Abstract

CLE peptide hormones are critical regulators of many cell proliferation and differentiation mechanisms in plants. These 12-13 amino acid glycosylated peptides play vital roles in a diverse range of plant tissues, including the shoot, root and vasculature. CLE peptides are also involved in controlling legume nodulation. Here, the entire family of CLE peptide-encoding genes was identified in Medicago truncatula (52) and Lotus japonicus (53), including pseudogenes and non-functional sequences that were identified. An array of bioinformatic techniques were used to compare and contrast these complete CLE peptide-encoding gene families with those of fellow legumes, Glycine max and Phaseolus vulgaris, in addition to the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. This approach provided insight into the evolution of CLE peptide families and enabled us to establish putative M. truncatula and L. japonicus orthologues. This includes orthologues of nodulation-suppressing CLE peptides and AtCLE40 that controls the stem cell population of the root apical meristem. A transcriptional meta-analysis was also conducted to help elucidate the function of the CLE peptide family members. Collectively, our analyses considerably increased the number of annotated CLE peptides in the model legume species, M. truncatula and L. japonicus, and substantially enhanced the knowledgebase of this critical class of peptide hormones.

Introduction

CLAVATA3/Endosperm Surrounding Region-related (CLE) peptides belong to a class of cysteine poor, post-translationally modified peptides that are derived from a prepropeptide1–3. The mature CLE peptide is 12 to 13 amino acids long and those that have been structurally confirmed all possess a tri-arabinose moiety attached to a highly conserved hydroxylated central proline residue4–6. They act as hormone-like signals7 and are perceived by class XI leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases8. They are also unique to plants, with the exception of CLE peptide-encoding genes of the cyst-knot nematode9, which were likely acquired from plants via horizontal gene transfer6,10. CLE peptides have roles in regulating stem cell populations of various plant organs11,12. Prominent examples include CLAVATA3 (CLV3) in the shoot apical meristem13–15, AtCLE40 in the root apical meristem16–18, a number of legume-specific CLE peptides that suppress nodule organogenesis2,19, and a sub-class of highly conserved CLE peptides that regulate vascular differentiation20–24. Those of the cyst-knot nematode are thought to have a role in establishing the pathogen’s feeding site25.

Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus are model legume species that offer a number of molecular advantages to understanding aspects of legume development, as well as microbial and fungal symbioses26. However, only a few CLE peptide-encoding genes have been functionally characterised in these species to date. This includes LjCLE-RS1, LjCLE-RS2, LjCLE-RS3, MtCLE12 and MtCLE13, which are involved in nodulation regulation2,5,27–29. Others include LjCLE7, LjCLE15, LjCLE19 LjCLE20, LjCLE24 and LjCLE29, that are up-regulated in response to phosphate and/or mycorrhizae30,31; and MtCLV3 32 and LjCLV3 27,33, the orthologues of the most thoroughly characterised CLE peptide-encoding gene, AtCLV3 15. In M. truncatula, the likely orthologues of the Treachery Element Inhibitory Factor (TDIF) encoding genes, AtCLE41, AtCLE42 and AtCLE44 23,24, have also been identified3.

Recent genomic and bioinformatic advances allow for the identification of entire peptide families. This is extremely helpful for comparable genomic studies and for advancing the important functional characterisation of individual peptide members. Here, we used a genome-wide approach to identify the complete CLE peptide-encoding gene families of M. truncatula and L. japonicus. Comparative bioinformatic approaches were used to assist in identifying orthologous genes between these, and other plant species, as well as in the categorisation and functional characterisation of these critical peptide-encoding genes.

Results

Identification of CLE peptide-encoding genes in L. japonicus and M. truncatula

A thorough genome-wide search of the M. truncatula and L. japonicus genomes was conducted to identify the complete CLE peptide-encoding gene families of these species. Multiple BLAST searches identified 52 and 53 CLE peptide-encoding genes in each of the two species respectively (Figs 1–3, Table 1). Initial BLAST and TBLASTN queries used sequences of known soybean and A. thaliana CLE peptide-encoding genes and prepropeptides3 to ensure all genes of interest were captured. The resulting identified sequences were verified and false-positives removed from further analyses. Additional CLE peptide-encoding genes were identified by BLAST and TBLASTN reciprocal searches of the M. truncatula and L. japonicus genomes using the sequences identified in the initial searches. A number of the genes identified are reported here for the first time, with the nomenclature of the newly discovered genes consistent with previously identified CLE peptide-encoding genes (Figs 1–3, Table 1). A recent study published after our searches were conducted included 20 M. truncatula CLE peptide-encoding genes (Goad et al., 2016), but no nomenclature was given as species-specific analyses were not conducted. A complete listing of all CLE peptide encoding gene family members from M. truncatula and L. japonicus is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

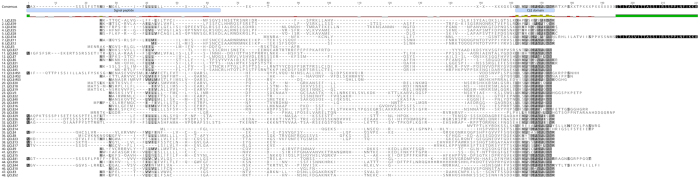

Figure 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of Medicago truncatula CLE prepropeptides. The sequences show high similarity, as indicated by darker shading, in the signal peptide and CLE domains. Not shown are the multi-CLE domain containing prepropeptides (MtCLE14, MtCLE26, MtCLE27 and MtCLE22, see Fig. 3) and MtCLE19, which has a premature stop codon very early in the prepropeptide (see Fig. 4). MtCLE34 is a likely pseudogene without a functional CLE domain. The signal peptide approximate location and CLE domain is shown on the consensus sequence.

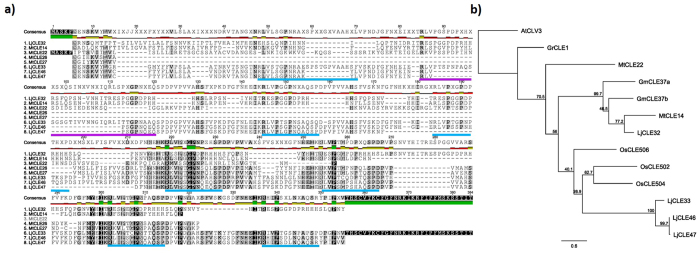

Figure 3.

Multi-CLE domain prepropeptides. (a) Multiple sequence alignment of four Lotus japonicus (LjCLE32, LjCLE33, LjCLE46 and LjCLE47) and four Medicago truncatula (MtCLE14, MtCLE26, MtCLE27 and MtCLE22) multi-CLE domain containing prepropeptides (See Supplementary Table S3). Putative CLE domains are located above the blue and purple underlined regions. LjCLE21, LJCLE33 and MtCLE14 also have a second CLE domain present above the purple underlined region. (b) Phylogenetic tree of known multi-CLE domain prepropeptides in L. japonicus, M. truncatula, Glycine max, Oryza sativa and potato cysts nematode (Globodera rostochiensis), including AtCLV3 as an outgroup. The tree is shown with bootstrap confidence values as a percentage of 1,000 bootstraps.

Table 1.

Name, ID and various features of CLE genes in Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus.

| Name | Phytozome V11 ID (Mtv4) | Pre-propeptide length | Chromosome location | Orientation | Predicted intron | SP cleavage sitea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MtCLE1/CLE25 | Medtr5g037140 | 110 | chr5:16209190..16209492 | forward | No | 39 |

| MtCLE02 | Medtr6g009390 | 90 | chr6:2758371..2758643 | reverse | No | 34 |

| MtCLE03 | Medtr1g110820 | 99 | chr1:50033208..50033507 | forward | No | 31 |

| MtCLE04 | Medtr5g014860 | 66 | chr5:5053422..5053622 | reverse | No | 26 |

| MtCLE05 | Medtr1g100733 | 84 | chr1:45667039..45667293 | forward | No | 25 |

| MtCLE06 | Medtr7g058790 | 99 | chr7:21150139..21150438 | reverse | No | 35 |

| MtCLE07 | Medtr7g089320 | 85 | chr7:34939800..34940057 | forward | No | 28 |

| MtCLE08 | Medtr8g076990 | 120 | chr8:32679901..32680263 | reverse | No | 27 |

| MtCLE09 | Medtr7g084110 | 137 | chr7:32430490..32430903 | reverse | No | 31 |

| MtCLE10 | Medtr6g054925 | 74 | chr6:19620161..19620385 | forward | No | 27 |

| MtCLE11 | Medtr3g037730 | 83 | chr3:13874060..13874311 | reverse | No | 27 |

| MtCLE12 | Medtr4g079630 | 81 | chr4:30800344..30800589 | forward | No | 29 |

| MtCLE13 | Medtr4g079610 | 84 | chr4:30793797..30794051 | forward | No | 27 |

| MtCLE14 | Medtr7g084100 | 221 | chr7:32428499..32429164 | reverse | No | 28 |

| MtCLE15 | Medtr2g087170b | 100 | chr2:36639989..36640517 | forward | Yes | 26 |

| MtCLE16 | Medtr5g043830 | 101 | chr5:19252630..19252935 | reverse | No | 20 |

| MtCLE17 | Medtr5g085990 | 72 | chr5:37176921..37177139 | reverse | No | 21 |

| MtCLE18 | Medtr1g093800 | 104 | chr1:42088638..42088952 | forward | No | 27 |

| MtCLE19 | unannotated | c | chr7:46832505..46832810 | forward | No | ND |

| MtCLE20 | Medtr1g018700 | 91 | chr1:5449791..5450066 | forward | No | 43 |

| MtCLE21 | Medtr5g089080 | 84 | chr5:38716369..38716623 | forward | No | 27 |

| MtCLE22 | Medtr2g087180 | 181 | chr2:36645611..36646743 | reverse | Yes | 26 |

| MtCLE23 | Medtr3g080060 | 72 | chr3:36207269..36207487 | forward | No | 24 |

| MtCLE24 | Medtr5g040640 | 108 | chr5:17857512..17857838 | reverse | No | 27 |

| MtCLE26 | unannotated | 117 | chr1:27528684..27529037 | forward | No | 22 |

| MtCLE27 | Medtr1g062850 | 116 | chr1:27531440..27531790 | forward | No | 22 |

| MtCLE28 | Medtr1g106920 | 89 | chr1:48060869..48061138 | forward | No | 23 |

| MtCLE29 | Medtr2g015445 | 78 | chr2:4575877..4576113 | forward | No | 24 |

| MtCLE30 | Medtr2g038665 | 81 | chr2:16905712..15905957 | reverse | No | 22 |

| MtCLE31 | Medtr2g078130 | 85 | chr2:32437536..32437793 | reverse | No | 26 |

| MtCLE32 | Medtr2g078140 | 83 | chr2:32444505..32444756 | reverse | No | 22 |

| MtCLE33 | Medtr2g078160 | 75 | chr2:32460085..32460212 | reverse | No | 22 |

| MtCLE34 | Medtr2g091120 | 49 | chr2:39236945..39237094 | forward | No | 23 |

| MtCLE35 | Medtr2g091125 | 92 | chr2:39246810..39247088 | forward | No | 24 |

| MtCLE36 | Medtr2g437780 | 108 | chr2:14915100..14915427 | forward | No | 27 |

| MtCLE37 | Medtr2g437800 | 108 | chr2:14923591..14923917 | forward | No | 27 |

| MtCLE38 | Medtr4g051618 | 75 | chr4:18583841..18584193 | reverse | Yes | 22 |

| MtCLE39 | Medtr4g066100 | 82 | chr4:24906117..24906560 | reverse | Yes | 21 |

| MtCLE40 | Medtr4g082920 | 92 | chr4:32235471..32235749 | reverse | No | 25 |

| MtCLE41 | Medtr4g084520 | 114 | chr4:32892006..32892350 | reverse | No | 32 |

| MtCLE42 | Medtr4g087850 | 74 | chr4:34563502..34563726 | reverse | No | 23 |

| MtCLE43 | unannotated | 117 | chr4:34572155..34572508 | reverse | No | 22 |

| MtCLE44 | Medtr4g126940 | 89 | chr4:52604820..52605086 | reverse | No | 19 |

| MtCLE45 | Medtr5g056935 | 84 | chr5:23427594..23427848 | reverse | No | 32 |

| MtCLE46 | Medtr7g084130 | 98 | chr7:32437149..32437445 | reverse | No | 27 |

| MtCLE47 | unannotated | 126 | chr7:32590148..32590528 | reverse | No | 28 |

| MtCLE48 | unannotated | 87 | chr7:32594246..32594509 | reverse | No | ND |

| MtCLE49 | Medtr7g093050 | 92 | chr7:36960868..36961146 | reverse | No | 27 |

| MtCLE50 | Medtr7g094080 | 81 | chr7:37442023..37442268 | forward | No | 24 |

| MtCLE51 | Medtr8g042980 | 78 | chr8:16651803..16652039 | forward | No | 20 |

| MtCLE52 | Medtr8g096970 | 89 | chr8:40711987..40712256 | reverse | No | 25 |

| MtCLE53 | Medtr8g463700 | 82 | chr8:22459174..22469422 | forward | No | 26 |

| LjCLE3 | Lj4g3v2140240.1 | 81 | chr4:29668322..29668567 | forward | No | 19 |

| LjCLE4 | Lj5g3v0296280.1 | 87 | chr5:2776799..2777062 | reverse | No | 28 |

| LjCLE5 | Unannotated | 37 | chr0:191639..191752 | reverse | No | 14 |

| LjCLE6 | Lj2g3v2904560.1 | 77 | chr2:37869993..37870226 | reverse | No | 28 |

| LjCLE7 | Lj5g3v2013980.1 | 85 | chr5:28436402..28436659 | forward | No | 26 |

| LjCLE8 | Lj1g3v4106880.1 | 90 | chr1:48730186..48730458 | forward | No | 29 |

| LjCLE9 | Lj2g3v1155200.1 | 84 | chr2:18195792..18196046 | reverse | No | 30 |

| LjCLE10 | Lj2g3v1984000.1 | 58 | chr2:28901709..28901885 | reverse | No | 20 |

| LjCLE11 | Lj4g3v2917660.1 | 91 | chr4:38847122..38847397 | reverse | No | 28 |

| LjCLE12 | unannotated | 78 | chr4:38846082..38846318 | reverse | No | ND |

| LjCLE13 | Lj5g3v1494620.1 | 77 | chr5:21653524..21653754 | reverse | No | 31 |

| LjCLE14 | Lj3g3v1261020.1 | 71 | chr3:16238530..16238742 | forward | No | ND |

| LjCLE15 | Lj5g3v1789230.1 | 104 | chr5:25374552..25374863 | forward | No | 27 |

| LjCLE16 | Lj6g3v1996000.1 | 75 | chr6:23228716..23228940 | reverse | No | 21 |

| LjCLE17 | Lj1g3v4931750.1 | 74 | chr1:60060788..60061012 | forward | No | 27 |

| LjCLE18 | Lj3g3v1063710.1 | 80 | chr3:14363293..14363535 | reverse | No | 26 |

| LjCLE19 | Lj3g3v0428680.1 | 84 | chr3:4038516..4038770 | reverse | No | 28 |

| LjCLE20 | Lj3g3v0428740.1 | 83 | chr3:4052954..4053205 | reverse | No | 27 |

| LjCLE21 | Lj6g3v1055570.1 | 73 | chr6:12069820..12070041 | reverse | No | 22 |

| LjCLE22 | Lj0g3v0114139.1 | 76 | chr0:49962922..49963152 | forward | No | 23 |

| LjCLE23 | Lj0g3v0005899.1 | 96 | chr0:2220612..2220902 | reverse | No | 35 |

| LjCLE24 | Lj4g3v0496580.1 | 110 | chr4:8347397..8347729 | forward | No | 22 |

| LjCLE25 | Lj4g3v1635250.1 | 94 | chr4:24032504..24032788 | reverse | No | 27 |

| LjCLE26 | Lj4g3v0189810.1 | 122 | chr4:2377271..2377630 | forward | No | 33 |

| LjCLE27 | Lj2g3v0276540.1 | 86 | chr2:4685035..4685295 | forward | No | 21 |

| LjCLE28 | Lj1g3v0492090.1 | 95 | chr1:6477403..6477690 | forward | No | 20 |

| LjCLE29 | Lj2g3v1389560.1 | 99 | chr2:22031058..22031357 | forward | No | 40 |

| LjCLE30 | Lj2g3v1277900.1 | 109 | chr2:20511088..20511417 | forward | No | 23 |

| LjCLE31 | Lj6g3v1415960.1 | 124 | chr6:16797110..16797364 | reverse | No | 31 |

| LjCLE32 | Unannotated | 274 | chr1:45492391..45493215 | reverse | No | 27 |

| LjCLE33 | Lj3g3v1314940.1 | 347 | chr3:17115763..17116806 | forward | No | ND |

| LjCLE34 | Lj3g3v2248290b | 89 | chr3:126894445..126894714 | forward | No | 26 |

| LjCLE35 | Unannotated | 79 | chr5:30013235..30013474 | forward | No | 19 |

| LjCLE37 | Unannotated | 44 | chr6:16475826..16475960 | reverse | No | ND |

| LjCLE38 | Lj1g3v4241120.1 | 77 | chr1:50124894..50125127 | reverse | No | ND |

| LjCLE39 | Lj1g3v4317570.1 | 93 | chr1:50801119..50801398 | reverse | No | 29 |

| LjCLE40 | Lj3g3v2848710.1 | 80 | chr3:35016355..35016597 | forward | No | 22 |

| LjCLE41 | Lj2g3v1354640.1 | 98 | chr2:21357987..21358244 | forward | No | 32 |

| LjCLE42 | Lj4g3v0643890.1 | 111 | chr4:10320058..10320393 | forward | No | 41 |

| LjCLE43 | Unannotated | 96 | chr0:78808582..78808872 | forward | No | 24 |

| LjCLE44 | Lj2g3v1022600.3 | 100 | chr2:16174090..16174392 | reverse | No | 29 |

| LjCLE45 | Lj2g3v1265080.1 | 96 | chr2:20113738..20114028 | forward | No | 21 |

| LjCLE46 | Lj3g3v1314910.1 | 285 | chr3:17104803..17105660 | reverse | No | 27 |

| LjCLE47 | Lj3g3v1314920.1 | 250 | chr3:17108302..17109054 | reverse | No | 27 |

| LjCLE48 | Unannotated | c | chr3:40213173..40213683 | forward | Yesc | ND |

| LjCLE49 | Lj4g3v0496650.1 | 74 | chr4:08364934..08365729 | forward | No | 26 |

| LjCLE50 | Lj4g3v1785920.1 | 102 | chr4:25243942..25244250 | reverse | No | 25 |

| LjCLE51 | Lj5g3v2193950.1 | 98 | chr5:31824885..23948823 | forward | No | 30 |

| LjCLE52 | Lj6g3v1280830.1 | 82 | chr6:15475896..15476144 | reverse | No | 19 |

| LjCLE-RS1 | Lj0g3v0000559.1 | 116 | chr0:240796..241074 | reverse | No | 23 |

| LjCLE-RS2 | Lj3g3v2848800.1 | 81 | chr3:35039780..35040025 | forward | No | 28 |

| LjCLE-RS3 | Lj3g3v2848810.1 | 72 | chr3:35048895..35049113 | forward | No | 28 |

| LjCLV3 | Lj3g3v1239970.1 | 105 | chr3:16182605..16182777 | forward | Yes | 24 |

aSignal peptide cleaved after noted residue. bUnannotated transcript variant. cLikely untranscribed pseudogene. ND, not detected.

Additional CLE peptide-encoding genes in both L. japonicus and M. truncatula were identified that contain multiple CLE domains; some of which are also reported here for the first time. These multi-CLE peptide domain encoding genes include LjCLE32, LjCLE33, LjCLE46 and LjCLE47 in L. japonicus; and MtCLE14, MtCLE22, MtCLE26 and MtCLE27 in M. truncatula (Fig. 3). LjCLE32 and LjCLE33 encode eight and nine putative CLE peptides respectively; MtCLE22 encodes four putative CLE peptides; MtCLE26 and MtCLE27 encode three putative CLE peptides; whereas all others contain seven putative CLE peptide domains (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Table S1). Interestingly, these multi-CLE domain containing genes contain repeating motifs of 24 to 35 amino acids, with each motif having a consistent length within their respective prepropeptide, with the sole exception of LjCLE33 which has varying motif lengths (Supplementary Table S2).

Pseudogenes were also identified in both the L. japonicus and M. truncatula genomes. These genes include mutations where the CLE domain is not translated in frame, likely resulting in a non-functional gene. This includes the pseudogenes MtCLE34, which is annotated within the M. truncatula genome (Fig. 1, Table 1; Supplementary Fig. S1) and MtCLE19 (Fig. 4). In L. japonicus, LjCLE5 (Figs 2 and 5, Table 1) and LjCLE48 are also unlikely to be functional (Fig. 6). These pseudogenes, and the genes containing multiple CLE-domains, were excluded from the sequence characterisation studies detailed below because they fail to align well with the more typical single-CLE domain sequences.

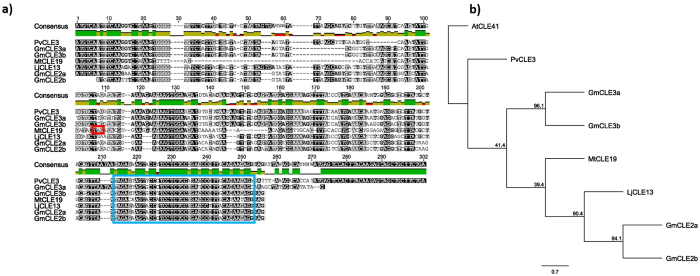

Figure 4.

Genomic sequence characterisation of MtCLE19, the likely non-functional M. truncatula orthologue of GmCLE2a, GmCLE2b, and LjCLE13. (a) Multiple sequence alignment demonstrating that MtCLE19 exhibits high similarity to GmCLE2a, GmCLE2b, and LjCLE13, with slightly less similarity to GmCLE3a, GmCLE3b and PvCLE3. The red box indicates a premature stop codon and the blue box indicates the CLE domain. Grey nucleotides are semi-conserved and black nucleotides are 100% conserved. (b) Phylogenetic tree with bootstrap confidence values expressed as a percentage of 1,000 bootstrap replications, using AtCLE41 as an outgroup.

Figure 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of Lotus japonicus CLE prepropeptides. As with the M. truncatula sequences (Fig. 1), the L. japonicus sequences show high similarity in the signal peptide and CLE domains, as indicated by darker shading. Not shown are the multi-CLE domain containing prepropeptides (LjCLE32, LjCLE33, LjCLE46 and LjCLE47; see Fig. 3) and LjCLE48, the truncated L. japonicus AtCLE40 orthologue as it shows very little amino acid conservation. LjCLE5 is a likely pseudogene without a functional CLE domain (see Fig. 5). The signal peptide approximate location and CLE domain is shown on the consensus sequence.

Figure 5.

Multiple sequence alignment of the prepropeptides of AtCLE18 and LjCLE34. CLE domains are highlighted with a red box and the CLEL domain is underlined in blue. Conservation between amino acid residues of the two sequences is represented by grey (partial) and black (100%) shading.

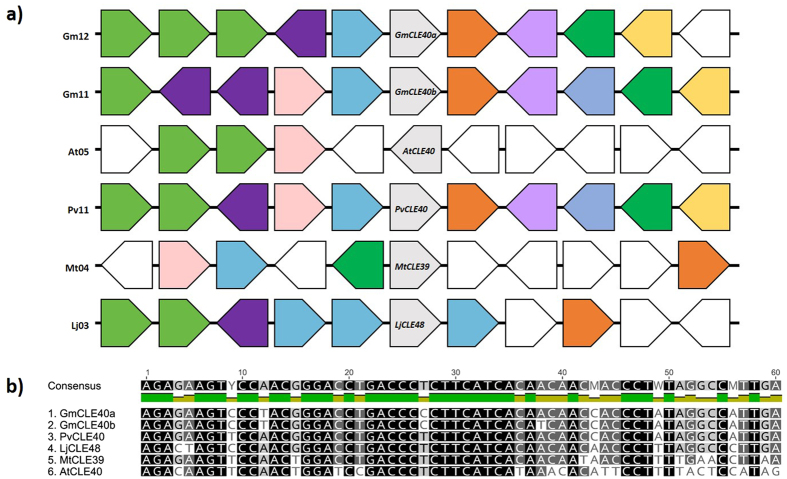

Figure 6.

AtCLE40 and orthologues in Medicago truncatula, Phaseolus vulgaris, and Glycine max, in addition to the truncated orthologue in Lotus japonicus, LjCLE48. (a) The genomic environment of each shows strong synteny. Arrows represent individual genes and their transcriptional direction in relation to CLE40. Similar colours represent genes from the same family, and are typically orthologous. (b) A multiple sequence alignment of the CLE40 domain coding region. Shading represents conservation amongst nucleotides with grey nucleotides semi-conserved and black nucleotides 100% conserved.

A BLAST search of the L. japonicus genome with the LjCLE34 nucleotide sequence (first reported by Okamoto et al.27), identified two possible genes having two synonymous nucleotide changes that result in identical prepropeptides. These genes are located at chr3:27855838..27856107 and chr0:126894445..126894714, and interestingly, both are found within a larger predicted protein. It therefore appears that these two genes arose as a transposable element and subsequent duplication event, or they are the result of a genome sequencing error. Interestingly, the CLE domain of LjCLE34 is not located at the C-terminus of the prepropeptide but towards the centre, similar to that of AtCLE18, which has a C-terminal CLE-Like/Root Growth Factor/GOLVEN (CLEL/RGF/GLV) domain in addition to a CLE domain34. LjCLE34 shares some homology at the C-terminus with AtCLE18 which includes the region of the CLEL/RGF/GLV domain (Supplementary Fig. S2).

CLE peptide-encoding genes of M. truncatula and L. japonicus are located across all chromosomes, with the greatest number located on chromosome two of M. truncatula (eleven) and chromosome three of L. japonicus (thirteen) (Table 1). There are five CLE peptide-encoding genes of L. japonicus currently located on unassigned scaffolds (Table 1). The CLE prepropeptides of both species vary in length, with the average single-CLE domain prepropeptide being 88 residues in L. japonicus and 91 residues in M. truncatula. The multi-CLE domain prepropeptides of both species range from 116 to 347 amino acids.

Some CLE peptide-encoding genes appear directly in tandem within the genome. For example, on chromosome 2 of M. truncatula, MtCLE31 is 6.7 Kb upstream of MtCLE32, which itself is 15.3 Kb upstream of MtCLE33. Also on chromosome 2, MtCLE34 is 9.6 Kb upstream of MtCLE35 and MtCLE36 is 6.7 Kb upstream of MtCLE37. On chromosome 7, MtCLE14, MtCLE09 and MtCLE46 are all within 9 Kb, and MtCLE47 is 3.7 Kb upstream of MtCLE48. On chromosome 4, MtCLE12 and MtCLE13 are not directly in tandem, but are only 6.3 Kb apart (Table 1). On chromosome 3 of L. japonicus, LjCLE46 is 2.6 Kb apart from LjCLE47, which is 6.7 Kb upstream of LjCLE33. Also on chromosome 3, LjCLE40, LjCLE-RS2 and LjCLE-RS3 are within 24 Kb, and although not directly in tandem, LjCLE19 and LjCLE20 are only 14.2 Kb apart. On chromosome 4, LjCLE11 and LjCLE12 are only 0.8 Kb apart (Table 1). Interestingly, the genes appearing directly in tandem within the L. japonicus genome share >50% amino acid sequence similarity, while only some of the tandem gene pairs in M. truncatula exhibit more than a 50% level of similarity (Supplementary Table S3).

Identification of orthologous CLE peptide sequences

To identify gene orthologues of the M. truncatula and L. japonicus CLE prepropeptides, multiple sequence alignments were generated. Most orthologues were present in a 1:1 ratio between the two species (Supplementary Fig. S3). When no orthologue was evident, further BLAST searches were conducted in an attempt to identify one. In some instances, this yielded additional CLE peptide-encoding genes. Subsequent multiple sequence alignments with the CLE prepropeptides of M. truncatula, L. japonicus, soybean, common bean and A. thaliana were constructed (data not shown) and used to identify additional CLE peptide-encoding genes. All orthologous sequences identified are shown in Figs 1 and 2.

A multiple sequence alignment of the prepropeptides of M. truncatula, L. japonicus, common bean and A. thaliana was used to construct a phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. S3). Similar phylogenetic trees have been constructed using only the CLE domain of the prepropeptides; however, this domain is highly conserved and only 12-14 amino acids long, and hence alignments and trees constructed using only the conserved motif can be less informative. In contrast, the tree constructed here, using the entire prepropeptide sequences, allows for the identification of conserved residues within other domains that may relate to cleavage and other important facets of post-translational modification2.

Characterisation of M. truncatula and L. japonicus CLE prepropeptides

The domain structure of all CLE prepropeptides includes a hydrophobic signal peptide near the N-terminus, followed by a large variable region and a short but highly conserved CLE domain (with a multi-CLE domain occasionally present) and a small number (11 in L. japonicus and 8 in M. truncatula) that have a short C-terminal extension of unknown function (Figs 1 and 2)2. The amino acid composition of all known CLE prepropeptides, across legume and non-legume species, is typically rich in lysine and serine, and poor in tyrosine, cysteine and tryptophan, with the latter being poorly represented in all plant proteins3. The CLE prepropeptides of M. truncatula and L. japonicus fit this amino acid profile (Supplementary Table S4). The CLE domain represents the functional peptide ligand, which is post-translationally cleaved and modified to 13 amino acids in AtCLV3 and LjCLE-RS14–6,35. A total of 66% (L. japonicus) and 61% (M. truncatula) of the prepropeptides have an amino acid at the 13th residue, with the remaining having a stop codon at position 13, and thus being only 12 amino acids long. In both species, the amino acid most commonly found at position 13 is arginine (Figs 1 and 2, Supplementary Fig. S4).

An arginine residue is found at the start of 83% of L. japonicus and 87% of M. truncatula CLE domains. Although less common, a number of CLE domains also begin with a histidine, and this is conserved between orthologues of different species. Three of the four peptides beginning with a histidine in A. thaliana are Tracheary Differentiation Inhibitory Factors (TDIF) that are involved in vascular differentiation36. L. japonicus and M. truncatula each have three CLE peptides beginning with a histidine (LjCLE26, LjCLE29 and LjCLE31, and MtCLE05, MtCLE06 and MtCLE37) that appear orthologous to the TDIF factors. However, they do not appear to have an orthologue of the functionally unrelated fourth CLE peptide of Arabidopsis to begin with a histidine, AtCLE46, and its putative soybean orthologue, GmCLE133.

The most highly conserved CLE domain residues of M. truncatula are arginine at position one, glycine at position six and histidine at position 11, with all three present in 87% of the peptides (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the most conserved CLE domain residue of L. japonicus is histidine at position 11 (91%), with only three sequences having a serine at this position and one sequence having a glutamine (Fig. 2). Residues 1, 4, 6, 7, 9 and 11 are also highly conserved (>82%) in the CLE domain of both species (Figs 1 and 2, Supplementary Fig. S4). These residues are all considered critical for function except for the proline at position nine37.

Outside of the CLE domain there is little conservation within the L. japonicus and M. truncatula CLE prepropeptide families (Figs 1 and 2). However, the signal peptide, which is predicted to either export the entire prepropeptide or the cleaved propeptide outside of the cell1,38, contains a typical hydrophobic motif consisting of predominantly leucine and isoleucine (Figs 1 and 2). The size of the predicted signal peptide ranges from 19 to 43 residues (Table 1). Additionally, the truncated LjCLE5 prepropeptide has a predicted signal peptide cleavage site between residues 14 and 15 (Table 1).

Hastwell et al.3 classified the CLE prepropeptides of soybean and common bean into seven distinct Groups (I to VII). The prepropeptides within each group show sequence conservation within and outside of the CLE domain. Based on the phylogenetic tree of the prepropeptides in L. japonicus, M. truncatula, A. thaliana and P. vulgaris, these groups remain conserved (Supplementary Fig. S3, Supplementary Table S5). This is especially evident with the Group VI CLE prepropeptides, which function in nodulation regulation, and Group III CLE prepropeptides, which show high sequence conservation with the Arabidopsis TDIF peptides, AtCLE41, AtCLE42 and AtCLE44 (Supplementary Fig. S3, Supplementary Table S5).

Identification of CLE40

A well characterised peptide, AtCLE40, has been shown to act as the root paralogue of AtCLV3 to regulate the stem cell population of the root apical meristem16–18. Putative orthologues of AtCLE40 have been identified in M. truncatula, P. vulgaris and G. max (MtCLE39, PvCLE40, GmCLE40a and GmCLE40b 3). Interestingly, our BLAST searches using the L. japonicus genome failed to identify a CLE40 orthologue. However, a region on chromosome 3 (chr3:40213173..40213683) exhibits a very high level of sequence similarity to these CLE40 orthologues, in addition to having a similar genomic environment to them (Fig. 6). All previously identified CLV3 and CLE40 orthologues contain two introns. The putative L. japonicus CLE40 orthologue, identified here as LjCLE48, contains conserved predicted intron boundaries for the second intron, which correspond to the CLE40 orthologues, but there are no predicted boundary sites for the first intron. Given this critical change at the 5′ end of LjCLE48, it appears unlikely that the resulting prepropeptide would produce a functional peptide product. This may suggest that another CLE peptide has evolved to perform the function of CLE40 in L. japonicus.

Nodulation CLE peptides

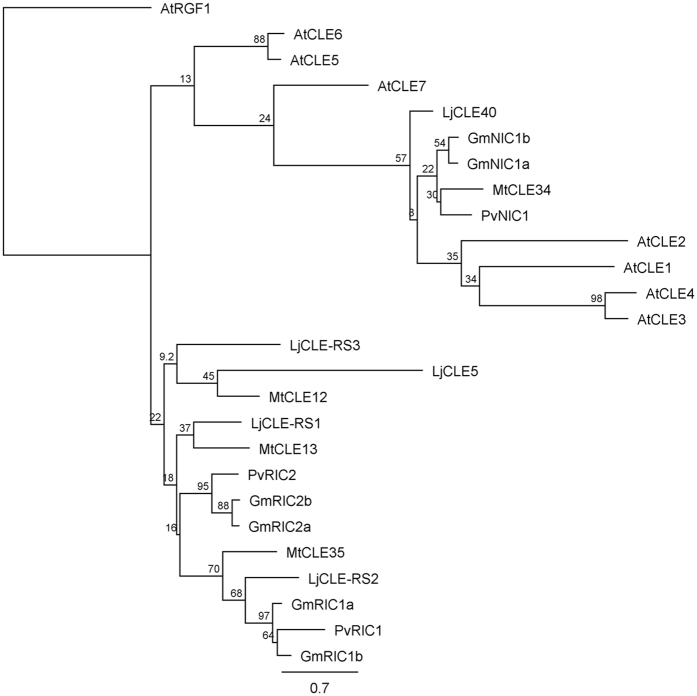

CLE genes in Group VI of soybean and common bean are known to respond to symbiotic bacteria, collectively called rhizobia, and act to control legume nodulation. The rhizobia-induced nodulation-suppressing CLE peptide encoding genes of L. japonicus and M. truncatula, known as LjCLE-RS1, LjCLE-RS2, LjCLE-RS3, MtCLE12 and MtCLE1327–29,39,40, cluster with these Group VI members of soybean and common bean3. Interestingly, two additional CLE prepropeptides of unknown function, called MtCLE35 and LjCLE5, also group closely (Supplementary Fig. S3). Okamoto et al.27 noted that LjCLE5 did not have a predicted signal peptide and that no expression could be detected. However, upstream of the previously predicted LjCLE5 start codon is another possible methionine (Fig. 5). The sequence following this alternative start codon corresponds closely with that of MtCLE12 (71.1% similarity), but the translation would result in a truncated protein prior to the CLE domain. Signal peptide prediction using SignalP (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) suggests that there is a possible cleavage site at position 30 of the longer (but non-functional) LjCLE5. Interestingly, MtCLE35 contains the consensus sequence TLQAR, which is consistent with the nodulation-suppressing CLE peptides, whereas LjCLE5 does not. The functional analysis of MtCLE35 would be of great interest to the nodulation field.

In addition to having rhizobia-induced CLE peptides, soybean has an additional nitrate-induced CLE peptide, GmNIC1a, which acts locally to supress nodulation39. To date, no orthologue of GmNIC1a has been reported in L. japonicus or M. truncatula. Here, we used GmNIC1a and a BLAST search of the L. japonicus and M. truncatula genomes to reveal likely orthologous candidates (Supplementary Fig. S3). In soybean and common bean, NIC1 and RIC1 are located tandemly within the genome39,40. In L. japonicus, the putative NIC1 and RIC1 orthologues (LjCLE40 and LjCLE-RS2, respectively) appear in tandem with LjCLE-RS3 and are approximately 24 kb apart on chromosome 3. Interestingly, LjCLE40 was also recently found to be induced by rhizobia inoculation29. In M. truncatula, the predicted orthologue of NIC1 is MtCLE34, which is located tandemly on chromosome 2 with MtCLE35. However, a C > T mutation at base 148 of MtCLE34 results in a premature stop codon and thus the translated product of this gene is likely non-functional. Further investigations are required to determine if the product is indeed truncated.

The legume nodulation CLE peptides are most similar to AtCLE1-7 of A. thaliana, however no direct orthologues have been identified as A. thaliana lacks the ability to form a symbiotic relationship with rhizobia or arbuscular mycorrhizae2. A targeted phylogenetic analysis was utilised here to investigate whether there are specific A. thaliana CLE peptides within AtCLE1-7 that are more closely linked with the nodulation CLE peptides of M. truncatula, L. japonicus, P. vulgaris and G. max (Fig. 7). As expected, the rhizobia-induced CLE peptides form a distinct branch from the nitrate-induced CLE peptides of legumes, and not surprisingly, the A. thaliana CLE peptides AtCLE1-7 group closer to these nitrate-induced sequences. This finding further supports the distinction of Group VI made by Hastwell et al. (2015).

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree of known legume nitrate-induced CLE peptides, rhizobia-induced CLE peptides, including two likely orthologous identified here in addition to Arabidopsis thaliana AtCLE1-7, which are most similar to these legume-specific CLE peptides. Bootstrap confidence values displayed are expressed as a percentage of 1,000 bootstrap replications, using AtRGF1 as an outgroup.

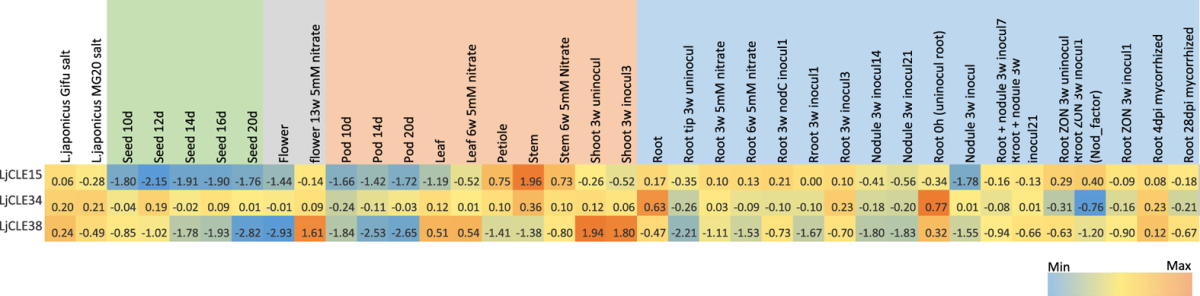

Expression of CLE peptide-encoding genes of M. truncatula and L. japonicus

It would be of little biological relevance to apply the peptides identified here to plants without first understanding their structural modifications and location of synthesis. We therefore used an in-silico approach to further assist in the functional characterisation of these genes. Publicly available transcriptome databases of M. truncatula and L. japonicus were used to collect expression data of the CLE peptide-encoding genes. A meta-analysis was performed to determine if putative orthologues identified by sequence characterisation and phylogenetic analyses exhibited similar expression patterns (Tables 2 and 3). Some similarity was seen between the putative orthologues, but the number of currently annotated CLE-peptide encoding genes limited a more detailed analysis.

Table 2.

Normalised Medicago truncatula CLE peptide-encoding gene expression displayed as log2-transformed values (5.75 = 54.1 fold). The colour scale is independent for each gene.

Table 3.

Normalised Lotus japonicus CLE peptide-encoding gene expression displayed as displayed as log2-transformed values (1.96 = 3.9 fold). The colour scale is independent for each gene.

A number of putative orthologues identified in the phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. S3) showed similar expression trends across tissues, such as PvCLE25 3 and MtCLE08, which were both expressed in the root, nodules and stem (Table 2). LjCLE15 is expressed highest in the stem with lower expression levels found across all other tissue types and genes that group closely, MtCLE18 and PvCLE24, are expressed in both the stem and root, whereas AtCLE12, which also groups closely is only found in the root (Tables 2 and 3). MtCLE17 shares a similar expression pattern to PvCLE23, GmCLE23a and GmCLE23b 3, being expressed across all tissue types except in seeds, with MtCLE17 also having notable higher expression in flowers than that of its putative orthologues, which shows little expression in the flower tissue (Table 2). MtCLE12 and MtCLE13 are currently the only functionally characterised M. truncatula CLE peptide-encoding genes, and the transcriptomic data for both genes is consistent with the literature28, being expressed in the nodules at different stages of development.

In contrast, some CLE peptide-encoding gene orthologues did not exhibit similar expression patterns within the transcriptomes according to the tissues and treatments available. PvTDIF1, GmTDIF1a and GmTDIF1b show high levels of expression across the different tissues3, with high root expression being of particular importance, as it is the only TDIF peptide-encoding gene to exhibit expression in the root. Their putative orthologues, AtCLE41 and AtCLE44 are also expressed in the root, in addition to other tissue types tested3, and M. truncatula orthologue, MtCLE06, shows no expression in the seeds and is only lowly expressed in the root. PvCLE29 was noted by Hastwell et al.3 to have very high expression only in the flower. The putative orthologue LjCLE19, has previously been shown to respond in the root to phosphate treatment30 and more recently mycorrhizae colonization31, which is also not consistent with the expression of PvCLE29 3.

Discussion

The importance of peptides in plant development is becoming increasingly evident with an extensive number of peptides and peptide families being discovered1. CLE peptides are no exception, with confirmed roles in meristematic tissue maintenance, and abiotic and biotic responses; however, the precise function of most is yet to be elucidated. To assist in the discovery of novel CLE peptide functions, the entire CLE peptide family of two model legumes, M. truncatula and L. japonicus, was identified here. Our analyses increased the number of annotated CLE peptides from 24 to 52 in M. truncatula and from 44 to 53 in L. japonicus. These were subjected to a range of comparative bioinformatics analyses to create a resource that can be utilised for further reverse-genetics-based functional characterisation. Additionally, six multi CLE domain-encoding genes and a number of pseudogenes were identified across the two species.

The phylogenetic analysis conducted using entire families of CLE prepropeptides of M. truncatula, L. japonicus, A. thaliana and P. vulgaris shows strong groupings between those having a similar CLE domain and a known or predicted function. The gene clusters identified here are generally conserved with those identified by Hastwell et al.3, which were divided into seven groups (Group I – VII).

M. truncatula and L. japonicus have a similar sized genome (500 Mbp) and share a common ancestor ~37-38 MYA, which is more recent than their shared ancestry with P. vulgaris (~45-59 MYA)41. The number of CLE peptide-encoding genes present (52 and 53 respectively), is consistent with the number in the P. vulgaris genome, 46, and is roughly half that of G. max, which has 843 due to a more recent (~13 MYA) whole genome duplication event42.

The number of CLE peptide-encoding genes in the legumes is higher than that of A. thaliana, which has 32. This is predominately due to the absence of CLE peptide-encoding genes involved in symbioses between rhizobia (Group VI) or mycorrhizae3,31,43. The symbioses formed by legumes enable them to acquire nutrients that would otherwise be unavailable44,45. Nodulation control pathways are well characterised in M. truncatula and L. japonicus, beginning with the production of a CLE peptide2,19,46. However, a separate nitrate-regulated nodulation pathway identified in G. max has not yet been established in these two species. Here, a putative orthologue of GmNIC1 and PvNIC1, which responds to the level of nitrate in the rhizosphere to inhibit nodulation2,39,40, has been identified in M. truncatula. However, MtCLE34 is likely to be non-functional as a result of a truncation before the CLE domain. The putative orthologue in L. japonicus, LjCLE5, which has not yet been detected in gene expression studies, is likely to be non-functional as a result of a naturally-occurring insertion/deletion mutation. Further analysis is also needed to determine if MtCLE35 has a functional role in nodulation and if another gene in L. japonicus has gained the ability to regulate nodulation in response to nitrogen. Indeed, the latter is hinted towards by the ability of LjLCE-RS1 to be induced by both rhizobia and nitrate to control nodule numbers2,27.

Although A. thaliana does not enter into a symbiosis with either rhizobia or mycorrhizae, its genome contains orthologues to known symbiosis genes, such as AtPOLLUX 47. However, our work indicates that no CLE peptide-encoding genes have yet been identified that show homology or synteny to the rhizobia-induced CLE peptides. It would be of interest to determine if such CLE peptide encoding genes previously existed, or exist but have been overlooked in A. thaliana due to being highly divergent from the symbiosis CLE peptides in legumes and other species.

Recent advances in genome sequencing, bioinformatics resources and the identification of entire CLE peptide families of soybean, common bean and Arabidopsis, have been utilised to capture the entire CLE peptide-encoding gene families of two important model legume species, M. truncatula and L. japonicus. Further characterisation of these CLE peptide-encoding genes revealed orthologues amongst the species, many of which appear functional, with some likely to be pseudogenes. The identification and genetic characterisation of these genes will benefit future studies aimed at functionally characterising these integral molecular components of plant meristem formation and maintenance.

Methods

Gene Identification

Candidate CLE peptide-encoding genes were identified in L. japonicus and M. truncatula using TBLASTN searches with known all CLE prepropeptides of G. max 3, P. vulgaris 3 and A. thaliana 48. The M. truncatula Mt4.0v1 genome was searched in Phytozome (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/)49,50 and the L. japonicus v3.0 genome was searched in Lotus Base (https://lotus.au.dk/). Initial searches were conducted with E-value = 10. The results were manually validated for the presence of a CLE peptide-encoding gene in an open reading frame. Orthologues were also identified using TBLASTN of newly identified CLE prepropeptide sequences where clear orthologous were not identified between M. truncatula and L. japonicus, using E-value = 1.

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) were generated for M. truncatula and L. japonicus CLEs individually, using all full length prepropeptide sequences as input into HMMER3, respectively (www.hmmer.org). Next, based on the generated HMMs, jackHMMER (www.hmmer.org) was applied to iteratively search for CLE sequences in M. truncatula and L. japonicus protein databases using a bit score of 50.

Phylogenetic analysis

Multiple sequence alignments were constructed as outlined in Hastwell et al.3. Manual adjustments were made to some predicted sequences, particularly in regards to their start codon, based on similarity to duplicate genes, clustering genes, and/or likely orthologous genes. Multiple sequence alignments constructed without truncated or likely non-functional CLE prepropeptides were used to generate phylogenetic trees. The trees were constructed using methods described in Hastwell et al.3 using 1,000 bootstrap replications in all cases, except for the tree constructed using the entire families of L. japonicus, M. truncatula, A. thaliana and P. vulgaris CLE peptides, which used 100 bootstrap replications. Where orthologues were not apparent, the genomes of L. japonicus and M. truncatula were re-searched in an attempt to identify a possible orthologue.

Sequence Characterisation

The presence of a signal peptide encoding domain and putative signal peptide cleavage site of the CLE prepropeptides was identified using SignalP (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP /)51. If no signal peptide was detected, the sequence was manually examined for an up- or downstream methionine, which could be the likely start codon. The modified sequence was re-entered into SignalP and a signal peptide was detected in most instances. Possible intron boundary sites were identified using the NetPlantGene Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetPGene/)52,53 and the nucleotide splice sites and resulting prepropeptides were compared with orthologous sequences. Sequence logo graphs of the CLE domain were generated using multiple sequence alignments in Geneious Pro v10.0.253.

Genomic environments were established using five up- and down-stream annotated genes in Phytozome and Lotus Base (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/; https://lotus.au.dk/)49,50. Orthologues of individual genes within the genomic environment lacking functional family annotations were identified using BLAST within and between the two databases.

M. truncatula and L. japonicus transcriptome meta-analysis

The meta-analysis of the normalised transcriptome data was done using publicly available data sets located on the Medicago eFP browser (http://bar.utoronto.ca/efpmedicago/)49,54,55 and the Medicago truncatula Gene Expression Atlas (http://mtgea.noble.org/v3/)54,56 for M. truncatula, and The Lotus japonicus Gene Expression Atlas (http://ljgea.noble.org/v2/)57 for L. japonicus.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Hermon Slade Foundation, and Australian Research Council Discovery Project grants (DP130103084 and DP130102266). The Fellowship Fund Inc. is also thanked for provision of a Molly-Budtz Olsen PhD Fellowship to AHH. TCDB was funded by the European Research Council via a Global Postdoc Fellowship under the Horizon 2020 Marie Sklodowska-Curie Action (Grant no. 659251). We would also like to thank Wolf R. Scheible and Michael K. Udvardi at the Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation, OK, USA for their assistance with the study.

Author Contributions

A.H.H., B.J.F. and P.M.G. designed the study. A.H.H. and T.C.dB. collected the data, A.H.H., T.C.dB. and B.J.F. interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript, and. A.H.H. and B.J.F. prepared the figures and tables. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14991-9.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09296-w

Change History: A correction to this article has been published and is linked from the HTML version of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tavormina P, De Coninck B, Nikonorova N, De Smet I, Cammue BPA. The Plant Peptidome: An Expanding Repertoire of Structural Features and Biological Functions. The Plant Cell. 2015;27:2095–2118. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hastwell AH, Gresshoff PM, Ferguson BJ. The structure and activity of nodulation-suppressing CLE peptide hormones of legumes. Functional Plant Biology. 2015;42:229–238. doi: 10.1071/FP14222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hastwell AH, Gresshoff PM, Ferguson BJ. Genome-wide annotation and characterization of CLAVATA/ESR (CLE) peptide hormones of soybean (Glycine max) and common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), and their orthologues of Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2015;66(17):5271–5287. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohyama K, Shinohara H, Ogawa-Ohnishi M, Matsubayashi Y. A glycopeptide regulating stem cell fate in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Chemical Biology. 2009;5:578–580. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamoto S, Shinohara H, Mori T, Matsubayashi Y, Kawaguchi M. Root-derived CLE glycopeptides control nodulation by direct binding to HAR1 receptor kinase. Nature Communications. 2013;4:2191. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, et al. In planta processing and glycosylation of a nematode CLAVATA3/ENDOSPERM SURROUNDING REGION-like effector and its interaction with a host CLAVATA2-Like receptor to promote parasitism. Plant Physiology. 2015;167:262–272. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.251637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferguson BJ, Mathesius U. Phytohormone regulation of legume-rhizobia interactions. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2014;40:770–790. doi: 10.1007/s10886-014-0472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Endo S, Betsuyaku S, Fukuda H. Endogenous peptide ligand–receptor systems for diverse signalling networks in plants. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2014;21:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsen AN, Skriver K. Ligand mimicry? Plant-parasitic nematode polypeptide with similarity to CLAVATA3. Trends in Plant Science. 2003;8:55–7. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Replogle A, et al. Nematode CLE signalling in Arabidopsis requires CLAVATA2 and CORYNE. The Plant Journal. 2011;65:430–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaillochet C, Lohmann JU. The never-ending story: from pluripotency to plant developmental plasticity. Development. 2015;142:2237–2249. doi: 10.1242/dev.117614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greb T, Lohmann JU. Plant Stem Cells. Current biology. 2016;26(17):R816. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM. CLAVATA3 is a specific regulator of shoot and floral meristem development affecting the same processes as CLAVATA1. Development. 1995;121(7):2057–67. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaillochet C, Daum G, Lohmann JU. O Cell, Where Art Thou? The mechanisms of shoot meristem patterning. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2015;23:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Somssich M, Je BI, Simon R, Jackson D. CLAVATA-WUSCHEL signaling in the shoot meristem. Development. 2016;143(18):3238–3248. doi: 10.1242/dev.133645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hobe M, Müller R, Grünewald M, Brand U, Simon R. Loss of CLE40, a protein functionally equivalent to the stem cell restricting signal CLV3, enhances root waving in Arabidopsis. Development Genes and Evolution. 2003;213:371–381. doi: 10.1007/s00427-003-0329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma V, Ramirez J, Fletcher J. The Arabidopsis CLV3-like (CLE) genes are expressed in diverse tissues and encode secreted proteins. Plant Molecular Biology. 2003;51:415–425. doi: 10.1023/A:1022038932376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berckmans B, Simon R. A feed-forward regulation sets cell fates in roots. Trends in Plant Science. 2016;21:373–375. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid DE, Ferguson BJ, Hayashi S, Lin Y-H, Gresshoff PM. Molecular mechanisms controlling legume autoregulation of nodulation. Annals of Botany. 2011;108:789–795. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sawa S, Kinoshita A, Nakanomyo I, Fukuda H. CLV3/ESR-related (CLE) peptides as intercellular signalling molecules in plants. The Chemical Record. 2006;6:303–310. doi: 10.1002/tcr.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito Y, et al. Dodeca-CLE peptides as suppressors of plant stem cell differentiation. Science. 2006;313:842–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1128436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirakawa Y, Kondo Y, Fukuda H. TDIF peptide signalling regulates vascular stem cell proliferation via the WOX4 homeobox gene in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2010;22:2618–2629. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.076083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Etchells JP, Smit ME, Gaudinier A, Williams CJ, Brady SM. A brief history of the TDIF‐PXY signalling module: balancing meristem identity and differentiation during vascular development. New Phytologist. 2016;209(2):474–84. doi: 10.1111/nph.13642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Rybel B, Mähönen AP, Helariutta Y, Weijers D. Plant vascular development: from early specification to differentiation. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2016;17(1):30–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2015.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchum MG, et al. Nematode effector proteins: an emerging paradigm of parasitism. New Phytologist. 2013;199:879–894. doi: 10.1111/nph.12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verdier J, et al. Establishment of the Lotus japonicus Gene Expression Atlas (LjGEA) and its use to explore legume seed maturation. Plant Journal. 2013;74:351–62. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okamoto S, et al. Nod Factor/nitrate-induced CLE genes that drive HAR1-mediated systemic regulation of nodulation. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2009;50:67–77. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mortier V, et al. CLE peptides control Medicago truncatula nodulation locally and systemically. Plant Physiology. 2010;153:222–237. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.153718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishida H, Handa Y, Tanaka S, Suzaki T, Kawaguchi M. Expression of the CLE-RS3 gene suppresses root nodulation in Lotus japonicus. Journal of plant research. 2016;129(5):909–19. doi: 10.1007/s10265-016-0842-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Funayama-Noguchi S, Noguchi K, Yoshida C, Kawaguchi M. Two CLE genes are induced by phosphate in roots of Lotus japonicus. Journal of Plant Research. 2011;124:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s10265-010-0342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Handa Y, et al. RNA-seq Transcriptional Profiling of an Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Provides Insights into Regulated and Coordinated Gene Expression in Lotus japonicus and Rhizophagus irregularis. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2015;56(8):1490–1511. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcv071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen SK, et al. The association of homeobox gene expression with stem cell formation and morphogenesis in cultured Medicago truncatula. Planta. 2009;230:827–840. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-0988-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamoto S, Nakagawa T, Kawaguchi M. Expression and functional analysis of a clv3-like gene in the model legume Lotus japonicus. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2011;52:1211–1221. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meng L, Buchanan BB, Feldman LJ, Luan S. CLE-like (CLEL) peptides control the pattern of root growth and lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109(5):1760–1765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119864109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shinohara H, Moriyama Y, Ohyama K, Matsubayashi Y. Biochemical mapping of a ligand‐binding domain within Arabidopsis BAM1 reveals diversified ligand recognition mechanisms of plant LRR‐RKs. The Plant Journal. 2012;70(5):845–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.04934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grienenberger E, Fletcher JC. Polypeptide signaling molecules in plant development. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2015;23:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reid DE, Li D, Ferguson BJ, Gresshoff PM. Structure–function analysis of the GmRIC1 signal peptide and CLE domain required for nodulation control in soybean. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2013;64:1575–1585. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim CW, Lee YW, Hwang CH. Soybean nodule-enhanced CLE peptides in roots act as signals in GmNARK-mediated nodulation suppression. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2011;52(9):1613–1627. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reid DE, Ferguson BJ, Gresshoff PM. Inoculation- and nitrate-induced CLE peptides of soybean control NARK-dependent nodule formation. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2011;24:606–618. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-10-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferguson BJ, et al. The soybean (Glycine max) nodulation-suppressive CLE peptide, GmRIC1, functions interspecifically in common white bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), but not in a supernodulating line mutated in the receptor PvNARK. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2014;12:1085–1097. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi HK, et al. Estimating genome conservation between crop and model legume species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:15289–15294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402251101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmutz J, et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463(7278):178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Delaux P, et al. Comparative phylogenomics uncovers the impact of symbiotic associations on host genome evolution. PLoS Genetics. 2014;10(7):e1004487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith FA, Smith SE. What is the significance of the arbuscular mycorrhizal colonisation of many economically important crop plants? Plant and Soil. 2011;348(1-2):63–79. doi: 10.1007/s11104-011-0865-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gresshoff PM, et al. The value of biodiversity in legume symbiotic nitrogen fixation and nodulation for biofuel and food production. Journal of plant physiology. 2015;172:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferguson BJ, et al. Molecular analysis of legume nodule development and autoregulation. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2010;52(1):61–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delaux PM, Séjalon-Delmas N, Bécard G, Ané JM. Evolution of the plant–microbe symbiotic ‘toolkit’. Trends in plant science. 2013;18(6):298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cock JM, McCormick S. A large family of genes that share homology with CLAVATA3. Plant Physiology. 2001;126:939–942. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.3.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young ND, et al. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature. 2011;480(7378):520–4. doi: 10.1038/nature10625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodstein D, et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40(D1):D1178–D1186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petersen TN, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nature Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hebsgaard SM, et al. Splice site prediction in Arabidopsis thaliana DNA by combining local and global sequence information. Nucleic Acids Research. 1996;24(17):3439–3452. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.17.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kearse M, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benedito VA, et al. A gene expression atlas of the model legume Medicago truncatula. The Plant Journal. 2008;55:504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Righetti K, et al. Inference of longevity-related genes from a robust coexpression network of seed maturation identifies regulators linking seed storability to biotic defense-related pathways. The plant cell. 2015;27(10):2692–2708. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He J, et al. The Medicago truncatula gene expression atlas web server. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:441. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verdier J, et al. Establishment of the Lotus japonicus Gene Expression Atlas (LjGEA) and its use to explore legume seed maturation. The Plant Journal. 2013;74(2):351–362. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.