Abstract

Background.

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) is one of the most common malignant brain tumors in infants. Although cancer stem cells of AT/RT express aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), effective chemotherapies against AT/RT have not been established. Here, we examined radiosensitizing effects of disulfiram (DSF), an irreversible inhibitor of ALDH against AT/RT for a novel therapeutic method.

Methods.

Patient-derived primary cultured AT/RT cells (SNU.AT/RT-5 and SNU.AT/RT-6) and established AT/RT cell lines (BT-12 and BT-16) were used to assess therapeutic effects of combining DSF with radiation treatment (RT). Survival fraction by clonogenic assay, protein expression, immunofluorescence, and autophagy analysis were evaluated in vitro. Antitumor effects of combining DSF with RT were verified by bioluminescence imaging, tumor volume, and survival analysis in vivo.

Results.

The results demonstrated that DSF at low concentration enhanced the radiosensitivity of AT/RT cells with reduction of survival fraction to 1.21‒1.58. DSF increased DNA double-strand break (γ-H2AX, p-DNA-PKcs, and p-ATM), apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3), autophagy (LC3B), and cell cycle arrest (p21) in irradiated AT/RT cells, while it decreased anti-apoptosis (nuclear factor-kappaB, Survivin, and B-cell lymphoma 2 [Bcl2]). In vivo, DSF and RT combined treatment significantly reduced tumor volumes and prolonged the survival of AT/RT mouse models compared with single treatments. The combined treatment also increased γ-H2AX, cleaved caspase-3, and LC3B expression and decreased ALDH1, Survivin, and Bcl2 expression in vivo.

Conclusions.

DSF and RT combination therapy has additive therapeutic effects on AT/RT by potentiating programmed cell death, including apoptosis and autophagy of AT/RT cells. We suggest that DSF can be applied as a radiosensitizer in AT/RT treatment.

Keywords: AT/RT, DNA damage, DSF, radiation therapy, radiosensitizer

Importance of the study

AT/RT contains distinct subpopulations of cells that have high expression levels of ALDH and cancer stem cell (CSC) characteristics. Here, we showed significant therapeutic effects of an ALDH inhibitor, DSF, against AT/RT using patient-derived primary cells and orthotopic animal models to translate experimental DSF treatment into clinical trials. The DSF dramatically potentiated the anticancer effect of RT on AT/RT in vitro and in vivo. As DSF is a clinically applicable drug that is currently used for alcoholism in clinic and RT is currently used as one of the standard treatments for AT/RT, the additive effects of DSF + RT combination therapy would increase the clinical relevance of the CSC targeting treatment. Radiosensitizing effects of DSF would also broaden the applicability of RT to young AT/RT patients via reducing radiation dose.

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) is a highly malignant CNS tumor that predominantly arises in children less than 3 years of age.1 Although mutations and functional loss of the SMARCB1 gene is almost pathognomonic for AT/RT,2,3 recent genomic research has revealed that AT/RT is a heterogeneous group of tumors. Torchia et al4 reported that expression of achaete-scute homolog 1, a regulator of Notch signaling, correlates with supratentorial location and superior 5-year overall survival. Moreover, Johann et al suggested 3 molecular subgroups of AT/RT, termed AT/RT-TYR, AT/RT-SHH, and AT/RT-MYC. These groups are genetically similar but differ in SMARCB1 mutation pattern, epigenetic and gene expression signature, and patients’ survival.4,5 Despite these advances in research, numerous clinical attempts for AT/RT treatment, including surgical resection, high-dose chemotherapy, radiation therapy (RT), and/or proton therapy, have resulted in only limited responses with poor prognosis.6–11 Therefore, novel therapeutic modalities with different treatment mechanisms are required for young patients with this dismal disease.

Targeting cancer stem cells (CSCs), a rare cancer cell population in AT/RT, could be a solution to reverse the poor response of AT/RT to conventional anticancer treatments because CSCs preferentially survive the therapies that are currently being used.12 CSCs utilize different metabolic pathways to show their characteristics. In CNS malignancies, CSCs have been reported to express aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), a polymorphic enzyme responsible for the oxidation of aldehydes to carboxylic acids. Although the functional mechanisms of ALDH in the CSCs of CNS malignancies have not been fully elucidated, the targeted knockdown of ALDH in CSCs potently disrupted their self-renewing ability. Notably, an ALDH inhibitor, disulfiram (DSF), decreased the stemness and proliferation of ALDH-expressing AT/RT cells as well as increased apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.12

In our previous study, we observed that DSF significantly sensitizes AT/RT cells to irradiation in vitro.12 This indicated that DSF, an alcoholism treatment drug that inhibits the conversion of acetaldehyde to acetic acid,13,14 could be repositioned as a radiosensitizer for AT/RT because RT is commonly used to treat AT/RT patients in the clinic. However, the radiosensitizing activity of DSF in AT/RT cells needs to be reproduced in vivo, and its treatment mechanisms should be elucidated before being translated to patient treatment. Accordingly, the goal of this study was to evaluate the anticancer additive effect of the DSF and RT combination against AT/RT in vivo and to confirm the potent radiosensitizing activity of DSF on AT/RT cells. In addition, we proposed the possible treatment mechanisms of DSF and RT combination therapy. For the first time, this study demonstrated the in vivo additive effects of DSF and RT combination therapy against AT/RT, which is mediated by programmed cell death including apoptosis and autophagy.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

AT/RT surgical samples were derived from 2 patients who had surgical treatment at the Seoul National University Children’s Hospital (a 9-month-old boy [SNU.AT/RT-5] and a 13-month-old boy [SNU.AT/RT-6]) upon receipt of the appropriate written consent approved by the institutional review board of the Seoul National University Hospital (#1501-139-639). The pathologic diagnosis of AT/RT was made histologically and was confirmed by the loss of expression of Integrase interactor 1/Switch sucrose nonfermentable related, matrix associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily B (INI-1/SMARCB1).15 AT/RT cells were primarily cultured from the surgical samples as described previously.16 The established AT/RT cell lines BT-12 and BT-16 were provided by Dr Peter Houghton (Nationwide Children’s Hospital). All AT/RT cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Welgene) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies) and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in an incubator in 5% CO2 atmosphere. AT/RT primary cells under in vitro passage 5 were used in all experiments in this study. All AT/RT cells were checked to be free of mycoplasma contamination, and cell line authentification by DNA fingerprinting was executed.

DSF and/or Radiation Treatment

To define the appropriate doses of DSF and RT for each cell line, we first examined 72-hour short-term cell viability escalating single doses of DSF (0 to 10000 nM) or radiation (0 to 6 Gy). DSF (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich). The AT/RT cells (2 × 103/well) were cultured on 96-well plates for 24 h. Complete medium containing dimethyl sulfoxide was used as the negative control. The cells were treated with DSF or irradiated using a Varian Clinac 6EX (Varian Medical Systems). After 72 h of incubation, the cell viability was measured using an EZ-cytox kit (Daeil Lab Service). The inhibitory concentration of 10% (IC10) of DSF on AT/RT cells was determined and utilized in the following experiments.

Clonogenic Assay and Sensitizer Enhancement Ratio Analysis

AT/RT cells (1 × 103) were cultured in 6-well plates for 24 h. The cells were treated with IC10 DSF, irradiated (0, 2, 4, or 6 Gy), and then maintained for 7–14 days to form colonies. The colonies were stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution. Colonies with over 50 cells were counted. The cell survival curves were obtained by fitting 3 surviving fractions into the linear-quadratic model17 using CS-Cal clonogenic survival calculation software (http://angiogenesis.dkfz.de/oncoexpress/software/cs-cal/index.htm). The sensitizer enhancement ratio (SER) was calculated as the ratio of the radiation dose required to achieve surviving fraction (SF) values of 0.5 in the absence of DSF to that in the presence of DSF.18

Western Blot Analysis

Total proteins were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, and 50 µg of proteins were used for western blot analysis. Primary antibodies were used against ALDH1 (1:500, Abcam), nuclear factor-kappaB (NFκB) (1:2000, Abcam), γ-H2AX (1:500, Abcam), DNA-PKcs (1:500, Abcam), p-ATM (1:500, Abcam), cleaved caspase-3 (1:200, Millipore), Survivin (1:2000, Abcam), B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl2) (1:500, Abcam), LC3B (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology), p21 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich). The blots were performed as previously reported.19

Immunofluorescence of γ-H2AX and Cleaved Caspase-3

The AT/RT cells (1 × 103/well for γ-H2AX or 5 × 103/well for cleaved caspase-3) were seeded in 8-well chamber slides (Lab-Tek) and treated with DSF and/or radiation. Immunofluorescence staining was performed with anti–γ-H2AX (1:500, Abcam) or anti–cleaved caspase-3 antibody (1:50, Millipore) as described previously.20 The stained cells were observed in 3 random fields using a fluorescence microscope.

Autophagy Assay

The AT/RT cells (1 × 103/well) were seeded in 8-well chamber slides (Lab-Tek), then incubated for 24 h. Seven days after DSF and/or RT, specifically labeled autophagic compartments were observed using fluorescence microscopy according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Enzo Life Sciences). Briefly, AT/RT cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 5% FBS, stained with Microscopy Dual Detection Reagent (Cyto-ID and Hoechst) for 30 min at 37 °C, and then washed twice with Assay Buffer. Cyto-ID–stained cells were visualized by fluorescein isothiocyanate filter set fluorescence microscopy.

Intracranial Orthotopic AT/RT Mouse Model

All of the animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC number: 14-0204-C1A0(1)) at the Seoul National University and were conducted in accordance with the “National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH publication no. 80-23, revised in 1996). Eight-week-old female BALB/c nude mice (JungAng Lab Animal) were anesthetized by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 30 mg/kg Zoletil (Virbac) and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Bayer). BT-16 expressing luciferase (BT-16-effLuc) cells were used for bioluminescence imaging as described previously.21 BT-16-effLuc cells (1.2 × 105 in 3 µL of phosphate-buffered saline) were injected stereotactically into the brains using a 26-gauge Hamilton syringe at an injection rate of 1 µL/min. Stereotactic coordinates were 1 mm anterior and 2 mm lateral to the bregma and 3 mm depth from the dura.12

Tumor Volume and Immunofluorescence Analysis

Six days after injection of BT-16-effLuc cells, the mice were randomized into 4 groups (n = 5 for each group): saline (control), DSF-treated group (DSF), radiation-treated group (RT), and combined DSF- and RT-treated group (DSF + RT). The mice were i.p. injected with saline or 25 mg/kg DSF for 5 consecutive days. The dose of DSF was determined as one quarter of the effective dose (100 mg/kg) based on our previous study.12 One day after the DSF treatment, the RT and DSF + RT group of mice had 5 Gy of irradiation using a Varian Clinac 6EX.22–24 We used 5 Gy for the in vivo tumor model to overcome differences with the in vitro condition. Followed by a 3-day resting period, the DSF + RT treatment cycle was repeated. The mice were sacrificed for histological analysis 56 days after tumor cell injection. After perfusion, frozen tissue sectioning was performed as previously reported.19 The tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to access the tumor volume. Immunofluorescence was performed using the following primary antibodies: ALDH1 (1:100, Abcam), Ki-67 (1:150, Abcam), γ-H2AX (1:500, Abcam), cleaved caspase-3 (1:100, Millipore), Survivin (1:200, Abcam), Bcl2 (1:200, Abcam), and LC3B (1:400, Cell Signaling Technology). Quantification of positively stained cells was performed from at least 3 randomly stained regions using a fluorescence microscope.

In vivo Live Imaging and Survival Analysis

Non-invasive in vivo monitoring of brain tumor growth via bioluminescence images was performed (n = 8 for each group). The treatment schedule for the evaluation of survival was the same as the scheme for tumor volume analysis. The mice brains were imaged using an IVIS-100 system (Xenogen) equipped with a charge-coupled device camera (Caliper Life Sciences) every 7 days. The mice received an i.p. administration of 150 mg/kg D-Luciferin (Caliper Life Sciences) and then were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Piramal Healthcare) in 100% O2. Images were acquired by recording the bioluminescent signal for 3–5 min and were analyzed with Living Image software (Xenogen). Bioluminescence was quantified by calculating the luminescence intensity in regions of interest. All of the animals were followed until euthanasia or the survival endpoint of 150 days.

Statistical Analysis

All of the results were calculated as means±SD or were expressed as percentages of controls ± SD from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using 2-tailed Student’s t-test. The survival data were presented by Kaplan–Meier survival graphs using GraphPad Prism 5 software and were analyzed by the log-rank test. A P-value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Significant Radiosensitizing Effects of DSF on AT/RT Cells

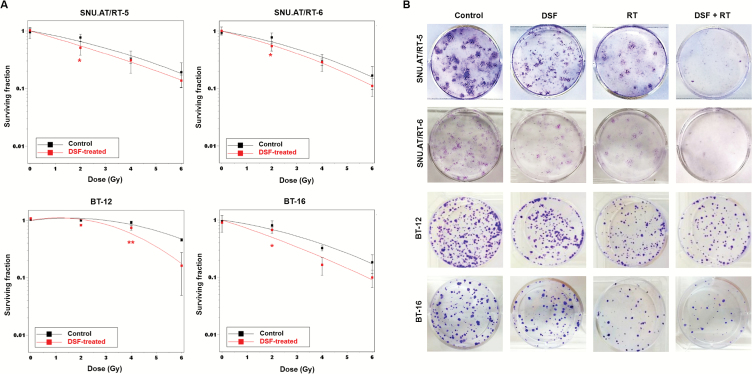

We estimated IC10 of DSF against each AT/RT cell line by short-term cell viability analysis: 50 nM in SNU.AT/RT-5; 50 nM in SNU.AT/RT-6; 24 nM in BT-12; and 2 nM in BT-16 (Supplementary Fig. S1). To determine whether IC10 of DSF enhances the sensitivity of the cells to RT, clonogenic assay was performed. The SER at SF of 0.5 (SER0.5) was 1.30 in SNU.AT/RT-5; 1.21 in SNU.AT/RT-6; 1.35 in BT-12; and 1.58 in BT-16 (Fig. 1A, Table 1). The clonogenic assay showed that the DSF + RT combination treatment significantly reduced colonies compared with single-treated groups (Fig 1B). These results indicate that DSF acts as a radiosensitizer against AT/RT cells.

Fig. 1.

In vitro radiosensitizing effects of DSF on AT/RT cells. (A) The surviving fractions of AT/RT cells at various doses of irradiation ± IC10 DSF were compared. (B) The clonogenic assay was performed to determine the treatment effects of IC10 of DSF and/or irradiation (50 nM + 2 Gy for SNU.AT/RT-5 and SNU.AT/RT-6; 24 nM + 4 Gy for BT-12; 2 nM + 2 Gy for BT-16). Surviving colonies after treatment were stained and illustrated. *P < .05, **P < .01.

Table 1.

Sensitizer enhancement ratio (SER) in AT/RT cells

| Cells | Radiation dose of SF of 0.5 | SER0.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | DSF | ||

| SNU.AT/RT-5 | 3.01 | 2.31 | 1.30 |

| SNU.AT/RT-6 | 2.92 | 2.41 | 1.21 |

| BT-12 | 5.85 | 4.34 | 1.35 |

| BT-16 | 3.15 | 1.99 | 1.58 |

SER was calculated as the radiation dose needed for radiation only divided by the dose needed for IC10 of DSF with radiation at surviving fraction (SF) of 0.5.

Radiosensitizing Mechanisms of DSF

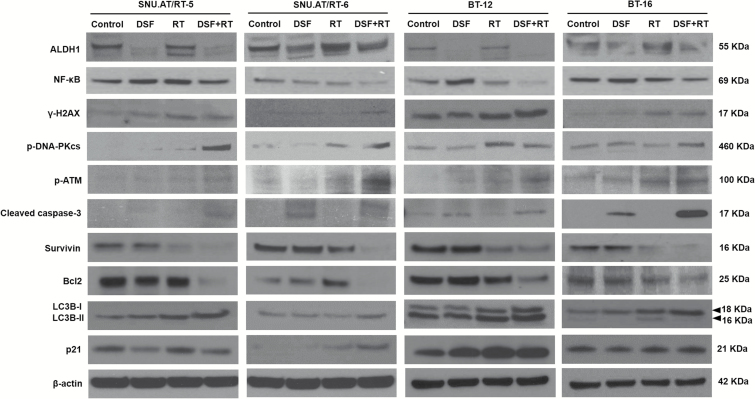

We examined the protein expression related to the DNA damage response, apoptosis, autophagy, and cell cycle arrest in SNU.AT/RT-5, SNU.AT/RT-6, BT-12, and BT-16 cells (Fig. 2). DNA double-strand break markers (γ-H2AX, p-DNA-PKcs, and p-ATM), an apoptotic marker (cleaved caspase-3), an autophagy marker (LC3B-II), and a cell cycle arrest protein (p21) were increased in the DSF + RT group compared with the single-treatment groups. By contrast, the combination group showed a decrease in the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as NF-κB, Survivin, and Bcl2. These data indicate that DSF enhances DNA damage by irradiation, which would potentiate apoptosis, autophagy, and cell cycle arrest. Interestingly, ALDH1 expression was reduced by DSF, an ALDH inhibitor.

Fig. 2.

Radiosensitizing mechanisms of DSF. The expression of ALDH1, NF-κB, γ-H2AX, p-DNA-PKcs, p-ATM, cleaved caspase-3, Survivin, Bcl2, LC3B-I and -II, and p21 was analyzed in SNU.AT/RT-5, SNU.AT/RT-6, BT-12, and BT-16 cells by western blotting.

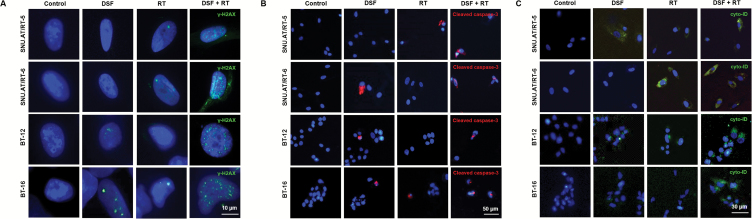

DNA Damage, Apoptosis, and Autophagy Are Enhanced by DSF in Irradiated AT/RT Cells

We carried out γ-H2AX immunofluorescence to confirm the effect of DSF on DNA damage. γ-H2AX foci were minimally observed in the control, DSF, and RT alone groups. By contrast, the numbers of γ-H2AX foci dramatically increased in the DSF + RT combination group of all 4 AT/RT cells (Fig. 3A). Apoptotic cells stained with cleaved caspase-3 were significantly increased in the DSF + RT group compared with the single-treatment group (Fig. 3B). Enhanced autophagy by DSF in irradiated AT/RT cells was confirmed by autophagy-visualization with Cyto-ID. In the DSF + RT groups of all 4 AT/RT cells, the accumulation of autophagy was increased significantly compared with the other groups (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these data confirmed that DSF enhances DNA damage via apoptosis and autophagy in irradiated AT/RT cells.

Fig. 3.

Effects of DSF on the DNA damage and autophagy of irradiated AT/RT cells. (A) γ-H2AX foci-positive cells (green) in each group were compared by immunofluorescence (n = 3 for each group). Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Apoptosis was confirmed by cleaved caspase-3-stained cells (red) by immunofluorescence (n = 3 for each group). Scale bar, 50 μm. (C) The autophagy-induced cells were observed by Cyto-ID uptake (green). Scale bar, 30 μm. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). All of the experiments were performed in SNU.AT/RT-5, SNU.AT/RT-6, BT-12, and BT-16 cells.

In vivo Short-term Therapeutic Efficacy

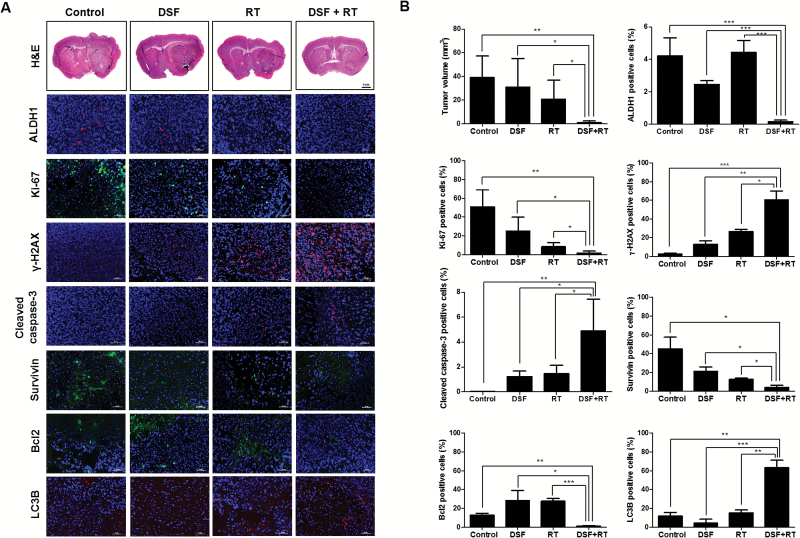

To confirm the radiosensitizing effect of DSF in vivo, an AT/RT intracranial orthotopic mouse model was established using BT-16-effLuc cells as described previously.12 The treatment schedule is indicated in Fig. 4A. Changes in the tumor volume by treatments were pathologically examined at 56 days. The tumor volume of the DSF + RT group (1.02 ± 1.38 mm3) was significantly smaller than that of the control (39.12 ± 18.17 mm3, P < .01), DSF (31.23 ± 23.91 mm3, P < .05), and RT groups (20.80 ± 16.25 mm3, P < .05, Fig. 4B). Together, these results indicate that the DSF + RT combination treatment is dramatically more effective than the single treatments in reducing the tumor volume.

Fig. 4.

In vivo radiosensitizing effects of DSF. Mice transplanted with AT/RT cells were randomly grouped into the control, DSF, RT, or DSF + RT group. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunofluorescence against ALDH1, Ki-67, γ-H2AX, cleaved caspase-3, Survivin, Bcl2, and LC3B were performed at day 56. Magnification for H&E, ×1.25. The outlines indicate tumor margins. Scale bar for immunofluorescence, 50 µm. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). (B) The tumor volume and positive cell number for ALDH1, Ki-67, γ-H2AX, cleaved caspase-3, Survivin, Bcl2, and LC3B were quantified and compared (n = 3 for each group). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

In addition, the in vivo effects of DSF on irradiated AT/RT cells were examined by immunofluorescence of the AT/RT tumor tissues. ALDH1, Ki-67, Survivin, and Bcl2 expression decreased significantly, whereas the expression of γ-H2AX, cleaved caspase-3, and LC3B increased significantly in the DSF + RT group compared with the other groups (Fig. 4B). These results were consistent with previous in vitro data.

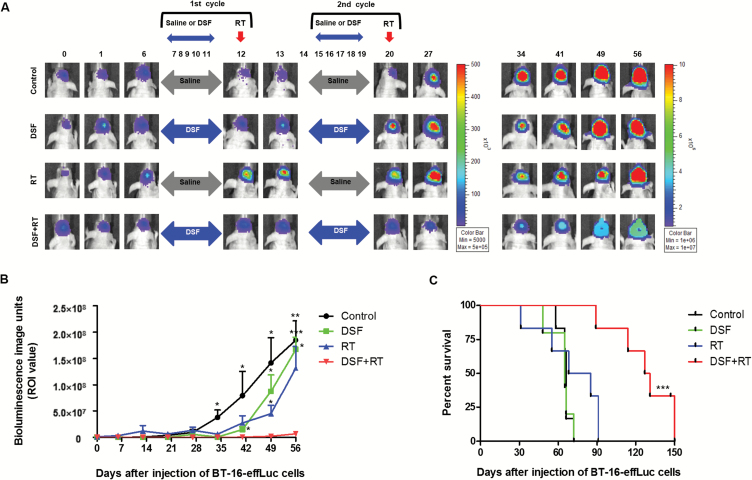

In vivo Long-term Therapeutic Efficacy

The noticeable in vivo therapeutic effects of the DSF and RT combination treatment were visualized and further evaluated by survival analysis. The AT/RT animal models and treatment schedules were identical to those in previous experiments. The treatment dosage was also the same as 25 mg/kg DSF and 5 Gy RT. The effect of DSF and RT was analyzed by bioluminescence intensity at a median region of interest (Fig. 5A and B). Although the DSF or RT single treatment reduced the tumor volumes at the initial stage of treatment (day 35), the effects did not last one month after the treatment (days 49 and 56). By contrast, the bioluminescence of the DSF + RT group did not increase significantly until day 56, when the mice in the other groups were euthanized due to the huge tumor volume.

Fig. 5.

Long-term treatment effects of the DSF and RT combination therapy. (A) Bioluminescence images (BLI) were obtained at various time-points using an IVIS-100 imaging machine. (B) Tumor growth was quantified by BLI and compared. (C) The median survival time of the groups (days) was illustrated by Kaplan–Meier survival curves and compared using the log-rank test. DSF + RT combination therapy showed survival benefit compared with other groups. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Long-term median survival results showed that the DSF + RT group (129 days) lived significantly longer than the control (66 days), DSF (65 days), and RT (76.5 days) groups (P < .001, Fig. 5C). There were no differences in the survival length between the control and single-treatment groups.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the DSF and RT combination treatment significantly reduced tumor volumes and dramatically prolonged the survival length of mice with AT/RT. In the clinical setting, RT is usually reserved for brain tumor patients older than 3 years. Unfortunately, AT/RT is prevalent in children younger than 3 years.10 Therefore, limited application of RT is a significant hurdle in the treatment of AT/RT. Recently, clinical trials applied RT to patients older than 1.5 years.25 However, many centers hesitate to apply this protocol because of delayed RT sequels in the young children. Herein, we suggest DSF as a radiosensitizer that enhances the therapeutic effect of radiation. The introduction of radiosensitizer might broaden the applicability of RT to AT/RT patients younger than 3 years by adjusting the radiation dose.

DSF has been used for over 60 years as an off-patent drug for ethanol abuse. The absorption of DSF occurs in the gastrointestinal tract and it is sequentially converted to its active metabolites: diethyldithiocarbamate (DDC), diethyldithiomethylcarbamate (Me-DDC), and diethylthiomethylcarbamate (Me-DTC).26,27 The metabolic molecules can also penetrate the blood‒brain barrier.28,29 In the present study, we confirmed that DSF inhibited ALDH enzyme activity and regulated expression of NF-κB in AT/RT cells. In addition, DSF significantly increased the expression of DNA double-strand break markers (γ-H2AX, p-DNA-PKcs, and p-ATM), an apoptotic marker (cleaved caspase-3), an autophagy marker (LC3B), and a cell cycle arrest protein (p21), and decreased the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins (NF-κB, Survivin, and Bcl2) in irradiated AT/RT cells or orthotopic tumors. These data indicate that induced DNA damage, apoptosis, autophagy, and cell cycle arrest might be involved in the radiosensitization of DSF in AT/RT. Although the essential mediator of diverse phenotypes provoked by DSF needs to be elucidated further, NF-κB could be a candidate, since it is a key player which connects DNA damage and programmed cell death.30,31

As CSCs are more resistant to radiation therapy than non-CSCs,32 their characteristics can provide clues to make novel treatment modalities reverse the radiation resistance of brain tumors. The CSCs of brain tumors express specific surface proteins such as CD13333 and CD15,34 but their functional implications in CSCs are unclear. Moreover, specific inhibitors for the surface antigens are hard to make because they do not have enzymatic activities. However, ALDH is an attractive candidate for targeting CSCs especially in AT/RT for 2 reasons. First, ALDH is universally expressed in CSCs in various primary brain tumors, including AT/RT. Notably AT/RT has a very high ALDH+ fraction of more than 20% of cells.20 Second, the therapeutic effects of RT are profoundly affected by the metabolic status of cancer cells, especially the oxidative status.35 Although CSCs are usually cultured in serum-free conditions, in this study the AT/RT cells were cultured in monolayer conditions with FBS. We compared the ALDH+ cell ratio between serum-free and FBS-containing media and found that early passage tumor cells in the FBS condition still have comparable tumor cells with ALDH enzyme activity. The differential expression of metabolic enzymes such as ALDH could be used to target CSCs combined with RT.

To overcome the radioresistance, various types of chemicals have been developed and tested.36 Most importantly, many agents have focused on re-oxygenating hypoxic tumor tissues using several action mechanisms such as hypoxic cytotoxicity and the enhancement of oxygen diffusion.37,38 Others inhibit key enzymes of DNA damage repair signaling (ie, ATM, ATR, CHK1, CHK2, and PARP) or cell survival signaling (ie, epidermal growth factor receptor, [11C]methyl-L-methionine, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt, and mammalian target of rapamycin).39–41 Along with those targeted agents, nonspecific cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents, including temozolomide, have been tested.42,43 It has also been suggested that DSF supplemented with copper is a promising therapeutic agent.29,44,45 In spite of the active developments, significant radiosensitizing effects have not been proven in clinical trials until now. Therapeutics targeting the metabolic pathway of radioresistant CSCs such as DSF in this study could be another candidate with a unique treatment mechanism to enhance the effects of RT.

Although DSF has rare side effects on the nervous system such as mood or mental changes,46 specific adverse effects on the developing brain have not been reported. In this study, we focused on reducing drug concentration because there has been no information related to DSF in children. We also confirmed that in vivo DSF concentration is in the safety range when it is converted to human dose according to FDA guidelines.47 Although we have observed significant radiosensitizing effects even at low concentration, IC10, the safe application and effective dose of DSF in young patients need to be further defined. Altogether, this article demonstrates significant radiosensitizing effects of DSF in AT/RT and the radiosensitizing mechanisms of DSF. Because the DSF and RT combination treatment had significant in vivo therapeutic effects against AT/RT, concomitant chemoradiotherapy using DSF may be incorporated into conventional regimens for young AT/RT patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Neuro-Oncology online.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry fro Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (1420020) and the National Research Foundation of Korea(NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government(MSIP) (2016R1A5A2945889).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the reviewers and editors for their detailed analysis of our manuscript and their helpful comments and suggestions.

References

- 1. Burger PC, Yu IT, Tihan T, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the central nervous system: a highly malignant tumor of infancy and childhood frequently mistaken for medulloblastoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(9):1083–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Versteege I, Sévenet N, Lange J, et al. Truncating mutations of hSNF5/INI1 in aggressive paediatric cancer. Nature. 1998;394(6689):203–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Judkins AR, Burger PC, Hamilton RL, et al. INI1 protein expression distinguishes atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor from choroid plexus carcinoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64(5):391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Torchia J, Picard D, Lafay-Cousin L, et al. Molecular subgroups of atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumours in children: an integrated genomic and clinicopathological analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(5):569–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johann PD, Erkek S, Zapatka M, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors are comprised of three epigenetic subgroups with distinct enhancer landscapes. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(3):379–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hilden JM, Meerbaum S, Burger P, et al. Central nervous system atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor: results of therapy in children enrolled in a registry. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(14):2877–2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tekautz TM, Fuller CE, Blaney S, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors (ATRT): improved survival in children 3 years of age and older with radiation therapy and high-dose alkylator-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1491–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chi SN, Zimmerman MA, Yao X, et al. Intensive multimodality treatment for children with newly diagnosed CNS atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):385–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lafay-Cousin L, Hawkins C, Carret AS, et al. Central nervous system atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumours: the Canadian Paediatric Brain Tumour Consortium experience. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(3):353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee JY, Kim IK, Phi JH, et al. Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors: the need for more active therapeutic measures in younger patients. J Neurooncol. 2012;107(2):413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park ES, Sung KW, Baek HJ, et al. Tandem high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in young children with atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor of the central nervous system. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27(2):135–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choi SA, Choi JW, Wang KC, et al. Disulfiram modulates stemness and metabolism of brain tumor initiating cells in atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17(6):810–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hald J, Jacobsen E. A drug sensitizing the organism to ethyl alcohol. Lancet. 1948;2(6539):1001–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sauna ZE, Shukla S, Ambudkar SV. Disulfiram, an old drug with new potential therapeutic uses for human cancers and fungal infections. Mol Biosyst. 2005;1(2):127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Udaka YT, Shayan K, Chuang NA, Crawford JR. Atypical presentattion of atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor in a child. Case Rep Oncol Med. 2013;2013:815923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Choi SA, Wang KC, Phi JH, et al. A distinct subpopulation within CD133 positive brain tumor cells shares characteristics with endothelial progenitor cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;324(2):221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Franken NA, Rodermond HM, Stap J, Haveman J, van Bree C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(5):2315–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim S, Wu HG, Shin JH, Park HJ, Kim IA, Kim IH. Enhancement of radiation effects by flavopiridol in uterine cervix cancer cells. Cancer Res Treat. 2005;37(3):191–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choi SA, Lee YE, Kwak PA, et al. Clinically applicable human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells delivering therapeutic genes to brainstem gliomas. Cancer Gene Ther. 2015;22(6):302–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Choi SA, Lee JY, Phi JH, et al. Identification of brain tumour initiating cells using the stem cell marker aldehyde dehydrogenase. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(1):137–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hwang DW, Jin Y, Lee do H, et al. In vivo bioluminescence imaging for prolonged survival of transplanted human neural stem cells using 3D biocompatible scaffold in corticectomized rat model. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Szatmári T, Lumniczky K, Désaknai S, et al. Detailed characterization of the mouse glioma 261 tumor model for experimental glioblastoma therapy. Cancer Sci. 2006;97(6):546–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lumniczky K, Desaknai S, Mangel L, et al. Local tumor irradiation augments the antitumor effect of cytokine-producing autologous cancer cell vaccines in a murine glioma model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2002;9(1):44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Desaknai S, Lumniczky K, Esik O, Hamada H, Safrany G. Local tumour irradiation enhances the anti-tumour effect of a double-suicide gene therapy system in a murine glioma model. J Gene Med. 2003;5(5):377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bartelheim K, Nemes K, Seeringer A, et al. Improved 6-year overall survival in AT/RT—results of the registry study Rhabdoid 2007. Cancer Med. 2016;58(8):1765–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johansson B. A review of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of disulfiram and its metabolites. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1992; 369:15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barth KS, Malcolm RJ. Disulfiram: an old therapeutic with new applications. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9(1):5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hothi P, Martins TJ, Chen L, et al. High-throughput chemical screens identify disulfiram as an inhibitor of human glioblastoma stem cells. Oncotarget. 2012;3(10):1124–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lun X, Wells JC, Grinshtein N, et al. Disulfiram when combined with copper enhances the therapeutic effects of temozolomide for the treatment of glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3860–3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(9):741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baldwin AS. Regulation of cell death and autophagy by IKK and NF-κB: critical mechanisms in immune function and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2012;246(1):327–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pajonk F, Vlashi E, McBride WH. Radiation resistance of cancer stem cells: the 4 R’s of radiobiology revisited. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Singh SK, Clarke ID, Terasaki M, et al. Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res. 2003;63(18):5821–5828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Read TA, Fogarty MP, Markant SL, et al. Identification of CD15 as a marker for tumor-propagating cells in a mouse model of medulloblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(2):135–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Szumiel I. Ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress, epigenetic changes and genomic instability: the pivotal role of mitochondria. Int J Radiat Biol. 2015;91(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kelley K, Knisely J, Symons M, Ruggieri R. Radioresistance of brain tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(4):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yasui H, Asanuma T, Kino J, et al. The prospective application of a hypoxic radiosensitizer, doranidazole, to rat intracranial glioblastoma with blood brain barrier disruption. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kohshi K, Beppu T, Tanaka K, et al. Potential roles of hyperbaric oxygenation in the treatments of brain tumors. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2013;40(4):351–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carruthers R, Ahmed SU, Strathdee K, et al. Abrogation of radioresistance in glioblastoma stem-like cells by inhibition of ATM kinase. Mol Oncol. 2015;9(1):192–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith J, Tho LM, Xu N, Gillespie DA. The ATM-Chk2 and ATR-Chk1 pathways in DNA damage signaling and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 2010;108:73–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ahmed SU, Carruthers R, Gilmour L, Yildirim S, Watts C, Chalmers AJ. Selective inhibition of parallel DNA damage response pathways optimizes radiosensitization of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75(20):4416–4428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, et al. ; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(5):459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brassesco MS, Roberto GM, Morales AG, et al. Inhibition of NF- κ B by dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin suppresses invasion and synergistically potentiates temozolomide and γ-radiation cytotoxicity in glioblastoma cells. Chemother Res Pract. 2013;2013:593020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen D, Cui QC, Yang H, Dou QP. Disulfiram, a clinically used anti-alcoholism drug and copper-binding agent, induces apoptotic cell death in breast cancer cultures and xenografts via inhibition of the proteasome activity. Cancer Res. 2006;66(21):10425–10433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu P, Brown S, Goktug T, et al. Cytotoxic effect of disulfiram/copper on human glioblastoma cell lines and ALDH-positive cancer-stem-like cells. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(9):1488–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zimberg S. The clinical management of alcoholism.New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2016;7(2):27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.