INTRODUCTION

This note engages in the public debate over the participation of female athletes with hyperandrogenism in professional sport. Hyperandrogenism, a condition leading to higher testosterone levels than would be expected for ‘biological females’, is thought by many to provide affected athletes with a competitive edge over non-affected athletes.1 In 2011, when public attention was drawn to runner Caster Semenya, international sporting organizations implemented policies to monitor testosterone levels in female athletes as part of traditional ‘sex testing’.2 The new policy required that female athletes have a testosterone level under 10 nmol/L in order to be eligible to compete as female, and recommending that athletes with higher testosterone levels seek medical advising for further treatment.3

The new policy was criticized for essentially expelling hyperandrogenic athletes from participating in professional sports unless they undergo dramatic medical modifications, and was recently suspended temporarily by the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) after runner Dutee Chand refused to regulate her testosterone levels in order to compete as a female.4 The CAS decision reenergized the cultural and scientific testosterone debate, and was marked by the introduction of new arguments regarding whether or not the testosterone rule serves the objective of ‘fairness’ in sports.

After briefly reviewing the historical origins of the testosterone rule and sex testing in organized sport, this note describes existing scientific data and its interpretations regarding sex. While maintaining that the relationship between a high testosterone level and athletic performance has not been proven, but also not refuted, the last part offers preliminary thoughts on three alternative approaches to achieve fairness in sports.

I. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE TESTOSTERONE RULE

A. The formation of the testosterone rule

Professional sports bodies have been troubled by the difficult issue of sex classification for many years.5 Testing for sex was first enforced by the International Olympics Committee (IOC) in 1968. This practice was implemented in order to mitigate anxieties at the time that Soviet male athletes would compete as females to increase the Communist medal count, but also to relax older and more cultural worries of masculinization of women in sport.6 However, these sex classification tests were never simple to administer nor very reliable. Initially, female athletes were required to expose their bodies for physical scrutiny by examiners; however, mounting complaints led the IOC to employ a chromosomal test instead.7 The first athlete to challenge these tests was Spanish hurdler Maria Patino, whose examination in 1988 by the Olympics’ ‘Femininity Control Head Office’ resulted in the discovery of a Y chromosome.8 Patino had androgen insensitivity syndrome, a condition in which the cells are not receptive to testosterone.9 Although she was born with a Y chromosome, leading to the development of testes and the manufacturing testosterone and estrogen, her body reacted solely to the estrogen she produced and therefore developed in a feminine form (breasts, round hips, etc.). Patino lived her entire life as a woman and had the strength traditionally expected of women, but was banned from participating in the 1988 Olympics. Although she was allowed to compete a few years later, the IOC continued to insist that even if the Y chromosome was found to be an unreliable criterion for sex testing, some form of testing must be done.10

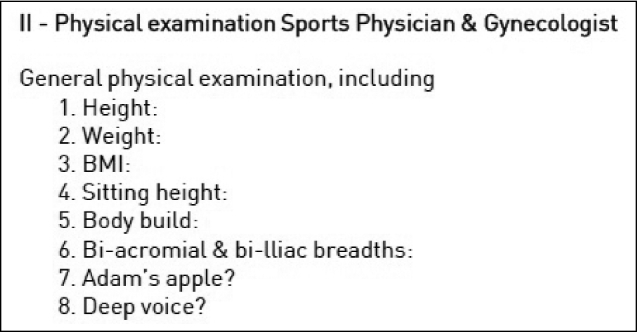

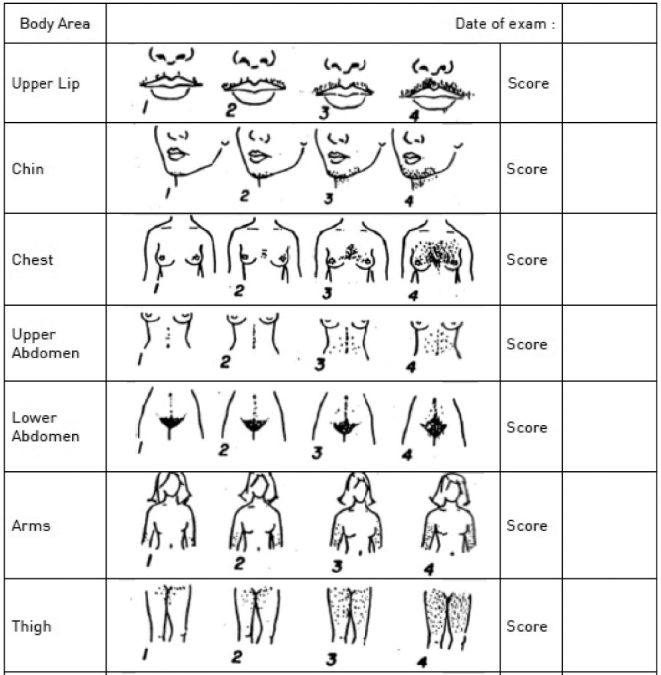

The recent controversy regarding sex verification tests in professional sport was tied to a different dominant biological sex marker: hormone levels, particularly testosterone. After the domination of South African runner Caster Semenya in the 2009 Track and Field World Championship, during which many suspected that she was a man, or not biologically female,11 the International Association of Athletes Federation (IAAF) decided to institute new regulations regarding hormone levels for athletes, aimed to prevent a reoccurrence of the Semenya case.12 The new policy, issued in 2011 after 18 months of expert consultation, targeted women with hyperandrogenism, defined therein as a physical condition leading to ‘excessive production of androgens (testosterone)’.13 The 2011 IAAF policy maintained that ‘the difference in athletic performance between males and females is known to be predominantly due to higher levels of androgenic hormones in males resulting in increased strength and muscle development’.14 Continuing the desire to preserve ‘fair’ competition that led to the sex separation in competition in the first place, the regulations proposed a three-stage diagnosis. The first is an initial clinical examination which requires taking a medical history and a physical examination.15

IAAF Regulation, Appendix 2: Medical Guidelines for the Conduct of Level 1 and Level 2 examinations (2011) http://www.bmj.com/sites/default/files/response_attachments/2014/06/IAAF%20Regulations%20(Final)-AMG-30.04.2011.pdf (accessed Jan. 17, 2017).

The second level is a preliminary endocrine assessment, requiring blood and urine samples to be analysed for specific types of androgenic hormones.16 If the first and second-level examinations reveal preliminary signs of aberrant presentation compared to what would be expected for a biological female, the athlete is referred to the third level: a full examination, which includes further genetic and hormonal laboratory work.17 After all data are collected, an expert medical panel determines whether or not the athlete is eligible to compete based on the athlete's androgen levels.18 The normal range for males is defined in the regulations as ‘more than 10 nanomoles per litre’ (10 nmol/L). If athletes are past this threshold, they cannot compete as female, regardless of other aspects of their biological presentation.19

Hirsutism scoring sheet according to Ferriman and Gallwey, IAAF Regulation, Appendix 2: Medical Guidelines for the Conduct of Level 1 and Level 2 examinations (2011) http://www.bmj.com/sites/default/files/response_attachments/2014/06/IAAF%20Regulations%20(Final)-AMG-30.04.2011.pdf (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

B. Conflicting decisions regarding the testosterone rule

More recently, two conflicting decisions alternatively undermined and restored the testosterone rule in professional sport. The first decision was given by the CAS in favor of Dutee Chand, an Indian sprinter who was banned from competing as a female due to her high androgen levels. Chand, apparently diagnosed with hyperandrogenism, was initially required to undergo normalizing medical procedures, hormonal or surgical, which would decrease her natural testosterone levels to the permissible range.20 In her letter to the IAAF Chand wrote:

The high androgen level produced by my body is natural. I have not doped or cheated. If I follow the IAAF guidelines you have attached, I will have to undergo medical intervention in order to reduce my naturally produced androgen levels. […] I feel perfectly healthy and I have no health complaints, so I do not want to undergo these procedures […] I also understand that these interventions will most likely decrease my performance level because of the serious side effects and because they will interfere with the way my body has worked my whole life.21

Chand appealed the Athlete Association of India and IAAF’s joint decision to ban her from participating in competitions, and received a landmark ruling in her favor in July 2015. The CAS decided that hyperandrogenism regulations were discriminatory toward women, and based on insufficient scientific evidence. Although all parties agreed that lean body mass (LBM) affects athletic performance, they could not agree on the influence of testosterone on LBM.22 So although Chand hadn’t firmly established that ‘testosterone is not a material factor in determining athletic performance’,23 the evidence brought by the IAAF to support the link between testosterone levels and athletic performance referred only to exogenous testosterone (externally consumed), and not endogenous testosterone (naturally produced),24 and did not refute her claim in full. The panel concluded that the IAAF had not established that hyperandrogenic females have an unfair advantage or that they perform better due to their naturally high testosterone levels.25 Therefore, ‘the panel [was] unable to uphold the validity of the regulations’, and suspended the testosterone rule for a period of 2 years to allow the IAAF an opportunity to gather supporting evidence concerning the influence of endogenous testosterone levels on LBM and athletic performance.26

**

The second relevant decision came in November 2015 from the IOC Consensus Meeting on Sex Reassignment and Hyperandrogenism. Understanding the growing importance in recognizing gender identity, the statement was intended to liberalize eligibility rules for the participation of transgender athletes while still preserving the objective of ‘fair competition’.27 The updated institutional policy no longer required surgical modification for athletes to complete.28 Instead, the consensus instructed that female to male transitioning athletes will be able to compete in the male category with no restrictions, while male to female (MTF) athletes will have to ‘demonstrate that her total testosterone level in serum has been below 10 nmol/L for at least 12 months prior to her first competition’.29

This consensus statement largely liberalized eligibility requirements regarding surgery for transgender athletes. Yet it also reinforced the testosterone rule as the demarcating criteria between the sexes to constitute fairness between athletes in the same sex category, contrary to the CAS decision in Dutee Chand's case. The IOC addressed the contradiction directly and encouraged the IAAF to ‘revert to CAS with arguments and evidence to support the reinstatement of its hyperandrogenism rules’.30 The meeting proposed allowing females with hyperandrogenism to compete as males as a solution to discrimination.31

II. DOES TESTOSTERONE PROVIDE A COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE?

Policymakers dealing with this topic usually refer to the only empirical evidence available: two large-scale studies conducted in 2014 designed to measure the hormonal profiles of elite athletes. But these studies yielded somewhat conflicting results. One study, often referred to as GH-2000, was a ‘spin-off’ from a project designed to trace abuse of growth hormone in sport.32 By the end of the original experiment (conducted in 2012 during the London Olympics), there was sufficient serum for the study of hormonal profiles of 693 elite athletes.33 The blood samples were drawn from 454 males and 239 female athletes in 15 competition categories within two hours of their competition. Results showed that contrary to what researchers had expected, there was a substantial overlap in testosterone levels between the sexes, as 16.5 per cent of males demonstrated low testosterone levels (under 8.4 nmol/L, the lower limit of the normal reference range for males), whereas 13.7 per cent of females demonstrated high testosterone levels (above 2.7 nmol/L, the upper limit of the normal reference range for females).34 However, the most distinctive criterion in differentiating between male and female athletes was their LBM,35 as the research established that females have 85 per cent of the LBM of males.36 Researchers believe that these findings are sufficient to account for ‘observed differences in strength and aerobic performance’ between male and female athletes, ‘without the need to hypothesize that performance is in any way determined by the differences in testosterone levels’.37 The researchers additionally suggest that the findings ‘negate completely the hypothesis concerning testosterone levels proposed by IAAF/IOC’.38 The authors conclude that hormonal profiles of elite athletes differ from the usual reference range, and that ‘the IOC definition of a woman as one who has a normal testosterone level is untenable’.39

The other study, commissioned by the IAAF and conducted at the 2011 IAAF Track and Field World Championships in Daegu, South Korea, is referred to as the Daegu study.40 This study measured testosterone levels among 849 female athletes, with a goal to estimate the prevalence of hyperandrogenism and other disorders of sex development (DSD) among high-level female athletes.41 Results demonstrated that median testosterone levels among elite female athletes were similar to those of non-athlete healthy young females (0.69 nmol/L median found in sampled athletes), with the 99th percentile calculated at 3.08 nmol/L.42 Out of 839 women tested, 9 had testosterone levels greater than 3 nmol/L, and 3 women had levels above 10 nmol/L.43 Despite the plausible speculation that high-level athlete women would demonstrate higher testosterone levels than their non-athlete counterparts, this hypothesis was not confirmed in the data.44 On the other hand, the researchers argued that although the link between testosterone levels and athletic performance had not been directly tested, the much higher prevalence of hyperandrogenic females among high-level athletes relative to the general population (approximately 140 times higher in this study), may be ‘indirect evidence for performance-enhancing effects of hyperandrogenic DSD concentration in female athletes’.45 The next sections will demonstrate how the two studies have been received and interpreted by both sides to the debate.

A. Natural testosterone levels do not provide a competitive edge, and therefore hyperandrogenic female athletes should compete as women

Some of the most vocal defenders of the position that higher testosterone levels do not provide a competitive advantage are Katarina Karkazis, an anthropologist and bioethicist from the Center for Biomedical Ethics at Stanford University, and Rebecca Jordan-Young, the author of ‘Brain Storm: The Flaws in the Science of Sex Differences’. In 2012, after the IAAF and IOC published their new policies on hyperandrogenism, Karkazis and Jordan-Young argued that despite common belief, the relationship between endogenous testosterone and athletic advantage is not scientifically proven, and moreover, would be very hard to establish due to the complex set of reactions different individuals have to similar doses of testosterone.46 Their paper offered instead the imperfect, yet preferred criterion of ‘legally recognized females’ to determine who could compete in the female category.47

After the two empirical studies were published, Karkazis and Jordan-Young took issue with the Daegu study.48 Their main criticism concerned the fact that the Daegu study sample excluded 10 women, 5 due to doping and the other 5 due to DSD conditions. Karkazis and Jordan-Young argued that the decision to exclude the five women who demonstrated naturally high testosterone levels from the sample resulted from the misconceived judgement of women with DSD as non-healthy and an abnormal ‘confounding factor’. They stated that their exclusion created a circular reinforcement of the object that requires proof, designing the sample to measure normalcy according to the pre-assumed values of what normal is.49 They also replied to critics of the GH-2000 study who argued that the test overestimated testosterone levels at lower ranges and that the decision to draw the serum within two hours from the competition was a mistake in light of data suggesting that male testosterone levels change in response to competition.50 Karkazis and Jordan-Young argued in response that even if the test overestimated the testosterone levels of female athletes, this flaw would not account for low levels of testosterone for male athletes, and therefore the overlap in the GH-2000 study is not refuted. Regarding timing, the authors referenced other studies representing the broad position in the scientific literature suggesting that it is the ‘type and duration’ of competition and not the individual's sex that influence testosterone levels after a competition.51 Karkazis and Jordan-Young proposed that the criterion for ‘female’ athlete competition should probably be LBM and not testosterone levels, as suggested by the GH-2000 study.52

Following headlines and media coverage of the Dutee Chand case, other influential commentators, such as the editors of Scientific American, provided Karkazis and Jordan-Young support by affirming that ‘there is no evidence that they enhance performance’ and that ‘this ongoing state of limbo is a mistake. There is no scientific basis for barring these women’.53

B. Testosterone levels do provide a competitive edge, and therefore hyperandrogenic athletes should not be allowed to compete as women

Karkazis and Jordan-Young stand in contrast to David Epstein, author of ‘The Sports Gene’54, and Alice Dreger, professor of clinical medical humanities and bioethics and author of ‘Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex’,55 who responded to Karkazis and Jordan-Young arguing that they misrepresented the current state of science by relying on the GH-2000 study. Epstein and Dreger instead suggested that the GH-2000 study was not sufficiently credible because it was originally designed to research antidoping; the serum samples were taken post-competition; and samples were taken from variable sports.56

Epstein and Dreger argue that testosterone does provide a competitive advantage. Epstein attributes many physical features to testosterone which are commonly assumed to provide athletic advantage: height, size of limbs, fat mass, etc.57 Epstein then cites a conversation he had with Dreger: ‘…in many sports, the best female athletes can’t compete with the best male athletes. And everybody knows that, but nobody wants to say it. Females are structured like a disabled class for… good reasons’.58 Their belief that a possible overlap in testosterone levels between sexes should not constitute an obstacle to the argument that a relationship between testosterone levels and athletic capacity exists is additionally supported by leading geneticist Eric Vilain, who said that ‘it does not matter whether there is some overlap [of testosterone levels between males and females] or no overlap at all… What matters is, what is the best marker to use to set men apart from women’.59

III. RECONSTRUCTING FAIRNESS

What criteria should matter when we draw lines between groups of athletes, and what would best serve the principle of fairness? Whose opinion should determine what is equal and right? IAAF and IOC? Dutee Chand and Caster Semenya? Epstein and Dreger or Karkazis and Jordan-Young? Fairness can be constructed in various ways, based on a multitude of criteria regarding athletic capacity, biological, social, financial factors, etc. It seems inevitable that every configuration of fairness in sports will seem right and equal to some and not to others, and will necessarily lead to a different distribution of costs and benefits for stakeholders. To conclude, I will suggest preliminary thoughts on alternative classification systems for competitions in sport that prioritize biological and social fairness and elaborate on some of the costs and benefits that groups involved in the debate might experience with these systems.

A. Keep male–female categories, but follow gender identity

Some have suggested that gender identity should be the conclusive criteria instead of testing ‘biological sex’, or at least should determine the result in questionable cases.60 Using the gender identity criterion would mean that women with hyperandrogenism would be allowed to compete as women, including MTF transgender athletes, with no regulation of their testosterone levels. If we think that testosterone levels do not provide a competitive advantage, then there should be no problem with this rule. But if we think that high testosterone levels indeed provide a competitive advantage, then this proposal means women with lower testosterone levels, particularly those at the bottom of the testosterone scale, would be adversely affected by the new policy, whereas MTF transgender athletes and hyperandrogenic women would benefit from it. We do not know, however, what degree of harm and benefits this would confer, as the relationship between testosterone level and athletic capacity has not yet been fully measured.

But even those who believe that higher testosterone levels lead to better athletic capacity might still support a gender rule, even at the price of ‘sacrificing fairness’, on the grounds of respecting individual liberty to identify as one sees fit. Alice Dreger suggested that this could be a solution, even if it isn’t ‘fair’: ‘If we are going to say that people get to be divided by gender, and we take gender seriously, then we let people play according to their gender, not according to biological haves or have-nots’.61

B. Neglect male–female categories for a better biological indicator

This criterion accepts that ‘sex’ is a problematic and unstable biological category, but more importantly, an ambiguous proxy for achieving fairness. What, then, would be a better biological criterion that would maximize fairness? According to the IAAF/IOC, it should be testosterone level. A less controversial biological marker could also be LBM, as presented by the GH-2000 study and supported by the vocal critics of the testosterone rules. In any case, it seems that any agreed biological criteria would still be divisive, and individuals would be separated according to predefined ranges of biological features.

For testosterone level to become the new organizing principle, we would need to understand first how to create new ‘fair’ groups: what is the range of testosterone levels that keeps athletes within a similar level playing field? But even if that goal is achieved, a new biological criterion might lead to a new organization just in part, as these so-called nuanced biological indicators are extracted from and attempt to better distinguish between existing male/female categories. Thus, it makes sense that even a division according to a more ‘accurate’ biological marker would probably preserve a strong male/female dominancy in each group with some ‘outliers’ in the close margins.

If we divide by testosterone level, this means that women with high natural levels (due to hyperandrogenism or otherwise) might find themselves competing in the group with higher testosterone level athletes, mostly men. If we show that testosterone levels indeed provide a competitive edge, this group of female athletes, who used to be at the head of their category, would be adversely affected by such a policy. Additionally, if we take seriously the best male vs. best female obstacle, such a policy can make the prospects of a women winning first place in the upper testosterone level group close to zero. Similarly, some men with naturally lower testosterone levels might find themselves competing in the lower testosterone level group. They might benefit from having easier access to the first places, but would probably be harmed from moving to the lower ranked group which consists of mostly women and hence likely to be, sadly, less prestigious.62 MTF transgender athletes and athletes with hyperandrogenism benefit from the policy in that they would be spared the adverse consequences of being subjected to medical monitoring and control of their natural testosterone levels. But it is less clear whether they would benefit or lose in terms of competition status as we cannot know in which group they would be situated.

C. Start over

One of the strongest arguments against the IAAF and IOC regulation is that even if we accept that high testosterone levels provide a competitive edge, why of all physical traits does testosterone get utmost importance? Karkazis and Jordan-Young say that ‘hyperandrogenism should be viewed as no different from other biological advantages derived from exceptional biological variation’,63 and list documented biological conditions that provide an advantage in certain sports, like runners and cyclists who have rare mitochondrial variations that give them unusual aerobic capacity; basketball players with acromegaly, a hormonal condition leading to large hands and feet, etc.64 Scientific American editors also asserted that ‘elite athletes are by definition physiological outliers because of their strength, speed and reflexes. Natural hormonal variations, similar to other intrinsic biological qualities—superior oxygen-carrying capacity in the blood, for example—are part of that mix. The IOC should say so explicitly’.65

The counter argument to this is that women with hyperandrogenism should not be able to compete in the female category because females are a protected group. According to that logic, ‘Semenya's difference puts her outside the protected athletic category of “woman”—and that makes it unfair to the other runners if she is allowed to compete’.66 Another argument, sometimes made sarcastically, is that these were the lines we have already decided upon as the rules of the game, and that looking to fine biological variations would be absurd. As a Professor of pediatrics said: ‘to start breaking down sport classifications by specific biological traits, ‘you’d have to run international competitions like the Westminster dog show, with competitions for every breed”’.67

But is it so farfetched indeed? Looking at the detailed and bifurcated classification system of the Paralympics by the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) suggests that such a classification can indeed be applied successfully. The IPC classification code takes into consideration the type of impairment, the degree of the impairment, and the psychical activities required for a particular sport, in an algorithmic combination of factors.68 In order to be eligible to compete in the Paralympics, an athlete has to have at least one eligible impairment from the list provided by the IPC, such as impairment in muscle power, range of movement, leg length difference, etc. Under this criterion, some sports are not open to all impairments. For example, while Goalball is open only to visual impairment, swimming is open to all impairments. Another important criterion of eligibility is the degree of impairment, called the ‘minimum impairment criterion’. This requires that the impairment impacts the athlete's sport performance.69 Then every athlete can be assigned to a ‘sport class’, a category that ‘groups athletes depending on how much their impairment impacts performance in their sport’,70 specifically tailored for each sport. Each class can have athletes with different impairments, but all need to have comparable effects on their performance, a conclusion that is decided upon by trained and certified classifiers who use a point system. Swimming, a category open to all eligible impairments, has 10 different ‘sport classes’ that group athletes with various impairments that have a similar activity limitation in swimming, taking into consideration issues such as arm and leg movement and strength, muscle power, trunk control, etc.71 Somewhat ironically, the idea behind the classification code that distinguishes between biological differences so vigorously is to minimize the influence of biological physics to the lowest level possible and ‘to ensure the success of an athlete is determined by skill, fitness, power, endurance, tactical ability and mental focus’,72 an explanation that reveals the IPCs’ vision of the telos of sport, as vested in the practice of constant exertion and endeavor, rather than in naturally occurring advantages.

Could this approach similarly be applied to the class of abled athletes? What if we were to match the 10 categories of impairment to 10 categories of advantages, where we list all known biological elements that provide a competitive edge, such as LBM, height, vision, muscle strength, oxygen carrying red blood cells, lung size, etc.? We could then assign each athlete a numerical grade in relation to the sport they wish to compete in. Similarly to the IPC classification code, for each sport, the calculation would be different, prioritizing specific traits that benefit athletes in that particular sport. Using a list of advantages rather than looking for a single perfect criterion may help mitigate problems resulting from trying to enforce rules based on non-existing biological dichotomies.

This system would constitute a complete reimagining of our current way of thinking—a plan to ‘start over’. It may be that some sports would remain ‘sexed’ due to consistent differences between males and females within the ‘advantages list’, but other categories would be completely shuffled, producing new winners and losers. After the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, where three athletes in the Paralympics had better times than the gold medalist in the Olympics 1500 m race,73 it is easy to imagine that those traditionally considered disadvantaged would outdo the ‘advantaged’.

CONCLUSION

The controversy over whether or not natural testosterone levels provide a competitive edge is far from over. This note suggests that testosterone should not necessarily be the focal point of attention in designing fairness in sports: human biology is far too complicated to be represented in a single criterion. The socially contested background that brought the testosterone rule to life is likely to continue, and the way it preserves and enforces past ideologies is by creating a concept of fairness that is grounded in differences between males and females rather than other possible categories of biological variation. This note is agnostic to the question of whether or not testosterone levels provide a competitive edge, and leaves it open in order to rethink the concept of fairness in a way that accounts for whatever the answer to this question may be. It ultimately suggests that the construction of fairness is a public practice of rationalization and rule making, which can be reimagined over and over, with winners and losers for any agreed system.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ido Katri, Reut Cohen, and Lihi Yona for very helpful brainstorming on alternative paths to fairness. I would also like to thank Holly Lynch and Quinn Walker for their essential help in revising this note.

Footnotes

Clinical Findings in Hyperandrogenism, The Johns Hopkins Manual of Gynecology and Obstetrics 538 (Johnson Clark et al. eds., 5th ed., 2015).

IAAF, Regulations Governing Eligibility of Females with Hyperandrogenism to Compete in Women's Competition (2011) https://www.iaaf.org/download/download?filename=58438613-aaa7-4bcd-b730-70296abab70c.pdf&urlslug=IAAF%20Regulations%20Governing%20Eligibility%20of%20Females%20with%20Hyperandrogenism%20to%20Compete%20in%20Women%E2%80%99s%20Competition%20-%20In%20force%20as%20from%201st%20May%202011 (accessed Jan. 16, 2017). [hereinafter IAAF Regulation].

Id at13.

Chand v. Athletics Federation of India (AFI) & The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), (2015), https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwi80Mmytt3QAhVP5GMKHQ-uBwMQFggaMAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.tas-cas.org%2Ffileadmin%2Fuser_upload%2Faward_internet.pdf&usg=AFQjCNGqgPIuaQX3ATk9iT0hw0UQL_g27A (accessed Jan. 16, 2017) [hereinafter CAS Arbitration].

For the purpose of this note, I refer to ‘sex’ as the category of biological traits usually attributed to males or females, different from ‘gender’ and ‘gender identity’ the social role attributed by society to individuals, or the sense of self experienced by individuals.

Anne Fausto-Sterling, Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality, 1–4 (2000).

Id. at 3.

Id. at 1–2.

Chad Haldeman-Englert, Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, MedlinePlus (Sept. 11, 2014), https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001180.htm (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

Anne Fausto-Sterling, supra note 6, at 2.

Jeré Longman, Understanding the Controversy Over Caster Semenya, The New York Times (Aug. 18, 2016), http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/20/sports/caster-semenya-800-meters.html (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

IAAF, IAAF to Introduce Eligibility Rules for Females With Hyperandrogenism, IAAF News (Apr. 12, 2012), https://www.iaaf.org/news/iaaf-news/iaaf-to-introduce-eligibility-rules-for-femal-1 (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

Id.

IAAF Regulation, supra note 2, at 1.

Id. at Appendix 2.

Id at 7.

Id. at 9.

Id. at 12.

Athletes that are past the 10 nmol/L threshold but have androgen resistance will be allowed to compete as females on the grounds that they derive ‘no competitive advantage from having androgen levels in the normal male range’, Id.

Juliet Macur, Fighting for the Body She Was Born With, The New York Times (Oct. 6, 2014), https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/07/sports/sprinter-dutee-chand-fights-ban-over-her-testosterone-level.html?_r=0 (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

CAS Arbitration, supra note 4, at 9–10.

LBM represents body weight that is not fat, so athletes with a high LBM are seen as having an athletic advantage. See Id. at 39.

Id. at 141.

Id. at 142.

Id. at 155.

Id. at 158.

International Olympics Committee, IOC Consensus Meeting on Sex Reassignment and Hyperandrogenism 2 (2015), https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/Who-We-Are/Commissions/Medical-and-Scientific-Commission/EN-IOC-Consensus-Meeting-on-Sex-Reassignment-and-Hyperandrogenism.pdf#_ga=1.51499305.1851528621.1481057226 (accessed Jan. 16, 2017) [hereinafter IOC Consensus]; See also IOC Rules Transgender Athletes Can Take Part in Olympics Without Surgery, Guardian (Jan. 24, 2016), https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2016/jan/25/ioc-rules-transgender-athletes-can-take-part-in-olympics-without-surgery (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

IOC Consensus, supra note 27, at 2; Simon Hart, IAAF Offers to Pay for Caster Semenya's Gender Surgery if She Fails Verification Test, Telegraph (Dec. 11, 2009), http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/othersports/athletics/6791558/IAAF-offers-to-pay-for-Caster-Semenyas-gender-surgery-if-she-fails-verification-test.html (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

IOC Consensus, supra note 27, at 2.

Id. at 3.

Id. at 2.

M. L. Healy, et al., Endocrine Profiles in 693 Elite Athletes in the Postcompetition Setting, 81 Clin. Endocrinol. 294 (2014) [hereinafter GH2000 study].

Id. at 298.

When comparing between females with testosterone levels above and under the 8.4 nmol/L threshold, researchers found a variety of differences in many criteria, including fat mass, height, etc. Id. at 295. The study had also established a strong correlation between weight and body mass index, which correlated less strongly with LBM. Id. at 297.

Id. at 298.

Id. at 302.

Relying on a previous study stated to establish the relationship between LBM and athletic performance, a fact also established in CAS Arbitration, supra note 4, at 39.

GH2000 study, supra note 32, at 298.

Id. at 294.

Stéphane Bermon, et al., Serum Androgen Levels in Elite Female Athletes, 99 J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 4328 (2014).

Id. at 4329.

Id. at 4334.

Id. at 4332.

Id. at 4333.

Id. at 4334.

Katrina Karkazis, et al., Out of Bounds? A Critique of the New Policies on Hyperandrogenism in Elite Female Athletes, 12 Am. J. Bioethics 3, 8 (2012) [hereinafter Out of Bounds].

Id. at 13.

Katrina Karkazis & Rebecca Jordan-Young, Debating a ‘Sex Gap’ in Testosterone, 6237 Science 858 (2015).

Id. at 860.

Id. at 859.

Id.

Katrina Karkazis & Rebecca Jordan-Young, The Trouble With Too Much T, The New York Times (Apr. 10, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/11/opinion/the-trouble-with-too-much-t.html (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

The Editors, Naturally Occurring High Testosterone Shouldn’t Keep Female Athletes out of Competition, Scientific American (Aug. 1, 2016), https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/naturally-occurring-high-testosterone-shouldn-t-keep-female-athletes-out-of-competition/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

David Epstein, The Sports Gene Inside the Science Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance (2013).

Alice Domurat Dreger, Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex (1998).

David Epstein & Alice Dreger, Testosterone in Sports, The New York Times (Apr. 16, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/21/opinion/testosterone-in-sports.html (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

David Epstein, How Much Do Sex Differences Matter In Sports?The Washington Post (Feb. 7, 2014), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/how-much-do-sex-differences-matter-in-sports/2014/02/07/563b86a4-8ed9-11e3-b227-12a45d109e03_story.html?utm_term=.19a090644db9 (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

Id.

Laura Geggel, Testosterone Rules for Women Athletes Are Unfair, Researchers Argue, LiveScience (May. 21, 2015, 06:05pm), http://www.livescience.com/50938-female-athletes-testosterone-olympics.html(accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

Roger Pielke Jr, Who Should Be Allowed to Compete As a Female Athlete?, The New York Times (July 29, 2015), http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/29/opinion/who-should-be-allowed-to-compete-as-a-female-athlete.html?_r=1; (accessed Jan. 16, 2017) Arne Ljungqvist & Joe Leigh Simpson, Medical Examination for Health of All Athletes Replacing the Need for Gender Verification in International Sports: The International Amateur Athletic Federation Plan, 267 Jama 850, 851–852 (1992).

Jesse Singal, Should Olympic Athletes Get Sex-Tested at All?, Science of Us (Aug. 18, 2016, 11:04 AM), http://nymag.com/scienceofus/2016/08/should-olympic-athletes-be-sex-tested-at-all.html (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

On disparate media coverage, see Jennifer Dutcher, Where's All the Women's Sports Coverage?Newhouse Syracuse University (June. 30, 2015), https://communications.syr.edu/womens-sports-coverage/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2017). On sex pay gap, see Collin Flake, Mikaela Dufur & Erin Moore, Advantage Men: The Sex Pay Gap in Professional Tennis, 48 Int’l Rev. Soc. Sport 366 (2013); See generally Lea Ann Schell & Stephanie Rodriguez, Our Sporting Sisters: How Male Hegemony Stratifies Women in Sport, 9 Women Sport & Physical Activity J. 15 (2000).

Out of Bounds, supra note 46, at 11.

Id.

The Editors, supra note 53.

Malcolm Gladwell & Nicholas Thompson, Caster Semenya And The Logic Of Olympic Competition, The New Yorker (Aug. 12, 2016), http://www.newyorker.com/news/sporting-scene/caster-semenya-and-the-logic-of-olympic-competition (accessed Jan. 16, 2017). Ross Tucker, The Caster Semenya debate, Science of Sport (July 16, 2016), http://sportsscientists.com/2016/07/caster-semenya-debate/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

Epstein, supra note 54, at 70.

Official website of the Paralympic Movement, https://www.paralympic.org/classification (accessed Dec. 6, 2016).

International Paralympic Committee, Explanatory guide to Paralympic classification 3 (2015), https://www.paralympic.org/sites/default/files/document/150915170806821_2015_09_15%2BExplanatory%2Bguide%2BClassification_summer%2BFINAL%2B.pdf (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).

Id. at 4.

Id. at 30.

Id. at 2.

Maxwell Strachan, Four Paralympians Just Ran The 1500m Faster Than Anyone At The Rio Olympics Final, Huffington Post (Sep. 12, 2016, 01:05 PM), http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/paralympic-1500m-t13_us_57d6d3a8e4b03d2d459b7e78 (accessed Jan. 16, 2017).