Abstract

Background

A delayed or ‘just in case’ prescription has been identified as having potential to reduce antibiotic use in sore throat.

Aim

To determine the symptomatic outcome of acute sore throat in adults according to antibiotic prescription strategy in routine care.

Design and setting

A secondary analysis of the DESCARTE (Decision rule for the Symptoms and Complications of Acute Red Throat in Everyday practice) prospective cohort study comprising adults aged ≥16 years presenting with acute sore throat (≤2 weeks’ duration) managed with treatment as usual in primary care in the UK.

Method

A random sample of 2876 people from the full cohort were requested to complete a symptom diary. A brief clinical proforma was used to collect symptom severity and examination findings at presentation. Outcome details were collected by notes review and a detailed symptom diary. The primary outcome was poorer ‘global’ symptom control (defined as longer than the median duration or higher than median symptom severity). Analyses controlled for confounding by indication (propensity to prescribe antibiotics).

Results

A total of 1629/2876 (57%) of those requested returned a symptom diary, of whom 1512 had information on prescribing strategy. The proportion with poorer global symptom control was greater in those not prescribed antibiotics 398/587 (68%) compared with those prescribed immediate antibiotics 441/728 (61%) or delayed antibiotic prescription 116/197 59%); adjusted risk ratio (RR) (95% confidence intervals [CI]): immediate RR 0.87 (95% CI = 0.70 to 0.96), P = 0.006; delayed RR 0.88 (95% CI = 0.78 to 1.00), P = 0.042.

Conclusion

In the routine care of adults with sore throat, a delayed antibiotic strategy confers similar symptomatic benefits to immediate antibiotics compared with no antibiotics. If a decision is made to prescribe an antibiotic, a delayed antibiotic strategy is likely to yield similar symptomatic benefit to immediate antibiotics

Keywords: antibiotics, cohort studies, delayed prescribing, drug prescribing, sore throat, symptom control

INTRODUCTION

Acute sore throat is common in everyday practice in primary care and antibiotics are still frequently prescribed.1 The Cochrane Review of acute sore throat management2 included 27 trials and more than 12 000 cases of sore throat, and found that antibiotics reduced the duration of pain symptoms by an average of 1 day. Current UK guidelines recommend a delayed or no prescription strategy for acute sore throat.3 Despite the guidelines and systematic review evidence described, most patients presenting with acute sore throat are prescribed immediate antibiotics.1,4 An alternative strategy — using a delayed antibiotic prescription — has been shown to reduce antibiotic uptake without any effect on recovery or patient satisfaction,5 and to confer a similar protective effect against complications as an immediate prescription.6 However, the rationale of a delayed prescription has been called into question because it results in higher antibiotic uptake than a no prescription strategy, with a suggestion that a delayed strategy is inferior to immediate antibiotics for some sore throat symptoms.7

Observational studies provide useful evidence to complement experimental studies, given the concerns that randomised trial participants and their behaviour during trials (such as relating to adherence) may be atypical, and hence that estimates of effectiveness may not be applicable to patients consulting routinely.

In order to describe current practice and outcome related to prescribing strategy in adults, a large observational cohort that had been recruited to examine potential prediction of septic complications of acute sore throat was investigated. In a subset of participants completing a symptom diary, the symptomatic outcomes and illness duration in relation to prescribing strategy were analysed.

METHOD

Study design

This was a secondary analysis of the DESCARTE (Decision rule for the Symptoms and Complications of Acute Red Throat in Everyday practice) study, which as reported elsewhere was a large prospective cohort of patients presenting with acute sore throat in routine primary care in the UK. 6,8 A simple one-page paper and/or web-based case report form (CRF) was used to document clinical features at presentation. Smaller studies were nested in the cohort to develop and trial a clinical scoring method for bacterial infection. The nested studies were two consecutive diagnostic cohorts (n = 1107) where a clinical score to predict bacterial infection was developed, and a randomised trial (n = 1781) that compared the use of the clinical score and the targeted use of a rapid antigen detection test with delayed antibiotic prescribing.9 Participants in the trial were not included in this analysis because antibiotics were targeted according to trial criteria. Recruitment took place between 10 November 2006 and 1 June 2009, from 616 recruiting practices. Initial recruitment was among six local networks (based in Southampton, Bristol, Birmingham, Oxford, Cardiff, and Exeter) but was extended nationally during the last 18 months of recruitment.

How this fits in

Antimicrobial resistance is a major threat to public health. In the UK, 75% of antibiotics are prescribed in primary care, mainly for respiratory tract infections. Experimental studies suggest modest symptom benefit when antibiotics are prescribed for sore throat. In routine practice, antibiotics do confer modest symptomatic improvement on average and similar effects are seen with delayed and immediate prescribing. However, delayed prescribing results in reduced antibiotic uptake compared with immediate prescribing.

Patient inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were previously well patients aged ≥16 years with acute illness (≤14 days), presenting in primary care with sore throat as the main symptom, and with an abnormal examination of the pharynx (identical criteria to the authors’ previous studies).5 Exclusion criteria were severe mental health problems (such as cognitive impairment associated with being unable to consent or assess history) and known immune suppression. GPs recorded a detailed history and examination findings, and then treated the patient as usual. Antibiotic treatment was therefore determined by individual practitioners in accordance with their usual practice.

Baseline clinical proforma

A simple clinical sheet was used to document age, sex, current smoking status, prior duration of illness, and the presence and severity of baseline symptoms (sore throat, difficulty swallowing, fever during the illness, runny nose, cough, feeling unwell, diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain, headache, muscle ache, sleep disturbance, and earache). Symptoms were recorded using a 4-point Likert scale (none, a slight problem, a moderately bad problem, or a severe problem), and the presence of signs (pus, cervical nodes, temperature, fetor, palatal oedema, and difficulty speaking because of sore throat). No laboratory tests were specified.

Documentation of primary outcome

A request to complete a symptom diary was randomly allocated to a proportion of those recruited to the study to achieve a pre-specified target of 1800 diaries. Initial allocation was randomly allocated to one in 10 participants by including the diary in recruitment packs. The allocation ratio was altered part way through the study to one in two packs in most centres, on account of observed low return rates. Allocation was one in four recruitment packs in Southampton because of the inclusion of an alternative questionnaire. The diary was similar to that used in other studies.5,10

Patients completed the diary each night until symptoms resolved or for up to 14 nights. Each symptom was scored (from 0 = no problem to 6 = as bad as it could be): sore throat, difficulty swallowing, feeling unwell, fever, and sleep disturbance. Adverse symptomatic outcome was defined as being either above the median for symptom severity at day 2–4 or above the median duration of moderately bad symptoms, that is, either or both qualified for adverse symptomatic outcome.

Other outcomes

In order to allow comparison with other studies, symptom severity on day 2–4 and the duration of moderately bad symptoms (in days) were also assessed.5,10

Sample size

Sample size calculations calculated using nQuery for the main study were based on the prediction of complications — a rare outcome. For the proposed analysis of diary data, a sample of 1800 patients allowing for 20% loss to follow-up of diaries (900 of whom would not be expected to have antibiotics), would have power to detect variables with prevalence between 20% to 80%, with an odds ratio of 2 for adverse symptomatic outcome among the no antibiotic group.

Analysis

Duration of symptoms was analysed using Cox regression, linear regression was used for symptom severity, and a generalised linear model with a log link and binomial distribution was used for worsening of illness and adverse symptomatic outcome. Missing data on outcome were not imputed. Both the univariate statistics and the relationships after controlling for the severity of all baseline symptoms and clustering of patients by practice are reported.

The Centor score, used widely to target treatment at those at higher risk of streptococcal infection, was derived in an emergency room setting where a score of ≥3 predicted a 32% risk of positive culture.11 The FeverPAIN score, which comprises fever in the past 24 hours, purulence, rapid (within 3 days) attendance, inflamed tonsils, and no cough or cold symptoms, may also be used to predict the probability of streptococcal infection in community samples and has been shown to be highly predictive of time to symptom resolution and symptom severity.12 An interaction between Centor/FeverPAIN and antibiotic prescribing strategy was tested for, which was to determine if those more likely to have streptococcal infection had evidence of a differential response to antibiotics. The scores were used to dichotomise the sample into those more or less likely to have a streptococcal infection: for Centor a cut-off point of ≥3 was used and for FeverPAIN a cut-off point of 0–2 versus ≥3 was used. For FeverPAIN at the cut-off point of 0–2 the probability of a streptococcus swab positive result is 26%, while for those with a score of ≥3 it is 60%.12 For Centor the probability of a streptococcus swab positive result is 15% for those with a score of 2 and 32% for those with a score of 3 or above.11

Analyses were carried out in Stata (version 12.1). To control for potential confounding by indication, a propensity score based on predictors of antibiotic prescribing (none versus immediate and none versus delayed) was calculated using a chained equations multiple imputation model. Results are presented both for complete cases and for models with significant predictors of the propensity score imputed. Outcome measures were not imputed because it was not possible to distinguish between individuals who were missing data because they did not complete a diary when asked and those who were not asked to complete one.

Results

Descriptive data

In the full cohort study, 14 610 adult patients were recruited between 10 November 2006 and 1 June 2009 from 616 general medical practices. A total of 1629/2876 (57%) returned a symptom diary, of whom 1512 had information on prescribing strategy. The baseline characteristics of patients recruited and of those who maintained a symptom diary are shown in Appendix 1. Those given immediate antibiotics had more severe symptoms at baseline and were more likely to have a history of fever and severe inflammation or pus on tonsils.6 Those returning the diary were slightly older, and more likely to be female and a non-smoker, compared with the whole sample.

In those returning a diary, no antibiotics were prescribed for 587/1512 (39%), immediate antibiotics were prescribed for 728/1512 (48%), and delayed antibiotics were prescribed for 197/1512 (13%). These are similar to the proportions prescribed to the full cohort: 4805/12 677 (38%), 6088/12 677 (48%), and 1784/12 677 (14%), respectively. In those completing a diary, 115/197 58% of those given a delayed prescription reported using the prescription. Delayed prescribing was only reported by those recruited from approximately one half of participating practices 320/616 (52%).

Impact of prescribing strategies on symptom control

When controlling for propensity to prescribe antibiotics compared with no antibiotics, those prescribed immediate or delayed antibiotics experienced a reduction in poorer symptomatic outcomes: no antibiotics 398/587 (68%), immediate antibiotics 441/728 (61%), and delayed antibiotics 116/197 (59%); adjusted risk ratio (RR) (95% confidence intervals [CIs]): immediate RR 0.87 (95% CI = 0.70 to 0.96), P = 0.006; delayed 0.88 (5% CI = 0.78 to 1.00), P = 0.042 (Table 1). This finding was consistent when controlling for baseline severity.

Table 1.

Poorer global symptomatic outcome (either greater than median symptom severity in days 2–4 or greater than median duration of symptoms) related to antibiotic strategy and antibiotic type

| Antibiotic prescribing strategy | Poorer global symptomatic outcomean (%) | Univariate risk ratio (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for baseline severity and clustering (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for propensity score (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for propensity score in imputed dataset (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None n= 587 |

398 (67.80) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Immediate n= 728 |

441 (60.58) | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95), P = 0.002 | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.88), P<0.001 | 0.87 (0.70 to 0.96), P = 0.006 | 0.89 (0.80 to 0.98), P = 0.024 |

| Delayed n= 197 |

116 (58.88) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.97), P = 0.019 | 0.83 (0.73 to 0.95), P = 0.007 | 0.88 (0.78 to 1.00), P = 0.042 | 0.86 (0.74 to 0.97), P = 0.016 |

In the 1512 returning a symptom diary in which the prescribing strategy was detailed.

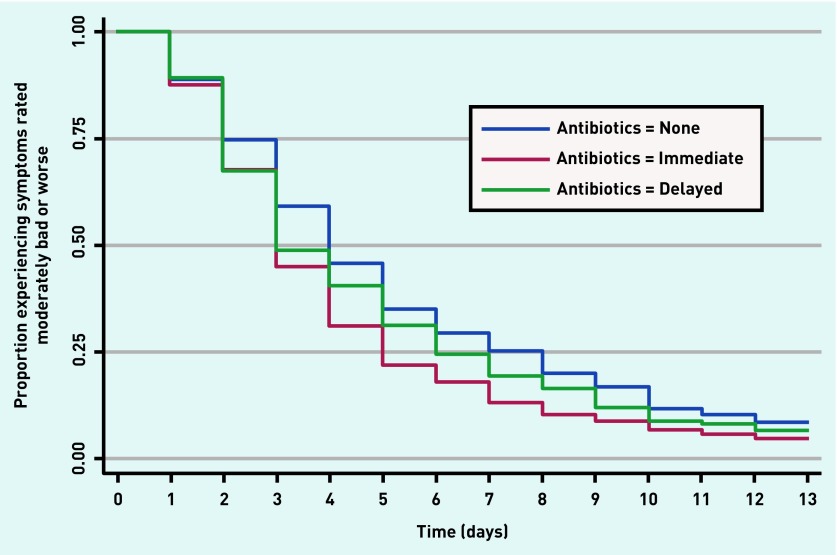

Secondary outcomes showed a reduction in symptom severity on days 2–4 (Table 2). On average, 1 day less of moderately bad symptoms was experienced by those prescribed an immediate antibiotic (no antibiotic: median 4 days, interquartile range (IQR) 2–7 days; immediate: median 3 days, IQR 2–5 days; delayed: median 3 days, IQR 2–6 days) (Table 3). Hazard ratio (HR) controlling for propensity score for immediate prescribing was 1.21 (95% CI = 1.07 to 1.38), P = 0.004, and the HR for delayed prescribing was 1.10 (95% CI = 0.92 to 1.33), P = 0.30 (Table 3). The duration of moderately bad symptoms is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Symptom severity on day 2–4 according to antibiotic prescription strategy

| Antibiotic prescribing strategy | Symptom severity, mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI), P-value | Difference controlling for clustering and, antibiotic type and baseline severity score (95% CI), P-value | Difference controlling for propensity score (95% CI), P-value | Difference controlling for propensity score in the imputed dataset (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (reference) n= 585 |

2.13 (1.24) | ||||

| Immediate n= 723 |

2.03 (1.20) | −0.10 (−0.23 to 0.03), P = 0.140 | −0.30 (−0.49 to −0.21), P = 0.001 | −0.22 (0.44 to −0.01), P = 0.040 | −0.22 (−0.43 to −0.01), P = 0.043 |

| Delayed n= 196 |

1.95 (1.19) | −0.17 (−0.37 to 0.02), P = 0.834 | −0.22 (−0.42 to −0.02), P = 0.034 | −0.26 (−0.45 to −0.7), P = 0.009 | −0.26 (−0.45 to −0.07), P = 0.008 |

SD = standard deviation.

Table 3.

Duration of moderately bad symptoms according to antibiotic prescription strategy

| Antibiotic prescribing strategy | Duration of moderately bad symptoms: median days (IQR) | Univariate hazard ratio, (95% CI), P-value | Hazard ratio controlling for clustering and baseline severity score (95% CI), P-value | Hazard ratio controlling for propensity score (95% CI), P-value | Hazard ratio controlling for propensity score in imputed dataset (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Antibiotic (reference) n= 587 |

4 (2–7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Immediate n= 728 |

3 (2–5) | 1.33 (1.18 to 1.50), P<0.001 | 1.37 (1.23 to 1.53), P<0.001 | 1.21 (1.07 to 1.38), P = 0.004 | 1.20 (1.07 to 1.3), P = 0.002 |

| Delayed n= 197 |

3 (2–6) | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.37), P = 0.120 | 1.16 (0.98 to 1.37), P = 0.084 | 1.10 (0.92 to 1.33), P = 0.300 | 1.10 (0.91 to 1.33), P = 0.316 |

IQR = interquartile range.

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients experiencing symptoms rated moderately bad or worse according to receipt of antibiotic prescription.

Evidence for a differential effect of antibiotic prescribing among those more likely to have bacterial infection

Although throat swabs were not collected, diary scores were used to predict the probability of streptococcal infection, and a subgroup of patients was created in whom bacterial infection was more likely as defined by a higher Centor Score (≥3) and FeverPAIN score (≥3).12 In this subgroup, the estimates of benefit were slightly greater than in the whole cohort for those given an immediate antibiotic prescription or delayed prescription (Tables 4 and 5). However, the difference between the subgroup and the main cohort was modest and statistically significant interactions were not powered for and were not found with the feverPAIN and Centor subgroups. The fact that those in these high-risk subgroups were overwhelmingly treated with immediate antibiotics further reduced the power of these analyses, particularly for the smaller numbers who were given delayed prescription. Individual secondary outcomes and point estimates for those at low/high risk of streptococcal infection are available from the authors on request.

Table 4.

Effect of probable streptococcal infection — results for participants with a FeverPAIN scorea of ≥3 according to antibiotic strategy

| Antibiotic prescribing strategy | Poorer global symptomatic outcome, n (%) | Interaction term (95% CI), P-value | Univariate risk ratio (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for baseline severity and clustering (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for propensity score (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for propensity score in imputed dataset (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (reference) n= 20 |

14 (70) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Immediate n= 281 |

152 (54.09) | 0.94 (0.84 to 1.05), P = 0.253 | 0.78 (0.57 to 1.05), P = 0.099 | 0.66 (0.52 to 0.84), P = 0.001 | 0.67 (0.52 to 0.87), P = 0.002 | 0.78 (0.58 to 1.04), P = 0.087 |

| Delayed n= 32 |

18 (56.25) | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.13), P = 0.711 | 0.80 (0.53 to 1.22), P = 0.306 | 0.79 (0.56 to 1.13), P = 0.198 | 0.68 (0.45 to 1.04), P = 0.493 | 0.73 (0.49 to 1.07), P = 0.108 |

FeverPAIN score: 1 point for each of fever in the past 24 hours, purulence, rapid (within 3 days) attendance, inflamed tonsils, and no cough or cold symptoms.

Table 5.

Effect of probable streptococcal infection – results for participants with a Centor scorea of ≥3 according to antibiotic strategy

| Antibiotic prescribing strategy | Poorer global symptomatic outcome, n (%) | Interaction term (95% CI), P-value | Univariate risk ratio (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for baseline severity and clustering (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for propensity score (95% CI), P-value | Risk ratio controlling for propensity score in imputed dataset (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (reference) n= 33 |

23 (69.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Immediate n= 374 |

207 (55.3) | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.14), P = 0.345 | 0.79 (0.62 to 1.01), P = 0.063 | 0.79 (0.62 to 1.00), P = 0.051 | 0.79 (0.63 to 1.00), P = 0.046 | 0.82 (0.65 to 1.03), P = 0.097 |

| Delayed n= 43 |

21 (48.8) | 0.83 (0.55 to 1.23), P = 0.349 | 0.70 (0.48 to 1.02), P = 0.066 | 0.72 (0.49 to 1.06), P = 0.096 | 0.64 (0.45 to 0.92), P = 0.015 | 0.65 (0.45 to 0.94), P = 0.021 |

Centor score: 1 point for each of tonsillar exudates, swollen tender anterior cervical nodes, lack of a cough, and history of fever.

DISCUSSION

Summary

This large cohort of patients presenting to general practice with acute sore throat enabled the authors to study the effect of prescribing antibiotics in routine practice on symptom severity and speed of illness resolution. Compared with a no antibiotic strategy, a delayed antibiotic strategy confers similar benefits to immediate antibiotics with regards to effects on global symptom outcome. Those prescribed immediate antibiotics experienced both a reduction in symptom severity on day 2–4 and a reduction in the duration of moderately bad symptoms of 1 day. Similar benefits were observed in those receiving a delayed prescription, although this study has limited power for some outcomes in this group.

Strengths and limitations

The study was designed using a simple clinical proforma to minimise selection bias and thus to produce a large generaliseable prospective cohort. Patients were recruited at the busiest seasons for respiratory illness, and, as with other studies of acute infection,13–15 documentation of the details of those not approached was poor as a result of time pressures (because time pressure to recruit also meant time pressure to document non-recruitment).

The large sample gathered in routine practice, along with the inclusion of diary data, enabled the study of different antibiotic strategies and duration of prescription on symptomatic outcomes and re-consultation, which is likely to reflect the real-life experience of patients. The prescription of antibiotics, however, is not at random and there is clear evidence of a greater propensity to prescribe for those with more severe symptoms at baseline (Appendix 1). Despite adjusting for propensity to prescribe and presenting outcomes controlled for baseline severity of symptoms, it is not possible to rule out residual confounding.

It is possible that patients who were given a prescription for antibiotics subsequently altered their reporting of symptom severity having had their illness ‘validated’ by the doctor or the converse in those not in receipt of a prescription. Any study using self-reported diary data may be open to such misclassification bias but if the reported symptoms are accepted at face value then the symptoms recorded in the diary will reflect the patient’s experience of illness. In this observational dataset it is not known how delayed prescribing was operationalised, but, regardless of this, a delayed prescription conferred similar symptomatic benefits to an immediate prescription, with lower prescription uptake.

Comparison with existing literature

In routine care in England, 48% of those presenting with an acute sore throat illness receive an immediate antibiotic prescription and 14% a delayed prescription.6 Antibiotics for acute sore throat are generally well targeted to those with the most severe symptoms and those most likely to benefit.6 In this current study, in the sample returning symptom diaries, 60% of those issued a delayed prescription reported using the prescription, which is greater than that reported in experimental studies.5 Overall use of antibiotics is similar in the US (60%),16 whereas in France and the Netherlands reported prescribing rates are lower (20% and 23%, respectively), although these are aggregated data for all respiratory consultations.17

As would be anticipated, there is some symptomatic benefit in those receiving an antibiotic comparable with that seen in systematic reviews and this effect is also seen in those in receipt of a delayed prescription.2,5

Although this study was not powered to find an interaction of the effect of antibiotic prescribing strategy with the likelihood of streptococcal infection, the point estimates for poorer symptomatic outcome with a no prescription strategy are more pronounced, which suggests that increased likelihood of streptococcal infection may make symptomatic benefit a little more likely when antibiotics are prescribed. Once again, there was no clear benefit from immediate antibiotics compared with delayed antibiotics in individuals more likely to have streptococcal infection.

Implications for research and practice

Systematic reviews have consistently demonstrated that antibiotics confer a modest benefit for symptom relief,2 and this study has confirmed this effect using evidence from routine practice. The authors have previously demonstrated that antibiotic prescriptions in routine general practice do appear to be targeted at those at greatest risk of streptococcal carriage according to baseline characteristics.6 Judicious use of antibiotics is an international priority,18 and there is potential to reduce the uptake of antibiotics through greater use of the delayed prescription technique or through non-prescription. Although adoption of the ‘non-prescribing strategy’ results in the lowest uptake of antibiotics,7 use of a delayed prescription may be a useful option where current prescribing rates are high or there is greater concern for complications. It is recognised that there is a trade-off between lower antibiotic prescribing and patient satisfaction with both doctors and practices,19 although clinical trials have not demonstrated large differences in satisfaction between immediate and delayed prescribing.5 There is also likely a trade-off between a global reduction in prescribing and an increased risk of septic complications, although the absolute increase is very small.20

Delayed prescribing in this study was targeted at those with intermediate symptom severity; however, trials of delayed prescribing in sore throat were not stratified by symptom severity and symptomatic outcomes were similar for all groups,5 hence it is unlikely that more widespread use of the delayed strategy would result in worse symptomatic outcomes. Caution must be exercised in those with greater probability of streptococcal infection and, although adverse outcomes in those with higher symptom scores using a delayed prescription were not demonstrated in this study, this may be due to lack of power. In one study, using a delayed strategy in combination with a symptom score to target antibiotics did result in both reduced antibiotic consumption and improved outcomes compared with empirical delayed prescribing, and this may be the optimal strategy.10 In routine practice as in trials, delayed prescribing offers comparable symptom control to immediate prescribing (this study), and the authors have previously shown it reduces re-consultation,6 and the risk of septic complications.8

In the full cohort, 14% of sore throat consultations concluded with the issue of a delayed antibiotic prescription. However, there is potential for higher rates to be achieved, for instance, only half of participating practices in this study reported using the delayed strategy. GPs have been shown to overestimate the patient demand for antibiotics,21 and the use of a delayed strategy would be one way of countering this overestimation. If most of those with intermediate symptom severity were offered a delayed prescription, the total uptake of antibiotics would be reduced with no anticipated adverse effects for symptom control, complications, or re-consultation.

Acknowledgments

The excellent running of the project in each centre was due to several individuals: in Oxford Sue Smith managed day-to-day data collection; in Cardiff Dr Eleri Owen-Jones managed the centre and Amanda Iles provided administrative support; in Exeter Ms Joy Choules was the Research Administrator and Ms Emily Fletcher helped with notes review; in Bristol the Research Administrator was Catherine Derrick. Thanks to the local GP champions who promoted the study and all the doctors, practices, and patients who agreed to participate.

Appendix 1. Baseline characteristics of the sample including those who returned the symptom diary

|

Total cohort n = 14 610 |

Patients who completed diaries and where prescribing strategy known n = 1512 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Not given antibiotics | Given antibiotics | Delayed antibiotics | Not given antibiotics | Given antibiotics | Delayed antibiotics | |

| Clinical assessment | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Number in cohort | 6057 | 6089 | 2464 | 587 | 728 | 197 |

|

| ||||||

| Severity of sore throat/difficulty swallowing on a 4-point Likert scale, mean (SD) | 2.93 (0.72) | 3.32 (0.63) | 3.06 (0.70) | 2.93 (0.68) | 3.35 (0.63) | 3.01 (0.68) |

|

| ||||||

| Severity of all baseline symptomsa on 4-point Likert scale, mean (SD) | 1.89 (0.39) | 2.19 (0.39) | 1.99 (0.40) | 1.88 (0.40) | 2.21 (0.38) | 1.95 (0.36) |

|

| ||||||

| Mean FeverPAIN score, mean (SD) | 0.33 (0.58) | 1.21 (1.09) | 0.72 (0.84) | 0.26 (0.52) | 1.19 (1.11) | 0.73 (0.84) |

|

| ||||||

| Prior duration in days, mean (SD) | 4.96 (6.48) | 4.61 (4.10) | 4.29 (3.34) | 4.75 (4.14) | 4.57 (3.39) | 4.17 (3.15) |

|

| ||||||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 34.72 (15.44) | 32.65 (14.18) | 34.07 (14.57) | 37.61 (15.47) | 36.04 (13.85) | 35.68 (14.15) |

|

| ||||||

| Female sex, n/N (%) | 3610/5243 (68.85) | 4147/6269 (66.15%) | 1770/2501 (70.77%) | 443/587 (75.47%) | 521/728 (71.57%) | 147/197 (74.62%) |

|

| ||||||

| Smoker, n/N (%) | 1016/5212 (19.49) | 1445/6240 (23.16%) | 481/2484 (19.36%) | 89/594 (15.24%) | 127/726 (17.49%) | 22/194 (11.34%) |

|

| ||||||

| Fever in last 24 hours, n/N (%) | 2279/4852 (46.97) | 4109/5704 (72.04%) | 1268/2317 (54.73%) | 261/585 (44.62%) | 515/724 (71.13%) | 113/197 (57.36%) |

|

| ||||||

| Temperature ºC (SD) | 36.66 (0.61) | 37.00 (0.75) | 36.77 (0.62) | 36.64 (0.61) | 36.99 (0.74) | 36.74 (0.50) |

|

| ||||||

| Pus on tonsils, n/N (%) | 376/5213 (7.21) | 3751/6232 (60.19%) | 654/2495 (26.21%) | 30/581 (5.16%) | 418/721 (57.98%) | 50/197 (25.38%) |

|

| ||||||

| Severely inflamed tonsils, n/N (%) | 86/4923 (1.75) | 1418/5855 (24.22%) | 178/2344 (7.59%) | 6/572 (1.05%) | 181/720 (25.14%) | 12/191 (6.28%) |

|

| ||||||

| Number of prior medical problems | 0.22 (0.49) | 0.24 (0.51) | 0.17 (0.43) | 0.28 (0.55) | 0.24 (0.51) | 0.17 (0.39) |

|

| ||||||

| Return within 4 weeks with new or worsening symptoms, n/N (%) | 803/4974 (16.14) | 864/5932 (14.57%) | 222/2382 (9.49%) | 107/564 (18.97%) | 101/694 (14.55%) | 24/186 (12.90%) |

|

| ||||||

| Return within 4 weeks with complications, n/N (%) | 75/4974 (1.51) | 78/5932 (1.31%) | 21/2382 (0.88%) | 12/564 (2.13%) | 8/694 (1.15%) | 3/186 (1.15%) |

|

| ||||||

| Individual complications, n/N (%) | ||||||

| Quinsy | 11/4974 (0.22) | 30/5932 (0.52%) | 6/2382 (0.26%) | 4/564 (0.71%) | 3/694 (0.43%) | 1/186 (0.54%) |

| Sinusitis | 23/4974 (0.46) | 12/5932 (0.21%) | 3/2382 (0.13%) | 2/564 (0.35%) | 0/694 | 0/186 |

| Otitis media | 31/4974 (0.62) | 27/5932 (0.47%) | 11/2382 (0.47%) | 5/564 (0.89%) | 5/694 (0.72%) | 2/186 (1.08%) |

| Celluliltis/impetigo | 10/4974 (0.20) | 9/5932 (0.16%) | 1/2382 (0.04%) | 1/564 (0.18%) | 0/694 | 0/186 |

Baseline severity comprised of: sore throat, difficulty swallowing, feeling generally unwell, headache, disturbed sleep, muscle ache, fever during illness, fever in the last 24 hours, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, cough during illness, vomiting, runny nose, earache, inflamed pharynx, inflamed tonsils, cervical glands.

Funding

The work was sponsored by the University of Southampton, funded by the Medical Research Council, and supported through service support costs by the National Institute for Health Research. Reference number G0500977. Neither sponsor nor funder had any role in specifying the analysis or in the write-up.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was given by the South West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (number 06/MRE06/17).

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Gulliford MC, Dregan A, Moore MV, et al. Continued high rates of antibiotic prescribing to adults with respiratory tract infection: survey of 568 UK general practices. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006245. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD000023. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Respiratory tract infections — antibiotic prescribing. Prescribing of antibiotics for self-limiting respiratory tract infections in adults and children in primary care. CG69. London: NICE; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashworth M, Charlton J, Ballard K, et al. Variations in antibiotic prescribing and consultation rates for acute respiratory infection in UK general practices 1995–2000. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(517):603–608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Little P, Williamson I, Warner G, et al. Open randomised trial of prescribing strategies in managing sore throat. BMJ. 1997;314(7082):722–727. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7082.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FD, et al. Antibiotic prescription strategies for acute sore throat: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spurling GK, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, et al. Delayed antibiotics for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(4):CD004417. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004417.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FD, et al. Predictors of suppurative complications for acute sore throat in primary care: prospective clinical cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f6867. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little P, Hobbs FD, Moore M, et al. PRImary care Streptococcal Management (PRISM) study: in vitro study, diagnostic cohorts and a pragmatic adaptive randomised controlled trial with nested qualitative study and cost-effectiveness study. Health Technol Assess. 2014;18(6):1–101. doi: 10.3310/hta18060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Little P, Hobbs FD, Moore M, et al. Clinical score and rapid antigen detection test to guide antibiotic use for sore throats: randomised controlled trial of PRISM (primary care streptococcal management) BMJ. 2013;347:f5806. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1(3):239–246. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8100100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Little P, Moore M, Hobbs FD, et al. PRImary care Streptococcal Management (PRISM) study: identifying clinical variables associated with Lancefield group A beta-haemolytic streptococci and Lancefield non-Group A streptococcal throat infections from two cohorts of patients presenting with an acute sore throat. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003943. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, et al. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of two prescribing strategies for childhood acute otitis media. BMJ. 2001;322(7282):336–342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7282.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Little P, Moore M, Kelly J, et al. Ibuprofen, paracetamol, and steam for patients with respiratory tract infections in primary care: pragmatic randomised factorial trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6041. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little P, Rumsby K, Kelly J, et al. Information leaflet and antibiotic prescribing strategies for acute lower respiratory tract infection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(24):3029–3035. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.24.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnett ML, Linder JA. Antibiotic prescribing to adults with sore throat in the United States, 1997–2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):138–140. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosman S, Le Vaillant M, Schellevis F, et al. Prescribing patterns for upper respiratory tract infections in general practice in France and in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(3):312–316. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies SC. Annual report of the Chief Medical Officer: volume one, 2011. On the state of the public’s health. London: Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashworth M, White P, Jongsma H, et al. Antibiotic prescribing and patient satisfaction in primary care in England: cross-sectional analysis of national patient survey data and prescribing data. Br J Gen Pract. 2016. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X688105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Gulliford MC, Moore MV, Little P, et al. Safety of reduced antibiotic prescribing for self limiting respiratory tract infections in primary care: cohort study using electronic health records. BMJ. 2016;354:i3410. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linder JA, Singer DE. Desire for antibiotics and antibiotic prescribing for adults with upper respiratory tract infections. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):795–801. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]