Abstract

The Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) Case Registry was established by the American College of Medical Toxicology in 2010. The Registry contains data from participating sites with the agreement that all bedside medical toxicology consultations will be entered. Currently, 83% of accredited medical toxicology fellowship programs in the USA participate. The Registry continues to grow each year, and as of 31 December 2016, a new milestone was reached, with more than 50,000 cases reported since its inception. The objective of this seventh annual report is to summarize the Registry’s 2016 data and activity with its additional 8529 cases. Cases were identified for inclusion in this report by a query of the ToxIC database for any case entered from 1 January to 31 December 2016. Detailed data was collected from these cases and aggregated to provide information which includes the following: demographics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, HIV status), reason for medical toxicology evaluation (intentional pharmaceutical exposure, envenomation, withdrawal from a substance), agent and agent class, clinical signs and symptoms (vital sign abnormalities, organ system dysfunction), treatments and antidotes administered, fatality and life support withdrawal data. Fifty percent of cases involved females, and adults aged 19–65 were the most commonly reported. There were 86 patients (1.0%) with HIV-positive status known. Non-opioid analgesics were the most commonly reported agent class, with acetaminophen the most common agent reported. There were 126 fatalities reported in 2016 (1.5% of cases). Major trends in demographics and exposure characteristics remained similar overall with past years’ reports. While treatment interventions were commonly required, fatalities were rare.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13181-017-0627-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Poisonings, Overdose, Epidemiology, Medical toxicology

Introduction

The Toxicology Investigators Consortium (ToxIC) was created by the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) in 2010 as a tool for clinical toxicology research and toxicosurveillance [1]. Unlike other poisoning databases, ToxIC is a prospective case registry based on medical toxicologists’ experience performing consultations in both inpatient and ambulatory settings. Cases where a formal consultation was not done, such as where advice was given over the telephone, are not included in the database.

The ToxIC Registry is unique in several important ways. Because all information was entered by treating medical toxicologists, the toxicological data reflects the best professional judgment of skilled clinicians. Much of the information on the database is not available from other sources and includes not only medical data but also demographics including race and ethnicity and HIV status.

In 2016, there was a 2.0% decrease in sites included in the ToxIC Registry, with four sites added and five withdrawn or dropped from participation because they withdrew or failed to meet quality standards set by the Registry. Two of the international sites were not included in 2016 due to withdrawal or lack of case entry. At the end of 2016, there were 46 sites, comprising 79 facilities with active case entry. Currently, 83% of active accredited medical toxicology fellowship programs in the USA participate in the ToxIC Registry. The objective of this report is to summarize the Registry’s 2016 data and activity. Cases entered in 2016 are described in this seventh annual report.

Since its inception, several supplemental or subregistries have been created within ToxIC. These are designed to collect more detailed information in specific areas. Our subregistries studying caustic ingestions and prescription opioid abuse were closed at the end of 2016; data from these subregistries are now being analyzed. Subregistries on lipid resuscitation therapy, North American snake bites, and extracorporeal substance removal continued to collect data in 2016 and are continuing into 2017. Three additional subregistries were approved and developed in 2016 and became live on January 1, 2017; these include subregistries on plant, mushroom and herbal toxicity; pediatric opioid exposures; and pediatric marijuana exposures.

In 2016, 14 abstracts and five manuscripts using ToxIC Registry data were published and are listed on http://www.ToxICRegistry.org (Farrugia et al. [2]; Beauchamp et al. [3]; Judge et al. [4]; Riederer et al. [5]; Wang et al. [6]).

In 2016, ToxIC was supported by a continuation of a grant from the US National Institutes of Health on cardiovascular drug toxicity, a new contract with the US Food and Drug Administration, and the continuation of unrestricted grant support from BTG International, which was used to support the North American Snakebite Registry.

Methods

A detailed description of the creation and design of the ToxIC Registry has been previously reported by Wax et al. [1]. To be part of the consortium, all medical toxicologists at participating institutions agree to enter data into the ToxIC Registry on all medical toxicology consultations performed. Cases are entered on a password-protected encrypted online data collection form. The site is maintained by ACMT with oversight by the ToxIC Leadership Group. The Registry is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and does not collect any protected health information or otherwise identifying fields. Registry participation is pursuant to the participating institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and compliant with their policies and procedures. The Registry has also been independently reviewed by the Western IRB and determined not to meet the threshold of human subject research under federal regulation 45 CFR 46 and associated guidance.

Data collected on each case include presenting signs and symptoms, clinical course, treatments, limited patient demographics, outcome, laboratory values, and circumstances of and reasons for toxicological exposure. The term “consultation” is used in this report to describe any in-person encounter with a medical toxicologist in which a formal evaluation was conducted and placed in the medical record. Such encounters may include admission to a medical toxicology in-patient service, or evaluation by a medical toxicologist as a consulting physician in an emergency department, inpatient unit, or outpatient clinic. The online data collection form is formatted to ensure data entry remains organized and searchable. Free text entry fields allow providers to provide further detail or supplementary information. As part of the Registry’s toxicosurveillance mission, one component of the standard data form is a sentinel detection field that signals novel or unusual cases. Analysis of novel exposure surveillance data in the Registry has begun, with results to be published in a separate report.

For this report, a search of the database was performed to identify cases recorded from January 1, 2016, through December 31, 2016. Additional data from the subregistries will be published separately. This descriptive report summarizes case demographics, source and location of consultation, and reasons for encounter, and provides case frequencies by individual agent class and treatment provided.

In the tables describing individual agents or agent classes, unless otherwise indicated, values with fewer than five occurrences were not listed as separate items but are further grouped as “miscellaneous.” Percentages noted in tables for individual agents represent their relative proportion within their respective agent class.

For clinical signs or symptoms, the tables provide the percentage of individual signs or symptoms relative to the total number of Registry cases in 2016. Signs and symptoms include the presence or absence of a toxidrome, vital sign abnormalities, and a variety of organ system-based derangements which may arise from a toxic exposure. For each subheading in the data collection instrument, investigators are required to either select an abnormality, or “None,” to improve the accuracy of data collection. In the detailed treatment tables, percentages for each treatment modality represent the relative frequency among all treatments rendered.

Results

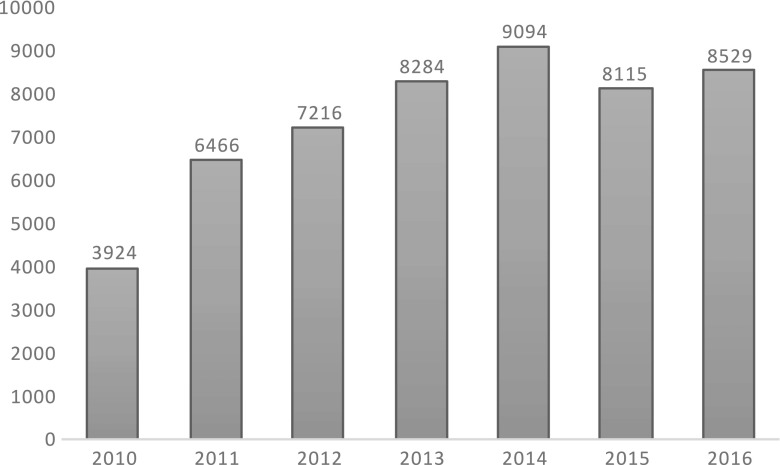

A total of 8529 cases were entered in the ToxIC Registry in 2016, up slightly from 8115 in 2015 (Fig. 1) [2]. Table 1 lists the individual sites entering cases in 2016.

Fig. 1.

Case numbers

Table 1.

Participating institutions providing cases to ToxIC in 2016

| Arizona | |

| Phoenix | |

| Banner- University Medical Center Phoenix | |

| Phoenix Children’s Hospital | |

| California | |

| Fresno | |

| UCSF Fresno Medical Center | |

| Loma Linda | |

| Loma Linda University Medical Center | |

| Los Angeles | |

| University of Southern California Verdugo Hills | |

| San Diego | |

| Rady Children’s Hospital | |

| San Francisco | |

| San Francisco General Hospital | |

| Colorado | |

| Denver | |

| Children’s Hospital Colorado | |

| Denver Health Medical Center | |

| Porter and Littleton Adventist Hospital | |

| Swedish Medical Center | |

| University of Colorado Medical Center | |

| Connecticut | |

| Hartford | |

| Hartford Hospital | |

| Georgia | |

| Atlanta | |

| Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Egelston | |

| Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Hughes Spalding | |

| Emory University Hospital | |

| Emory University Hospital Midtown | |

| Grady Health System | |

| Grady Memorial Hospital | |

| Illinois | |

| Chicago | |

| Cook County Hospital | |

| Evanston | |

| Evanston North Shore University Health System | |

| Indiana | |

| Indianapolis | |

| IU-Eskenazi Hospital | |

| IU-Indiana University Hospital | |

| IU-Methodist Hospital-Indianapolis | |

| IU-Riley Hospital for Children | |

| IU Wishard Memorial Hospital | |

| Massachusetts | |

| Boston | |

| Beth Israel Boston | |

| Children’s Hospital Boston | |

| Worcester | |

| University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center | |

| Michigan | |

| Grand Rapids | |

| Spectrum Health Hospitals | |

| Minnesota | |

| St. Paul | |

| Regions Hospital | |

| Missouri | |

| Kansas City | |

| Children’s Mercy Hospitals & Clinics | |

| St. Louis | |

| Washington University School of Medicine | |

| Nebraska | |

| Omaha | |

| University of Nebraska Medical Center | |

| New Mexico | |

| Albuquerque | |

| University of New Mexico | |

| New Jersey | |

| Morristown | |

| Morristown Medical Center | |

| New Brunswick | |

| Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital | |

| Newark | |

| NJMS/Rutgers | |

| New York | |

| Albany | |

| Albany Medical Center | |

| Manhasset | |

| Long Island Jewish | |

| North Shore University Hospital | |

| New York | |

| Bellevue Medical Center | |

| Mount Sinai Hospital | |

| NYU Langone Medical Center | |

| Staten Island | |

| Staten Island University Hospital | |

| Rochester | |

| Highland Hospital | |

| Strong Memorial Hospital | |

| Syracuse | |

| Upstate Medical University-Downtown Campus | |

| North Carolina | |

| Charlotte | |

| Carolinas Medical Center | |

| Greenville | |

| Vidant Medical Center | |

| Oregon | |

| Portland | |

| Doernbecher Children’s Hospital | |

| Oregon Health & Science University Hospital | |

| Pennsylvania | |

| Harrisburg | |

| PinnacleHealth-Community General Osteopathic | |

| PinnacleHealth-Harrisburg Hospital | |

| PinnacleHealth-West Shore | |

| Lehigh Valley | |

| Lehigh Valley Hospital Cedar Crest | |

| Lehigh Valley Hospital Muhlenberg | |

| Philadelphia | |

| Hahnemann University Hospital | |

| Mercy Fitzgerald Hospital | |

| Mercy Hospital of Philadelphia | |

| St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children | |

| Pittsburgh | |

| UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh | |

| UPMC Magee Women’s Hospital | |

| UPMC Mercy Hospital | |

| UPMC Presbyterian/Shadyside | |

| Texas | |

| Dallas | |

| Children’s Medical Center Dallas | |

| Parkland Memorial Hospital | |

| University of Texas Southwestern Clinic | |

| William P Clements University Hospital | |

| Houston | |

| Ben Taub General Hospital | |

| Texas Children’s Hospital | |

| San Antonio | |

| San Antonio Military Medical Center | |

| Utah | |

| Salt Lake City | |

| Primary Children’s Hospital | |

| University of Utah Hospital | |

| Virginia | |

| Charlottesville | |

| University of Virginia Health Systems | |

| Richmond | |

| Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center | |

| Wisconsin | |

| Milwaukee | |

| Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital | |

| Israel | |

| Haifa | |

| Rambam Health Care Campus |

Demographics

Selected demographics are summarized in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8. In 2016, male (50.0%) and female (50.0%) cases were distributed evenly and 0.6% were pregnant. Adults age 19–65 years comprised the majority (67.0%) of cases, with children age 13–18 years the next most common (16.8%). There were a total of 2280 (26.7%) pediatric cases (0–18 years) overall. The most commonly reported race categories were Caucasian (58.1%) and black/African (14.1%), with 18.0% unknown/uncertain. Nine hundred fifty-one cases (11.2%) reported Hispanic ethnicity, while 19.1% reported ethnicity as unknown. Race and ethnicity are not self-reported in the Registry, and limitations in these data points continue to be addressed with ongoing quality improvement measures.

Table 2.

ToxIC 2016 case demographics—age and gender

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 4267 (50.0) |

| Female | 4262 (50.0) |

| Pregnant | 47 (0.6) |

| Age (years) | |

| <2 | 270 (3.2) |

| 2–6 | 358 (4.2) |

| 7–12 | 215 (2.5) |

| 13–18 | 1437 (16.8) |

| 19–65 | 5714 (67.0) |

| 66–89 | 477 (5.6) |

| >89 | 21 (0.2) |

| Unknown | 29 (0.4) |

| Total | 8529 (100) |

Table 3.

ToxIC 2016 case demographics—race and Hispanic ethnicity

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 4953 (58.1) |

| Unknown/uncertain | 1537 (18.0) |

| Black/African | 1201 (14.1) |

| Other | 466 (5.5) |

| Asian | 169 (2.0) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 76 (0.9) |

| Mixed | 108 (1.3) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 18 (0.2) |

| Australian aboriginal | 1 (0.0) |

| Total | 8529 (100) |

| Hispanic ethnicitya | |

| Hispanic | 951 (11.2) |

| Non-Hispanic | 5949 (69.8) |

| Unknown | 1629 (19.1) |

| Total | 8529 (100) |

aHispanic ethnicity as indicated exclusive of race

Table 4.

ToxIC 2016 case demographics—HIV-positive patients

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Reason for encounter | |

| Intentional pharmaceutical | 42 (49.0) |

| Attempt at self-harm | 27 (31.4) |

| Misuse/abuse | 8 (9.3) |

| Therapeutic use | 3 (3.5) |

| Unknown | 4 (4.7) |

| Intentional non-pharmaceutical | 24 (28.0) |

| Attempt at self-harm | 1 (1.1) |

| Misuse/abuse | 19 (22.1) |

| Unknown | 3 (3.5) |

| Use for therapeutic intent | 1 (1.1) |

| Unintentional pharmaceutical | 1 (1.1) |

| Unintentional non-pharmaceutical | 4 (5.0) |

| Race | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (1.1) |

| Black/African | 29 (33.7) |

| Caucasian | 36 (42.0) |

| Other | 9 (10.5) |

| Unknown/uncertain | 11 (12.8) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 10 (11.6) |

| Not Hispanic | 62 (72.1) |

| Unknown | 14 (16.3) |

| Total HIV-positive patients | 86 (100) |

Table 5.

ToxIC 2016 case referral sources by inpatient/outpatient status

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Emergency department (ED) or inpatient (IP)a | |

| ED | 4772 (59.8) |

| Admitting service | 2085 (26.1) |

| Outside hospital transfer | 729 (9.1) |

| Request from another hospital service (not ED) | 362 (4.5) |

| Poison Center | 27 (0.3) |

| Primary care provider or other outpatient treating physician | 5 (0.1) |

| Self-referral | 5 (0.1) |

| ED/IP total | 7985 (100) |

| Outpatient (OP)/clinic/office consultationb | |

| Primary care provider or other OP physician | 231 (42.5) |

| Self-referral | 211 (38.8) |

| Poison Center | 42 (7.7) |

| Employer/independent medical eval | 39 (7.2) |

| ED | 15 (2.8) |

| Admitting service | 3 (0.6) |

| Request from another hospital service (not ED) | 3 (0.6) |

| OP total | 544 (100) |

aPercentage based on the total number of cases (N = 7985) seen by a medical toxicologist as consultant (ED or IP) or as attending (IP)

bPercentage based on the total number of cases (N = 544) seen by a medical toxicologist as outpatient, clinic visit, or office consultation

Table 6.

ToxIC 2016 cases—primary reason for medical toxicology encounter

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Intentional exposure—pharmaceutical | 4591 (53.8) |

| Intentional exposure—non-pharmaceutical | 1038 (12.2) |

| Unintentional exposure—pharmaceutical | 659 (7.7) |

| Organ system dysfunction | 309 (3.6) |

| Unintentional exposure—non-pharmaceutical | 296 (3.5) |

| Envenomation—snake | 285 (3.3) |

| Unknown | 275 (3.2) |

| Withdrawal—opioid | 264 (3.1) |

| Interpretation of toxicology data | 177 (2.1) |

| Environmental evaluation | 149 (1.7) |

| Withdrawal—ethanol | 140 (1.6) |

| Occupational evaluation | 121 (1.4) |

| Ethanol abuse | 90 (1.1) |

| Envenomation—spider | 43 (0.5) |

| Withdrawal—sedative/hypnotic | 27 (0.3) |

| Malicious/criminal | 22 (0.3) |

| Withdrawal—other | 13 (0.2) |

| Envenomation—other | 10 (0.1) |

| Envenomation—scorpion | 7 (0.1) |

| Marine/fish poisoning | 7 (0.1) |

| Withdrawal—cocaine/amphetamine | 6 (0.1) |

| Total | 8529 (100) |

Table 7.

ToxIC 2016 cases—detailed reason for encounter, intentional pharmaceutical exposures

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Reason for intentional pharmaceutical exposure subgroupa | |

| Attempt at self-harm | 3099 (67.5) |

| Misuse/abuse | 915 (19.9) |

| Therapeutic use | 376 (8.2) |

| Unknown | 202 (4.4) |

| Total | 4592 (100) |

| Attempt at self-harm—suicidal intent subclassificationb | |

| Suicidal intent | 2700 (87.1) |

| No suicidal intent | 115 (3.7) |

| Suicidal intent unknown | 284 (9.2) |

| Total | 3099 (100) |

aPercentage of total number of cases (N = 4592) indicating primary reason for encounter due to intentional pharmaceutical exposure

bPercentage of number of cases (N = 3099) indicating attempt at self-harm

Table 8.

ToxIC 2016 case demographics—race/gender/ethnicity and exposure type

| Intentional pharmaceutical, N (%) | Intentional non-pharmaceutical, N (%) | Unintentional pharmaceutical, N (%) | Unintentional non-pharmaceutical, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 44 (57.9) | 11 (14.5) | 2 (2.6) | 3 (4.0) |

| Asian | 82 (48.5) | 24 (14.2) | 13 (7.7) | 6 (3.6) |

| Black/African | 598 (49.8) | 186 (15.5) | 112 (9.3) | 67 (5.6) |

| Caucasian | 2765 (55.8) | 576 (11.6) | 358 (7.2) | 130 (2.6) |

| Mixed | 53 (49.1) | 14 (13.0) | 9 (8.3) | 7 (6.5) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 13 (72.2) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (5.6) |

| Other | 224 (48.1) | 65 (14.0) | 39 (8.8) | 29 (6.2) |

| Unknown/uncertain | 812 (52.8) | 161 (10.5) | 125 (8.1) | 53 (3.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 485 (51.0) | 119 (12.5) | 71 (7.5) | 60 (6.3) |

| Not Hispanic | 3277 (55.1) | 733 (12.3) | 450 (7.6) | 190 (3.2) |

| Unknown | 829 (50.9) | 186 (11.4) | 138 (8.5) | 46 (2.8) |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 2714 (63.7) | 289 (6.8) | 323 (7.6) | 117 (2.8) |

| Male | 1877 (44.0) | 749 (17.6) | 336 (7.9) | 179 (4.2) |

Table 4 presents demographic data on the 86 HIV-positive patients (1.0%) reported in the Registry. Table 5 details the referral source of medical toxicology evaluations. Table 6 provides information on the type of exposure which prompted a medical toxicology encounter. More detailed information on the intent surrounding the intentional pharmaceutical exposures is provided in Table 7. Table 8 depicts the frequency of common types of exposures as broken down by race, ethnicity, and gender. In all races, and for both Hispanics, non-Hispanics, and both genders, intentional pharmaceutical exposures were more common than intentional non-pharmaceutical exposures.

Agent Classes

There were 11,352 individual agent entries in 2016 for 8529 reported cases with 2519 (29.5%) cases involving multiple agents. The top agent classes were the same as 2015 [2], with non-opioid analgesics the most common (12.8%), followed by sedative-hypnotics/muscle relaxants (11.8%), antidepressants (11.1%), and opioids (9.8%) (Table 9).

Table 9.

ToxIC 2016—agent classes

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Analgesic | 1453 (12.8) |

| Sedative-hypnotic/muscle relaxant | 1339 (11.8) |

| Antidepressant | 1256 (11.1) |

| Opioid | 1118 (9.8) |

| Sympathomimetic | 728 (6.4) |

| Anticholinergic/antihistamine | 704 (6.2) |

| Ethanol | 694 (6.1) |

| Cardiovascular | 654 (5.8) |

| Antipsychotic | 642 (5.7) |

| Anticonvulsant | 370 (3.3) |

| Envenomation and marine | 317 (2.8) |

| Psychoactive | 296 (2.6) |

| Lithium | 176 (1.6) |

| Diabetic medication | 161 (1.4) |

| Cough and cold products | 145 (1.3) |

| Metals | 145 (1.3) |

| Herbal products/dietary supplements | 144 (1.3) |

| Gases/irritants/vapors/dusts | 125 (1.1) |

| Toxic alcohol | 123 (1.1) |

| Hydrocarbon | 94 (0.8) |

| Caustic | 85 (0.7) |

| Household products | 83 (0.7) |

| Plants and fungi | 80 (0.7) |

| Antimicrobial | 73 (0.6) |

| Other pharmaceutical product | 62 (0.5) |

| Other non-pharmaceutical product | 50 (0.4) |

| Anticoagulant | 42 (0.4) |

| Chemotherapeutic/immunological | 42 (0.4) |

| Insecticide | 38 (0.3) |

| Endocrine | 29 (0.3) |

| Gastrointestinal agents | 20 (0.2) |

| Rodenticide | 17 (0.1) |

| Anesthetic | 12 (0.1) |

| Anti-parkinsonism drugs | 9 (0.1) |

| Amphetamine-like hallucinogen | 6 (0.1) |

| Pulmonary | 6 (0.1) |

| Herbicide | 5 (0.0) |

| WMD/riot agent/radiological | 4 (0.0) |

| Ingested foreign body | 3 (0.0) |

| Fungicide | 2 (0.0) |

| Total | 11,352 (100) |

aPercentages are out of total number of reported agent entries per year; 2519 cases (29.5%) reported multiple agents

Individual Agents by Class

Tables 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 26 show frequencies of individual agent entries by class, presented in order of most to least common class. Three agents—ethanol, lithium, and amphetamine-like hallucinogens—are their own classes but are reported with other agent classes (toxic alcohols, anticonvulsants and mood stabilizers, and psychoactives, respectively) for brevity. Tables S1–S18 in the Supplementary Material present frequencies for agent classes with little diversity, few overall cases, or when infrequently reported miscellaneous agents made up a significant portion of entries.

Table 10.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—analgesics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | 987 (67.9) |

| Aspirin | 197 (13.6) |

| Ibuprofen | 164 (11.3) |

| Naproxen | 39 (2.7) |

| Salicylic acid | 26 (1.8) |

| Acetylsalicylic acid | 15 (1.0) |

| Diclofenac | 4 (0.3) |

| Miscellaneousa | 22 (1.5) |

| Class total | 1453 (100) |

aIncludes aminophenazone, unspecified analgesic, carprofen, indomethacin, ketorolac, meloxicam, metamizole (dipyrone), methylsalicylate, unspecified NSAID, phenazopyridine, salicylamide, and salsalate

Table 11.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—sedative-hypnotics/muscle relaxants

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | 704 (52.6) |

| Alprazolam | 276 (20.6) |

| Clonazepam | 207 (15.5) |

| Lorazepam | 99 (7.4) |

| Diazepam | 55 (4.1) |

| Benzodiazepine unspecified | 36 (2.7) |

| Temazepam | 18 (1.3) |

| Miscellaneousa | 13 (1.0) |

| Muscle relaxants | 260 (19.4) |

| Cyclobenzaprine | 92 (6.9) |

| Baclofen | 89 (6.6) |

| Carisoprodol | 37 (2.8) |

| Tizanidine | 20 (1.5) |

| Methocarbamol | 12 (0.9) |

| Metaxalone | 7 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneousb | 3 (0.2) |

| Other sedatives | 230 (17.2) |

| Gabapentin | 157 (11.7) |

| Buspirone | 29 (2.2) |

| Pregabalin | 18 (1.3) |

| Phenibut | 8 (0.6) |

| Etizolam | 7 (0.5) |

| Sedative-hypnotic/muscle relaxant unspecified | 7 (0.5) |

| Miscellaneousc | 4 (0.3) |

| Non-benzodiazepine agonists (“Z” drugs) | 93 (6.9) |

| Zolpidem | 83 (6.2) |

| Eszopiclone | 8 (0.6) |

| Miscellaneousd | 2 (0.1) |

| Barbiturates | 52 (3.9) |

| Butalbital | 24 (1.8) |

| Phenobarbital | 20 (1.5) |

| Miscellaneouse | 8 (0.6) |

| Class total | 1339 (100) |

aIncludes chlordiazepoxide, clorazepate, midazolam, triazolam, flubromazepam, and oxazepam

bIncludes orphenadrine and atracurium

cIncludes propofol and chlomethiazole

dIncludes eszopiclone and zaleplon

eIncludes butabarbital, barbiturate unspecified, and pentobarbital

Table 12.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—antidepressants

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Other antidepressants | 487 (38.8) |

| Bupropion | 260 (20.7) |

| Trazodone | 153 (12.2) |

| Mirtazapine | 57 (4.5) |

| Vilazodone | 5 (0.4) |

| Miscellaneousa | 12 (1.0) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | 431 (34.3) |

| Sertraline | 144 (11.5) |

| Fluoxetine | 100 (8.0) |

| Citalopram | 96 (7.6) |

| Escitalopram | 73 (5.8) |

| Paroxetine | 18 (1.4) |

| Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) | 190 (15.1) |

| Amitriptyline | 125 (10.0) |

| Doxepin | 42 (3.3) |

| Nortriptyline | 18 (1.4) |

| Miscellaneousb | 5 (0.4) |

| Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) | 148 (11.8) |

| Venlafaxine | 90 (7.2) |

| Duloxetine | 49 (3.9) |

| Desvenlafaxine | 5 (0.4) |

| Miscellaneousc | 4 (0.3) |

| Class total | 1256 (100) |

aIncludes antidepressant unspecified, phenelzine, vortioxetine, levomilnacipran, tranylcypromine, and nefazodone

bIncludes clomipramine, imipramine, and desipramine

cIncludes fluvoxamine

Table 13.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—opioids

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Heroin | 316 (28.3) |

| Oxycodone | 199 (17.8) |

| Methadone | 99 (8.9) |

| Opioid unspecified | 90 (8.1) |

| Tramadol | 87 (7.8) |

| Hydrocodone | 86 (7.7) |

| Morphine | 57 (5.1) |

| Buprenorphine | 47 (4.2) |

| Fentanyl | 46 (4.1) |

| Codeine | 36 (3.2) |

| Hydromorphone | 19 (1.7) |

| Loperamide | 9 (0.8) |

| Oxymorphone | 7 (0.6) |

| Naltrexone | 5 (0.4) |

| Miscellaneousa | 15 (1.3) |

| Class total | 1118 (100) |

aIncludes 3-methylfentanyl, desomorphine, naloxone, pentazocine, propoxyphene, remifentanil, tapentadol, and U47700 (designer opioid)

Table 14.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—sympathomimetics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Cocaine | 250 (34.3) |

| Methamphetamine | 187 (25.7) |

| Amphetamine | 90 (12.4) |

| Methylphenidate | 48 (6.6) |

| Dextroamphetamine | 32 (4.4) |

| Methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine | 31 (4.3) |

| Lisdexamfetamine | 24 (3.3) |

| Phenylephrine | 10 (1.4) |

| Pseudoephedrine | 9 (1.2) |

| Phentermine | 8 (1.1) |

| Cathinone | 6 (0.8) |

| Phentermine | 7 (1.2) |

| Sympathomimetic unspecified | 5 (0.7) |

| Miscellaneousa | 28 (3.8) |

| Class total | 728 (100) |

aIncludes 25I-NBOMe, atomoxetine, clenbuterol, dexmethylphenidate, ephedrine, 2C series drugs, epinephrine, 2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromophenethylamine, 4-fluoroamphetamine, 6-(2-Aminopropyl)benzofuran, butylone, N-ethylhexedrone, norepinephrine, phenylethylamine designer drug unspecified, prolintane, and tetrahydrozoline

Table 15.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—anticholinergics and antihistamines

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Diphenhydramine | 416 (59.1) |

| Hydroxyzine | 105 (14.9) |

| Chlorpheniramine | 34 (4.8) |

| Doxylamine | 32 (4.5) |

| Benztropine | 29 (4.1) |

| Promethazine | 16 (2.3) |

| Loratadine | 15 (2.1) |

| Cetirizine | 9 (1.3) |

| Dicyclomine | 6 (0.9) |

| Antihistamine unspecified | 5 (0.7) |

| Cyproheptadine | 5 (0.7) |

| Miscellaneousa | 32 (4.5) |

| Class total | 704 (100) |

aIncludes anticholinergic unspecified, atropine, belladonna, brompheniramine, cyclopentolate, dimenhydrinate, fexofenadine, glycopyrrolate, hyoscyamine, meclizine, oxybutynin, pyrilamine, scopolamine, trihexyphenidyl, and triprolidine

Table 16.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries— ethanol and toxic alcohols

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Ethanola | 694 (100) |

| Non-ethanol alcohols and glycols | |

| Ethylene glycol | 56 (45.5) |

| Isopropanol | 40 (32.5) |

| Methanol | 17 (13.8) |

| Propylene glycol | 4 (3.3) |

| Miscellaneousb | 6 (4.9) |

| Class total | 123 (100) |

aEthanol is considered a separate agent class

bIncludes acetone, denatured alcohol non-ethanol, diethylene glycol, glycol ethers, and toxic alcohol unspecified

Table 17.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—cardiovascular

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Beta blockers | 181 (27.7) |

| Metoprolol | 70 (10.7) |

| Propranolol | 56 (8.6) |

| Atenolol | 24 (3.7) |

| Carvedilol | 16 (2.4) |

| Labetalol | 7 (1.1) |

| Miscellaneousa | 8 (1.2) |

| Sympatholytics | 169 (25.8) |

| Clonidine | 141 (21.6) |

| Guanfacine | 28 (4.3) |

| Calcium channel antagonists | 113 (17.3) |

| Amlodipine | 63 (9.6) |

| Diltiazem | 23 (3.5) |

| Verapamil | 18 (2.8) |

| Nifedipine | 8 (1.2) |

| Miscellaneousb | <5 (<0.8) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors | 52 (8.0) |

| Lisinopril | 47 (7.2) |

| Miscellaneousc | 5 (0.8) |

| Cardiac glycosides | 46 (7.0) |

| Digoxin | 44 (6.7) |

| Digitoxin | 2 (0.3) |

| Other antihypertensives and vasodilators | 32 (4.9) |

| Prazosin | 16 (2.4) |

| Miscellaneousd | 16 (2.4) |

| Antidysrhythmics and other cardiovascular agents | 27 (4.1) |

| Atorvastatin | 8 (1.2) |

| Simvastatin | 6 (1.0) |

| Miscellaneouse | 13 (2.0) |

| Diuretics | 25 (3.8) |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 16 2.4) |

| Furosemide | 5 (0.8) |

| Miscellaneousf | 4 (0.6) |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 9 (1.4) |

| Losartan | 5 (0.8) |

| Miscellaneousg | 4 (0.6) |

| Class total | 654 (100) |

aIncludes nebivolol, bisoprolol, nadolol, and timolol

bIncludes nicardipine

cIncludes benazepril, enalapril, and quinapril

dIncludes hydralazine, nitroprusside, isosorbide, nitroglycerin, terazosin, alkyl nitrite, doxazosin, and minoxidil

eIncludes flecainide, sotalol, amiodarone, midodrine, cardiovascular agent unspecified, quinidine, pravastatin

fIncludes chlorthalidone, acetazolamide, spironolactone

gIncludes valsartan, irbesartan, olmesartan

Table 18.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—antipsychotics

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Quetiapine | 307 (47.8) |

| Olanzapine | 87 (13.6) |

| Aripiprazole | 52 (8.1) |

| Risperidone | 41 (6.4) |

| Haloperidol | 39 (6.1) |

| Clozapine | 26 (4.0) |

| Lurasidone | 20 (3.1) |

| Ziprasidone | 17 (2.6) |

| Chlorpromazine | 15 (2.3) |

| Paliperidone | 9 (1.4) |

| Perphenazine | 7 (1.1) |

| Fluphenazine | 6 (0.9) |

| Miscellaneousa | 16 (2.5) |

| Class total | 642 (100) |

aIncludes antipsychotic unspecified, asenapine, brexpiprazole, loxapine, penfluridol, prochlorperazine, thiothixene, and trifluoperazine

Table 19.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—anticonvulsants and mood stabilizers, and lithium

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Lithiuma | 176 (100) |

| Lamotrigine | 100 (27.0) |

| Valproic acid | 98 (26.5) |

| Phenytoin | 56 (15.1) |

| Carbamazepine | 42 (11.4) |

| Topiramate | 29 (7.8) |

| Oxcarbazepine | 20 (5.4) |

| Levetiracetam | 9 (2.4) |

| Miscellaneousb | 16 (4.3) |

| Class total | 370 (100) |

aLithium is considered a separate agent class

bIncludes anticonvulsant unspecified, divalproex, fosphenytoin, lacosamide, and zonisamide

Table 20.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—envenomations and marine poisonings

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Crotalus spp. | 106 (34.1) |

| Agkistrodon spp. | 96 (30.9) |

| Snake unspecified | 64 (20.6) |

| Loxosceles spp. | 13 (4.2) |

| Latrodectus spp. | 10 (3.2) |

| Centuroides spp. | 5 (1.6) |

| Hymenoptera | 5 (1.6) |

| Spider unspecified | 5 (1.6) |

| Miscellaneousa | 7 (2.3) |

| Class total | 311 (100) |

aIncludes Naja nigricinta, Vipera palaestinae, Micrurus spp., scorpion unspecified, and stingray

Table 21.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—psychoactives

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Cannabinoid synthetic | 95 (31.5) |

| Marijuana | 88 (29.1) |

| LSD | 22 (7.3) |

| Phencyclidine | 20 (6.6) |

| Gamma hydroxybutyrate | 16 (5.3) |

| Cannabinoid non-synthetica | 12 (4.0) |

| Ketamine | 11 (3.6) |

| Nicotine | 9 (3.0) |

| Molly-amphetamine-like hallucinogenb | 6 (2.0) |

| Miscellaneousc | 23 (7.6) |

| Class total | 302 (100) |

aThe cannabinoid nonsynthetic group refers to exposures to unspecified naturally occurring cannabinoids, such as cannabis extracts or cannabidiol

bAmphetamine-like hallucinogens are presented with psychoactives for brevity, though listed as an individual Registry class

cIncludes 1-propionyl-lysergic acid diethylamide (1P-LSD), 3-methoxyphencyclidine, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), donepezil, gamma butyrolactone, hallucinogen unspecified, hallucinogenic amphetamines, methylenedioxymethamphetamine, methylone, pharmaceutical tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), psychoactive unspecified, and varencicline

Table 22.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—diabetic medications

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Metformin | 66 (41.0) |

| Insulin | 40 (24.8) |

| Glipizide | 26 (16.1) |

| Glyburide | 14 (8.7) |

| Glimepiride | 8 (5.0) |

| Miscellaneousa | 7 (4.3) |

| Class total | 161 (100) |

aIncludes empagliflozin, exenatide, gliclazide, and saxagliptin

Table 23.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—metals

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Lead | 44 (30.3) |

| Iron | 30 (20.7) |

| Mercury | 20 (13.8) |

| Chromium | 11 (7.6) |

| Cobalt | 7 (4.8) |

| Arsenic | 5 (3.4) |

| Copper | 5 (3.4) |

| Miscellaneousa | 23 (15.9) |

| Class total | 145 (100) |

aIncludes manganese, metal unspecified, cadmium, silver, titanium, antimony, barium, magnesium, nickel, selenium, thorium, uranium, and zinc sulfate

Table 24.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—gases, irritants, vapors, and dusts

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Carbon monoxide | 54 (43.2) |

| Hydrogen sulfide | 14 (11.2) |

| Cyanide | 11 (8.8) |

| Smoke | 10 (8.0) |

| Chlorine | 5 (4.0) |

| Gas/irritant/vapor/dust unspecified | 5 (4.0) |

| Miscellaneousa | 26 (20.8) |

| Class total | 125 (100) |

aIncludes petroleum vapors, silica, chloramine, diesel exhaust, dust, ethylene oxide, sewer gas, acetonitrile, duster (canned air), ethylene, natural gas, nitric oxide, ozone, plastic fumes, polyurethane vapors, welding fumes, and vaping NOS

Table 25.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—household products

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sodium hypochlorite ≤6% | 26 (31.3) |

| Cleaning solutions and disinfectants | 17 (20.5) |

| Laundry detergent pod | 11 (13.3) |

| Ammonia ≤10% | 6 (7.2) |

| Paint | 5 (6.0) |

| Miscellaneousa | 18 (21.7) |

| Class total | 83 (100) |

aIncludes deodorants and antiperspirants, dishwasher detergent, dishwasher detergent pod, flower food, hair product, hand sanitizer unspecified, household product unspecified, mouthwash unspecified, perfume, phenylenediamine (hair dye), soaps and detergents, sunscreens, and windshield washer fluid

Table 26.

ToxIC 2016 agent entries—plants and fungi

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Mold unspecified | 33 (41.3) |

| Mushroom, other/unknown | 9 (11.3) |

| Mitragyna speciosa (kratom) | 6 (7.5) |

| Mushroom, psilocibin | 4 (5.0) |

| Valerian root | 4 (5.0) |

| Miscellaneousa | 24 (30.0) |

| Class total | 80 (100) |

aIncludes aconitum, Agastache scrophulariifolia (purple giant hyssop), Amanita muscaria, Brugmansia (angels trumpet), Convallaria majalis (lily of the valley), Crataegus (hawthorn), Datura inoxia (moonflower, thornapple), Dieffenbachia, Ganoderma mushroom, kola nut, kombucha tea, Nerium oleander, petasites (butterbur), Phytolacca americana (pokeweed), Piper methysticum (kava), plants and fungi unspecified, poppy seeds (Papaver), Ricinus communis (castor beans), and Sanseviera (Snake plant, Mother in Laws tongue)

Table 10 presents the non-opioid analgesics class. This has been the most frequently reported agent class since 2013 [2, 7, 8]. The most common agent was acetaminophen (67.9%), which was also the most common agent in the Registry overall, involved in 11.6% cases, consistent with previous years.

Table 11 reports the sedative-hypnotics/muscle relaxants class. Benzodiazepines were the most frequently reported (52.6%) with alprazolam (20.6%), clonazepam (15.5%), and lorazepam (7.4%) the top three reported. In 2016, alprazolam eclipsed clonazepam as the most commonly reported benzodiazepine for the first time since the ToxIC Registry began [2, 7–11]. Other commonly reported agents in this class included the muscle relaxants cyclobenzaprine and baclofen, gabapentin (in the “Other sedatives” subclass), and zolpidem (in the “Non-benzodiazepine agonists” subclass). Barbiturates were infrequently mentioned, consistent with prior years.

Table 12 presents the antidepressant class. Bupropion (in the “Other antidepressants” subclass) was the most frequently reported, comprising 20.7% of antidepressant cases and 3.0% of 2016 Registry cases overall, consistent with prior years. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), particularly sertraline and fluoxetine, were the second most common subclass (34.3%), followed by the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (15.1%) (e.g., amitriptyline), and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (e.g., venlafaxine).

Table 13 summarizes opioid frequencies, including naturally derived, synthetic, and semisynthetic agents. As in previous years, heroin was the most commonly reported (28.3%), followed by oxycodone (17.8%) and methadone (8.9%).

Table 14 reports the sympathomimetic class. Cocaine was the most commonly reported (34.3%), followed by methamphetamine (25.7%) and amphetamine (12.4%), consistent with previous years. The pharmaceutical stimulants methylphenidate and lisdexamfetamine together accounted for 9.9% of the class. A number of designer stimulant drugs were reported, with methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine the most common (4.3%). Less common designer agents, combined in the miscellaneous category, included the 2C series drugs, 25I-NBOMe, and other unspecified phenethylamines.

Table 15 describes the anticholinergic and antihistamine class (Table 15), and the most commonly reported agent was diphenhydramine (59.1%), which was also one of the most commonly reported agents in the Registry overall, involved in 4.9% of cases. Hydroxyzine was the next most common (14.9%), followed by other first-generation antihistamines chlorpheniramine and doxylamine. Second-generation antihistamines were reported less frequently.

Table 16 presents frequencies for ethanol and the toxic alcohols. Ethanol was again the second most commonly reported agent overall in the Registry (N = 694), involved in 8.1% of cases. Among the toxic alcohols, ethylene glycol was the most common (45.5%), followed by isopropanol (32.5%), while methanol was less commonly reported (13.8%).

Table 17 presents the cardiovascular agent class. The 654 cardiovascular agent entries comprised 5.8% of all Registry entries in 2016. In this class, beta adrenergic receptor antagonists (beta-blockers) were the most commonly reported (27.7%), followed by sympatholytics (25.8%), similar to prior years. Metoprolol was the most common beta-blocker. Clonidine (21.6%) was the most common sympatholytic reported with guanfacine also reported but to a much lower extent (4.3%). Together, the calcium channel antagonists comprised 17.3% of the agent class, with amlodipine the most common, followed by diltiazem and verapamil. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors comprised only 8.0% of the cardiovascular agent mentions, with lisinopril accounting for >90% of these. Forty-six cardiac glycoside cases were reported, with all involving digoxin except for two digitoxin cases. Other subgroups of cardiovascular agents were less commonly reported.

Table 18 summarizes the 642 antipsychotic agents reported, which accounted for 5.7% of all Registry entries in 2016. Consistent with prior years, quetiapine was by far the most commonly encountered antipsychotic agent. There were more than three times as many quetiapine cases reported (47.8%) as olanzapine (13.6%), the next most common agent. On its own, quetiapine was listed in 3.6% of all Registry cases in 2016. Aripiprazole was also frequently reported (8.1%), similar to past years. Risperidone, haloperidol, and clozapine together accounted for an additional 16.5% of the antipsychotic agent class.

Table 19 shows anticonvulsants and mood stabilizers. Lithium is considered a unique agent class and reported separately in Table 19. Lithium was reported in 176 cases, representing 2.1% of total Registry cases in 2016. Lamotrigine and valproic acid were the two most commonly reported agents in the anticonvulsants and mood stabilizers class. These were followed by phenytoin, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate.

Table 20 presents information on envenomations and marine poisonings. This class was dominated by snake envenomations in 2016, consistent with prior years. Crotalus spp. were the most commonly reported (34.1%), followed by Agkistrodon spp. (30.9%), and unspecified snakes (20.6%). Spider envenomations (e.g., Loxosceles spp., Latrodectus spp., and unspecified spider) were less common, together making up 9.0% of the class.

Table 21 summarizes the psychoactive agent class, which includes marijuana and other cannabinoid receptor agonists, hallucinogens, and dissociatives. Synthetic cannabinoids were the most frequently entered (32.1%), followed by marijuana, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), phencyclidine, and gamma hydroxybutyrate. Amphetamine-like hallucinogens are reported with the psychoactives in Table 21.

Table 22 reports data on diabetic medications. Agent frequencies were similar to previous years, with metformin (41.0%) and insulin (24.8%) the most common. These were followed by the sulfonylurea agents: glipizide, glyburide, and glimepiride.

Table 23 presents the metals agent class which was dominated by lead (30.3%), iron (20.7%), and mercury (13.8%), followed by chromium (7.6%) and cobalt (4.8%). The miscellaneous subclass, comprised of 13 different agents, accounted for 15.9% of entries.

Table 24 presents the gases, irritants, vapors, and dusts class. Carbon monoxide was the predominant agent (43.2%), followed hydrogen sulfide (11.2%), and cyanide and smoke (16.8% combined).

Table 25 reports household product exposures. Sodium hypochlorite ≤6% (household bleach) was the most common (31.3%), followed by other cleaning solutions and disinfectants (20.5%) and laundry detergent pods (13.3%). Caustic agents are described separately in Table S4 in the Supplemental Material.

Table 26 presents the diverse species of the plants and fungi agent class. Consistent with prior years, unspecified mold and unknown mushrooms were the predominant agents, followed by Mitragyna speciosa (kratom), and a miscellaneous category containing 19 different plant and fungi agents.

Additional agent classes presented in the Supplementary Material include cough and cold products (Table S1), herbal products and dietary supplements (Table S2), hydrocarbons (Table S3), caustics (Table S4); antimicrobials (Table S5), other pharmaceutical products (Table S6), other non-pharmaceutical products (Table S7), anticoagulants (Table S8), chemotherapeutic/immunological agents (Table S9), pesticides, including herbicides, insecticides, rodenticides, and fungicides (Table S10), endocrine agents (Table S11), gastrointestinal agents (Table S12), anesthetics (Table S13), anti-parkinsonism drugs (Table S14), pulmonary agents (Table S15), weapons of mass destruction/riot/radiological agents (Table S16), and ingested foreign bodies (Table S17).

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Table 27 summarizes the 3134 clinical toxidromes reported in 2016. The frequencies of reported toxidromes were similar to past years with sedative-hypnotic the most common (14.9%), followed by anticholinergic (7.4%), sympathomimetic (4.5%), and opioid (4.4%).

Table 27.

ToxIC 2016 cases—toxidromes

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Sedative-hypnotic | 1261 (14.9) |

| Anticholinergic | 629 (7.4) |

| Sympathomimetic | 386 (4.5) |

| Opioid | 378 (4.4) |

| Serotonin syndrome | 259 (3.0) |

| Alcoholic ketoacidosis | 87 (1.0) |

| Sympatholytic | 50 (0.6) |

| Washout syndrome | 36 (0.4) |

| NMS | 19 (0.2) |

| Cholinergic | 16 (0.2) |

| Overlap syndromes (MCS, chronic fatigue, etc.) | 10 (0.1) |

| Miscellaneousb | 8 (0.1) |

| Total | 3134 (36.7) |

NMS neuroleptic malignant syndrome

aPercentage equals number cases reporting specific toxidrome relative to total number of Registry cases in 2016 (N = 8529)

bIncludes anticonvulsant hypersensitivity and fume fever

Table 28 summarizes the 2627 major vital sign abnormalities recorded in 2016. Tachycardia was the most common (12.1%), followed by hypotension (8.0%), bradycardia (4.6%), and several others affecting <4% of total cases. Note that some cases reported more than one major vital sign abnormality. Additionally, cases may include more than one of the other signs/symptom categories described below.

Table 28.

ToxIC 2016 cases—major vital sign abnormalities

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Tachycardia (HR >140) | 1031 (12.1) |

| Hypotension (systolic BP < 80 mmHg) | 684 (8.0) |

| Bradycardia (HR < 50) | 393 (4.6) |

| Bradypnea (RR < 10) | 249 (2.9) |

| Hypertension (systolic BP > 200 mmHg and/or diastolic BP > 120 mmHg) | 224 (2.6) |

| Hyperthermia (temperature > 105 °F) | 46 (0.5) |

| Total | 2627 (30.8)b |

HR heart rate, BP blood pressure, RR respiratory rate

aPercentage equals the number of cases relative to the total number of Registry cases in 2016 (N = 8259)

bTotal reflects cases reporting at least one major vital sign abnormality; cases may be associated with more than one major vital sign abnormality

Table 29 summarizes the neurological signs and symptoms reported in 2016. While the overall numbers of cases with neurological signs and symptoms increased from previous years, the order remained similar, with coma/central nervous system depression the most common (34.7%), followed by agitation (16.7%) and delirium (11.8%).

Table 29.

ToxIC 2016 cases—neurological signs and symptoms

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Coma/CNS depression | 2959 (34.7) |

| Agitation | 1421 (16.7) |

| Delirium | 1005 (11.8) |

| Hyperreflexia/myoclonus/tremor | 635 (7.4) |

| Seizures | 459 (5.4) |

| Hallucinations | 366 (4.3) |

| Weakness/paralysis | 142 (1.7) |

| Dystonia/rigidity/extrapyramidal symptoms | 112 (1.3) |

| Numbness/Paresthesia | 79 (0.9) |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 25 (0.3) |

| Total | 4970 (58.3)a,b |

CNS central nervous system

aPercentage equals number of cases relative to total number of Registry cases in 2016 (N = 8529)

bTotal reflects cases reporting at least one neurological symptom; cases may be associated with more than one neurological symptom

Table 30 summarizes the cardiovascular and pulmonary signs and symptoms reported in 2016. Although the total number of cardiovascular and pulmonary signs reported was higher this year than in previous years, the order remained similar, with prolonged QTc (≥500ms) the most common cardiovascular sign (5.6%), followed by prolonged QRS (≥120 ms) (1.8%). The most common pulmonary sign was respiratory depression (11.1%).

Table 30.

ToxIC 2016 cases—cardiovascular and pulmonary signs

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | |

| Prolonged QTc (≥500 ms) | 480 (5.6) |

| Prolonged QRS (≥120 ms) | 150 (1.8) |

| Ventricular dysrhythmia | 102 (1.2) |

| Myocardial injury or infarction | 61 (0.7) |

| AV block (>1st degree) | 41 (0.5) |

| Total | 834 (9.8)b |

| Pulmonary | |

| Respiratory depression | 946 (11.1) |

| Aspiration pneumonitis | 182 (2.1) |

| Acute lung injury/ARDS | 117 (1.4) |

| Asthma/reactive airway disease | 60 (0.7) |

| Total | 1305 (15.3)b |

ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome

aPercentage equals number cases reporting signs of symptoms relative to total number of Registry cases in 2016 (N = 8529)

bTotal reflects cases reporting at least one cardiovascular or pulmonary symptom; cases may be associated with more than one symptom

Table 31 summarizes signs and symptoms involving other organ systems. As in the past years, metabolic signs (e.g., elevated anion gap, metabolic acidosis) were common, reported in 12.2% of cases. Renal and musculoskeletal signs (e.g., rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury) were also common (10.3%), followed by hematological (6.2%), gastrointestinal/hepatic (5.3%), and dermal (3.4%) signs and symptoms.

Table 31.

ToxIC 2016 cases—clinical signs—other organ systems

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Metabolic | |

| Elevated anion gap (>20) | 459 (5.4) |

| Metabolic acidosis (pH <7.2) | 387 (4.5) |

| Hypoglycemia (glucose <50 mg/dL) | 126 (1.5) |

| Elevated osmole gap (>20) | 61 (0.7) |

| Total | 1033 (12.1)b |

| Gastrointestinal/hepatic | |

| Hepatotoxicity (AST ≥1000 IU/L) | 296 (3.5) |

| Pancreatitis | 64 (0.8) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 49 (0.6) |

| Corrosive injury | 42 (0.5) |

| Intestinal ischemia | 5 (0.1) |

| Total | 456 (5.3)b |

| Hematological | |

| Coagulopathy (PT >15 s) | 199 (2.3) |

| Leukocytosis (WBC >20 K/μL) | 131 (1.5) |

| Thrombocytopenia (platelets <100 K/μL) | 102 (1.2) |

| Hemolysis (Hgb <10 g/dL) | 56 (0.7) |

| Pancytopenia | 21 (0.2) |

| Methemoglobinemia (MetHgb ≥2%) | 18 (0.2) |

| Total | 527 (6.2)b |

| Renal/musculoskeletal | |

| Rhabdomyolysis (CPK >1000 IU/L) | 489 (5.7) |

| Acute kidney injury (creatinine >2.0 mg/dL) | 386 (4.5) |

| Total | 875 (10.3)b |

| Dermatological | |

| Rash | 165 (1.9) |

| Blister/bullae | 71 (0.8) |

| Necrosis | 31 (0.4) |

| Angioedema | 25 (0.3) |

| Total | 292 (3.4)b |

AST aspartate aminotransferase, PT prothrombin time, WBC white blood cells, Hgb hemoglobin, CPK creatine phosphokinase

aPercentage equals the number of cases reporting specific clinical signs compared to the total number of Registry cases in 2016 (N = 8529)

bTotal reflects cases reporting at least one sign in the category; cases may be associated with more than one symptom

Fatalities

Tables 32 and 33 present data on ToxIC 2016 cases involving exposures which resulted in fatalities, with Table 32 including cases involving single agent exposures and Table 33 including cases involving multiple agents. Table S18 in the Supplementary Information summarizes information on fatality cases with no suspected toxicologic exposure, or an unknown exposure(s).

Table 32.

ToxIC 2016 fatality cases with known toxicological exposure, single agent

| Age/sexa | Agents involved | Clinical findings | Life support withdrawn | Brain death confirmed | Treatmentb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40M | Acetaminophen | HT, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, PNC, CPT, PLT, AKI, RBM | No | Unknown | NAC, vitamin K, vasopressors, anticonvulsants, neuromuscular blockers, opioids, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 41F | Acetaminophen | TC, RD, AGT, CNS, AG, HPT, PNC, HYS, AKI, RBM | Yes | Unknown | NAC, vitamin K, benzodiazepines, intubation, IV fluids |

| 21F | Heroin | HT, BC, BP, VD, RD, CNS, MA | Yes | Yes | Physostigmine, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 41F | Acetaminophen | HT, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, CPT, WBC, RBM | Yes | No | NAC, NaHCO3, vitamin K, vasopressors, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, opioids, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 43M | Methanol | HT, QRS, RD, CNS, MA, AG, OG, CPT, AKI, RBM | Yes | Yes | Folate, fomepizole, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluids |

| 29F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, CNS, HGY, HPT, CPT, AKI | Yes | No | NAC, NaHCO3, vitamin K, benzodiazepines, glucose, neuromuscular blockers, opioids, vasodilators, hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 52M | Ethanol | HT, TC, MA, AG, HPT, PNC, PLT, AKI | Unknown | Unknown | NAC, vasopressors, continuous renal replacement, cardioversion, intubation, IV fluids |

| 35F | Amitriptyline | HT, TC, BP, VD, QRS, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, AKI | Yes | Yes | Naloxone, NaHCO3, vasopressors, CPR, intubation, IV fluids |

| 54M | Ethanol | CNS | Yes | Yes | Fomepizole, NAC, hemodialysis, intubation, transfusion |

| 80M | Carbon monoxide | HT, AVB, RD, CNS, WKN, MA, OTH1 | Yes | No | Hydroxocobalamin, vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 77M | Metoprolol | HT, BC, AVB, RD, CNS | Yes | No | Insulin-euglycemic therapy, vasopressors, glucose, intubation, IV fluids |

| 51F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, BC, BP, VD, ALI, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, HYS, CPT, PLT, WBC, AKI | Yes | No | Lipid resuscitation, methylene blue, NAC, NaHCO3, vasopressors, intubation, transfusion |

| 51F | Heroin | HT, BP, RD, CNS, HPT, WBC, RBM | Yes | Yes | NaHCO3, vasopressors, benzodiazepines, intubation, IV fluids |

| 24F | Acetaminophen | HT, VD, CNS, HGY, MA, AG, HPT, PNC, PLT | Yes | No | NAC, vasopressors, benzodiazepines, glucose, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 63F | Acetaminophen | HT, BC, BP, VD, ALI, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, PNC, INT, CPT, PLT, WBC | No | No | NAC, vasopressors, CPR, intubation, IV fluids |

| 60M | Colchicine | HT, VD, MA, AG, CPT, PLT, PCT, WBC | No | No | Vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 51M | Metformin | HT, TC, ALI, MA, AG, RBM | Unknown | Unknown | Hemodialysis, intubation |

| 83F | Diltiazem | HT, BC, CNS, MA, AG, | Unknown | Unknown | Glucagon, insulin-euglycemic therapy, lipid resuscitation, vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 40F | Heroin | BP, CNS, MA | Yes | Yes | NAC, naloxone, |

| 57M | Bupropion | VD, AP, ALI, CNS, SZ, AKI | No | No | Lipid resuscitation, NaHCO3, vasopressors, benzodiazepines, CPR, intubation, IV fluids |

| 19M | Fentanyl | RD, CNS | Yes | Yes | Naloxone, CPR, intubation |

| 14F | Diphenhydramine | HT, VD, QTc, QRS, CNS, SZ, MA, AG | Yes | No | Vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, intubation, IV fluids |

| 63F | Doxepin | RD, CNS, AKI | Yes | No | Glucagon, NaHCO3, intubation, IV fluids |

| 22F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, RD, CNS, SZ, MA, AG, HPT, CPT | Yes | Yes | NAC, vasopressors, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, intubation, IV fluids, |

| 14F | Bupropion | HT, QRS, ALI, RD, CNS, SZ, MA, AKI, RBM | Yes | Unknown | Insulin-euglycemic therapy, lipid resuscitation, NaHCO3, vasopressors, urinary alkalinization, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 60F | Quinidine | MET | No | No | Calcium, methylene blue, NaHCO3, vitamin K, vasopressors, hypoglycemia, exchange transfusion, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 52M | Sevoflurane | HTN, TC, HYT, VD, QTc, QRS, EPS | Yes | No | Dantrolene, NaHCO3, intubation, IV fluids |

| 32M | Cyanide | HT, TC, CNS, MA | No | No | Hydroxocobalamin, intubation, IV fluids |

| 19F | Acetaminophen | None listed | No | No | NAC, IV fluids |

| 47M | Hydromorphone | AP | No | No | NAC, IV fluids |

| 65F | Digoxin | HT, BC, WKN | Yes | No | Digoxin Fab, vasopressors, IV fluids |

| 60F | Amitriptyline | HT, TC, VD, QRS, RAD, ALI, RD, | Yes | No | NaHCO3, vasopressors, intubation, intubation, IV fluids |

| 17F | Cocaine | TC, RD, AGT, CNS, DLM, SZ, MA, AG, HPT, HYS, CPT, PLT, WBC, AKI | Yes | No | Vasopressors, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, glucose, opioids, hemodialysis, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 32M | Cyanide | HT, VD, RAD, AGT, CNS, MA | No | No | Hydroxocobalamin, thiosulfate, vasopressors, CPR, intubation, IV fluids |

| 51M | Warfarin | CNS, CPT, WBC | Yes | Yes | Anticoagulant reversal, anticonvulsants, neuromuscular blockers, intubation |

| 33M | Hydrogen sulfide | HT, TC, VD, ALI, RD, CNS, MA | Yes | Unknown | Vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, benzodiazepines, CPR, cardioversion, intubation, IV fluids |

| 61M | Ethanol | HT, DLM, HCN, HPT, PNC, HYS, PLT | Yes | Unknown | Calcium, folate, octreotide, thiamine, benzodiazepines, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 21F | Acetaminophen | HT, BC, VD, ALI, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, CPT, AKI | No | No | NAC, NaHCO3, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, benzodiazepines, CPR, cardioversion, intubation, IV fluids |

| 45M | Codeine | HT, BC, VD, RD, CNS, MA, AG, | Yes | Yes | NAC, NaHCO3, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, anticonvulsants, beta blockers, opioids, CPR, cardioversion, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| >89M | Carbon monoxide | HT, VD, RD, CNS, AG | No | No | Thiosulfate, vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 68M | Digoxin | HT, QRS, RD, AGT, CNS | Yes | Unknown | Digoxin Fab, pacemaker |

| 39F | Gabapentin | HT, VD, QTc, MI, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, MI, WBC, AKI, RBM | Yes | No | Vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, CPR, intubation, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 38F | Acetaminophen | HT, TC, MI, ALI, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, GIB, HYS, CPT, PLT, PCT, AKI, RBM | Yes | Unknown | NAC, NaHCO3, vitamin K, vasopressors, glucose, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 68M | Chlorine | HT, QTc, MI, ALI, RD, CNS | No | No | Vasopressors, neuromuscular blockers, intubation, IV fluids |

| 68M | Copper | HT, CRV, GIB, MET, WBC, AKI | No | No | BAL, penicillamine, vasopressors, hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 46M | Amlodipine | HT, RAD, CNS, MA, AKI | Yes | No | Lipid resuscitation, methylene blue, NaHCO3, thiamine, vitamin K, vasopressors, bronchodilators, antiarrhythmics, benzodiazepines, neuromuscular blockers, opioids, steroids, intubation, IV fluids |

| 24M | Opioid unspecified | VD, QTc, QRS, MI, AP, RD, CNS, MA, | Yes | Yes | None listed |

| 74M | Ciguatera | PST, WKN | Yes | No | None listed |

| 27M | Morphine | HT, BP, MI, RAD, ALI, RD, CNS, MA, AG. CPT, AKI, RBM | Yes | Yes | Naloxone, vasopressors, CPR, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 38M | Heroin | HT, TC, MI, ALI, CNS, NP, MA, WBC | Unknown | Unknown | Folate, naloxone, vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 31M | Heroin | HT, VD, QRS, MI, RAD, RD, CNS, MA, AG, AKI | Yes | Yes | None listed |

| 58M | Amphetamine | QRS, QTc, AGT, MA, AG, OG, INT, PLT, AKI | Yes | Unknown | Fomepizole, vasopressors, hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement, intubation |

| 44F | Heroin | HT, BP, VD, RD, CNS, MA, AG, | No | No | Naloxone, vasopressors, CPR, intubation, IV fluids |

| 34M | Heroin | RD, CNS | Unknown | Unknown | Naloxone, CPR |

| 26M | Heroin | CNS | Yes | Yes | Naloxone, intubation |

| 70M | Diltiazem | HT, CNS | Yes | Yes | Calcium, insulin-euglycemic therapy, vasopressors, IVF |

| 65M | Opioid unspecified | None listed | No | No | Antihypertensives, opioids, |

| 62F | Ethanol | HT, BC, MI, RD, CNS, MA,AG, OG, GIB, WBC, RBM | No | No | Fomepizole, vasopressors, continuous renal replacement, CPR, intubation, IV fluids |

| 60M | Acetaminophen | None listed | No | No | NAC |

| 32F | Aspirin | HT, BC, VD, RD, CNS, | No | No | NaHCO3, vasopressors, CPR, intubation, IV fluids |

| 32M | Cyanide | RD, CNS, AG, MET | Yes | Yes | Hydroxocobalamin, methylene blue, NaHCO3, vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 44M | Acetaminophen | AP, HPT, MET, MYS, CPT, AKI, RBM | Yes | No | NAC, hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 43M | Methanol | TC, RD, CNS, SZ, MA, AG, OG | Yes | Yes | Folate, fomepizole, thiamine, vasopressors, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluids |

Based on response from medical toxicologist “Did the patient have a toxicological exposure?” equals yes, with known agent(s)

AG anion gap, AGT agitation, AKI acute kidney injury, ALI acute lung injury/ARDS, AP aspiration pneumonia, AVB AV block, BC bradycardia, BP bradypnea, CNS coma/CNS depression, CPT coagulopathy, CRV corrosive injury, DLM delirium, EPS dystonia/rigidity, GIB GI bleeding, HCN hallucinations, HGY hypoglycemia, HPT hepatoxicity, HT hypotension, HTN hypertension, HYS hemolysis, HYT hyperthermia, INT intestinal ischemia, MA metabolic acidosis, MET methemoglobinemia, MI myocardial injury/ischemia, NP neuropathy, OG osmole gap, OTH1 rash, OTH2 skin blisters, necrosis, PCT pancytopenia, PLT thrombocytopenia, PNC pancreatitis, PST paresthesia, QRS QRS prolongation, QTc QTc prolongation, RAD asthma/reactive airway disease, RBM rhabdomyolysis, RD respiratory depression, RFX hyperreflexia/tremor, SZ seizures, TC tachycardia, VD ventricular dysrhythmia, WBC leukocytosis, WKN weakness/paralysis, BAL dimercaprol, CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ECMO extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation, NAC n-acetyl cysteine, NaHCO 3 sodium bicarbonate

aAge in years unless otherwise stated

bPharmcological and non-pharmacological support as reported by medical toxicologist

Table 33.

ToxIC 2016 fatality cases with known toxicological exposure, multiple agents

| Age/sexa | Agents involved | Clinical findings | Life support withdrawn | Brain death confirmed | Treatmentb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45F | Carbon monoxide, cyanide | HT, TC, ALI, RD, CNS, MA, AG, | Yes | Yes | Hydroxocobalamin, intubation |

| 30M | Heroin, cocaine, diphenhydramine, dextromethorphan, citalopram | TC, AP, CNS, RFX, MA, HPT, CPT, WBC, AKI, RBM, OTH2 | Yes | No | NaHCO3, antihypertensives, benzodiazepines, neuromuscular blockers, opioids, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluids |

| 59M | Acetaminophen, ethanol | HT, RD, CNS, HGY, GIB, CPT | Unknown | Unknown | NAC, intubation, IV fluids |

| 16M | Acetaminophen, ethanol | DLM | Unknown | Unknown | None listed |

| 52F | Nicotine, caffeine, dextromethorphan, venlafaxine | VD, QRS, AP, CNS, GIB | Yes | Yes | NAC, NaHCO3, vasopressors |

| 62M | Heroin, cocaine | HT, BC, QTc, ALI, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, AKI, RBM | Yes | Yes | NAC, naloxone, vasopressors, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| 68F | Nortriptyline, duloxetine, zolpidem, oxycodone | HTN, HT, TC, AP, ALI, RD, AGT, DLM, RFX, MA, PNC, PLT, AKI, RBM | Yes | No | Naloxone, vasopressors, benzodiazepines, neuromuscular blockers, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids |

| Unknown F | Fentanyl, diazepam | HT, RD, CNS, MA | Yes | Yes | Vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 15F | Ibuprofen, quetiapine | HT, TC, VD, QRS, RAD, CNS, MA, AG, | Yes | Unknown | Insulin-euglycemic therapy, lipid resuscitation, NaHCO3, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, activated charcoal, hemodialysis, ECMO |

| 32F | Fentanyl, heroin | BC, BP, RD, CNS, SZ, AKI | Yes | No | Naloxone, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 28M | Methadone, marijuana | CNS, SZ, MA | Unknown | Unknown | Benzodiazepines, neuromuscular blockers, intubation, IV fluids |

| 65F | Hydrocodone, alprazolam, diazepam | HT, RD, CNS | Yes | No | Calcium, glucagon, insulin-euglycemic therapy, NAC, naloxone, vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 35M | Olanzapine, valproic acid | HT, TC, AGT, DLM | No | No | NAC, NaHCO3, vasopressors, glucose, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluids |

| 21F | Dextroamphetamine, lithium | AGT, RBM | Unknown | Unknown | IV fluids |

| 33M | Heroin, valproic acid | HT, BC, VD, AP, AP, ALI, RD, CNS | Yes | No | Carnitine, NaHCO3, intubation, IV fluids |

| 50M | Norepinephrine, argatroban | CPT, PLT, WBC, RBM, OTH2 | Yes | Unknown | Vasopressors, continuous renal replacement, intubation, IV fluids, transfusion |

| 70M | Warfarin, methadone, oxycodone, cocaine, heroin | HT, RD, CNS, CPT, AKI | Yes | Yes | Vitamin K, vasopressors, IV fluids |

| 57M | Acetaminophen, metformin | HT, BC, RD, CNS, SZ, MA, AG, HPT, PNC, PLT, AKI | No | No | NAC, vasopressors, anticonvulsants, steroids, continuous renal replacement, CPR, intubation |

| 38M | Methamphetamine, amphetamine, marijuana, benzodiazepine | HTN, TC | No | No | Antihypertensives, benzodiazepines, CPR, intubation |

| 54M | Ethanol, ibuprofen, acetaminophen | HT, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, PLT, AKI | No | No | Fomepizole, NAC, vitamin K, vasopressors, hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement, IV fluids |

| 47M | Oxycodone, alprazolam, diazepam | HT, TC, BC, BP, VD, MI, RD, CNS, MA, AKI | Unknown | Unknown | None listed |

| Unknown M | Cyanide, carbon monoxide | HT, VD, ALI, RD, CNS, AG | Yes | Yes | Hydroxocobalamin, vasopressors, hyperbaric oxygen, intubation, IV fluids |

| 66F | Fentanyl, hydromorphone | BP, RD, CNS, HGY, MA | No | No | Naloxone, glucose, opioids, intubation, IV fluids |

| 77M | Metoprolol, amlodipine | HT, BC, AVB, QRS, ALI, CNS, MA, HPT | Yes | No | Atropine, calcium, glucagon, insulin-euglycemic therapy, vasopressors, glucose, neuromuscular blockers, intubation, IV fluids |

| 53F | Insulin, zolpidem, venlafaxine | AP, CNS | Yes | Yes | Glucagon, naloxone, glucose, intubation, IV fluids |

| 56M | Cocaine, opioid unspecified | MI, AP, RD, CNS, AKI, RBM | Yes | No | Antihypertensives, benzodiazepines, glucose, opioids, intubation, IV fluids |

| 53F | Amlodipine, toluene, doxepin, carisoprodol, clonazepam | HT, BC, VD, QTc, QRS, RD, CNS, RFX, HGY | No | No | Calcium, methylene blue, naloxone, NaHCO3, methylene blue, naloxone, NaHCO3, thiamine, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, benzodiazepines, glucose, steroids, intubation, IV fluids |

| 41F | Iron, diphenhydramine | HT, TC, BP, VD, ALI, CNS, MA, AG, HPT | No | No | NaHCO3, deferoxamine, vasopressors, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluids |

| 21F | Hydroxyzine, fluoxetine, melatonin | HT, BP, QTc, RD, CNS, MA, AG, HPT, CPT, AKI, RBM | No | No | NAC, naloxone, vasopressors, CPR, cardioversion, intubation, IV fluids, therapeutic hypothermia |

| 43F | Heroin, cocaine | VD, RD, CNS | Yes | Yes | NaHCO3, vasopressors, intubation, IV fluids |

| 14M | Bupropion, fluoxetine, meclizine | HT, TC, BC, BP, VD, QTc, AP, AGT, CNS, SZ, RFX, MA, RBM | Yes | No | Lipid resuscitation, vasopressors, antiarrhythmics, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, neuromuscular blockers, opioids, CPR, ECMO, intubation |

| 57M | Acetaminophen, metformin | HT, CNS, SZ, HGY, MA, AG, HPT, CPT, WBC, AKI, RBM | No | No | NAC, vitamin K, vasopressors, benzodiazepines, steroids, continuous renal replacement, intubation, transfusion |

| 64M | Cyclobenzaprine, gabapentin, acetaminophen, codeine | CNS, AG | Yes | Yes | Naloxone, physostigmine |

| 53M | Metformin, atenolol | HTN, HT, QTc, QRS, MI, MA, AG, HPT, AKI, RBM | No | No | Calcium, lipid resuscitation, NaHCO3, vasopressors, activated charcoal, hemodialysis, intubation, IV fluids |

Based on response from medical toxicologist “Did the patient have a toxicological exposure?” equals yes, with known agent(s)

AG anion gap, AGT agitation, AKI acute kidney injury, ALI acute lung injury/ARDS, AP aspiration pneumonia, AVB AV block, BC bradycardia, BP bradypnea, CNS coma/CNS depression, CPT coagulopathy, CRV corrosive injury, DLM delirium, EPS dystonia/rigidity, GIB GI bleeding, HCN hallucinations, HGY hypoglycemia, HPT hepatoxicity, HT hypotension, HTN hypertension, HYS hemolysis, HYT hyperthermia, INT intestinal ischemia, MA metabolic acidosis, MET methemoglobinemia, MI myocardial injury/ischemia, NP neuropathy, OG osmole gap, OTH1 rash, OTH2 skin blisters, necrosis, PCT pancytopenia, PLT thrombocytopenia, PNC pancreatitis, PST paresthesia, QRS QRS prolongation, QTc QTc prolongation, RAD asthma/reactive airway disease, RBM rhabdomyolysis, RD respiratory depression, RFX hyperreflexia/tremor, SZ seizures, TC tachycardia, VD ventricular dysrhythmia, WBC leukocytosis, WKN weakness/paralysis, BAL dimercaprol, CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ECMO extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation, NAC n-acetyl cysteine, NaHCO 3 sodium bicarbonate

aAge in years unless otherwise stated

bPharmcological and non-pharmacological support as reported by medical toxicologist

The number of fatalities increased again in 2016 to 126, along with an increased percentage of cases reporting a fatality (1.5%), up from 98 fatalities (1.2%) in 2015, and 89 fatalities (1.0%) in 2014 [2, 7]. Of these 126 fatalities, 63 (0.7%) involved single agent exposures and 35 (0.4%) cases involved multiple agent exposures. The remaining 28 (0.3%) fatalities were categorized as not a toxicological exposure, or unknown with respect to toxicity and presentation and are presented in Table S18.

Six fatalities (four females, two males) involved pediatric (age 0–18 year) patients. All six were adolescents, with ages ranging from 14 to 17 years, constituting 4.8% of fatalities. Five of these were intentional pharmaceutical exposures, with some intent to self-harm, and four were reported as definitive suicide attempts. An additional case reported toxicology involvement to assist with interpretation of lab data and evaluation of malicious or criminal intent. Three pediatric fatalities involved single agents (bupropion, cocaine, and diphenhydramine) and three involved multiple agents (acetaminophen, bupropion, ethanol, fluoxetine, ibuprofen, meclizine, and quetiapine). Life support measures were withdrawn in five of the six pediatric fatality cases. The sixth case is reported as unknown whether life support was withdrawn in a 16-year-old male with an exposure to acetaminophen and ethanol, and no treatment interventions are listed. This entry was categorized as misuse or abuse of a substance by taking higher doses than recommended of an over the counter product without an attempt at self-harm. No further details were provided to describe the lack of interventions or treatments recorded such as pronounced on arrival, or family or religious preference.

Among the single agent fatalities (all ages), there were four deaths attributed to ethanol; of these, three were intubated and mechanically ventilated and received either continuous renal replacement or hemodialysis. Eight single agent fatalities (age range 21–51 years) were attributed to heroin and one to fentanyl (a 19-year-old). Of the multiple agent fatalities, six involved heroin and three involved fentanyl. Fourteen fatalities overall were single agent exposures to opioids, while 15 multiple agent fatalities involved one or more opioids including 4 cases involving a combination of cocaine with heroin or other opioid.

Life support measures were withdrawn in 60 (61.2%) of the fatalities related to a toxicologic exposure (single or multi-agent), with brain death confirmed in 26 (43.3%). The 60 patients ranged in age from 14 to 80 years (including 5 pediatric patients), with two patients of unknown age. The mean and median ages for those with life support withdrawn were 44.6 and 43.5 years, respectively, with a sex distribution of 55.0% male and 45.0% female.

Adverse Drug Reactions

Table 34 presents information on adverse drug reactions (ADRs). In 2016, there were 320 cases (3.8% of Registry cases) that were categorized as ADRs, defined as any unintended response to a medication as used in standard therapeutic dosing. There were 455 total agent entries with 164 unique agents. Some cases reported multiple agents, possibly reflecting drug-drug interactions. The strength of association between the reported agent and the clinical presentation was recorded as definitive by rechallenge in 4.7% of cases, probable in 72.8%, and possible in 22.5%. The most frequently recorded drugs in ADR cases in 2016 were lithium (11.9%) and digoxin (5.9%).

Table 34.

ToxIC 2016—most common drugs associated with ADRs

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Lithium | 38 (11.9) |

| Digoxin | 19 (5.9) |

| Haloperidol | 14 (4.4) |

| Metformin | 13 (4.1) |

| Metoprolol | 12 (3.8) |

| Phenytoin | 12 (3.8) |

| Valproic acid | 12 (3.8) |

| Acetaminophen | 9 (2.8) |

| Olanzapine | 9 (2.8) |

| Sertraline | 8 (2.5) |

ADRs adverse drug reactions

aPercentages are calculated out of the total number of cases reporting an ADR (N = 320)

Treatment

In 2016, there were 3047 cases (35.7% of total Registry cases) with at least one antidote administered, and 3540 antidotes given overall (Table 35). Similar to prior years, N-acetylcysteine was the most common, accounting for more than one quarter of antidotes given in 2016 (27.5%), followed by naloxone/nalmefene (19.9%), and sodium bicarbonate (11.9%). In 2016, 2.7% of Registry cases reported antivenom therapy, with the vast majority of these (96.1%) receiving Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab (ovine), again reflecting the presence of the North American Snake Bite Registry within the overall Registry (Table 36).

Table 35.

Antidotal therapy administered in ToxIC in 2016

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| N-Acetylcysteine | 974 (27.5) |

| Naloxone/nalmefene | 705 (19.9) |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 421 (11.9) |

| Thiamine | 250 (7.1) |

| Folate | 201 (5.7) |

| Physostigmine | 147 (4.2) |

| Fomepizole | 119 (3.4) |

| Calcium | 110 (3.1) |

| Glucagon | 98 (2.8) |

| Flumazenil | 63 (1.8) |

| Cyproheptadine | 58 (1.6) |

| Vitamin K | 51 (1.4) |

| Atropine | 47 (1.3) |

| L-Carnitine | 44 (1.3) |

| Insulin-euglycemic therapy | 44 (1.3) |

| Octreotide | 44 (1.3) |

| Fab for digoxin | 34 (1.0) |

| Lipid resuscitation | 25 (0.8) |

| Pyridoxine | 26 (0.7) |

| Hydroxocobalamin | 17 (0.5) |

| Methylene blue | 14 (0.4) |

| Dantrolene | 9 (0.3) |

| 2-PAM | 7 (0.2) |

| Bromocriptine | 6 (0.2) |

| Thiosulfate | 6 (0.2) |

| Anticoagulation reversal | 5 (0.1) |

| Botulinum antitoxin | 3 (0.1) |

| Ethanol | 2 (0.1) |

| Nitrites | 2 (0.1) |

| Coagulation factor replacement | 1 (<0.1) |

| Protamine | 1 (<0.1) |

| Total | 3540 (100) |

aPercentages are out of the total number of antidotes administered (N = 3540); 3047 cases (35.7% of total Registry cases) received at least one antidote; some cases involve multiple antidotes

Table 36.

Antivenom therapy administered in ToxIC in 2016

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Crotalidae polyvalent immune fab (ovine) | 222 (96.1) |

| Other snake antivenom | 5 (2.2) |

| Scorpion antivenom | 3 (1.3) |

| Spider antivenom | 1 (0.4) |

| Total | 231 (100) |

aPercentages are out of the total number of antivenom treatments administered (N = 231)

Tables 37 and 38, respectively, summarize the pharmacological and non-pharmacological supportive care intervention frequencies in 2016. A total of 3830 pharmacological and 4522 non-pharmacological supportive care interventions were reported. There were 2741 cases (32.1% of total Registry cases) reporting at least one form of pharmacologic treatment and 3508 cases (41.1% of total Registry cases) reporting at least one non-pharmacological intervention. Some cases involved more than one form of treatment. Similar to past years, benzodiazepines were used in half of the pharmacological interventions, followed by opioids (10.8%), vasopressors (10.3%), and antipsychotics (7.2%). Of the non-pharmacological interventions, intravenous fluid resuscitation was the most common (70.3%), followed by intubation and ventilatory management (25.1%).

Table 37.

Supportive care interventions administered in ToxIC in 2016—pharmacological

| N (%)a | |

|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | 1917 (50.1) |

| Opioids | 415 (10.8) |

| Vasopressors | 393 (10.3) |