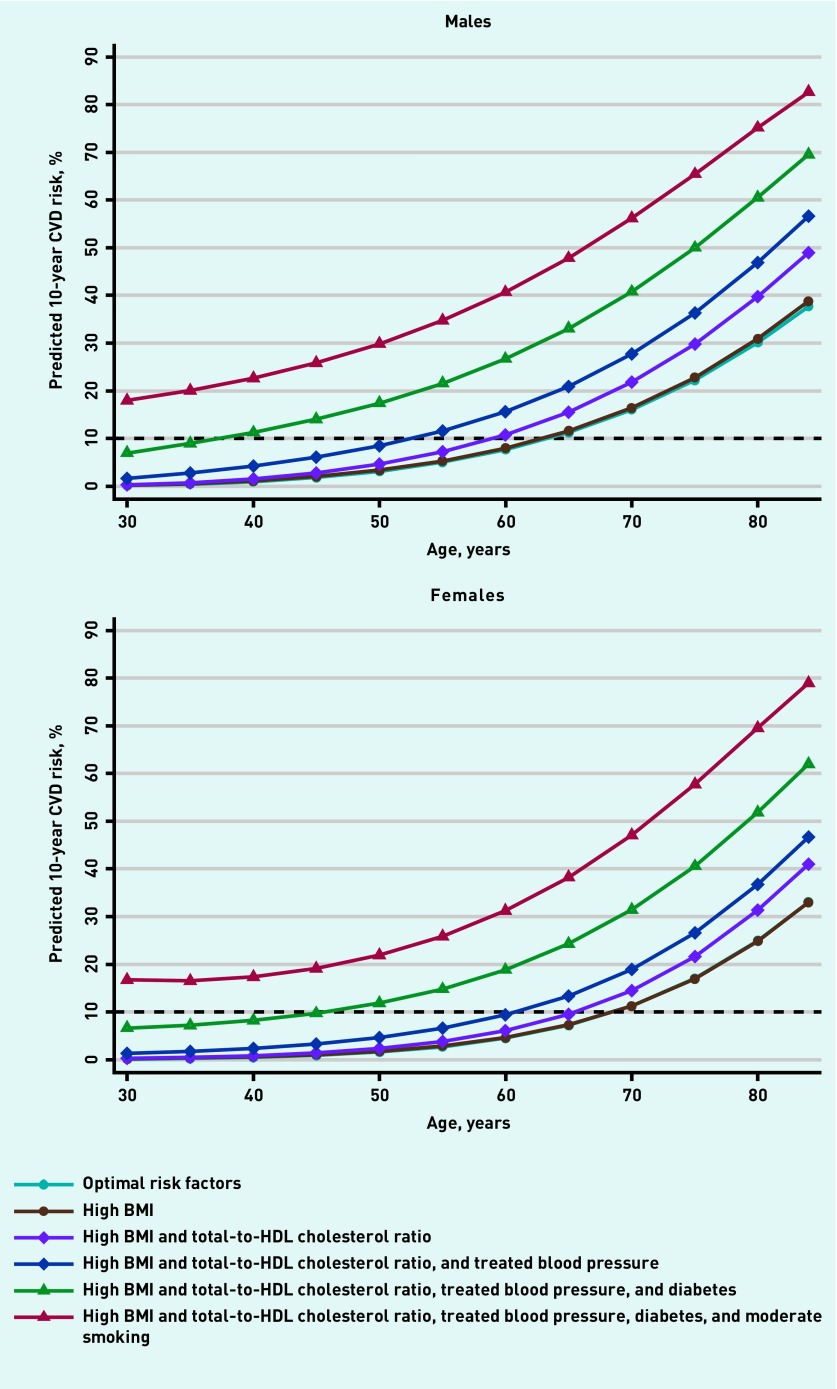

The 10-year CVD risk estimated with QRISK2 for white males and females with different risk factor profiles are shown in Figure 2. An obese white male with treated hypertension and a high total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio did not exceed the 10% risk threshold until the age of 55 years, whereas the threshold was exceeded at the age of 40 if he had type 2 diabetes, and at the age of 30 if he also was a moderate smoker. An obese white female with treated hypertension and a high total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio did not exceed the 10% risk threshold until the age of 65 years. But the risk threshold was exceeded at the age of 45 if she had type 2 diabetes, and at the age of 30 if she also was a moderate smoker

Figure 2.

The 10-year CVD risk estimated with QRISK2, by age for hypothetical white males and females with different combinations of risk factors as shown in Table 1.a,baOptimal/high BMI = 22.5/30.1 kg/m2. Optimal/high total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio = 4.0/5.2. Optimal systolic BP = 110 mmHg (untreated). Treated systolic BP = 135 mmHg. Optimal smoking status = never smoker. bAll other risk factors were assumed to be non-existent (type 1 diabetes, family history of coronary heart disease in first-degree relative <60 years, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, rheumatoid arthritis, and Townsend score). BMI = body mass index. CVD = cardiovascular disease. HDL = high-density lipoprotein.

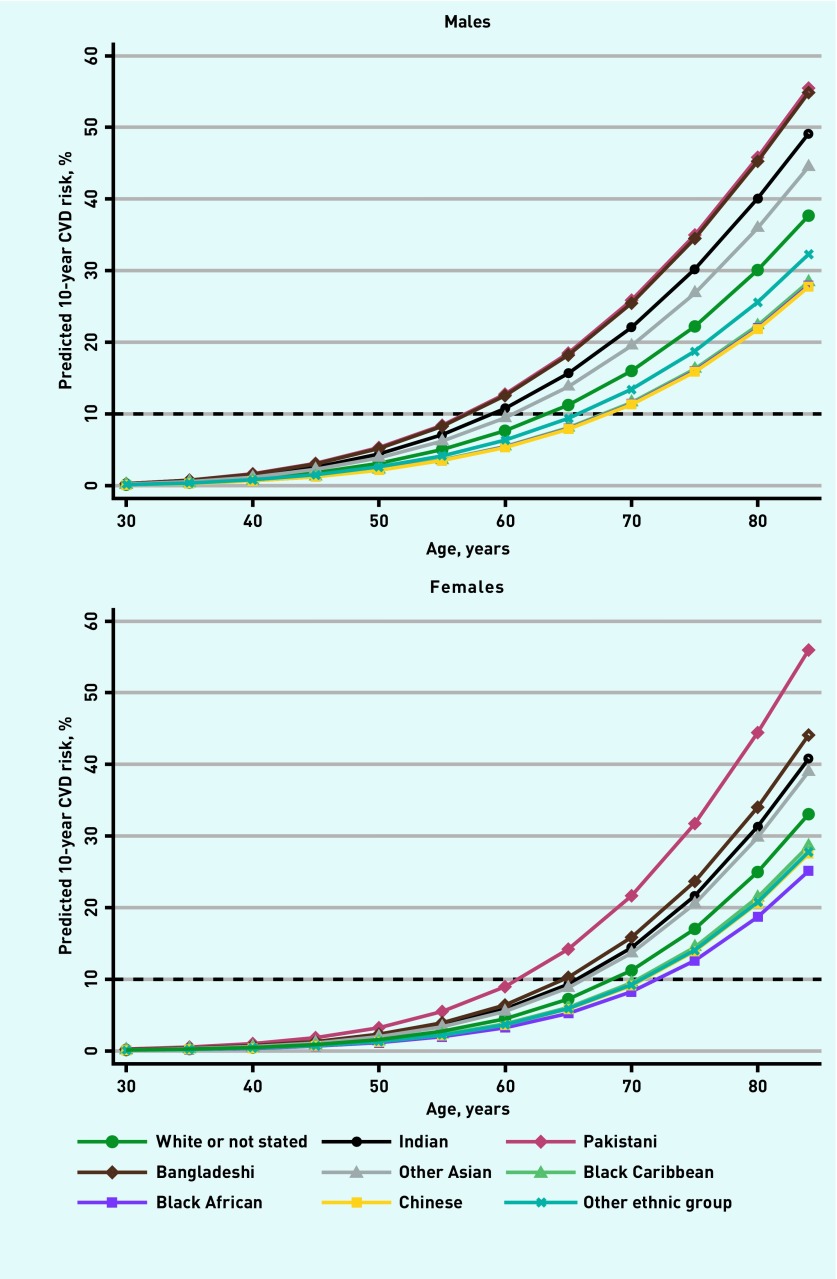

The 10% risk threshold was exceeded by males and females even if they had optimal risk factor levels (Figure 3). A male with optimal risk factor levels would exceed the risk threshold at the age of 60 years if he was of Bangladeshi, Pakistani, or Indian origin, and at the age of 70 years regardless of his ethnicity. A female with optimal risk factor levels would exceed the risk threshold by the age of 65 years if she was of Pakistani or Bangladeshi origin, and between the ages of 65 and 75 years if she was of other ethnicities. The proportion of English adults in the HSE with optimal risk factor levels was 2%, and adults with median risk factor levels exceeded the threshold earlier, at ages 55 to shortly after 70 years, depending on sex and ethnicity (further data available from the authors upon request).

Figure 3.

The 10-year CVD risk estimated with QRISK2, by age and ethnicity, for hypothetical males and females with optimal risk factor levels.aaBMI = 22.5 kg/m2. Systolic BP = 110 mmHg. Total-to-HDL cholesterol ratio = 4, and never smoker and no diabetes. All other risk factors were assumed to be non-existent (family history of coronary heart disease in first-degree relative <60 years, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, rheumatoid arthritis, and Townsend score). CVD = cardiovascular disease.

In total, 11.8 million (out of 31.9 million; 37%) English adults aged 30–84 years required statin therapy under the 2014 NICE guidelines. Of the 9.8 million adults without CVD who would require statins (33% of the population without CVD), 3.5 million adults (12%) were already receiving statins and 6.3 million adults (21%) were eligible for treatment (Table 2). Of the 2.0 million adults with existing CVD, 380 000 (19%) were not receiving statins.

Table 2.

Cardiovascular risk profile of English adults aged 30–84 years without existing cardiovascular disease by their eligibility and treatment status under the 2014 guidelines, estimated using data from HSE 2011a

| Total population aged 30–84 years and free of CVD, N= 29 936 (100%) | Receiving statins for primary prevention, N= 3522 (12%) | Eligible but not receiving statin therapy for primary prevention, N= 6305 (21%) | Receiving statins versus being eligible but not treated,b,c ORs (95% CIs) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 15 420 (52) | 1437 (41) | 2704 (43) | 1.09 (0.79 to 1.50) |

|

| ||||

| Age, years | 50 (40–62) | 64 (55–72) | 67 (62–73) | 0.61 (0.52 to 0.73) |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White or not stated | 27 286 (91) | 3280 (93) | 6028 (96) | Ref |

| South Asian or other Asian | 1457 (5) | 173 (5) | 214 (3) | 0.82 (0.35 to 1.90) |

| Other | 1193 (4) | 70 (2) | 63 (1) | 1.53 (0.51 to 4.62) |

|

| ||||

| IMD, quintile | ||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 6827 (23) | 760 (22) | 1424 (23) | Ref |

| 2 | 6934 (23) | 827 (24) | 1479 (24) | 1.02 (0.68 to 1.53) |

| 3 | 6104 (20) | 735 (21) | 1370 (22) | 0.95 (0.64 to 1.41) |

| 4 | 5325 (18) | 637 (18) | 1171 (19) | 0.97 (0.62 to 1.53) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 4745 (16) | 564 (16) | 861 (14) | 0.93 (0.54 to 1.59) |

|

| ||||

| Completed higher education | 7866 (26) | 519 (15) | 1008 (16) | 0.97 (0.62 to 1.49) |

|

| ||||

| Urban resident | 22 896 (77) | 2580 (73) | 4579 (73) | 0.93 (0.65 to 1.32) |

|

| ||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.4 (4.7–6.1) | 4.5 (3.9–5.3) | 5.8 (5.2–6.5) | – |

|

| ||||

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | – |

|

| ||||

| Hypertension | 9234 (31) | 2365 (67) | 3632 (58) | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.94) |

|

| ||||

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 124.5 (115–136) | 131.5 (122.5–143) | 134.5 (123.5–146) | – |

|

| ||||

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 73.5 (67–81) | 73.5 (67–80) | 74 (67–83) | – |

|

| ||||

| Receiving BP medication | 4839 (16) | 1894 (54) | 2115 (34) | 3.30 (2.09 to 5.20) |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes | 2283 (8) | 1181 (34) | 831 (13) | 2.66 (1.76 to 4.02) |

|

| ||||

| Overweight, BMI ≥25–<30 kg/m2 | 12 536 (42) | 1351 (38) | 2905 (46) | 1.08 (0.72 to 1.61) |

|

| ||||

| Obesity, BMI ≥30 kg/m2 | 7920 (27) | 1661 (47) | 1955 (31) | 1.23 (0.78 to 1.94) |

|

| ||||

| Former smoker | 10 209 (34) | 1677 (48) | 2719 (43) | 1.07 (0.77 to 1.48) |

|

| ||||

| Current smoker | 5620 (19) | 445 (13) | 1212 (19) | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.77) |

|

| ||||

| 10-year CVD risk (QRISK2), %d | 4.3 (1.2–12.0) | 16.6 (10.2–25.1) | 18.4 (13.1–26.3) | – |

Numbers are shown in thousands and per cent of population for categorical variables, and median and interquartile range for continuous ones. Numbers do not correspond to the column total for IMD quintile and for ethnicity in those receiving statins because of rounding.

Odds ratios for receiving statins versus being eligible but not treated were estimated using a logistic regression model with the following independent variables: female sex, age (per 10 years), ethnicity (reference = white or not stated), Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile (reference = least deprived), completed higher education, urban resident, hypertension, receiving blood pressure medication, diabetes, weight status (reference = BMI <25 kg/m2), and smoking status (reference = never smoker).

P-value (Wald test): ethnicity = 0.65, Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles = 0.99, weight status = 0.62.

The QRISK2 algorithm only permits total-to-HDL cholesterol ratios of up to 12, and BMI values ranging from 20 to 40 kg/m2. Therefore, in the estimation of 10-year CVD risk using QRISK2, total-to-HDL cholesterol ratios of >12 were set to 12 in two participants (out of the total 2972 participants), BMI values of <20 kg/m2 were set to 20 kg/m2 in 78 participants, and BMI values of >40 kg/m2 were set to 40 kg/m2 in 78 participants. BMI = body mass index. BP = blood pressure. CVD = cardiovascular disease. HDL = high-density lipoprotein. HSE = Health Survey for England. IMD = Index of Multiple Deprivation. OR = odds ratio. Ref = reference.

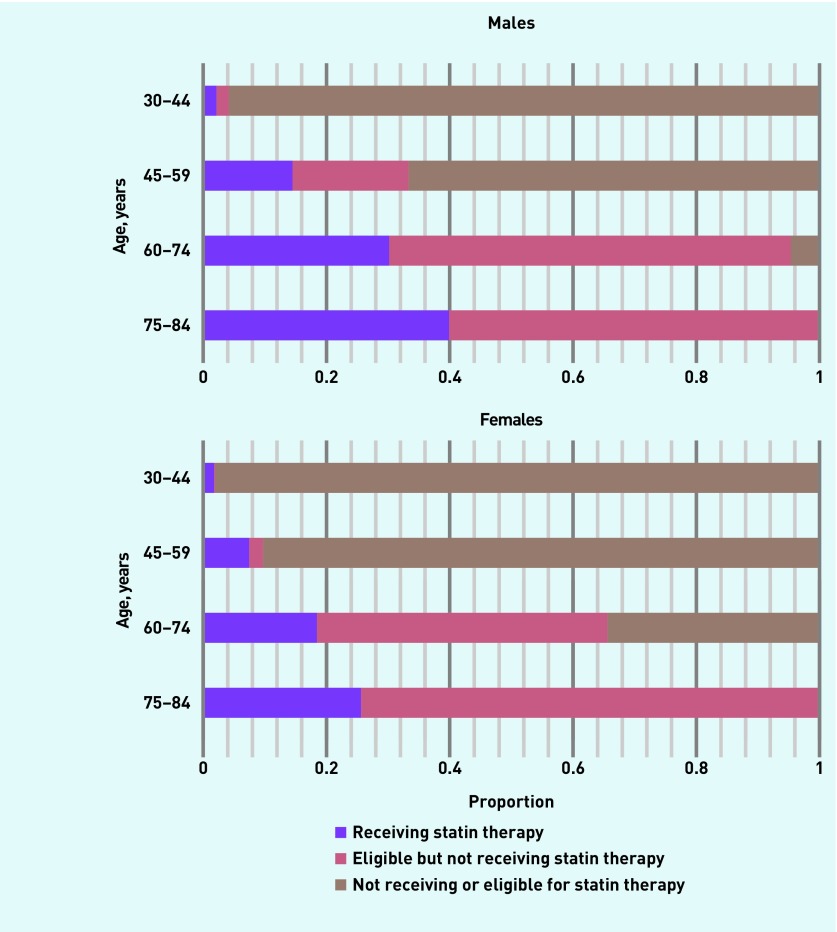

Most adults who were eligible or treated for primary prevention were in older age groups. Although only 4% of males aged 30–44 years and free of existing CVD required statin therapy, this proportion was 33% in ages 45–59 years, 95% in ages 60–74 years, and 100% in ages 75–84 years. The corresponding numbers for females were 2% in ages 30–44 years, 10% in ages 45–59 years, 66% in ages 60–74 years, and 100% in ages 75–84 years (Figure 4). In the logistic regression model, independent predictors of receiving statins compared with being eligible but untreated were younger age, diabetes and blood pressure treatment, no hypertension, and no current smoking (Table 2). Weight status (P = 0.62), ethnicity (P = 0.65), and multiple deprivation quintile (P = 0.99) were not associated with receiving statins.

Figure 4.

Proportion of the adult English population without existing CVD who are receiving statin therapy, or are eligible but not receiving statins, under the 2014 NICE guidelines, by age and sex. CVD = cardiovascular disease. NICE = National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

DISCUSSION

Summary

The authors estimated that, under the updated NICE guidelines, 11.8 million English males and females would be receiving or eligible for statin therapy, representing 37% of the adults in ages 30–84 years. The majority of these adults (9.8 million) would be treated or eligible for primary prevention. Under the new guidelines, 95% of males and two-thirds of females without existing CVD in ages 60–74 years, and all males and females in ages 75–84 years, would require statin therapy.

The QRISK2 algorithm gives a large weight to age as a predictor of CVD risk.10 Even with optimal risk factor levels, males of different ethnicities would exceed the 10% risk threshold between the ages of 60 and 70 years, and females would exceed the threshold between 65 and 75 years. The proportion of English adults with optimal risk factors was only 2%, and most adults exceed the treatment threshold at an earlier age.

Strengths and limitations

The authors used a nationally representative sample of English adults and visualised characteristics of the QRISK2 algorithm. The study has limitations. First, the authors had to set a number of risk factors in the QRISK2 algorithm to ‘no’ (type 1 diabetes, family history of coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and rheumatoid arthritis), because data were not available, and they may therefore have underestimated the risk in the population and the number of adults eligible for statin therapy under the 2014 NICE guidelines. Second, the authors only used one HSE sample from 2011, because it was the only survey that included questions on lifetime CVD history. Third, the authors could not assess the eligibility of the adults who were already on treatment for primary prevention, because they could not determine why statin therapy had been initiated. Finally, in the examination of the QRISK2 algorithm, the authors focused on a particular set of risk factor combinations, although other risk factor combinations may be more commonly observed in the population of England.

Comparison with existing literature

The importance of age in the QRISK2 algorithm has already been reported.10 This means that all adults, including those with no increased risk factors, at some point in their lives are likely to be eligible for statin therapy. There is limited evidence from clinical trials on statin efficacy among older people,14 and uncertainties remain regarding adverse effects.15 As is recommended in the NICE guidelines, as well as in other national and international guidelines,16 a physician–patient discussion should precede decisions on statin therapy, in particular for patients whose eligibility for treatment is based solely on their age.

Conversely, the QRISK2 algorithm does not assign a risk above the treatment threshold for many males and females in younger age groups, even if they have high levels of multiple risk factors. Younger patients with several elevated risk factors may therefore benefit from an assessment of their long-term CVD risk (for example, lifetime risk17 or ‘heart age’18,19).

Although heatedly debated,4–7 the 2014 NICE guidelines and their implications for the general population have not been subject to much investigation. The costing report that accompanied the 2014 NICE guidelines estimated that 25% of the adult population of England free of existing CVD would be eligible for statins under the 2014 NICE guidelines.20 The authors estimated that 33% of the adults without CVD would require statins, including the 12% who were already receiving treatment for primary prevention.

Assuming that the 10-year CVD risk estimated with QRISK2 accurately reflects future CVD risk, the authors estimated that there would be 1.16 million cardiovascular events over the next 10 years among the 6.3 million adults without existing CVD who were currently untreated and eligible for statin therapy under the 2014 NICE guidelines. If a 25% risk reduction from statin use, corresponding to a 1 mmol reduction in low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, is assumed for primary prevention, as reported in a meta-analysis of clinical trials,21 and adherence to treatment similar to that in the trials, full implementation of the 2014 NICE guidelines would prevent 290 000 of these events.

It is, however, unlikely that all eligible adults will receive statins. The 2014 NICE guidelines recommend an informed risk–benefit discussion between the physician and the patient. A treatment recommendation will therefore not necessarily lead to treatment initiation. Moreover, the effects of the expanded recommendations for statin therapy may be limited by an incomplete implementation of the guidelines. In fact, a report using data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) during the years 2007–2011 showed that 69% of the patients who were eligible for statin therapy under the previous 2008 guidelines were not receiving statins.22 Compared with those already under statin therapy, the authors’ analyses also showed that the adults who were untreated and eligible under the 2014 NICE guidelines were less likely to be diabetic and receiving blood pressure treatment, and therefore they could be harder to identify and treat, as their contact with the healthcare system may be less frequent. In addition, adherence to statin therapy has been reported to be low in everyday clinical practice. A recent study using data from CPRD showed that 47% of the patients prescribed statins as primary prevention had at least 90 days of discontinued treatment during a median follow-up time of 137 weeks.23

Implications for practice

Even if providing statin therapy to a large part of the population is deemed to be cost-effective,1,20,24 it will still require resources to screen, treat, and monitor the patients who are put on treatment. The approximately 33 000 GPs (full-time equivalents, excluding registrars and retainers) in England25 would need to treat close to 200 patients each to provide statin therapy to those who are untreated but eligible for treatment under the NICE guidelines. Implementation of the NICE guidelines should be considered in the context of opportunity costs for primary care and its available resources, in particular given the high and increasing workload facing GPs in England.26

Appendix 1. Median levels of continuous risk factors and most commonly observed levels of categorical risk factors in adults aged 30–84 years in Health Survey for England 2011

| Males | Females | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 | 26.7 |

| Total-to-HDL cholesterol ratioa | 4.1 | 3.4 |

| Systolic blood pressure,b mmHg | 126.5 | 118 |

| Ethnicity | White or not stated | White or not stated |

| Smoking status | Never | Never |

| Type 2 diabetes | No | No |

| Treated hypertension | No | No |

| Townsend deprivation scorec | 0 | 0 |

| Type 1 diabetesd | No | No |

| Family history of coronary heart disease in first-degree relative <60 yearsd | No | No |

| Chronic kidney diseased | No | No |

| Atrial fibrillationd | No | No |

| Rheumatoid arthritisd | No | No |

In adults not receiving statin therapy.

In adults not receiving blood pressure medication.

Not available in HSE 2011 and 0 reflects the median level in the population.

Not available in HSE 2011 and the most common level was assumed to be ‘no’. BMI = body mass index. HDL = high-density lipoprotein.

Funding

Peter Ueda was supported by the Swedish Society of Medicine and Gålöstiftelsen. Thomas Wai-Chun Lung received salary support as the HCF Research Foundation Postdoctoral Research Fellow. The Health Survey for England was funded by the Department of Health until 2004 and the Health and Social Care Information Centre from 2005. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. CG181. London: NICE; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181 (accessed 6 Jul 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. CG67. London: NICE; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayor S. Doctors no longer have to use Framingham equation to assess heart disease risk, NICE says. BMJ. 2010;340:c1774. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldacre B, Smeeth L. Mass treatment with statins. BMJ. 2014;349:g4745. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majeed A. Statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 2014;348:g3491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall T. Statins: let us identify and treat those at high CV risk first. Prescriber. 2014;25(17):7–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Editorial Statins for millions more? Lancet. 2014;383(9918):669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NatCen Social Research, University College London Department of Epidemiology and Public Health. Health survey for England, 2011. 2013. [Data collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 7260. . [DOI]

- 9. QRISK2-2015. http://www.qrisk.org/ (accessed 28 Jun 2017)

- 10.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1475–1482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39609.449676.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wormser D, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Separate and combined associations of body mass index and abdominal adiposity with cardiovascular disease: collaborative analysis of 58 prospective studies. Lancet. 2011;377(9771):1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60105-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS Choices Your NHS Health Check results and action plan. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/nhs-health-check/pages/understanding-your-nhs-health-check-results.aspx#bp (accessed 28 Jun 2017)

- 13.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedro-Botet J, Climent E, Chillarón JJ, et al. Statins for primary cardiovascular prevention in the elderly. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2015;12(4):431–438. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai CS, Martin SS, Blumenthal RS. Non-cardiovascular effects associated with statins. BMJ. 2014;349:g3743. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jansen J, McKinn S, Bonner C, et al. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines recommendations about primary cardiovascular disease prevention for older adults. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:104. doi: 10.1186/s12875-015-0310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Robson J, Brindle P. Derivation, validation, and evaluation of a new QRISK model to estimate lifetime risk of cardiovascular disease: cohort study using QResearch database. BMJ. 2010;341:c6624. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson R, Kerr A, Wells S, et al. ‘Should we reconsider the role of age in treatment allocation for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease?’ No, but we can improve risk communication metrics. Eur Heart J. 2016 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.JBS 3 Board. Joint British Societies’ consensus recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2014;100:ii1–ii67. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. National costing report: lipid modification. London: NICE; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181/resources/lipid-modification-update-costing-report-pdf-243777565 (accessed 28 Jun 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists (CTT) Collaborators. Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):581–590. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Staa T-P, Smeeth L, Ng ES-W, et al. The efficiency of cardiovascular risk assessment: do the right patients get statin treatment? Heart. 2013;99(21):1597–1602. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Brindle P, Hippisley-Cox J. Discontinuation and restarting in patients on statin treatment: prospective open cohort study using a primary care database. BMJ. 2016;353(9841):i3305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandya A, Sy S, Cho S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of 10-year risk thresholds for initiation of statin therapy for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2015;314(2):142–150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Workforce and Facilities Team — Health and Social Care Information Centre. General and Personal Medical Services England 2002–2013. HSCIC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hobbs FD, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, et al. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007–14. Lancet. 2016;387(10035):2323–2330. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]