Abstract

Organizations use policies to set standards for employee behaviors. Although many organizations have policies that address workplace bullying, previous studies have found that these policies affect neither workplace bullying for targets who are seeking assistance in ending the behaviors nor managers who must address incidents of bullying. This article presents the findings of a study that used critical discourse analysis to examine the language used in policies written by health care organizations and regulatory agencies to regulate workplace bullying. The findings suggest that the discussion of workplace bullying overlaps with discussions of disruptive behaviors and harassment. This lack of conceptual clarity can create difficulty for managers in identifying, naming, and disciplining incidents of workplace bullying. The documents also primarily discussed workplace bullying as a patient safety concern. This language is in conflict with organizations attending to worker well-being with regard to workplace bullying.

Keywords: government regulation, National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), leadership, management, workplace bullying, health care organizations, organizational culture/climate

Workplace bullying, defined as frequent and persistent negative acts directed toward one or more persons in the workplace, is experienced by approximately 27% to 33% of nurses in the United States (Johnson & Rea, 2009; Simons, 2008). Workplace bullying, which can last for months or years, has been associated with a number of health problems (e.g., new onset cardiovascular disease [Kivimäki et al., 2003]; anxiety and depression [Einarsen & Nielsen, 2015; Nielsen & Einarsen, 2012]; headaches, backaches, stomach pain [Einarsen & Nielsen, 2015]; fibromyalgia [Kivimaki et al., 2004]; and symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress disorder [Nielsen & Einarsen, 2012]). It is estimated that 5.7% of sickness absenteeism among health care workers in the United States is related to workplace bullying (Asfaw, Chang, & Ray, 2013). Workplace bullying often manifests as subtle, easily denied behaviors such as attacks on co-workers’ reputations (e.g., spreading rumors, disparaging their attire or work habits), socially excluding or ignoring co-workers, and undermining co-workers’ abilities to do their jobs effectively through omissions such as withholding information (Einarsen, Hoel, Zapf, & Cooper, 2011). Bullying can also involve subtle physical acts such as invading an individual’s personal space, or making faces at them or behind their backs (Einarsen et al., 2011).

Sweden, France, Spain, Australia, and several provinces in Canada have regulations that require organizations to address workplace bullying (Yamada, 2011). In the United States, although laws address sexual and protected class (e.g., race, national origin, disability, military veteran) harassment, courts have interpreted these laws to exclude generalized bullying (Yamada, 2011). Although U.S. organizations are not legally required to do so, some have voluntarily addressed workplace bullying by adopting anti-bullying policies (Duffy, 2009; Namie & Namie, 2009). However, these policies do not necessarily offer targets adequate protection against bullying, nor do they consistently provide human resource personnel with adequate guidance on how to handle bullying incidents (Cowan, 2011, 2012).

In the United States, hospitals that receive Medicaid funding must be accredited by the Joint Commission (JC), a nonprofit organization that evaluates and ensures health care service quality. In 2009, the JC issued a directive stating that hospitals must address disruptive behaviors perpetrated by employees and physicians. This document has been interpreted as a requirement that hospitals must address workplace bullying (Johnston, Phanhtharath, & Jackson, 2009; Sellers, Millenbach, Ward, & Scribani, 2012). According to a recent study, 61% of nurses in New York State reported their hospitals did not have a policy addressing workplace bullying, and 29% reported that their hospitals’ policies were not enforced (Sellers et al., 2012). Studies in the United States have also reported that targets of bullying, including nurses, do not feel they received adequate support from their organizations (Gaffney, DeMarco, Hofmeyer, Vessey, & Budin, 2012; Namie & Lutgen-Sandvik, 2010). When organizations do not intervene, targets of bullying often feel their best option is to resign (Johnson & Rea, 2009; Lutgen-Sandvik, 2006). Those who do stay report feeling “burned out” and detached from the organization (Laschinger, Grau, Finegan, & Wilk, 2010; Laschinger, Leiter, Day, & Gilin, 2009).

To understand why targets of bullying feel their organizations do not adequately support them, this study explored the discourses of workplace bullying (i.e., defined as the language used in speech and writing to discuss workplace bullying) in the official documents of health care organizations. This study was based on organizational discourse and critical discourse theories. Organizational discourse theory posits that organizations create documents in response to external pressures, such as regulatory agencies (Phillips, Lawrence, & Hardy, 2004). To understand what these external pressures might be, this study also explored how workplace bullying was discussed in documents produced by agencies responsible for regulating hospitals (i.e., the JC) and monitoring hospital working conditions (i.e., Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [NIOSH], and the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries [L&I]).

Critical discourse theory posits that analyzing the language used to discuss issues such as workplace bullying can lead to the identification of entrenched patterns of thought, and behavior, which serve as barriers to issue resolution (Fairclough, 2008). This analysis can also predict how language can be modified to bring about resolution of the identified problem (Fairclough, 2008). Therefore, the goal of this research was to gain an understanding of why organizational responses to workplace bullying might be viewed as inadequate by targets and to offer suggestions as to how language modification might create an environment more responsive to the needs of bullied employees.

Method

This cross-sectional study used Fairclough’s (2003, 2008) critical discourse analysis (CDA). The first step in Fairclough’s CDA identifies the network of practices within which a social problem occurs. This step informs selection of the text to be analyzed. Suitable texts can include written documents and interviews as well as media such as the Internet (Fairclough, 2008). The management of workplace bullying in health care organizations is located in a network of practices, which begins with regulatory oversight. To explore this aspect, documents were collected from the following agencies: OSHA, L&I, NIOSH, and the JC. Although NIOSH is not technically a regulatory agency, it was included in this study because it produces documents that inform OSHA’s actions. Documents produced by the JC were included because directives issued by this agency can affect the working conditions of health care providers (Field, 2007). Finally, organizations issue internal documents, such as policies and procedures in response to regulatory directives (Field, 2007).

Data Collection

Using the search term workplace bullying, documents were obtained from the websites of OSHA, NIOSH, L&I, and the JC. On OSHA’s and L&I’s websites, the researchers found a page titled Workplace Violence. Documents that contained the word bullying, or that dealt with workplace violence in health care, were downloaded from this page. The latter were included because workplace bullying is classified by NIOSH as Type 3, or worker-on-worker, workplace violence (McPhaul & Lipscomb, 2004).

This study was part of a larger study, which also involved interviews with hospital nursing unit managers from seven health care organizations (Johnson, Boutain, Tsai, Beaton, & de Castro, 2015). For the portion of the study reported here, policy documents were obtained from the organizations in which these managers worked: human resources departments of three of the study organizations, public-facing websites of two of the organizations, and one of the interview participants. One organization did not have any pertinent documents. The following search words, derived from the content and titles of documents obtained from human resource departments, were used to search the organizations’ websites: bullying, harassment, code of conduct, and disruptive behaviors.

To protect the identity of the participating health care organizations, identification numbers were assigned for labeling. All references to the names of hospitals were deleted from the documents prior to analysis. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Human Subjects Committee of the University of Washington.

Analysis

Data analyses were conducted using Fairclough’s (2003, 2008) CDA. To aid in coding and analysis, documents were uploaded into Atlas.ti 6.2 (2012), a qualitative data management software program. Coding was guided by a document review protocol derived from Fairclough (2003, 2008) and Liu (2010; see Table 1). To ensure the trustworthiness of the study findings, results were shared with and critiqued by a researcher familiar with CDA.

Table 1.

Document Review Protocol

| Steps in document review process | Elements of each step |

|---|---|

| Criteria for document selection | An official policy or informational pamphlet Current at time of study Issued by hospital organization or agency responsible for regulating hospitals Referenced workplace behaviors such as bullying, harassment, verbal abuse, lateral violence, professional conduct |

| Genre of document | Guideline Regulation Policies and procedures Codes of conduct |

| Analysis of intertextuality | Sources of information (direct citations) References to other documents (indirect citations) |

| Lexical analysis | What words are used to describe undesirable workplace behaviors? |

| Analysis of interdiscursivity | What other issues are discussed in conjunction with workplace behaviors? |

Next, the texts of these documents were analyzed. This process was dictated by the study’s aims (Fairclough, 2008), which were to explore how workplace bullying, and the roles and responsibilities of managers and staff with regard to workplace bullying were discussed in the official documents of health care organizations and the agencies that monitor these organizations. To determine the social practice these documents were intended to influence, the documents were classified by genre (Fairclough, 2008). This classification task was accomplished by examining the structure and function of the documents; documents with similar structures and functions were determined to belong to the same genre. The genres identified in this study were guidelines, regulations, policies and procedures, codes of conduct, and a performance evaluation. Guidelines were defined as documents that suggested a course of action, and regulations were documents that prescribed a course of action and included the possibility of sanctions for noncompliance. The genres of policy and procedures, code of conduct, and performance evaluation were defined as documents that contained one of these identifiers in the title.

The second step in the textual analysis involved an examination of intertextuality, that is, how the various documents in the study related to one another or to documents outside of the study. The referral of one text by another is indicative of a common way of representing a given phenomenon (Fairclough, 2008). Intertextuality is evidenced by direct reporting (e.g., a direct quote of another text) or indirect reporting (e.g., summarizing what is said in another text; Fairclough, 2003). Although the standard for academic texts is that the source of direct and indirect reports of other texts should always be made clear, this principle is not the case for all texts. Some texts contain vague attributions such as “it is said that” or “we are required to,” without specifically citing the source, making it challenging to determine intertextuality (Fairclough, 2003). Indeed, most of the hospital documents that were collected did not cite sources. However, some documents contained phrases and definitions that were practically identical to those that were found in agency documents; in these instances, intertextuality was inferred.

The third step in the textual analysis involved lexical analysis of the documents. Lexical analysis is the exploration of how words were used to describe the phenomenon of interest (e.g., workplace interactions), and words are defined or described. When words are not defined or explained, a common understanding of the terms is assumed (Fairclough, 2003).

The final step in the textual analysis was an examination of interdiscursivity, or the separate, but related, discourses mentioned in conjunction with workplace bullying and other negative workplace interactions (Fairclough, 2008). This step allowed researchers to explore the social context in which an issue is discussed, and the obstacles to overcome if the issue is to be resolved (Fairclough, 2008). Examples of discourses that might appear alongside the discourse of workplace bullying include sexual harassment, workplace violence, and workplace health and safety.

Results

Description of Sample

In total, 22 documents (i.e., 14 from health care organizations and 8 from regulatory agencies) were analyzed (see Table 2). Per the genre analysis, 6 were classified as guidelines; these documents were all issued by government agencies. Two documents were classified as regulations; both were written by the JC. These documents outlined standards that “all accreditation programs” (JC, 2008, p. 1) must follow. Of the health care organization documents, 10 were classified as policies and procedures, 3 as codes of conduct, and 1 as a performance evaluation. Because many of the health care organization documents had similar titles, when they are quoted in this article, they are referred to by the assigned number as well as title (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of Sample by Genre

| Genre | Issued by | Title of document (publication type) | Year issued | Terms used to describe behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guideline | Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) | Workplace Violence (web page) | n.d. | Disruptive behavior Harassment Verbal abuse |

| Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Health Care & Social Service Workers (pamphlet) | 2004 | Verbal and nonverbal threats | ||

| National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) | Workplace Violence Prevention Strategies and Research Needs (pamphlet) | 2006 | Disruptive behavior Bullying Harassment |

|

| Violence: Occupational Hazards in Hospitals (pamphlet) | 2002 | Offensive or threatening behavior | ||

| Washington Department of Labor and Industries (L&I) | Topics: Workplace Violence (web page) | n.d. | Disruptive behavior Harassment Intimidation |

|

| SHARP Report: Workplace Bullying and Disruptive Behavior: What Everyone needs to Know (pamphlet) | 2008 Revised: 2011 |

Disruptive behaviora Harassmenta Bullyinga |

||

| Regulation | The Joint Commission (JC) | Issue 40: Behaviors that Undermine a Culture of Safety | 2008 | Disruptive behaviora |

| Issue 43: Leadership Committed to Safety | 2009 | Disruptive behaviora | ||

| Policy and Procedure | Health Care Organization 1 | Employee Behavioral Standards (1.1) | 2008 | Respect Caring Compassion |

| Workplace Violence Prevention (1.2) | 2009 | Verbal assault Threatening behaviors |

||

| Fitness for Duty (1.3) | 2009 | Disruptive behavior Inappropriate behavior |

||

| Health Care Organization 2 | Management of Disruptive Conduct by Staff, Volunteers, Contractors, and Agency (2.1) | 2009 | Disruptive behaviora Bullying |

|

| Health Care Organization 3 | Anti-Harassment (3.1) | 2004 | Bullying Harassmenta Threatening behavior |

|

| Workplace Violence Prevention (3.2) | 2004 | Harassment Verbal Abuse Threatening language |

||

| Health Care Organization 4 | Harassment Free Environment (4.1) | 2011 | Harassmenta Intimidating behaviors |

|

| Health Care Organization 5 | Standards of Conduct (5.1) | 2009 | Disruptive behaviora Bulling Harassment Intimidation |

|

| Health Care Organization 6 | Disruptive Behavior and Response Guideline (6.1) | 2009 | Disruptive behavior Intimidating behavior |

|

| Interprofessional Relationships (6.2) | 2007 | Disruptive behavior Verbal abuse |

||

| Code of Conduct | Health Care Organization 2 | Standards for Business Conduct (2.2) | 2010 | Harassment Abuse of “any kind” |

| Health Care Organization 3 | Code of Conduct (and addendum) (3.3) | 2010 | Disruptive behaviora Bullying |

|

| Health Care Organization 4 | Code of Ethics and Business Conduct (4.2) | n.d. | Respect | |

| Performance Evaluation | Health Care Organization 2 | Performance worksheet (2.3) | n.d. | Bullying Intimidation |

Contained definitions or descriptions of the terms.

Intertextuality

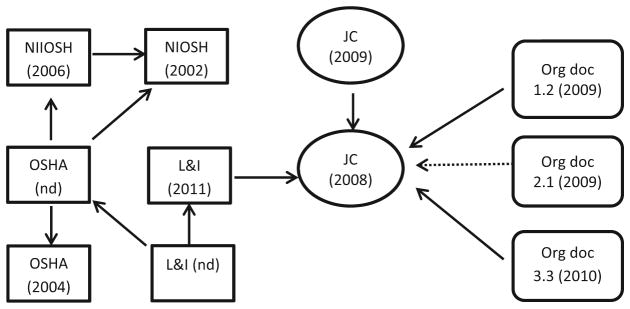

Little evidence indicated intertextuality, or referral to one document by another, among the documents (see Figure 1). The best evidence of intertextuality was in the documents issued by NIOSH, OSHA, and L&I, which contained references to each other. Only three of the health care organization policies listed sources or referred to external regulations or directives. The primary document that health care organizations referred to was Issue 40: Behaviors that Undermine a Culture of Safety (JC, 2008). This document was cited directly by two health care organization policies (1.2 Workplace Violence Prevention & 3.3 Code of Conduct) and one regulatory agency document (L&I, 2011), and indirectly by one health care organization document (2.1 Management of Disruptive Conduct). In the latter, the definition of disruptive behavior was almost a verbatim quote of the definition of disruptive behavior found in the JC (2008) document.

Figure 1.

Representation of intertextuality of documents.

Note. Health care organization documents are symbolized by soft-edged squares, agency guidelines by squares, and agency regulations by ovals. The arrow goes from the citing document to the cited document. Solid lines indicate direct citations; dotted lines indicate indirect citations. Only the organizational documents with evidence of intertextuality are included in this figure.

Lexical Analysis

The following terms were most frequently used to describe bullying-type behaviors: disruptive behavior (12 documents), harassment (9 documents), and bullying (5 documents; see Table 2). Two documents (1.1 Employee Behavioral Standards, 4.2 Code of Business and Ethics Conduct) only discussed positive behaviors such as respect, caring, and compassion.

Although mentioned in 12 documents, disruptive behavior was only defined in five documents. These documents defined it in a similar manner as the JC (2008) document, which defined disruptive behavior as,

actions such as verbal outbursts and physical threats, as well as passive activities such as refusing to perform assigned tasks or quietly exhibiting uncooperative attitudes during routine activities … reluctance or refusal to answer questions, return phone calls or pages; condescending language or voice intonation; and impatience with questions. (p. 1)

Although this document never mentioned workplace bullying, three of the health care organizations’ policies (2.1 Management of Disruptive Conduct, 3.3 Code of Conduct, 5.1 Standards of Conduct) included workplace bullying on their list of disruptive behaviors. In contrast, in the L&I (2011) document, bullying and disruptive behaviors were discussed in two separate sections, implying distinct concepts.

The term harassment was defined in three of the nine documents (see Table 2). In a section titled Bullying is Different From Harassment, the document issued by L&I (2011) defined harassment as,

… one type of illegal discrimination … defined as offensive and unwelcome conduct, serious enough to adversely affect the terms and conditions of a person’s employment, which occurs because of the person’s protected class (p. 3)

and made the point that workplace bullying differs from harassment. In contrast, bullying was included in the description of harassment in another health care organization’s policy:

It [harassment] may also encompass other forms of hostile, intimidating, threatening, humiliating, bullying or violent behaviors that may not necessarily be illegal discrimination, but are nonetheless prohibited by the medical center and this policy. (3.1 Anti-Harassment)

In another health care organization’s document, Standards of Conduct (5.1), harassment was listed as an example of a disruptive behavior. This document did not define the term nor indicate that the concept only applied to members of a legally protected class.

There was only one document that explicitly defined workplace bullying (L&I, 2011). This document stated that workplace bullying is

… repeated, unreasonable actions of individuals (or a group) directed towards an employee (or a group of employees), which are intended to intimidate, degrade, humiliate, or undermine; or which create a risk to the health or safety of the employee(s).

(L&I, 2011, p. 1)

The following examples of bullying behaviors were listed:

… unwarranted or invalid criticism, blame without factual justification, being treated differently than the rest of your group, being sworn at, exclusion or social isolation, being shouted at or humiliated, excessive monitoring or micro-managing, being given work [sic] unrealistic deadlines.

(L&I, 2011, p. 1)

Within NIOSH (2006), workplace bullying was categorized as Type III workplace violence (i.e., worker-on-worker violence). It was not defined, but was listed as one of several “prohibited behaviors among workers, including threatening, harassing, bullying, stalking, etc.” (p. 17). Finally, in the one document that belonged to the genre of performance evaluation (2.3 Performance Evaluation), “bullies or intimidates others” was classified as “Values Based Behaviors, Level 2.” On this form, Level 1 behaviors were unacceptable, Level 2 behaviors were average or acceptable, and Level 3 behaviors were exceptional.

Accompanying Discourses

Two main discourses, patient safety, defined as passages that mentioned patient care, and occupational safety, defined as passages that mentioned the health and well-being of employees, accompanied discussions of workplace bullying and other unacceptable interactions. An example of a patient safety discourse is,

We will avoid any inappropriate and disruptive behaviors that may interfere with patient care delivery and services or any acts that interfere with the orderly conduct of the organization’s or individual’s abilities to perform their jobs effectively. (004.3 Code of Conduct, p. 2)

An example of an occupational safety discourse is,

This policy establishes the … policy and procedure for responses to disruptive behavior that contributes to violence and hostility in the workplace and interferes with patient and staff safety.” (003.1 Disruptive Conduct, p. 1)

Within health care organization documents, patient safety discourses predominated, for example, 12 passages referred to this discourse, although only 4 passages referred to occupational safety. In the documents published by OSHA, NIOSH, and L&I, occupational safety discourses predominated over patient safety discourses. However, only one of these documents (L&I, 2011) specifically mentioned the negative health effects associated with workplace bullying, stating that “Victims of bullying experience significant physical and mental health problems” (p. 2), and that “disruptive behavior [can cause] distress among other staff” (p. 5). In contrast, NIOSH (2006) referred to bullying as a noninjury and nonphysical event (p. 11). Although these documents referred to research studies, none of them mentioned any research on the negative health effects of bullying.

Documents issued by the JC (2008, 2009) were predominately concerned with the impact of disruptive behaviors on patient safety. The 2009 document never mentioned occupational safety. The 2008 document contained the following two references to occupational safety: “the presence of intimidating and disruptive behaviors in an organization … creates an unhealthy or even hostile work environment (JC, 2008, p. 1), and

[Organizations should] conduct all interventions [to deal with disruptive behavior] within the context of an organizational commitment to the health and well-being of all staff, with adequate resources to support individuals whose behavior is caused or influenced by physical or mental health pathologies.

(JC, 2008, p. 2)

Neither of these passages specifies which negative health outcomes targets of disruptive behavior may experience, or suggests ways in which organizations may mitigate these outcomes. The second passage, which highlights the needs of perpetrators, does not mention the needs of targets at all.

Discussion

This study had several important findings. First, multiple words are being used to describe undesirable workplace interactions, yet most of the documents do not define these terms. The absence of definitions indicates that authors assume the terms are commonly understood (Fairclough, 2003). Lack of definitional clarity is problematic as it can result in conflicting interpretations and enforcement of policies (Cowan, 2012; Harrington, Rayner, & Warren, 2012). Poorly worded policies (i.e., not taking time to draft a clearly defined policy) may also indicate that workplace bullying is not a high priority for organizations (Rayner & Lewis, 2011). Several health care organizations included in this study had multiple workplace interaction documents (e.g., code of conduct, anti-harassment policies, and workplace violence policies), which addressed overlapping concepts in slightly different ways. As Cowan (2011) stated, “the seemingly ad hoc nature of using pieces of various policies (code of conduct, harassment, workplace violence) … contributes to the idea that addressing and preventing bullying is not an organizational priority” (p. 317). When organizations convey that addressing workplace bullying is not a priority, these behaviors may be viewed as acceptable ways of interacting within that organization (Hutchinson, Vickers, Wilkes, & Jackson, 2009).

The multiplicity of terms used, both within and between documents, to describe bullying-type behaviors indicates no coherent understanding of these behaviors, and how these terms should be defined and labeled (Lutgen-Sandvik & Tracy, 2012). The absence of a legal definition of workplace bullying in the United States undoubtedly contributes to this lack of clarity. Furthermore, the analysis also revealed that, with the exception of L&I (2011), harassment and bullying were used interchangeably and seemed to have the same meaning within the health care organizations’ documents. This finding can create the impression that employees have legal protection from workplace bullying. However, harassment is defined by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (n.d.) as “unwelcome conduct that is based on race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy), national origin, age (40 or older), disability or genetic information” (para. 2). Considering how harassment and bullying are used in policies and other organizational documents and that harassment is already well understood, legally expanding the definition of harassment might be a possible solution to the problem of inadequate worker protection against bullying (Yamada, 2000). Other countries, including Australia, the United Kingdom, France, and Finland, have expanded the concept of harassment to include bullying behaviors, which could be experienced by all workers (Hansen, 2011; Yamada, 2011). These legal initiatives are relatively new, and although their effect on the incidence and prevalence of workplace bullying is unknown, they do indicate that workplace bullying is not “part of the cost of being employed” (Yamada, 2011, p. 481).

This study also found little discussion of workplace bullying as an occupational hazard within any of the documents, even in those documents issued by government entities (i.e., OSHA, NIOSH, L&I) responsible for the health and safety of workers. Since the 1980s, researchers have found sufficient evidence to suggest that exposure to workplace bullying negatively affects the physical and mental health of targets (Einarsen & Nielsen, 2014; Nielsen & Einarsen, 2012), and the World Health Organization has called for nations to adopt policies that address the morbidity and mortality associated with workplace bullying (Srabstein & Leventhal, 2010). Countries such as Canada, France, Sweden, Norway, and Australia have already recognized that workplace bullying is an occupational hazard and have enacted laws requiring organizations to address this hazard (Yamada, 2011). The United States, as evidenced by this study’s findings, lags behind other countries on identifying and addressing bullying as a workplace hazard.

Finally, the analysis suggests that the discourse of workplace bullying within health care organizations is shaped by the JC, an agency whose primary responsibility is patient safety, and not by agencies responsible for workplace safety. Within the policies issued by health care organizations, more references to documents issued by the JC were found than those issued by occupational health agencies. In addition, patient safety discourses predominated over worker safety discourses within all documents. As a result, managers may only attend to incidents of workplace bullying that affect patient care and ignore those incidents that affect worker well-being. Although no laws require organizations to address workplace bullying, the OSHA of 1970 does require that employers provide a safe and healthy workplace for employees. If OSHA, which is responsible for enforcing this act, were to emphasize psychological violence such as workplace bullying as a workplace hazard, organizations might be motivated to include discussions of the occupational safety and health implications of workplace bullying in their policies (Harthill, 2010). Addition of language acknowledging the negative occupational health consequences associated with workplace bullying would help targets access resources, such as mental health services, that can restore their health (Rayner & Lewis, 2011).

Implications for Practice

Nurses have a history of advocacy for the health and safety of workers (Chamberlin & Lawhorn, 2006; Papa & Venella, 2013). As such, they should advocate for inclusion of language, both at organizational and governmental levels, that strengthens the discussion of workplace bullying as an occupational health and safety issue. Within organizations, nurses, whatever their role (e.g., management, occupational health, education or staff), should review their organizations’ policies to determine whether these policies adequately address workplace bullying and include language that acknowledges that these behaviors negatively affect the health of workers. With the help of practice committees, health and safety committees, and unions, nurses can advocate for changing vague or poorly worded policies. In conjunction with advocacy for policy change, nurses who work in organizations and those who are members of professional organizations can initiate, or participate in, educational campaigns that highlight the negative health effects of workplace bullying. These educational campaigns, which should target the general public, legislators, and employers, can raise awareness outside of the health care sector and call attention to workplace bullying as a societal problem (Namie, 2011).

Limitations

As with any qualitative study, discourse analysis is a subjective endeavor, which can be influenced by the biases of the researchers. Other researchers might interpret the data differently, and dialogue about these differences would become part of the discourse on workplace bullying policy. This study was limited to one geographic area of the United States and was based on a convenience sample of health care organizations willing to participate in the study. Future studies should investigate policies from a large, random sample of health care organizations across the United States to improve generalizability of the findings. Where possible, these studies should not merely ask, “Does your organization have a policy which addresses bullying?” but should also examine the wording of these policies. In addition, other studies have demonstrated that what members of an organization think a policy says about bullying and what the policy actually says can differ (Cowan, 2011).

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrated that examination of discourse can support researchers’, practitioners’, and management’s understanding of the implications of policy language. This in-depth analysis demonstrated how the current discussion of workplace bullying, with its focus on patient safety, does not include a discussion of workplace bullying as an occupational health issue. Nurses who are concerned with workplace health and safety can play a pivotal role in changing these discourses and ensuring that measures are in place to prevent and address workplace bullying.

Applying Research to Practice.

Workplace bullying has negative outcomes on the health of both targets and witnesses of bullying. However, this study indicates that governmental and organizational documents in the United States do not discuss it as an occupational health issue. Nurses should advocate for the inclusion of language in governmental publications and in organizational documents that acknowledge the occupational health implications of workplace bullying. In addition, nurses who work in organizations should review their organizations’ policies to determine whether the issue of workplace bullying is adequately addressed. Where policies are lacking, or unclear, nurses should participate in the drafting of new policies. These steps would benefit those employees who have experienced or who are currently experiencing workplace bullying.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this study came from the Hester McLaws Scholarship, University of Washington, School of Nursing, the National Institutes of Health–National Center for Research Resources (Grant 5KL2RR025015) to Dr. de Castro, and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (Grant 3T42OH008433) to the University of Washington Northwest Center for Occupational Health and Safety.

Biographies

Susan L. Johnson is an assistant professor at the University of Washington Tacoma, Department of Nursing and Healthcare Leadership. Her research interests include workplace bullying, academic incivility, and policy analysis.

Doris M. Boutain is an associate professor at the University of Washington Seattle, School of Nursing, Department of Psychosocial and Community Health. Her research interests include Health Disparity Research, Critical Theory, Community Health Systems, Worry, Stress and Health.

Jenny H.-C. Tsai is an associate professor at the University of Washington Seattle, School of Nursing, Department of Psychosocial and Community Health. Her research interests include ecological determinants of health, immigrant health, community mental health, critical theory, cross-cultural research inquiry, program evaluation.

Arnold B. de Castro is an associate professor at the University of Washington Bothell, School of Nursing. His research principally focuses on occupational health disparities among immigrant and minority worker populations, with an emphasis on how employment and working conditions contribute to chronic stress. He also investigates how work organization factors influence occupational injury and illness risk among health care workers.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Asfaw AG, Chang CC, Ray TK. Workplace mistreatment and sickness absenteeism from work: Results from the 2010 National Health Interview survey. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2013;57:202–213. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin EM, Lawhorn E. Professional issues: Advancing the specialty. In: Salazar M, editor. Core curriculum for occupational and environmental health nursing. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 533–543. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan RL. “Yes, we have an anti-bullying policy, but”: HR professionals’ understandings and experiences with workplace bullying policy. Communication Studies. 2011;62:307–327. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2011.553763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan RL. It’s complicated: Defining workplace bullying from the human resource professional’s perspective. Management Communication Quarterly. 2012;26:377–403. doi: 10.1177/0893318912439474. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy M. Preventing workplace mobbing and bullying with effective organizational consultation, policies, and legislation. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research. 2009;61:242–262. doi: 10.1037/a0016578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen S, Hoel H, Zapf D, Cooper CL. The concept of bullying and harassment at work: The European tradition. In: Einarsen S, Hoel H, Zapf D, Cooper CL, editors. Bullying and harassment in the workplace. 2. New York, NY: CRC Press; 2011. pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen S, Nielsen M. Workplace bullying as an antecedent of mental health problems: A five-year prospective and representative study. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2015;88:131–142. doi: 10.1007/s00420-014-0944-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. London, England: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough N. The discourse of new labour: Critical discourse analysis. In: Wetherell M, Taylor S, Yates SJ, editors. Discourse as data a guide for analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2008. pp. 229–266. [Google Scholar]

- Field RI. Health care regulation in America: Complexity, confrontation, and compromise. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffney DA, DeMarco RF, Hofmeyer A, Vessey JA, Budin WC. Making things right: Nurses experiences with workplace bullying. Nursing Research and Practice. 2012;2012:243210. doi: 10.1155/2012/243210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AM. State of the art report on bullying at the workplace in the Nordic countries. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:701559/FULLTEXT01.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington S, Rayner C, Warren S. Too hot to handle? Trust and human resource practitioners’ implementation of anti-bullying policy. Human Resource Management Journal. 2012;22:392–408. doi: 10.1111/1748-8583.12004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harthill S. The need for a revitalized regulatory scheme to address workplace bullying in the United States: Harnessing the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act. University of Cincinnati Law Review. 2010;78:1250–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson M, Vickers MH, Wilkes L, Jackson D. The worse you behave, the more you seem to be rewarded: Bullying in nursing as organizational corruption. Employee Responsibilities & Rights Journal. 2009;21:213–229. doi: 10.1007/s10672-009-9100-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Boutain D, Tsai JH-C, Beaton R, de Castro AB. An exploration of managers’ discourses of workplace bullying. Nursing Forum. 2015 doi: 10.1111/nuf.12116. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Rea RE. Workplace bullying: Concerns for nurse leaders. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2009;39(2):84–90. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e318195a5fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, Phanhtharath P, Jackson BS. The bullying aspect of workplace violence in nursing. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 2009;32:287–295. doi: 10.1097/NHL.0b013e3181e6bd19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Alert, Issue 40: Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_40_behaviors_that_undermine_a_culture_of_safety/ [PubMed]

- Joint Commission. Sentinel Event, Issue 43: Leadership committed to safety. 2009 Retrieved from: http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_43_leadership_committed_to_safety/ [PubMed]

- Kivimaki M, Leino-Arjas P, Virtanen M, Elovainio M, Keltikangas-Jarvinen L, Puttonen S, … Vahtera J. Work stress and incidence of newly diagnosed fibromyalgia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57:417–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Vartia M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J, Keltikangas-Järvinen L. Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;60:779–783. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.10.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger SK, Grau AL, Finegan J, Wilk P. New graduate nurses’ experiences of bullying and burnout in hospital settings. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010;66:2732–2742. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger SK, Leiter MP, Day A, Gilin D. Workplace empowerment, incivility, and burnout: Impact on staff nurse recruitment and retention outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management. 2009;17:302–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu FC. Dissertation. University of Washington; Seattle: 2010. Exploring preconception policies and health with adult daughters, their maternal mothers, and healthcare providers in rural Zhejiang Province, P.R. China. [Google Scholar]

- Lutgen-Sandvik P. Take this job and …: Quitting and other forms of resistance to workplace bullying. Communication Monographs. 2006;73:406–433. doi: 10.1080/03637750601024156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgen-Sandvik P, Tracy SJ. Answering five key questions about workplace bullying. Management Communication Quarterly. 2012;26:3–47. doi: 10.1177/0893318911414400. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McPhaul K, Lipscomb J. Workplace violence in health care: Recognized but not regulated. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2004;9:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namie G, Lutgen-Sandvik PE. Active and passive accomplices: The communal character of workplace bullying. International Journal of Communication. 2010;4:343–373. doi:1932-8036/20100343. [Google Scholar]

- Namie G, Namie R. U.S. Workplace bullying: Some basic considerations and consultation interventions. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research. 2009;61:202–219. [Google Scholar]

- Namie G, Namie R, Lutgen-Sandvik P. Challenging workplace bullying in the United States: An activist and public communication approach. In: Einarsen S, Hoel H, Zapf D, Cooper CL, editors. Bullying and harassment in the workplace. New York: CRC Press; 2011. pp. 447–468. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Workplace violence prevention strategies and research needs. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2006-144/pdfs/2006-144.pdf.

- Nielsen MB, Einarsen S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work & Stress. 2012;26:309–332. doi: 10.1080/02678373.2012.734709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Papa A, Venella J. Workplace violence in healthcare: Strategies for advocacy. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2013;18(1) doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol18No01Man05. Manuscript 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips N, Lawrence TB, Hardy C. Discourse and institutions. Academy of Management Review. 2004;29:635–652. [Google Scholar]

- Rayner C, Lewis D. Managing workplace bullying: The role of policies. In: Einarsen HHS, Zapf D, Cooper CL, editors. Bullying and harassment in the workplace. 2. New York, NY: CRC Press; 2011. pp. 327–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers K, Millenbach L, Ward K, Scribani M. Horizontal violence among hospital staff RNs and the quality and safety of patient care. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2012;42:483–487. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31826a208f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons S. Workplace bullying experienced by Massachusetts registered nurses and the relationship to intention to leave the organization. Advances in Nursing Science. 2008;31(2):E48–E59. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000319571.37373.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srabstein JC, Leventhal BL. Prevention of bullying-related morbidity and mortality: A call for public health policies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2010;88:403. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.077123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Harassment. n.d Retrieved from http://www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/harassment.cfm.

- Washington Department of Labor and Industries. Workplace bullying and disruptive behavior: What everyone needs to know. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.lni.wa.gov/safety/research/Files/Bullying.pdf.

- Yamada D. The phenomenon of “workplace bullying” and the need for status-blind hostile work environment protection. Georgetown Law Journal. 2000;88:475–536. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada D. Workplace bullying and the law. In: Einarsen S, Hoel H, Zapf D, Cooper CL, editors. Bullying and harassment in the workplace. 2. New York, NY: CRC Press; 2011. pp. 469–483. [Google Scholar]