Abstract

For the concept of aromaticity, energetic quantification is crucial. However, this has been elusive for excited-state (Baird) aromaticity. Here we report our serendipitous discovery of two nonplanar thiophene-fused chiral [4n]annulenes Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw, which by computational analysis turned out to be a pair of molecules suitable for energetic quantification of Baird aromaticity. Their enantiomers were separable chromatographically but racemized thermally, enabling investigation of the ring inversion kinetics. In contrast to Th6 CDH Screw, which inverts through a nonplanar transition state, the inversion of Th4 COT Saddle, progressing through a planar transition state, was remarkably accelerated upon photoexcitation. As predicted by Baird’s theory, the planar conformation of Th4 COT Saddle is stabilized in the photoexcited state, thereby enabling lower activation enthalpy than that in the ground state. The lowering of the activation enthalpy, i.e., the energetic impact of excited-state aromaticity, was quantified experimentally to be as high as 21–22 kcal mol–1.

Baird’s rule applies to cyclic π-conjugated molecules in their excited state, yet a quantification of the involved energetics is elusive. Here, the authors show the ring inversion kinetics of two nonplanar and chiral [4n]annulenes to support Baird’s rule from an energetic point of view.

Introduction

Annulenes are monocyclic hydrocarbons comprising alternating single and double bonds, whose preferred conformations in the electronic ground (S0) state are determined by the number of their π-electrons1. Annulenes with 4n + 2 π-electrons are categorized as Hückel aromatic compounds that prefer to adopt a bond-length equalized planar conformation because the electronic conjugation enabled by planarization leads to energetic stabilization2, 3. In contrast, annulenes with 4n π-electrons are categorized as Hückel antiaromatic compounds that tend to adopt a bond-length alternate nonplanar conformation because of their unfavorable electronic conjugation and/or increased ring strain4–8. In 1972, Baird theoretically deduced9 that [4n]annulenes in the triplet excited (T1) state, just like [4n + 2]annulenes in the S0 state, prefer to adopt a planar conformation because the resulting electronic conjugation leads to energetic stabilization10, 11. Later, Baird’s theory was shown computationally to be also applicable to the singlet excited (S1) state12–14. Indeed, a series of photochemical and photophysical phenomena that cannot be explained by Hückel’s rule have been reasonably explained by Baird’s rule15, 16. For example, Wan et al. utilized the concept of excited-state aromaticity to explain why certain SN1-type substitution reactions involving cyclic intermediates with 4n π-electrons are facilitated by photoirradiation17–20. Ottosson, Kilså, and coworkers21, 22 showed that Baird’s rule can account for how the excitation energy of fulvene changes with its substituents. Indeed, Ottosson, and coworkers23 postulated that Baird’s theory is a useful back-of-an-envelope tool for the design and exploration of novel photofunctional materials, and also showed that it can be used to develop new photoreactions24, 25. As a seminal achievement to elucidate Baird’s rule, Kim, Osuka, and coworkers recently provided spectroscopic evidence of Baird aromaticity based on the transient absorption spectral profiles of a particular type of expanded porphyrin derivative26–28. Equally important for experimentally substantiating Baird’s rule is to energetically quantify the concept of excited-state aromaticity6. However, this essential issue has not been addressed because annulene derivatives that fulfill certain prerequisites are currently unavailable.

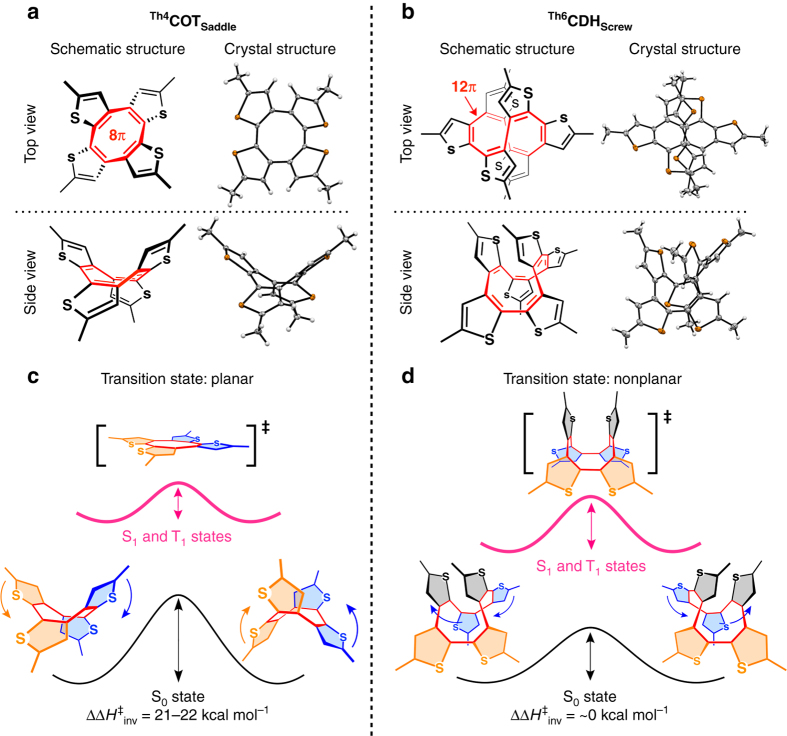

In the course of our study on the synthesis of thiophene oligomers using a modified Ullmann coupling reaction, we noticed two different chiral [4n]annulene derivatives as by-products: Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw. Single-crystal X-ray crystallographic analysis revealed that these by-products are nonplanar and conformationally chiral. We succeeded in their optical resolution using high-performance liquid chromatography on a chiral stationary phase (chiral HPLC). Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy in methylcyclohexane showed that the enantiomers of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw are racemized through ring inversion under appropriate conditions. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicated that Th4 COT Saddle adopts a planar conformation, whereas Th6 CDH Screw adopts a nonplanar conformation, in the transition state of their ring inversion processes. Of particular importance, we found that the racemization of Th4 COT Saddle is remarkably accelerated by its photoexcitation, whereas that of Th6 CDH Screw is unaffected by photoexcitation. We wondered whether these contrasting results are related to a prime issue of excited-state aromaticity, i.e., Baird aromaticity. In fact, quantum chemical computational analysis revealed that Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw are a pair of molecules suitable for energetic quantification of Baird aromaticity. Previous studies demonstrated experimentally that cyclooctatetraene (COT), oxepin, and thiepin analogs in the photoexcited state adopt planar conformations29, 30. However, they are planarized only in a barrierless manner, precluding energetic quantification of photoexcited planar [4n]annulenes. On the other hand, Th4 COT Saddle in the present study provides a sterically congested ring inversion process with a positive activation enthalpy. Because the transition state of the ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle involves its planarized core, the kinetic studies both in the S0 state and photoexcited (S1/T1) state surely enable us to support Baird’s rule from an energetic viewpoint.

Results

Synthesis and optical resolution of Th4COTSaddle and Th6CDHScrew

A β-linked thiophene dimer (Th2) was subjected to a modified Ullmann coupling reaction, and the crude reaction mixture was passed through a silica gel short column and submitted to size exclusion chromatography on a polystyrene gel column for the isolation of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw (Supplementary Methods). Th4 COT Saddle carries a COT ([8]annulene) core31, 32, while Th6 CDH Screw bears a cyclododecahexaene (CDH: [12]annulene) core33. Through vapor diffusion, all these annulenes afforded single crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography (Fig. 1a, b). The crystal structure of Th4 COT Saddle adopts a highly nonplanar conformation in its annulene core with a bond-length alternation. A similar structural feature was observed for the crystal of Th6 CDH Screw. Chiral HPLC (Supplementary Methods) was used to separate these chiral compounds into the corresponding enantiomers (Fig. 2e, f). Their enantiomers were thermally racemizable, which encouraged us to investigate the ring inversion kinetics. The enantiomers of Th4 COT Saddle, when heated above 40 °C in methylcyclohexane, underwent racemization (Fig. 3a), while those of Th6 CDH Screw were much more prone to racemization; the enantiomers of Th6 CDH Screw were racemized unless the compound was cooled below –40 °C (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 1.

[4n]Annulene derivatives with and without Baird aromaticity upon photoexcitation. a, b, Molecular structures and ORTEP drawings (50% ellipsoid probability) of Th4 COT Saddle (a) and Th6 CDH Screw (b), which have 8π-electron and 12π-electron annulene cores (red colored), respectively. c, d, Schematic illustrations of the energy barriers for the ring inversion events of Th4 COT Saddle (c) and Th6 CDH Screw (d), where colored arrows represent the movement directions of the thiophene rings of the same color. Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw invert through planar and nonplanar transition states, respectively, as shown in the square brackets. Black and pink-colored solid curves represent energy barriers in the ground and photoexcited states, respectively. Upon photoexcitation, the activation enthalpy for the ring inversion (∆H ‡ inv) of Th4 COT Saddle is lowered by 21–22 kcal mol–1, but that of Th6 CDH Screw remains unchanged

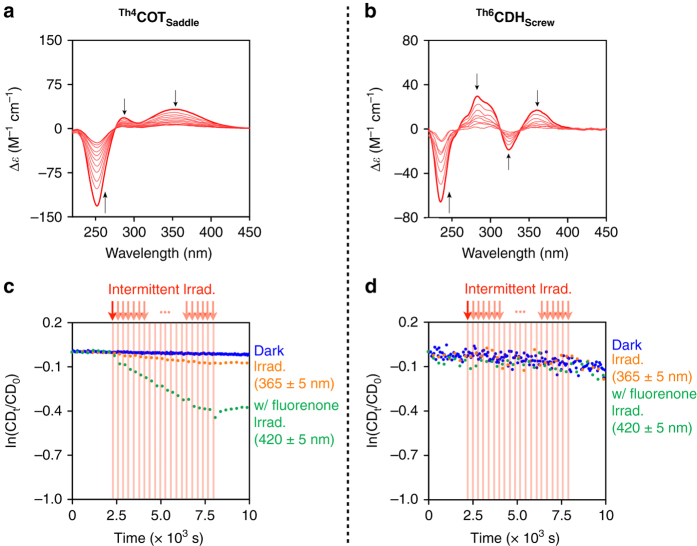

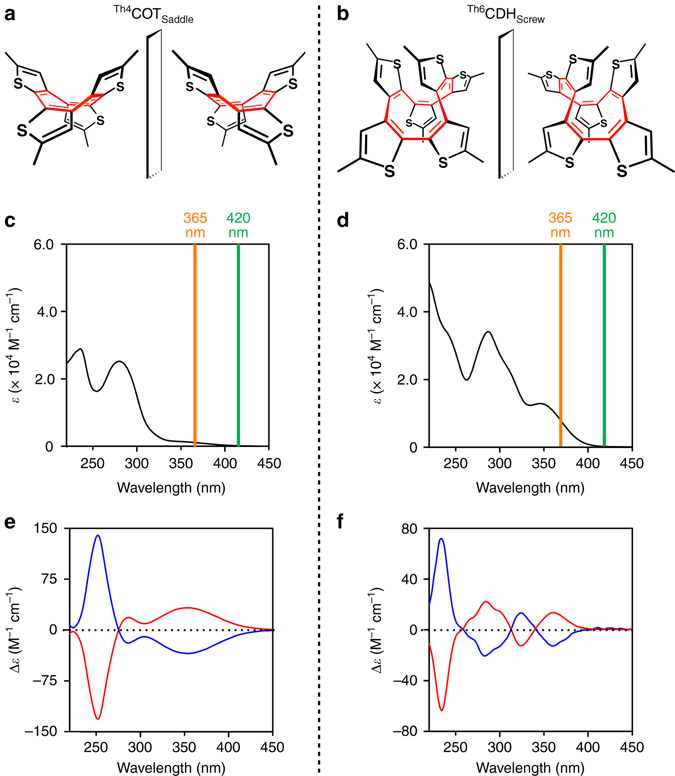

Fig. 2.

Optical features of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw. a, b, Schematic structures of the enantiomers of Th4 COT Saddle (a) and Th6 CDH Screw (b). c, d, Electronic absorption spectra of Th4 COT Saddle (c) and Th6 CDH Screw (d) in methylcyclohexane at 25 °C. Orange- and green-colored vertical lines correspond to the wavelengths of λ = 365 and 420 nm, which were utilized for direct and sensitized photoexcitation of the molecules, respectively. e, f, Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of Th4 COT Saddle (e) and Th6 CDH Screw (f) in methylcyclohexane at 25 and –20 °C, respectively. Blue- and red-colored traces represent the spectra of compounds obtained as the first and second fractions of the chiral HPLC, respectively

Fig. 3.

Ring inversion kinetics of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw. a, b, Time-dependent CD spectral change profiles (240-s interval) of Th4 COT Saddle (a) and Th6 CDH Screw (b) in methylcyclohexane at 60 and 0 °C, respectively. Black arrows in a and b represent the directions of the CD spectral change with time. c, d, Decay profiles of the CD intensities at 260 nm (c, Th4 COT Saddle) and 280 nm (d, Th6 CDH Screw) in deaerated methylcyclohexane at 20 and −20 °C, respectively. Blue-colored dots represent decay profiles without photoirradiation. Orange-colored dots represent decay profiles with photoirradiation (λ = 365 ± 5 nm). Green-colored dots represent decay profiles with photoirradiation (λ = 420 ± 5 nm) in the presence of fluorenone (0.34 equiv. for Th4 COT Saddle and 0.23 equiv. for Th6 CDH Screw). Photoirradiation (250 s, red vertical lines) and CD spectroscopy (50 s, white area between red vertical lines) were conducted alternately for 6000 s

Ring inversion in the electronic ground and excited states

The inversion kinetics of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw were studied in deaerated methylcyclohexane. Neither compound decomposed under photoexcitation (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). For the selective generation of the S1 state, Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw were photoexcited at their longest wavelength absorption bands (λ = 365 ± 5 nm, Fig. 2c, d). At 20 °C in the dark, the CD intensity of Th4 COT Saddle, as described above, remained unchanged over a period of 3 h (Fig. 3c, blue dots). However, when the solution was irradiated under otherwise identical conditions, the CD intensity gradually decreased (half-life (t 1/2) = 12 h) (Fig. 3c, orange dots). When the photoirradiation was stopped, the CD intensity no longer decreased. Transient absorption spectroscopy (TAS) of Th4 COT Saddle upon photoexcitation at λ = 355 nm enabled us to detect the S1 state dynamics, which decayed exponentially with a lifetime of 5.5 ps (Supplementary Fig. 16). No other excited species, including the T1 state, were detected. Hence, we conclude that the S1 state of Th4 COT Saddle can facilitate its ring inversion.

Because Baird aromaticity has typically been discussed in the T1 state9, 11, 34–36, it is important to confirm whether the ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle is facilitated in its triplet excited state. Therefore, we selectively generated the T1 state of Th4 COT Saddle by photoexcitation of fluorenone (0.34 equiv., E T = 50.9 kcal mol–1, φ T = 1.0037) at λ = 420 ± 5 nm as a triplet photosensitizer and investigated the ring inversion process of Th4 COT Saddle at 20 °C. Although Th4 COT Saddle does not absorb light in this wavelength region (ε = ~60 cm–1 M–1; Fig. 2c), the ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle was remarkably facilitated (t 1/2 = 2.1 h) by the photoexcitation of fluorenone (Fig. 3c, green dots, red-striped zone). Without photoirradiation, fluorenone itself did not facilitate the ring inversion (Fig. 3c, green dots, before and after red-striped zone). The triplet sensitization should occur smoothly, considering that the T1 state energy of Th4 COT Saddle is supposedly slightly lower than that of fluorenone (Supplementary Discussion). In fact, a photoexcited T1 species of Th4 COT Saddle with a lifetime of 2 µs was observed by TAS upon photoexcitation at λ = 420 nm in the presence of fluorenone (Supplementary Fig. 23). Just in case, when the system was bubbled with oxygen, a possible triplet quencher38, ring inversion was no longer facilitated by photoexcitation (Supplementary Fig. 11). These observations strongly support that the photo-accelerated ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle in the presence of fluorenone originates from its T1 state. As expected, the ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle in the S1 state was unaffected by O2 (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Baird’s rule explains why [4n]annulenes prefer to be planarized in their photoexcited states. As described in Fig. 4a, the ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle involves its planar transition state. In contrast, Th6 CDH Screw cannot be planarized during its ring inversion process (Fig. 4b). Does photoexcitation affect the ring inversion of Th6 CDH Screw? Compared with Th4 COT Saddle, Th6 CDH Screw is more prone to thermal ring inversion in the dark, and its enantiomers were racemized in methylcyclohexane, even at –20 °C (Fig. 3d, blue dots, t 1/2 = 18 h). Initially, a methylcyclohexane solution of Th6 CDH Screw at –20 °C was photoexcited at the longest wavelength absorption band (λ = 365 ± 5 nm). However, no acceleration was observed for its ring inversion. TAS of Th6 CDH Screw with photoexcitation at λ = 355 nm indicated the presence of both S1 and T1 states with lifetimes of 70 ps and 350 ns, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19). No accelerated ring inversion occurred when Th6 CDH Screw was placed under triplet sensitization conditions using photoexcited fluorenone (0.23 equiv.) at λ = 420 ± 5 nm. The contrasting results with planarizable Th4 COT Saddle and non-planarizable Th6 CDH Screw appear reasonable, if the observed phenomena are dominated by Baird’s rule. The possible effect of local heating (photothermal activation) on the accelerated ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle was excluded, as described in the Supplementary Discussion. All these observations indicate that kinetic analysis of the ring inversion events of photoexcited- and ground-state Th4 COT Saddle, when compared to those of Th6 CDH Screw, enable energetic quantification of Baird aromaticity.

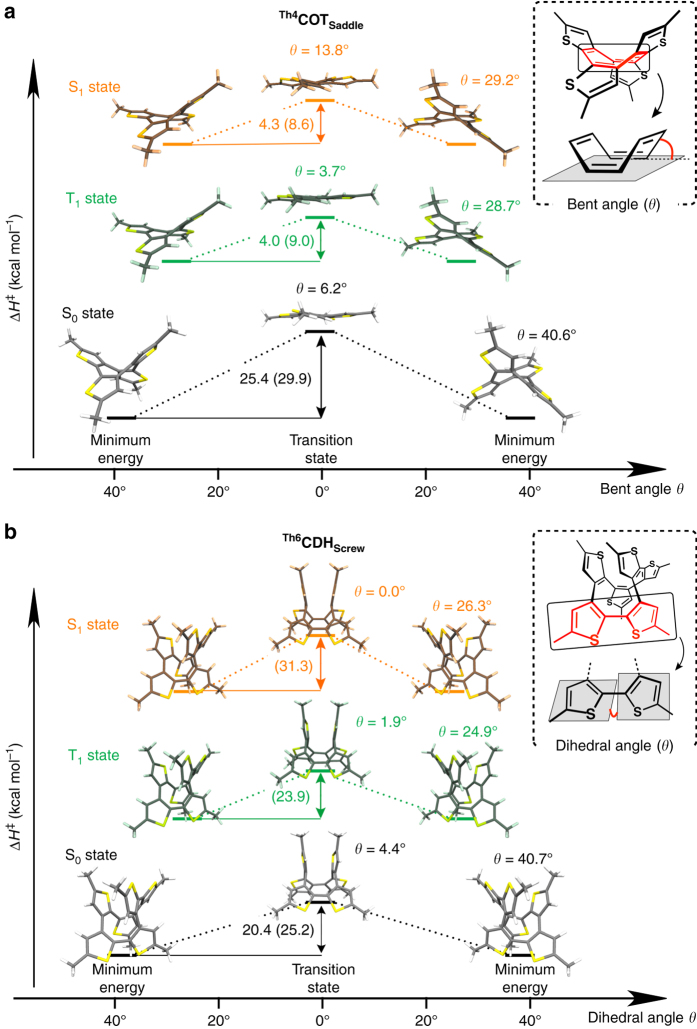

Fig. 4.

Ring inversion energetics of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw. a, Conformational change of Th4 COT Saddle calculated along the reaction coordinate. b, Conformational change of Th6 CDH Screw calculated along the reaction coordinate. Gray-, green- and orange-colored drawings represent the conformations in the S0, T1, and S1 states, respectively. For the S0 and T1 states, the structures were optimized at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6–31G(d) level, and the energy values were calculated by single-point calculations at the B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6–311+G(d,p) level using the optimized geometry. For the S1 state, the structures were optimized at the TD-B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6–31+G(d,p) level, and the energy values were obtained by the same level of calculation used for the structural optimization. Activation enthalpies experimentally obtained (computationally calculated) are given in kcal mol–1

Experimental evaluation of the activation enthalpies of ring inversion

We investigated the ring inversion processes of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw at varying temperatures in methylcyclohexane and analyzed their kinetic profiles using the Eyring equation (Supplementary Discussion). Based on the CD spectral decay profiles of Th4 COT Saddle at 40, 50, and 60 °C in the dark, the activation enthalpy of its ring inversion in the ground (S0) state was evaluated as 25.4 kcal mol–1 (Supplementary Fig. 13a, c). The decay profiles of Th4 COT Saddle at 0, 10, and 20 °C upon photoexcitation afforded activation enthalpies in the S1 and T1 states of 4.3 and 4.0 kcal mol–1, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). The calculated activation enthalpies at (TD-)B3LYP-D3(BJ) were 29.9, 8.6, and 9.0 kcal mol–1 for the S0, S1, and T1 states, respectively, which are in agreement with the experimental values. It is now clear that the planar transition state in the ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle is photochemically stabilized in the excited (S1/T1) states. In sharp contrast, as described in Fig. 3d, the inversion rate of Th6 CDH Screw is unaffected by photoexcitation; thus, the activation enthalpies in the photoexcited (S1/T1) states would not differ from that in the S0 state (20.4 kcal mol–1, Supplementary Fig. 13b, d). In other words, no photochemical stabilization occurs at the nonplanar transition state in the ring inversion of Th6 CDH Screw. This is supported by the calculated values at (TD-)B3LYP-D3(BJ) of 25.2, 31.3, and 23.9 kcal mol–1 for the S0, S1, and T1 states, respectively. The energetic quantification results are consistent with Baird’s rule.

Computational investigation of energetics and aromaticity

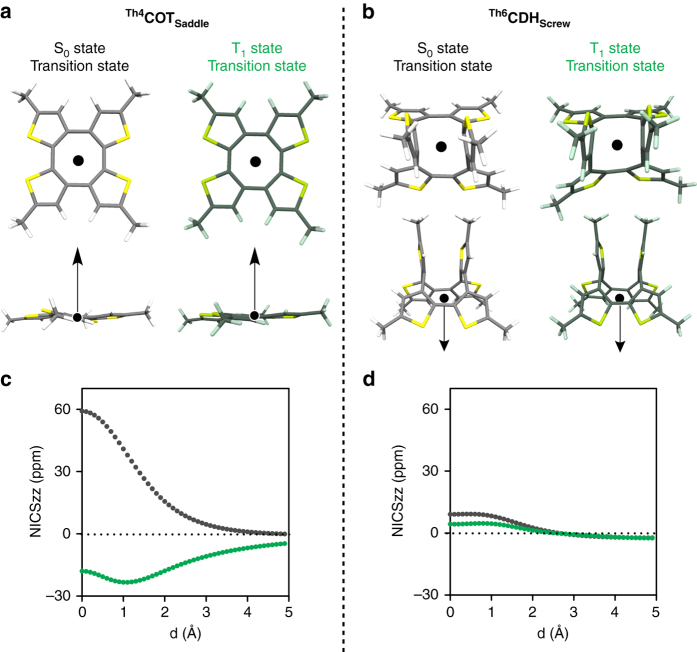

Quantum chemical calculations are essential to clarify whether our observations, involving photochemical planarization of [4n]annulenes, is indeed caused by Baird aromaticity. In [4n]annulenes with fused arene moieties, the excited state structure is in some cases explained by the emergence of Baird aromaticity in the excited state29, but there are also examples where the excited state is located to the arene fragment39. Therefore, we performed quantum chemical calculations of the ring inversion processes of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw in the S0, S1, and T1 states. The calculated transition state structures of Th4 COT Saddle in the S0, S1, and T1 states are quasi-planar, as indicated by the small bent angles (θ) of the COT core (θ = 6.2, 13.8, and 3.7° for the S0, S1, and T1 states, respectively; Fig. 4a). These geometries enable efficient pπ-orbital overlap, which is in line with observed 8π-electron conjugation, by means of molecular orbitals and spin densities, in the COT core (Supplementary Figs. 26 and 31). The alternation of C–C bond lengths in the COT core at the transition state in the S0 state and equalization of those in the photoexcited (S1/T1) states demonstrate the antiaromatic and aromatic natures of the transition states in the S0 state and photoexcited (S1/T1) states, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 40). Magnetic aromaticity indices40, such as anisotropy of the induced current density (ACID)40–42 and nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS)43–46, are commonly utilized to examine tentatively aromatic molecules. For the transition state structures in the S0 and T1 states, paratropic (counterclockwise, antiaromatic) and diatropic (clockwise, aromatic) ring currents, respectively, were observed in the ACID plots (Supplementary Figs. 34 and 36). The NICSzz scans, orthogonal to the central COT ring (Fig. 5a), also showed characteristic positive and negative minima for the transition states in the S0 and T1 states, respectively (Fig. 5c). On the other hand, the magnetic indices of aromaticity for the S1 state are harder to assess because ACID is not available and NICS is not well-established (Supplementary Discussion). The NICSzz scan, which was obtained with CASSCF(8in8)/6–31 + + G(d,p) using Dalton 2016.0 (Supplementary Methods) and should be taken as qualitative rather than quantitative, showed the characteristic aromatic minima at the transition state in the S1 state (Supplementary Fig. 39). These tentative findings are consistent with those of Solà and coworkers14 who concluded that the corresponding state for the parent COT is highly aromatic according to electronic indices. These calculations indicate that the COT ring of Th4 COT Saddle exhibits aromatic nature in the transition state in the T1 state and probably also in the S1 state, while in the S0 state it is antiaromatic.

Fig. 5.

Nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS) scans of Th4 COT Saddle and Th6 CDH Screw. a, b, Top and side views of the inversion transition states of Th4 COT Saddle (a) and Th6 CDH Screw (b) in the S0 and T1 states. c, d, NICSzz scans of Th4 COT Saddle (c) and Th6 CDH Screw (d), which start from the annulene ring center and scanned along the arrows shown in a and b. Black- and green-colored dots represent the scans in the S0 and T1 states, respectively

Interestingly, 16π-electron circuits are formed due to conjugation of the COT core and two adjacent fused thiophene rings in the minimum energy structures of the photoexcited Th4 COT Saddle. Although the minimum energy structures in the S1 and T1 states take a tub-shaped conformation (θ = 29.2° for S1 and 28.7° for T1 states; Fig. 4a), which is shallower than that in the S0 state (θ = 40.3°), they both have a bond-length equalized COT core. The ACID plot for the minimum energy structure in the T1 state showed clear 16π-electron diatropic ring currents, which comprise the central COT ring and two adjacent thiophene rings (Supplementary Fig. 35). Such 16π-electron diatropic ring currents were not observed in the minimum energy structure in the S0 state (Supplementary Fig. 33). The NICS(1)iso values were also consistent with the formation of a 16π conjugation pathway since both the COT ring (–8.9 ppm) and the thiophene rings (–7.3/–4.4 ppm above and below the ring, respectively) have negative NICS values. This is in sharp contrast with the NICS (1)iso values in the S0 state: 0.0 ppm for COT and –6.8/–7.6 ppm (above/below) for the surrounding thiophene rings (Supplementary Table 7). These observations indicate some aromatic character due to 16π-electron circuits in the minimum energy structure of the photoexcited Th4 COT Saddle. This highlights that a careful analysis that considers aromatic circuits from several rings is needed also for polycyclic systems in the excited state, similar as in the ground state47, 48.

So why is the tub conformation preferred, even in the excited state? Calculations were performed on the model compound Th2 COT Saddle, where two diagonally placed thiophene rings are removed to reduce steric repulsions. The optimization demonstrated that Th2 COT Saddle in the photoexcited (S1/T1) states prefers to be planar, which is in sharp contrast with the photoexcited Th4 COT Saddle (Supplementary Fig. 30). In addition, the activation enthalpy for ring inversion in the S0 state is lowered to 6.3 kcal mol–1 for Th2 COT Saddle from a calculated value of 29.9 kcal mol–1 for Th4 COT Saddle, indicating the effect of reduced steric strain. According to these model calculations, the shallow tub-shaped minimum energy structures of photoexcited Th4 COT Saddle represent a balance between maximizing the aromatic conjugation and minimizing the steric strain. Consequently, although a planar structure is favoured if only electronic effects are important, Th4 COT Saddle prefers a bent conformation in the excited state due to steric repulsion between neighboring thiophene rings.

For highly twisted Th6 CDH Screw, DFT calculations showed multiple dihedral angles of ~90° in the [12]annulene core, indicating inhibition of full conjugation along the central core at the inversion transition states in the S0, S1, and T1 states (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 44). This is in line with the observed spin density map at the transition state, showing that triplet excitation is localized to only one part of the annulene core (Supplementary Fig. 32). The C–C bond-length profile in the core at the transition states in the S0, S1, and T1 states exhibits a clear alternating feature (Supplementary Fig. 41). These observations indicate the non-aromatic nature of the [12]annulene core of Th6 CDH Screw in the transition state. Because of the highly strained conformations of Th6 CDH Screw, we can only utilize NICS calculations for the transition state structures as a magnetic index of aromaticity. As shown in Fig. 5d, the near-zero values of the NICSzz scans orthogonal to the central rings (Fig. 5b) suggest the non-aromatic nature of Th6 CDH Screw. For the minimum energy structures, a non-aromatic nature is also expected for the S0 and T1 states because similar bond-length alternation and dihedral angle profiles were observed (Supplementary Figs. 43 and 45). The only exception is the minimum energy structure of the S1 state, where bond-length equalization and small dihedral angles were observed, indicating the emergence of aromaticity. This observation is consistent with the higher calculated activation enthalpy for the S1 state (31.3 kcal mol–1) compared to the S0 (25.2 kcal mol–1) and T1 (23.0 kcal mol–1) states, which could be attributed to the aromatic stabilization of the S1 minimum that is lost at the transition state.

Discussion

In 1972, Baird theoretically predicted that planar [4n]annulenes, which are energetically unfavorable in the electronic ground state according to Hückel’s rule, become favoured upon photoexcitation. Using a particular [4n]annulene (Th4 COT Saddle), which undergoes photo-accelerated ring inversion through its planar transition state (Fig. 1c), we succeeded in unambiguous experimental substantiation of Baird’s rule from an energetic viewpoint. Additional important support was provided by the lack of photochemical acceleration in the ring inversion of a non-planarizable [4n]annulene (Th6 CDH Screw; Fig. 1d). The energetic impact of Baird aromaticity (21–22 kcal mol–1), determined by the analysis of the ring inversion kinetics of Th4 COT Saddle, is noteworthy considering the stabilization energy of benzene of 28.8 kcal mol–1, estimated based on experimental heats of formation49. Our study will help tailoring the potential energy surfaces of cyclic π-conjugated hydrocarbons with 4n π-electrons in their photoexcited states. Such compounds, if planar in the excited states, contribute as a new family of aromatic motifs to the progress of an exciting but much less explored area of organic photochemistry and related materials science.

Methods

Studies on the ring inversion events of Th4COTSaddle and Th6CDHScrew

Th4 COT Saddle was subjected to chiral HPLC using hexane/CH2Cl2 (95/5 v/v) as eluent on a chiral DAICEL CHIRALPAK IF column (Supplementary Methods), and two well-separated enantiomer fractions were collected and evaporated to dryness at 25 °C. To the residue from the former or latter fraction was slowly added methylcyclohexane (3.0 mL), deaerated beforehand by Ar bubbling for 1 h, at 25 °C. The resulting solution was transferred to a quartz cuvette under Ar at 25 °C using a cannula to avoid contact with air and was utilized for the kinetic studies of the ring inversion of Th4 COT Saddle at 20 °C. As shown in Fig. 3c, plots of the CD intensity changes at 260 nm versus time gave the decay profiles in the S0 (blue), S1 (orange; excitation at 365 nm), and T1 (green; excitation at 420 nm with fluorenone) states. Th6 CDH Screw is more subject to thermal ring inversion than Th4 COT Saddle. Chiral HPLC separation of its enantiomers was conducted at 0 °C using hexane/EtOH (100/0.1 v/v) as eluent on a chiral DAICEL CHIRALPAK IA column (Supplementary Methods). To prevent thermal racemization, the collected enantiomer fractions were evaporated at –40 °C, and the residues were dissolved in chilled methylcyclohexane at –40 °C. At –20 °C under otherwise identical conditions, the resulting solutions were subjected to kinetic studies of the ring inversion of Th6 CDH Screw (Fig. 3d), and the CD intensity changes at 280 nm were plotted versus time. The kinetic analysis was performed according to the method described in the Supplementary Discussion.

Quantum chemical calculations

The molecular geometries in the S0 and T1 states were optimized using B3LYP50 augmented by D3(BJ) dispersion51 corrections and the 6–31G(d) basis set using Gaussian 09 Revision E.0152 (for full reference, see Supplementary References). Stationary points, including the minimum energy and transition state structures, were confirmed by frequency calculations. For the transition state structures, IRC analysis was further carried out. Single-point electronic energies were calculated using the 6–311+G(d,p) basis set and used together with the corrections to the enthalpy taken from B3LYP-D3(BJ)/6–31G(d). For the S1 state, we used TD-B3LYP/6–31+G(d,p) and both Gaussian 09 Revision E.0152 and Gaussian 16 Revision A.0353 (for full reference, see Supplementary References). The use of TD-DFT for the S1 surface was validated for Th4 COT Saddle by comparison with ab initio methods (Supplementary Methods). NICS scans were calculated with GIAO-B3LYP/6–311+G(d,p) using the Aroma 1.0 package43 (for full reference, see Supplementary References). ACID plots were calculated with CSGT-B3LYP/6–311+G(d,p).

Data availability

All relevant data are included in full within this paper and in the Supplementary Information.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Jun-ichi Aihara from Department of Chemistry, Shizuoka University for valuable discussions. We also thank Prof. Masahiro Yamanaka from Department of Chemistry, Rikkyo University for valuable discussions. K.J. and H.O. thank Prof. R. Herges for providing the AICD 2.0.0 program. This work was financially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (25000005) on “Physically Perturbed Assembly for Tailoring High-Performance Soft Materials with Controlled Macroscopic Structural Anisotropy” for T.A. and Y.I.; M.U. thanks JSPS for a Young Scientist Fellowship and the Program for Leading Graduate Schools (MERIT). The work at Yonsei University was supported by Samsung Science and Technology Foundation under Project Number SSTF-BA1402-10. H.O. and K.J. acknowledge the Swedish Research Council (project grant 2015-04538) for support. Financial supports by Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research, Challenging Exploratory Research, Promotion of Joint International Research (Fostering Joint International Research), and on Innovative Areas “Photosynergetics” (Grant Numbers JP15H03779, JP15K13642, JP16KK0111, and JP17H05261) from JSPS for T.M. is greatly acknowledged. Part of this work was conducted at the Advanced Characterization Nanotechnology Platform of the University of Tokyo, supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. The Swedish National Infrastructure for Computation (SNIC) through NSC, Linköping, and HPC2N, Umeå, is acknowledged for computer time. A portion of the computations was performed using Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan.

Author contributions

M.U., T.A., and Y.I. initiated the work on the ring inversion kinetics of thiophene-fused annulenes. K.J. and H.O. proposed the incorporation of Baird aromaticity. M.U. and Y.I. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. K.J. performed the calculations, and, together with H.O., analyzed the data. Y.M.S. performed the transient absorption spectroscopies, and, together with D.K., analyzed the data. T.M. provided the theoretical basis for analyzing the CD intensity decay profiles to obtain the energetics of the system. M.U., K.J., H.O., T.A., and Y.I. wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00382-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Dongho Kim, Email: dongho@yonsei.ac.kr.

Henrik Ottosson, Email: henrik.ottosson@kemi.uu.se.

Takuzo Aida, Email: aida@macro.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

Yoshimitsu Itoh, Email: itoh@macro.t.u-tokyo.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Spitler EL, Johnson CA, II, Haley MM. Renaissance of annulene chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:5344–5386. doi: 10.1021/cr050541c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleiter, R., Haberhauer, G. & Hoffmann, R. Aromaticity And Other Conjugation Effects (Wiley-VCH, 2012).

- 3.Hückel E. Quantentheoretische beiträge zum benzolproblem. I. Die elektronenkonfiguration des benzols und verwandter verbindungen. Z. Physik. 1931;70:204–286. doi: 10.1007/BF01339530. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paquette LA. The renaissance in cyclooctatetraene chemistry. Tetrahedron. 1975;31:2855–2883. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(75)80303-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klärner F-G. About the antiaromaticity of planar cyclooctatetraene. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:3977–3981. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011105)40:21<3977::AID-ANIE3977>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slayden SW, Liebman JF. The energetics of aromatic hydrocarbons: an experimental thermochemical perspective. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:1541–1566. doi: 10.1021/cr990324+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishinaga T, Ohmae T, Iyoda M. Recent studies on the aromaticity and antiaromaticity of planar cyclooctatetraene. Symmetry. 2010;2:76–97. doi: 10.3390/sym2010076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu JI, Fernández I, Mo Y, Schleyer P. v. R. Why cyclooctatetraene is highly stabilized: the importance of “two-way” (double) hyperconjugation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012;8:1280–1287. doi: 10.1021/ct3000553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baird NC. Quantum organic photochemistry. II. Resonance and aromaticity in the lowest 3ππ* state of cyclic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:4941–4948. doi: 10.1021/ja00769a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aihara J. Aromaticity-based theory of pericyclic reactions. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1978;51:1788–1792. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.51.1788. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ottosson H. Exciting excited-state aromaticity. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:969–971. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karadakov PB. Ground- and excited-state aromaticity and antiaromaticity in benzene and cyclobutadiene. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:7303–7309. doi: 10.1021/jp8037335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karadakov PB. Aromaticity and antiaromaticity in the low-lying electronic states of cyclooctatetraene. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:12707–12713. doi: 10.1021/jp8067365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feixas F, Vandenbussche J, Bultinck P, Matito E, Solà M. Electron delocalization and aromaticity in low-lying excited states of archetypal organic compounds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:20690–20703. doi: 10.1039/c1cp22239b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg M, Dahlstrand C, Kilså K, Ottosson H. Excited state aromaticity and antiaromaticity: opportunities for photophysical and photochemical rationalizations. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:5379–5425. doi: 10.1021/cr300471v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papadakis R, Ottosson H. The excited state antiaromatic benzene ring: a molecular Mr Hyde? Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:6472–6493. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00057B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan, P. & Krogh, E. Evidence for the generation of aromatic cationic systems in the excited state. Photochemical solvolysis of fluoren-9-ol. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1985, 1207–1208 (1985).

- 18.McAuley I, Krogh E, Wan P. Carbanion intermediates in the photodecarboxylation of benzannelated acetic acids in aqueous solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:600–602. doi: 10.1021/ja00210a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan P, Krogh E, Chak B. Enhanced formation of 8π(4n) conjugated cyclic carbanions in the excited state: first example of photochemical C–H bond heterolysis in photoexcited suberene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:4073–4074. doi: 10.1021/ja00220a076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krogh E, Wan P. Photodecarboxylation of diarylacetic acids in aqueous solution: enhanced photogeneration of cyclically conjugated eight π electron carbanions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:705–712. doi: 10.1021/ja00028a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ottosson H, et al. Scope and limitations of Baird’s theory on triplet state aromaticity: application to the tuning of singlet–triplet energy gaps in fulvenes. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:6998–7005. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberg M, Ottosson H, Kilså K. Influence of excited state aromaticity in the lowest excited singlet states of fulvene derivatives. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:12912–12919. doi: 10.1039/c0cp02821e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Möllerstedt H, Piqueras MC, Crespo R, Ottosson H. Fulvenes, fulvalenes, and azulene: are they aromatic chameleons? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13938–13939. doi: 10.1021/ja045729c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohamed RK, et al. The missing C1–C5 cycloaromatization reaction: triplet state antiaromaticity relief and self-terminating photorelease of formaldehyde for synthesis of fulvenes from enynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:15441–15450. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papadakis R, et al. Metal-free photochemical silylations and transfer hydrogenations of benzenoid hydrocarbons and graphene. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12962. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sung YM, et al. Reversal of Hückel (anti)aromaticity in the lowest triplet states of hexaphyrins and spectroscopic evidence for Baird’s rule. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:418–422. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sung YM, et al. Switching between aromatic and antiaromatic 1,3-phenylene-strapped [26]- and [28]hexaphyrins upon passage to the singlet excited state. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11856–11859. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oh J, et al. Aromaticity reversal in the lowest excited triplet state of archetypical Möbius heteroannulenic systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:6487–6491. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shukla D, Wan P. Evidence for a planar cyclically conjugated 8π system in the excited state: large stokes shift observed for dibenz[b,f]oxepin fluorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:2990–2991. doi: 10.1021/ja00060a063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan C, et al. A π‐conjugated system with flexibility and rigidity that shows environment-dependent RGB luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8842–8845. doi: 10.1021/ja404198h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garavelli M, et al. Cyclooctatetraene computational photo- and thermal chemistry: a reactivity model for conjugated hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:13770–13789. doi: 10.1021/ja020741v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsella MJ, Reid RJ, Estassi S, Wang L-S. Tetra[2,3-thienylene]: a building block for single-molecule electromechanical actuators. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12507–12510. doi: 10.1021/ja0255352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, et al. Efficient synthesis of trimethylsilyl-substituted dithieno[2,3-b:3′,2′-d]thiophene, tetra[2,3-thienylene] and hexa[2,3-thienylene] from substituted [3,3′]bithiophenyl. Synlett. 2007;15:2390–2394. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fratev F, Monev V, Janoschek R. Ab initio study of cyclobutadiene in excited states: optimized geometries, electronic transitions and aromaticities. Tetrahedron. 1982;38:2929–2932. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(82)85021-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gogonea V, Schleyer PvonR, Schreiner PR. Consequences of triplet aromaticity in 4nπ-electron annulenes: calculation of magnetic shieldings for open-shell species. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:1945–1948. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980803)37:13/14<1945::AID-ANIE1945>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zilberg S, Haas Y. Two-state model of antiaromaticity: the triplet state. Is Hund’s rule violated? J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:10851–10859. doi: 10.1021/jp9831031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrews LJ, Deroulede A, Linschitz H. Photophysical processes in fluorenone. J. Phys. Chem. 1978;82:2304–2309. doi: 10.1021/j100510a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kearns DR. Physical and chemical properties of singlet molecular oxygen. Chem. Rev. 1971;71:395–427. doi: 10.1021/cr60272a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan C, et al. Hybridization of a flexible cyclooctatetraene core and rigid aceneimide wings for multiluminescent flapping π systems. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:2193–2200. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gershoni-Poranne R, Stanger A. Magnetic criteria of aromaticity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:6597–6615. doi: 10.1039/C5CS00114E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herges R, Geuenich D. Delocalization of electrons in molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:3214–3220. doi: 10.1021/jp0034426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geuenich D, Hess K, Köhler F, Herges R. Anisotropy of the induced current density (ACID), a general method to quantify and visualize electronic delocalization. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:3758–3772. doi: 10.1021/cr0300901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahalkar, A. & Stanger, A. “Aroma” http://chemistry.technion.ac.il/members/amnon-stanger/

- 44.Stanger A. Nucleus-independent chemical shifts (NICS): distance dependence and revised criteria for aromaticity and antiaromaticity. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:883–893. doi: 10.1021/jo051746o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiménez-Halla JOC, Matito E, Robles J, Solà M. Nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS) profiles in a series of monocyclic planar inorganic compounds. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006;691:4359–4366. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2006.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Z, Wannere CS, Corminboeuf C, Puchta R, Schleyer P. v. R. Nucleus-independent chemical shifts (NICS) as an aromaticity criterion. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:3842–3888. doi: 10.1021/cr030088+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fias S, Fowler PW, Delgado JL, Hahn U, Bultinck P. Correlation of delocalization indices and current-density maps in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:3093–3099. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aihara J. Magnetic resonance energy and topological resonance energy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016;18:11847–11857. doi: 10.1039/C5CP06471F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mo Y, Schleyer PvR. An energetic measure of aromaticity and antiaromaticity based on the Pauling-Wheland resonance energies. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:2009–2020. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stephens PJ, Devlin FJ, Chabalowski CF, Frisch MJ. Ab initio calculation of vibrational absorption and circular dichroism spectra using density functional force fields. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:11623–11627. doi: 10.1021/j100096a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grimme S, Ehrlich S, Goerigk L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision E.01 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009).

- 53.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16, Revision A.03 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in full within this paper and in the Supplementary Information.