Abstract

Thrombocytopenia is an important cause of hemorrhage and death after radiation injury, but the pathogenesis of radiation-induced thrombocytopenia has not been fully characterized. Here, we investigated the influence of radiation-induced endothelial cell injury on platelet regeneration. We found that human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) underwent a high rate of apoptosis, accompanied by a significant reduction in the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) at 96 h after radiation. Subsequent investigations revealed that radiation injury lowered the ability of HUVECs to attract migrating megakaryocytes (MKs). Moreover, the adhesion of MKs to HUVECs was markedly reduced when HUVECs were exposed to radiation, accompanied by a decreased production of platelets by MKs. In vivo study showed that VEGF treatment significantly promoted the migration of MKs into the vascular niche and accelerated platelet recovery in irradiated mice. Our studies demonstrate that endothelial cell injury contributes to the slow recovery of platelets after radiation, which provides a deeper insight into the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia induced by radiation.

Keywords: radiation, endothelial cell, megakaryocyte, platelet, VEGF

INTRODUCTION

Platelets, vital regulators in hemorrhage, infection, thrombosis and inflammation [1], are derived from megakaryocytes (MKs) through a multistage process, in which hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), megakaryocyte progenitors (MKPs), mature MKs, and terminal differentiation of MKs are involved [2]. In the terminal process of maturation, MKs extrude proplatelets, extend into the sinusoidal vasculature, and release platelets into the peripheral blood [3]. When mature MKs move from the ‘endosteal niche’ to the ‘vascular niche’, the interaction between endothelial cells and MKs is indispensable in the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment [3, 4].

Previous studies have reported that radiation can cause great damage to hematopoietic system components, which leads to the reduction of platelets, and subsequently life-threatening thrombocytopenia [5, 6]. HSC transplantation is an effective measure for treating thrombocytopenia; however, patients who receive total body irradiation (TBI) and undergo HSC transplantation require a longer period in which to recover platelets than healthy individuals do [7–9], which suggests that in addition to stem cells, there are other factors in the BM microenvironment affecting the reconstruction of hematopoietic function in those suffering from radiation injury. However, their precise mechanism has not been fully characterized.

BM endothelial cells are a crucial component of the stroma in hematopoietic regulation [10], which produces numerous soluble factors that promote the differentiation and regeneration of the HSCs in vitro after radiation exposure [11, 12]. Deletion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)R2 in adult mice or systemic delivery of anti-VE-cadherin-specific antibody could delay hematologic recovery following radiation injury [13, 14]. Disruption of the BM vascular niche by interfering with VE-cadherin impairs MK maturation and polyploidization [15]. However, it remains to be determined whether abnormalities of endothelial cells can affect platelet regeneration in the process of hematopoietic reconstitution after radiation injury.

In this paper, we found that along with the radiation-induced damage of endothelial cells, the expression of VEGF was decreased at 96 h post irradiation. Additionally, the adhesion and migration of MKs to HUVECs were weakened, thus resulting in reduced platelet production. Supplementing VEGF through intravenous injection enabled us to rescue platelet numbers in mice that had received radiation. This work focused on the role of the BM microenvironment in thrombopoiesis to further understanding of the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia induced by radiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

HUVECs were purchased from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS, Shanghai) and cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (Gibco, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum. CD34+ cells and human primary MKs were obtained from human umbilical cord blood using immunomagnetic beads (Stem Cell Technologies, Canada) as previously described [16]. The CD34+ cells were then seeded in 24-well plates with a density of 4 × 104/well, and were further cultured in serum-free medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Canada) containing 20 ng/ml recombinant human thrombopoietin (rhTPO) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The use of human umbilical cord blood was approved by the Human Medical Ethics Committee of the Third Military Medical University.

Mice and irradiation

Male BALB/c mice (56–70 days old) were purchased from the Institute of Zoology (Beijing, China), and the animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Third Military Medical University. Mice and HUVECs were irradiated using an RS-2000 Biological System (X-ray source, USA) at a constant rate of 1.284 Gy/min, for 234 s, thus receiving a single dose of 5 Gy X-ray.

Scanning electron microscope

A total of 3 × 104/ml HUVECs (500 μl) were seeded into a 24-well plate containing glass slides, which were irradiated after a 6 h-long adherence. At 96 h post irradiation, HUVECs were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. Images were captured using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) instrument (HITACHI, Japan).

Cell apoptosis detection

A total of 1 × 105/ml HUVECs were cultured in a 6-well plate, and were then collected at 96 h post irradiation. Cell apoptosis was detected using an Annexin V-FITC kit (Dojindo, Japan).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

HUVECs RNA was extracted using RNAiso plus Reagent (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the instructions. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a promega reverse transcription kit. The primers were synthesized as follows: VEGF, 5'-CGGTATAAGTCCTGGAGCGTTC-3' (F), 5'-GCCTCGGCTTGTCACATCTG-3' (R); GAPDH, 5'-TGAGTATGTGGTGGAGTCTAC-3' (F), 5'-TGGACTGTGGTCATGAGCC-3' (R). The data were collected from an IQTM5 real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) Detection system (Bio-Rad, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

HUVECs (5 × 104/ml, 2 ml) were cultured in a 6-well plate and exposed to 5 Gy radiation. Cell supernatants were obtained at 96 h post irradiation and analyzed by a human VEGF enzyme–linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Neobioscience, China).

Western blot assay

HUVECs were harvested at 96 h post irradiation. A total of 40 μg cell protein was separated by a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, which was then transferred onto a PVDF membrane and probed with an anti-VEGF antibody (1:500, NOVUS, USA). GAPDH was employed as an internal standard, and the Pierce ECL Plus reagent (1:1000, Thermo, USA) was used to display the protein bands. Images were acquired by Molecular Imager ChemiDocTM XRS+ with Image Lab TM software (Bio-Rad, USA).

Migration assay

To assess the migration of MKs, we used a Millipore transwell (8 μm pore size). MKs were purified from CD34+ cells and cultured in serum-free medium with 20 ng/ml rhTPO for 11 days. HUVECs (2 × 104/ml) were seeded into a 24-well plate and received 5 Gy radiation. MKs (1 × 106/ml, 100 μl) were added to the transwell chamber at the 96th hour post irradiation of HUVECs; the bottom chamber contained medium with 20 ng/ml VEGF (Peprotech, USA) or HUVEC monolayers. After a 5 h-long incubation, MKs migrated onto the chamber membrane. The cells were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for visualization.

Adhesion assay

The adhesion assay was performed according to previous reports [17]. MKs derived from CD34+ cells were cultured for 11 days and pre-incubated with 2’,7’-bis-(2-carboxyethyl)-5-(-and-6)-carboxyfluorescein, acetoxymethyl ester (BCECF AM, Beyotime, China) for 1 h at 37°C. BCECF-labeled MKs (3.5 × 105/ml) were washed with PBS and resuspended with the medium. They were then co-incubated with the injured HUVEC monolayers for 5 h. The cells were further washed slightly, and the fluorescence intensity was detected using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (MD, USA) at 488 nm and 535 nm.

Analysis of culture-derived platelets

The platelet production experiment was adapted from Dhanjal et al. [18]. HUVECs (5 × 104/ml, 2 ml) were seeded on a Millipore transwell microporous membrane (5 μm pore size) and received 5 Gy radiation. The transwell inserts with the HUVEC monolayers were placed in a 6-well plate. MKs derived from CD34+ cells were cultured for 13 days in the presence of 20 ng/ml rhTPO. After 48 h, MKs (2 × 106/ml) and VEGF (20 ng/ml) were added and co-incubated with injured HUVEC monolayers in the upper chamber; 1 ml medium was placed in the lower plate. The plate was incubated for another 48 h at 37°C. Platelet assays were performed as we have previously described [16]. The suspension in the lower chamber was centrifugated and platelets were stained with FITC-CD41, APC-CD42b antibodies (Biolegend, USA) and 10 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI). Conjugated pellets were washed and counted by flow cytometer (FACS CantoII flow cytometer, BD, USA).

Platelet recovery experiments

Groups of 10 male BALB/c mice were injected intravenously with the recombinant murine VEGF (4 μg/kg, Peprotech, USA) or saline daily for 7 consecutive days. The tail vein blood was collected and counted by hemocytometer (XT- 2000iV, Sysmex, Japan).

Histology analysis

The thighbones of mice were obtained at 14 days post irradiation and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde. Samples were decalcified in EDTA for 10 days, and were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Images were acquired using an Olympus microscope.

Statistical analysis

Experiments in this study were performed at least three times. The data were analyzed by PASW statistical software and expressed as mean ± S.D. Two-tailed Student's t-tests were used to test the differences between two groups, and comparisons between more than two groups were performed with one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

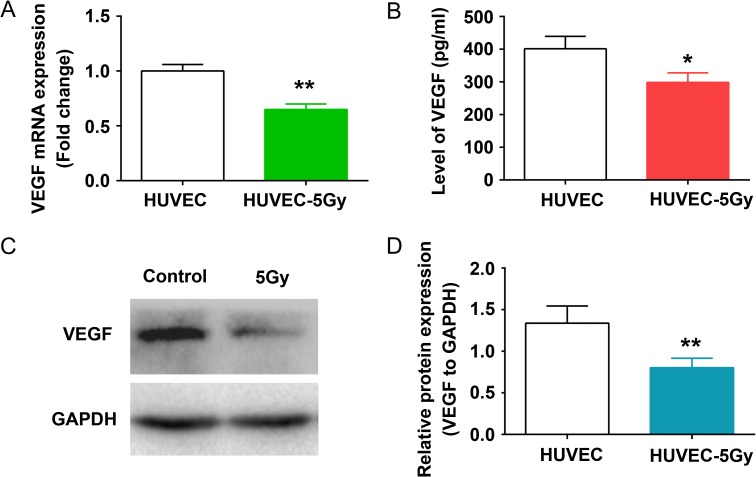

Radiation induced the morphologic alteration and apoptosis of endothelial cells

HUVECs are widely used in studies focusing on the role of endothelial cells in hematopoietic regulation [12, 19]. To evaluate the effect of radiation on vascular endothelium, we employed HUVECs and first observed the morphological alteration of irradiated cells. The morphology of irradiated HUVECs was found markedly changed relative to that of untreated cells, manifested as cytoplasmic blebbing (Fig. 1A) and a larger surface area (Fig. 1B). Moreover, we analyzed cell apoptosis using a flow cytometer. The apoptosis rate of irradiated HUVECs was revealed to be ~40%, which was four-fold higher than that of the control group (Fig. 1C and D), further demonstrating that 5 Gy radiation is detrimental to the vascular endothelium.

Fig. 1.

Radiation induced the morphologic alteration and apoptosis in HUVECs. HUVEC monolayers were exposed to 5 Gy radiation and incubated at 37°C for 96 h. (A) Changes in HUVEC morphology were detected by phase contrast imaging. (B) HUVEC morphology alterations were observed with SEM. (C) Apoptosis in irradiated HUVECs was analyzed by the Annexin V, FITC kit. (D) Histogram showing the mean apoptosis rate for each group. **P < 0.01 vs HUVEC.

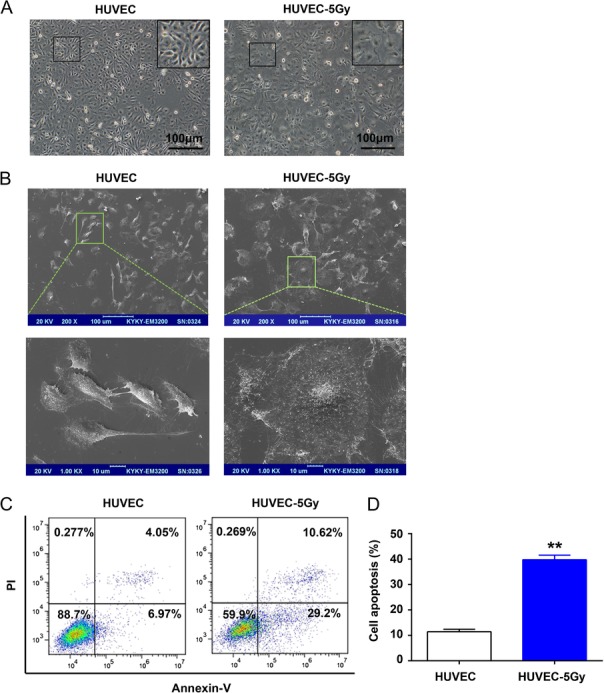

Radiation decreased the expression of VEGF in HUVECs

Numerous secreted protein or paracrine factors produced by BM endothelial cells were dynamically changed after radiation [20]. VEGF is an angiogenic cytokine expressed in vascularized tissues, which is capable of promoting the proliferation and survival of endothelial cells [21]. As HUVECs were injured by 5 Gy radiation, we further focused on VEGF by first conducting a quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). We found that the mRNA expression of VEGF was increased at 24 h and 48 h after 5 Gy radiation, but was significantly reduced at 96 h post irradiation, compared with that of non-irradiated cells (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. 1). ELISA indicated that the amount of released VEGF in irradiated HUVECs was decreased compared with in the control cells (Fig. 2B). Moreover, western blot clearly demonstrated that the expression of VEGF in irradiated HUVECs was decreased at 96 h post irradiation (Fig. 2C and D).

Fig. 2.

Decreased expression and secretion of VEGF in HUVECs after radiation. HUVEC monolayers were irradiated with 5 Gy radiation and incubated at 37°C for 96 h. (A) The mRNA levels of VEGF were analyzed by qRT-PCR. **P < 0.01 vs HUVEC. (B) VEGF secretion was quantified by ELISA at 96 h after 5 Gy radiation. *P < 0.05 vs HUVEC. (C) The expression of VEGF in HUVEC lysates were determined by western blot, and anti-GAPDH was used as an internal standard. (D) Relative protein expression for each group was analyzed by Image J software. **P < 0.01 vs HUVEC.

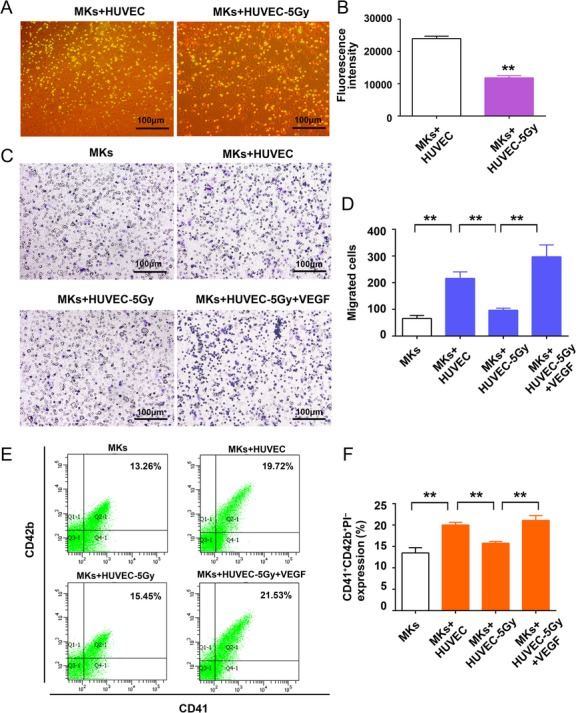

Radiation-induced HUVEC injury weakened the adhesion, migration, and platelet production of MKs

The adhesion of MKs to BM stroma cells is an important process in hematopoiesis. Thus, we subsequently performed an adhesion assay in which HUVECs were employed. MKs stained by BCECF-AM emerged as green fluorescent cells upon excitation (Fig. 3A). The fluorescence intensity of MKs that adhered to irradiated HUVECs was dramatically less than that of untreated cells (Fig. 3B), which suggest that BM stroma injury caused by radiation harms MK adhesion. Due to the fact that morphological changes indicate an influence on the migratory ability of cells [22], we evaluated the effect of irradiated HUVECs on MK migration using a transwell system. We first found that VEGF has a strong ability to attract MKs migration (Supplementary Fig. 2). Notably, radiation-induced HUVEC injury could markedly decrease the number of MKs migrating toward HUVECs, while VEGF supplement could rescue the rates of MK migration (Fig. 3C and D). A previous study pointed out that cytokines (such as VEGF) secreted from vascular endothelial cells can affect MK maturation and the following platelet release [23]. Using flow cytometry, we analyzed the content of platelets (CD41+CD42b+PI-) released from matured MKs in the absence and presence of endothelial cells. The results showed that co-culturing MKs with HUVECs promoted platelet production, while radiation-induced endothelial injury significantly attenuated this effect (Fig. 3E and F). Similarly, addition of VEGF could evidently promote the platelet production of MKs alone or with radiation-injured HUVECs (Fig. 3F and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 3.

Radiation-induced HUVEC injury weakened the adhesion, migration, and platelet production of MKs. (A) The adhesion of MKs was photographed by phase contrast imaging. (B) The mean fluorescence intensity of adherent MKs was examined using an M2 microplate reader. **P < 0.01 vs MKs + HUVEC. (C) MKs that migrated through transwell were stained with crystal violet and examined under a microscope. (D) The average number of migrated cells from four random fields were counted for each group. **P < 0.01 MKs vs MKs + HUVEC, **P < 0.01 MKs+HUVEC vs MKs + HUVEC-5 Gy, **P < 0.01 MKs+HUVEC-5 Gy vs MKs + HUVEC-5 Gy + VEGF. (E) CD34+ cells were cultured for 13 days and co-cultured with irradiated HUVEC monolayers. The platelets were stained with APC-CD42b, FITC-CD41 and PI and were detected by flow cytometer. (F) The expression of platelets derived from MKs in each group. **P < 0.01 MKs vs MKs + HUVEC, **P < 0.01 MKs vs MKs + HUVEC, **P < 0.01 MKs + HUVEC vs MKs + HUVEC-5 Gy, **P < 0.01 MKs + HUVEC-5 Gy vs MKs + HUVEC-5 Gy + VEGF.

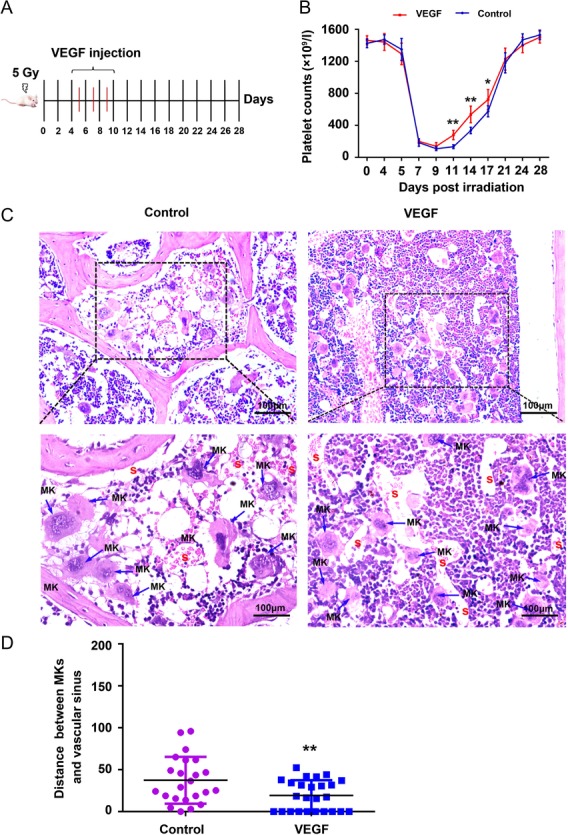

VEGF promotes platelet recovery in mice with thrombocytopenia induced by radiation

To evaluate the therapeutic effect of exogenous VEGF on thrombocytopenia induced by radiation, we intravenously injected VEGF into BALB/c mice at Day 4 post–5 Gy TBI for 7 successive days (Fig. 4A). The number of platelets in irradiated mice presented a trend of fluctuation, which can be generalized as a sharp decrease and an increasing recovery (Fig. 4 B). The declining platelet level reached the nadir on the ninth day. Notably, the platelet counts of mice treated with VEGF began to recover on the 11th day, 3 days ahead of the saline group (Fig. 4B). H&E staining showed that there was a paucity of hematopoietic cells in saline-treated mice on the 14th day (Fig. 4C), and the distance between MKs and the vascular sinus niche was much longer than that in the VEGF group (Fig. 4C and D). These data suggest that VEGF promotes the migration of MKs to the vascular sinus and accelerates platelet recovery in mice with thrombocytopenia induced by radiation.

Fig. 4.

VEGF administration enhanced platelet recovery in mice with thrombocytopenia. (A) Groups of 10 male BALB/c mice were injected intravenously with VEGF at Day 4 post–5 Gy TBI for 7 successive days. (B) Changes in the platelets counts in tail vein blood of mice in each group. **P < 0.01 vs Control, *P < 0.05 vs Control. (C) H&E stain of bone marrow in the mice. MK: megakaryocyte S: vascular sinusoid. (D) A quantification of the distance between MKs and vascular sinus of different groups was compared. **P < 0.01 vs Control.

DISCUSSION

Thrombocytopenia caused by radiation is the main cause of hemorrhage, infection, and even death for patients with radiation injury [24]. In this study, we showed that radiation-induced endothelial cell injury weakened the migration and adhesion of MKs to HUVECs, which hindered platelet regeneration in the process of hematopoietic reconstitution. Our research revealed the reason for slow platelet recovery after radiation injury from the perspective of the hematopoietic microenvironment.

The BM hematopoietic microenvironment consists of the endosteal niche and the vascular niche, which provides for the maintenance, self-renewal and differentiation of HSCs [25]. Endothelial cells are an important cell type within the vascular niche, which play a crucial role in the regulation of hematopoiesis, especially megakaryocytopoiesis [26]. BM is sensitive to radiation. In addition to the direct damage to hematopoietic cells [27], radiation can also influence the structure and function of endothelial cells. Our results showed that radiation caused HUVEC apoptosis and morphological alteration, which was consistent with the results of a prior study [22]. Many studies have demonstrated that radiation altered the expression of numerous autocrine and paracrine factors in BM endothelial cells, including GM-CSF, VCAM-1, CXCL12, HGF and PECAM [10, 20, 28]. VEGF is a critical cytokine regulating the interactions between MKs and endothelial cells [15, 29]. Therefore, we focused on the expression and secretion of VEGF in HUVECs. We found that the mRNA expression of VEGF was increased at 24 h and 48 h after 5 Gy radiation (Supplementary Fig. 1), but was significantly decreased at 96 h post irradiation. The early increase in VEGF may be the stress response of endothelial cells to radiation [30, 31], while the late decrease in VEGF is probably due to the apoptosis of endothelial cells induced by radiation. Actually, 96 h also represents a time-point for early hematopoietic cell recovery in the BM of irradiated mice [32]. We chose a 5-Gy dose since this causes obvious damage to the BM vascular niche, but is still sublethal [20]. These results suggest that endothelial cells and their secreted soluble factors, such as VEGF, partially contributed to the changes in the BM microenvironment following radiation injury.

The vascular niche is a site of MK terminal maturation and thrombopoiesis [3]. The conditions in the vascular endothelium are intimately associated with the terminal differentiation of MKs [33]. VEGF is identified as a vital cytokine regulating proliferation and survival of endothelial cells, which evidently promote the differentiation and maturation of MKs and localization to the vascular niche [23, 29, 34]. As such, we speculated that alterations in the BM microenvironment, including morphological and VEGF changes, can affect the behavior of MKs. In this study, we observed that radiation-induced HUVEC injury lowered the adhesion of MKs, and weakened the ability of HUVECs to attract MKs, thereby decreasing the production of platelets derived from MKs. We also demonstrated that the supplement of exogenous VEGF significantly promoted migration and platelet production of MKs when co-cultured with HUVECs injured from radiation in vitro. Moreover, VEGF administration led to a faster movement of MKs toward the vascular niche and a rapid recovery of the platelet level in a radiation-induced thrombocytopenia mouse model. These findings suggest that radiation-induced reduction and slow recovery of platelets is associated with injury associated with irradiated endothelial cells, which may provide a new avenue for the treatment of radiation-induced thrombocytopenia.

Taken together, the data presented here demonstrated that radiation-induced endothelial cell injury contributed to the delayed recovery of platelet numbers (by influencing the adhesion and migration of MKs) as well as of platelet release, thereby providing a new insight into the pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia induced by radiation.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at the Journal of Radiation Research online.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Fund of China (81602790, 81573084), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2014T70976), the Chongqing Postdoctoral Science Foundation (XM201339), the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (CSTC2013JCYJA10119) and the Technological Innovation Leader of Chongqing (CSTCKJCXLJRC06).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

F.C. and M.S. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript with the assistance of D.Z., S.W., S.C., C.W., Y.T., M.H. and M.C.; Y. S. and Y.X. contributed to the initial experimental design; J.W. designed and revised the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Semple JW, Italiano JE Jr, Freedman J. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol 2011;11:264–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen S, Su Y, Wang J, et al. ROS-mediated platelet generation: a microenvironment-dependent manner for megakaryocyte proliferation, differentiation, and maturation. Cell Death Dis 2013;4:e722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Niswander LM, Fegan KH, Kingsley PD, et al. SDF-1 dynamically mediates megakaryocyte niche occupancy and thrombopoiesis at steady state and following radiation injury. Blood 2014;124:277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel SR, Hartwig JH, Italiano JE Jr. The biogenesis of platelets from megakaryocyte proplatelets. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3348–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stasi R. How to approach thrombocytopenia. Hematology Am Soc of Hematol Educ Program 2012;2012:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dainiak N. Hematologic consequences of exposure to ionizing radiation. Exp Hematol 2002;30:513–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bruno B, Gooley T, Sullivan KM, et al. Secondary failure of platelet recovery after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2001;7:154–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kanamaru S, Kawano Y, Watanabe T, et al. Low numbers of megakaryocyte progenitors in grafts of cord blood cells may result in delayed platelet recovery after cord blood cell transplant. Stem Cells 2000;18:190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen TW, Hwang SM, Chu IM, et al. Characterization and transplantation of induced megakaryocytes from hematopoietic stem cells for rapid platelet recovery by a two-step serum-free procedure. Exp Hematol 2009;37:1330–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaugler MH, Squiban C, Claraz M, et al. Characterization of the response of human bone marrow endothelial cells to in vitro irradiation. Br J Haematol 1998;103:980–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Muramoto GG, Chen B, Cui X, et al. Vascular endothelial cells produce soluble factors that mediate the recovery of human hematopoietic stem cells after radiation injury. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2006;12:530–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rafii S, Shapiro F, Pettengell R, et al. Human bone marrow microvascular endothelial cells support long-term proliferation and differentiation of myeloid and megakaryocytic progenitors. Blood 1995;86:3353–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hooper AT, Butler JM, Nolan DJ, et al. Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell 2009;4:263–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salter AB, Meadows SK, Muramoto GG, et al. Endothelial progenitor cell infusion induces hematopoietic stem cell reconstitution in vivo. Blood 2009;113:2104–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Avecilla ST, Hattori K, Heissig B, et al. Chemokine-mediated interaction of hematopoietic progenitors with the bone marrow vascular niche is required for thrombopoiesis. Nat Med 2004;10:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu Y, Wang S, Shen M, et al. hGH promotes megakaryocyte differentiation and exerts a complementary effect with c-Mpl ligands on thrombopoiesis. Blood 2014;123:2250–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen S, Du C, Shen M, et al. Sympathetic stimulation facilitates thrombopoiesis by promoting megakaryocyte adhesion, migration, and proplatelet formation. Blood 2016;127:1024–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dhanjal TS, Pendaries C, Ross EA, et al. A novel role for PECAM-1 in megakaryocytokinesis and recovery of platelet counts in thrombocytopenic mice. Blood 2007;109:4237–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bal G, Kamhieh-Milz J, Futschik M, et al. Transcriptional profiling of the hematopoietic support of interleukin-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Cell Transplant 2012;21:251–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Himburg HA, Sasine J, Yan X, et al. A molecular profile of the endothelial cell response to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res 2016;186:141–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Du P, Dai F, Chang Y, et al. Role of miR-199b-5p in regulating angiogenesis in mouse myocardial microvascular endothelial cells through HSF1/VEGF pathway. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2016;47:142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Feys L, Descamps B, Vanhove C, et al. Radiation-induced lung damage promotes breast cancer lung-metastasis through CXCR4 signaling. Oncotarget 2015;6:26615–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gars E, Rafii S. It takes 2 to thrombopoies in the vascular niche. Blood 2012;120:2775–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waselenko JK, MacVittie TJ, Blakely WF, et al. Medical management of the acute radiation syndrome: recommendations of the Strategic National Stockpile Radiation Working Group. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:1037–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony–forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells 1978;4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cao H, Oteiza A, Nilsson SK. Understanding the role of the microenvironment during definitive hemopoietic development. Exp Hematol 2013;41:761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wen S, Dooner M, Cheng Y, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell–derived extracellular vesicles rescue radiation damage to murine marrow hematopoietic cells. Leukemia 2016;30:2221–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mazo IB, Quackenbush EJ, Lowe JB, et al. Total body irradiation causes profound changes in endothelial traffic molecules for hematopoietic progenitor cell recruitment to bone marrow. Blood 2002;99:4182–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mohle R, Green D, Moore MA, et al. Constitutive production and thrombin-induced release of vascular endothelial growth factor by human megakaryocytes and platelets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:663–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Adachi N, Kubota Y, Kosaka K, et al. Low-dose radiation pretreatment improves survival of human ceiling culture–derived proliferative adipocytes (ccdPAs) under hypoxia via HIF-1 alpha and MMP-2 induction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015;463:1176–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nambiar DK, Rajamani P, Singh RP. Silibinin attenuates ionizing radiation–induced pro-angiogenic response and EMT in prostate cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015;456:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yamazaki K, Allen TD. Ultrastructural and morphometric alterations in bone marrow stromal tissue after 7 Gy irradiation. Blood Cells 1991;17:527–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Forconi S, Gori T. Endothelium and hemorheology. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2013;53:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pitchford SC, Lodie T, Rankin SM. VEGFR1 stimulates a CXCR4-dependent translocation of megakaryocytes to the vascular niche, enhancing platelet production in mice. Blood 2012;120:2787–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.