Abstract

Background

Diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) remains challenging due to low sensitivity of CSF cytology and infrequent unequivocal MRI findings. In a previous pilot study, we showed that rare cell capture technology (RCCT) could be used to detect circulating tumor cells (CTC) in the CSF of patients with LM from epithelial tumors. To establish the diagnostic accuracy of CSF-CTC in the diagnosis of LM, we applied this technique in a distinct, larger cohort of patients.

Methods

In this institutional review board–approved prospective study, patients with epithelial tumors and clinical suspicion of LM underwent CSF-CTC evaluation and standard MRI and CSF cytology examination. CSF-CTC enumeration was performed through an FDA-approved epithelial cell adhesion molecule–based RCCT immunomagnetic platform. LM was defined by either positive CSF cytology or imaging positive for LM. ROC analysis was utilized to define an optimal cutoff for CSF-CTC enumeration.

Results

Ninety-five patients were enrolled (36 breast, 31 lung, 28 others). LM was diagnosed in 30 patients (32%) based on CSF cytology (n = 12), MRI findings (n = 2), or both (n = 16). CSF-CTC were detected in 43/95 samples (median 19.3 CSF-CTC/mL, range 0.3 to 66.7). Based on ROC analysis, 1 CSF-CTC/mL provided the best threshold to diagnose LM, achieving a sensitivity of 93%, specificity of 95%, positive predictive value 90%, and negative predictive value 97%.

Conclusions

We defined ≥1 CSF-CTC/mL as the optimal cutoff for diagnosis of LM. CSF-CTC enumeration through RCCT is a robust tool to diagnose LM and should be considered in the routine LM workup in solid tumor patients.

Keywords: cerebrospinal fluid, circulating tumor cells, leptomeningeal metastases

Importance of the study

Leptomeningeal metastasis is a devastating complication of cancer, and effective treatment depends on early and accurate diagnosis. However, current diagnostic tools comprising CSF cytology and MRI lack sensitivity. Repeated CSF and MRI examinations are often required and even then can yield false negative results. This prospective study of CSF-CTC was conducted in 95 patients with epithelial tumors and clinical suspicion of LM. We showed that 1 CSF-CTC/mL provides the optimal threshold to diagnose LM, yielding higher sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 95%. The addition of CSF-CTC evaluation to CSF cytology and MRI may enhance early diagnosis of LM and should be considered as part of routine LM workup.

Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) is a feared complication of cancer that carries an ominous prognosis. Early diagnosis coupled with vigorous treatment can improve neurological symptoms and prolong survival.1–3 However, establishing the diagnosis of LM based on standard cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytologic analysis or MRI findings is often difficult, particularly at early stages. Brain and spine MRIs have the advantage of being non-invasive, but their findings may be nonspecific and equivocal for LM. CSF cytology examination provides confirmation of LM but has low diagnostic sensitivity, often requiring multiple lumbar punctures to establish a diagnosis of LM.1,4,5 Hence, improved diagnostic tools that can accurately detect LM at an early stage are sorely needed.

Rare cell capture technology (RCCT) (Janssen Diagnostics) is an FDA-approved method for detecting and enumerating circulating tumor cells (CTC) in the blood of patients with epithelial tumors. It exploits an immunomagnetic enrichment platform and ferroparticles covered with anti–epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) antibody to capture EpCAM-expressing CTC.6 This method has been used to detect CTC in the blood of patients with metastatic carcinoma, and studies have shown correlations of CTC with tumor burden, treatment response, and prognosis.7–10

Previous studies demonstrated that RCCT can be used to detect CTC in the CSF of patients with established and newly diagnosed LM.11–13 In one study, CSF-CTC was enumerated in all 15 patients with LM; however, in one patient without definite LM, CSF-CTC was also detected, albeit at a low concentration of 0.27 CTC/mL.11 In order to further investigate the diagnostic accuracy of CSF-CTC in the diagnosis of LM and establish optimal cutoff values, we conducted a distinct, larger study in patients with epithelial tumors with symptoms suspicious for LM.

Methods

In this institutional review board–approved prospective study, we enrolled patients with epithelial tumors who presented with neurological symptoms suspicious for LM or had MRI findings suspicious for LM and were referred for clinical CSF examination from April 2013 to December 2015. All patients underwent MRI of the brain and/or spine and CSF cytology. All CSF was collected via a lumbar puncture. Standard CSF evaluation was performed, including CSF protein, glucose, white and red cell analysis, gram stain, bacterial and fungal cultures, and cytopathology analysis. In addition, 3 mL CSF from the same lumbar puncture was collected in a CellSave preservative tube and submitted for CSF-CTC analysis. We recorded patients’ demographics, cancer history and outcome, and presence of concurrent brain metastases.

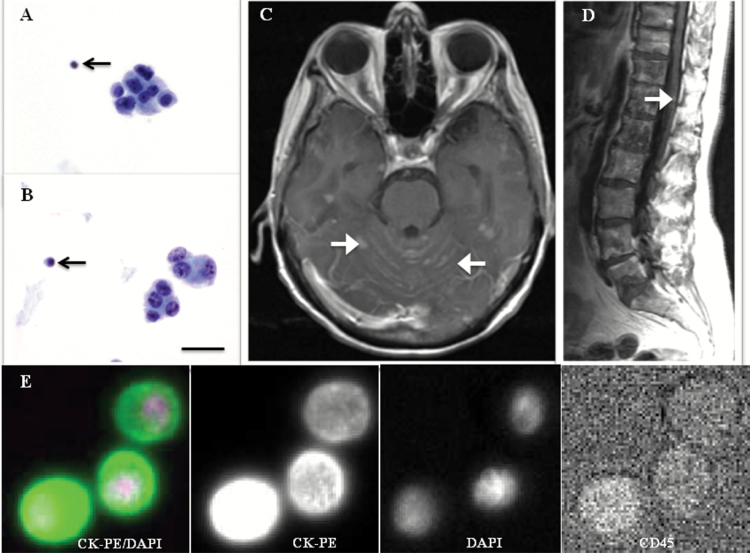

For this study, a composite definition of LM was based on positive CSF cytology (Fig. 1A and B) or unequivocal MRI findings (Fig. 1C and D) performed within a month of the CSF analysis. The one-month window was defined arbitrarily to ensure that the diagnosis of LM was new and relevant to the initial CSF-CTC result. Follow-up investigations for patients who had initial negative tests for LM were performed at the discretion of the patients’ treating oncologists. Unequivocal MRI findings were defined as leptomeningeal enhancement associated with subarachnoid nodules, basal cistern enhancement, or nerve root enhancement/clumping (Fig. 1C and D). Suspicious but equivocal MRI findings—such as multiple superficial parenchymal brain metastases at or near the sulci, intra- or periventricular masses, epidural metastases associated with dural enhancement, or new hydrocephalus—were not considered diagnostic of LM.

Fig. 1.

Definitions of LM in our study. (A and B) Micrographs of CSF cytology (magnification 100×; Papanicolaou stain) showing clustered tumor cells of large size and smaller lymphocytes (black arrows) for size comparison. Scale bar: 40 µm. (C) MRI brain and (D) MRI spine demonstrating leptomeningeal enhancement associated with subarachnoid nodules (white arrows), constituting an unequivocal MRI finding for LM. (E) Bottom row represents an example of a circulating tumor cell captured by RCCT, and is defined by positive epithelial cell marker (CK-PE) and nuclear dye (DAPI), negative leukocyte marker (CD45-allophycocyanin), and negative blank channel (not shown). Scale bar is irrelevant to row E.

The methodology for detection of CSF-CTC was described previously.11 Briefly, the CellSearch CTC Kit (Janssen Diagnostics) consists of EpCAM-bound antibody ferroparticles, fluorescent reagents (anti–cytokeratin phycoerythrin [CK-PE], 4ʹ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole [DAPI], and anti–cluster of differentiation [CD]45-allophycocyanin that stain for intracellular protein CK, cell nucleus, and leukocytes, respectively), CellTracks AutoPrep System, MagNest cell presentation device, and CellTracks Analyzer II. For each 3 mL of CSF sample, EpCAM-expressing cells were captured immunomagnetically before reagents were added. The CellTracks AutoPrep System dispensed 3.5 mL of reagent/sample mixture into a cartridge that was inserted into a MagNest device where magnetically labeled cells were pulled to the surface of the cartridge by a strong magnetic field. The CellTracks Analyzer II scanned the cartridge surface, acquired images, and displayed all events with both CK-PE and DAPI staining. Two experienced technicians reviewed the events independently and selected those that fulfilled criteria for CTC: EpCAM+, CK+, DAPI+, and CD45− (Fig. 1E). Results were reported as number of CTC/mL of CSF. Based on these definitions, we performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis to determine an optimal threshold value for CSF-CTC to diagnose LM.

Results

We enrolled 95 patients with epithelial tumors. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 58 years (range, 29–82 y); 70% were women. Breast and lung carcinoma were the most common primary tumors. Ninety-two patients presented with neurological symptoms suspicious for LM; the most common neurological symptom was headache, followed by gait instability and sensory abnormalities. The remaining 3 patients underwent CSF evaluation because they had MRI findings suspicious for LM (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 95)

| Patient Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Median age,* y (range) | 58 (29–82) |

| Gender, women (%) | 67 (71) |

| Primary cancer, N (%) | |

| Breast | 36 (38) |

| Lung | 31 (33) |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (7) |

| Renal | 5 (5) |

| Bladder | 5 (5) |

| Endometrial | 3 (3) |

| Ovarian | 2 (2) |

| Prostate | 2 (2) |

| Nasopharyngeal | 2 (2) |

| Thyroid | 1 (1) |

| Scalp (squamous cell carcinoma) | 1 (1) |

| CSF cytology,* N (%) | |

| Positive | 28 (29) |

| Negative | 67 (71) |

| MRI brain,* N (%) | |

| Positive for LM | 16 (17) |

| No evidence of LM | 77 (81) |

| Not performed | 2 (2) |

| MRI spine,* N (%) | |

| Positive for LM | 11 (11) |

| No evidence of LM | 69 (73) |

| Not performed | 15 (16) |

*At initial evaluation.

Table 2.

Clinical manifestations leading to initial evaluation for leptomeningeal metastases

| Clinical Manifestations Leading to Initial Evaluation for LM | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Clinical symptoms* | 92 (97) |

| Headache | 32 (34) |

| Gait instability | 28 (29) |

| Sensory changes | 24 (25) |

| Confusion/mental state changes | 22 (23) |

| Focal limb weakness | 22 (23) |

| Cranial nerves abnormalities | 16 (17) |

| Back pain | 9 (9) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 7 (7) |

| Seizures | 6 (6) |

| Urine incontinence | 4 (4) |

| Speech abnormalities | 3 (3) |

| MRI abnormalities | 3 (3) |

*Some patients had more than one clinical symptom.

LM was diagnosed in 30 (32%) patients at initial evaluation: 12 had positive CSF cytology, 2 had MRI findings positive for LM, and 16 had positive results from both CSF cytology and MRI. The remaining 65 patients had negative CSF cytology and negative or equivocal MRI and were therefore deemed to be negative for LM at the time of initial evaluation. At the initial lumbar puncture, CSF-CTC was detected in 43 (45%) patients with a median of 19.3 CSF-CTC/mL (range, 0.33–66.7); 29 of these patients fulfilled criteria for LM based on CSF cytology or MRI. Fourteen did not meet criteria for LM, 9 of whom had follow-up evaluation: 1 with CSF cytology and MRI and 8 with MRIs alone. None of these 9 patients developed definite LM. Three patients remained alive without any neurological signs more than a year from evaluation for LM, and 2 died from systemic cancer progression within 3 months from initial evaluation for LM (Supplementary Table).

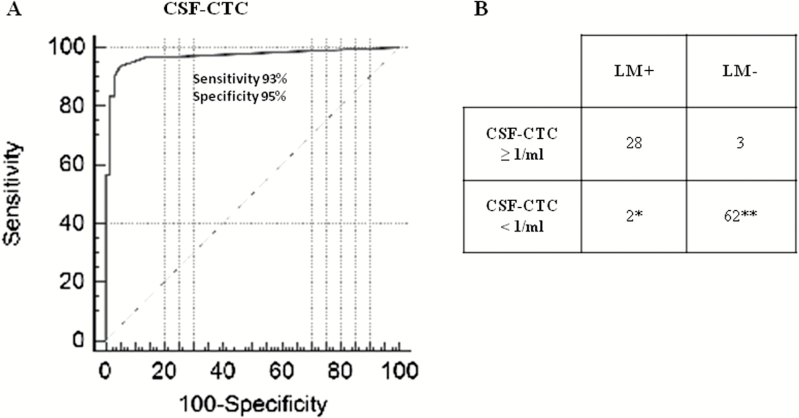

Using ROC analysis, a cutoff of ≥1 CSF-CTC/mL provided the best threshold to diagnose LM, achieving a sensitivity of 93% (95% CI, 84%–100%), specificity of 95% (95% CI, 90%–100%), positive predictive value (PPV) 90% (95% CI, 79%–100%), and negative predictive value (NPV) 97% (95% CI, 93%–100%) (Fig. 2A and B).

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic performance of CSF-CTC. (A) Area under the curve (AUC) and (B) 2 × 2 table demonstrating the sensitivity, specificity, and false positive and false negative rates of CSF-CTC using the optimal threshold of ≥1 CSF-CTC/mL. *2 patients with CTC of 0 and 0.66/mL. **51 patients with 0 CTC and 11 patients with 0.3–0.66 CSF-CTC/mL.

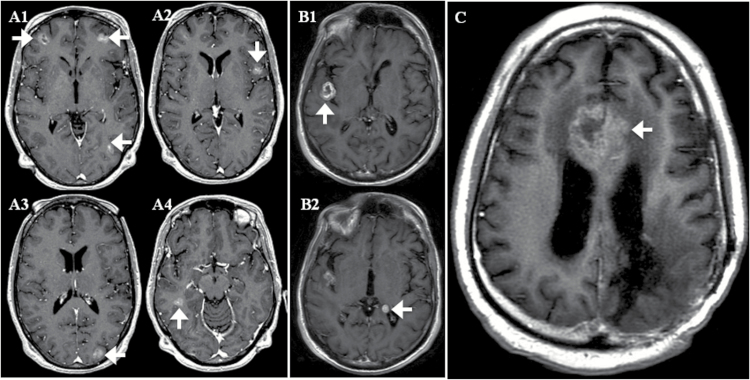

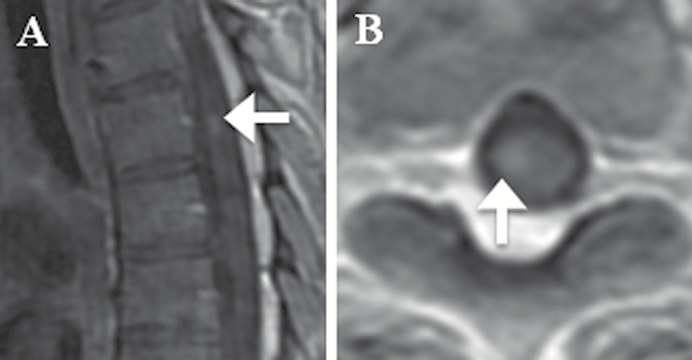

Applying this threshold, there were 3 patients who had one or more CSF-CTC/mL but did not meet study criteria for LM by standard diagnostic tests. All 3 patients had brain metastases at the sulci or next to the ventricles from underlying breast, lung, or bladder carcinoma (Fig. 3). For these 3 patients, follow-up MRIs performed between 27 and 78 days from the initial CSF evaluation remained negative for LM; none had repeat CSF cytology or autopsy. Conversely, 2 patients who were diagnosed with LM by our study criteria had <1 CSF-CTC/mL (Fig. 4). One patient had negative initial CSF cytology and was diagnosed with LM by MRI alone; the patient did not have follow-up CSF examination. The other diagnosis of LM was made in a patient by CSF cytology only.

Fig. 3.

MRIs of 3 patients with ≥1 CSF-CTC/mL but negative for LM by study criteria. Axial contrast T1-weighted images of patients (A1–4) and (B1–2) and (C) demonstrating brain parenchymal metastases in close proximity to CSF spaces at the sulci (white arrows) or ventricles (white arrowheads). The 3 patients with breast, bladder, and lung carcinomas had 1, 10, and 64 CSF-CTC/mL, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Patient’s MRI of diagnosed LM with <1 CSF-CTC/mL. (A) Sagittal and (B) axial contrast T1-weighted MRI spine of a patient with metastatic lung cancer demonstrating a nodular enhancement at the right ventral aspect of the spinal cord at T5 (white arrows). The patient had presented with progressive right lower extremity sensorimotor deficit and urinary retention, consistent with a spinal pathology.

In the 65 patients who had initial negative results for LM, 45 had follow-up tests with both CSF cytology and MRIs (n = 14), CSF cytology alone (n = 2), or MRIs alone (n = 29). Of these patients, 3 developed LM confirmed by CSF cytology at 2 months (n = 2) and 8 months (n = 1) after the initial CSF evaluation, but none of these 3 had detectable CSF-CTC at initial evaluation. Follow-up investigations remained negative in the remaining 42 patients.

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated CSF samples from 95 patients with epithelial tumors who had clinical symptoms suspicious for LM. ROC analysis showed that a threshold value of ≥1 CSF-CTC/mL provides high diagnostic sensitivity (93%) and specificity (95%), PPV 90% and NPV 97%, confirming CSF-CTC as a robust tool in diagnosing LM.

Over the years, several studies using various definitions for LM have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of CSF cytology and MRI.14–16 Collectively, these studies have shown that MRI performed better than CSF cytology, with sensitivity ranging from 76% to 100% compared with 46% to 75% for CSF cytology. CSF cytology is highly examiner dependent, relying on the experience of the pathologist and availability of immunostaining to identify specific cancer cell types. MRI achieved a higher sensitivity compared with CSF cytology in those studies but has limitations of interreader variability and nonspecific findings that are often indistinguishable from other CNS etiologies, such as infection and inflammatory changes. The overall suboptimal sensitivity of CSF cytology and specificity of MRI have prompted studies of other CSF biomarkers. However, while these studies showed that CSF biochemical markers, including cytokeratins, tumor markers, vascular endothelial growth factor, and neuron-specific enolase were often suggestive, they were rarely diagnostic of LM.17–21

Since the pilot study,11 other studies have sought to investigate tools that exploit the expression of the transmembrane glycoprotein EpCAM on carcinomas, thereby providing more direct measurements of tumor cells and eliminating the ambiguity associated with biochemical markers and MRI.22–25 The majority of studies included only patients with either breast or lung cancers or evaluated the utility of different EpCAM-based methods on the CSF.13,22–24 A recent study of an innovative approach utilizing flow cytometry immunophenotyping to identify EpCAM+ cells in the CSF demonstrated a higher sensitivity (80% vs 50%) but lower specificity (84% vs 100%) for LM diagnosis compared with CSF cytology.25 Another study of EpCAM-based flow cytometry showed 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity in relation to CSF cytology26; however, the study was limited by a sample size of only 13 patients with established and newly diagnosed LM.

In our study of the largest sample size of patients undergoing evaluation for clinical suspicious LM, CSF-CTC capture by EpCAM-based RCCT had high sensitivity and specificity, which may be attributed to the RCCT method of immunomagnetic enrichment and its ability to exclude EpCAM+ leukocytes. Only 3 patients negative for LM by our study criteria had ≥1 CSF-CTC/mL. All 3 patients had large brain parenchymal metastases that were close to the CSF compartments at the ventricles or sulci, which we postulate had resulted in shedding of tumor cells into the CSF that allowed identification of CSF-CTC in the absence of established LM. Conversely, 2 patients diagnosed with LM by our study criteria had <1 CSF-CTC/mL (0 CTC/mL and 0.66 CTC/mL). We postulate that the LM from these 2 patients, though not necessarily the primary tumors, had low expressing EpCAM below the threshold for detection. Unfortunately, none of the 4 patients with initial negative CSF cytology had follow-up CSF cytology or postmortem examinations that would have been helpful in clarifying their LM status.

The RCCT CellSearch platform is currently FDA approved for the isolation and enumeration of CTC from blood samples in patients with metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal carcinomas. Studies examining peripheral blood CTC have demonstrated its use as both a prognostic factor for survival and a biomarker of disease status. In patients with metastatic breast carcinoma, CTC levels equal to or greater than 5 CTC per 7.5 mL of whole blood were correlated with shorter median progression-free survival and median overall survival compared with patients with CTC levels lower than 5 per 7.5 mL of whole blood7; CTC levels were also correlated with radiographic progression of disease, demonstrating its potential use as a biomarker of treatment response.8 Similarly, baseline and changes in blood CTC numbers during treatment were correlated significantly with survival in men with progressive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer,10 while high blood CTC was significantly associated with high tumor burden27 and poor prognosis28,29 in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Future CSF-CTC studies should examine the role of CSF-CTC in prognostication and prediction of treatment response in patients with LM and include repeat CSF cytology and neuroimaging; if validated in other studies, CSF-CTC could potentially be incorporated into response criteria for LM.30

Our study has a number of limitations. EpCAM is an epithelial marker, and our results are only applicable to epithelial tumors, which nevertheless account for the vast majority of solid tumor patients with LM; marked loss of EpCAM expression in end-stage disease may potentially alter the performance of CSF-CTC determination. A low level contamination of epithelial cells from skin at the time of the lumbar puncture could theoretically contaminate the samples and lead to false positive results. Nonetheless, cytology review and the use of a threshold of ≥1 CTC/mL minimized this possibility. Second, LM diagnostic studies are inherently limited due to the lack of a reliable gold standard. We utilized the best methodologies currently used in clinical practice to diagnose LM, but they are associated with limited sensitivity and specificity. In addition, follow-up evaluations were based on clinical necessity and left at the discretion of treating physicians; they were not performed in a standardized manner and reflected the impracticality of mandating repeat lumbar punctures and MRIs for research purposes only, especially in the setting of end-stage cancer. This diminished our ability to ascertain whether a positive CSF-CTC in the absence of cytology or unequivocal MRI findings carried any diagnostic or prognostic significance, although enhanced clinical surveillance and repeat CSF analysis are likely warranted when any CSF CTC is found. Third, we only had a significant number of patients with breast or lung primaries; hence, we were unable to determine whether the utility of CSF-CTC varies among different epithelial primaries. Finally, CSF cytology in our study was more frequently positive in comparison to other studies, potentially reflecting the use of highly experienced cytologists with access to complementary immunohistochemistry tools to identify cancer cells in the CSF. It is possible that the information provided by the CSF-CTC will be even more useful at less experienced centers and facilities.

In summary, CSF-CTC capture and enumeration by RCCT is a novel, highly sensitive method to diagnose LM and constitutes a valuable tool to improve diagnostic performance of existing techniques. We have determined that 1 CSF CTC/mL or 3 or more CTC per 3 mL of the CSF is pathognomic and should be considered in all clinical evaluations. Collected in dedicated vials, the samples can be stored up to 3 days at room temperature, allowing for shipment to dedicated centers for analysis. Based on the findings of this study, the New York State Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment certification was granted for the use of the RCCT platform in enumerating CTC in CSF, and this assay is now routinely offered for CSF analysis at our institution.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at Neuro-Oncology online.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (P30-CA008748) and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Brain Tumor Center. Janssen Diagnostics provided reagents for the analysis but no financial support.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Judith Lampron for her editorial assistance. Part of this study was presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in Chicago, 2015, and World Federation of Neuro-Oncology Societies meeting at Zurich, 2017.

Conflict of interest statement. None.

References

- 1. Wasserstrom WR, Glass JP, Posner JB. Diagnosis and treatment of leptomeningeal metastases from solid tumors: experience with 90 patients. Cancer. 1982;49(4):759–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oechsle K, Lange-Brock V, Kruell A, Bokemeyer C, de Wit M. Prognostic factors and treatment options in patients with leptomeningeal metastases of different primary tumors: a retrospective analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136(11):1729–1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Riess JW, Nagpal S, Iv M et al. Prolonged survival of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in the modern treatment era. Clin Lung Cancer. 2014;15(3):202–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pauls S, Fischer AC, Brambs HJ, Fetscher S, Höche W, Bommer M. Use of magnetic resonance imaging to detect neoplastic meningitis: limited use in leukemia and lymphoma but convincing results in solid tumors. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(5):974–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Glantz MJ, Cole BF, Glantz LK et al. Cerebrospinal fluid cytology in patients with cancer: minimizing false-negative results. Cancer. 1998;82(4):733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Went PT, Lugli A, Meier S et al. Frequent EpCam protein expression in human carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(1):122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(8):781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu MC, Shields PG, Warren RD et al. Circulating tumor cells: a useful predictor of treatment efficacy in metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5153–5159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Allard WJ, Matera J, Miller MC et al. Tumor cells circulate in the peripheral blood of all major carcinomas but not in healthy subjects or patients with nonmalignant diseases. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(20):6897–6904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Scher HI, Jia X, de Bono JS et al. Circulating tumour cells as prognostic markers in progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: a reanalysis of IMMC38 trial data. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(3):233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nayak L, Fleisher M, Gonzalez-Espinoza R et al. Rare cell capture technology for the diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis in solid tumors. Neurology. 2013;80(17):1598–1605; discussion 1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patel AS, Allen JE, Dicker DT et al. Identification and enumeration of circulating tumor cells in the cerebrospinal fluid of breast cancer patients with central nervous system metastases. Oncotarget. 2011;2(10):752–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Le Rhun E, Massin F, Tu Q, Bonneterre J, Bittencourt Mde C, Faure GC. Development of a new method for identification and quantification in cerebrospinal fluid of malignant cells from breast carcinoma leptomeningeal metastasis. BMC Clin Pathol. 2012;12:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clarke JL, Perez HR, Jacks LM, Panageas KS, Deangelis LM. Leptomeningeal metastases in the MRI era. Neurology. 2010;74(18):1449–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freilich RJ, Krol G, DeAngelis LM. Neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid cytology in the diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis. Ann Neurol. 1995;38(1):51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Straathof CS, de Bruin HG, Dippel DW, Vecht CJ. The diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and cerebrospinal fluid cytology in leptomeningeal metastasis. J Neurol. 1999;246(9):810–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sölétormos G, Bach F. Cerebrospinal fluid cytokeratins for diagnosis of patients with central nervous system metastases from breast cancer. Clin Chem. 2001;47(5):948–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Corsini E, Bernardi G, Gaviani P et al. Intrathecal synthesis of tumor markers is a highly sensitive test in the diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis from solid cancers. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2009;47(7):874–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stockhammer G, Poewe W, Burgstaller S et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in CSF: a biological marker for carcinomatous meningitis. Neurology. 2000;54(8):1670–1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Herrlinger U, Wiendl H, Renninger M, Förschler H, Dichgans J, Weller M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in leptomeningeal metastasis: diagnostic and prognostic value. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(2):219–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang P, Piao Y, Zhang X, Li W, Hao X. The concentration of CYFRA 21-1, NSE and CEA in cerebro-spinal fluid can be useful indicators for diagnosis of meningeal carcinomatosis of lung cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2013;13(2):123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Magbanua MJ, Melisko M, Roy R et al. Molecular profiling of tumor cells in cerebrospinal fluid and matched primary tumors from metastatic breast cancer patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer Res. 2013;73(23):7134–7143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee JS, Melisko ME, Magbanua MJ et al. Detection of cerebrospinal fluid tumor cells and its clinical relevance in leptomeningeal metastasis of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;154(2):339–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tu Q, Wu X, Le Rhun E et al. CellSearch technology applied to the detection and quantification of tumor cells in CSF of patients with lung cancer leptomeningeal metastasis. Lung Cancer. 2015;90(2):352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Subirá D, Simó M, Illán J et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of flow cytometry immunophenotyping in patients with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2015;32(4):383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Milojkovic Kerklaan B, Pluim D, Bol M et al. EpCAM-based flow cytometry in cerebrospinal fluid greatly improves diagnostic accuracy of leptomeningeal metastases from epithelial tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(6): 855–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kaifi JT, Kunkel M, Dicker DT et al. Circulating tumor cell levels are elevated in colorectal cancer patients with high tumor burden in the liver. Cancer Biol Ther. 2015;16(5):690–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuboki Y, Matsusaka S, Minowa S et al. Circulating tumor cell (CTC) count and epithelial growth factor receptor expression on CTCs as biomarkers for cetuximab efficacy in advanced colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33(9):3905–3910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sastre J, Maestro ML, Gómez-España A et al. Circulating tumor cell count is a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab: a Spanish Cooperative Group for the Treatment of Digestive Tumors study. Oncologist. 2012;17(7):947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chamberlain M, Junck L, Brandsma D et al. Leptomeningeal metastases: a RANO proposal for response criteria. Neuro Oncol. 2016;pii: now183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.