Abstract

The overuse of medical services is an increasingly recognized driver of poor quality care and high cost. A practical framework is needed to guide clinical decisions and facilitate concrete actions that can reduce overuse and improve care. We used an iterative, expert-informed evidence-based process to develop a framework for conceptualizing interventions to reduce medical overuse.

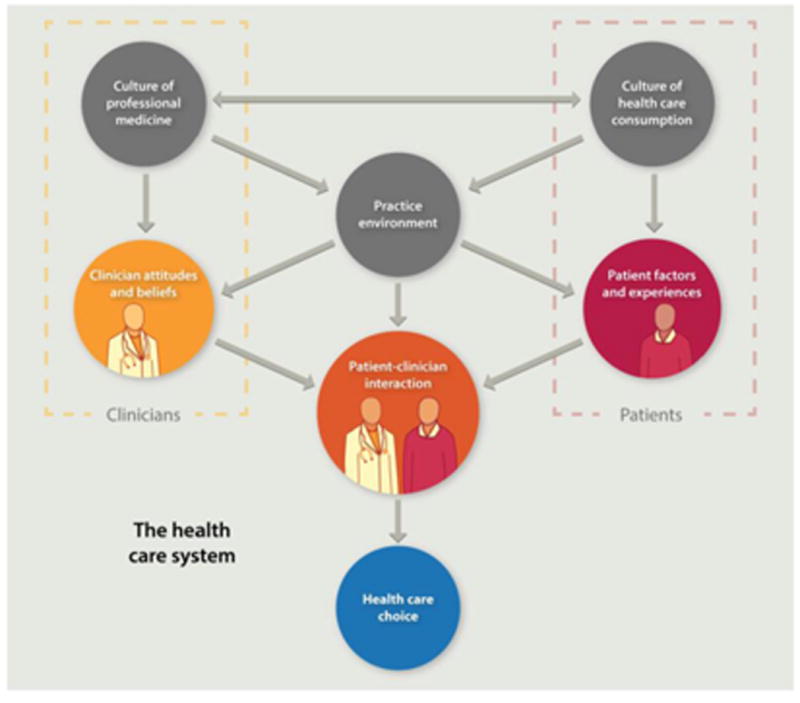

Given the complexity of defining and identifying overused care in nuanced clinical situations and the need to define care appropriateness in the context of an individual patient, this framework conceptualizes the patient-clinician interaction as the nexus of decisions regarding inappropriate care. Other drivers of utilization influence this interaction and include health care system factors, the practice environment, the culture of professional medicine, the culture of health care consumption, and individual patient and clinician factors. The variable strength of evidence in support of these domains highlights important areas for further investigation.

Keywords: High value care, Patient-centered care, Quality Improvement, Overuse, Conceptual framework

Introduction

Medical overuse is the provision of healthcare services for which there is no medical basis or for which harms equal or exceed benefits. 1 It drives poor quality care and unnecessary cost. 2, 3 The high prevalence of overuse is recognized by patients,4 clinicians,5 and policymakers6; initiatives to reduce overuse have been launched, targeting physicians,7 the public, 8 and medical educators9, 10 with limited impact.11, 12 To date, few studies have addressed methods to reduce overuse, and de-implementing non-beneficial practices has proven challenging. 1, 13, 14 Existing conceptual models for reducing overuse are theoretical15 or focused at administrative decisions16, 17; we believe a practical framework is needed. We used an iterative process, informed by expert opinion and discussion, to design such a framework.

Methods

First the four authors, who have expertise in overuse, value, medical education, evidence-based medicine and implementation science, reviewed related conceptual frameworks 18 and evidence regarding drivers of overuse. We organized these drivers into domains to create a draft framework which we presented at Preventing Overdiagnosis 2015, a meeting of clinicians, patients and policy makers with interest in overuse. We incorporated feedback from meeting attendees to modify framework domains, and performed structured searches using keywords in PubMed to explore evidence in support of items within each domain and estimate its strength. We rated supporting evidence as strong (studies demonstrate a clear correlation between a factor and overuse), moderate (evidence suggests such a correlation or demonstrates a correlation between a particular factor and utilization but not overuse per se), weak (only indirect evidence exists), or absent (no studies identified evaluating a particular factor). All authors reached consensus on ratings.

Framework principles and evidence

A patient-centered definition of overuse

During framework development, defining clinical appropriateness emerged as the primary challenge to identifying and reducing overuse. While some care generally is appropriate based on strong evidence of benefit and some is inappropriate due to clear lack of benefit or harm, much care is of unclear or variable benefit. Practice guidelines can help identify overuse, but their utility may be limited by lack of evidence in specific clinical situations19 and their recommendations may apply poorly to an individual patient. This presents challenges to using guidelines to identify and reduce overuse.

Despite limitations, the scope of overuse has been estimated by applying broad, often guideline-based, criteria for care appropriateness to administrative data.20 Unfortunately, these estimates provide little direction to clinicians and patients partnering to make usage decisions. During framework development we identified the importance of a patient-level, patient-specific definition of overuse. This approach reinforces the importance of meeting patient needs while standardizing treatments to reduce overuse. A patient-centered approach may also assist professional societies and advocacy groups in developing actionable campaigns and may uncover evidence gaps.

The centrality of the patient-clinician interaction

During framework development, the patient-clinician interaction emerged as the nexus through which drivers of overuse exert influence. The centrality of this interaction is demonstrated in studies of the relationship between care continuity and overuse21 or utilization 22, 23, by evidence that communication and patient-clinician relationships impact utilization,24 and by the observation that clinician training in shared decision-making reduces overuse.25 A patient-centered framework assumes that, at least when weighing clinically reasonable options, a patient-centered approach will optimize outcomes for that patient.

Incorporating drivers of overuse

We incorporated drivers of overuse into domains and related them to the patient-clinician interaction. 26Domains included the culture of healthcare consumption, patient factors and experiences, the practice environment, the culture of professional medicine, and clinician attitudes and beliefs.

We characterized the evidence illustrating how drivers within each domain influence healthcare use. The evidence for each domain is described in Table 1.

Table 1. Factors that contribute to each domain of the framework for overuse of care.

| Domain | Factors | Evidence | Specific impact | Likely magnitude of effect on overuse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture of health care consumption |

|

Strength: weak None related to specific factors Evidence related to: |

Likely leads to more general utilization, overuse, and use of costlier alternatives | Moderate |

| Patient factors and experiences |

|

Strength: weak to strong Evidence related to: |

Variable; can contribute to overuse or protect against overuse | Moderate. Interventions related to with patient demographics not defined |

| Culture of professional medicine |

|

Strength: absent to moderate No evidence exploring role of most individual factors Evidence related to: |

Overuse performance measures can limit overuse but measures for preventing underuse may lead to overuse Emphasis on certainty, technology and active intervention likely contribute to overuse |

Moderate to high |

| Clinician attitudes and beliefs |

|

Strength: weak Evidence related to: |

Traditionally mostly push toward more care Poor numeracy, lack of knowledge, discomfort with uncertainty, sampling biases from past experiences, interactions with other clinicians, fear of litigation, and some personality traits likely lead to overuse Patient continuity helps prevent overuse |

High |

| Practice environment |

|

Strength: weak Practice norms not well studied Evidence related to: |

Local cultural norms are influential (including local training culture) Other factors vary based on specifics |

High |

| The patient-clinician interaction |

|

Strength: moderate for shared decision making, continuity, weak for other factors Evidence related to: |

Continuity of care likely reduces overuse Shared decision making likely reduces overuse Unclear impact of culture and language |

High |

Note: Likely magnitude of effect on overuse was determined by author consensus based on strength and breadth of evidence and other factors

Results

The final framework is shown in the Figure. Within the healthcare system, patients are influenced by the culture of healthcare consumption, which varies within and among countries.27 Clinicians are influenced by the culture of medical care, which varies by practice setting28, and by their training environment.29 Both clinicians and patients are influenced by the practice environment and by personal experiences. Ultimately, clinical decisions occur within the specific patient-clinician interaction.24 Table 1 describes components of each domain, the domain's likely impact on overuse, and the estimated strength of supporting evidence. Interventions can be conceptualized within appropriate domains or through the interaction between patient and clinician.

Figure. Framework for understanding and reducing overuse.

Discussion

We developed a novel and practical conceptual framework for characterizing drivers of overuse and potential intervention points. To our knowledge, this is the first framework incorporating a patient-specific approach to overuse and emphasizing the patient-clinician interaction. Key strengths of framework development are the inclusion of a range of perspectives and the characterization of the evidence within each domain. Limitations include the fact that we did not perform a formal systematic review and our broad, qualitative assessments of the strength of evidence. However, we believe this framework provides an important conceptual foundation for future study of overuse and interventions to reduce it.

Framework applications

The framework highlights the many drivers of overuse; it can facilitate understanding of overuse and help conceptualize change, prioritize research goals, and inform specific interventions. For policymakers, the framework can inform efforts to reduce overuse by emphasizing the need for complex interventions and by clarifying the likely impact of interventions targeting specific domains. Similarly, for clinicians and quality improvement professionals the framework can ground root cause analyses of overuse-related problems and inform allocation of limited resources. Finally, the relatively weak evidence informing the role of most acknowledged drivers of overuse suggests an important research agenda. Specifically, defining relevant physician and patient cultural factors, investigating interventions to impact culture, defining features of the practice environment that optimize care appropriateness, and describing specific practices during the patient-clinician interaction that minimize overuse (while providing needed care) are pressing needs.

Targeting interventions

Domains within the framework are influenced by different types of interventions, and different stakeholders may target different domains. For example:

The culture of health care consumption may be influenced through public education (e.g. Choosing Wisely® patient resources)30-32, and public health campaigns.

The practice environment may be influenced by initiatives to align clinician incentives,33 team care,34 electronic health record interventions35, and improving access.36

Clinician attitudes and beliefs may be influenced by audit and feedback, 37-40 reflection41 role-modeling,42 and education.43-45

Patient attitudes and beliefs may be influenced by education, access to price and quality information, and increased engagement in care. 46, 47

For clinicians, the clinician-patient interaction can be improved through training in communication and shared-decision-making,25 access to information (e.g. costs) that can be easily shared with patients48, 49, and novel visit structures (e.g. scribes).50

On the patient side, the interaction may be optimized through improved access (e.g. through telemedicine) 51, 52 or patient empowerment during hospitalization.

The culture of medicine is difficult to influence. Change is likely to occur through regulatory intervention (e.g. CMMI's Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative), educational initiatives (e.g. AAIM/ACP high-value care curricula53) and medical journal features (e.g. “Less is More” from JAMA Internal Medicine54, “Things We Do for No Reason” from the Journal of Hospital Medicine) and professional organizations (e.g. Choosing Wisely®).

As organizations implement quality improvement initiatives to reduce overused services, the framework can be used to target interventions to relevant domains. For example, a hospital leader who wishes to reduce opioid prescribing may use the framework to identify the factors encouraging prescribing in each domain, including poor understanding of pain treatment (a clinician factor), desired early discharge encouraging overly aggressive pain management (an environmental factor), patient demand for opioids with poor understanding of harms (patient factors), and poor communication around pain (a patient-clinician interaction factor). While not all relevant factors can be addressed, their classification by domain facilitates intervention, in this case perhaps leading to a focus on clinician and patient education about opioids and development of a practical communication tool, targeting 3 domains. Table 2 provides examples of how the framework informs approaches to this and other overused services in the hospital setting. Note that some drivers can be acknowledged without identifying targeted interventions.

Table 2. Using the framework for real life examples of overuse to identify practical ways in which overuse can be addressed.

| Example of overuse | Possible drivers/domains | Feasible approaches to improvement |

|---|---|---|

| A hospitalist on a general medical service wants to reduce use of routine lab testing |

Culture of health care: expectation of all clinicians (including attendings, consultants, nursing) for daily lab testing Clinician factors: belief that more is better, poor knowledge of evidence Practice environment: ease of daily ordering in the EMR Patient factors: expectation for frequent testing (likely a minor factor) |

Culture: broad campaign across the medical center Clinician: education about evidence/guidelines43,44 Practice environment: EMR alert35 |

| A physician hospital leader wishes to reduce inpatient opioid prescribing |

Clinician factors: misperception of patient/parent desires, discomfort with pain treatment81 Practice environment: pressure to discharge patients leading to aggressive pain treatment Patient factors: poor understanding of the potential harms of opioids, demand Patient-clinician interaction: poor communication regarding pain itself and the benefits/harms of therapy |

Clinician: education about guidelines/evidence43,44 Patient: provide information about options for treating pain and potential opioid harms Patient-clinician interaction: physician-directed tool for communicating about the issue49 |

| A palliative care fellow seeks to reduce imaging tests in end-of-life (EOL) hospitalized patients |

Culture of health care: need to define clinical problems even if there is no intervention, discomfort with doing nothing Clinician factors: belief that more information helps patients, belief that patients desire testing Patient factors: poor knowledge or acceptance of prognosis Patient-clinician interaction: poor communication regarding prognosis and EOL preferences |

Clinician factors: education about harms of testing in these patients Patient-clinician interaction: specific tools to improve communication about EOL preferences49,78 |

EMR = electronic medical record; CMO=Chief Medical Officer

Moving forward

Through a multi-stakeholder iterative process, we developed a practical framework for understanding medical overuse and interventions to reduce it. Centered on the patient-clinician interaction, this framework explains overuse as the product of medical and patient culture, the practice environment and incentives, and other clinician and patient factors. Ultimately, care is implemented during the patient-clinician interaction, though few interventions to reduce overuse have focused on that domain.

Conceptualizing overuse through the patient-clinician interaction maintains focus on patients while promoting better and lower-cost population health. This framework can guide interventions to reduce overuse at important parts of the health care system while ensuring the final goal of individualized high quality patient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Valerie Pocus for help with the artistic design of the Framework; no other non-authors contributed to the manuscript. An early version of the Framework was presented at the 2015 Preventing Overdiagnosis meeting in Bethesda, MD.

Disclosure of funding sources: DJM received research support from the VA Health Services Research (CRE 12-307), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (K08- HS18111). AL's work was supported by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). DK's work on this paper was supported by a Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (award number P30 CA008748).

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: DJM has provided a self-developed lecture in a 3M sponsored series on hospital epidemiology and received honoraria for serving as a book and journal editor from Springer Publishing. CDS is employed by the American College of Physicians. She owns stock in Merck and Co where her husband is employed. The other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Morgan DJ, Brownlee S, Leppin AL, et al. Setting a research agenda for medical overuse. BMJ. 2015;351:h4534. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hood VL, Weinberger SE. High value, cost-conscious care: an international imperative. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(6):495–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korenstein D, Falk R, Howell EA, Bishop T, Keyhani S. Overuse of health care services in the United States: an understudied problem. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(2):171–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.How S, Shih A, Lau J, Schoen C. Public Views on US Health System Organization: A Call for New Directions. The Commonwealth Fund; Aug, 2008. [Accessed 11 December 2015]. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/data-briefs/2008/aug/public-views-on-u-s--health-system-organization--a-call-for-new-directions. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sirovich BE, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Too Little? Too Much? Primary care physicians' views on US health care: a brief report. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(17):1582–5. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Joint Commission and the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement. [Accessed 8 July 2016];Proceedings from the National Summit on Overuse. 2012 Sep 24; Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/National_Summit_Overuse.pdf.

- 7.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfson D, Santa J, Slass L. Engaging physicians and consumers in conversations about treatment overuse and waste: a short history of the choosing wisely campaign. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):990–5. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith CD, Levinson WS. A commitment to high-value care education from the internal medicine community. Ann Int Med. 2015;162(9):639–40. doi: 10.7326/M14-2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korenstein D, Kale M, Levinson W. Teaching value in academic environments: shifting the ivory tower. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1671–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kale MS, Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Trends in the overuse of ambulatory health care services in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):142–8. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early Trends Among Seven Recommendations From the Choosing Wisely Campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prasad V, Ioannidis JP. Evidence-based de-implementation for contradicted, unproven, and aspiring healthcare practices. Implement Sci. 2014;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ubel PA, Asch DA. Creating value in health by understanding and overcoming resistance to de-innovation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(2):239–44. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell AA, Bloomfield HE, Burgess DJ, Wilt TJ, Partin MR. A conceptual framework for understanding and reducing overuse by primary care providers. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(5):451–72. doi: 10.1177/1077558713496166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nassery N, Segal JB, Chang E, Bridges JF. Systematic overuse of healthcare services: a conceptual model. Appl Health Econ Helath Policy. 2015;13(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s40258-014-0126-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segal JB, Nassery N, Chang HY, Chang E, Chan K, Bridges JF. An index for measuring overuse of health care resources with Medicare claims. Med Care. 2015;53(3):230–6. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reschovsky JD, Rich EC, Lake TK. Factors Contributing to Variations in Physicians' Use of Evidence at The Point of Care: A Conceptual Model. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(Suppl 3):S555–61. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3366-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feinstein AR, Horwitz RI. Problems in the “evidence” of “evidence-based medicine”. Am J Med. 1997;103(6):529–35. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Makarov DV, Soulos PR, Gold HT, et al. Regional-Level Correlations in Inappropriate Imaging Rates for Prostate and Breast Cancers: Potential Implications for the Choosing Wisely Campaign. JAMA Onc. 2015;1(2):185–94. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romano MJ, Segal JB, Pollack CE. The Association Between Continuity of Care and the Overuse of Medical Procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1148–54. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Shoup JA, Zeng C, McQuillan DB, Steiner JF. Effect of continuity of care on hospital utilization for seniors with multiple medical conditions in an integrated health care system. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):123–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaiyachati KH, Gordon K, Long T, et al. Continuity in a VA patient-centered medical home reduces emergency department visits. PloS One. 2014;9(5):e96356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Underhill ML, Kiviniemi MT. The association of perceived provider-patient communication and relationship quality with colorectal cancer screening. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39(5):555–63. doi: 10.1177/1090198111421800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Legare F, Labrecque M, Cauchon M, Castel J, Turcotte S, Grimshaw J. Training family physicians in shared decision-making to reduce the overuse of antibiotics in acute respiratory infections: a cluster randomized trial. CMAJ. 2012;184(13):E726–34. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perry Undum Research/Communication. [Accessed 8 July 2016];Unnecessary Tests and Procedures in the Health Care System: The ABIM Foundation. 2014 Available at: Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/042814_Final-Choosing-Wisely-Survey-Report.pdf.

- 27.Corallo AN, Croxford R, Goodman DC, Bryan EL, Srivastava D, Stukel TA. A systematic review of medical practice variation in OECD countries. Health Policy. 2014;114(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cutler D, Skinner JS, Stern AD, Wennberg DE. National Bureau of Economic Research. Vol. 2013. NBER Working Paper Series; Cambridge, MA: 2013. [Accessed 8 July 2016]. Physician Beliefs and Patient Preferences: A New Look at Regional Variation in Health Care Spending. Available at: http://www.nber.org/papers/w19320. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sirovich BE, Lipner RS, Johnston M, Holmboe ES. The association between residency training and internists' ability to practice conservatively. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1640–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huttner B, Goossens H, Verheij T, Harbarth S. Characteristics and outcomes of public campaigns aimed at improving the use of antibiotics in outpatients in high-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):17–31. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perz JF, Craig AS, Coffey CS, et al. Changes in antibiotic prescribing for children after a community-wide campaign. JAMA. 2002;287(23):3103–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.23.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabuncu E, David J, Bernede-Bauduin C, et al. Significant reduction of antibiotic use in the community after a nationwide campaign in France, 2002-2007. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, Scott A, Parmelli E, Beyer FR. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009255. Cd009255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon J, Rose DE, Canelo I, et al. Medical Home Features of VHA Primary Care Clinics and Avoidable Hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1188–94. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2405-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzales R, Anderer T, McCulloch CE, et al. A cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):267–73. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis MM, Balasubramanian BA, Cifuentes M, et al. Clinician Staffing, Scheduling, and Engagement Strategies Among Primary Care Practices Delivering Integrated Care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(Suppl 1):S32–40. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dine CJ, Miller J, Fuld A, Bellini LM, Iwashyna TJ. Educating Physicians-in-Training About Resource Utilization and Their Own Outcomes of Care in the Inpatient Setting. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):175–80. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00021.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elligsen M, Walker SA, Pinto R, et al. Audit and feedback to reduce broad-spectrum antibiotic use among intensive care unit patients: a controlled interrupted time series analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(4):354–61. doi: 10.1086/664757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309(22):2345–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taggart LR, Leung E, Muller MP, Matukas LM, Daneman N. Differential outcome of an antimicrobial stewardship audit and feedback program in two intensive care units: a controlled interrupted time series study. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:480. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1223-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hughes DR, Sunshine JH, Bhargavan M, Forman H. Physician self-referral for imaging and the cost of chronic care for Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2011;49(9):857–64. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31821b35ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryskina KL, Pesko MF, Gossey JT, Caesar EP, Bishop TF. Brand Name Statin Prescribing in a Resident Ambulatory Practice: Implications for Teaching Cost-Conscious Medicine. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):484–8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00412.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bhatia RS, Milford CE, Picard MH, Weiner RB. An educational intervention reduces the rate of inappropriate echocardiograms on an inpatient medical service. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(5):545–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(6):iii–iv. 1–72. doi: 10.3310/hta8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson I, Cowin LS, Johnson M, Young H. Professional identity in medical students: pedagogical challenges to medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):369–73. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.827968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548–55. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dykes PC, Stade D, Chang F, et al. Participatory Design and Development of a Patient-centered Toolkit to Engage Hospitalized Patients and Care Partners in their Plan of Care. AMIA Annual Symp Proc. 2014:486–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coxeter P, Del Mar CB, McGregor L, Beller EM, Hoffmann TC. Interventions to facilitate shared decision making to address antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(11) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010907.pub2. Cd010907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub4. Cd001431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bank AJ, Gage RM. Annual impact of scribes on physician productivity and revenue in a cardiology clinic. ClinicoEcon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:489–95. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S89329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lyles CR, Sarkar U, Schillinger D, et al. Refilling medications through an online patient portal: consistent improvements in adherence across racial/ethnic groups. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015 doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kruse CS, Bolton K. The effect of patient portals on quality outcomes and its implications to meaningful use: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(2):e44. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith CD. Teaching high-value, cost-conscious care to residents: the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine-American College of Physicians Curriculum. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(4):284–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redberg RF. Less is more. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(7):584. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coory MD, Fagan PS, Muller JM, Dunn NA. Participation in cervical cancer screening by women in rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Queensland. Med J Aust. 2002;177(10):544–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ, Jr, Welch HG. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. JAMA. 2004;291(1):71–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kressin NR, Lin MY. Race/ethnicity, and Americans' perceptions and experiences of over- and under-use of care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:443. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1106-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Natale JE, Joseph JG, Rogers AJ, et al. Cranial computed tomography use among children with minor blunt head trauma: association with race/ethnicity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(8):732–7. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haggerty J, Tudiver F, Brown JB, Herbert C, Ciampi A, Guibert R. Patients' anxiety and expectations: how they influence family physicians' decisions to order cancer screening tests. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1658–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoffmann TC, Del Mar C. Patients' expectations of the benefits and harms of treatments, screening, and tests: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):274–86. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sah S, Elias P, Ariely D. Investigation momentum: the relentless pursuit to resolve uncertainty. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):932–3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colla CH, Morden NE, Sequist TD, Schpero WL, Rosenthal MB. Choosing wisely: prevalence and correlates of low-value health care services in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(2):221–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3070-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Onc. 2008;26(23):3860–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McWilliams JM, Dalton JB, Landrum MB, Frakt AB, Pizer SD, Keating NL. Geographic variation in cancer-related imaging: Veterans Affairs health care system versus Medicare. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):794–802. doi: 10.7326/M14-0650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Birkmeyer JD, Reames BN, McCulloch P, Carr AJ, Campbell WB, Wennberg JE. Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. Lancet. 2013;382(9898):1121–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61215-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pearson SD, Goldman L, Orav EJ, et al. Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: do physicians' risk attitudes make the difference? J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):557–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02640365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tubbs EP, Elrod JA, Flum DR. Risk taking and tolerance of uncertainty: implications for surgeons. J Surg Res. 2006;131(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zaat JO, van Eijk JT. General practitioners' uncertainty, risk preference, and use of laboratory tests. Med Care. 1992;30(9):846–54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barnato AE, Tate JA, Rodriguez KL, Zickmund SL, Arnold RM. Norms of decision making in the ICU: a case study of two academic medical centers at the extremes of end-of-life treatment intensity. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(11):1886–96. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2661-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fisher ES, Wennberg JE, Stukel TA, et al. Associations among hospital capacity, utilization, and mortality of US Medicare beneficiaries, controlling for sociodemographic factors. Health Serv Res. 2000;34(6):1351–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yasaitis LC, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Association between physician supply, local practice norms, and outpatient visit rates. Med Care. 2013;51(6):524–31. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182928f67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ryskina KL, Smith CD, Weissman A, et al. U.S. Internal Medicine Residents' Knowledge and Practice of High-Value Care: A National Survey. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1373–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khullar D, Chokshi DA, Kocher R, et al. Behavioral economics and physician compensation--promise and challenges. New Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2281–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1502312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, Blumenthal D. Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians' practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001;39(8):889–905. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fanari Z, Abraham N, Kolm P, et al. Aggressive Measures to Decrease “Door to Balloon” Time and Incidence of Unnecessary Cardiac Catheterization: Potential Risks and Role of Quality Improvement. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1614–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kerr EA, Lucatorto MA, Holleman R, Hogan MM, Klamerus ML, Hofer TP. Monitoring performance for blood pressure management among patients with diabetes mellitus: too much of a good thing? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(12):938–45. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Verhofsteded R, Smets T, Cohen J, et al. Implementing the care programme for the last days of life in an acute geriatric hospital ward: a phase 2 mixed method study. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:27. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0102-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]