Abstract

Background

Physical activity and exercise appear to improve sleep quality. However, the quantitative effects of Tai Chi on sleep quality in the adult population have rarely been examined. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the effects of Tai Chi on sleep quality in healthy adults and disease populations.

Methods

Medline, Cochrane Central databases, and review of references were searched through July 31, 2013. English-language studies of all designs evaluating Tai Chi’s effect on sleep outcomes in adults were examined. Data were extracted and verified by 2 reviewers. Extracted information included study setting and design, population characteristics, type and duration of interventions, outcomes, risk of bias and main results. Random effect models meta-analysis was used to assess the magnitude of treatment effect when at least 3 trials reported on the same sleep outcomes.

Results

Eleven studies (9 randomized and 2 non-randomized trials) totaling 994 subjects published between 2004 and 2012 were identified. All studies except one reported Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index. Nine randomized trials reported that 1.5 to 3 hour each week for a duration of 6 to 24 weeks of Tai Chi significantly improved sleep quality (Effect Size, 0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28 to 1.50), in community-dwelling healthy participants and in patients with chronic conditions. Improvement in health outcomes including physical performance, pain reduction, and psychological well-being occurred in the Tai Chi group compared with various controls.

Limitations

Studies were heterogeneous and some trials were lacking in methodological rigor.

Conclusions

Tai Chi significantly improved sleep quality in both healthy adults and patients with chronic health conditions, which suggests that Tai Chi may be considered as an alternative behavioral therapy in the treatment of insomnia. High-quality, well-controlled randomized trials are needed to better inform clinical decisions.

Keywords: Tai Chi, Sleep Quality, Quality of Life

Introduction

Adequate sleep is critical for optimum human functioning. Insomnia is a common sleep disorder affecting 30% of adults in the United States, with 10% having insomnia severe enough to cause daytime consequences [1]. Considerable evidence suggests that short-term sleep deprivation can negatively impact an individual’s alertness, mood, attention, and ability to concentrate [2], whereas long-term sleep deprivation is associated with chronic fatigue [3], obesity and diabetes [4–5], cardiovascular diseases [6], and increased mortality [7]. Recent large-scale cohort studies have established a relationship between sleep deprivation and mortality [7–8]. Poor or deprived sleep can result in increased workplace injuries and accidents, reduced work efficiency, poor employee physical and mental health, and an increased economic loss to the society [9–11]. Each year, insomnia associated with lost productivity in the workplace is estimated to cost 63.2 billion U.S. dollars [1].

Treatment approaches to improve sleep quality include both non-pharmacological strategies, such as modifying the sleep environment and improving sleep hygiene, as well as pharmacological strategies. Recent studies have started to explore the effects of mind-body therapies, such as Tai Chi, in addition to conventional treatment approaches to improve sleep quality in various populations.

Tai Chi originated in China as a martial art, focusing on the mind and body as an interconnected system, on breathing, and on keeping a calm state of mind with a goal toward deep states of relaxation. Recent evidence demonstrates the benefits of Tai Chi in treating chronic pain [12], psychological health [13], osteoarthritis [14–15], rheumatoid arthritis [16], Parkinson’s disease [17], cardiovascular health [18–19], and overall health related quality of life [20]. Tai Chi is becoming increasingly popular in many countries as a form of exercise to promote fitness and well-being. Insomnia may stem from somatized tension or anxiety, and therefore, Tai Chi practice may be a logical therapeutic approach for people seeking to improve their sleep quality. Nevertheless, convincing quantitative evidence to estimate treatment effects has been lacking. No meta-analysis addressing any sleep outcomes with Tai Chi has ever been published. To better inform patients and physicians, we systematically reviewed the quantitative relationship between Tai Chi and sleep quality by critically appraising and synthesizing the evidence from published English studies of healthy and chronically ill populations.

Methods

Data Sources and Study Selection

Medline and Cochrane Registry for Clinical Trials were searched until July 31, 2013 using the search terms for Tai Chi (“Tai Chi”, “Taijiquan”, “T’ai Chi Ch’uan”) and search terms for insomnia (“sleep”, “insomnia”, “Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index-PSQI”). Studies of all designs including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), clinical trials, and observational studies were deemed eligible. Bibliographies of reviews were perused to identify additional articles.

English language studies conducted in adults (≥ 18 years) with or without health problems were selected. Studies that examined any style of Tai Chi as an intervention compared to a control group were eligible. Sleep-related outcomes of interest included global measure and individual components of PSQI. The PSQI was originally designed for use in clinical populations as a simple and valid assessment of both sleep quality and sleep disturbance [21]. The seven components assessed with the PSQI questionnaire include: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. A global PSQI score greater than five has a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% in distinguishing good and poor sleepers [21]. Other outcomes of interest in this review include quality-of-life, cognitive performance, functional mobility, and pain.

Data Extraction and Study Quality Assessment

We screened abstracts and further examined full-text articles according to pre-specified eligibility criteria. Extracted data included information on study and participant characteristics, intervention and comparator characteristics (intensity, frequency, duration, and style of Tai Chi practice), follow-up, PSQI outcomes, and other sleep-related outcomes. Data about pain and quality-of-life were also extracted. One reviewer extracted data into structured forms that were reviewed by a second reviewer for completeness and accuracy. Risk of bias was graded using Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [22]. Individual items evaluating risk of bias included: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective outcome reporting.

Data Synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Quantitative meta-analysis was conducted when at least 3 trials provided comparative data on outcomes of interest. Data were synthesized at the end of the last follow-up. When calculating the standardized effect size (ES) for each study, a correlation of 0.50 was used between baseline and final values to account for repeated measurement within each study. The Hedges g value, the bias-corrected standardized mean difference, and the corresponding standard error were computed for each study. In view of significant heterogeneity, random-effect models were used for pooling. The overall mean ES was computed using a random-effects model that assumes the existence of no single true population effect and allows for random between-study variance in addition to sampling variability. The magnitude of the ES (clinical effects) indicates: (0–0.19) = negligible effect, (0.20–0.49) = small effect, (0.50–0.79) = moderate effect, (0.80+) = large effect. Included trials used the difference between the treatment and control group means. Heterogeneity was estimated with the I2 statistic and I2 >75% indicates significant heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity was also assessed using the Χ2 test. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version SE/11.2 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

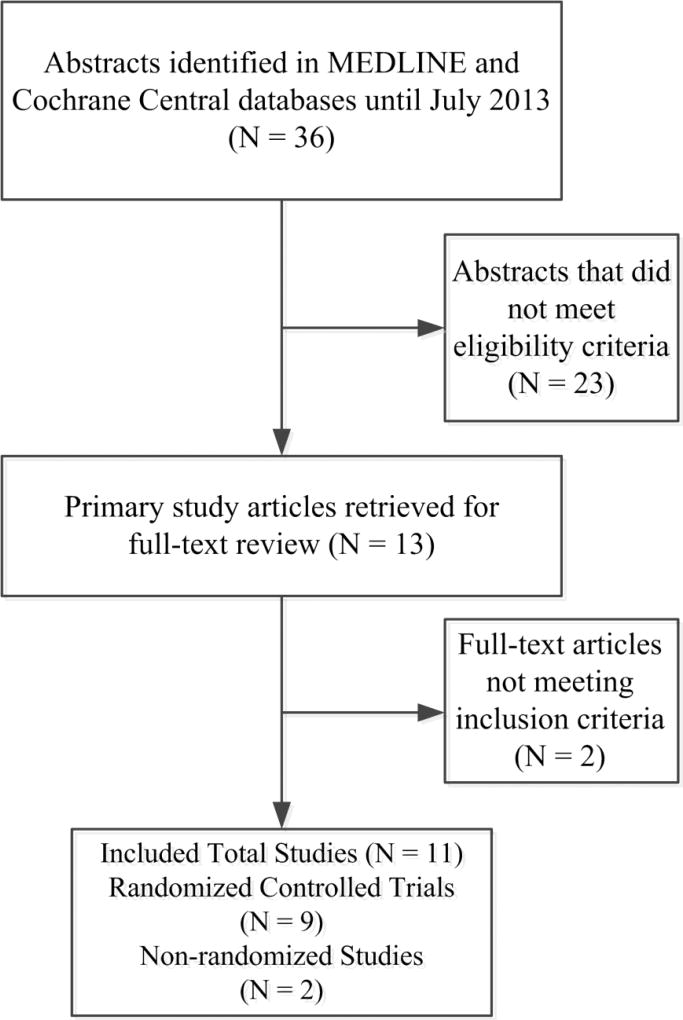

We reviewed 36 English language abstracts and retrieved 13 full-text articles for detailed evaluation (Figure 1). Two of 13 studies were eliminated for not reporting relevant sleep outcome data. Ultimately, 11 studies that included a total of 994 participants were identified for data abstraction and critical appraisal. We did not search for any unpublished and non-English literature.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

Table 1 describes the study design and number of studies and participants for sleep outcomes. Of the 11 studies, there were 9 RCTs, 2 non randomized comparative studies published between 2004 and 2012. They were conducted in 5 countries (USA, Spain, Japan, Vietnam, and Iran). Seven studies were conducted in the US. There were 632 healthy individuals (5 studies) and 362 patients with chronic conditions (6 studies) which included fibromyalgia (3 studies), heart failure (1 study), and cerebrovascular disorder (1 study). Mean age ranged from 21 to 77 years, and 58% of participants were female. Various controls were compared among the 9 RCTs, with 4 RCTs having multiple types of controls. Both non randomized comparative studies from the same US investigators used special recreation as controls among college students. Most studies employed subjective sleep measures, including the PSQI Scale and Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). Only one RCT reported collecting objective sleep measure of electrocardiogram (ECG)-derived estimation of cardiopulmonary coupling.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Randomized Controlled Trials and Observational Studies Examining Tai Chi and Sleep Outcomes

| Source Country |

Population Subjects (N) Women (%) |

Mean Age (yr) |

Intervention Duration (Follow-up) |

Intervention | Outcomes related to Sleep |

Additional Outcomes |

Main Conclusion (Effect of Tai Chi vs. Control) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tai Chi Frequency (Style) |

Control | |||||||

| RCTs | ||||||||

| Jones, 2012 USA | Fibromyalgia 101 93% | 54 | 12 wk (12 wk) | 1.5 hr, 2×/wk (Modified 8-form Yang style) | Education 1.5 hr, 2×/wk | PSQI | FIQ; BPI; Arthritis Self-efficacy questionnaire; balance; functional mobility | Improved sleep quality, FIQ, pain, arthritis self-efficacy, and functional mobility. |

| Wang, 2010 USA | Fibromyalgia 66 87% | 50 | 12 wk (24 wk) | 1 hr, 2×/wk (10-form Classic Yang style) | Education and stretch exercises 1hr, 2×/wk | PSQI | FIQ; Patient/Physician global assessment score; 6-min walk; BMI; SF-36; CES-D; CPSS; VAS | Improved sleep quality, FIQ, depression, pain and quality of life. |

| Calandre, 2009 Spain | Fibromyalgia 81 90% | 50 | 6 wk (18 wk) | 1 hr, 3×/wk (Pool-based) | Stretching of main body muscles in warm water | PSQI | FIQ; BDI; STAI; SF-12 | No significant differences between groups, but improved post-intervention scores for sleep and FIQ in Tai Chi group. |

| Wang, 2010 Japan | Elderly with cerebrovascular disorder 34 65% | 77 | 12 wk (12 wk) | 50 min, 1×/wk (Classical Yang style) | Non-resistance training and resistance training | PSQI | GHQ; P300 amplitude and latency (obtained by auditory stimulus system) | Improved sleep quality, general health, anxiety/insomnia, and severe depression. |

| Yeh, 2008 USA | Patients with heart failure 18 50% | 59 | 12 wk (12 wk) | 1 hr, 2×/wk (5-core Master ChengManCh’ing’s Yang style) plus instructional video | Pharmacological therapy, dietary and exercise counseling | Sleep (sleep spectrogram on ECG) | MLHFQ; 6-min walk-test; symptom-limited exercise test; BNP; peak VO2; catecholamine measurements | Improved sleep state, 6-min walk distance, and quality of life. |

| Nguyen, 2012 Vietnam | Older adults 96 50% | 69 | 24 wk (24 wk) | 1 hr, 2×/wk (24-form style) | Routine daily activity | PSQI | FES; TMT | Improved sleep quality, cognitive performance, and balance. |

| Irwin, 2008 USA | Older adults 112 63% | 70 | 16 wk (25 wk) | 40 min, 3×/wk (westernized and Standardized version of Tai Chi) | Health education (2 hr/wk) | PSQI | BDI (qualitative) | Improved sleep quality, especially in older adults. |

| Li, 2004 USA | Older adults with moderate sleep complaints 118 81% | 75 | 12 wk (24 wk) | 1 hr, 3×/wk (Simplified Yang style, 8-form Easy Tai Chi) | Low-impact exercise (1 hr, 3×/wk) | PSQI; ESS | Physical performance; SF-12 | Improved sleep quality, physical performance and health. |

| Hosseini, 2011 Iran | Older adult residents in nursing home 62 52% | 69 | 12 wk (12 wk) | Gradually increased from 5min/session to 25 min/session, 3×/wk (10-stage Tai Chi) | No exercise | PSQI | None | Improved sleep quality. |

| NRS | ||||||||

| Caldwell, 2011 USA | College students 208 37% | 21 | 15 wk (15 wk) | 50 min, 2×/wk (Chen-style) | Special recreation (2.5 hr×1×/wk or 1.25 hr×2×/wk) | PSQI | Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; Four Dimensional Mood Scale; Perceived Stresss Scale; Self-Regulatory Self-Efficacy Scale | Improved sleep quality, mindfulness, and mood, reduced perceived stress. |

| Caldwell, 2009 USA | College students 98 51% | 21 | 15 wk (15 wk) | 50 min, 2×/wk (Chen-style) | Special recreation or Pilates 50 min, 2×/wk | PSQI | Self-regulatory efficacy; Four Dimensional Mood Scale; Strength and Balance | A trend towards improvement in sleep quality, self-efficacy, and mood. |

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BNP = B-type Natriuretic Peptide, BPI = Brief Pain Inventory, CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression, CPSS = Chronic Pain Self-Efficacy Scale, ESS = Epworth Sleepiness Scale; FIQ = Fibromyalgia Improvement Questionnaire, FES = Falls Efficacy Scale, GHQ = General Health Questionnaire, MLHFQ = Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire, NRS = Non-randomized Studies, PSQI = Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index, RCT = Randomized Controlled Trial, TMT = Trail Making Test, SF = Short Form, VAS = Visual Analog Scale, wk = week

Table 2 qualitatively assesses methodology quality for 9 RCTs. Overall 4 of 9 RCTs were graded good, 1 moderate, and 4 poor quality. Specifically, 6 RCTs reported on randomization sequence generation; 3 described an appropriate allocation concealment method, 5 reported on blinding for outcome assessors. All nine RCTs described withdrawals and dropouts. Dropout rates were moderate with 4 RCTs reporting dropouts 15 to 22%, and that the remaining 5 RCTs reported attrition <15%. One non randomized comparative study reported high dropouts of 23%, while the other did not report data on attrition.

Table 2.

Risk of Bias in Randomized Controlled Trials

| Source | Random sequence generation |

Allocation concealment |

Blinding of participants and personnel |

Blinding of outcome assessment |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective outcome reporting |

Overall Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jones, 2012 | + | ? | + | + | + | + | + |

| Wang, 2010 (US) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Calandre, 2009 | + | ? | − | − | + | + | ? |

| Wang, 2010 (Japan) | − | ? | − | + | − | + | − |

| Yeh, 2008 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Nguyen, 2012 | − | ? | ? | ? | − | + | − |

| Irwin, 2008 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Li, 2004 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hosseini, 2011 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

+ = low risk of bias; − = high risk of bias; ? = unclear risk of bias

None of the studies reported any other physical activities and exercise other than Tai Chi during study intervention period.

Meta-analysis results

We included 8 of 9 RCTs that provided data on sleep quantitative measures that used the global score of PSQI in the meta-analysis. Figure 2 displays the overall effects of Tai Chi on PSQI. Below, we describe results for studies that provided data for meta-analysis and those excluded from meta-analysis.

Figure 2.

Effect of Tai Chi on Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index in Randomized Controlled Trials

Eight of 9 RCTs with 660 participants assessed the effects of Tai Chi on sleep quality in both healthy adults and disease populations using the PSQI questionnaire. We found statistically significant improvements in PSQI with Tai Chi intervention compared with various controls (Effect size, 0.89; 95 % CI, 0.28 to 1.50) (Figure 2), with an I2 of 92%. Additional outcome measures examined in RCTs included pain, stress, depression, anxiety and quality of life as well as physical function performance. Tai Chi was performed for between 12 and 24 weeks (25 to 90 minutes each session, 2 to 3 times per week).

One RCT with 18 participants did not report data on PSQI and therefore, was not included in the meta-analysis [26]. Using objective measures of sleep spectrogram on ECG, this remaining RCT conducted among participants with chronic heart failure showed significantly enhanced sleep stability, walk distance and quality of life after a 12 week Yang style Tai Chi intervention that involved a practice frequency of one hour, twice a week [26].

Two non-randomized comparative studies were not included in the meta-analysis due to lack of sufficient quantitative data, and the participants in these studies were healthy college students. These studies reported that a single 50 minutes, twice a week, Chen-style Tai Chi intervention significantly improved sleep quality in healthy college students [31–32].

Other Outcomes

RCTs varied considerably in the types of questionnaires used for evaluation of other outcomes including, pain, quality of life, and depression. Four RCTs reported sleep outcomes in detail, of which 3 RCTs reported improvement in sleep outcomes including sleep latency, sleep duration, and use of sleep medications [24, 28–29]; 1 RCT found no significant difference [25]. Additional improvements with Tai Chi intervention were observed for the outcome of pain [12, 23–24] and functional mobility in 5 RCTs [12, 23, 26–27, 29].

Results were mixed for the outcomes of cognitive ability, depression, and quality-of-life. Significant improvements in cognitive ability with Tai Chi occurred in healthy older adults [27]; however, no significant difference was observed between Tai Chi and control groups in patients with a cerebrovascular disorder [25]. Two RCTs found significant improvement in depression scores [12, 25], however 2 other RCTs found no significant difference between Tai Chi and control groups in depression scores [24, 28]. Five RCTs evaluated four different quality-of-life measures [12, 24–26, 29]. Notably, while the overall or physical functioning component of quality-of-life scores improved with Tai Chi intervention versus controls in all 5 RCTs, mental functioning scores showed no difference between groups in 2 RCTs [24, 29].

Tai Chi intervention in two non randomized studies showed improvements in outcomes of mood and perceived stress among healthy college students, but had no effect on strength and balance.

Discussion

Tai Chi, a form of low impact mind-body exercise, has spread worldwide over the past three decades. This meta-analysis strengthens a growing body of evidence and updates our previous investigations of the effects of Tai Chi on health outcomes in terms of improved sleep quality.

Specifically, 8 of the 9 RCTs from our quantitative meta-analysis and qualitative evidence synthesis reported that a Tai Chi practice “dose” of 1.5 to 3 hours each week significantly improves overall improvement of sleep quality and enhances functional ability in healthy older adults and patients with chronic conditions. While the subjects with illness may get more benefit than the healthy subjects, because only two RCTs reported data on healthy subjects, we were unable to distinguish significant effects between subjects with and without underlying diseases because only two RCTs reported data on. healthy subjects.

Our review is consistent with several other reviews of mind-body therapies for sleep. For example, Sarris and Byrne [33] explored the effects of complementary medicine on the treatment of insomnia. Their review [33] supported evidence that mind-body therapies (Tai Chi and yoga) and manual therapies (acupuncture and acupressure) improve sleep quality. Another review by Irwin, Cole, and Nicassio [34] showed similar robust improvements in sleep quality, sleep latency, and the ability to remain asleep with the use of cognitive-behavioral treatment, relaxation, and behavioral-only treatment in older adults. Indeed, Tai Chi may act in a similar way to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, in that it allows the patient to have a better mind-body connection.

With other forms of exercise, the mind-body connection or control is not always incorporated. For example, compared to a meta-analysis of the effect of exercise training (SMD=0.47, 95% CI 0.08–0.86) on improving sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems [35], our study shows that Tai Chi intervention has a better effect (SMD=0.89, 95% CI 0.28–1.50). Thus, it appears that Tai Chi has more advantages than regular exercise because of its mind-body attributes. Although the exact biological mechanisms remain unknown, Tai Chi, a multi-component therapy integrating physical, psychosocial, emotional, spiritual, and behavioral elements, may act through intermediate pathways (e.g., neuroendocrine, immune function, neurochemical, and analgesic) to improve health outcomes [36–37]. It has been hypothesized that mind-body therapies improve sleep outcomes by restoring the homeostatic balance of sympathetic/parasympathetic function by reducing sympathetic activity and stimulating the parasympathetic nervous system. In addition, by focusing on movement or body positioning through controlled breathing and quieting the mind, Tai Chi might stimulate the release of endogenous neurohormones or other health recovery mechanisms [38], and promote deep states of relaxation, thereby proving to be an effective strategy in the treatment of insomnia.

From our review and meta-analysis, we understand that Tai Chi has been useful in treating insomnia and improving sleep quality in both adults and the elderly population, in both healthy people and people with chronic medical problems, as well as in people from different countries. Insomnia causes many negative health and economic outcomes [1–11] and it is prevalent as both a solitary condition and as co-morbidity in a variety of other diseases. Therefore, it is important to explore an inexpensive and effective way, such as Tai Chi, to treat insomnia and to improve sleep quantity and quality in various populations.

There are several limitations to the available literature base examining the effect of Tai Chi on sleep quality. First, only English language published studies are included in this review. Studies published in other languages should be considered in the future for another systematic review and meta-analysis. Second, the parameters of the study population and intervention are widely variable. There are only 11 studies in this review and these studies vary markedly with regard to recruited populations, control groups, and outcome assessment. They also only examine a short duration of Tai Chi practice (6 to 24 weeks), and as a result the long-term effect of Tai Chi intervention needs to be explored in the future. The eligible studies also include small sample sizes and some of the studies lack a sufficient follow-up period. Third, there are methodology limitations in the reviewed studies, including, lack of allocation concealment and lack of blinding. Fourth, very little information is available on whether mind-body therapies promote objective measures of healthy sleep. For example, none of the studies presented information on objective evaluation of polysomnography in participants.

Even though most of the studies have scientific rigor to support the positive effect of Tai Chi on improving sleep quality, we found that there was a mild to moderate dropout rate from each study. Therefore, we suggest that prior to considering Tai Chi as a treatment option, clinicians discuss with their patients that Tai Chi practice requires discipline and perseverance to achieve the desired outcomes. This is exemplified by the duration and frequency of practice in all eleven studies, which usually require practicing Tai Chi for approximately an hour, two or three times a week and continuing this practice for 12 to 24 weeks. As is the essence of many behavioral therapies, Tai Chi may have profound salutogenic effects on improving sleep quality, and these effects come only with consistent practice.

In conclusion, evidence accrued from 11 clinical trials indicates that Tai Chi appears to be an effective behavioral therapy to treat insomnia and improve sleep quality among healthy subjects and patients with chronic conditions. Future high-quality, well-controlled, longer duration RCTs are needed to better inform clinical decisions about using Tai Chi to treat insomnia and improve sleep quality.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the National Institutes of Health for Dr. Wang

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Coulouvrat C, Hajak G, Roth T, et al. Insomnia and the performance of US workers: Results from the America Insomnia Survey. Sleep. 2011;34(9):1161–1171. doi: 10.5665/SLEEP.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wehrens SM, Hampton SM, Kerkhofs M, Skene DJ. Mood, alertness, and performance in response to sleep deprivation and recovery sleep in experienced shiftworkers versus non-shiftworkers. Chronobiol Inter. 2012;29(5):537–548. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2012.675258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher C. Hospital RNs’ job satisfactions and dissatisfactions. J Nurs Admin. 2001;31(6):324–331. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200106000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buscemi D, Kumar A, Nugent R, Nugent K. Short sleep times predict obesity in internal medicine clinic patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(7):681–688. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yaggi HK, Araujo AB, McKinlay JB. Sleep duration as a risk factor for the development of Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):657–661. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullington JM, Haack M, Toth M, Serrador JM, Meier-Ewert HK. Cardiovascular, inflammatory, and metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation. Prog Cardiovas Dis. 2009;51(4):294–302. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Arch General Psychiatry. 2002;59(2):131–136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel SR, Ayas NT, Malhotra MR, White DP, Schernhammer ES, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and mortality risk in women. Sleep. 2004;27(3):440–444. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger AM, Hobbs BB. Impact of shift work on the health and safety of nurses and patients. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2006;10(4):465–471. doi: 10.1188/06.CJON.465-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leger D, Massuel MA, Metlaine A SISYPHE Study Group. Professional correlates of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29(2):171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roth T, Jaeger S, Jin R, Kalsekar A, Stang PE, et al. Sleep problems, comorbid mental disorders, and role functioning in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C, Schmid CH, Rones R, Kalish R, Yinh J, et al. A randomized trial of Tai Chi for fibromyalgia. New Engl J Med. 2010;363:743–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang C, Bannuru R, Ramel J, Kupelnick B, Scott T, et al. Tai Chi on psychological well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Comple Alter Med. 2010;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Schmid CH, Hibberd PL, Kalish R, Roubenoff R, et al. Tai Chi for treating knee osteoarthritis: designing a long-term follow up randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2008;9:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Schmid CH, Hibberd PL, Kalish R, Roubenoff R, et al. Tai Chi is effective in treating knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(11):1545–1553. doi: 10.1002/art.24832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C. Tai Chi improves pain and functional status in adults with rheumatoid arthritis: results of a pilot single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Med Sport Sci. 2008;52:218–229. doi: 10.1159/000134302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, Eckstrom E, Stock R, et al. Tai Chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:511–519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeh GY, Wang C, Wayne PM, Phillips R. Tai chi exercise for patients with cardiovascular conditions and risk factors: a systematic review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29(3):152–60. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181a33379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeh GY, McCarthy EP, Wayne PM, Stevenson LW, Wood MJ, et al. Tai chi exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(8):750–757. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blake H, Hawley H. Effects of Tai Chi exercise on physical and psychological health of older people. Curr Aging Sci. 2012;5(1):19–27. doi: 10.2174/1874609811205010019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, III, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones KD, Sherman CA, Mist SD, Carson JW, Bennett RM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of 8-form Tai Chi improves symptoms and functional mobility in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:1205–1214. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-1996-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calandre EP, Rodriguez-Claro ML, Rico-Villademoros F, Vilchez JS, Hidalgo J, et al. Effects of pool-based exercise in fibromyalgia symptomatology and sleep quality: a prospective randomized comparison between stretching and Tai Chi. Clin exp rheumatol. 2009;27(5, Suppl 56):S21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W, Sawada M, Noriyama Y, Arita K, Ota T, et al. Tai Chi exercise versus rehabilitation for the elderly with cerebral vascular disorder: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Psychogeriatrics. 2010;10:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2010.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeh GY, Mietus JE, Peng CK, Phillips RS, Davis RB, et al. Enhancement of sleep stability with Tai Chi exercise in chronic heart failure: preliminary findings using an ECG-based spectrogram method. Sleep Med. 2008;9(5):527–536. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen MH, Kruse A. A randomized controlled trial of Tai chi for balance, sleep quality and cognitive performance in elderly Vietnamese. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:185–190. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S32600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Motivala SJ. Improving sleep quality in older adults with moderate sleep complaints: a randomized controlled trial of Tai Chi Chih. Sleep. 2008;31(7):1001–1008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li F, Fisher KJ, Harmer P, Irbe D, Tearse RG, et al. Tai Chi and self-rated quality of sleep and daytime sleepiness in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:892–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosseini H, Esfirizi MF, Marandi SM, Rezaei A. The effect of Ti Chi exercise on the sleep quality of the elderly residents in Isfahan, Sadeghieh elderly home. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2011;16(1):55–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caldwell K, Emery L, Harrison M, Greeson J. Changes in mindfulness, well-being, and sleep quality in college students through Taijiquan courses: a cohort control study. J Alter and Comple Med. 2011;17(10):931–938. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caldwell K, Harrison M, Adams M, Triplett T. Effect of pilates and taiji quan training on self-efficacy, sleep quality, mood, and physical performance of college students. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2009;13:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarris J, Byrne GJ. A systematic review of insomnia and complementary medicine. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irwin MR, Cole JC, Nicassio PM. Comparative meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for insomnia and their efficacy in middle-aged adults and in older adults 55 years of age. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):3–14. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Pei-Yu, Ho Ka-Hou, Chen Hsi-Chung, Chien Meng-Yueh. Exercise training improves sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems: a systematic review. J Physiothe. 2012;58:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70106-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, et al. Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:564–70. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000077505.67574.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Oxman MN. Augmenting immune responses to varicella zoster virus in older adults: a randomized, controlled trial of Tai Chi. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:511–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jahnke R, Larkey L, Rogers C, Etnier J, Lin F. A comprehensive review of health benefits of Qigong and Tai Chi. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24(6):e1–e25. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.081013-LIT-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]