Abstract

Memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells exist in substantial numbers within hosts that have not been exposed to either foreign antigen or overt lymphopenia. These antigen-inexperienced memory-phenotype T cells can be divided into two major subsets: ‘innate memory’ T cells and ‘virtual memory’ T cells. Although these two subsets are nearly indistinguishable by surface markers alone, notable developmental and functional differences exist between the two subsets, which suggests that they represent distinct populations. In this Opinion article, we review the available literature on each subset, highlighting the key differences between these populations. Furthermore, we suggest a unifying model for the categorization of antigen-inexperienced memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells.

Lymphocytes within the peripheral T cell repertoire are classified as either naive or memory cells on the basis of their expression (or lack thereof) of various cell-surface markers and receptors. The expression of these surface markers correlates with various traits and functions that are specific to different T cell populations. For example, naive and central memory T (TCM) cells express both CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7) and CD62 ligand (CD62L; also known as L-selectin), which facilitate their surveillance of secondary lymphoid tissues. By contrast, other populations of memory T cells show increased expression of CD122 (also known as IL-2Rβ), CXC-chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) and the adhesion receptors CD44, CD11a and CD49d, all of which facilitate (among other things) their access to and responses within inflamed peripheral tissues. As these phenotypical changes occur in response to productive T cell receptor (TCR) signalling, the expression of these markers is classically viewed as a window into the history of a cell’s encounter with antigen in the periphery. However, although the majority of CD8+ T cells in an unmanipulated host (that is, an animal that has not been challenged with antigen) display a naive phenotype, there also exists a substantial population of CD8+ T cells (15–20% of total circulating CD8+ T cells) that express phenotypical markers of immunological memory. This has been known for some time1,2, but it was generally assumed to be the result of T cell responses to gut microbiota and/or exposure to unrelated pathogens. Although this is certainly true for some of the memory-phenotype T cells, present evidence indicates that the vast majority of these cells are antigen inexperienced, instead arising as a result of cytokine stimulation3.

Observations from lymphopenic animal models were crucial for establishing the settings in which these antigen-inexperienced memory cells form. CD8+ T cells transferred into a host deficient in T cells (genetically or as a result of irradiation) will undergo substantial rounds of proliferation4–7. This homeostatic proliferation is dependent on cytokines such as interleukin-7 (IL-7), as well as on the expression of other cytokines, most of which signal through the common γ-chain (also known as CD132)8–15. Although MHC molecules are required for naive T cells to undergo lymphopenia-induced homeostatic proliferation4,6,16, their role is mainly to provide a tonic stimulus through the TCR rather than an actual antigenic stimulus. Although a precise definition of a ‘tonic stimulus’ has never been fully clarified, it can be loosely defined as an interaction that does not lead to overt T cell activation but results in signalling that is necessary for the T cell to maintain responsiveness to subsequent activation17–19. Memory-phenotype cells that arise as a result of this form of homeostatic proliferation show consistently low expression of the α4 integrin CD49d; this is in sharp contrast to antigen-experienced memory T cells, which express high levels of CD49d5,6,20. A close examination of the memory-phenotype T cells present in lymphoreplete antigen-inexperienced hosts revealed their universal low expression of CD49d3. Not surprisingly then, these cells were subsequently found to be abundant in hosts containing progressively fewer foreign antigens; for example, pathogen-free mice, germ-free mice and even mice fed an elemental diet free of potential food antigens (REF. 21 and C. Surh, personal communication) all have robust populations of memory-phenotype CD49dlowCD8+ T cells3. From these data, we can conclude that the normal lymphoreplete host can support the development of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in the complete absence of overt antigen recognition.

Two major subtypes of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cell that have phenotypical similarities to the cells that undergo lymphopenia-induced homeostatic proliferation have been described in normal wild-type mice; these populations have been referred to as ‘innate CD8+ T cells’ (REFS 22–25) and ‘virtual memory T cells’ (TVM cells)26–30. Both populations seem to undergo relatively normal TCR rearrangement and thymic selection (with the exceptions noted below), and emerge with an unrestricted TCR repertoire. During or subsequent to their maturation into a naive single-positive CD8+ T cell, these cells receive the necessary signals, either within the thymus or in the periphery, to promote their differentiation into memory-phenotype cells. At first glance, they bear a striking resemblance to one another, which has led to some researchers dismissing the differences in their development and considering them as a single population31. However, recent data highlight sufficiently different developmental pathways and functional capabilities that warrant the treatment of these cells as distinct subsets28. It is worth clarifying that the antigen-inexperienced memory-phenotype cells that we discuss here are distinct from innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), natural killer T (NKT) cells and mucosa-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells; ILCs lack an antigen receptor32,33, whereas NKT cells and MAIT cells have an invariant or restricted TCR repertoire. Intraepithelial lymphocytes somewhat straddle the lines of these definitions, but as they are reasonably easy to distinguish from the other memory-phenotype cells and they have been well reviewed elsewhere34,35, we limit our discussion in this Opinion article to innate CD8+ T cells and TVM cells.

Innate memory T cells

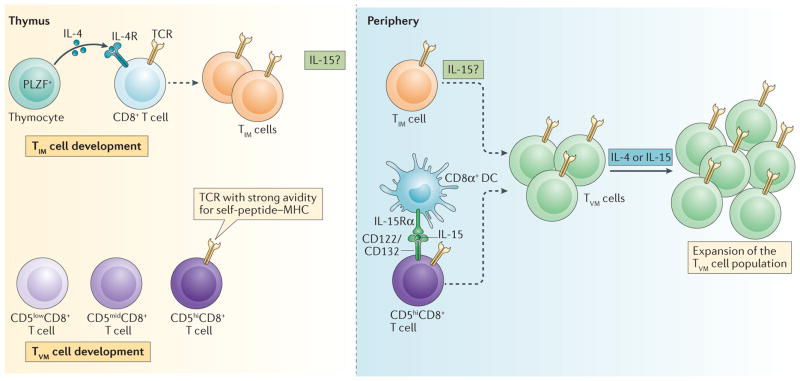

A unique population of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells (originally referred to as “innate CD8+ T cells” (REF. 23)) was initially discovered in mice lacking the TEC kinase IL-2-inducible T cell kinase (ITK). In these mice, the majority of CD8+ T cells in the thymus possess a memory phenotype (that is, they are CD44hiCD122hi)22,24. As more knockout mouse strains were found to have a similar phenotype (for example, those deficient for inhibitor of DNA-binding 3 (ID3), those deficient for Krueppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) and those deficient for CREB-binding protein (CBP; also known as CREBBP)), a pattern was deduced: these molecules are all involved in the upregulation of IL-4 or in the development of NKT cells25,26,30,36,37. Furthermore, the absence of these molecules favours either the production of IL-4 or the development of more NKT cells that express promyelocytic leukaemia zinc finger (PLZF; also known as ZBTB16) and produce large amounts of IL-4 (REFS 26,38). Subsequent studies revealed that the increase in the number of memory-phenotype cells is not CD8+ T cell intrinsic for these gene deficiencies, and is instead dependent on the excess IL-4 produced by NKT cells or PLZF+CD4+ T cells26,39. Although normal C57BL/6 (B6) mice have relatively few of these thymic innate CD8+ T cells, these cells account for a substantial percentage of total CD8+ T cells in wild-type BALB/c mice and form a population that is proportional in size to their populations of thymic PLZF+ IL-4-producing cells24,26,30,40. Although they have yet to be well described outside of the thymus in a wild-type mouse (BALB/c or B6), their presence in the periphery of hosts deficient in ITK or resting lymphocyte kinase (RLK; also known as CERK1) is IL-15 dependent22. In the convention of the nomenclature that has been used to describe other memory T cell subsets (for example, TCM cells, effector memory T (TEM) cells and resident memory T (TRM) cells (BOX 1)), we refer to these IL-4-dependent thymically derived cells as ‘innate memory T (TIM) cells’ for the remainder of this article (FIG. 1).

Box 1. Nomenclature for memory CD8+ T cell subsets.

Central memory T (TCM) cells: a population of memory T cells that express CD127 (also known as IL-7Rα), CD62 ligand (CD62L) and CC-chemokine receptor 7 (CCR7). TCM cells recirculate through both secondary lymphoid tissues and peripheral tissues; display self-renewing proliferative capacity; and both respond to and produce interleukin-2 (IL-2). This memory T cell subset is involved in protection against systemic infections.

Effector memory T (TEM) cells: a population of memory T cells characterized by moderate expression of CD127 and low levels of CD62L and CCR7. TEM cells recirculate mostly through peripheral tissues, and they display reduced proliferative capacity but rapid effector function (cytotoxicity and cytokine production). These cells protect peripheral tissues during infectious challenges.

Resident memory T (TRM) cells: these memory cells typically express high levels of CD69 and CD103, and low levels of CD122. As the name implies, they are non-recirculating memory cells, instead maintaining residence within specific tissue sites. This exclusive tissue-residence property makes them highly protective against repeated local infectious challenges.

Figure 1. A model of the development of innate memory and virtual memory T cells.

Innate memory T (TIM) cell development: in the thymus, naive CD8+ T cells are exposed to interleukin-4 (IL-4) derived from promyelocytic leukaemia zinc finger (PLZF)-expressing thymocytes and convert into TIM cells. In the periphery, the presence of TIM cells is dependent on IL-15, either because it is necessary for TIM cells to exit the thymus or because it is necessary for their survival once they are in the periphery. Although TIM cells in the thymus do not express T-bet, all antigen-inexperienced memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in the periphery (defined by a CD44hiCD49dlowCD122hi phenotype) express both eomesodermin (EOMES) and T-bet. This suggests that the majority of TIM cells in the periphery have encountered IL-15, which results in their phenotype becoming indistinguishable from that of virtual memory T (TVM) cells. TVM cell development: naive CD8+ T cells expressing T cell receptors (TCRs) with a strong affinity for self-peptide–MHC complexes express high levels of CD5, exit the thymus and convert into TVM cells following their interaction with IL-15 that is trans-presented by lymphoid-resident CD8α+ dendritic cells (DCs). IL-4 may act on existing TVM cells to further expand the TVM cell population, which depends on IL-15 for survival. Dashed arrows indicate differentiation. IL-4R, IL-4 receptor.

TVM cells

Outside the thymus, memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells have been noted in the secondary lymphoid organs of unmanipulated, specific-pathogen-free hosts for some time. These cells were often referred to simply as ‘endogenous memory’ T cells41 and were assumed to be the result of T cell responses to environmental antigens of one kind or another. Using tetramer pulldown assays (which use MHC tetramer staining and a magnetic bead enrichment method3,42) to isolate the nominal antigen-specific repertoire, we and our collaborators found memory-phenotype cells within the pre-immune repertoire of T cells specific for antigens that had never before been encountered by the host3. These cells had the same phenotype as those that have undergone lymphopenia-induced homeostatic proliferation (that is, they were CD44hiCD122hiCD49dlow), which suggested that their development was dependent on cytokine stimuli and not on antigen. The subsequent identification of these cells in hosts free of microbiota, pathogens and even food-related antigens solidifies this conclusion (REF. 21 and C. Surh, personal communication). Since the original description of TVM cells, we and others have determined that they are present in IL-4-deficient hosts27,43, but are absent in mice deficient for either IL-15 or the transcription factor eomesodermin (EOMES)27. As these cells were phenotypically similar to those undergoing ‘space filling’ homeostatic proliferation in a lymphopenic environment, the term ‘virtual memory’ seemed an appropriate, if somewhat ‘tongue-in-cheek’, name for this particular subset given the use of this term in computing to describe a form of memory that is based on an alternative use of disc space (FIG. 1).

A distinction with a difference

It is reasonable at this point to question whether a TIM–TVM cell paradigm propagates a distinction without a difference. Although some differences will already be evident, the two types of cell are highly similar in terms of their phenotype and their capacity to protect a host against infectious challenge27,30,44. Indeed, although TIM cells within the thymus express increased levels of CD49d relative to the TVM cells found in the periphery27, it becomes nearly impossible to differentiate between the two subsets using this marker once the cells are outside the thymus. In addition, although TVM cells are still present in IL-4-deficient mice, they express high levels of the IL-4 receptor28, which suggests that even if IL-4 is unnecessary for their development, they are most probably still influenced by IL-4-induced signalling. Confusing things further, although TIM cells are ablated in the absence of IL-4 regardless of the background mouse strain, the influence of IL-4 and IL-15 on TVM cells in the periphery varies considerably depending on the strain of mice used45,46. In an effort to make sense of these complexities and provide support for instigating a TIM–TVM cell paradigm, we present a comprehensive assessment of the differences between TIM and TVM cells (FIG. 2; TABLE 1), an overall and (hopefully) unifying model of the developmental interplay between the subsets (FIG. 1), and support for the translation of these differences beyond the mouse into the setting of human immunology (TABLE 1).

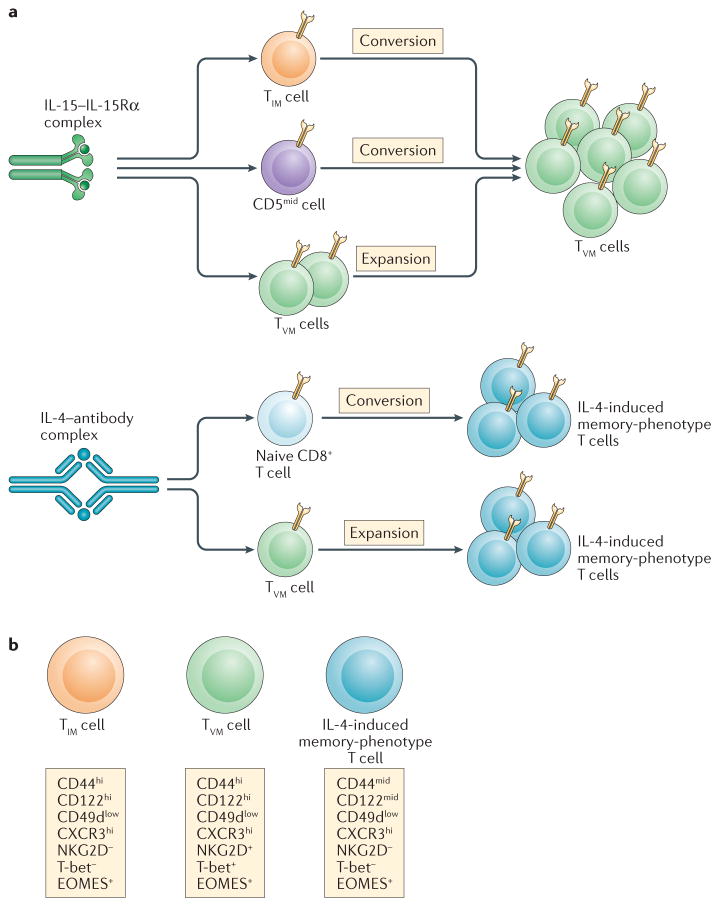

Figure 2. The influence of cytokine complexes on naive and memory CD8+ T cell subsets.

a | Interleukin-15 (IL-15)–IL-15 receptor subunit-α (IL-15Rα) complexes induce a substantial expansion of cells with a virtual memory T (TVM) phenotype. This most likely occurs through the combined effects of (i) stimulation and expansion of thymic-emigrant innate memory T (TIM) cells, (ii) the conversion of naive CD8+ T cells that have more moderate levels of CD5 expression (with lower self-affinity) and (iii) the expansion of the pre-existing TVM cell pool. By contrast, IL-4 cytokine–antibody complexes promote the conversion of both naive and TVM cells into distinct populations of ‘IL-4-induced’ memory-phenotype cells, expanding them in the process. b | The main phenotypical characteristics of these three memory-phenotype populations (namely, TVM cells, TIM cells and ‘IL-4-induced’ memory-phenotype cells) are shown. CXCR3, CXC-chemokine receptor 3; EOMES, eomesodermin.

Table 1.

A comparison of the distinguishing characteristics of antigen-inexperienced memory-phenotype cells

| Memory CD8+ T cell subset |

Phenotype | Location | Precursor | Cell dependence |

Cytokine dependence: development |

Cytokine dependence: maintenance | Functions | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse virtual memory T cell |

|

|

CD5hiCD8+ T cells | CD8α+ dendritic cells | IL-15 | IL-15 |

|

3,27,28, 43,44 |

| Mouse innate memory T cell |

|

Thymus and periphery | Unknown | Thymic PLZF+ cells | IL-4 | IL-15 |

|

26,29, 30,84 |

| Human innate-like memory CD8+ T cell |

|

|

Unknown | Unknown | IL-15-experienced phenotype (CD5lowEOMES+) | IL-15-responsive phenotype (CD122hiEOMES+CD27−) |

|

28,69,72, 73,85 |

CXCR3, CXC-chemokine receptor 3; EOMES, eomesodermin; IFNγ, interferon-γ; IL, interleukin; KIR, killer immunoglobulin receptor; PLZF, promyelocytic leukaemia zinc finger.

Sites of development

One of the most salient (and easily distinguishable) differences between TIM and TVM cells is their distinct sites of origin: TIM cells develop in the thymus, whereas TVM cells develop in the periphery29,43 (FIG. 1; TABLE 1). As for the precursors of each cell type, it is unclear whether or not the conversion of a developing CD8+ T cell into a TIM cell within the thymus is purely stochastic or based on an as-yet-unidentified property of the T cell. By contrast, we recently showed that the naive T cells with the highest levels of CD5 expression (that is, those with a CD44lowCD5hi phenotype) are the most likely to convert into TVM cells in the periphery28. CD5 is a surface molecule for which the expression levels directly correlate with the strength of signal that a developing T cell receives through its TCR upon positive selection by self-peptide–MHC in the thymus. Thus, CD5 expression is an effective proxy for the T cells within the repertoire that have the greatest affinity for self-ligands. CD5 was previously shown to stratify the homeostatic proliferation potential of naive T cells within a lymphopenic environment, with the T cells that show the highest CD5 expression being the most proliferative. Thus, it was perhaps not surprising to find that CD5hi naive T cells are also the most likely to convert into a TVM cell phenotype within lymphoreplete hosts27,28 (FIG. 1). The differential responsiveness of naive CD8+ T cells based on their CD5 levels adds to a growing number of studies showing that thymic selection produces a far more heterogeneous naive T cell pool than was previously appreciated. By performing RNA sequencing, Stephen Jameson and colleagues47 conclusively demonstrated this heterogeneity between CD5hi and CD5low T cells, with predominant differences being in the expression of factors that are involved in sensing and responding to the inflammatory environment (for example, receptors such as CXC-chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3) and CD122, and the transcription factor EOMES)47. Our data confirmed their initial results and extended this transcriptional analysis to include TVM cells, showing that the expression of receptors sensitive to inflammation increases even further as cells enter the TVM cell pool27. It remains to be determined whether the transcriptional profiles of these subsets will be useful in establishing a definitive precursor of TIM cells as well.

Cytokine dependency

In conjunction with these sites of origin, the story of TIM cell and TVM cell development is largely a tale of two cytokines: IL-4 and IL-15. It is fair to say that the major difference between these two cell types is in the part played by IL-4: TIM cell development is abrogated in the absence of IL-4, whereas TVM cell development is not. This requirement for IL-4 was demonstrated in the earliest publications, in which mice deficient in ITK, ID3 or RLK were found to produce increased numbers of TIM cells compared with wild-type controls22,24. In these strains, the loss of IL-4, PLZF or NKT cells resulted in the loss of thymic TIM cells26,37. The connection between TIM cells and IL-4, PLZF and NKT cells is not limited to these mutant strains, as the size of the TIM cell pool can also be accurately predicted from the amount of IL-4 produced by NKT cells in wild-type mouse strains38,40. Thus, an obligate connection exists between intrathymic levels of IL-4 and TIM cell development (FIG. 1).

By contrast, IL-4 deficiency has a more limited impact on the appearance of TVM cells in the periphery. Whereas the loss of IL-4 produces a small, but reproducible and statistically significant, decrease in the frequency of TVM cells, 80–90% of the TVM cell population remains intact in the absence of IL-4 (REFS 27,43,48) (note that these studies were conducted in B6 mice; see the ‘Mouse strains’ section for strain considerations). However, cells with a TVM cell phenotype are absent from the periphery of IL-15-deficient mice and are also not detected in mice with CD122-deficient T cells27. Experiments that used an IL-15-reporter mouse developed by Philippa Marrack and colleagues showed that basic leucine zipper transcriptional factor ATF-like 3 (BATF3)-dependent dendritic cell (DC) subsets are the predominant producers of IL-15 in the steady state27. By comparing TVM cell development in BATF3-deficient mice on different background strains (B6/129 versus B6 background), we identified CD8α+ lymphoid-resident DCs as being the cells that are largely responsible for TVM cell development in the periphery27. Productive IL-15 signalling for TVM cell development requires EOMES27,49, and results in the increased expression of both EOMES and T-bet. Curiously, however, T-bet expression is not necessary for TVM cell development, and this transcription factor may even inhibit their development, as T-bet-deficient mice often have elevated frequencies of TVM cells (R.M.K., unpublished observations). Regardless, the loss of IL-15 expression (in B6 mice) has essentially the same impact on TVM cell development in the periphery as does the loss of IL-4 on TIM cell development in the thymus.

That said, although the peripheral pool of TVM cells is not IL-4 dependent, it is inarguably IL-4 sensitive. For one, it is likely that IL-4-dependent TIM cells from the thymus seed the periphery at a rate that is yet to be determined. As cells derived from TIM cells and TVM cells seem to have the same phenotype once they are in the periphery (that is, a CD44hiCD122hiCD49dlow phenotype), the degree to which the number of cells with a TVM phenotype decreases in IL-4-deficient hosts could mostly reflect the contribution of TIM cells to the periphery (FIG. 1). In addition, and not exclusive of this, IL-4 could also more directly influence TVM cell development. It is unclear at this point whether IL-4 is in some way developmentally necessary for a full complement of TVM cells; whether IL-4 in the periphery can convert naive T cells into TVM cells (analogously to the role of IL-15 in TVM cells); and whether IL-4 expands the existing TVM cell population (FIG. 1). Evidence for each possible model has been published, although so far no data conclusively distinguish between these non-exclusive alternatives. First, it is conceivable that thymic IL-4 ‘programmes’ a developing T cell in such a way that, once it becomes mature, the circulating naive T cell is more sensitive to the peripheral signals that convert naive CD8+ T cells into TVM cells, potentially by tuning its responsiveness to IL-15. For example, IL-4 might help to induce increased expression of EOMES and/or CD122 in a developing T cell in the thymus, making the cell more sensitive to receiving IL-15 stimulation in the periphery. Indeed, type I interferon (IFN) has been shown to influence the size of the peripheral TVM cell pool, most likely through just such a mechanism49. Were this to be the case, however, one might expect the TVM cells in IL-4-deficient mice to show reduced intracellular expression of EOMES, as is seen in T cells defective in type I IFN signalling49. As the expression of EOMES is equivalent in TVM cells from IL-4-deficient and those from wild-type mice (REF. 27 and R.M.K., unpublished observations), this seems unlikely.

Second, peripheral IL-4 may directly convert some naive T cells into TVM cells independently of IL-15. Some data are consistent with this, including the fact that peripheral TVM cells are always reduced in number in IL-4-deficient mice. In this model, IL-4 is required to drive the production of all TIM cells in the thymus and a proportion of TVM cells in the periphery of wild-type mice. The loss of IL-4 would then lead to the ablation of TIM cell production in the thymus and a loss of only the IL-4-dependent TVM cells in the periphery, which would leave behind IL-4-independent TVM cells. Potentially supporting this model are data showing that an excess of IL-4 in the periphery (either in mice that overexpress IL-4 or in mice administered exogenous IL-4 complexes) induces the proliferation of naive T cells and their upregulation of some phenotypical markers of memory, most notably EOMES and CXCR3 (REFS 48,50). However, two points are noteworthy with regard to this possible role of IL-4 in TVM cell development. First, the fact that TVM cells are absent from IL-15-deficient mice, in which IL-4 expression is normal, calls into question the capacity of IL-4 alone to promote the development of TVM cells in the periphery. Second, the stimulation of naive cells with excess IL-4 induced T cell proliferation but not the upregulation of established markers of antigen-inexperienced memory T cells such as CD122 or CD44 (REF. 51). Similarly, the transfer of naive CD8+ T cells into mice overexpressing IL-4 induces their acquisition of an EOMEShiCD49dlow phenotype, but again their expression of CD122 remains low48. Consistent with these results, in vivo administration of high doses of IL-4 in our laboratory induces the proliferation of both naive and memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in vivo, but lowers their expression of both CD44 and CD122 (J.T.W., unpublished observations). This loss of CD44 and CD122 is in sharp contrast to the influence of excess IL-15 stimulation, which leads to the substantial upregulation of both of these markers27,28 (FIG. 2). This is not to dispute the fact that high-dose IL-4 stimulation of naive-phenotype CD8+ T cells in the periphery creates memory-phenotype cells of some sort, but their consistent lack of canonical TVM cell markers, such as CD44 and CD122, makes them difficult to include in the TIM–TVM cell paradigm. Indeed, the importance of peripheral IL-4 was highlighted in independent reports from the laboratories of Steve Jameson and David Hildeman45,46, in which the authors convincingly showed that the absence of IL-4 has dramatic effects on the overall development of functional CD8+ T cell memory in response to infectious challenge.

Lastly, and in our view the most probable explanation, physiological levels of IL-4 (as opposed to the high doses of IL-4 used in the experiments described above) may exert effects on TVM cells in the periphery by further expanding the pre-existing TVM cell pool. The fact that TVM cells have significantly elevated expression of IL-4 receptor subunit-α (IL-4Rα; compared with naive T cells) suggests that IL-4 can stimulate and expand those TVM cells that have already formed in response to IL-15 (REFS 28,51,52). Given this, we suggest that the influence of IL-4 on peripheral TVM cells in wild-type mice is most likely to be the result of IL-4-induced thymic TIM cell transit to the periphery combined with some degree of IL-4-induced proliferation of established TVM cells (FIGS 1,2). Whether the effect of IL-4 on TVM cells is stochastic, or if the TVM cell pool can be subdivided into cells that are more or less susceptible to proliferating in response to IL-4 (analogous to what is seen for CD5 levels and IL-15 sensitivity), remains to be determined.

It is worth mentioning that TIM cells have also been shown to be IL-15 dependent (in B6 mice; see the ‘Mouse strains’ section below), further complicating the hierarchy of cytokine dependencies for this cell type. Although this property of TIM cells has not been extensively explored, IL-15 may have important roles in the survival of TIM cells and/or their transit from the thymus into the periphery22 (FIG. 1).The transcription factor KLF2 is required for T cells to egress from the thymus, as KLF2 regulates the expression of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1)39,53. KLF2 is also responsible for regulating S1P1 expression in activated CD8+ T cells and memory CD8+ T cells, specifically in response to IL-15 (REF. 54). Given these data, it is possible that TIM cells require IL-15 stimulation to increase KLF2 and S1P1 expression in order to gain access to the thymic efferent lymphatics. IL-15 is also well known for its capacity to influence memory T cell survival55, so although the egress of TIM cells may well be intact in the absence of IL-15, their survival may not. Fortunately, these aspects of TIM cell development are highly amenable to study and will certainly be ascertained in the near future.

Functions of TIM and TVM cells

Both TIM and TVM cell subsets are poised to produce IFNγ when they come into contact with their cognate antigen. As a result, both enact antigen-specific immune protection against infection far better than do naive CD8+ T cells27,28,44. However, TVM cells have two additional functions that are yet to be demonstrated in TIM cells: namely, antigen-independent cytokine production and lytic activity (TABLE 1). Similarly to antigen-experienced memory CD8+ T cells, TVM cells can produce IFNγ when stimulated with a combination of IL-12, IL-15 and IL-18. This occurs in the absence of any antigen encounter and facilitates a more innate-like role for TVM cells in response to the inflammatory milieu alone. TIM cell express EOMES at levels similar to those seen in TVM cells22,25,26,38,39, but they do not express T-bet26,38,39, which may be a factor in determining whether or not they possess a similar capacity to produce IFNγ in response to stimulation with inflammatory cytokines alone. Regardless, it is highly unlikely that TIM cells display the same bystander killing function as TVM cells. TVM cells express a range of molecules (for example, NKG2D, IL-18 receptor, signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4) and granzyme B) that Martin Prlic and colleagues56 showed can facilitate bystander (antigen-nonspecific) killing by CD8+ T cells. The expression of these effector molecules facilitates TVM cell-mediated bystander protection against infectious agents28. Underscoring what may be the most important difference between the TIM cell and TVM cell subsets, TIM cells do not express NKG2D30,50. Thus far, only TVM cells are known to be capable of both cytokine production and target recognition and killing independently of antigen recognition. Although not associated with any specific effector function, TVM cell populations also expand in the host during ageing and show preferential trafficking to the liver28. Although antigen stimulation may help to facilitate the persistence of TVM cells over time57, both of these features of TVM cells are also probably related to their responsiveness to IL-15. IL-15 induces the long-term survival of memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and the elevated CD122 expression of TVM cells will almost certainly provide them with a competitive advantage for responding to IL-15. Furthermore, IL-15 is highly expressed in the liver58. Given the high frequency of TVM cells in the liver, it probably serves as a site where TVM cells can be most efficiently stimulated over time.

In addition to TVM cells, NK cells, MAIT cells, γδ T cells and NKT cells are also enriched within the liver compared with in the blood. Interestingly, all of these populations display forms of innate-like behaviour that are not displayed by conventional αβ T cells59,60. Part of the shared functionality of these cells is probably due to the physiology of the liver. The portal vein supplies 80% of the blood flow into the liver, bypassing the spleen (the remaining 20% is arterially supplied)61. Thus, the liver is a front-line immune surveillance organ in which dietary antigens and pathogens from the gastrointestinal tract are often first encountered. Chronic exposure to metabolites derived from the gut flora from this portal blood flow creates a tolerogenic environment in the liver, in part owing to the induction of IL-10 production61–63. It has been postulated that the presence of so many innate-like lymphocytes, which have less strict requirements for inflammatory cytokine production than do conventional αβ T cells, may help to overcome this tolerogenic milieu by promoting the maturation of antigen-presenting cells59. For the purposes of host protection, the importance of the liver in controlling infection is shown by the increased morbidity and mortality seen in mice that lack Kupffer cells (liver-resident macrophages), and by the fact that this increase is not seen in splenectomized mice after Borrelia burgdorferi infection64. Furthermore, many chronic viral infections and particular developmental stages of parasites reside within the liver. These pathogens are difficult to clear for myriad reasons, yet it seems likely that inflammatory cytokine production and bystander killing by TVM cells, in the absence of antigenic stimulation, could help to mount a more productive response against these difficult-to-clear pathogens.

Aside from their capacity to produce IFNγ in response to inflammatory cytokines30, considerably fewer details are known about the functions of TIM cells. The reliance of TIM cells on IL-4 for their development might suggest that this population may be useful in host defence during type 2 immune responses (for example, in immune responses against helminths) in which IL-4 has an important role; this argument is bolstered further by the induction of a memory-like phenotype in peripheral T cells after the injection of IL-4 (REFS 48,50,65). If TIM cells do have a role in type 2 immune responses, there is a possibility that TVM cells and TIM cells act in complementary ways to each other, forming a type 1–type 2 axis within the antigen-inexperienced CD8+ T cell populations. That said, this is currently purely speculative, and firm conclusions about the functional properties and potential benefits of TIM cells and IL-4-induced memory cells await further experimentation.

Lastly, regardless of their origin, the presence of antigen-inexperienced memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells specific for nominal antigen necessitates some reorientation of our views of ‘primary’ T cell responses to pathogens. It is now clear that essentially every T cell response, regardless of prior antigen exposure, is composed of both naive and memory responders. Aside from adding to the expanding complexity and heterogeneity of the primary immune response28,47, this has already been shown to have an impact on the formation of antigen-specific memory. Stephen Jameson and colleagues44 showed that TVM cells preferentially become TCM cells (as opposed to TEM cells) after the resolution of a primary immune challenge. More recently, the laboratories of Stephen Jameson and David Hildeman separately showed differences in the formation of CD8+ T cell memory between wild-type and IL-4-deficient BALB/c mice45,46. Importantly, they showed that the impact of IL-4 occurred before pathogen exposure, which indicates that the alteration in conventional memory T cell subsets was directly related to the participation of TIM and TVM cell subsets. TVM cells behave in the same way to a secondary challenge as do cells that have followed the classical naive-to-TCM cell pathway44, so it is not clear how far beyond the development of ‘primary immune memory’ (that is, the memory population formed after a single antigen encounter) the influence of TIM and TVM cells extends. Regardless, the universal presence of these cells in almost all model systems (even in recombination-activating gene (RAG)-deficient TCR-transgenic mice3,27) mandates that they are taken into account.

Mouse strains

It is important to note that the vast majority of studies examining both TIM and TVM cell development and function have been performed in B6 mice. Although little has been done in other strains, such as the BALB/c strain, early indications are that both similarities and differences exist. First, the relationship between PLZF, NKT cells and IL-4 and TIM cell development that was originally identified in B6 mice seems to also hold true in the BALB/c strain. The BALB/c strain and other strains that have elevated thymic levels of PLZF, NKT cells and IL-4 have correspondingly increased populations of TIM cells. Similarly to B6 mice, the loss of IL-4 in BALB/c mice also ablates TIM cell development26,38. Thus, although the magnitude of TIM cell development is determined by the mouse strain, the mechanisms that drive TIM cell development seem to be the same.

Second, in both B6 and BALB/c mice, the loss of TIM cells in the thymus does not lead to a complete loss of TVM cells in the periphery. IL-4 deficiency in BALB/c mice does produce a greater reduction in TVM cells in the periphery than is seen in IL-4-deficient B6 mice; whereas 80–90% of the TVM cell population in the periphery of B6 mice is intact, the numbers of TVM cells in IL-4-deficient BALB/c mice are reduced to ~30–50% of the levels seen in wild-type BALB/c mice45,46. Given the increased thymic levels of PLZF and IL-4 in BALB/c mice, TIM cells would be expected to contribute more to the peripheral pool of memory-phenotype cells in the BALB/c strain than in the B6 strain. Furthermore, if the increased levels of IL-4 in the thymus of BALB/c mice correlate with increased systemic IL-4 levels, this would cause more proliferation of TVM cells in the periphery of BALB/c mice than in that of B6 mice. Thus, a greater influence of IL-4 on TVM cell frequency in the BALB/c host than in the B6 host is perhaps not surprising. However, the TVM cell frequency in an IL-4-deficient BALB/c is far from zero, which indicates that cytokines other than IL-4 are responsible for the development of cells with a TVM phenotype in the periphery. The obvious candidate is of course IL-15, but the available data suggest that this cytokine does not have the same obligate role in TVM cells in BALB/c mice as it does in B6 mice. A recent report from David Hildeman and colleagues45 compared antigen-specific TVM cells in the periphery of wild-type, Il4−/−, Il15−/− and combined Il4−/−Il15−/− mice on the BALB/c background. Surprisingly, although the percentage of bulk TVM cells was somewhat reduced (D. Hildeman, personal communication), IL-15-deficient hosts showed little reduction in the number of TVM cells specific for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus nucleoprotein.

Although more analysis of these hosts is necessary, at the very least these data indicate far less of a reliance on IL-15 for TVM cell development in the BALB/c strain than in the B6 strain. Curiously, this result is in line with the expression of CD122 in the two strains; CD122 is expressed at much higher levels in B6 mice than in the BALB/c strain (S. Jameson and D. Hildeman, personal communication). Given the reduced expression of this IL-15 receptor subunit in BALB/c mice, it is perhaps not surprising that the presence or absence of TVM cells (which in the BALB/c mouse are CD44hiCD122hiCXCR3hi (REF. 46)) is less dependent on IL-15. In this regard, it is interesting to note that the major cytokines controlling homeostatic proliferation in both lymphopenic and lymphoreplete hosts all utilize the common γ-chain receptor subunit that is used for signalling by IL-2, IL-4, IL-7 and IL-15. Thus, perhaps strain differences in the production of TVM cells are based on which common γ-chain-containing receptors are most highly expressed or used in that background strain. This remains speculation until the relevant cytokines and their receptors can be more conditionally and temporally controlled in the BALB/c strain, and their peripheral compartments examined for the gain or loss of TVM cells.

Human TVM cells

Although memory T cell subsetting in mice has become something of a ‘cottage industry’ in and of itself, a reasonable test of physiological and clinical relevance is whether or not an identified subset has a corresponding correlate in humans. Definitive proof of identical human equivalents of TIM and TVM cells is yet to be produced, but reasonable correlates have been identified. Although almost all T cells in human cord blood have a naive phenotype, a substantial number of TIM-like cells were identified in spleen samples obtained from pre-term infants30,66,67. Furthermore, PLZF is highly expressed in both thymic and splenic human fetal CD4+ T cells67,68, consistent with the possibility of TIM cell development, IL-4-mediated expansion of TVM cells or both scenarios. Features of these fetal cells, such as EOMES expression and rapid IFNγ production67, are again consistent with either TIM or TVM cell classifications.

In cord and adult blood, a human cell population that has phenotypical and functional similarities (including in terms of trafficking behaviour) to mouse TVM cells was recently described28,69 (TABLE 1). Unlike in the mouse, in which CD5 levels are essentially fixed upon egress from the thymus70,71, CD5 expression on human T cells decreases as the T cell undergoes differentiation72. Furthermore, T cells that express the lowest levels of CD5 are the most sensitive to IL-15 and have the highest expression of CD122 (REF. 73). A small but reproducible population of CD5lowCD122hi T cells can readily be found within the human CD45RA+CD27− compartment (with high CD45RA expression and a lack of CD27 expression being canonical markers of naive and memory T cells, respectively74). In addition, these CD5lowCD122hi cells display the following features: first, increased expression of NUR77 (also known as NR4A1), a molecule for which expression correlates with the strength of TCR signal the cell receives75 (suggesting a higher basal TCR–MHC self-affinity); second, expression of NK cell-associated markers, such as NKG2A, killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor 3DL1 (KIR3DL1) and KIR3DL2 (REF. 69); and third, expression of both EOMES76 and T-bet28,69. Collectively, these markers indicate a human cell that possesses the mouse TVM cell-like characteristics of a higher affinity for self, a responsiveness to IL-15, and a capacity for bystander cytokine and killing functions28. This phenotype places these putative TVM cells squarely within the human CD8+ T cell subset known as terminally differentiated effector memory cells re-expressing CD45RA (TEMRAs; also known as terminal effectors). As can be surmised from the name, these cells are believed to be largely terminally differentiated. Indeed, their short telomeres — the shortest found among human CD8+ T cell subsets77 — is consistent with this. However, we and others noted the presence of a substantial pool of CCR7+ T cells that are included in many analyses of TEMRAs69. Furthermore, this CCR7+ population is where the majority of EOMES+ cells are found, and these CCR7+ cells both increase in number with age and show increased trafficking to the liver with age (J.T.W., unpublished observations). Lastly, these cells can be found in both adult and cord blood28. Although this is not formal proof, it is at least consistent with the idea that at least some of the cells in this population could be derived from antigen-inexperienced precursors.

Antigen-inexperienced CD4+ TVM

We have focused on CD8+ T cells for the main reason that antigen-inexperienced memory CD4+ T cells have yet to be described in mice. Although memory CD4+ T cells are found in unmanipulated mice, all of these are CD49dhi (REF. 27), which indicates that they have developed as a result of antigen encounter. Perhaps most tellingly, MHC class II-restricted TCR-transgenic mice have no CD44hi T cells in the absence of secondary TCRs (that is, when maintained on a RAG-knockout background)42, whereas the majority of MHC class I-restricted TCR-transgenic mice do3. This is consistent with the interpretation that memory CD4+ T cells do not arise in an antigen-inexperienced fashion within a wild-type lymphoreplete mouse. Although the reasons for this are unknown, it may well be related to the substantially lower expression of CD122 on CD4+ T cells27 relative to CD8+ T cells, which makes CD4+ T cells less susceptible to IL-15-mediated proliferation, much like the CD8+ T cells in the BALB/c host. While this would seem to suggest that all memory-phenotype CD4+ T cells are the result of antigen experience, the possibility remains that differentiating the memory CD4+ T cell populations in mice requires different markers. Although the search for CD4+ TVM cells in mice has not been successful so far, there is reason to believe that these cells may exist in humans. Recent studies from the laboratory of Mark Davis78 suggest that some form of antigen-inexperienced CD4+ T cells most likely exist, and it is now a question of refining the search, as one group has done by analysing the complementarity-determining region sequences of naive and memory-phenotype CD4+ T cells79.

Concluding remarks

A reasonable conclusion from the data on both TIM cells and TVM cells is that the host seems ‘determined’ to develop memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in the presence or absence of antigen exposure. As with any biological phenomenon, this is either because evolution favoured the creation of these cells to benefit the organism or because they are the epiphenomenal result of some other evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Any answer to this question is clearly speculative, but the benefits of the spontaneous production of memory-phenotype T cells with non-antigen-dependent protective capacity seem obvious. Organisms go through periods of lymphopenia, both during the neonatal period and after thymic involution2,80,81. The organism is at greater risk from infection during these time periods; the fewer T cells that an organism has at its disposal, the less likely the organism is to have T cell clones that are specific for any given pathogen, which increases the need for a broader T cell response57,82. The production of TIM cells and TVM cells would be evolutionarily beneficial as a mechanism for generating CD8+ T cells that can respond robustly in conditions in which the T cell compartment is compromised. The high expression of chemokine receptors (namely, CXCR3) and adhesion receptors (namely, CD11a, CD44 and LY6C) on TIM and TVM cells suggests that they would be among some of the first cells to be recruited to sites of infection. The ability of TVM cells to carry out bystander killing makes them even better suited to early pathogen control. As infections are increasingly encountered over time, it is in the best interests of the organism to favour the memory cells that can respond to that infection again. Antigen-inexperienced memory subsets, such as TIM and TVM cells, would be expected to eventually make way for the antigen-experienced memory cells, an inverse correlation that is consistent with published data44. Furthermore, the fact that the CD8+ T cells with the highest self-affinity are converted into TVM cells may even provide a way in which the organism can protect itself against autoimmunity, given that memory-phenotype T cells have decreased sensitivity to antigen and increased sensitivity to cytokines83. Thus, although questions remain regarding the development and function of antigen-inexperienced memory CD8+ T cells, they seem to be unquestionably useful to the organism. The data summarized in this article argue that the TIM–TVM cell paradigm will be useful as antigen-inexperienced memory T cells are further studied in both mice and humans.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank C. Suhr, S. Jameson and D. Hildeman for their helpful communications. This work was funded by US National Institutes of Health grants AI101205 and AI066121.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Jason T. White, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, The Peter Doherty Institute, University of Melbourne, 792 Elizabeth Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia

Eric W. Cross, Department of Immunology and Microbiology, University of Colorado Denver at Anschutz Medical Campus, School of Medicine, Mail Stop 8333, Room P18-8115, 12800 East 19th Avenue, Aurora, Colorado 80045-2537, USA

Ross M. Kedl, Department of Immunology and Microbiology, University of Colorado Denver at Anschutz Medical Campus, School of Medicine, Mail Stop 8333, Room P18-8115, 12800 East 19th Avenue, Aurora, Colorado 80045-2537, USA

References

- 1.Dobber R, Hertogh-Huijbregts A, Rozing J, Bottomly K, Nagelkerken L. The involvement of the intestinal microflora in the expansion of CD4+ T cells with a naive phenotype in the periphery. Dev Immunol. 1992;2:141–150. doi: 10.1155/1992/57057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Campion A, et al. Naive T cells proliferate strongly in neonatal mice in response to self-peptide/self-MHC complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4538–4543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062621699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haluszczak C, et al. The antigen-specific CD8+ T cell repertoire in unimmunized mice includes memory phenotype cells bearing markers of homeostatic expansion. J Exp Med. 2009;206:435–448. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldrath AW, Bevan MJ. Low-affinity ligands for the TCR drive proliferation of mature CD8+ T cells in lymphopenic hosts. Immunity. 1999;11:183–190. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80093-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldrath AW, Bogatzki LY, Bevan MJ. Naive T cells transiently acquire a memory-like phenotype during homeostasis-driven proliferation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:557–564. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieper WC, Jameson SC. Homeostatic expansion and phenotypic conversion of naive T cells in response to self peptide/MHC ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surh CD, Sprent J. Homeostatic T cell proliferation: how far can T cells be activated to self-ligands? J Exp Med. 2000;192:9–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho JH, et al. An intense form of homeostatic proliferation of naive CD8+ cells driven by IL-2. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1787–1801. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoklasek TA, Colpitts SL, Smilowitz HM, Lefrançois L. MHC class I and TCR avidity control the CD8 T cell response to IL-15/IL-15Rα complex. J Immunol. 2010;185:6857–6865. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandau MM, Winstead CJ, Jameson SC. IL-15 is required for sustained lymphopenia-driven proliferation and accumulation of CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:120–125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrançois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan JT, et al. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8732–8737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161126098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guimond M, et al. Interleukin 7 signaling in dendritic cells regulates the homeostatic proliferation and niche size of CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:149–157. doi: 10.1038/ni.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Napolitano LA, et al. Increased production of IL-7 accompanies HIV-1-mediated T-cell depletion: implications for T-cell homeostasis. Nat Med. 2001;7:73–79. doi: 10.1038/83381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fry TJ, et al. A potential role for interleukin-7 in T-cell homeostasis. Blood. 2001;97:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ernst B, Lee DS, Chang JM, Sprent J, Surh CD. The peptide ligands mediating positive selection in the thymus control T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation in the periphery. Immunity. 1999;11:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho JH, Kim HO, Surh CD, Sprent J. T cell receptor-dependent regulation of lipid rafts controls naive CD8+ T cell homeostasis. Immunity. 2010;32:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varshney P, Yadav V, Saini N. Lipid rafts in immune signalling: current progress and future perspective. Immunology. 2016;149:13–24. doi: 10.1111/imm.12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takada K, Jameson SC. Self-class I MHC molecules support survival of naive CD8 T cells, but depress their functional sensitivity through regulation of CD8 expression levels. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2253–2269. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldrath AW, Luckey CJ, Park R, Benoist C, Mathis D. The molecular program induced in T cells undergoing homeostatic proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16885–16890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyss L, et al. Affinity for self antigen selects Treg cells with distinct functional properties. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni.3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atherly LO, et al. The Tec family tyrosine kinases Itk and Rlk regulate the development of conventional CD8+ T Cells. Immunity. 2006;25:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berg LJ. Signalling through TEC kinases regulates conventional versus innate CD8+ T-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:479–485. doi: 10.1038/nri2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broussard C, et al. Altered development of CD8+ T cell lineages in mice deficient for the Tec kinases Itk and Rlk. Immunity. 2006;25:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horai R, et al. Requirements for selection of conventional and innate T lymphocyte lineages. Immunity. 2007;27:775–785. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weinreich MA, Odumade OA, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. T cells expressing the transcription factor PLZF regulate the development of memory-like CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:709–716. doi: 10.1038/ni.1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sosinowski T, et al. CD8α+ dendritic cell trans presentation of IL-15 to naive CD8+ T cells produces antigen-inexperienced T cells in the periphery with memory phenotype and function. J Immunol. 2013;190:1936–1947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White JT, et al. Virtual memory T cells develop and mediate bystander protective immunity in an IL-15-dependent manner. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11291. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee YJ, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Alternative memory in the CD8 T cell lineage. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jameson SC, Lee YJ, Hogquist KA. In: Advances in Immunology. Frederick WA, editor. Vol. 126. Academic Press; 2015. pp. 3–213. Ch. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Kaer L. Innate and virtual memory T cells in man. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:1916–1920. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spits H, Di Santo JP. The expanding family of innate lymphoid cells: regulators and effectors of immunity and tissue remodeling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spits H, Cupedo T. Innate lymphoid cells: emerging insights in development, lineage relationships, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:647–675. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheroutre H, Lambolez F, Mucida D. The light and dark sides of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:445–456. doi: 10.1038/nri3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiu Y, Peng K, Liu M, Xiao W, Yang H. CD8αα TCRαβ intraepithelial lymphocytes in the mouse gut. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1451–1460. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-4016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukuyama T, et al. Histone acetyltransferase CBP is vital to demarcate conventional and innate CD8+ T-cell development. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3894–3904. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01598-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verykokakis M, Boos MD, Bendelac A, Kee BL. SAP protein-dependent natural killer T-like cells regulate the development of CD8+ T cells with innate lymphocyte characteristics. Immunity. 2010;33:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee YJ, Holzapfel KL, Zhu J, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Steady-state production of IL-4 modulates immunity in mouse strains and is determined by lineage diversity of iNKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1146–1154. doi: 10.1038/ni.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinreich MA, et al. KLF2 transcription-factor deficiency in T cells results in unrestrained cytokine production and upregulation of bystander chemokine receptors. Immunity. 2009;31:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee YJ, et al. Tissue-specific distribution of iNKT cells impacts their cytokine response. Immunity. 2015;43:566–578. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koschella M, Voehringer D, Pircher H. CD40 ligation in vivo induces bystander proliferation of memory phenotype CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:4804–4811. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon JJ, et al. Naive CD4+ T cell frequency varies for different epitopes and predicts repertoire diversity and response magnitude. Immunity. 2007;27:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akue AD, Lee JY, Jameson SC. Derivation and maintenance of virtual memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:2516–2523. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JY, Hamilton SE, Akue AD, Hogquist KA, Jameson SC. Virtual memory CD8 T cells display unique functional properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13498–13503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307572110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tripathi P, et al. IL-4 and IL-15 promotion of virtual memory CD8+ T cells is determined by genetic background. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:2333–2339. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Renkema KR, et al. IL-4 sensitivity shapes the peripheral CD8+ T cell pool and response to infection. J Exp Med. 2016;213:1319–1329. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fulton RB, et al. The TCR’s sensitivity to self peptide- MHC dictates the ability of naive CD8+ T cells to respond to foreign antigens. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:107–117. doi: 10.1038/ni.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurzweil V, LaRoche A, Oliver PM. Increased peripheral IL-4 leads to an expanded virtual memory CD8+ population. J Immunol. 2014;192:5643–5651. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martinet V, et al. Type I interferons regulate eomesodermin expression and the development of unconventional memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7089. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ventre E, et al. Negative regulation of NKG2D expression by IL-4 in memory CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2012;189:3480–3489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morris SC, et al. Endogenously produced IL-4 nonredundantly stimulates CD8+ T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2009;182:1429–1438. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boyman O, Kovar M, Rubinstein MP, Surh CD, Sprent J. Selective stimulation of T cell subsets with antibody–cytokine immune complexes. Science. 2006;311:1924–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1122927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carlson CM, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 2006;442:299–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takada K, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 is required for trafficking but not quiescence in postactivated T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:775–783. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ku CC, Murakami M, Sakamoto A, Kappler J, Marrack P. Control of homeostasis of CD8+ memory T cells by opposing cytokines. Science. 2000;288:675–678. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chu T, et al. Bystander-activated memory CD8 T cells control early pathogen load in an innate-like, NKG2D-dependent manner. Cell Rep. 2013;3:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rudd BD, et al. Nonrandom attrition of the naive CD8+ T-cell pool with aging governed by T-cell receptor:pMHC interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13694–13699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107594108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Correia MP, et al. Hepatocytes and IL-15: a favorable microenvironment for T cell survival and CD8+ T cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2009;182:6149–6159. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doherty DG. Immunity, tolerance and autoimmunity in the liver: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2016;66:60–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jenne CN, Kubes P. Immune surveillance by the liver. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:996–1006. doi: 10.1038/ni.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Crispe IN. Liver antigen-presenting cells. J Hepatol. 2011;54:357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knolle P, et al. Human Kupffer cells secrete IL-10 in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge. J Hepatol. 1995;22:226–229. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang M, Xu S, Han Y, Cao X. Apoptotic cells attenuate fulminant hepatitis by priming Kupffer cells to produce interleukin-10 through membrane-bound TGF-β. Hepatology. 2011;53:306–316. doi: 10.1002/hep.24029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee WY, et al. An intravascular immune response to Borrelia burgdorferi involves Kupffer cells and iNKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:295–302. doi: 10.1038/ni.1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Spellberg B, Edwards JE. Type 1/type 2 immunity in infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:76–102. doi: 10.1086/317537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Byrne JA, Stankovic AK, Cooper MD. A novel subpopulation of primed T cells in the human fetus. J Immunol. 1994;152:3098–3106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Min HS, et al. MHC class II-restricted interaction between thymocytes plays an essential role in the production of innate CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2011;186:5749–5757. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee YJ, et al. Generation of PLZF+ CD4+ T cells via MHC class II–dependent thymocyte–thymocyte interaction is a physiological process in humans. J Exp Med. 2010;207:237–246. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacomet F, et al. Evidence for eomesodermin-expressing innate-like CD8+ KIR/NKG2A+ T cells in human adults and cord blood samples. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:1926–1933. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Azzam HS, et al. Fine tuning of TCR signaling by CD5. J Immunol. 2001;166:5464–5472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Azzam HS, et al. CD5 expression is developmentally regulated by T cell receptor (TCR) signals and TCR avidity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2301–2311. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Herndler-Brandstetter D, et al. Post-thymic regulation of CD5 levels in human memory T cells is inversely associated with the strength of responsiveness to interleukin-15. Hum Immunol. 2011;72:627–631. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Proliferation and differentiation potential of human CD8+ memory T-cell subsets in response to antigen or homeostatic cytokines. Blood. 2003;101:4260–4266. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Larbi A, Fulop T. From “truly naive” to “exhausted senescent” T cells: when markers predict functionality. Cytometry A. 2014;85:25–35. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moran AE, et al. T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1279–1289. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Intlekofer AM, et al. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Romero P, et al. Four functionally distinct populations of human effector-memory CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2007;178:4112–4119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Su LF, Kidd BA, Han A, Kotzin JJ, Davis MM. Virus-specific CD4+ memory-phenotype T cells are abundant in unexposed adults. Immunity. 2013;38:373–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Marusina AI, et al. CD4+ virtual memory: antigen-inexperienced T cells reside in the naive, regulatory, and memory T cell compartments at similar frequencies, implications for autoimmunity. J Autoimmun. 2017;77:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schüler T, Hämmerling GJ, Arnold B. Cutting edge: IL-7-dependent homeostatic proliferation of CD8+ T cells in neonatal mice allows the generation of long-lived natural memory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:15–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lynch HE, et al. Thymic involution and immune reconstitution. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schwab R, et al. Expanded CD4+ and CD8+ T cell clones in elderly humans. J Immunol. 1997;158:4493–4499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mehlhop-Williams ER, Bevan MJ. Memory CD8+ T cells exhibit increased antigen threshold requirements for recall proliferation. J Exp Med. 2014;211:345–356. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Else KJ, Finkelman FD, Maliszewski CR, Grencis RK. Cytokine-mediated regulation of chronic intestinal helminth infection. J Exp Med. 1994;179:347–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hamann D, et al. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1407–1418. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]