Abstract

Various bacterial taxa have been identified both in association with animals and in the external environment, but the extent to which related bacteria from the two habitat types are ecologically and evolutionarily distinct is largely unknown. This study investigated the scale and pattern of genetic differentiation between bacteria of the family Acetobacteraceae isolated from the guts of Drosophila fruit flies, plant material and industrial fermentations. Genome-scale analysis of the phylogenetic relationships and predicted functions was conducted on 44 Acetobacteraceae isolates, including newly-sequenced genomes from 18 isolates from wild and laboratory Drosophila. Isolates from the external environment and Drosophila could not be assigned to distinct phylogenetic groups, nor are their genomes enriched for any different sets of genes or category of predicted gene functions. In contrast, analysis of bacteria from laboratory Drosophila showed they were genetically distinct in their universal capacity to degrade uric acid (a major nitrogenous waste product of Drosophila) and absence of flagellar motility, while these traits vary among wild Drosophila isolates. Analysis of the competitive fitness of Acetobacter discordant for these traits revealed a significant fitness deficit for bacteria that cannot degrade uric acid in culture with Drosophila. We propose that, for wild populations, frequent cycling of Acetobacter between Drosophila and the external environment prevents genetic differentiation by maintaining selection for traits adaptive in both the gut and external habitats. However, laboratory isolates bear the signs of adaptation to persistent association with the Drosophila host under tightly-defined environmental conditions.

Keywords: Acetobacter, Drosophila, gut microbiota, symbiosis, uric acid

Introduction

It is becoming increasing apparent that the community of microorganisms in healthy animals (the microbiome) can have wide-ranging impacts on the ecology and evolution of the animal host (McFall-Ngai et al. 2013). The microbiome can facilitate the utilization of otherwise intractable food sources by variously providing supplementary nutrients, degrading complex dietary macromolecules and detoxifying dietary toxins (Brune 2014; Hansen & Moran 2014; Karasov & Douglas 2013; Kohl et al. 2014); confer protection against natural enemies, especially microbial pathogens (Jaenike et al. 2010; Stecher & Hardt 2011); and influence behavioral traits that affect gene flow, e.g. mate choice, group recognition, and choice of oviposition and larval settling sites. (Fischer et al. 2017; Lize et al. 2014; Mansourian et al. 2016; Sharon et al. 2010).

Compared to the wealth of data relating to microbial effects on their animal hosts, the impact of these associations on the ecology and evolution of the microbial partners is very poorly understood, but see Soto et al. 2012, and Garcia & Gerardo (2014). In this context, associations can usefully be classified as either “closed”, where the microbial partners are obligately vertically transmitted and, consequently, isolated from the external environment often over multiple host generations; or “open”, where the microbial communities in the host and external environment are connected, such that external microbes colonize the host and host-associated microbes are shed to the external environment, often throughout the life of the animal host. The ecology of microorganisms in closed associations is defined by the animal host and, when sustained for very extended periods (to millions of years), their evolutionary trajectory is dominated by gene loss and genome erosion (McCutcheon & Moran 2012). Open associations present very different selective pressures for microorganisms, favoring traits that promote colonization of the host habitat, competitiveness in interactions with other microbial taxa, and, in many cases, a capacity to persist and proliferate in the external environment.

Open associations are exemplified by the relationship between animals and their gut microbiome. In most animals, the composition of the gut microbiota is influenced not only by microbial compatibility with the conditions and resources in the animal gut habitat, but also by the patterns of colonization by microbes in the food and shedding of microbes in the feces. However, the extent to which the ecology and evolutionary trajectory of gut microorganisms are distinct from related microorganisms in the external environment is largely unknown.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the scale and pattern of genetic differentiation between related bacteria isolated from animal guts and the external environment, recognizing that genetic differences are strongly indicative of ecological differentiation in bacteria (Dutilh et al. 2014; Hehemann et al. 2016). We focused on bacteria of the family Acetobacteraceae, which favor sugar-rich habitats, e.g. rotting fruits, plant nectar (Lievens et al. 2015), and also colonize the guts of various animals feeding on these products (Crotti et al. 2010). In particular, representatives of Acetobacteraceae are prevalent in the microbiota of wild and laboratory Drosophila melanogaster (Chandler et al. 2011; Corby-Harris et al. 2007; Staubach et al. 2013; Wong et al. 2011), and promote rapid development of D. melanogaster larvae (Newell & Douglas 2014; Shin et al. 2011), a critically important trait in the natural environment where larvae exploit the ephemeral resource of rotting fruit (Nunney 1990).

Our specific strategy was to make genome-scale comparisons of, first, the phylogenetic relationships between bacteria isolated from Drosophila guts and external environments; and, second, the gene content of the bacteria, enabling us to address functional variation among the bacterial taxa. For this analysis, we used published genome sequence data for various Acetobacteraceae isolated from plant material and industrial fermentations (we designated these habitats as “external environment”) and from laboratory cultures of D. melanogaster. Because no genome sequences are available for Acetobacteraceae isolated from wild populations of Drosophila, we supplemented the dataset with newly-sequenced genomes from a further 18 isolates of Acetobacteraceae, 14 of which were derived from wild, fruit-feeding Drosophila species. Our analysis revealed no substantive evidence for differentiation between bacteria in the external environment and associated with Drosophila, but the bacteria from laboratory Drosophila are genetically differentiated with respect to specific functional traits.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and identification of Acetobacteraceae associated with Drosophila

Bacteria were isolated from adult Drosophila melanogaster captured directly from field sites; from adult D. suzukii that emerged from collected fruits; and from laboratory-reared D. melanogaster Canton S and W1118 (Table S1). Individual flies were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol, rinsed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), homogenized with a sterile pestle and spread onto Potato medium (PM; 10g/l yeast extract, 10g/l Bacto Peptone (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), 8 g/l Potato Infusion Powder, 5 g/l glucose, and 15g/l agar) and Modified MRS medium (mMRS; 12.5 g/l vegetable peptone (Becton Dickinson), 7.5 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l glucose, 5 g/l sodium acetate, 2 g/l dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, 2 g/l di-ammonium hydrogen citrate, 0.2 g/l magnesium sulfate 7H2O, and 0.05 g/l manganese sulfate 4H2O. Candidate Acetobacteraceae were identified as small, brown, tan or copper-colored colonies, and were isolated by repeated streaking onto PM plates. DNA was isolated from cells grown in liquid culture using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For taxonomic identification, four 16S rRNA gene amplicons were generated for each isolate using primers (Start forward: 5′-GCTTAACACATGCAAGTCGCACG, First third forward: 5′-CTAGCGTTGCTCGGAATGACTG, Last third reverse: 5′-CACCTTCCTCCGGCTTGTCAC, and End reverse: 5′-GGCTACCTTGTTACGACTTCACC), then Sanger sequenced and concatenated to obtain full coverage of the gene.

Sequencing, assembly and annotation of genomes

Libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, targeting an insert size of 500 bp. The average insert size obtained was much larger (~1,200bp), so libraries were further size-selected with a Blue Pippin device (Sage Science, Beverly, MA) targeting fragments ≤800bp. Following DNA quantification with a Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), the libraries were pooled, and 100 bp paired-end reads were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 Platform. Between 3,150,000 and 45,000,000 reads per genome passed quality filtering (300×–4200× coverage). Genome sequences were assembled de novo using Velvet 1.2.03 (Zerbino & Birney 2008), and annotated using the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) server (Aziz et al. 2008) as described previously (Newell et al. 2014). Final assemblies were deposited as Whole Genome Shotgun projects at GenBank, where they were annotated using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (see Table S1 for accession numbers). Analyses in this study were completed using the RAST version of the annotation. Pairwise Average Percent Nucleotide Identity (APNI) was calculated as in Varghese et al. (2015) with the following parameters: minimum length- 80bp, minimum identity- 70%, minimum alignments- 50, window size 200 bp, step size 100 bp.

Identification of orthologous genes and comparisons of gene content across genomes

Sixty-two bacterial genomes were analyzed including draft and complete genomes of Acetobacteraceae in the NCBI Genome Database (as of June 2016) and the 18 generated in this study (Table 1). Orthology of protein coding genes was predicted as described (Newell et al. 2014). Briefly, orthologous groups (OGs) were called de novo using OrthoMCL with inflation factor of 1.5 (Li et al. 2003). A representative protein for each OG was selected using HMMer (hmmer.janelia.org/), and the annotation of the selected protein was retained as the annotation for the cluster (Table S2). A presence/absence matrix for all orthologous genes in all taxa was constructed and the gene contents of bacteria derived from laboratory Drosophila, wild Drosophila and non-Drosophila environments were compared to identify genes significantly associated with each environment.

Table 1.

Genomic information for bacteria isolated in this study. Strains are named according to their origin: Dm denotes isolation from D. melanogaster while Ds denotes isolation from D. suzukii. L denotes isolation from laboratory reared flies while W denotes isolation from wild flies. Pairwise APNI calculations were performed using whole genome sequences of each isolate and whole genome sequences from Acetobacteraceae in the NCBI Genomes database. The genome-sequenced Acetobacteraceae with the highest APNI value is listed on the right.

| Organism | Strain | Genome annotation information | Taxonomic assignment support | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Est. Size (bp) | % GC | CDS | Highest APNI | Organism | ||

| Acetobacter tropicalis | DmW_042 | 3838696 | 55.3 | 3725 | 98.26±2.19 | Acetobacter tropicalis DmCS_006 |

| Acetobacter | DmW_043 | 2646624 | 50.8 | 2500 | 89.58±3.48 | Commensalibacter intestini A911 |

| Acetobacter orientalis | DmW_045 | 2870141 | 52.4 | 2784 | 97.95±1.79 | Acetobacter orientalis 21F-2 |

| Acetobacter indonesiensis | DmW_046 | 3192175 | 53.9 | 3041 | 96.9±2.26 | Acetobacter indonesiensis 5H-1 |

| Acetobacter cibinongensis | DmW_047 | 3242718 | 54.3 | 3168 | 97.06±2.18 | Acetobacter cibinongensis 4H-1 |

| Acetobacter orientalis | DmW_048 | 2747319 | 53.7 | 2660 | 97.85±1.64 | Acetobacter orientalis 21F-2 |

| Acetobacter tropicalis | DmL_050 | 4049721 | 55.7 | 4036 | 97.69±2.04 | Acetobacter tropicalis NBRC 101654 |

| Acetobacter indonesiensis | DmL_051 | 3326569 | 53.9 | 3041 | 98.16±2.16 | Acetobacter indonesiensis 5H-1 |

| Commensalibacter intestini | DmL_052 | 2436068 | 36.8 | 2211 | 99.03±2.3 | Commensalibacter intestini A911 |

| Acetobacter persici | DmL_053 | 3353733 | 58.0 | 3162 | 96.48±2.39 | Acetobacter persici JCM 25330 |

| Acetobacter | DsW_054 | 2716859 | 58.3 | 2578 | 89.92±4.28 | Acetobacter okinawensis JCM 25146 |

| Gluconobacter | DsW_056 | 3175732 | 59.7 | 2997 | 89.55±2.19 | Gluconobacter oxydans 621H |

| Acetobacter malorum | DsW_057 | 3090075 | 57.8 | 2856 | 92.65±3.45 | Acetobacter malorum DmCS_004 |

| Gluconobacter | DsW_058 | 2834931 | 55.8 | 2762 | 89.92±4.98 | Gluconobacter frateurii NBRC 103465 |

| Acetobacter | DsW_059 | 2707336 | 50.6 | 2610 | 89.65±3.47 | Commensalibacter intestini A911 |

| Acetobacter okinawensis | DsW_060 | 2726408 | 58.1 | 2665 | 95.48±3.28 | Acetobacter okinawensis JCM 25146 |

| Acetobacter orientalis | DsW_061 | 2959558 | 52.4 | 2802 | 97.93±1.18 | Acetobacter orientalis 21F-2 |

| Acetobacter nitrogenifigens | DsW_063 | 3040614 | 60.1 | 3041 | 92.9±3.61 | Acetobacter nitrogenifigens DSM 23921 |

Construction of phylogenetic trees using whole genome sequences

A multilocus phylogeny was constructed using 89 single copy orthologous protein sequences present in 47 representative taxa, excluding ortholog families that included proteins with <100 amino acid residues. Granulibacter bethesdensis NIH1 was selected as out-group because the number of orthologous genes in common with the genomes analyzed was greater for this bacterium than all other evolutionarily-divergent acetic acid bacteria that we tested (Saccharibacter floricola DSM 15669, Asaia platycodi SF2, Acidiphilium cryptum ATCC 33463 and Roseomonas oryzae JC288T). A total of 89 proteins were used for the phylogenetic analysis (Table S3). Alignments were constructed using ClustalW on the MEGA5 GUI program with default parameters (Tamura et al. 2013). These alignments were Gblocked, removing gaps and poorly aligned regions (Talavera & Castresana 2007), and the best evolutionary model was determined for each aligned CDS using ProtTest 3 (Darriba et al. 2011). Alignments were concatenated and a phylogenetic tree was built with the online RAxML Blackbox server, performing 100 bootstraps with a partitioned maximum likelihood model that factors in the evolutionary models assigned to each alignment (Stamatakis et al. 2008). Phylogenetic trees for the 16S rRNA gene, as well as other single gene trees, were constructed by the same procedure as for the multilocus tree, and all trees were visualized and manipulated with the program FigTree (tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree). The last 150 bases were omitted from the 16S rRNA gene tree analysis due to variable sequence quality, representing the variable region 9 and an approximately 50 nucleotide conserved region.

Functional Enrichment Analyses

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analyses were conducted using Blast2GO (BioBam, Valencia, Spain). A single amino acid sequence file containing all representative OG sequences and singletons from all genomes was annotated using BLASTp, GO, and KEGG. GO enrichment between categories (flies vs. external environment; laboratory flies vs. wild flies) was conducted in R and accounted for the presence of each GO term in each bacterial species. For example, if a gene with an assigned GO term was present in 5 of 7 lab fly isolates the GO term was counted 5 times. A chi-squared test was performed to compare counts of each GO-term in each category. Chi-square p-values were false-discovery-rate corrected in R.

Rearing gnotobiotic Drosophila and bacterial competition experiments

Drosophila melanogaster Canton S (Wolbachia-free) was maintained at 25°C, 12h:12h light-dark cycle, on a yeast, sucrose, cornmeal diet (all chemicals used in this study were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO unless otherwise noted): 50 g/l brewer’s yeast (inactive; MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA), 40 g/l glucose, 60 g/l yellow cornmeal (Aunt Jemima, Chicago, IL), 12 g/l agar (Apex Bio, Houston, TX) and preservatives (0.04% phosphoric acid, 0.42% propionic acid; 0.1% methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate). Axenic and gnotobiotic D. melanogaster were generated and reared as described (Koyle et al. 2016). Briefly, embryos were surface-sterilized by 3 washes with 0.6% hypochlorite (Clorox, Oakland, CA) followed by 3 washes with sterile water, then transferred aseptically to sterile food. Food composition was 50 g/l brewer’s yeast, 25 g/l glucose, 12g/l agar. Gnotobiotic flies were generated by the addition of approximately 5 × 106 bacterial cells to each vial of dechorionated eggs. To prepare bacteria, cultures were grown 18 h in PM, pelleted by centrifugation 2 min at 8,000 × g, washed once in PBS, then resuspended in PBS to a cell density of 108 cells/ml.

Relative fitness of bacteria was assessed under two conditions: on fly food in the absence of D. melanogaster, and on fly food in the presence of all life stages of D. melanogaster. For competition on food without the insects, cell suspensions of equivalent densities were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and 3 spots of 10 μl each were made on the surface of sterile fly food in a Petri plate. Plates were incubated at 25° C for 12 days, then the cells were recovered with a sterile scraper, resuspended in PBS and cell density determined by serial dilution in a 96-well microtiter plate and spotting onto PM in replicate aliquots of 5 μl. After 48 h incubation, colonies were counted for the 3 replicate aliquots that yielded between 5–50 colonies/spot. Strain pairs were chosen to be discordant for only one trait of interest (e.g. one contains uricase locus while the other does not, but both are motile) and have distinctive colony morphology (Table S4).

To test competitive fitness in the presence of D. melanogaster, bacteria were harvested after 14 days of culture. Adult flies were discarded, 5 ml sterile PBS was added and mixed thoroughly with the food by vortexing (maximum speed for 5–10 seconds). The suspension was then diluted and bacterial cell density assessed as described above. Relative fitness was calculated based on the method of Wiser & Lenski (2015):

where w is fitness, and A and B are the cell densities of the two competitors at initial (i) and final (f) time points. For 5 of 8 competitions between DsW_063 and DmW_047 with Drosophila, no colonies were recovered for the latter strain. To calculate relative fitness in these cases we set the cell density of DmW_047 to the lower limit of detection (500 CFU/ml).

Uric acid determination

The Amplex Red Uric Acid/Uricase determination kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used to measure uric acid concentrations in used fly food. Food samples (10–30 mg) were homogenized in 100 mM Tris pH 7.5 at concentration of 1 mg/10 μl, and solids removed by centrifugation for 1 min at 15,000 × g. Uric acid standards (1–100 μM), were prepared from a 5 mM stock and 100 mM Tris pH 7.5 reaction buffer as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactions were performed in 100 μl volume at 25° C, and substrate fluorescence was measured at 590 nm with a Synergy H1 hybrid plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT), following excitation at 530 nm.

Results

Sequencing and annotation of bacterial genomes

In this study we tested whether bacteria associated with Drosophila are ecologically distinct from bacteria isolated from other environments. We began with a genomic approach, on the rationale that ecological differences should be evident as differentiation, either in taxonomy or gene content, between Acetobacteraceae isolates from Drosophila and the external environment. Because the publically-available genome sequences for Acetobacteraceae lacked representation of bacteria isolated from wild Drosophila, we initiated the study by sequencing the genomes of 14 Acetobacteraceae isolates from wild D. melanogaster and D. suzukii, together with 4 isolates from laboratory-reared D. melanogaster (see Table S5 for assembly information). The genome sequences were assembled de novo, and final draft assemblies annotated by RAST (Aziz et al. 2008). The predicted genome sizes of the isolates ranged from 2.43–4.05 Mb, with 2211–4036 protein coding genes per genome (Table 1).

Taxonomic assignments and phylogenetic analyses

Preliminary taxonomic assignments were made based on genome-wide nucleotide alignments, and/or alignment of 16S rRNA gene sequences. Unambiguous assignments, based on Average Percent Nucleotide Identity (APNI) of ≥95%, could be made for 11 strains (Table 1). In addition, we made species assignments for strains Acetobacter nitrogenifens DsW_063 and Acetobacter malorum DsW_057 based on the multi-locus and 16S phylogenies (see below). Taxonomic assignments of the remaining 5 strains could only be made at the genus level due to a low degree of similarity with other sequences in the NCBI Genomes database (Table 1).

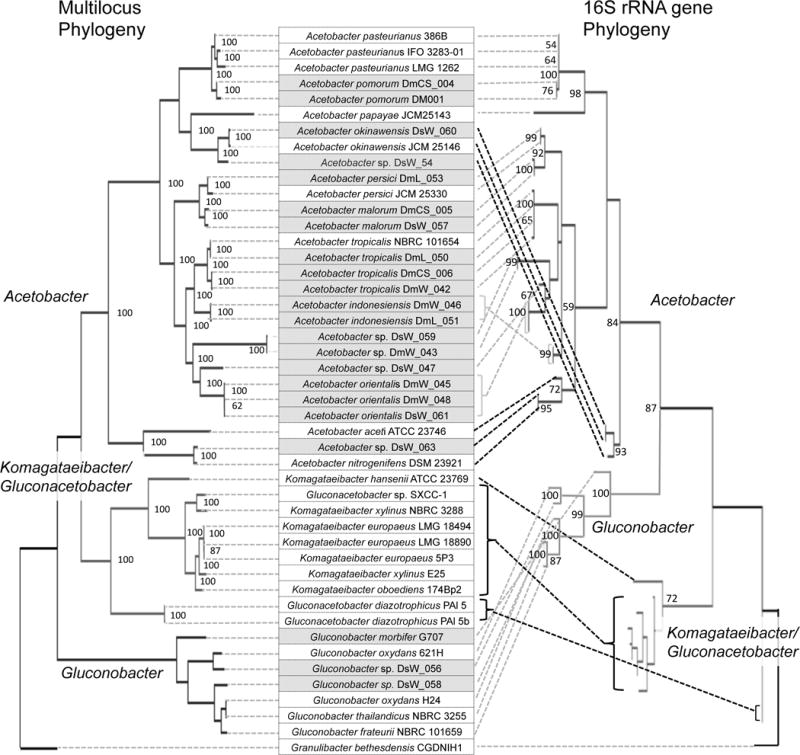

To begin our assessment of whether Drosophila-associated bacteria are distinct from their relatives isolated from other environments, we performed phylogenetic analyses comparing the new isolates to other members of the Acetobacteraeae. Prior work has highlighted inconsistencies between 16S and multi-gene phylogenies of this family (Chouaia et al. 2014; Matsutani et al. 2011), so we included both approaches. Comparing our isolates to 29 other Acetobacteraceae, we also obtained discordant topologies between the 16S tree and a multi-locus tree based on 87 orthologous genes (Fig. 1). Specifically, the sister group of Acetobacter is Gluconobacter in the 16S tree, but Komagataeibacter (formerly Gluconacetobacter) in the multi-locus tree, as previously reported (Chouaia et al. 2014; Matsutani et al. 2011). Despite the discordant topologies, the within-genus relationships are broadly congruent between the two trees, with the exception of the phylogenetic placement of two strains of K. diazotrophicus, and the position of a three-taxon group including A. okinawensis and Acetobacter sp. DsW_054. The latter group is basal in the Acetobacter 16S phylogeny while A. aceti assumes that position in the multi-locus tree. Within these phylogenies, the Drosophila isolates could be assigned to Acetobacter and Gluconobacter, but Komagataeibacter/Gluconacetobacter comprised exclusively isolates from non-Drosophila environments.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of multilocus and 16S rRNA gene phylogenies of Acetobacteraceae. Maximum likelihood phylogenies are shown with bootstrap values at each branch point with support >50%. The taxa compared are listed in the center, in line with their corresponding nodes in the multi-locus tree. Taxa in shaded boxes were isolated from Drosophila. Brackets and dotted lines on the right of the list link the taxa to their corresponding nodes in the 16S rRNA gene phylogeny, illustrating the incongruity of the two trees. Dotted lines in black highlight the most substantial differences in topology.

Further analysis focused on the genus Acetobacter because we obtained too few fly isolates of other genera in the Acetobacteraceae to allow for robust comparisons to congeners from the external environment. Our phylogenies identified Drosophila isolates as broadly distributed across the Acetobacter genus, rather than grouped together. In many cases, taxa that were isolated from the external environment are sister to Drosophila-associated bacteria. Additionally, isolates from D. suzukii and D. melanogaster are intermixed, and a number of isolates from the two Drosophila species appear as sister taxa in the multi-locus tree (e.g. A. orientalis DsW_061 and A. orientalis DsW_048; A. malorum DmCS_006 and A. malorum DsW_057). Therefore our data suggest that the bacteria associated with D. melanogaster and D. suzukii are not consistently phylogenetically distinct from one another, as also suggested by the data in Vacchini et al. (2017) and Rombaut et al. (2017), or from Acetobacteraceae isolates from the external environment.

Comparisons of gene content of Acetobacter from Drosophila and the external environment

To determine whether Acetobacter isolated from Drosophila are functionally different from isolates from the external environment, we compared the full complement of proteins across 42 Acetobacter genomes. Of 24,357 unique genes analyzed, 5474 orthologs groups (OGs) were found in 3 or more genomes. Among these, only 1950 OGs occurred in the majority of genomes (>50%), and no OGs were significantly associated with isolation from Drosophila or the external environment after Bonferroni correction for multiple tests (Fisher’s Exact Test). The gene with the most biased distribution is an aspartate racemase (cluster 3009; P=6.3×10−5), which is the only gene present in the majority of Drosophila isolates but absent from all isolates from the external environment (Table 2, Table S6). No gene has the converse distribution, i.e. is absent from all fly isolates but found in a majority of the other isolates. A parallel analysis using GO term enrichment that included the 68% of OGs found in one or two bacterial strains yielded similar results: none of 1882 GO categories analyzed were significantly enriched in either group of genomes after correcting for multiple tests (Table S7). The category most enriched in the genomes of Drosophila isolates relative to those from the external environment was GO:0036361, encoding for amino acid racemase activity. Together, these results indicate that gene families are shared between Acetobacter strains regardless of their origin and do not support the hypothesis that Drosophila-associated bacteria are functionally differentiated from those isolated from the external environment.

Table 2.

OGs most enriched in bacteria isolated from Drosophila vs. other environments. OG # refers to number assigned during de novo clustering of orthologs. A full list of OGs appears in Table S2; an extended version of this table is Table S6. The group with the greatest number of strains containing the OG is indicated in bold. Fisher’s P values listed have not been corrected for multiple tests. Level of significance after Bonferroni correction was P<9.1×10−6

| OG# | Number of bacterial isolates | Fisher’s P | Annotation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other environments | Fly-associated | |||||

|

| ||||||

| OG Present | OG Absent | OG Present | OG Absent | |||

| 3008 | 0 | 23 | 10 | 9 | 6.28E-05 | aspartate racemase (EC 5.1.1.13) |

| 2051 | 14 | 9 | 1 | 18 | 0.0002 | N-ethylmaleimide reductase |

| 3418 | 1 | 22 | 10 | 9 | 0.0008 | FIG022199: FAD-binding protein |

| 3419 | 1 | 22 | 10 | 9 | 0.0008 | 3-oxoacyl-[ACP] synthase (EC 2.3.1.41) |

| 3420 | 1 | 22 | 10 | 9 | 0.0008 | FIG021862: membrane protein, exporter |

| 3422 | 1 | 22 | 10 | 9 | 0.0008 | Lysophospholipid acyltransferase |

| 1411 | 13 | 10 | 19 | 0 | 0.0008 | multidrug ABC transporter |

| 1575 | 13 | 10 | 19 | 0 | 0.0008 | Na+ or K+ transporter |

| 2864 | 10 | 13 | 0 | 19 | 0.0008 | hypothetical protein |

| 2347 | 2 | 21 | 11 | 8 | 0.0008 | Phosphoglucomutase |

| 2374 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 16 | 0.0017 | maltose acetyltransferase |

| 4043 | 0 | 23 | 7 | 12 | 0.0018 | Branched-chain amino acid transport |

| 4044 | 0 | 23 | 7 | 12 | 0.0018 | hypothetical protein |

| 3833 | 1 | 22 | 9 | 10 | 0.0022 | hypothetical protein |

| 3834 | 1 | 22 | 9 | 10 | 0.0022 | hypothetical protein |

| 2088 | 16 | 7 | 4 | 15 | 0.0023 | methyltransferase |

| 2523 | 2 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 0.0023 | transporter |

| 2927 | 2 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 0.0023 | MFS transporter |

| 3274 | 2 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 0.0023 | 3-hydroxydecanoyl-[ACP] dehydratase |

| 3275 | 2 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 0.0023 | hypothetical protein |

| 3500 | 2 | 21 | 10 | 9 | 0.0023 | hypothetical protein |

Genomic comparison of Acetobacter from wild and laboratory-reared Drosophila

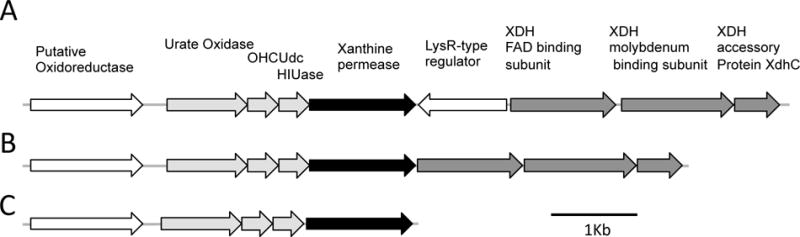

Our second analysis compared genomes of Acetobacter from wild and laboratory Drosophila. None of 4175 OGs present in three or more genomes was significantly associated with laboratory or wild origin when correcting for multiple tests (Table S8). However, multiple genes were universally present in genomes of laboratory isolates but rare in isolates from wild Drosophila (Table 3). Of particular note are a group of genes predicted to function in purine salvage and degradation of uric acid to allantoin. Seven of them form a single locus in all the genomes analyzed, including a putative oxidoreductase, uricase, 5-hydroxyisourate hydrolase, and xanthine permease; the locus is frequently adjacent to genes encoding components of xanthine dehydrogenase (Fig. 2). Microorganisms in laboratory cultures of Drosophila are likely exposed to uric acid, which is a major nitrogen excretory product of insects, including Drosophila.

Table 3.

OGs most enriched in bacteria isolated from laboratory vs. wild Drosophila. OG # refers to number assigned during de novo clustering of orthologs. A full list of OGs comparisons appears in Table S8. Fisher’s P values listed have not been corrected for multiple tests. Level of significance after Bonferroni correction was P<1.26×10−5. Annotations of genes encoded in the uricase locus are shown in bold.

| aOG# | Number of bacterial isolates | bFisher’s P value | cAnnotation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory | Wild | |||||

|

| ||||||

| OG Present | OG Absent | OG Present | OG Absent | |||

| 2066 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 0.003 | lysozyme |

| 2097 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 0.003 | thiosulfate sulfurtransferase |

| 2312 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 0.003 | glycosyl transferase |

| 90 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | transposase |

| 1542 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | purine permease |

| 1543 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | urate oxidase |

| 1554 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | DNA recombination protein RmuC |

| 1623 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | oxidoreductase |

| 1662 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | 5-hydroxyisourate hydrolase |

| 1712 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | ornithine cyclodeaminase |

| 1843 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | SelT |

| 1935 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0.013 | ATP-binding protein |

| 1484 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | amidase |

| 1622 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | xanthine dehydrogenase molybdopterin binding subunit |

| 1663 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | xanthine dehydrogenase accessory protein XdhC |

| 1729 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | xanthine dehydrogenase small subunit |

| 1801 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | permease |

| 1803 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | acetolactate synthase |

| 1936 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | quinone oxidoreductase |

| 1951 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | glycosyl transferase |

| 2211 | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 0.017 | AI-2E family transporter |

| 2160 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 0.017 | transcriptional regulator |

| 1917 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein |

| 2110 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | Chemotaxis response regulator CheB (EC 3.1.1.61) |

| 2338 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | chemotaxis protein CheY |

| 2343 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | export protein FliQ family 3 |

| 2378 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | flagellar motor chemotaxis protein MotA |

| 2379 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | Chemotactic signal-response protein CheL |

| 2382 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | chemotaxis protein CheW |

| 2383 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FliR |

| 2384 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | flagellar basal-body rod protein FlgB |

| 2388 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | Flagellar basal-body rod protein FlgC |

| 2443 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | Flagellar basal-body rod modification protein FlgD |

| 2446 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | flagellar basal body P-ring biosynthesis protein FlgA |

| 2448 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | flagellar M-ring protein FliF |

| 2454 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | flagellar hook-basal body protein FliE |

| 2456 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | chemotaxis protein MotB, partial |

| 2467 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | chemotaxis signal transduction histidine kinase CheA |

| 2505 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | Chemotaxis regulator |

| 2508 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | Flagellar biosynthesis protein FlhB |

| 2553 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 0.044 | flagellar motor switch protein FliN |

Fig. 2.

Uric acid degradation genes found in Acetobacteraceae. The relative size and orientation of putative uric acid degradation genes are shown: light grey, predicted to function in uric acid degradation; dark grey, predicted subunits of xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH); black, predicted xanthine permease. OHCUdc denotes 2-oxo-4-hydroxy-4-carboxy-5-ureidoimidazoline decarboxylase; HIUase denotes 5-hydroxyisourate hydrolase. A) Locus organization found in A. malorum DmCS_005, A. tropicalis DmW_042, A. tropicalis DmCS_006, A. persici DmL_053, A. indonesiensis DmL_051, A. tropicalis DmL_050, and A. indonesiensis DmW_046. B) Locus organization found in A. pomorum DmCS_004, A. pomorum DM001, A. okinawensis DsW_060, Acetobacter sp. DsW_054, and Gluconobacter sp. DsW_056. C) Locus organization found in G. morbifer G707, and Gluconobacter sp. DsW_058.

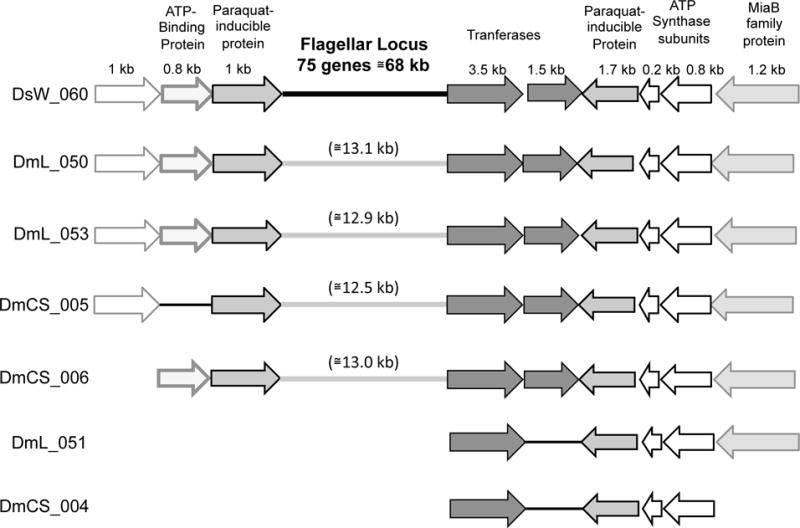

A second difference between the isolates from laboratory and wild Drosophila is that key genes involved in flagellar motility and chemotaxis are present in half of the wild fly isolates but absent from all isolates from laboratory Drosophila. The capacity of these strains for flagellar motility was confirmed by soft agar assays and microscopy (Table S10). To investigate whether remnants of motility genes were present in the genomes of Acetobacter from laboratory flies, we performed systematic blastn searches with genes from the flagellar locus of A. okinawensis DsW_060 as queries. No significant hits were found for genes within this 68 kb locus, whether or not they were predicted to encode flagellar components (Table S11). However, several genes adjacent to the flagellar locus matched conserved genes in the genomes of non-motile Acetobacter (E value < 1×10−20); in four genomes, genes from each side of the flagellar locus were found adjacent to one another, suggesting that deletion of the entire locus could have given rise to the current gene arrangement (Fig. 3). The results are consistent with a model in which flagellar motility is not advantageous for Drosophila microbiota in the laboratory environment, and thus motility genes have been lost from laboratory isolates by deletion.

Fig. 3.

Putative deletion of flagellar genes in non-motile Acetobacter isolates from laboratory Drosophila. Genes from Acetobacter strains listed on the left are shown in relative size and orientation, and color-coded to indicate homology with A. okinawensis DsW_060. A. okinawensis DsW_060 (used as the reference strain) encodes all of its flagellar motility genes at a single locus, depicted as a thick black line. None of the genes within this locus have homologs in the genomes of non-motile strains shown below. However, genes adjacent to the flagellar locus of DsW_060 can be found in the non-motile strains, suggesting that a deletion gave rise to their current arrangement.

We expanded our genomic comparison of Acetobacter isolates from laboratory and wild Drosophila to include all genes annotated with GO terms. This approach confirmed the conclusions from the comparison of OG content. Specifically, Acetobacter from wild Drosophila are significantly enriched in motility genes relative to isolates from laboratory Drosophila. In the seven strains from laboratory Drosophila, only a single gene was categorized into the bacterial-type flagellum (including “–dependent cell motility” and “–organization” subcategories) and chemotaxis categories, relative to 24, 90, 25, and 52 genes in the same respective categories in 12 wild-fly isolates (Table 4). The genomes of laboratory isolates also bore a greater fraction of genes in GO:0006144 “- purine nucleobase metabolic process”, GO:0033971 “-hydroxyisourate hydrolase activity”, and GO:0004854 “-xanthine dehydrogenase activity”, including the uric acid degradation locus and adjacent genes identified in the OG analysis (Table 3, Fig. 2), although these GO terms did not meet the FDR-corrected significance threshold. Together these findings suggest that motility is a key functional difference between bacterial isolates from laboratory- and wild Drosophila, with additional possible differences in uric acid degradation. Next, we sought to verify the findings of our genomic analyses experimentally.

Table 4.

Gene ontology enrichment analysis of isolates form laboratory vs. wild Drosophila

| GO_term | lab | wild | chisq P value | FDR Corrected P value | GO_annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0031514 | 21 | 187 | 2.0162E-19 | 3.43561E-16 | motile cilium |

| GO:0071973 | 1 | 90 | 2.04901E-14 | 1.74576E-11 | bacterial-type flagellum-dependent cell motility |

| GO:0006935 | 1 | 52 | 1.49541E-08 | 8.49395E-06 | Chemotaxis |

| GO:0009425 | 2 | 41 | 2.56931E-06 | 0.001094526 | bacterial-type flagellum basal body |

| GO:0003774 | 2 | 34 | 3.11304E-05 | 0.01060923 | motor activity |

| GO:0044781 | 1 | 25 | 0.000250749 | 0.064434137 | bacterial-type flagellum organization |

| GO:0044780 | 2 | 28 | 0.000264694 | 0.064434137 | bacterial-type flagellum assembly |

| GO:0009288 | 1 | 24 | 0.000361159 | 0.076926796 | bacterial-type flagellum |

| GO:0003796 | 14 | 3 | 0.001327827 | 0.251401977 | lysozyme activity |

| GO:0003677 | 1501 | 1925 | 0.001579295 | 0.269111889 | DNA binding |

| GO:0005198 | 11 | 44 | 0.002340586 | 0.36257806 | structural molecule activity |

| GO:0004871 | 7 | 33 | 0.004067117 | 0.577530562 | signal transducer activity |

| GO:0016705 | 4 | 24 | 0.007106852 | 0.883285446 | oxidoreductase activity |

| GO:0043169 | 19 | 9 | 0.00725704 | 0.883285446 | cation binding |

| GO:0007165 | 6 | 28 | 0.00918262 | 1 | signal transduction |

| GO:0006144 | 14 | 6 | 0.016439852 | 1 | purine nucleobase metabolic process |

| GO:0033971 | 14 | 6 | 0.016439852 | 1 | hydroxyisourate hydrolase activity |

| GO:0000150 | 41 | 35 | 0.030898616 | 1 | recombinase activity |

| GO:0006304 | 15 | 8 | 0.032494476 | 1 | DNA modification |

| GO:0004854 | 17 | 10 | 0.034628702 | 1 | xanthine dehydrogenase activity |

| GO:0016998 | 3 | 9 | 0.036349203 | 1 | cell wall macromolecule catabolic process |

| GO:0009306 | 96 | 46 | 0.043097006 | 1 | protein secretion |

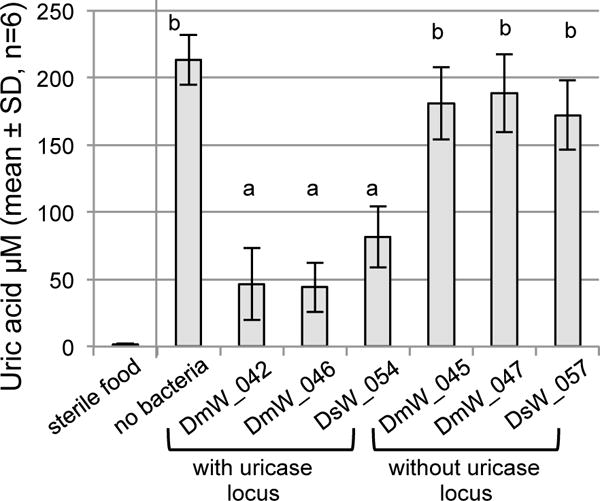

Acetobacter-mediated depletion of uric acid from Drosophila food

We reasoned that spent Drosophila food would contain uric acid and may be an environment in which bacterial degradation of uric acid occurs. To test this hypothesis, we raised axenic flies to adulthood, then removed them from the culture vials and applied bacteria to the Drosophila-conditioned food. After 72 hours of incubation, the concentration of uric acid in the food varied significantly with treatment (ANOVA: F6,35 = 63.07, p<1×10−5), being depleted significantly in food that had been incubated with Acetobacter strains containing the uricase locus (DmW_42, DmW_046 and DsW_054) compared to strains lacking the uricase locus and the bacteria-free control (Fig. 4). Sterile food that had not been exposed to flies had trace amounts of uric acid, near the lower limit of detection for the assay (~1μM; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Depletion of uric acid from Drosophila culture medium by Acetobacter. Used food from axenic Drosophila culture was incubated with the bacterial strains indicated for 72 h, or with no bacteria as control. Uric acid concentration was determined for these samples as well as sterile food that had not been exposed to Drosophila. Different letters above the bars indicate statistically significant differences by Tukey’s HSD test, P<1×10−5 (α=0.002 after Bonferroni’s correction).

Competition between Acetobacter strains in the laboratory environment

The comparative genomic analyses above suggest the ability to degrade uric acid, but not to synthesize flagella might be advantageous for Acetobacter species associated with laboratory cultures of Drosophila. These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the fitness of Acetobacter with the uricase locus and lacking motility genes is significantly elevated in the presence of Drosophila, relative to Acetobacter lacking the uricase locus and with motility, respectively. To test this prediction, we conducted competition experiments between multiple pairs of Acetobacter strains with divergent uricase and motility traits, in the presence and absence of D. melanogaster. The Acetobacter strains with divergent traits were chosen from the isolates from wild Drosophila, so that interpretation of any effects were not confounded by unrelated adaptations of Acetobacter to the laboratory conditions.

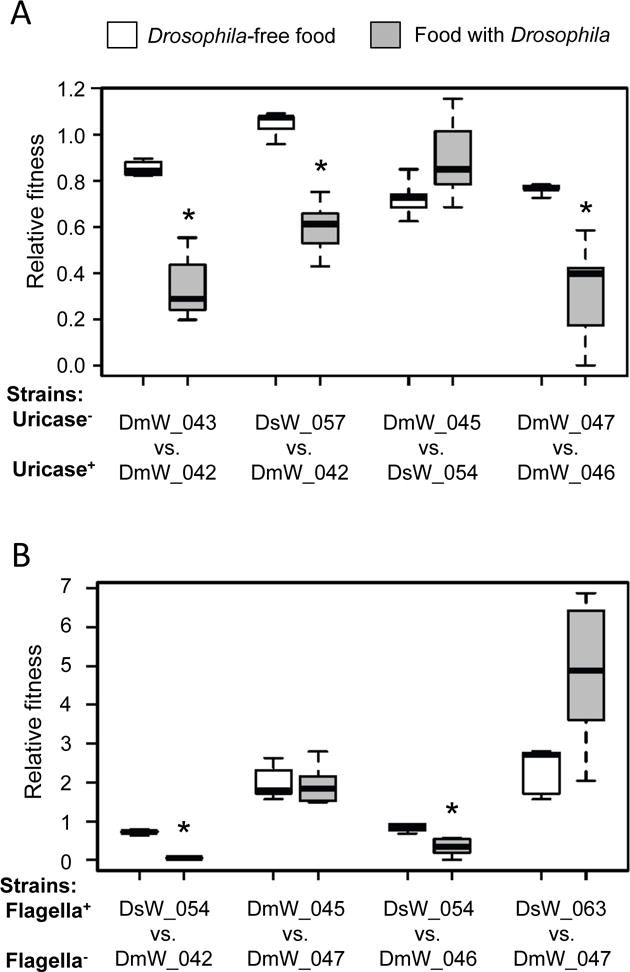

We first investigated the hypothesis that Acetobacter strains lacking the uricase locus would display reduced competitiveness on food containing uric acid produced by Drosophila, compared to the Drosophila-free food condition that lacks uric acid. Bacteria without the uricase locus generally reached lower densities than uricase+ competitors under both conditions tested (Fig. 5A, relative fitness < 1; see Table S12 for cell density values). For three out of four pairs tested, bacteria without uricase showed a significant decrease in competitive fitness in the presence of flies compared to the fresh food condition (Wilcoxon sum rank test, P<0.004; α=0.00625 after Bonferroni’s correction). The one exception was the competition between strains DmW_045 and DsW_054 for which there was not a significant difference in the relative fitness of DmW_045 between the two conditions (Fig. 5A). Altogether, the data suggest that bacteria lacking uricase tend to be less fit when cultured with Drosophila than those that possess the uricase locus.

Fig. 5.

Competitive fitness of Acetobacter isolates from wild Drosophila in laboratory culture. Pairwise competitions were initiated with equivalent cell densities applied to sterile Drosophila food (white bars), or gnotobiotic Drosophila cultures beginning at the embryo stage (grey bars). Asterisks indicate significantly reduced competitive fitness in culture with Drosophila compared to food alone: P<0.004 in Wilcoxon sum rank, α=0.00625 after Bonferroni’s correction. A) The fitness of strains without the uricase locus (Uricase−) relative to strains with the uricase locus (Uricase+) is displayed (n=5 to 8); each box delineates the first and third quartiles, the dark line is the median, and the whiskers show the range. B). The fitness of strains with flagella (Flagella+) relative to strains without flagella (Flagella−) is displayed as in A (n=5 to 8).

We then tested the hypothesis that non-motile bacteria are more competitive than motile bacteria under laboratory Drosophila culture conditions. Using the same experimental protocol as for the analysis of uricase locus, we identified significantly decreased bacterial fitness in the presence of D. melanogaster than on food without the insects for two of the four pairs tested (significantly reduced Drosophila-dependent fitness of DsW_054 relative to DmW_042 and DmW_046) (Fig. 5B; Wilcoxon sum rank test, P<0.004). However, the non-motile strain A. cibinongensis DmW_047 did not display significantly elevated Drosophila-dependent fitness against motile strains (A. orientalis DmW_045 or A. nitrogenifigens DsW_063). This result may be consequent of the competitive inferiority of DmW_047 on the Drosophila food substrate, whether or not the Drosophila was present.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the genetic differentiation between bacteria of the genus Acetobacter that are associated with Drosophila and in the external environment, from both taxonomic and functional perspectives. Published phenotypic and genotypic comparisons have suggested that Drosophila-associated Acetobacter may be functionally distinct from Acetobacter isolates from the external environment (Newell et al. 2014; Petkau et al. 2016), but these studies were limited by small sample sizes and did not include bacteria from wild Drosophila. Here we addressed these shortcomings by comparing genomes from 19 Acetobacter isolates from wild and laboratory Drosophila, as well as 22 Acetobacter species from plant material and industrial fermentations. The inclusion of genomes from wild Drosophila prove to be crucial to the correct interpretation of the data. Specifically, the indications in previous studies of differentiation between Acetobacter isolates from Drosophila and external environments can be attributed to genetic divergence of functionally-important traits in bacteria associated with long-term Drosophila cultures, and not between bacteria in wild Drosophila and the external environment.

Here, we first address the likely selection pressures and functional implications of the genetic differentiation of Acetobacter associated with long-term laboratory cultures of Drosophila; and then consider the evidence for lack of genetic differentiation between Drosophila-associated and free-living isolates of Acetobacter and how these results contribute to our understanding of the ecology of these bacteria under natural conditions.

The Acetobacter isolated from laboratory cultures of Drosophila differ in gene content from isolates from wild Drosophila in relation to two functional traits: their universal possession of genes contributing to uric acid degradation and their absence of key genes in motility. The laboratory strains of Drosophila from which all but one of the Acetobacter were isolated (Canton-S, Oregon-R and white1118) were derived from wild flies collected before 1930 (Lindsley et al. 1972), providing the opportunity for up to 80 years of selection on the bacteria imposed by the laboratory environment.

The capacity of Acetobacter isolated from laboratory cultures of Drosophila to degrade uric acid can be linked to the role of uric acid as a major excretory product of these insects. Soluble urate is released from the Malpigian tubules of the insect into the hindgut, where it is precipitated into uric acid crystals prior to elimination via the feces (Dow & Davies 2003). Consequently, Acetobacter cells in the hindgut and feces are exposed to very high concentrations of uric acid, providing strong selection for the genetic capacity to use uric acid as a nitrogen source. Bacterial consumption of uric acid in laboratory cultures of Drosophila may have far-reaching consequences for the redox balance of the insect. Uric acid can scavenge singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals, and thereby protect cells against oxidative and nitrosative damage, including lipid peroxidation and protein nitrosylation (Ames et al. 1981; Hooper et al. 1998), with the implication that bacterial consumption of uric acid may increase the susceptibility of the insect host to oxidative stress. However, other data indicate that some products of animal-mediated oxidation of uric acid can be toxic and activate pro-inflammatory pathways associated with metabolic dysfunction and obesity (Sautin & Johnson 2008). Acetobacter isolated from laboratory cultures of Drosophila have been demonstrated to protect against the accumulation of excessive lipid in Drosophila (Chaston et al. 2014; Newell & Douglas 2014; Shin et al. 2011), and these considerations raise the possibility that uric acid depletion may contribute to these anti-obesogenic effects.

The second distinctive functional trait of Acetobacter strains isolated from laboratory Drosophila was their loss of motility genes. We hypothesize that motility may generally be advantageous to Acetobacter populations in the external environment and in wild Drosophila. Naturally-occurring microhabitats are generally heterogenous; and adult flies may spend extended periods away from substrates suitable for bacterial growth, favoring bacteria that persist in the gut for many hours or even days. These selective forces are likely relaxed in the laboratory environment, where the food is homogenous and provided ad libitum to the insects, enabling bacteria to cycle continuously between the food substrate and feeding Drosophila. Consistent with this scenario, the evolutionary loss of motility from bacteria reared on homogenous media in the laboratory is common (Fux et al. 2005; Sellek et al. 2002), and the cycling of bacteria between fly and food has been demonstrated empirically for Acetobacter isolated from laboratory Drosophila (Blum et al. 2013). These effects may be compounded by selection for non-motility exerted by certain bacteriophage that utilize the flagellum as receptor (van Houte et al. 2016) and the energetic costs of the proton motive force required for motility (Edwards et al. 2002; Koskiniemi et al. 2012). Interestingly, the host immune system is unlikely to be a factor selecting against motility because, although the bacterial flagellin protein is recognized by the immune system of many animals and plants, Drosophila and other insects apparently lack the receptors that recognize this protein (Buchon et al. 2014).

As a first approach to test whether uric acid utilization and non-motility enhance the fitness of Acetobacter in laboratory cultures of D. melanogaster, we compared the fitness of Acetobacter strains that differed with respect to each trait, in the presence and absence of the insects. We recognize that the Acetobacter strains used in the competition experiments differ at many loci other than motility/uric acid utilization, and that further technical advances in the genetic transformation of Acetobacter, to obtain isogenic strains with specific null mutations, are required to obtain definitive data. Despite this limitation, the results are instructive. Specifically, initial supportive evidence for the selective advantage of the genetic capacity to utilize uric acid in laboratory cultures of Drosophila is provided by the significant increase in relative fitness of these strains relative to competing strains that cannot utilize uric acid in the presence of Drosophila for three of the four pairs of strains tested (Fig. 5A). The competition between motile and non-motile Acetobacter strains yielded more equivocal results (Fig. 5B), and this may reflect fitness differentials that are smaller, e.g. the slight energetic cost of motility in a semi-solid environment, or context-dependent, e.g. significant in presence of bacteriophages that utilize flagella proteins as receptors.

Research on Drosophila in laboratory culture has made important contributions to our fundamental understanding of animal-gut microbiome interactions (Broderick & Lemaitre 2012; Douglas 2011; Erkosar & Leulier 2014). Nevertheless, the microbiota in laboratory Drosophila is taxonomically distinct and of lower diversity than in wild Drosophila (Chandler et al. 2011; Wong et al. 2013), raising questions about the relevance of laboratory studies to natural Drosophila populations. This study contributes to the resolution of this uncertainty. Specifically, by pinpointing specific functional traits, (uric acid utilization and non-motility) that are likely favored in Acetobacter in laboratory cultures, we have identified aspects of host-bacterial interactions that may, indeed, be divergent between laboratory and field Drosophila. Because many of the bacteria in field populations of Drosophila cannot utilize host waste uric acid, the nitrogen relations between Drosophila and its gut microbiota identified in the laboratory (Yamada et al. 2015) may not be relevant for field populations, where the bacteria may compete with the host for other dietary nitrogen sources, such as limiting protein, potentially with negative consequences for host fitness. Furthermore, as argued above, the motility of bacteria in field populations may facilitate persistence in the gut, such that data obtained for laboratory isolates, e.g. (Blum et al. 2013) may underestimate the colonization and residence time of bacteria in natural populations. It is of considerable interest for future work whether laboratory maintenance selects for similar traits, both for other bacteria in Drosophila and for Acetobacter in other animal hosts.

Turning to the broader comparison between Acetobacter isolated from external environments and Drosophila, our analyses yielded no signal for either phylogenetic or functional differentiation (Fig. 1, Table 3, Table S6). Although our analysis cannot provide a definitive demonstration of absence of genetic differentiation between Acetobacter isolates from Drosophila and other environments, our demonstration of significant enrichment for predicted gene functions in the isolates from laboratory vs. wild Drosophila sampled from across the Acetobacter phylogeny argues that the level of differentiation between bacteria associated with Drosophila and those in the external environment would, at most, be small. Further insights may be gained from two complementary strategies. One is to adopt a sampling strategy focused on among-strain variation in a single bacterial species, to obtain a more powerful test for genetic differences between bacterial strains that correlate with their environment. This has been adopted in a study of Lactobacillus plantarum, which is prevalent in both the guts of animals, including Drosophila, and other habitats. Interestingly, the genomic content of L. plantarum is uncoupled from source of isolation (Martino et al. 2016), paralleling our conclusions for Acetobacter. A second strategy would be to address among-strain variation in regulation of gene expression. This is potentially important, given the evidence from other symbioses that evolutionary changes in expression of specific bacterial genes can dictate compatibility with animal hosts (Mandel et al. 2009; Somvanshi et al. 2012).

Interpretation of the apparent lack of genetic differentiation between Acetobacter isolates from Drosophila and external environments is shaped by our current understanding of the ecology of Acetobacter-Drosophila interaction. Under laboratory conditions, populations of Acetobacter are significantly depressed by inclusion of the insects in the vials (Wong et al. 2015). However, this cost of the association for Acetobacter may be offset under natural conditions by the benefit of Drosophila-mediated dispersal (Barata et al. 2012; Gilbert 1980; Staubach et al. 2013). Specifically, in the highly mobile adult insect, bacteria ingested by insects at one feeding site may be defecated at a different feeding site. The selection for fitness in both the Drosophila gut and external environment, together with frequent transfer between different habitats, may select against the evolution of Acetobacter genotypes that are specialized for either habitat. Consistent with this reasoning, various bacterial taxa with no evolutionary history of interactions with Drosophila can colonize these insects, and affect host nutritional indices in ways comparable to bacteria isolated from Drosophila guts (Chaston et al. 2014), suggesting that the Drosophila-gut microbe association is not necessarily founded on specific coevolved adaptations between host and symbiont.

A further consideration is that Drosophila is just one of many insect taxa and other animals that feed from sugar-rich diets bearing Acetobacteraceae (Crotti et al. 2010). This raises the possibility that a diversity of animals provides the ecologically-important service of microbial dispersal in the absence of specific bacterial adaptations for individual animal taxa. Looking ahead, community-level studies of ecology of Acetobacter and other bacteria utilizing ephemeral, sugar-rich habitats under field conditions is required to obtain a clear understanding of the evolutionary and ecological relations between these bacteria and the animals with which they associate.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. List of genomes used in this study, including source of isolates and accession numbers.

Table S2. Annotations for orthologous groups analyzed.

Table S3. List of orthologous proteins used for multilocus phylogeny.

Table S4. Characteristics used to distinguish between strains in competitions.

Table S5. Genome assembly and annotation information.

Table S6. List of OG comparisons of genomes from Drosophila-associated vs. external environment isolates.

Table S7. Gene ontology enrichment analysis of genomes from Drosophila-associated vs. external environment isolates.

Table S8. List of OG comparisons of genomes of isolates from laboratory vs. wild Drosophila.

Table S9. Distribution of all OGs across genomes of Drosophila isolates.

Table S10. Motility assays of bacteria isolated in this study.

Table S11. Blastn analysis of motility genes in isolates from laboratory Drosophila.

Table S12. Cell density data from competition experiments depicted in Fig. 5.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Clark and Artyom Kopp for sharing Drosophila cultures, Edan Foley for sharing genomic data ahead of publication, Greg Loeb and David Sannino for assistance in isolation of bacteria from Drosophila suzukii, and Ghymizu Espinoza and Andrew Sommer for assistance with laboratory experiments. This research was supported by NSF DEB-1241099 and NIH grant R01GM095372 to AED, and Ruth L. Kirschstein NRSA postdoctoral fellowship (1F32GM099374-01) and a grant for Scholarly and Creative Activity from the provost of SUNY Oswego to PDN. The content of this study is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or the NIH.

Footnotes

Data accessibility

Genome sequences are deposited at NBCI and accession numbers are listed in Table S1 in the supporting information. Orthologous group annotations, representat ive sequences and raw data from OG and GO analyses are also available in the supporting information.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Author Contributions

NJW, AED and PDN designed the research. NJW, AW and PDN performed the research. NJW, BC, JMC, AED, and PDN analyzed the data. NJW, AW, JMC, AED and PDN wrote the paper.

References

- Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P. Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:6858–6862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barata A, Santos SC, Malfeito-Ferreira M, Loureiro V. New insights into the ecological interaction between grape berry microorganisms and Drosophila flies during the development of sour rot. Microb Ecol. 2012;64:416–430. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum JE, Fischer CN, Miles J, Handelsman J. Frequent replenishment sustains the beneficial microbiome of Drosophila melanogaster. MBio. 2013;4:e00860–00813. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00860-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick NA, Lemaitre B. Gut-associated microbes of Drosophila melanogaster. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:307–321. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune A. Symbiotic digestion of lignocellulose in termite guts. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:168–180. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchon N, Silverman N, Cherry S. Immunity in Drosophila melanogaster–from microbial recognition to whole-organism physiology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:796–810. doi: 10.1038/nri3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler JA, Lang JM, Bhatnagar S, Eisen JA, Kopp A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaston JM, Newell PD, Douglas AE. Metagenome-wide association of microbial determinants of host phenotype in Drosophila melanogaster. MBio. 2014;5:e01631–01614. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01631-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouaia B, Gaiarsa S, Crotti E, et al. Acetic acid bacteria genomes reveal functional traits for adaptation to life in insect guts. Genome Biol Evol. 2014;6:912–920. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corby-Harris V, Pontaroli AC, Shimkets LJ, et al. Geographical distribution and diversity of bacteria associated with natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:3470–3479. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02120-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotti E, Rizzi A, Chouaia B, et al. Acetic acid bacteria, newly emerging symbionts of insects. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6963–6970. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01336-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. ProtTest 3: fast selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1164–1165. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AE. Lessons from studying insect symbioses. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dow JT, Davies SA. Integrative physiology and functional genomics of epithelial function in a genetic model organism. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:687–729. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutilh BE, Thompson CC, Vicente AC, et al. Comparative genomics of 274 Vibrio cholerae genomes reveals mobile functions structuring three niche dimensions. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:654. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RJ, Sockett RE, Brookfield JF. A simple method for genome-wide screening for advantageous insertions of mobile DNAs in Escherichia coli. Curr Biol. 2002;12:863–867. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00837-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkosar B, Leulier F. Transient adult microbiota, gut homeostasis and longevity: novel insights from the Drosophila model. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4250–4257. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C, Trautman EP, Crawford JM, et al. Metabolite exchange between microbiome members produces compounds that influence Drosophila behavior. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.18855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux CA, Shirtliff M, Stoodley P, Costerton JW. Can laboratory reference strains mirror “real-world” pathogenesis? Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JR, Gerardo NM. The symbiont side of symbiosis: do microbes really benefit? Front Microbiol. 2014;5:510. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DG. Dispersal of yeasts and bacteria by Drosophila in a temperate forest. Oecologia. 1980;46:135–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00346979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AK, Moran NA. The impact of microbial symbionts on host plant utilization by herbivorous insects. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:1473–1496. doi: 10.1111/mec.12421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehemann JH, Arevalo P, Datta MS, et al. Adaptive radiation by waves of gene transfer leads to fine-scale resource partitioning in marine microbes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12860. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper DC, Spitsin S, Kean RB, et al. Uric acid, a natural scavenger of peroxynitrite, in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:675–680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenike J, Unckless R, Cockburn SN, Boelio LM, Perlman SJ. Adaptation via symbiosis: recent spread of a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Science. 2010;329:212–215. doi: 10.1126/science.1188235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasov WH, Douglas AE. Comparative digestive physiology. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:741–783. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl KD, Weiss RB, Cox J, Dale C, Dearing MD. Gut microbes of mammalian herbivores facilitate intake of plant toxins. Ecol Lett. 2014;17:1238–1246. doi: 10.1111/ele.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskiniemi S, Sun S, Berg OG, Andersson DI. Selection-driven gene loss in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyle ML, Veloz M, Judd A, Wong CN, Dobson AJ, Newell PD, Douglas AE, Chaston JM. Rearing the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster under axenic and gnotobiotic conditions. J Vis Exp. 2016;113 doi: 10.3791/54219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Roos DS. OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievens B, Hallsworth JE, Pozo MI, et al. Microbiology of sugar-rich environments: diversity, ecology and system constraints. Environ Microbiol. 2015;17:278–298. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley DL, Grell EH, Bridges CB. Genetic variations of Drosophila melanogaster. Vol. 627 Carnegie institution of Washington; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lize A, McKay R, Lewis Z. Kin recognition in Drosophila: the importance of ecology and gut microbiota. ISME J. 2014;8:469–477. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel MJ, Wollenberg MS, Stabb EV, Visick KL, Ruby EG. A single regulatory gene is sufficient to alter bacterial host range. Nature. 2009;458:215–218. doi: 10.1038/nature07660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansourian S, Corcoran J, Enjin A, et al. Fecal-Derived Phenol Induces Egg-Laying Aversion in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2762–2769. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino ME, Bayjanov JR, Caffrey BE, et al. Nomadic lifestyle of Lactobacillus plantarum revealed by comparative genomics of 54 strains isolated from different habitats. Environ Microbiol. 2016;18:4974–4989. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsutani M, Hirakawa H, Yakushi T, Matsushita K. Genome-wide phylogenetic analysis of Gluconobacter, Acetobacter, and Gluconacetobacter. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2011;315:122–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon JP, Moran NA. Extreme genome reduction in symbiotic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:13–26. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFall-Ngai M, Hadfield MG, Bosch TC, et al. Animals in a bacterial world, a new imperative for the life sciences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3229–3236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218525110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell PD, Chaston JM, Wang Y, et al. In vivo function and comparative genomic analyses of the Drosophila gut microbiota identify candidate symbiosis factors. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:576. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell PD, Douglas AE. Interspecies interactions determine the impact of the gut microbiota on nutrient allocation in Drosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:788–796. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02742-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunney L. Drosophila on Oranges: Colonization, Competition, and Coexistence. Ecology. 1990;71:1904–1915. [Google Scholar]

- Petkau K, Fast D, Duggal A, Foley E. Comparative evaluation of the genomes of three common Drosophila-associated bacteria. Biol Open. 2016;5:1305–1316. doi: 10.1242/bio.017673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rombaut A, Guilhot R, Xuereb A, et al. Invasive Drosophila Suzukii facilitates Drosophila melanogaster infestation and sour rot outbreaks in the vineyards. Royal Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:170117, 1–9. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sautin YY, Johnson RJ. Uric acid: the oxidant-antioxidant paradox. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2008;27:608–619. doi: 10.1080/15257770802138558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellek RE, Escudero R, Gil H, et al. In vitro culture of Borrelia garinii results in loss of flagella and decreased invasiveness. Infect Immun. 2002;70:4851–4858. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4851-4858.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon G, Segal D, Ringo JM, et al. Commensal bacteria play a role in mating preference of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20051–20056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009906107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SC, Kim SH, You H, et al. Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science. 2011;334:670–674. doi: 10.1126/science.1212782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somvanshi VS, Sloup RE, Crawford JM, et al. A single promoter inversion switches Photorhabdus between pathogenic and mutualistic states. Science. 2012;337:88–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1216641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto W, Punke EB, Nishiguchi MK. Evolutionary perspectives in a mutualism of sepiolid squid and bioluminescent bacteria: combined usage of microbial experimental evolution and temporal population genetics. Evolution. 2012;66:1308–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML Web servers. Syst Biol. 2008;57:758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staubach F, Baines JF, Kunzel S, Bik EM, Petrov DA. Host species and environmental effects on bacterial communities associated with Drosophila in the laboratory and in the natural environment. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecher B, Hardt WD. Mechanisms controlling pathogen colonization of the gut. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56:564–577. doi: 10.1080/10635150701472164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Houte S, Buckling A, Westra ER. Evolutionary Ecology of Prokaryotic Immune Mechanisms. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016;80:745–763. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00011-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese NJ, Mukherjee S, Ivanova N, et al. Microbial species delineation using whole genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6761–6771. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacchini V, Gonella E, Crotti E, et al. Bacterial diversity shift determined by different diets in the gut of the spotted wing fly Drosophila suzukii is primarily reflected on acetic acid bacteria. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2017;9:91–103. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser MJ, Lenski RE. A Comparison of Methods to Measure Fitness in Escherichia coli. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AC, Chaston JM, Douglas AE. The inconstant gut microbiota of Drosophila species revealed by 16S rRNA gene analysis. ISME J. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AC, Luo Y, Jing X, et al. The Host as the Driver of the Microbiota in the Gut and External Environment of Drosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:6232–6240. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01442-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CN, Ng P, Douglas AE. Low-diversity bacterial community in the gut of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1889–1900. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada R, Deshpande SA, Bruce KD, Mak EM, Ja WW. Microbes Promote Amino Acid Harvest to Rescue Undernutrition in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. List of genomes used in this study, including source of isolates and accession numbers.

Table S2. Annotations for orthologous groups analyzed.

Table S3. List of orthologous proteins used for multilocus phylogeny.

Table S4. Characteristics used to distinguish between strains in competitions.

Table S5. Genome assembly and annotation information.

Table S6. List of OG comparisons of genomes from Drosophila-associated vs. external environment isolates.

Table S7. Gene ontology enrichment analysis of genomes from Drosophila-associated vs. external environment isolates.

Table S8. List of OG comparisons of genomes of isolates from laboratory vs. wild Drosophila.

Table S9. Distribution of all OGs across genomes of Drosophila isolates.

Table S10. Motility assays of bacteria isolated in this study.

Table S11. Blastn analysis of motility genes in isolates from laboratory Drosophila.

Table S12. Cell density data from competition experiments depicted in Fig. 5.