Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common in pediatric inpatients and associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and length of stay. Early identification can reduce severity.

Methods

To create and validate an electronic health record (EHR)-based AKI screening tool, we generated temporally distinct development and validation cohorts using retrospective data from our tertiary care children’s hospital, including children 28 days through 21 years old with sufficient serum creatinine measurements to determine AKI status. AKI was defined as 1.5-fold or 0.3 mg/dL increase in serum creatinine. Age, medication exposures, platelet count, red blood cell distribution width, serum phosphorus, serum transaminases, hypotension (ICU only), and pH (ICU only) were included in AKI risk prediction models.

Results

For ICU patients, 791/1332 (59%) of the development cohort and 470/866 (54%) of the validation cohort had AKI. In external validation, the ICU prediction model had C-statistic=0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.71–0.77). For non-ICU patients, 722/2337 (31%) and 469/1474 (32%) had AKI, and the prediction model had C-statistic=0.69 (0.66–0.72).

Conclusions

AKI screening can be performed using EHR data. The AKI screening tool can be incorporated into EHR systems to identify high risk patients without serum creatinine data, enabling targeted laboratory testing, early AKI identification, and modification of care.

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) occurs in approximately 25% of children admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) and 5% of those admitted to non-ICU pediatric wards, although application of different diagnostic criteria results in broad incidence estimates.(1–10) Among pediatric ICU patients, AKI is associated with increased length of stay and demonstrates odds ratios >3 for mortality.(1,2,8,9,11,12) Seminal efforts to identify children with AKI through screening of at-risk populations have reduced AKI severity, likely due to early identification and modification of AKI risk factors.(13,14) Recently, the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative Consensus Conference identified AKI as a target for risk prediction and recommended development of AKI alert systems that will “continuously and automatically monitor and assess a patient’s risk for developing AKI.”(15,16)

The primary goal of this study was to develop and validate AKI risk prediction models in pediatric ICU and non-ICU patients that use data from electronic health records (EHR) to identify patients in whom laboratory testing, namely measurement of serum creatinine to assess renal function, is indicated. Prediction models that can be calculated in real time in the EHR and do not rely upon prior serum creatinine values will enable AKI risk prediction across a broad pediatric population, including those not in well-described high risk populations and for whom no serum creatinine data are available.

Methods

Population and EHR Data Extraction

This study was reviewed and approved by the Vanderbilt institutional review board who granted a waiver of the informed consent process. Inclusion criteria for the development cohort were age 28 days through 21 years, measurement of baseline and an additional inpatient serum creatinine as defined below, and admission between 1/1/2011 and 12/31/2012. Exclusion criteria were Neonatal ICU admission (based on location codes) and chronic kidney disease (CKD, based on ICD-9 and CPT codes, Supplemental Table S1 (online)), both of which can be applied prospectively in EHR systems.(17) In addition, those not meeting the AKI definition but with persistent serum creatinine measurements above the normal range for age and sex were excluded, as it is unclear whether they represent AKI without a measured baseline or no-AKI controls. Admissions were assigned to the ICU cohort if the patient received ICU care at any time during the hospitalization; thus, a patient cared for in the ICU who subsequently was transferred to the floor was included in the ICU cohort for both the development and validation cohorts. Validation cohorts used admissions from 1/1/2013 to 12/31/2013 with identical inclusion and exclusion criteria. All study data, including demographic, laboratory, medication administration, and administrative data, were extracted from EHR data sources using Vanderbilt’s research data warehouse and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture).(18,19) Medications were categorized as high risk nephrotoxins if they are highly associated with renal injury (e.g. aminoglycosides, tacrolimus), moderate risk nephrotoxins if they are associated with renal injury in some circumstances, (e.g. loop diuretics, enalapril), or non-nephrotoxins (Supplemental Table S2 (online)). For each individual, the number of unique medications in each category was tallied, and three medication-related continuous variables were analyzed (high risk nephrotoxins, moderate risk nephrotoxins, and total medications). Peri-admission data included all data available from the 24 hours before the inpatient admission order through 48 hours after admission. For model development, covariate data were ascertained from the 72 hours before the serum creatinine measurement that defined AKI status. Further details are available in the Supplemental Materials (online).

Outcome Definition

Although serum creatinine is not a covariate in the risk prediction models, the AKI outcome is defined by change in creatinine (Supplemental Figure S1 (online)). Baseline creatinine was defined as the lowest measurement obtained 90 days before through the first week of admission. Inpatient creatinine was defined as any obtained in the 24 hours prior to the admission order through discharge. AKI was defined solely using the creatinine criteria, as reliable urine output data were not available for all pediatric inpatients,(15) and accurate height measurements were not consistently available for estimated glomerular filtration rate. Patients were classified as having AKI using the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) serum creatinine criteria if any inpatient creatinine measurement was ≥0.3 mg/dL above the baseline or ≥1.5-fold more than the baseline, without the restriction that the increase in serum creatinine occur within 48 hours or 7 days, respectively, as defined in the guidelines.(7) Those not meeting these criteria were classified as no-AKI controls.

Covariate Selection and Statistical Analysis

Predictor variables were selected from candidate variables to balance the following goals: 1) Real-time availability; 2) Correlation to AKI; 3) Limited collinearity; 4) Either low missingness or ability to transform to a categorical variable. For ICU patients, predictor variables were age at admission, high risk nephrotoxins, moderate risk nephrotoxins, total medications, minimum platelet count, median red cell distribution width (RDW), phosphorus, serum transaminases, minimum pH, and hypotension. The same predictors were used for non-ICU patients, excluding pH and hypotension. Further details on the candidate and final variables are available in the Supplemental Materials (online).

The ICU and non-ICU cohorts were analyzed in parallel, generating two distinct AKI prediction models. Descriptive statistics were presented as median [interquartile range (IQR)] or frequency (%). Continuous variables were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test and categorical variables using Pearson chi-square test. We analyzed the association between AKI and the a priori selected covariates using multivariable logistic regression for ICU and non-ICU admissions. We internally validated and calibrated the models using bootstrapping.(20) External validation of each model was performed by evaluating model performance in the temporally distinct validation cohorts. All analyses were performed with R, version 2.14.1 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria). The level of statistical significance was set at p <0.05. Further details are available in the Supplemental Methods (online).

Results

Model Development and Internal Validation for ICU Patients

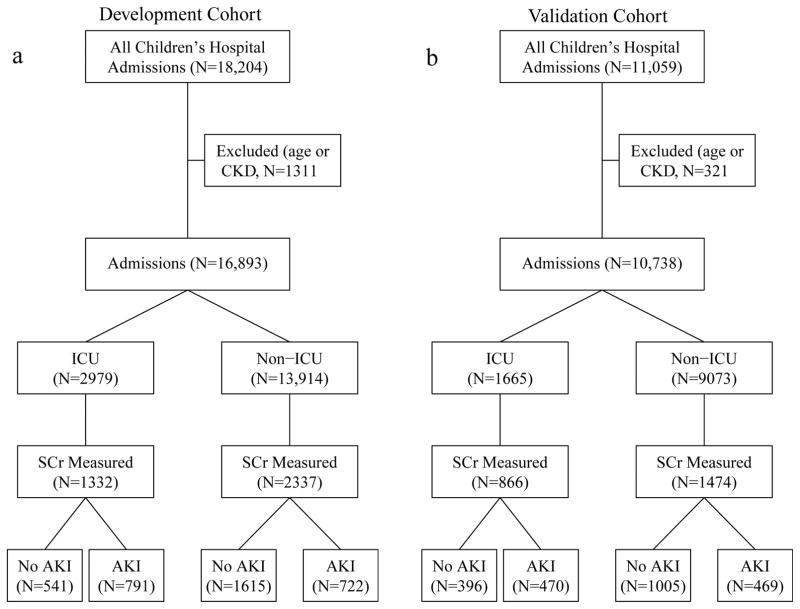

The ICU development cohort included 1332 admissions (Figure 1 a) of patients with care in the ICU during any portion of the hospitalization and creatinine measurements available for outcome determination. Median age was 4.4 (IQR 0.9–12.0) years, and the majority of patients were male (N=724, 54%) and White (N=1025, 77%, Table 1). In this critically ill cohort, 791 (59%, Figure 1 a) met criteria for AKI, defined as a serum creatinine increase of ≥0.3 mg/dL or an increase of ≥1.5-fold from baseline.(7) Of the 791 patients with AKI, 351 (44%) had Stage 1, 299 (38%) Stage 2, and 141 (18%) Stage 3. The evaluated serum creatinine was obtained 0.3 (IQR 0.0–0.9) days after admission order for AKI cases and 0.9 (0.4–1.5) days in no-AKI controls (p<0.001). In the 72 hours prior to the evaluated creatinine, those with AKI had lower minimum platelet counts, higher median RDW, lower minimum pH, and younger ages (Table 2). Those with AKI also had fewer total medication exposures and fewer high risk nephrotoxic medication exposures, but more moderate risk nephrotoxins during that time.

Figure 1.

Identification of cases and controls for development and validation cohorts. a) Patient encounters including intensive care (ICU patients) and without intensive care (non-ICU patients) identified for inclusion in the development cohort. b) Patient encounters including intensive care (ICU patients) and without intensive care (non-ICU patients) identified for inclusion in the validation cohort. AKI – acute kidney injury; CKD – chronic kidney disease; ICU – intensive care unit; SCr – serum creatinine.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and predictive model variables in the 24 hours prior to and 48 hours after admission.

| ICU | Non-ICU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Development (1332) | Validation (866) | Development (2337) | Validation (1474) | |

|

| ||||

| Age (years)a | 4.4 (0.9–12.0) | 5.2 (0.9–12.5) | 8.9 (2.6–14.8) | 9.7 (3.0–14.6) |

|

| ||||

| Maleb | 724 (54) | 495 (57) | 1264 (54) | 750 (51) |

|

| ||||

| Raceb,c | ||||

| White | 1025 (77) | 667 (77) | 1804 (77) | 1115 (76) |

| Black | 205 (15) | 130 (15) | 391 (17) | 249 (17) |

| Other/Unknown | 102 (8) | 69 (8) | 142 (6) | 110 (7) |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic/Latino Ethnicityb | 109 (8) | 65 (8) | 163 (7) | 122 (8) |

|

| ||||

| Number of Inpatient Serum Creatinine Measurementsb | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2–8) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline Serum Creatinine (mg/dL)a | 0.29 (0.21–0.46) | 0.35 (0.24–0.49) | 0.37 (0.24–0.54) | 0.41 (0.28–0.56) |

|

| ||||

| Peak Serum Creatinine (mg/dL)a | 0.51 (0.37–0.77) | 0.55 (0.42–0.77) | 0.50 (0.35–0.70) | 0.56 (0.41–0.71) |

|

| ||||

| Median White Blood Cell Count (×103/μL)a | 11.0 (7.8–15.2) | 10.1 (7.2–14.0) | 9.2 (6.1–13.3) | 9.3 (5.9–13.1) |

|

| ||||

| Hematocrit (%)a | 30 (26–36) | 34 (29–39) | 33 (29–38) | 36 (29–41) |

Median (interquartile range);

Number, (%);

Other includes Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and Unknown. ICU – Intensive care unit.

Table 2.

Serum creatinine values and predictive model variables in development cohort in those with and without AKI

| ICU | Non-ICU | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Non-missing (1332) | No AKI (541) | AKI (791) | P-Value | Non-missing (2337) | No AKI (1615) | AKI (722) | P-Value | |

|

| ||||||||

| Baseline Serum Creatinine (mg/dL)a,b | 1332 | 0.36 (0.26–0.54) | 0.26 (0.19–0.41) | <0.001 | 0.42 (0.29–0.58) | 0.26 (0.18–0.41) | <0.001 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Peak Serum Creatinine (mg/dL)a,b | 1332 | 0.45 (0.31–0.63) | 0.56 (0.42–0.91) | <0.001 | 0.49 (0.34–0.67) | 0.53 (0.37–0.77) | <0.001 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Age (years)a | 1332 | 6.5 (1.4–13.6) | 2.6 (0.6–10.5) | <0.001 | 2337 | 10.6 (3.3–15.3) | 5.3 (2.0–12.4) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| High Risk Nephrotoxinsc | ||||||||

| 0 | 1332 | 428 (79) | 673 (85) | 0.02 | 2337 | 1195 (74) | 634 (88) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 91 (17) | 96 (12) | 311 (19) | 61 (8) | ||||

| ≥2 | 22 (4) | 22 (3) | 109 (7) | 27 (4) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Moderate Risk Nephrotoxinsc | ||||||||

| 0 | 1332 | 452 (84) | 557 (70) | <0.001 | 2337 | 1453 (90) | 671 (93) | 0.01 |

| 1 | 63 (12) | 151 (19) | 136 (8) | 36 (5) | ||||

| ≥2 | 26 (5) | 83 (10) | 26 (2) | 15 (2) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Total Medicationsa | 1332 | 4 (1–7) | 1 (0–9) | <0.001 | 2337 | 1 (0–4) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Minimum Platelet Count (×103/μL)a | 737 | 252 (184–330) | 161 (100–280) | <0.001 | 948 | 267 (198–350) | 234 (141–351) | 0.003 |

|

| ||||||||

| Median Red Cell Distribution Width (%)a | 677 | 13.4 (12.8–14.2) | 13.8 (13.0–14.7) | <0.001 | 953 | 13.3 (12.7–14.7) | 14.5 (13.0–16.3) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||||

| Phosphorusc | ||||||||

| None Checked | 1332 | 485 (90) | 745 (94) | <0.001 | 2337 | 1451 (90) | 666 (92) | 0.04 |

| Normal | 46 (9) | 26 (3) | 122 (8) | 34 (5) | ||||

| High Value | 10 (2) | 20 (3) | 42 (3) | 22 (3) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Transaminasesc | ||||||||

| None Checked | 1332 | 408 (75) | 717 (91) | <0.001 | 2337 | 1191 (74) | 629 (87) | <0.001 |

| Normal | 79 (15) | 23 (3) | 225 (14) | 41 (6) | ||||

| High Value | 54 (10) | 51 (6) | 199 (12) | 52 (7) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Minimum pHa | 962 | 7.30 (7.24–7.36) | 7.25 (7.15–7.30) | <0.001 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Hypotensionc | 1332 | 132 (24) | 241 (30) | 0.02 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Median (interquartile range), p-value from Wilcoxon rank-sum test;

Note that neither baseline nor peak serum creatinine is included as covariates in the predictive model;

Number, (%), p-value from Pearson chi square test. AKI – Acute Kidney Injury; ICU – Intensive Care Unit.

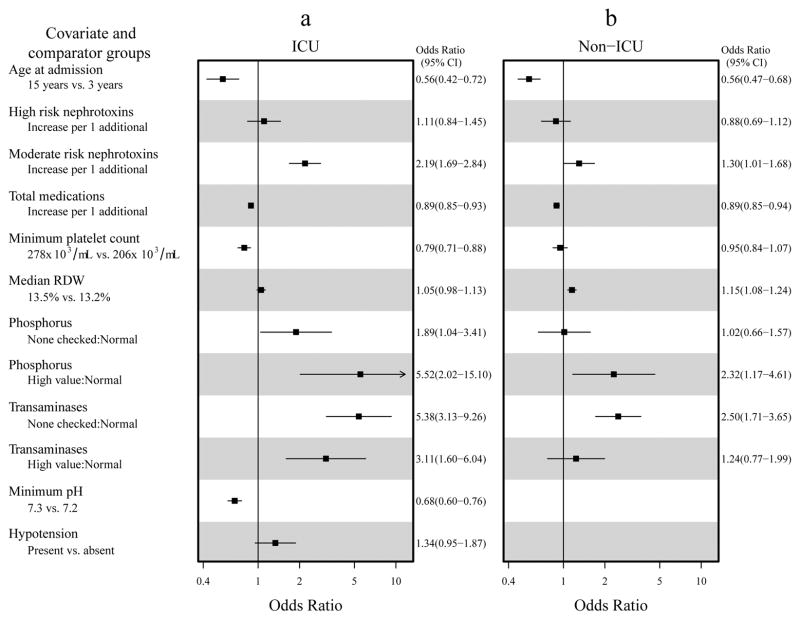

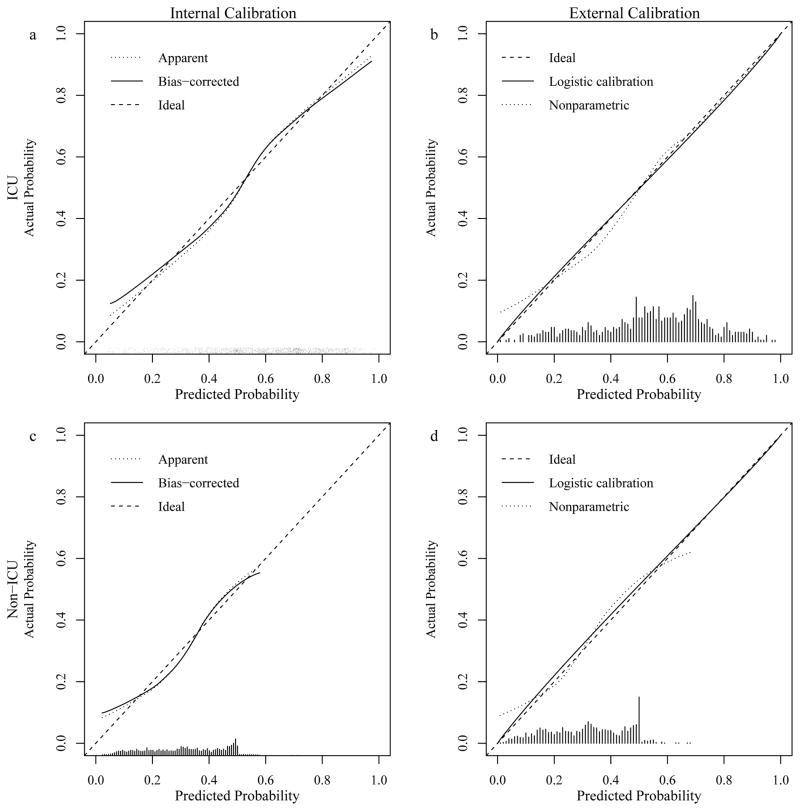

The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the selected predictors for AKI are shown in Figure 2 a. Figure 3 a shows the calibration plot from the development cohort, which demonstrates minimal overfitting and good calibration. Additional details including variable selection, the prediction rule as a linear predictor, and model performance and discrimination metrics from internal validation are in the Supplemental Results, Tables S3–S5, Figure S2, and Supplemental File 1 (online).

Figure 2.

Odds Ratios for individual factors included in the acute kidney injury risk prediction for ICU (a) and non-ICU (b) patients. Odds ratios depicted are for age (15 vs. 3 years at admission), increase in 1 high risk nephrotoxin, increase in 1 moderate risk nephrotoxin, additional 1 total medication, minimum platelet count (278 vs. 206 × 103/μL), median RDW (13.5% vs. 13.2%), highest phosphorus (none checked vs. normal and one or more high value vs. all normal), transaminases (none checked vs. normal and one or more high value vs. all normal), minimum pH (7.3 vs. 7.2, ICU only), and presence vs. absence of hypotension (ICU only). Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each odds ratio are shown to the right of each plot. ICU – Intensive care unit; RDW – red cell distribution width.

Figure 3.

Calibration curves for internal and external validation of acute kidney injury (AKI) models, with predicted probability based on the AKI model on the X-axis, and actual observed probability on the Y-axis. a) Internal calibration curve for intensive care unit (ICU) patients, generated via bootstrapping. b) External calibration curve for ICU patients. c) Internal calibration curve for non-ICU patients, generated via bootstrapping. d) External calibration curve for non-ICU patients.

Model External Validation for ICU Patients

The ICU external validation cohort included 866 patient admissions during the subsequent year, and 470 (54%) met criteria for AKI (Figure 1 b). This cohort was similar at admission to the development cohort with respect to demographics and AKI risk factors (Table 1). For external validation, the predictive rule derived from the development cohort was applied to the validation cohort to calculate predicted probabilities, which were then validated against true patient outcomes by fitting a logistic model. The calibration plot for the external validation data (Figure 3 b) indicated good model fit.

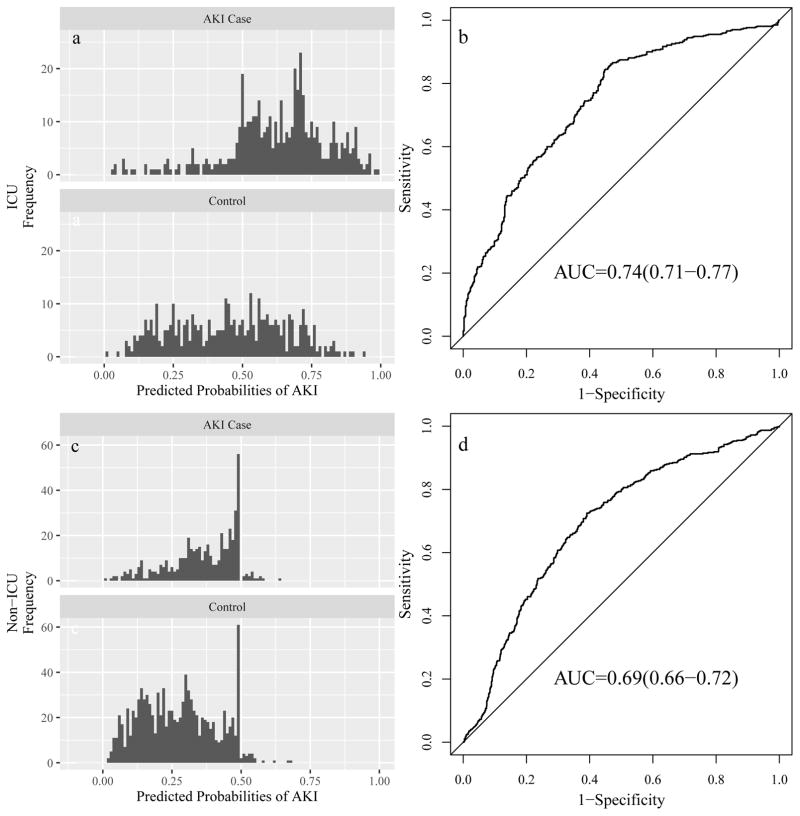

The frequency distributions of model calculated AKI risk among ICU admissions with and without AKI in the validation cohort are shown in Figure 4 a as an indication of model discrimination. Note the overlapping distributions, with those in the ICU who developed AKI with a tendency toward higher predicted probability scores. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the ICU model in the validation cohort is shown in Figure 4 b; the C-statistic, which measures the area under the ROC curve, was 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.71–0.77). The model performance varied by severity of AKI, with a C-Statistic of 0.72 (0.68–0.76) for stage 1 AKI, and increased to 0.76 (0.72–0.8) for stage 2 or 3 AKI. Additional details of the external validation are included in the Supplemental Results and Tables S5–S6 (online).

Figure 4.

Discrimination of acute kidney injury (AKI) models in the validation cohort. a) Frequency distribution of calculated probabilities of AKI in the ICU validation cohort for those with (top panel) and without (bottom panel) AKI. b) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the ICU validation cohort, with risk prediction model sensitivity on the Y-axis and 1-specificity on the X-axis. The area under the curve (AUC), or C-statistic, indicating model discrimination, is 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.71–0.77). c) Frequency distribution of calculated probabilities of AKI in the non-ICU validation cohort for those with (top panel) and without (bottom panel) AKI. d) ROC curve for the non-ICU validation cohort, with risk prediction model sensitivity on the Y-axis and 1-specificity on the X-axis. The AUC (C-statistic) is 0.69 (95% confidence interval 0.66–0.72). ICU – intensive care unit.

Model Development and Internal Validation for Non-ICU Population

The non-ICU development cohort included 2337 admissions with creatinine measurements available for outcome determination, of which 722 (31%) met AKI criteria (Figure 1). Of the 722 with AKI, 443 (61%) had Stage 1, 199 (28%) Stage 2, and 80 (11%) Stage 3. Median age was 8.9 (IQR 2.6–14.8) years, and the majority of patients were male (N=1264, 54%) and White (N=1804, 77%, Table 1). The evaluated serum creatinine was obtained 0.0 (IQR −0.1–0.3) days after admission order for AKI cases and 0.6 (0.1–1.6) days in no-AKI controls (p<0.001). Similar to the ICU cohort, non-ICU patients with AKI were younger, had lower minimum platelet counts, and higher median RDW than those who did not develop AKI. Non-ICU patients with AKI had fewer total, high risk, and moderate risk nephrotoxic medications in the 72 hours preceding their evaluated creatinine measurements as compared to no-AKI controls (Table 2).

The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the selected AKI predictors are shown in Figure 2 b. The internal calibration plot is shown in Figure 3 c, which demonstrated minimal overfitting and good calibration. Additional results from the internal validation are presented in Supplemental Results, Tables S3–S5, Figure S2, and Supplemental File 1 (online).

Model External Validation for Non-ICU Population

The non-ICU validation cohort included 1474 admissions during the subsequent year of which 469 (32%) met criteria for AKI (Figure 1 b). This cohort was similar at admission to the development cohort (Table 1). The calibration plot for the external validation data (Figure 3 d) again indicated good model fit. The frequency distributions of model calculated AKI risk among those with and without AKI in the non-ICU validation cohort is shown in Figure 4 c. The ROC for the non-ICU model in the validation cohort is shown in Figure 4 d; the C-statistic was 0.69 (95% confidence interval 0.66–0.72). Again, the model performance varied by disease severity, with a C-statistic for patients in the validation cohort for those with Stage 1 AKI of 0.66 (0.63–0.7), and 0.74 (0.7–0.77) for those with more severe Stage 2 or 3 AKI. Additional results from external validation are included in the Supplemental Results and Tables S5–S6 (online).

Discussion

We present the development of accurate and reliable risk prediction models that can be used to screen for pediatric AKI in ICU and non-ICU patients based on variables readily available in the EHR. These models will be incorporated into the EHR as part of a randomized trial testing targeted AKI surveillance, a strategy that has been demonstrated to reduce AKI severity in other settings.(13,14) Given the frequency of AKI in children and the associated increases in length of stay, morbidity, and mortality, this work has the potential to save health care dollars and improve clinical outcomes for children. Furthermore, this approach demonstrates a strategy for utilizing EHR data to generate clinically-implementable risk prediction rules which can be employed for alternative clinical outcomes.

The goal of this study was to build predictive models for pediatric AKI. Model covariates are only required to be informative in the model, and are not required to independently predict AKI or have a role in the pathogenesis of the outcome. Each covariate in the model was selected from an a priori set of candidate covariates, and for many the association and odds ratios were as expected. Lower platelet count, lower pH, RDW, and hypotension are known risk factors for AKI.(1,4,6,21,22) One prior study found that younger patients experienced more AKI,(6) while other studies have indicated higher risk in older patients;(1,4) associations of young age to AKI are potentially confounded by the low baseline creatinine in the youngest pediatric patients, leading to AKI diagnosis via 1.5-fold creatinine increase without clinically meaningful reduction in renal function. Other results were unexpected, such as the stronger association of moderate risk nephrotoxins than high risk nephrotoxins to AKI, which may be due to clinicians avoiding known nephrotoxic medications in children with suspected renal insufficiency. Fewer high risk nephrotoxins and total medications may result from the very early presentation of many cases of AKI (e.g. on admission) prior to medication administration and the earlier measurement of creatinine in AKI cases vs. no-AKI controls; however, ICU patients with AKI had increased rate of exposure to moderate risk nephrotoxins, indicating that we are capturing medication exposures. We also found that for the categorical variables (phosphorus and transaminases), unchecked or missing values were associated with an increased risk of AKI vs. normal/low values. This indicates that AKI was overrepresented in patients where these laboratory measurements were not performed as part of clinical care, relative to those with measured values within normal limits. This may indicate that patients with normal values are at lower risk for AKI due to more benign presentation of disease. Patients in whom these laboratory measurements are not routinely performed may be a group with relatively high incidence of AKI. However, these statistical correlations do not imply causation, and our study was not designed to identify independent risk factors or etiologies for pediatric AKI. Importantly, changes in clinical practice (e.g. a sharp increase in testing of transaminases or phosphorus) would require recalibration of the model, as calculated (but not true) AKI risk would be affected. A demonstration calculator incorporating model covariates is available (Supplemental File 2 (online)) and can be used to show the relative impact of changes in each predictor.

While the AKI outcome is defined by change in creatinine, we intentionally designed these risk prediction models for AKI to perform well prior to ascertainment of creatinine and associated results such as blood urea nitrogen (BUN), potassium, and calcium. Notably, a risk prediction model for early AKI in a pediatric ICU including BUN, pH, platelet count, total bilirubin, age, post-operative status, and pre-admission cardiac arrest had a C-statistic of 0.76–0.86 in validation sets, similar to performance of our models.(21) At our institution, pre-admission cardiac arrest and post-operative status are not available for incorporation into real-time prediction in our EHR, so these were not included. Furthermore, we developed a parallel predictive model for non-critically ill patients, an important advancement as these patients have less frequent laboratory monitoring and less rigorous assessment of urine output making early clinical detection of AKI more difficult.

Given the goal of early AKI detection, Stage 1 AKI criteria was used, defined using the KDIGO creatinine criteria, the current clinical standard.(23) The KDIGO criteria also include time windows for the increase in creatinine (i.e., increase by 0.3 mg/dL or more within 48 hours or 1.5-fold increase in 7 days), which were not enforced in our cohort, as this restriction could introduce significant bias as only those with suspected renal injury would have frequent monitoring. In all, 187 of the 939 patients with AKI in the validation cohort had an increase of 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours, and 617 had 1.5-fold increase of creatinine within 7 days of the baseline, indicating that a majority of the cohort satisfied these criteria; however, the inclusion of patients who did not meet the time window requirements may impact the validity of our models in detecting AKI meeting formal KDIGO criteria.

Our development cohorts included data from the most recent admission for every patient hospitalized over a two-year period in our tertiary referral children’s hospital pediatric ICU and non-ICU with baseline and an additional inpatient creatinine measurement. Since creatinine is measured as part of a panel obtained for a wide variety of reasons and not only due to suspicion of AKI, this cohort remains adequate to represent the patient population as a whole. However, patients with no creatinine measurements likely have systematically lower AKI risk, resulting in over-estimation of AKI risk. Given our goal of using the EHR-based models as a screening tool to identify those at-risk for follow up testing via serum creatinine measurement, risk over-estimation is preferred. However, the generalizability of our model cannot be proven without serial prospective assessment of serum creatinine in a representative cohort of pediatric patients.

The next step in translating this work is clinical implementation of the model to determine the impact of real-time AKI risk prediction. Previous prediction strategies have demonstrated benefits of early AKI detection. EHR-based screening for nephrotoxic medication exposures in pediatric inpatients at a tertiary pediatric hospital resulted in a 42% reduction in AKI intensity.(13) In further work targeting cystic fibrosis patients exposed to aminoglycosides, daily serum creatinine measurement was associated with shorter aminoglycoside courses, fewer concomitant aminoglycosides, and earlier detection of AKI.(14) In a randomized trial in adults, text paging providers and pharmacists if their patient met AKI criteria failed to demonstrate efficacy in improving the clinical outcomes of maximum change in serum creatinine, dialysis use, or mortality.(24) These limited data indicate that early detection of AKI through targeted screening, not just clinician notification of AKI status, may be required to improve patient outcomes. Our risk prediction model can enable such early detection across all admitted pediatric patients, including those who are not exposed to nephrotoxic drugs or do not belong to a specific high-risk subset of patients. Given the early diagnosis of AKI in our cohort (often on admission), the risk prediction models may be most useful in identifying at-risk patients very early in their hospital course, providing the opportunity for early detection and intervention.

Our development of risk prediction models for incorporation into EHRs has several limitations. In building predictive models, covariates are not required to be independent or causative, so any associations with the outcome do not inform mechanistic insights into pediatric AKI. As discussed above, our defined outcome of AKI is limited to changes in creatinine measurement. This restricts our retrospective cohort to those patients with sufficient creatinine data available for assigning AKI status. Due to the sparse availability of baseline creatinine measurement preceding the inpatient admission for pediatric patients, the KDIGO time windows for change in creatinine were not enforced, and the baseline measurement may have been measured after the AKI event (indicating return to normal renal function). This strategy was employed to reduce the potential bias from including only those individuals with serum creatinine measurement available prior to any injury. Furthermore, we did not differentiate between community-acquired and hospital-acquired AKI; indeed, many of our AKI cases were detected upon admission, and it is difficult to assess risk factors prior to admission. These issues may affect the validity of the models and the ability to accurately predict AKI that develops later in the hospital admission. Future work that includes more sensitive or specific biomarkers for renal injury, assayed across a broad spectrum of patients, may improve the precision and accuracy of AKI risk prediction modeling, as will sub-phenotyping the outcome (e.g. AKI on admission vs. early-AKI vs. late-AKI). We pre-specified that patients admitted to the ICU during their admission would remain in the ICU cohort, but these patients’ AKI risk may be better predicted using the floor model after transfer; additional data collection will enable testing of this hypothesis. Our external validation was performed using a distinct set of admissions (temporal validation), but did not assess model performance in another pediatric institution (geographic validation). Implementation in a different population should be preceded by validation and calibration in the target population. Finally, performance metrics indicate that while our model is stable across internal and external validation, model discrimination is modest. Cut points with high sensitivity for AKI have low specificity, especially for the non-ICU model (e.g., at 30% AKI risk, the non-ICU model is 74% sensitive but only 58% specific, Table S6 (online)). To be an effective screening tool for AKI, high sensitivity is required, and low specificity is acceptable since a low-risk follow up test is available. In this scenario, modest AKI risk prediction can trigger advice to check creatinine, the current diagnostic test for AKI.

Conclusions

Through analysis of admissions to this pediatric hospital, we generated and validated statistical predictive models for AKI using data routinely collected and available from EHRs. These risk prediction models can be incorporated into clinical practice from within EHRs as a screening tool to alert providers of increased risk for AKI among children in ICU and non-ICU cohorts, especially at the time of admission. Our approach demonstrates use of the EHR to promote a learning healthcare system by using EHR data in generating clinically implementable risk prediction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ioana Danciu, M.S., from the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research for her contribution to the planning and data acquisition for this work, Jeffrey A. Byrd from Vanderbilt University Medical Center Health Information Technology for his assistance in the execution of this work, and Frank E. Harrell, Jr., Ph.D. from the Vanderbilt Department of Biostatistics for his guidance in the planning and execution of this work.

Statement of Financial Support: The project described was supported by CTSA award UL1 TR000445 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the NCATS or the National Institutes of Health (NIH). SLV is supported by NIH/NCATS KL2 TR000446. TLM was supported by NIH/National Institute of Child Health and Development K23 HD000001.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Sutherland SM, Ji J, Sheikhi FH, et al. AKI in hospitalized children: epidemiology and clinical associations in a national cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2013;8:1661–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00270113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akcan-Arikan A, Zappitelli M, Loftis LL, Washburn KK, Jefferson LS, Goldstein SL. Modified RIFLE criteria in critically ill children with acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2007;71:1028–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGregor TL, Jones DP, Wang L, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Incidence in Noncritically Ill Hospitalized Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults: A Retrospective Observational Study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:384–90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey D, Phan V, Litalien C, et al. Risk factors of acute renal failure in critically ill children: A prospective descriptive epidemiological study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:29–35. doi: 10.1097/01.pcc.0000256612.40265.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moghal NE, Brocklebank JT, Meadow SR. A review of acute renal failure in children: incidence, etiology and outcome. Clin Nephrol. 1998;49:91–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selewski DT, Cornell TT, Heung M, et al. Validation of the KDIGO acute kidney injury criteria in a pediatric critical care population. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1481–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int. 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkandari O, Eddington KA, Hyder A, et al. Acute kidney injury is an independent risk factor for pediatric intensive care unit mortality, longer length of stay and prolonged mechanical ventilation in critically ill children: a two-center retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15:R146. doi: 10.1186/cc10269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soler YA, Nieves-Plaza M, Prieto M, García-De Jesús R, Suárez-Rivera M. Pediatric Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-Stage renal disease score identifies acute kidney injury and predicts mortality in critically ill children: a prospective study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:e189–195. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182745675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaddourah A, Basu RK, Bagshaw SM, Goldstein SL AWARE Investigators. Epidemiology of Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Children and Young Adults. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:11–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piccinni P, Cruz DN, Gramaticopolo S, et al. Prospective multicenter study on epidemiology of acute kidney injury in the ICU: a critical care nephrology Italian collaborative effort (NEFROINT) Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:1072–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider J, Khemani R, Grushkin C, Bart R. Serum creatinine as stratified in the RIFLE score for acute kidney injury is associated with mortality and length of stay for children in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:933–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cd12e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein SL, Kirkendall E, Nguyen H, et al. Electronic Health Record Identification of Nephrotoxin Exposure and Associated Acute Kidney Injury. Pediatrics. 2013 Sep;132(3):e756–67. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downes KJ, Rao MB, Kahill L, Nguyen H, Clancy JP, Goldstein SL. Daily serum creatinine monitoring promotes earlier detection of acute kidney injury in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2014 Jul;13(4):435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James MT, Hobson CE, Darmon M, et al. Applications for detection of acute kidney injury using electronic medical records and clinical information systems: workgroup statements from the 15(th) ADQI Consensus Conference. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2016;3:9. doi: 10.1186/s40697-016-0100-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutherland SM, Chawla LS, Kane-Gill SL, et al. Utilizing electronic health records to predict acute kidney injury risk and outcomes: workgroup statements from the 15(th) ADQI Consensus Conference. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2016;3:11. doi: 10.1186/s40697-016-0099-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colantonio DA, Kyriakopoulou L, Chan MK, et al. Closing the gaps in pediatric laboratory reference intervals: a CALIPER database of 40 biochemical markers in a healthy and multiethnic population of children. Clin Chem. 2012;58:854–68. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.177741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danciu I, Cowan JD, Basford M, et al. Secondary use of clinical data: the Vanderbilt approach. J Biomed Inform. 2014;52:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies with Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag New York, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Pinto LN, Khemani RG. Development of a Prediction Model of Early Acute Kidney Injury in Critically Ill Children Using Electronic Health Record Data. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016 Jun;17(6):508–15. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SW, Yu M-Y, Lee H, et al. Risk Factors for Acute Kidney Injury and In-Hospital Mortality in Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. PloS One. 2015;10:e0140674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devarajan P. Biomarkers for the early detection of acute kidney injury. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:194–200. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328343f4dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson FP, Shashaty M, Testani J, et al. Automated, electronic alerts for acute kidney injury: a single-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1966–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60266-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.