Abstract

Background

Women living with HIV/AIDS who drink alcohol are at increased risk for adverse health outcomes, but there is little evidence on best methods for reducing alcohol consumption in this population. We conducted a pilot study to determine the acceptability and feasibility of conducting a larger randomized clinical trial of naltrexone vs. placebo to reduce alcohol consumption in women living with HIV/AIDS.

Methods

We designed the trial with input from community and scientific review. Women with HIV who reported current hazardous drinking (>7 drinks/week or ≥4 drinks per occasion) were randomly assigned to daily oral naltrexone (50mg) or placebo for 4 months. We evaluated willingness to enroll, adherence to study medication, treatment side effects, and drinking and HIV-related outcomes.

Results

From 2010 to 2012, 17 women enrolled (mean age 49 years, 94% African American). Study participation was higher among women recruited from an existing HIV cohort study compared to women recruited from an outpatient HIV clinic. Participants took 73% of their study medication; 82% completed the final assessment (7-months). Among all participants, mean alcohol consumption declined substantially from baseline to month 4 (39.2 vs. 12.8 drinks/week, p<0.01) with continued reduction maintained at 7-months. Drinking reductions were similar in both naltrexone and placebo groups.

Conclusions

A pharmacologic alcohol intervention was acceptable and feasible in women with HIV, with reduced alcohol consumption noted in women assigned to both treatment and placebo groups. However, several recruitment challenges were identified that should be addressed to enhance recruitment in future alcohol treatment trials.

Keywords: alcohol consumption, women, HIV infection, clinical trial, naltrexone, HIV viral suppression

INTRODUCTION

Women account for approximately 23% of new HIV infections in the U.S, and rates of HIV are significantly higher in minority women1. With contemporaneous combination antiretroviral treatment (cART), persons with HIV can survive much longer, but may also have an increased risk for other chronic conditions. Many of these conditions such as cardiovascular disease, liver disease, and cancer, are also associated with hazardous alcohol consumption 2–6. In the U.S., women are less likely than men to achieve HIV viral load suppression 7, 8. Additional strategies are needed to better understand and reduce the observed gender gaps in health outcomes for women living with HIV/AIDS.

In persons with HIV infection, hazardous drinking has been associated with lower medication adherence, increased HIV viral load, more rapid disease progression, and increased hospitalization rates 9–12. Hazardous drinking in women is defined by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as exceeding 7 standard drinks per week or more than 3 drinks per occasion 13. Hazardous drinking is relatively common among women living with HIV, with about 6% – 25% reporting current hazardous drinking 14, 15. However, little is known about the optimal strategies to help women with HIV reduce or stop drinking, or whether reductions in drinking will correlate with improved HIV-related health outcomes.

Naltrexone, an opioid-receptor antagonist, is a medication that can be taken once daily with demonstrated safety, tolerability, and efficacy in reducing harmful alcohol consumption across a wide range of study populations and alcohol consumption behaviors 16, 17 and can be used in those not interested in abstinence 18. However, few previous studies of naltrexone included large numbers of women, and none have determined the feasibility and acceptability in women with HIV.

To assess acceptability, we sought to determine whether women with HIV would enroll in a pharmacologic study of naltrexone versus placebo and whether they would attend study visits and adhere to the study medication schedule. To assess feasibility, we sought to determine the proportion of women using hazardous levels of alcohol who would agree to enroll from selected study sites (two sites from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) ongoing cohort study and one HIV outpatient clinical site), and whether women would experience significant side effects if they were offered a prescription medication outside of a traditional care setting and with minimal exclusion criteria. Finally, we obtained pilot data to assess for any preliminary evidence of efficacy, and to finalize plans to conduct a larger randomized clinical trial. In this paper, we discuss several challenges that we faced during the design of the study, and then present findings from the pilot study itself.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pre-Study Planning

Input from potential participants, scientists and the community

We conducted focus groups at each of the study sites to learn more about why women with HIV are drinking alcohol, and how receptive they might be to intervention19. Based on input from grant reviewers, we modified our originally proposed comparison of naltrexone vs. usual care (with a focus on effectiveness) to a more traditional comparison of naltrexone vs. placebo (focus on efficacy). Prior to study initiation, NIAAA scientific program officers hosted a meeting seeking to harmonize key study measures, and we obtained additional input from the WIHS Cohort Executive Committee, the IRBs at the University of Florida, Cook County Health and Hospital Systems, and Georgetown University, a clinical research review committee at the National Institute on Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and a Community Advisory Board in Jacksonville, Florida. The Community Advisory Board agreed that alcohol was a problem in the community, but also cautioned that there could be issues related to stigma, and that most women would not want to be perceived as having a drinking problem. Based on their input, we created a name for the study: WHAT-IF? --Will Having Alcohol Treatment Improve my Functioning? The final study protocol was posted on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01245647).

Study medication

Several options are available for the medication naltrexone, and we considered options such as oral dose adjustment, injectable naltrexone, or alternative medications for persons who could not take naltrexone (e.g. topirimate). The research team opted to use oral naltrexone 50mg once daily for 4 months, with a final follow-up 3 months after stopping study medication. We sought and obtained an FDA exemption to confirm that our proposed use of naltrexone for any women who exceeded recommended drinking amounts was consistent with its existing treatment indication (treatment of alcohol use disorder). Two of our research sites opted to store the medication on site, and the third entered an agreement with a hospital-based research pharmacy. A certified compounding pharmacy produced identical-appearing capsules for naltrexone and placebo (WELLHealthrx, Jacksonville, FL). We chose to have the medications packaged within 8 × 10” cardboard sheets with 30 punch-out pills, to help women remember if they had taken the medication, and to help research staff monitor adherence to study medication.

Staff training

A professional consultant provided formal staff training and data collection software for the timeline follow-back. We had proposed to record the timeline follow-back sessions for quality assurance, but this was precluded by several security and IRB issues related to the storage or transfer of recorded interviews from HIV-positive participants.

Data infrastructure

We created a data collection infrastructure to securely transfer health information from recruitment locations to a central data center. Most of the data collection and monitoring used RedCap software, supported by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute. Because of perceptions that many participants may have literacy issues, we purchased ACASI software (QDS) and placed the majority of survey items into this survey. One of the ACASI questions asked about ongoing abuse. If women indicated current abuse, they received an additional question about whether or not it was OK to let the research staff member know about this at the end of the survey. Our local information technology team wrote a software program to use a “remote desktop” system to securely transfer data files from local computers to the central data team. We sought and obtained a federal Certificate of Confidentiality from NIAAA.

Recruitment and Enrollment

Participants were recruited from three research and clinical settings. In Chicago, IL, and Washington DC, women were recruited from participants in the ongoing Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS), a longitudinal cohort of the national history of women living with HIV/AIDS 20. At these two WIHS research sites, research staff identified potentially eligible women based on their responses to alcohol questions in the WIHS study questionnaires, and then asked these women if they were interested the clinical trial during the time of a semi-annual cohort visit. In Jacksonville, FL, women were recruited from a hospital-based outpatient clinic affiliated with the University of Florida Center for HIV/AIDS Research, Education and Service (UF CARES). Clinic staff were asked to have all patients complete a 3-item alcohol screening questionnaire (AUDIT-C), and to contact the research staff to discuss the study with any woman who exceeded recommended drinking limits and who was willing to hear more about the study. Research staff could then come to the clinic to meet the patient within 10–15 minutes of the phone call.

Women were eligible if they were aged 18 or older, had documented evidence of HIV infection, and met past-month criteria for hazardous drinking (>7 drinks/week or >3 drinks per occasion) 13. Exclusion criteria included contraindications to using naltrexone (current opiate dependence, current prescription opioid medications, positive urine drug screen for opioids, allergic to naltrexone); liver enzymes ≥ 3 times laboratory’s normal range; serum creatinine >2.0; currently pregnant; currently taking a medication for alcohol treatment, tuberculosis, or active viral hepatitis; unable to understand English or the study procedures; current prognosis of less than 1 year to live (e.g. metastatic cancer); abnormal blood pressure at enrollment visit; or by recommendation of a study physician based on any other information available at the time of enrollment. We monitored the reasons for exclusion among women who sought to participate. Research staff were also encouraged to monitor the number of potentially eligible women who declined to participate, and to inquire about reasons for non-participation.

Data Collection

At baseline, participants completed study questionnaires and provided blood samples. The ACASI questionnaire assessed demographic characteristics (age, race, education, etc.), substance use, sexual behavior, and HIV medication adherence 21. Risky sexual behavior was defined as having unprotected sexual intercourse with a male of unknown or HIV-discordant status 22. Attitudes and beliefs related to alcohol consumption and potential benefits of study participation were asked using a 5-point Likert scale with responses dichotomized as agree (“strongly agreed” or “agreed”) or “do not agree” (all other responses).

The timeline follow-back (TLFB) was used to obtain daily drinking data for the 90 days prior to, and 210 days since baseline 23. At baseline, participants also completed the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) 24, the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) to detect current or past alcohol use disorder 25, and the Short Inventory of Problems (SIP), a 15-item measure of consequences of drinking (score 0 – 60) 26. Craving for alcohol was measured by a single item (score 1–10, with 10 being strongest craving). Recent drug use was defined as any self-reported use of benzodiazepines, cocaine, amphetamines, marijuana, or hallucinogens in the past 30 days (persons with recent opioid use were excluded due to naltrexone interaction).

If recent laboratory test results were not readily available from a validated source (e.g. WIHS cohort data), blood samples were obtained to assess CD4 count, HIV viral load, and a comprehensive metabolic panel, unless recent (past 2-months) results were available from another validated source (e.g. WIHS cohort data). HIV viral suppression was defined as <200 copies/ml (or undetectable) to allow a consistent definition across all sites during the time period. At enrollment, a dried blood spot was sent to a commercial laboratory (USTDL, Des Plaines, IL) to test for PEth (phosphatidylethanol), a biomarker of heavy alcohol use over the previous 3 weeks 27.

Randomization, Intervention, and Follow-up

The participants, investigators, and research staff were all blinded to the specific medication assignment. Randomization was done separately by study site, using a computer-generated sequence created by the study biostatistician to assign consecutive study ID numbers to naltrexone or placebo. The research compounding pharmacy produced 30-day cardboard blister packs containing medications that had been randomly assigned to specific subject ID numbers. New participants received the next consecutive ID number and corresponding medication, and thus neither research staff nor participant could determine whether they received naltrexone or placebo. Participants took the first dose at the research site and were observed for at least 30 minutes after taking the medication.

Follow-up

Participants were asked to punch out and take one pill daily for 4 months, with 5 additional in-person follow-up visits (week 2 and months 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7) and 2 telephone follow-up assessments (weeks 1 and 3). At each follow-up assessment up to 4-months, research staff used counseling checklists, based on a study manual developed for another naltrexone clinical trial 28 to help promote adherence to the study medication. During in-person visits, research staff collected data about adherence to study medication, using visual inspection of the punch-out pill packs, and determined as the number of doses taken divided by the number prescribed. We also actively inquired about medication side effects 29 or other adverse events. At each in-person visit, research staff obtained updated information on daily alcohol consumption using the TLFB. Follow-up ACASI assessments conducted at months 2, 4, and 7 assessed drinking consequences, HIV medication adherence, sexual behavior, and craving for alcohol. Follow-up laboratory tests were obtained at 2-weeks (metabolic panel), and at 2, 4 and 7-months (HIV viral load, CD4 count, metabolic panel). Participants could receive up to $475 in incentive payments to support the time and inconvenience of completing all of the study assessments over 7-months. Follow-up incentives were provided regardless of adherence to study medication.

Safety monitoring

We created a plan consistent with funding agency guidelines (NIAAA) that included a Data Safety and Monitoring Board consisting of 3 members independent from the research team. During the study, the research team actively monitored for new symptoms or health conditions, and a study physician reviewed all study laboratory results. During bi-weekly calls, the research team collectively determined whether any reported events or side effects were new or worsened in severity compared to baseline, and if they appeared to be related to study medication due to participant perception or timing of the event. Then, each participant was categorized as having had any drug-related adverse event or not. The research team monitored all study laboratory results, and informed participants when study physicians deemed any results to be of potential clinical significance.

Statistical Analysis

This study was designed as a pilot feasibility and acceptability study. We had initially anticipated recruitment of up to 15 women per site (45 total), with a goal of estimating the potential effect size rather than achieving a statistically-significant result. The study was stopped after 17 women enrolled due to limitations on funding and enrolling all eligible women from the WIHS cohort. Baseline characteristics of women were compared across assigned treatment groups (naltrexone vs. placebo) using t-tests and Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. Analyses were based on intention-to-treat. Primary and secondary outcomes were determined a-priori and measured at the 4-month time-point, which coincided with completion of study medication. The primary outcome was the mean number of drinks per week averaged over the prior 4-weeks. Secondary drinking outcomes included the number of abstinent days in the previous month, the number of binge drinking days in the previous month, the proportion of women meeting criteria for hazardous drinking, and the total score on the SIP (range 0 to 60). Clinical and behavioral outcomes included HIV viral load (detectable vs. undetectable), CD4 count (continuous measure), HIV medication adherence (>95%), and risky sexual behavior (yes/no). We conducted statistical comparisons for each outcome at each study time-point for naltrexone vs. placebo, using Fisher’s exact test, Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test, and Wilcoxon signed rank sum test where appropriate. Persons were analyzed according to their randomized group. We also compared baseline values with values at 2-, 4-, and 7-months for the entire sample (Wilcoxon test), and separately within the naltrexone and placebo groups (Wilcoxon signed rank sum test). We considered adjusting the p-value deemed to be statistically significant to account for multiple outcome testing, but did not make any formal adjustments as this was a pilot study designed to gather preliminary data for a larger study.

RESULTS

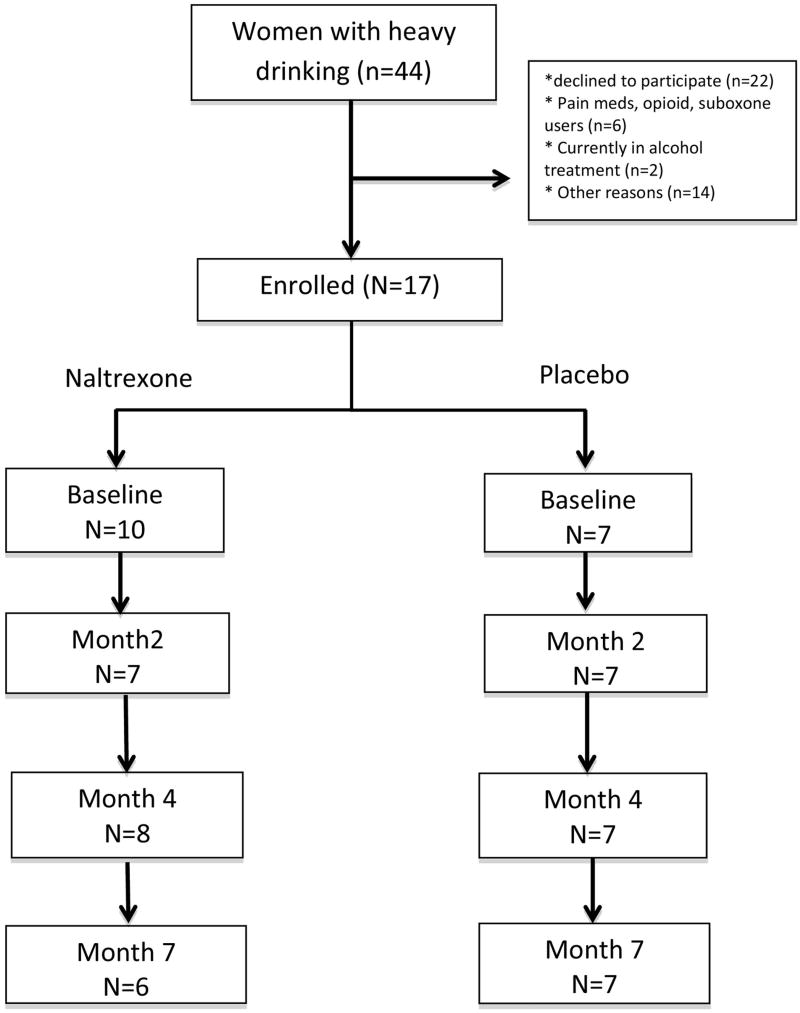

Seventeen women were enrolled in this pilot study (Figure 1). Of 44 women with current alcohol consumption who spoke to clinical or research staff about the study, 22 were either ineligible or declined to participate,10 were randomized to naltrexone and 7 to placebo. The proportion of eligible women who enrolled varied by study site: 13 were eligible and 9 enrolled (70%) from Chicago; 9 were eligible and 6 enrolled (68%) from Washington, DC; and 25 were eligible and 2 enrolled (8%) from Jacksonville, FL. Women recruited from the HIV clinic site were much more likely to either say they were “not interested” or to decline to discuss the study with research staff. Other stated reasons for non-participation included not perceiving drinking to be a problem, and time commitment. Of those enrolled, 15 (88%) completed the 4-month assessment, and 14 completed the 7-month assessment (82%). Overall, women reported taking 73% of the recommended doses of study medication (69% in naltrexone group vs. 78% in placebo group, p=0.55).

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart.

Baseline characteristics of study participants, according to randomization assignment, are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 49 years (SD=7.5); 94% (n=16) were African American, and most (70%) currently used other drugs. At baseline, participants reported an average of 39 standard drinking units (SDU) per week, and an average of 13 binge-drinking days and 10.5 abstinent days in the 30 days prior to enrollment. All participants met criteria for hazardous drinking; the mean AUDIT score was 18.9, 82% met criteria for an alcohol use disorder, and all women had a positive PEth level (alcohol biomarker) at baseline. At baseline, all women agreed that cutting back on drinking would be good for their health, although only 47% agreed that taking medication would help them reduce their drinking, or that they were “extremely” interested in study participation.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 17 women with HIV enrolled in the pilot randomized controlled trial study.

| Naltrexone (n=10) | Placebo (n=7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Age (years; mean, SD) | 48.2 (6.4) | 50.1 (9.3) |

| Race, black (n, %) | 9 (90%) | 7 (100%) |

| Unemployed (n, %) | 9 (90%) | 7 (100%) |

| Education (n, %) > high school | 5 (50%) | 1 (14%) |

| Single/unmarried (n, %) | 9 (90%) | 7 (100%) |

| Any non-opiate drug use (Current) | 6 (60%) | 6 (85%) |

| Recruitment setting | ||

| Chicago (n) | 6 (60%) | 3 (43%) |

| Washington DC (n) | 2 (20%) | 4 (57%) |

| Jacksonville (n) | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| Weekly alcohol consumption (standard drinking units) | ||

| Mean drinks/week (sd) | 33 (4.5) | 48 (15.4) |

| Median drinks/week (IQR) | 31 (24 – 46) | 31 (16 – 75) |

| AUDIT score (mean, sd) | 18.7 (6.6) | 19.1 (9.6) |

| Audit>=16 (n, %) | 6 (60%) | 4 (57%) |

| Alcohol Use Disorder (n, %) | 9 (90%) | 5 (71%) |

| Alcohol treatment in the past year | 1 (10%) | 2 (28.5%) |

| Craving for alcohol (0–10) (mean, SD) | 4.3 (3.1) | 6.1 (3.5) |

| HIV Clinical and Behavioral Variables (Baseline) | ||

| Currently on antiretroviral treatment (ART) | 7 (70%) | 6 (85.7%) |

| >=95% adherence to HIV meds (%) (among those currently on ART) | 4(57.2%) | 3 (50%) |

| Undetectable HIV viral load (n, %) | 5 (50%) | 3 (43%) |

| CD4 count (mean cells/uL) | 652.4 (103.1) | 683.1 (153) |

| Risky sexual behavior (%) | 4 (40%) | 0(0%) |

| Attitudes and beliefs (% agree) | ||

| I sometimes drink too much alcohol (n, %) | 10 (100%) | 6 (85.7%) |

| Cutting down on my drinking would be good for my health (n, %) | 10 (100%) | 7 (100%) |

| Taking drinking medication would help me cut down my drinking (n, %) | 4 (40%) | 5 (71.4%) |

| Extremely interested in participating (n, %) | 4 (40%) | 4 (57.1%) |

AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. None of the differences in baseline characteristics were statistically significantly different at p<0.05

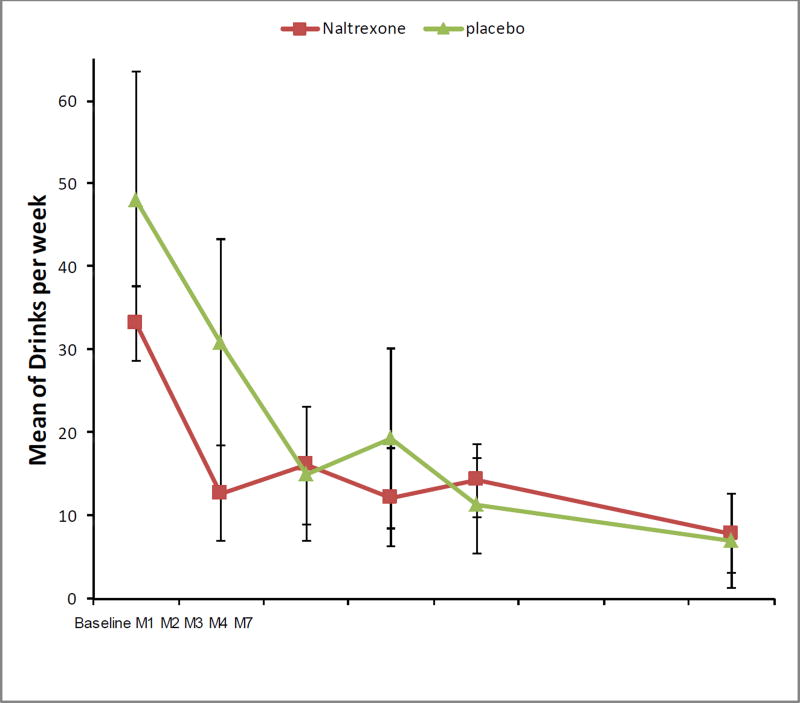

The overall mean weekly alcohol consumption declined significantly among all participants in the study, from 39.2 (SE=6.9) drinks/week at baseline to 12.8 (SE=3.5) drinks/week at month 4 (P<0.05), and 9.4 (SE=3.9) drinks/week at month 7 (P<0.05) (Figure 2). Overall declines were noted in both the naltrexone and placebo groups. For those receiving naltrexone, the mean weekly alcohol consumption declined from 33.2 (SE=4.5) drinks/week at baseline to 14.2 (SE=4.4) drinks/week at month 4 (P=0.078), and 12.2 (SE=5.9) drinks/week at month 7 (P=0.22). For those receiving placebo, the mean weekly alcohol consumption declined from 48.0 (SE=15.4) drinks/week at baseline to 11.2 (SE=5.8) drinks/week at month 4 (P=0.016), and 7.0 (SE=5.6) drinks/week at month 7 (P=0.016).There was no statistically significant difference in drinking reduction by treatment group.

Figure 2.

Mean number of drinks per week in the 17 women randomized to receive naltrexone (n=10) or placebo (n=7).

Both study groups also demonstrated significant increases in the mean number of abstinent days per month. For naltrexone, the mean number of abstinent days per month increased from 9.6 days at baseline, to 20.2 days at 4-months (p=0.023), and 20.3 days at 7-months (p=0.31). The placebo group increased from 11.8 abstinent days per month at baseline to 22.0 days at 4-months, (p=0.03) and 21.8 days at 7-months (p=0.015). There was no statistically-significant difference in mean abstinent days according to treatment group (naltrexone vs. placebo).

Similar changes were noted in both the naltrexone and placebo groups for decreases in the average number of binge drinking days in the previous month, decreases in craving for alcohol, and decreased consequences of drinking (Table 2).

Table 2.

Drinking and clinical outcomes in the 17 women with HIV.

| Naltrexone | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|

| Drinks per week (mean, SE) | ||

| Baseline | 33.1 (4.5) | 48 (15.4) |

| Month 2 | 16.1 (7.1) | 15 (8.1) |

| Month 4 | 14.2 (4.4) | 11.2 (5.8) |

| Month 7 | 12.2 (5.9) | 7 (5.7) |

| Abstinent days in the past 30 days | ||

| Baseline | 9.6 (2.6) | 11.9 (3.6) |

| Month 2 | 19.4 (4.1) | 20.3 (3.6) |

| Month 4 | 20.3 (2.9) | 22 (3.3) |

| Month 7 | 20.3 (4.7) | 21.9 (3.3) |

| Binge drinking days in the past 30 days | ||

| Baseline | 11.8 (2.3) | 14.6 (3.9) |

| Month 2 | 8.1 (3.9) | 6.6 (3.1) |

| Month 4 | 5.9 (1.9) | 5.1 (3.2) |

| Month 7 | 4 (2.1) | 3.4 (3.4) |

| Craving for alcohol (0–10) (mean, SD) | ||

| Baseline | 4.3 (3.1) | 6.1 (3.5) |

| Month 2 | 3.1 (2.3) | 2.4 (2.3) |

| Month 4 | 2.3 (2.1) | 3 (3.5) |

| Month 7 | 1 (0.7) | 2 (3.2) |

| SIP score (Short Inventoryof Problems) (mean, SE) | ||

| Baseline | 11.8 (3.3) | 20.4 (5.1) |

| Month 2 | 3.7 (1.7) | 13.3 (5.4) |

| Month 4 | 2.3 (1.2) | 9.9 (4.2) |

| Month 7 | 2.8 (1.1) | 11.9 (3.9) |

| Risky sexual behavior (%) | ||

| Baseline | 4(40%) | 0(0%) |

| Month2 | 2 (29%) | 1(14%) |

| Month 4 | 2(29%) | 0(0%) |

| Month 7 | 2(40%) | 0(0%) |

| 95% Adherence to ART (%) (among those on ART) | ||

| Baseline | 4(57%) | 3 (50%) |

| Month 2 | 4(67%) | 3 (50%) |

| Month 4 | 3(50%) | 3 (50%) |

| Month 7 | 2(50%) | 4(67%) |

| Undetectable viral load (%) | ||

| Baseline | 5(62%) | 3 (50%) |

| Month 2 | 5 (83%) | 6(86%) |

| Month 4 | 7(88%) | 3(43%) |

| Month 7 | 7(100%) | 6 (86%) |

| CD4 (mean, SE) | ||

| Baseline | 652.4 (103.1) | 683.1 (153.0) |

| Month 2 | 698.2 (191.3) | 635 (183.2) |

| Month 4 | 687.8 (100.2) | 716.0 (171.4) |

| Month 7 | 793.3 (183.7) | 743.0 (189.2) |

Note: Numbers of participants were baseline (n=17), 2-months (n=14), 4-months (n=15), and 7-months (n=13)

The proportion of participants in the entire study sample with undetectable viral load and the mean CD4 both increased somewhat in both the naltrexone and placebo groups (Table 2), but the numbers are too small to make meaningful conclusions. There were no statistically significant differences in outcomes of risky sexual behavior or HIV medication non-adherence according to study assignment.

Although the proportion of participants reporting at least one adverse event attributed to study medication was greater in those receiving naltrexone compared to placebo (70% vs. 28%), these results were not statistically significant (p=0.15 by Fisher exact test). The most common adverse events among those receiving naltrexone were nervousness/anxiety (30%), insomnia (30%), and nausea (10%). One study participant was hospitalized for confusion, weakness, and renal insufficiency on the evening that she started the study medication. A review by two independent physicians concluded that the event was very unlikely to be caused by the study medication; however, the participant was instructed to stop taking the study medication and continue in the study (she was later identified to have been randomized to naltrexone).

DISCUSSION

Our pilot study demonstrated that a pharmacotherapy intervention for hazardous drinking in women living with HIV/AIDS is feasible and acceptable, but that there are likely to be some barriers to participation in a larger clinical trial. Nevertheless, we did find that many women living with HIV/AIDS were willing to participate in this randomized controlled trial, and that participants took at least 70% of their prescribed study medication. Most women, independent of group assignment, substantially reduced their drinking over the initial 4 months while taking study medication, and maintained and/or continued this reduction after stopping study medication. CD4 counts and HIV viral load remained stable and in some instances improved for many women who participated in the study. Our findings are consistent with the overall hypothesis that women living with HIV/AIDS are able to reduce their hazardous drinking, and that reduced drinking may result in improved HIV clinical outcomes.

In terms of study acceptability, we found that recruitment for the study was more challenging from an outpatient clinical setting than from existing clinical research settings, where participants had already demonstrated their willingness to participate in research, and the research staff already knew the participants. We held discussions with both research staff and clinical staff to understand barriers to participation among women in the outpatient clinic, and issues such as stigma, low perception of drinking problems, lack of desire to stop drinking, and/or separation of clinical staff from research staff could have each played a role. Additional research is needed to better understand factors that influence women’s decisions about whether to participate in research studies about stigmatized issues, and to examine methods to enhance recruitment into studies with sensitive topics.

In terms of feasibility, it was not previously clear whether women recruited from outside of traditional substance abuse treatment settings could be assigned to receive naltrexone (or placebo) regardless of current alcohol dependence, mental health problems, or plans for formal detoxification. Our study results suggest that naltrexone can be safely prescribed outside of substance abuse treatment settings in women living with HIV/AIDS who are not taking opiates. However, side effects tended to be common, and a larger sample size is needed to confirm the safety and willingness to continue taking the medication for at least 4 months.

Although our study was not powered to determine efficacy, the fact that women in the placebo group did so well may indicate that women who chose to enroll in the study were already motivated to reduce their drinking, that the multiple alcohol assessments raised awareness about their own consumption, and/or attention from dedicated, trained research staff could help women to improve their drinking behavior 30. The number of follow-up telephone calls, in-person visits and detailed assessments in this research study are different from what a woman would likely receive during a routine clinical encounter, although a recently published study suggests that brief intervention alone can impact alcohol consumption in women living with HIV/AIDS 31. It is also possible that women could intentionally over-estimate their drinking amounts at enrollment (in order to receive research study payments), and then truthfully describe reduced drinking later in the study. It was reassuring that in this study, all women had a positive alcohol biomarker at enrollment indicating recent heavy alcohol use.

Several limitations of the study should be noted. The outcome of drinking alcohol is based primarily on self-report, although a positive PEth biomarker provides confidence regarding baseline drinking status. Although our research staff were trained to remain neutral, social pressure to please the research staff might have influenced self-reported drinking amounts in the latter months of the trial. The small sample size precluded the ability to stratify women according to their severity of drinking, to assess several of the secondary outcomes (such as risky sexual behavior), or to detect statistically significant differences between those assigned to receive naltrexone vs. placebo.

In summary, we found that women living with HIV were able to successfully enroll in a clinical trial for hazardous drinking, were able to reduce drinking substantially, and were willing to return for multiple follow-up visits and assessments. However, recruitment into a larger clinical trial will likely require a broader approach than targeting a single HIV clinic. The study has strong external generalizability to women with HIV, because recruitment took place in several settings and eligibility criteria were broad. Participation in the study resulted in substantial reductions in hazardous drinking in both the naltrexone and placebo groups, with corresponding trends towards improvement in HIV clinical status. The findings from this pilot study therefore indicate that increased social support and detailed alcohol assessments alone could be a strong intervention to reduce drinking in women living with HIV/AIDS.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support. This study received financial support from National Institutes of Health grants R01AA018934 and U24AA02002, U01AI34993, U01AI34994, and from an NIAAA supplement to the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). The WIHS is funded primarily by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), with additional co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), and the National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH). None of the funders had any influence regarding the study design or analyses presented here.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 24, 2016];HIV Among Women. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/. Published 2016.

- 2.Cao Y, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL. Light to moderate intake of alcohol, drinking patterns, and risk of cancer: results from two prospective US cohort studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h4238. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1572–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelso NE, Sheps DS, Cook RL. The association between alcohol use and cardiovascular disease among people living with HIV: a systematic review. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(6):479–488. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2015.1058812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park LS, Hernández-Ramírez RU, Silverberg MJ, Crothers K, Dubrow R. Prevalence of non-HIV cancer risk factors in persons living with HIV/AIDS: a meta-analysis. AIDS Lond Engl. 2016;30(2):273–291. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet Lond Engl. 2014;384(9939):241–248. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60604-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aziz M, Smith KY. Challenges and successes in linking HIV-infected women to care in the United States. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2011;52(Suppl 2):S231–237. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakraborty H, Iyer M, Duffus WA, Samantapudi AV, Albrecht H, Weissman S. Disparities in viral load and CD4 count trends among HIV-infected adults in South Carolina. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(1):26–32. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deiss RG, Mesner O, Agan BK, et al. Characterizing the Association Between Alcohol and HIV Virologic Failure in a Military Cohort on Antiretroviral Therapy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(3):529–535. doi: 10.1111/acer.12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):226–233. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kader R, Govender R, Seedat S, Koch JR, Parry C. Understanding the Impact of Hazardous and Harmful Use of Alcohol and/or Other Drugs on ARV Adherence and Disease Progression. PloS One. 2015;10(5):e0125088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rentsch C, Tate JP, Akgün KM, et al. Alcohol-Related Diagnoses and All-Cause Hospitalization Among HIV-Infected and Uninfected Patients: A Longitudinal Analysis of United States Veterans from 1997 to 2011. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(3):555–564. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1025-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Accessed January 10, 2017];Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide | National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/guide. Published 2008.

- 14.Cook RL, Zhu F, Belnap BH, et al. Alcohol consumption trajectory patterns in adult women with HIV infection. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1705–1712. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0270-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theall KP, Clark RA, Powell A, Smith H, Kissinger P. Alcohol consumption, ART usage and high-risk sex among women infected with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):205–215. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9159-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889–1900. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful? Addiction. 2013;108(2):275–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tidey JW, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Moderators of naltrexone’s effects on drinking, urge, and alcohol effects in non-treatment-seeking heavy drinkers in the natural environment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(1):58–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook RL, Cook CL, Karki M, et al. Perceived benefits and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in women living with HIV: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:263. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2928-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bacon MC, von Wyl V, Alden C, et al. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study: an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12(9):1013–1019. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badiee J, Riggs PK, Rooney AS, et al. Approaches to identifying appropriate medication adherence assessments for HIV infected individuals with comorbid bipolar disorder. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(7):388–394. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook RL, McGinnis KA, Samet JH, et al. Erectile dysfunction drug receipt, risky sexual behavior and sexually transmitted diseases in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected men. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(2):115–121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1164-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. Timeline Follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20) 22-33-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. [Accessed January 10, 2017];The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC) Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/ProjectMatch/match04.pdf. Published 1985.

- 27.Aradottir S, Asanovska G, Gjerss S, Hansson P, Alling C. PHosphatidylethanol (PEth) concentrations in blood are correlated to reported alcohol intake in alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol Oxf Oxfs. 2006;41(4):431–437. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pettinati HM, Mattison ME. [Accessed July 25, 2016];Medical Management Treatment Manual - MMManual.pdf. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/MedicalManual/MMManual.pdf. Published 2010.

- 29.Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Roache JD. The COMBINE SAFTEE: a structured instrument for collecting adverse events adapted for clinical studies in the alcoholism field. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2005;(15):157–167. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.157. discussion 140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Litten RZ, Castle I-JP, Falk D, et al. The placebo effect in clinical trials for alcohol dependence: an exploratory analysis of 51 naltrexone and acamprosate studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(12):2128–2137. doi: 10.1111/acer.12197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chander G, Hutton HE, Lau B, Xu X, McCaul ME. Brief Intervention Decreases Drinking Frequency in HIV-Infected, Heavy Drinking Women: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2015;70(2):137–145. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]