Abstract

The molecular understanding of cellular processes requires the identification and characterization of the involved protein complexes. Affinity-purification and mass spectrometric analysis (AP–MS) are performed on a routine basis to detect proteins assembled in complexes. In particular, protein abundances obtained by quantitative mass spectrometry and direct protein contacts detected by crosslinking and mass spectrometry (XL–MS) provide complementary datasets for revealing the composition, topology and interactions of modules in a protein network. Here, we aim to combine quantitative and connectivity information by a webserver tool in order to infer protein complexes. In a first step, modeling protein abundances and functional annotations from Gene Ontology (GO) results in a network which, in a second step, is integrated with connectivity data from XL–MS analysis in order to complement and validate the protein complexes in the network. The output of our integrative approach is a quantitative protein interaction map which is supplemented with topological information of the detected protein complexes. compleXView is built up by two independent modules which are dedicated to the analysis of label-free AP–MS data and to the visualization of the detected complexes in a network together with crosslink-derived distance restraints. compleXView is available to all users without login requirements at http://xvis.genzentrum.lmu.de/compleXView.

INTRODUCTION

Proteins interact and build up complexes in order to execute their function rather than acting as individual proteins. The assembly of complexes is a dynamic and highly regulated process which ensures that the protein function is exerted at the proper cellular localization and time. Thus, elucidating the molecular mechanisms of cellular processes requires the biochemical analysis of the involved proteins and their interactions in a signaling pathway.

Affinity purification coupled to mass spectrometry (AP–MS) is a widely used technique to detect protein interactions in biological samples. The identified interactors of a certain bait protein are called preys and their abundances are obtained from the respective peptide intensities by mass spectrometry. In addition, recent efforts have combined chemical crosslinking and mass spectrometry (XL–MS) for the identification of proteins which directly contact each other or are in close proximity within a complex and thus, crosslinks provide topological information. In most cases, XL–MS studies apply amine reactive crosslinking agents to covalently link lysine residues and dedicated software to identify the crosslinked lysines from fragment ion spectra (1, 2).

Affinity-purifications of protein complexes are usually contaminated with unspecific proteins depending on the purification protocol, affinity-tag or cell line. To separate contaminants from interacting proteins is crucial for determining the protein complex composition. Negative control samples are used together with statistical methods to filter out spurious interactions. A frequently used method is SAINT (significance analysis of interactome) (3), which models the abundances of protein identifications in the negative and positive samples into a mixture probability distribution that calculates the odds of an interaction being true rather than false. Additional software programs like MiST (mass spectrometry interaction statistics) (4) and compPASS (comparative proteomic analysis software suite) (5), measure the abundance, reproducibility and specificity of the identification, and combine those into a probability score of interaction. In all three methods, scores above certain thresholds indicate the prey as an interactor of the bait and represent the bait–prey interactions in a table depicting the abundance values of the preys.

There are two different approaches for modeling network topology in the population of interactions: the Spoke model and the Matrix model (6). The Spoke model displays a network as a wheel-like arrangement of baits connected to multiple preys through spokes lacking connectivity between proteins. Thus, no higher-order structures and very few protein clusters are observed in this kind of network. In contrast, in the Matrix model the input data is first transformed in order to infer interactions between preys, which results in a network with higher-order structures and protein clusters. However, the number of false interactions is proportionally amplified to the size of the dataset.

Approaches for inferring prey–prey interactions include profile correlation, socio-affinity index (7) and hypergeometric probabilities (8). The profile correlation method assumes that protein complexes are regulated and perturbed as a single entity where changes in subunit abundances will change others accordingly. Thus, high correlation in the co-variation of abundances across the different purifications is expected. In the second method, the socio-affinity index measures the number of times two proteins appear in the same purification relative to their frequency in the whole dataset. Other methods rely on machine learning algorithms and require large datasets, bona-fide complexes for training, and the derivation of loose explanatory variables based on measures of abundance, co-purification, and reproducibility (9).

The majority of protein interaction studies includes less than a few tens of baits turning abundance profile correlations into the most appropriate method for the identification of prey–prey interactions as other approaches are tailored to cope with hundreds of baits (7–9).

Subsequent to calculating a measure of interaction strength, proteins are displayed in a network and clustered by different algorithms in order to infer protein complexes and submodules. Clustering algorithms either use properties inherent to the network or introduce prior knowledge into their models. Algorithms such as force-layout, Markov Clustering (MCL) (10) and Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) (11) belong to the first category and apply the calculated interaction strengths and local connectivity within the network to group proteins into clusters. Algorithms such as CORE (12) and WCOACH (13) belong to the second category, which either adhere to the protein-complex-organization model (7) or use Gene Ontology (GO) functional annotations to weight the membership of a protein in a cluster.

Here, we introduce compleXView a webserver that calculates measures of abundance, reproducibility and specificity derived from AP–MS experiments to discriminate true from false bait–prey interactions. Prey–prey interactions are predicted and quantified based on the profile correlation method and these values together with GO functional similarities are supplied to an MCL algorithm. The webserver integrates crosslink data to complement and validate the predicted interactions and to provide connectivity information within and between complexes in a network. compleXView is an extension of the previously described xVis webserver (14) and facilitates the generation of protein interaction tables at every step and visualizes the network of protein complexes as interactive maps.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Datasets

Two datasets from previous studies were analyzed, each include label-free quantification of protein abundances and the identification of chemical crosslinks by mass spectrometric analyses.

The first dataset (15) comprises affinity-purifications of 14 different bait proteins of the protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) network, including: PP2A catalytic subunit alpha (PP2AA), PP2A catalytic subunit beta (PP2AB), PP2A regulatory subunit A beta (2AAB), PP2A regulatory subunit B alpha (2ABA), PP2A regulatory subunit B gamma (2ABG), PP2A regulatory subunit delta (2A5D), PP2A regulatory subunit epsilon (2A5E), PP2A regulatory subunit gamma (2A5G), protein phosphatase 4 catalytic subunit (PP4C), Immunoglobulin-binding protein 1 (IGBP1), Shugoshin-like 1 (SGOL1), CTTNBP2 N-terminal-like protein (CT2NL), Striatin-interacting protein 2 (FA40B or STRP2) and FGFR1 oncogene partner (FR1OP).

The second dataset (16) includes five bait proteins of distinct complexes which are associated with DNA including: ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase 1 (PRPS1); DNA replication licensing factor MCM6; structural maintenance of chromosomes protein 1A (SMC1A); structural maintenance of chromosomes protein 3 (SMC3); and X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 6 (XRCC6).

Data analysis

In order to quantify peptide abundances in the PP2A dataset raw files were analyzed with MaxQuant version 1.5 (17) at 1% FDR. For the second dataset (16) MaxQuant tables were directly retrieved from their respective PRIDE repository locations (PXD002987).

In order to identify and quantify putative interactors of the bait proteins, raw peptide intensities obtained by MaxQuant were analyzed within the statistical environment R (18). Only unique peptides and proteins with a minimum of two identified peptides were considered for quantification. Median normalization between experiments was performed at the peptide level. Normalized peptide intensities were averaged within replicates in order to obtain protein abundances. Protein identifications were required to be present in at least two replicates of the respective bait. For the PP2A dataset, a plausible set of contaminants was downloaded from the CRAPome database version 1.1 (19), applying the following filters: cell/tissue type, HEK293; epitope tag, Strep-HA; subcellular fractionation, total cell lysate; affinity approach, streptactin; fractionation, 1D LC–MS; and instrument, LTQ-Orbitrap. Proteins observed in six or more CRAPome datasets were considered as contaminants. Protein identifications present in this list were filtered out as well as ribosomal proteins. Protein abundances across the same bait purifications were averaged and the significance of their fold-changes to the negative control was assessed by the Student's t-test. Protein identifications were regarded as interactors if their enrichment to the negative control was at least twofold and significant with a Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted P-value of 0.05. The abundance ratios to the respective bait were calculated and interactors with ratios <2% were not included. As a result we obtained a ‘Bait–Prey Interactions Table’ listing the putative bait–prey interactions with their respective abundance ratios.

The bait–prey interaction tables were used as input to infer prey–prey interactions. Pairwise cosine correlations were calculated using the prey-to-bait abundance ratios across different bait purifications. Hence, this mathematical term is referred to as abundance correlation. GO similarities were calculated using the getGeneSim function from the GOSim Bioconductor package (20) with the following parameters: similarity method, ‘dot’; normalization method, ‘sqrt’; and similarity term, ‘relevance’. UniProt accession numbers were mapped to Entrez IDs using the UniProt ‘Retrieve/ID mapping’ tool (21) and only ‘Biological Process’ and ‘Molecular Function’ categories were used. Their values were summarized by keeping the maximum of the two per protein–protein pair. Abundance correlations were combined with GO correlations by calculating the average of their values. Minimum thresholds of 0.8, 0.6 and 0.65 were allowed for abundance, GO and combined correlations, respectively. Proteins were clustered using the MCL algorithm (8) on either the abundance correlations, GO correlations or the combination of the two. Protein interactions were considered as true, if (i) any of the proteins was a bait and their correlation was above the respective threshold or (ii) both proteins were preys in the same MCL cluster with at least one showing a relative ratio to the bait >2%, and their correlation value above the respective threshold or (iii) at least one protein–protein contact was detected by XL–MS. The results are summarized in three different tables with interactions based on either abundance correlations, GO correlations or the combination of both correlations. These tables are annotated with the respective number of protein–protein contacts detected by XL–MS.

Result tables from the crosslink experiments were directly retrieved from the PRIDE database. Intra-protein crosslinks were filtered from the list whereas inter-protein crosslinks were summarized to number of crosslinks per protein–protein pair.

compleXView Analysis Module

compleXView offers two different modules, which operate independent of each other. One module is for the analysis of AP–MS data and performs part of the analysis workflow described in the previous section using protein abundances (Figure 1). Thus, the main input file for the ‘Analysis’ module is the ‘Purifications Table’ containing the protein abundances across all purifications. Its first column must be named ‘Prey’ and contains the protein IDs of the co-purified proteins. The second and all other columns must contain the abundances of the preys in each of the purification experiments. These columns have to be named according to the following format: BaitID__ReplicateNumber__Condition. The name in the ‘BaitID’ field must match the format of the entries in the ‘Prey’ column and the bait itself has to be detected in the respective purification. Negative controls must be named ‘NegCtr’ in this field. The ‘ReplicateNumber’ field contains any number or code for the identification of technical or biological replicates (e.g. R1, R2, R3). The ‘Condition’ field is optional and should be provided in cases where purifications of the same bait under different biological conditions are compared.

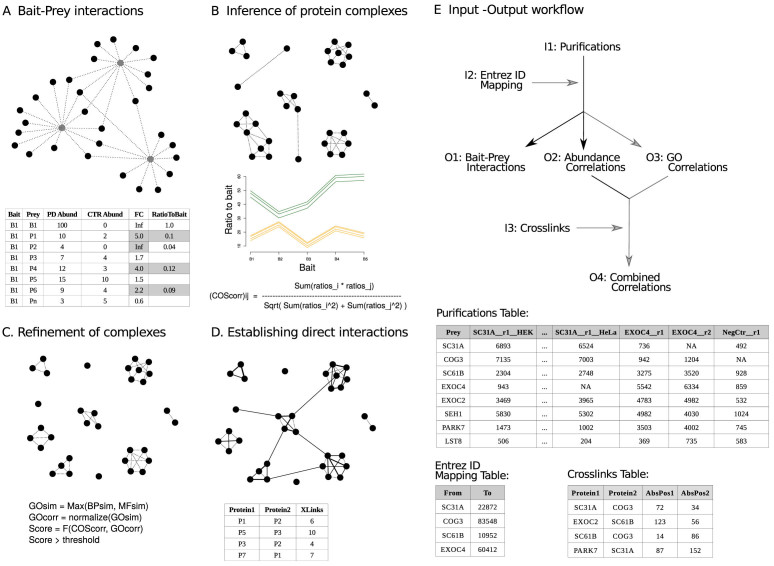

Figure 1.

Workflow of the compleXView ‘Analysis’ module. (A) bait–prey interactions are determined upon enrichment over the negative control and their relative abundance to the bait (PD, pull-down; CTR, control; FC, fold change). (B) Pairwise cosine correlations of prey abundance ratio profiles are used to infer interactions between preys. Subunits of a complex are expected to exhibit similar relative abundances to the bait across different bait purifications. Abundance correlations above a certain threshold value are selected for clustering the proteins into modules. (C) To eliminate spurious high correlations between two proteins, GO functional similarities between preys are used to refine the protein–protein interactions identified in the previous step. Highly correlated proteins with notably different molecular functions are scored lower. The combined score improves the resolution of the protein complexes in the network. (D) Protein interactions are inferred from quantitative AP–MS data. The final analysis step integrates direct protein interactions detected by XL–MS into the network and thereby, validates protein complexes and reveals inter-complex contacts. (E) Input (I1–I3) and output (O1–O4) tables required and generated by the compleXView ‘Analysis’ module (top panel) and example layouts of the input files. Grey arrows indicate optional files.

compleXView requires abundance values like iBAQ or other normalized intensities without log-transformation. Median or quantile normalization between conditions is optional. The basic output of the ‘Analysis’ module is the ‘Bait–Prey Interactions Table’ visualized as a spoke network. Abundance correlations will only be computed if the number of baits or conditions is >4. The output is a protein–protein interaction table that we call the ‘Abundance Correlations Table’.

In order to compute GO functional similarities between proteins an optional input table with two columns must be provided. The first column named ‘From’ contains the Protein IDs in the same format as in the ‘Prey’ column of the ‘Purifications Table’. The second column named ‘To’ contains the respective UniProt Entrez ID of the protein. The compleXView output is a protein–protein interaction table called ‘GO Correlations Table’, where each row contains a pair of preys and their corresponding GO similarity values.

For the implementation of inter-protein crosslinks an input table of at least four columns with the following headings is required: ‘Protein1’, ‘Protein2’, ‘AbsPos1’ and ‘AbsPos2’. The IDs in the first two columns should have the same format as the ‘Prey’ column in the ‘Purifications Table’. The numbers in the ‘AbsPos’ columns indicate the positions of the crosslinked amino acid residues.

The interactions in the output tables can be filtered according to different parameters like fold-change and p-value thresholds (see online Manual).

compleXView Visualization Module

The ‘Visualization’ module displays all bait–prey interaction tables and correlation-based tables generated by the ‘Analysis’ module (Figure 1E). Both modules operate independently which facilitates visualization of output tables generated by other programs, such as SAINT (3), MiST (4) or compPASS (5). The input table must contain two columns named ‘Bait’ and ‘Prey’ and optional columns to represent quantitative information.

The ‘Visualization’ module generates two types of representations the ‘Network’ and ‘Blot’ plots. The former represents proteins as circular nodes and linear edges indicate their interactions which are deduced from AP–MS abundances or indicated by XL–MS restraints. The ‘Blot’ plot is designed as western blot diagram displaying protein abundances across different bait purifications. ‘Blot’ plots are generated by selecting the respective nodes in the network and their quantitative interaction values determine the band intensities.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Workflow

compleXView comprises two independent modules: an ‘Analysis’ module and a ‘Visualization’ module. The workflow of the ‘Analysis’ module is schematically represented in Figure 1. compleXView exploits the quantitative information of multiple AP–MS experiments as well as GO functional annotations to infer protein complexes in protein interaction studies. Furthermore, compleXView implements XL–MS data to establish direct connectivity within or between the predicted complexes. The input data introduced as ‘Purifications Table’ is used by the ‘Analysis’ module to determine whether a detected protein is significantly enriched over the negative control and thus, considered as true interactor. Furthermore, only interactors whose relative abundances to the bait are greater than a specified threshold are considered (Figure 1A). The output is a table which serves as input file for the ‘Visualization’ module.

The ‘Bait–Prey Interactions Map’ derived from the quantitative AP–MS analysis of a limited number of baits do not provide enough protein connectivity to infer complexes in the network. compleXView overcomes this limitation by inferring the relation between preys based on calculating the correlation of their abundances profiles across different bait preparations. Accordingly, compleXView moves from a Spoke model of bait–prey interactions to a Matrix model of prey–prey interactions where correlations of abundances between all proteins are calculated. Abundance correlations are computed using the cosine similarity formula as schematically shown in Figure 1B. Although, abundance correlations may be capable of clustering the whole network into submodules and protein complexes, interactions between unrelated proteins may remain. To eliminate these incidents, compleXView retrieves GO functional terms and computes the similarity of the GO trees for every pair of proteins (Figure 1C). GO similarities are combined with the abundance correlations in order to obtain a network with higher resolution in terms of protein complex identification. Putative false interactions due to coincidentally occurring high correlations are resolved by accounting GO functional similarities. Low similarity values penalize correlations and only highly correlated or highly functionally similar protein–protein pairs remain.

The integration of direct protein connectivity information from XL–MS experiments with correlated protein abundances advances the approach, aids in inferring protein complex composition and provides additional topological information (Figure 1D). To integrate inter-protein crosslinks into correlation-based protein networks, the user has to provide a table listing the crosslinked amino acid positions between protein pairs. As demonstrated for the test datasets, XL–MS data confirms interactions within complexes and indicates contacts between them (Figures 1D and 4C).

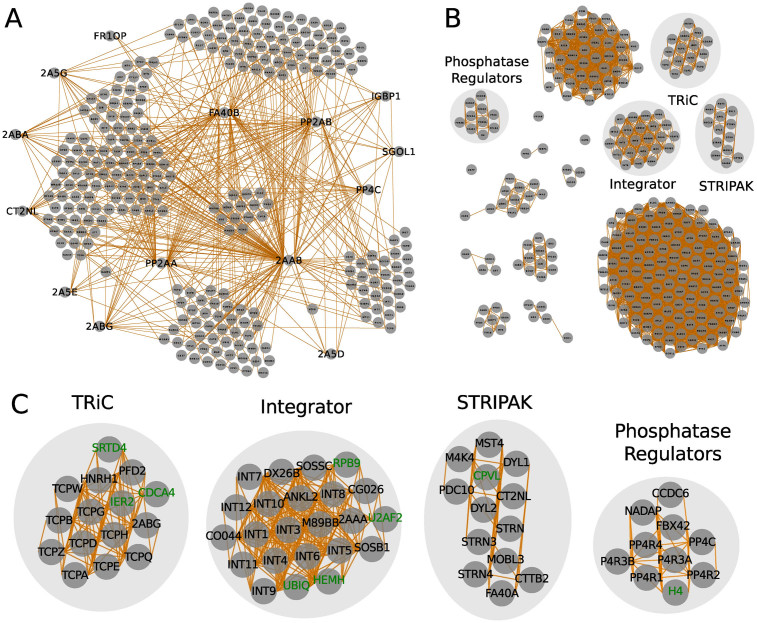

Figure 4.

compleXView analysis and visualization of the PP2A network based on crosslink-derived protein connectivity in combination with abundance and GO correlations. (A) Protein complexes in a PP2A network identified by inter-protein crosslinks. (B) Network of PP2A complexes based on the combination of abundance correlations, GO functional similarities and crosslinks. Crosslink-derived restraints validate interactions within predicted complexes, reveal inter-complex contacts and provide insights into the complex topology. Heat shock proteins and propionyl-CoA carboxylases detected in (A) did not pass the threshold values applied in (B). (C) Zoom-in on predicted clusters in (B). Interactions predicted by abundance correlations are indicated as dotted lines and interactions identified by crosslinks are depicted as solid lines.

Analysis of AP–MS / XL–MS Datasets

We tested compleXView on two different datasets which comprise AP–MS analyses and their respective XL–MS experiments (see Materials and Methods).

The first dataset of a PP2A network was obtained from purifications of PP2A core subunits, adapter and substrate proteins (Figure 2). The ‘Bait–Prey Interactions Map’ derived from data of the ‘Purifications Table’ depicts the co-purifying proteins of 14 different baits (Figure 2A). To reveal protein complexes in the network, computing abundance correlations between preys resulted in a network with a higher degree of connectivity. Clustering the proteins by a force-layout algorithm which applies the correlation values as measures of interaction strength is able to infer submodules and protein complexes in the network (Figure 2B). In particular, TRiC (TCP-1 ring complex), the Integrator and the STRIPAK complexes are discerned (Figure 2C) from co-purifying proteins. Remaining proteins are associated in large groups due to high random co-variation. Further clustering of proteins based on their GO functional similarities results in higher resolution of the indicated protein complexes in the network (Figure 3A) and reveals additional clusters and interactions (Figure 3B, C). Furthermore, compleXView facilitates the interactive manual inspection of putative interactions and protein clusters by providing links to the UniProt database.

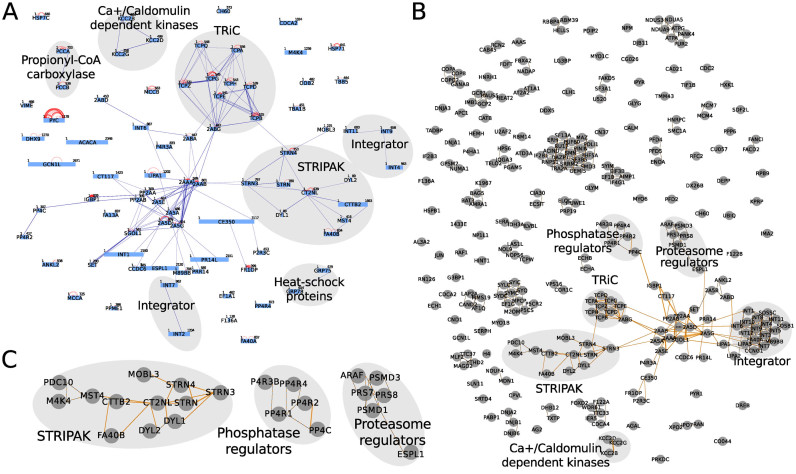

Figure 2.

PP2A complexes inferred from bait–prey interactions and abundance correlations. (A) bait–prey interactions of the PP2A network. Minimum relative abundance to the bait is 0.02 and the minimum enrichment over the negative control is 2.0. Proteins were grouped by a force-layout algorithm using relative abundances as measure for interaction strength and their inverse values as node-node initial distances. (B) PP2A complexes detected based on abundance correlations between preys. Correlation values >0.8 were considered as interactions. Proteins were clustered using the MCL algorithm, arranged by a force-layout algorithm using correlation values as interaction strength and the inverse values for node-node initial distances. (C) Zoom-in on complexes indicated in (B). Core subunits and interactors are depicted in black. Putative spurious interactions are shown in green.

Figure 3.

PP2A complexes predicted based on GO functional similarities alone and in combination with abundance correlations. (A) PP2A complexes inferred from GO similarities. Similarity values >0.6 were considered as interactions. Proteins were cluster using the MCL algorithm and arranged by a force-layout algorithm as described in (2A). (B) PP2A network analysis by applying abundance correlations combined with GO functional similarities between preys. Combined values >0.65 were considered as interactions. Proteins were clustered using the MCL algorithm and arranged by force-layout algorithm using combined values as interaction strength and the inverse values for node-node initial distances. (C) Zoom-in on complexes detected in (A) and (B).

The TRiC complex is revealed subsequent to clustering the proteins based on their abundance correlations (Figure 2C). Correlation values >0.9 are calculated between core components of the complex: TCPA, TCPB, TCPD, TCPE, TCPG, TCPH, TCPQ TCPW and TCPZ. In addition, known interactors of the TRiC core complex are identified: the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H (HNRH1), prefoldin subunit 2 (PFD2) and the PP2A regulatory subunit 2ABG. These interactions are annotated in the BioGRID and Intact databases. The associated proteins, SRTD4, IER2 and CDCA4, are putative interactors with high correlations to the TRiC complex. Clustering the network solely based on GO similarities only maintains the core subunits of the TRiC complex in the same group (Figure 3C). The functional similarities of HNRH1, PFD2 and 2ABG to TRiC subunits are low and their low correlation values are insufficient to keep them in the combined network.

Similarly, the Integrator complex is delimited upon clustering the proteins based on their abundance correlations. Integrator core subunits form a group with other known interactors, such as the ankyrin repeat and LEM domain-containing protein 2 (ANKL2), the PP2A regulatory subunit 2AAA, the integrator subunit 6-like (DX26B), the uncharacterized protein CG026, von Willebrand factor A domain-containing protein 9 (CO044), SOSS complex subunits C and B1 and the cell cycle regulator Mat89Bb homolog (Figure 2C). For the cluster members, RPB9, U2AF, UBIQ and HEMH, no previous evidence for their association with the Integrator complex has been reported. Interestingly, the Integrator complex was found to regulate RNA polymerase II activity (22) indicating that RPB9 may be directly associated with the Integrator complex and thus, these interactions have to be further evaluated. Clustering the network based on GO similarities maintains the Integrator core subunits in a group. However, many of the known Integrator interactors mentioned above are eliminated from the cluster. On the other hand, proteins, exclusively implicated by GO similarities in binding the Integrator complex, are possibly false interactors as their high GO similarity scores result from very general ‘Molecular Process’ terms (Figure 3C). Moreover, they lack previous evidence of interaction with the Integrator in the BioGRID and Intact databases and are removed from the cluster upon combining abundance correlations with GO similarities. The presence of LIPA1 and 2 in the cluster is due to its high correlation with LIPA3 which is based on a general Molecular Function similarity to Integrator subunits (Figure 3C).

Clustering based on abundance correlations also distinguishes the STRIPAK complex comprising kinases and kinase-associated proteins such as MAP4K4, MST4 and PDCD10 and proteins which interact with striatin like dynein light chains (DYL1 and 2), the Mps one binder-like protein (MOBL3) and the Cortactin-binding protein 2 (CTTB2) (Figure 2C). However, applying GO similarities alone or in combination with abundance correlations results in loss of STRIPAK interacting proteins (Figure 3C) Thus, correct clustering based on weaker abundance correlations may be abrogated once combined with GO functional similarities.

Regulatory subunits of protein phosphatase 4 (PP4) are clustered by applying abundance correlations. However, regulatory subunits of PP2A are dispersed in different groups in the network (Figure 2C). Clustering solely based on GO similarities groups all PP2A regulatory subunits into a cluster and leaves some PP4 regulators outside (Figure 3C). In this case, the clustering with abundance correlations and functional similarities splits the PP2A regulators into subgroups and unifies PP4 regulators with its original cluster.

Bait–prey and prey–prey interactions which are abundant in the affinity-purifications are usually sufficiently covered by the XL–MS analysis detecting at least one crosslink per interaction. Hence, the composition and topology of the PP2A core complexes, TRiC and the STRIPAK complex were revealed solely based on inter-protein crosslinks (Figure 4A). Protein interactions below the detection limit of XL–MS were inferred from AP–MS data revealing clusters of phosphatase and proteasome regulators and interactions of MAP4K4 and PDC10 with the STRIPAK complex (Figure 4B). Thus, the integration and visualization of AP–MS and XL–MS data through compleXView analysis complements the protein interactions of complexes indicated by crosslink-derived restraints and validates interactions inferred from abundance correlations (Figure 4C).

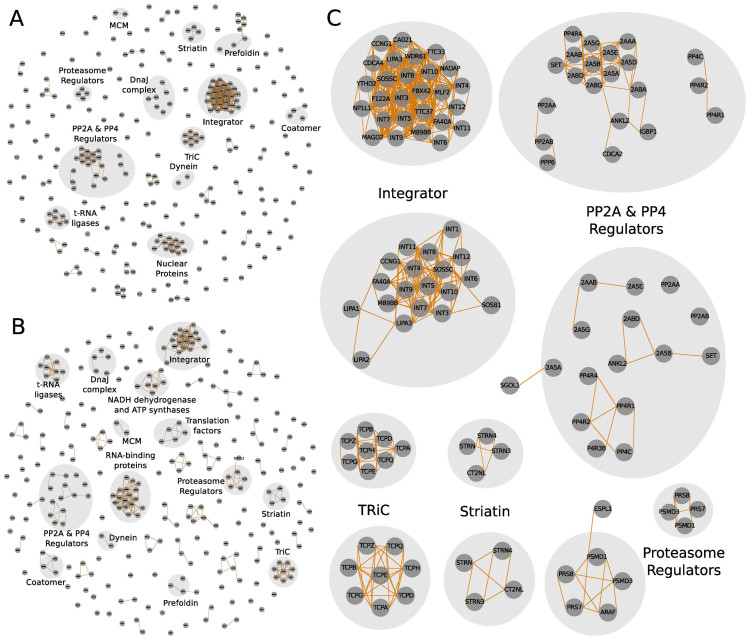

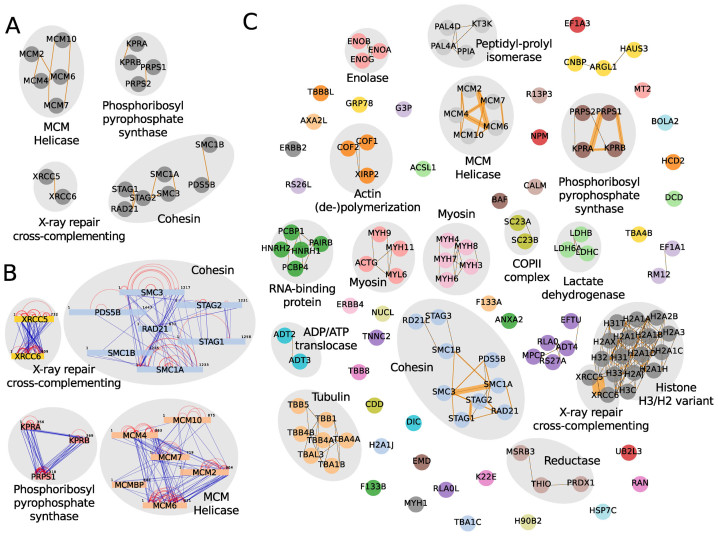

The second dataset analyzed by compleXView is comprised of five bait proteins with four of them assembled in chromatin-associated complexes and one enzyme involved in the nucleotide metabolic pathway (16). Clustering solely based on abundance correlations did not resolve these protein complexes (data not shown). Indeed, clustering by GO similarities alone was sufficient to group many subunits into the respective complexes (Figure 5A). Importantly, only the combination of both, abundance correlations and GO functionalities, associated STAG3 and RD21L to the cohesin complex and PRPS2 to the phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthase complex (Figure 5C). Several other complexes with relative abundances <10% of the bait, which were not detected by XL–MS, were distinguished (Figure 5B and C).

Figure 5.

compleXView analysis and visualization of chromatin-associated complexes (16) applying abundance correlations combined with GO functional similarities and inter-protein crosslinks. (A) Zoom-in on the network solely based on GO similarities depicting only bait complexes. Co-purifying complexes are shown in (C). (B) Inter-protein crosslink network. (C) Network of protein complexes detected by the combination of abundance correlations, GO functional similarities and inter-protein crosslinks.

compleXView offers interactive graphical features for the manipulation and interpretation of the interaction maps. In single-bait experiments users can color preys based on their relative abundances and multiple purifications can be directly compared in a ‘Blot’ plot representation (see online Manual for detailed description).

compleXView aims to provide an analysis tool for biologists to identify and interpret protein complexes in their pull-down studies. In particular, the combination and visualization of quantitative and connectivity data obtained by mass spectrometry complements the standard maps of co-purifying proteins with structural restraints between subunits and modules in the network.

FUNDING

LMUexcellent Initiative, the Bavarian Research Center of Molecular Biosystems (to F.H.); German Excellence Initiative (Graduate School QBM); German Research Foundation [GRK1721], the European Research Council [MolStruKT StG no. 638218]; Human Frontier Science Program Research Grant [RGP0008/2015]. Funding for open access charge: Bavarian Research Center of Molecular Biosystems.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Leitner A., Walzthoeni T., Kahraman A., Herzog F., Rinner O., Beck M., Aebersold R.. Probing native protein structures by chemical cross-linking, mass spectrometry and bioinformatics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2010; 9:1634–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu F., Heck A.J.. Interrogating the architecture of protein assemblies and protein interaction networks by cross-linking mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2015; 35:100–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Choi H., Larsen B., Lin Z.-Y., Breitkreutz A., Mellacheruvu D., Fermin D., Qin Z.S., Tyers M., Gingras A.-C., Nesvizhskii A.I.. SAINT: probabilistic scoring of affinity purification-mass spectrometry data. Nat. Methods. 2011; 8:70–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jäger S., Cimermancic P., Gulbahce N., Johnson J.R., McGovern K.E., Clarke S.C., Shales M., Mercenne G., Pache L., Li K. et al. . Global landscape of HIV-human protein complexes. Nature. 2012; 481:365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sowa M.E., Bennett E.J., Gygi S.P., Harper J.W.. Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell. 2009; 138:389–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bader G.D., Hogue C.W. V. Analyzing yeast protein–protein interaction data obtained from different sources. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002; 20:991–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gavin A.-C., Aloy P., Grandi P., Krause R., Boesche M., Marzioch M., Rau C., Jensen L.J., Bastuck S., Dümpelfeld B. et al. . Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature. 2006; 440:631–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hart G.T., Lee I., Marcotte E.R.. A high-accuracy consensus map of yeast protein complexes reveals modular nature of gene essentiality. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007; 8:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krogan N.J., Cagney G., Yu H., Zhong G., Guo X., Ignatchenko A., Li J., Pu S., Datta N., Tikuisis A.P. et al. . Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2006; 440:637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Enright A.J., Van Dongen S., Ouzounis C.A.. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30:1575–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bader G.D., Hogue C.W. V. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003; 4:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leung H.C.M., Xiang Q., Yiu S.M., Chin F.Y.L.. Predicting protein complexes from PPI data: a core-attachment approach. J. Comput. Biol. 2009; 16:133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kouhsar M., Zare-mirakabad F., Jamali Y.. WCOACH: protein complex prediction in weighted PPI networks. Genes Genet. Syst. 2015; 90:317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grimm M., Zimniak T., Kahraman A., Herzog F.. XVis: a web server for the schematic visualization and interpretation of crosslink-derived spatial restraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:W362–W369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herzog F., Kahraman A., Boehringer D., Mak R., Bracher A., Walzthoeni T., Leitner A., Beck M., Hartl F.-U., Ban N. et al. . Structural probing of a protein phosphatase 2A network by chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Science. 2012; 337:1348–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Makowski M.M., Willems E., Jansen P.W.T.C., Vermeulen M.. Cross-linking immunoprecipitation-MS (xIP-MS): Topological analysis of chromatin-associated protein complexes using single affinity purification. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2016; 15:854–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cox J., Mann M.. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008; 26:1367–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 20016; Vienna. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mellacheruvu D., Wright Z., Couzens A.L., Lambert J.-P., St-Denis N.A., Li T., Miteva Y. V, Hauri S., Sardiu M.E., Low T.Y. et al. . The CRAPome: a contaminant repository for affinity purification-mass spectrometry data. Nat. Methods. 2013; 10:730–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fröhlich H., Speer N., Poustka A., Beissbarth T.. GOSim–an R-package for computation of information theoretic GO similarities between terms and gene products. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007; 8:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. The UniProt Consortium UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 43:D204–D212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stadelmayer B., Micas G., Gamot A., Martin P., Malirat N., Koval S., Raffel R., Sobhian B., Severac D., Rialle S. et al. . Integrator complex regulates NELF-mediated RNA polymerase II pause/release and processivity at coding genes. Nat. Commun. 2014; 5:5531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]