Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are ~22-nt single-stranded noncoding RNAs with regulatory roles in a wide range of cellular functions by repressing eukaryotic gene expression at a post-transcriptional level. Here, we analyzed the effects on meiosis and fertility of hypomorphic or null alleles of the HYL1, HEN1, DCL1, HST and AGO1 genes, which encode miRNA-machinery components in Arabidopsis. Reduced pollen and megaspore mother cell number and fertility were shown by the mutants analyzed. These mutants also exhibited a relaxed chromatin conformation in male meiocytes at the first meiotic division, and increased chiasma frequency, which is likely to be due to increased levels of mRNAs from key genes involved in homologous recombination. The hen1-13 mutant was found to be hypersensitive to gamma irradiation, which mainly causes double-strand breaks susceptible to be repaired by homologous recombination. Our findings uncover a role for miRNA-machinery components in Arabidopsis meiosis, as well as in the repression of key genes required for homologous recombination. These genes seem to be indirect miRNA targets.

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small (20–22 nt), single-stranded, non-coding RNAs encoded by endogenous loci: the MIR genes. In Arabidopsis, transcription of MIR genes by RNA polymerase II yields primary miRNA transcripts (pri-miRNAs) that fold into hairpin structures. The type III endoribonuclease DICER-LIKE-1 (DCL1), in coordination with the RNA-binding proteins SERRATE (SE), TOUGH (TGH) and HYPONASTIC LEAVES 1 (HYL1), binds and processes pri-miRNAs into miRNA precursors (pre-miRNAs). These pre-miRNAs are then cleaved into miRNA:miRNA* duplexes, which are stabilized by methylation at their 3′ ends by HUA ENHANCER 1 (HEN1). The HASTY (HST) exportin is thought to be required for nuclear export of miRNAs in Arabidopsis. Once in the cytoplasm, the miRNA strand of the miRNA:miRNA* duplex is loaded onto the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which contains an ARGONAUTE (AGO) protein. Complementary base pairing allows miRNAs to select their targets, and the ribonuclease AGO1 carries out gene silencing by slicing mRNAs or attenuating their translation1. AGO1 has also been detected in the nucleus, suggesting an alternative nuclear AGO1-RISC assembly2, 3.

Meiosis is a specialized cell division that yields new allele combinations in the gametes; it is essential for maintaining chromosome number across generations. Although miRNAs are known to regulate many aspects of plant growth and development, as well as hormonal and stress responses4, our understanding of their role in meiosis is very limited. Two miRNA families are required for sperm production in the male germline of mammals5, and distinct miRNAs are down- or up-regulated during reproductive development in plants6. Next generation sequencing identified 33 miRNAs in the Arabidopsis male gametophyte7, 8. Additionally, the so-called phased secondary siRNAs (phasiRNAs)—whose function and target genes remain elusive—are abundant during male gametogenesis in plants1, 9.

Several lines of evidence indicate a role for plant AGO proteins in meiosis. In rice, MEIOSIS ARRESTED AT LEPTOTENE 1 (MEL1), a core component of the male germline-specific RISC, is required for pollen grain development10, 11. AGO104, the maize ortholog of Arabidopsis AGO9, is involved in female meiosis12. Mutation of Arabidopsis AGO4, AGO6, AGO8 and AGO9 lead to abnormal female gametophyte precursors13, 14. In addition, the Arabidopsis ago2-1 mutant exhibits increased cell chiasma frequency in pollen mother cells (PMCs). Chiasma frequency and fertility are normal in Arabidopsis ago9-1, which displays a high frequency of chromosome interlocks from pachytene to metaphase15.

To gain insight on the role of the miRNA machinery in Arabidopsis meiosis, we analyzed the effects of hypomorphic or null alleles of AGO1, HYL1, HEN1, DCL1 and HST on fertility and meiosis. Mutations in these genes impair processes regulated by miRNAs, causing derepression of their target genes. Mutations in HEN1, AGO1 and DCL1 also alter pathways guided by other small RNAs16, 17. The mutants examined here share several meiotic phenotypes: decreased number of cells that enter meiosis, increased number of chiasmata, and partial chromosome decondensation from pachytene to metaphase I. These phenotypes could be associated with changes in the expression of genes involved in chromatin remodeling and homologous recombination (HR) in gamete-containing tissues. Interestingly, changes in the expression profiles of these genes are also found in somatic tissues from these mutants. Our results uncover a role for the miRNA pathway in the regulation of meiotic chromatin organization and HR.

Results

Fertility is impaired by mutations in miRNA-machinery genes

In Arabidopsis, loss-of-function of miRNA-machinery genes severely reduces fertility, leading to complete sterility or early lethality18. To investigate the causes of such sterility, we characterized meiosis in mutants carrying partial or complete loss-of-function alleles of genes involved in different steps of the miRNA pathway: DCL1 and HYL1, in miRNA precursor processing; HEN1, in miRNA:miRNA* duplex stabilization; HST, in nuclear export of miRNAs; and AGO1, in silencing of miRNA targets. The studied mutants were in the Col-0 and Ler genetic backgrounds, and carry different types of lesions (see Methods and Supplementary Table S1). Since null alleles of AGO1 and DCL1 cause early lethality precluding the study of meiosis, we used their hypomorphic and viable ago1-52 18 and dcl1-9 19 alleles. The alleles of HYL1, HEN1 and HST studied here are assumed to be null18.

To estimate the extent of fertility in the mutants under study, we determined the number of seeds per silique. Only dcl1-9 and ago1-101 were completely sterile, while the remaining mutants displayed short siliques and a variable degree of semi-sterility with significant decreases in the number of seeds per silique (8.98 ± 0.98 in hen1-6, 9.00 ± 0.42 in hyl1-12, 7.50 ± 0.49 in hst-21, and 7.00 ± 1.78 in ago1-52) compared to their corresponding wild-types (44.5 ± 2.11 in Ler and 45.95 ± 3.60 in Col-0) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

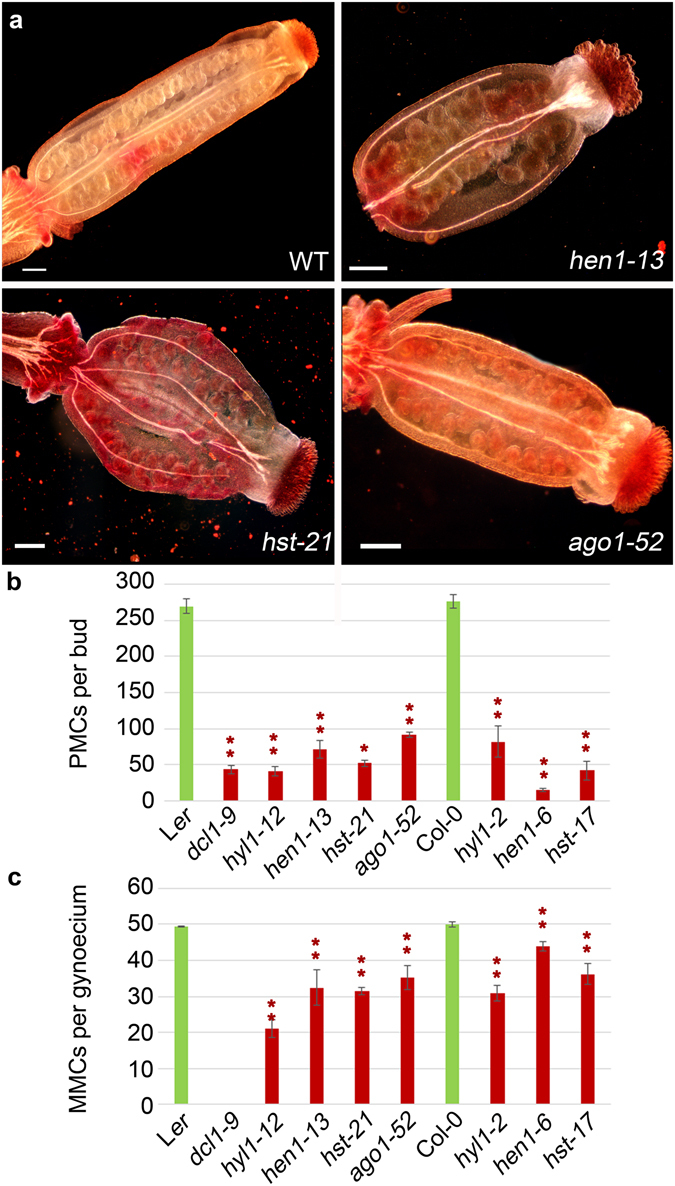

Since developmental alterations in flower organs and/or a reduction in the production of viable gametes might account for the observed decrease in fertility, we analyzed the number of PMCs per bud, and megaspore mother cells (MMCs) per gynoecium. The mutants displayed a reduction in PMCs ranging from 3-fold (in ago1-52) to 20-fold (in hen1-6) compared to their wild types (Fig. 1b). The reduction in MMC number was less severe, except for hyl1-12, which exhibited less than half of MMCs per gynoecium (21.00 ± 2.40) than Col-0 (49.40 ± 0.24; Fig. 1a,c). Our results agree with previous studies highlighting the poor transmission of the ago1-10 hypomorphic and hyl1-1 null alleles through male gametes20.

Figure 1.

Gynoecium morphology, and PMC and MMC number in the hen1-13, hst-21 and ago1-52 mutants. (a) Representative images of carmine staining of gynoecia from Ler and the hen1-13, hst-21 and ago1-52 mutants. (b) PMC number per bud. (c) MMC number per gynoecium. Asterisks indicate a significant difference with the corresponding wild type in a Mann-Whitney U test (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01).

Only the completely sterile ago1-101 and dcl1-9 mutants displayed abnormally shaped reproductive organs. Neither ovules (embryonic sacs) in the gynoecium nor PMCs in the anthers were observed in ago1-101 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Flowers with altered organ numbers (two gynoecia, three petals and three sepals) were occasionally seen in ago1-101. dcl1-9 showed a variable number of carpels, which sometimes fused to form a gynoecium, and numerous anthers (6 to 28) in different developmental stages. Pollen sacs occasionally embedded into carpel tissue were also observed (Supplementary Fig. S2). Aberrations in flower development have been previously reported for dcl1 mutants (initially named carpel factory)19.

Chromatin is decondensed at pachytene in most miRNA-machinery mutants

In Arabidopsis PMCs, the ten chromosomes appear as thread-like structures at leptotene, homologous synapsis starts at zygotene, and full synapsis is achieved at pachytene. Five bivalents are clearly observed after the disassembly of the synaptonemal complex (SC) at diplotene. Bivalents align at metaphase I plate and homologous chromosomes segregate to opposite poles at anaphase I. Four nuclei, each with a set of five chromatids, are formed during the second meiotic division.

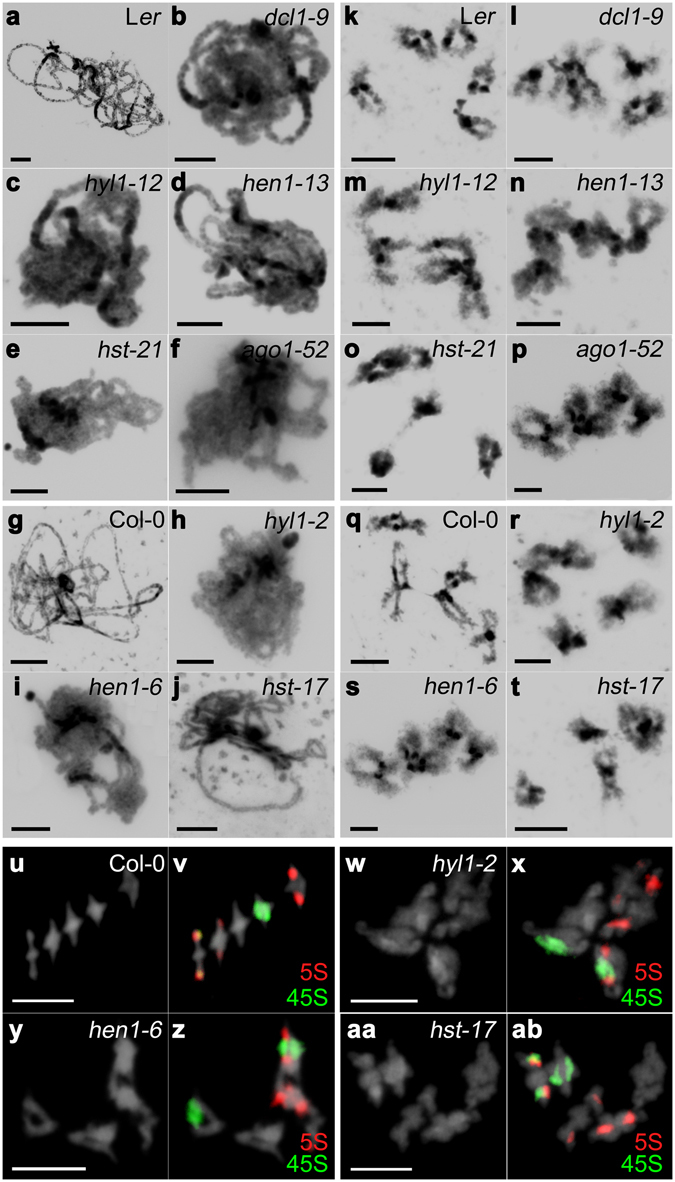

All mutants, except hst-17, showed chromatin decondensation at pachytene (Fig. 2a–j), i.e., absence of the characteristic chromomeric pattern in the bivalents, and at diakinesis (Fig. 2k–t). The percentage of decondensed male meiocytes ranged from 26% in hyl1-12 to 41% in hen1-13 (Fig. 2k–t, Table S5). At metaphase I, decondensed bivalents were observed in hen1-6, hst-17 and hyl1-2 (13, 31 and 21% of cells, respectively) (Fig. 2u–ab, Supplementary Table S2). No differential cytological features among mutant and wild-type plants were observed from anaphase I onwards (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 2.

Representative images of DAPI stained PMCs at pachytene and diakinesis, and FISH of metaphases I. (a–j) Pachytene. (k–t) Diakinesis. (u–ab) Diakinesis-Metaphase I. (a,k) Ler. (b,l) dcl1-9. (c,m) hyl1-12. (d,n) hen1-13. (e,o) hst-21. (f,p) ago1-52. (g,q,u,v) Col-0. (h,r,w,x) hyl1-2. (i,s,y,z) hen1-6. (j,t,aa,ab) hst-17. Mutant PMCs show a partial chromatin decondensation compared with wild type (see text for details). 5S rDNA is labeled in red and 45S rDNA in green. Bars = 5 µm.

Because the mutants showed decondensation at pachytene, the synaptic process was studied by immunodetection of the ASYNAPSIS 1 (ASY1) and ZYPPER 1 (ZYP1) proteins, which are related to the SC. At zygotene/pachytene, ASY1 localizes to the base of chromatin loops, which are in close association with the axial/lateral elements of meiotic chromosomes. ZYP1 is detectable at zygotene as foci or very short stretches when progressive SC formation takes place. Continuous ZYP1 lines at pachytene indicate achievement of full synapsis. We did not observe differences in the localization patterns of ASY1 and ZYP1 among our mutants and wild-type plants, indicating that synapsis occurred normally (as example see Supplementary Fig. S4 displaying the immunolocalization signals on a dcl1-9 PMC).

Histone H3 epigenetic marks are not altered in miRNA-machinery mutants

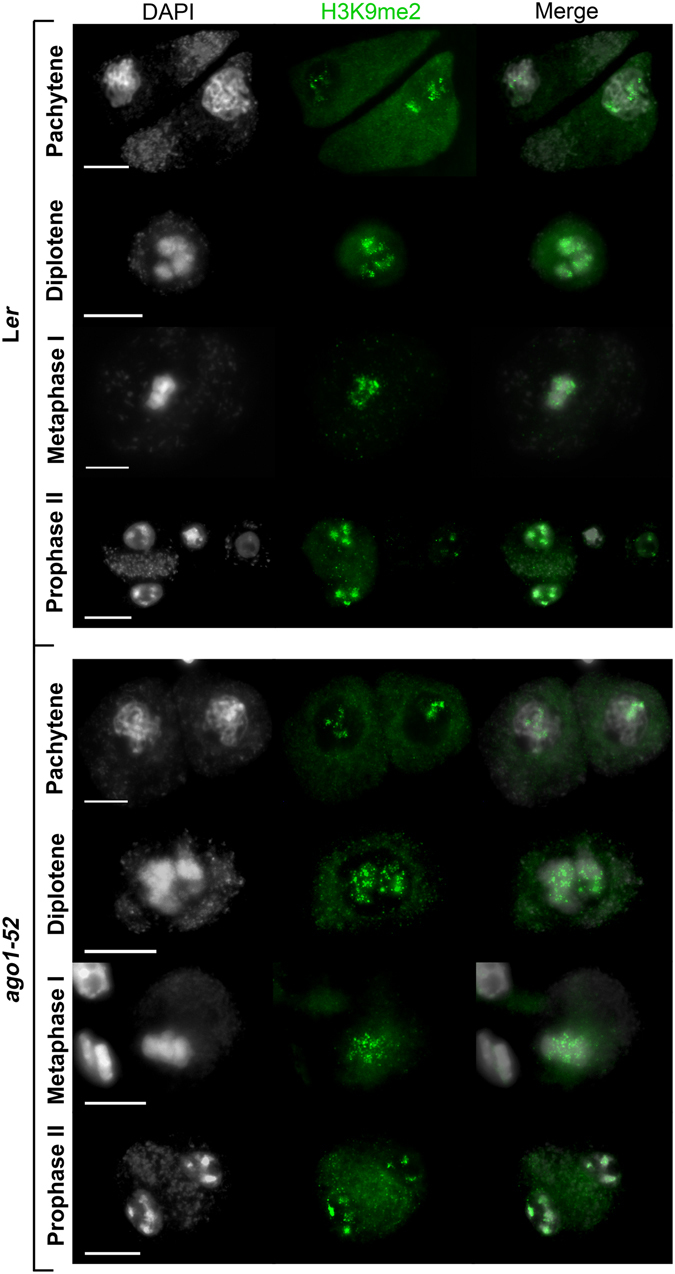

In Arabidopsis, dimethylation of lysine 9 (H3K9me2), which marks constitutive heterochromatin, is associated with condensation, while H3K4me2, H3K4me3, H3K27me3 and H3 acetylation (H3ac) specifically occur in decondensed euchromatin21. Serine 10 phosphorylation (H3S10Ph) specifically marks condensed chromatin. Chromosomes are only labeled with H3S10Ph at mitotic metaphase and from meiotic diplotene to metaphase I, and metaphase II. Different from other plant species, H3S10Ph marks are uniform along Arabidopsis chromosomes at these stages22. We analyzed the above-mentioned epigenetic marks in miRNA-machinery mutants, but the immunolabeling patterns observed were indistinguishable to those of their corresponding wild-type backgrounds. H3K9me2 was primarily restricted to the pericentromeric regions (Fig. 3). H3Ac immunosignals were invariably observed throughout meiosis (Supplementary Fig. S5). The immunolabeling patterns corresponding to H3K4me2, H3K4me3, and H3K27me3 were similar, being these modifications distributed across all chromosomes (Supplementary Figs S6–S8). We neither found differences of the chromosomal spatial and temporal distribution of H3S10Ph (Supplementary Fig. S9), since it appeared at late prophase I at the whole condensed chromosomes, disappearing at telophase I and reappearing at late prophase II. However, we cannot exclude specific differences affecting small chromosomal regions due to the limited resolution of the microscopic observations.

Figure 3.

Distribution of H3K9me2 in PMCs from Ler and ago1-52. Representative images of H3K9me2 immunolocalization, which marks constitutive heterochromatic regions. Similar results were obtained with the other mutants analyzed. Bars = 5 µm.

Genes involved in chromatin structure maintenance or modification are up-regulated in miRNA-machinery mutants

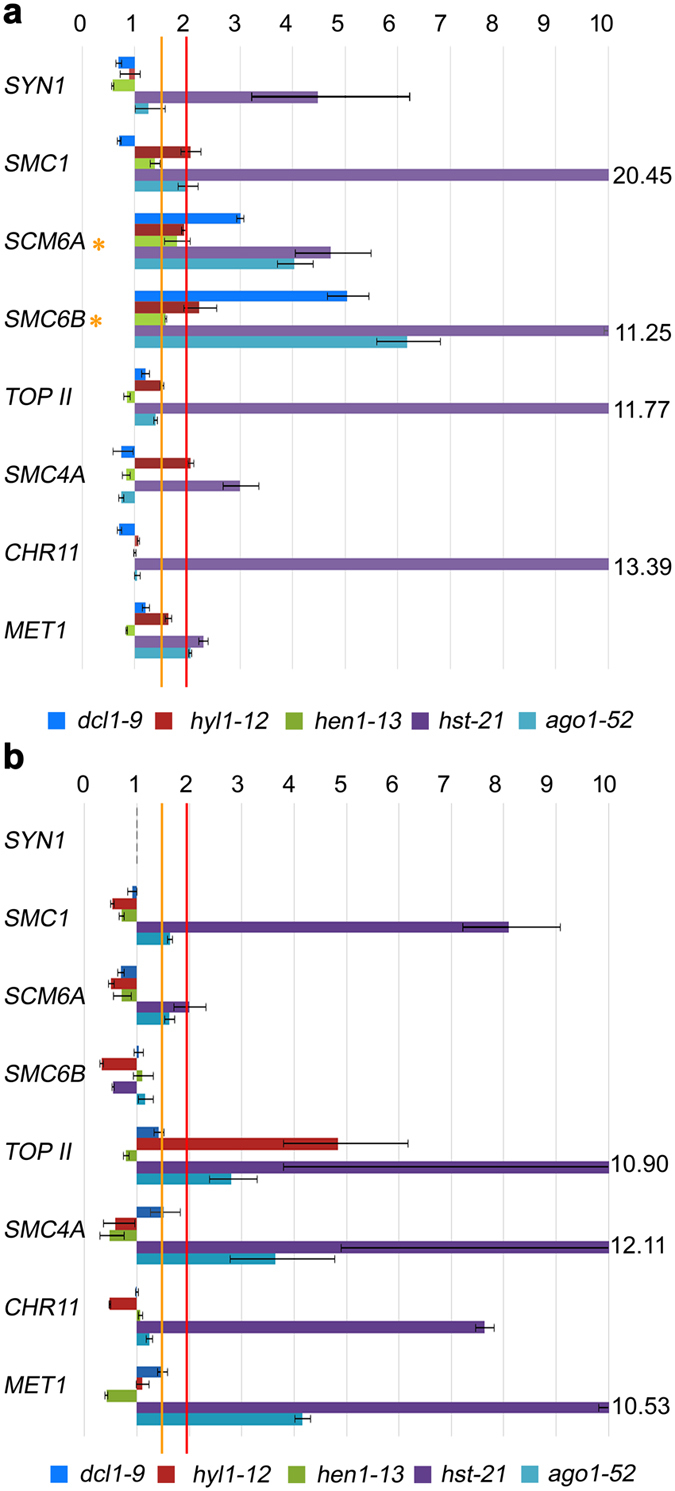

To ascertain the cause of the chromatin decondensation found in the mutants under study, we analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) the expression of genes involved in chromatin structure maintenance or modification. We analyzed the expression of SYNAPSIN 1 (SYN1), which encodes a meiotic-specific protein involved in sister chromatid cohesion and kinetochore orientation, and other genes with a role, both, at mitosis and meiosis: STRUCTURAL MAINTENANCE OF CHROMOSOMES 1 (SMC1), an essential gene for sister chromatid cohesion; SMC6A and SMC6B, which encode components of the SMC5/6 complex involved in DNA damage response by HR; TOPOISOMERASE II (TOPII), with an essential function in crossover (CO) resolution in budding yeast, whose expression is increased in proliferative tissues; SMC4A, which forms part of the condensin complex; CHROMATIN-REMODELING PROTEIN 11 (CHR11), implicated in cell proliferation during gametogenesis and sporophytic cell expansion; and METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 (MET1), involved in CpG methylation. In order to obtain a general view about the expression profile of these genes in miRNA-machinery mutants, we isolated total RNA from two tissue types: buds (enriched in meiocytes) and leaves. Most of the genes analyzed displayed unexpectedly high mRNAs levels in both organs. hst-21 and ago1-52 had quite similar mRNA profiles and overexpressed all the genes analyzed in buds, and many of them in leaves (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Relative expression assays of genes related to chromatin condensation. (a) Bud samples. (b) Leaf samples. Orange asterisks mark the genes that are overexpressed between 1.5- and 2.0-fold in all of the mutants compared with their wild types.

Several miRNAs have been detected in the male germline of Arabidopsis8. To investigate if the above-mentioned genes are miRNA targets, we used the psRNATarget Analysis Server (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/)23. Among 337 miRNAs in the psRNATarget database, miR5021 and miR161.2 were predicted to cleave the mRNA of TOPII, although the two target sites for miR5021 mapped at the 5′ UTR. In addition, miR866-5p was predicted to cleave the mRNA of SMC4A, and miR837-5p, to inhibit translation of this gene (Supplementary Table S3). miR5021 has been detected at very low level in pollen and considered a potential novel miRNA, because its genomic locus encodes an stem-loop miRNA precursor8. miR161.2 has been experimentally validated, targeting mRNAs of genes encoding proteins with pentatricopeptide repeats24. Degradome data support miR-837-5p as a true miRNA whose validated target is the mRNA of the gene encoding the Factor of DNA methylation 1 (FDM1), which is involved in RNA-directed DNA methylation25. miR866-5p co-immunoprecipitates at very low levels with AGO1 and has been identified in flower- and leaf-tissue small RNA libraries26.

Chiasma frequency is increased in miRNA-machinery mutants

Meiotic COs, manifested cytologically as chiasmata, are essential for fertility because they ensure correct segregation of homologous chromosomes at anaphase I. We examined chiasma frequency in miRNA-machinery mutants. To determine the number of chiasmata corresponding to each chromosome, we performed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) using probes against 45S and 5S rDNA repeats, which reside on chromosomes 2 and 4 (45S rDNA) and on chromosomes 3, 4 and 5 (5S rDNA)27. We found slight but statistically significant differences in several mutants (Table 1), which resulted from an increase in the number of chiasmata in the short arms of chromosomes 2 and 4, and in both arms of chromosome 5. Some mutants also showed a significant increase in chiasma frequency in the long arm of chromosome 2 (dcl1-9) and occasionally in the short arm of chromosome 3 (hen1-6; Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Mean chiasma frequencies per cell, per bivalent and per bivalent arm (short vs. long).

| Bivalents | C | n | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||||

| s | l | s | l | s | l | s | l | s | l | |||

| Ler | — | — | 0.56 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 1.16 | 9.38 | 63 |

| 2.35 (0.25) | 1.57 (0.17) | 1.97 (0.21) | 1.48 (0.16) | 2.02 (0.21) | ||||||||

| dcl1-9 | — | — | 0.71 | 1.17* | 0.98 | 1.10 | 0.76** | 1.05 | 1.00** | 1.34* | 10.59*** | 59 |

| 2.47 (0.23) | 1.88** (0.18) | 2.08 (0.20) | 1.81** (0.17) | 2.34** (0.22) | ||||||||

| hyl1-12 | — | — | 0.74* | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.72* | 1.02 | 0.94 | 1.20 | 10.02** | 50 |

| 2.42 (0.24) | 1.74 (0.17) | 1.98 (0.20) | 1.74* (0.17) | 2.14* (0.21) | ||||||||

| hen1-13 | — | — | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 1.07 | 0.59 | 1.06 | 0.94 | 1.27 | 9.91* | 70 |

| 2.44 (0.25) | 1.61 (0.16) | 2.00 (0.20) | 1.64 (0.17) | 2.21* (0.22) | ||||||||

| hst-21 | — | — | 0.78* | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.78** | 0.98 | 0.96 | 1.29 | 10.20*** | 45 |

| 2.38 (0.23) | 1.82* (0.18) | 2.00 (0.20) | 1.76** (0.17) | 2.24** (0.22) | ||||||||

| ago1-52 | — | — | 0.52 | 1.12 | 0.88 | 1.07 | 0.69 | 1.03 | 0.81 | 1.21 | 9.78 | 67 |

| 2.45 (0.25) | 1.64 (0.17) | 1.96 (0.20) | 1.72** (0.18) | 2.01 (0.21) | ||||||||

| Col-0 | — | — | 0.61 | 1.14 | 0.90 | 1.26 | 0.48 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.30 | 10.20 | 69 |

| 2.52 (0.25) | 1.75 (0.17) | 2.16 (0.21) | 1.49 (0.15) | 2.28 (0.22) | ||||||||

| hyl1-2 | — | — | 0.75 | 1.10 | 0.96 | 1.21 | 0.65 | 1.13 | 1.00 | 1.46 | 10.75* | 48 |

| 2.50 (0.23) | 1.85 (0.17) | 2.17 (0.20) | 1.77* (0.16) | 2.46 (0.23) | ||||||||

| hen1-6 | — | — | 0.63 | 1.13 | 1.00** | 1.50 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 10.88 | 8 |

| 2.75 (0.25) | 1.75 (0.16) | 2.50 (0.29) | 1.63 (0.15) | 2.25 (0.21) | ||||||||

| hst-17 | — | — | 0.79* | 1.13 | 0.90 | 1.25 | 0.58 | 1.08 | 0.94 | 1.33 | 10.60 | 48 |

| 2.60 (0.25) | 1.92 (0.18) | 2.15 (0.20) | 1.67 (0.16) | 2.27 (0.21) | ||||||||

C: mean cell chiasma frequencies. n: number of cells. s: short arm. l: long arm. For each genotype, the upper row indicates the mean chiasma frequency per bivalent arm (s and l); the bottom row includes the mean chiasma frequency per bivalent (s + l), and the contribution to the total chiasma frequency (as proportion of total cells) in parentheses. Asterisks indicate significant differences with the corresponding wild type in a Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

Genes involved in homologous recombination are up-regulated in miRNA-machinery mutants

To determine whether the observed increase in chiasma frequency results from de-regulation of genes involved in HR, we studied the genes mentioned below. SWITCH1 (SWI1) encodes a chromatin remodeling protein involved in the beginning of meiotic recombination and sister chromatid cohesion. SPORULATION11-1 (SPO11-1) encodes a topoisomerase involved in the formation of programmed DNA double-strand break (DSB) during early meiosis. ATAXIA-TELANGIECTASIA MUTATED (ATM) and ATAXIA TELANGIECTASIA-MUTATED AND RAD3-RELATED (ATR) encode two kinases involved in the phosphorylation of H2AX (γH2AX) at DSB sites. BREAST CANCER SUSCEPTIBILITY1 (BRCA1) and BRCA2B encode proteins involved in repairing damaged DNA. RAD50 encodes a component of the MRN complex (MRE11–RAD50–NBS1), which processes the DSBs to produce single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) ends where recombinases bind. RAD51C participates in DSB repair by HR. RAD51 encodes the main recombinase implicated in the repair of DSBs by HR, whereas DMC1 is the meiosis-specific homologue of RAD51. MutS HOMOLOG 4 (MSH4) and MutL PROTEIN HOMOLOG 3 (MLH3) encode two components of the pathway that leads to CO formation subjected to positive interference. MMS AND UV SENSITIVE 81 (MUS81) and FANCONI ANEMIA COMPLEMENTATION GROUP M (FANCM) encode antagonistic proteins acting in the pathway that leads to CO formation insensitive to interference. Once again, we examined RNA samples from buds and leaves, since HR is required for the repair of either DSBs that arise during the cell cycle or programmed DSB produced by SPO11 in meiocytes. We detected increased levels of mRNAs, compared to the wild-type plants, for most of these genes in buds and leaves, although with variations among different mutants. hst-21 showed the highest differences, and again ago1-52 and hst-21 displayed similar expression patterns, mainly in reproductive tissues (Figs 5 and 6).

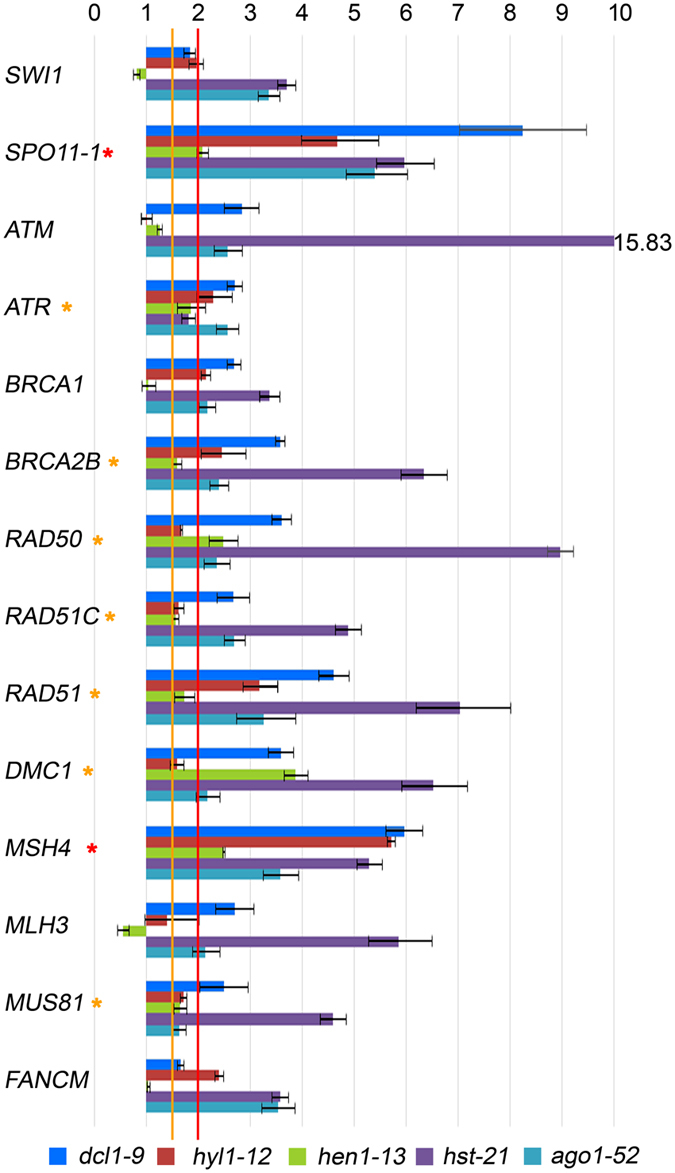

Figure 5.

Relative expression assays of some genes related to homologous recombination in bud samples. Red asterisks mark the genes that are overexpressed more than two-fold in all of the mutants compared with the wild type. Orange asterisks mark the genes that are overexpressed 1.5- to 2.0-fold.

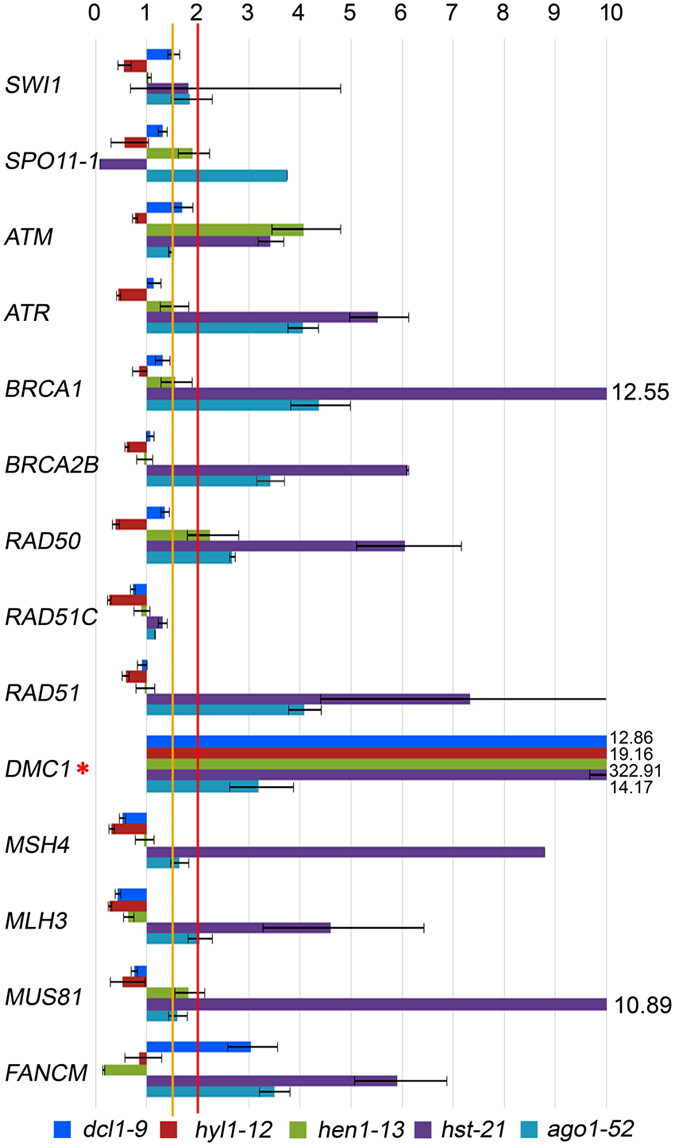

Figure 6.

Relative expression assays of genes related to homologous recombination in leaf samples. The red asterisk marks the DMC1 gene, which is overexpressed more than two-fold in all of the mutants compared with their wild types.

We also searched for miRNAs that might target the mRNAs of the above-mentioned genes, which are involved in HR and were found overexpressed in the mutants. According to psRNATarget, only two of those genes are predicted to be targeted by miRNAs, in both cases to cleave their mRNAs: SWI1 by miR414 and miR426, and MUS81 by miR854a-e (Supplementary Table S3). Mature miR854 is found in Arabidopsis rosette leaves, stems and flowers of wild-type plants, but not in those of dcl1, hyl1 and hen1 mutants28. It needs to be noted, however, that miR414 and miR426 are questioned as true miRNAs in the miRBase.

DMC1 is overexpressed in hen1-13

An unexpected result of our RT-qPCR analyses was the overexpression of the meiotic-specific recombinase DMC1 in all the mutants studied, not only in buds, but also in leaves. The expression level was especially high in leaves of hen1-13 (Fig. 6). Despite its meiotic-specific function, DMC1 is overexpressed in somatic tissues of the ddm1 mutant, which is defective for the DECREASE IN DNA METHYLATION 1 (DDM1) protein. DMC1 is also induced after treatment with the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2′deoxicytidine (5-AC)29. DMC1 forms foci with RAD51 at DSBs during meiosis. To examine the effects of an excess of DMC1 mRNA in meiosis, we performed a DMC1 immunolocalization in hen1-13 plants, but no differences with Ler were seen in the number of DMC1 foci (Supplementary Fig. S10). Therefore, either the excess mRNA produced or accumulated in the hen1-13 mutant is not translated to protein or, at least, the DMC1 protein does not form extra foci in our experimental conditions.

To determine if DMC1 overexpression could be associated to a defect in DNA repair, we tested the sensitivity of hen1-13 to gamma irradiation, which is known to cause severe genome damage, mainly DSBs. hen1-13 and Ler seeds were able to germinate after being irradiated at four different doses, but the mutant was significantly more sensitive at 300 Gy. At this dose, the mutant seeds germinated and the seedlings expanded their cotyledons, but they failed to produce leaves. At a higher dose (450 Gy), both Ler and hen1-13 seedlings failed to produce leaves (Supplementary Fig. S11).

RAD51 is involved in the repair of somatic DSBs, generated by DNA damage, as well as meiotic-programmed DSBs. The meiotic phenotype of the hen1-6 rad51-3 double mutant (both mutations are null and in a Col-0 background) was stronger than that of the rad51-3 single mutant, with higher levels of chromosome fragmentation at metaphase I-anaphase I (Supplementary Fig. S12), notwithstanding DMC1 is overexpressed in these plants. Furthermore, the double mutant showed trichomes with more than three branches, suggesting alterations in the endoreduplication control30. Increased endoreduplication should result from high levels of HR31. Altered trichomes were not observed in the single mutants (Supplementary Fig. S13).

Discussion

Loss-of-function alleles of miRNA-machinery genes cause semi-sterility in pollen mother cells

Many miRNA targets are mRNAs encoding transcription factors that control important developmental processes, such as organ patterning and development, flowering time, hormone regulation and meristem function20. Hence, mutations that damage miRNA-machinery components often lead to pleiotropic phenotypes19, 32, 33. In order to ascertain if the miRNA machinery participates in Arabidopsis meiosis and fertility, we studied these processes in ago1, hyl1, hen1, dcl1 and hst mutants. We found that the reproductive morphological and cytological phenotypes correlate in some, but not all these mutants. The complete sterility of dcl1-9 and ago1-101 might be an indirect consequence of abnormal development of their reproductive organs (Fig. S2). Indeed, the developmental programs controlling the number and morphology of reproductive organs are perturbed in the dcl1-9 mutant19 (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2). Similarly, the ago1-101 mutant produces inflorescences with aberrant flowers, including anthers that lack PMCs (Supplementary Fig. S2). The reduced fertility observed in the remaining mutants studied here cannot be attributed to developmental defects of their reproductive organs, whose morphology is indistinguishable from wild type. All of the miRNA-machinery mutants studied showed a decrease in the number of PMC and MMC per bud, assuming that there is a single MMC per embryo-sac. This reduction, which was more pronounced for the PMCs than the MMCs (Fig. 1), does not seem to be a direct consequence of meiotic alterations: no alterations in pairing, synapsis and homologous chromosome segregation were seen (Supplementary Figs S3 and S4). PMCs and MMCs originate from archesporial cells34. Genome instability produced by chromatin alterations in archesporial cells could affect premeiotic cell divisions. Certainly, such genome instability might be more severe for the male germline, since multiple mitoses are needed for the production of PMCs, whereas the female archesporial cell directly functions as a MMC35, 36.

Although the AGO1, DCL1, HST and HEN1 proteins are also involved in small RNA pathways other than that of miRNAs24, our results suggest that some miRNAs regulate germ-cell and somatic specification in anthers. Supporting this notion, loss-of-function alleles of genes involved in germ-cell line specification, such as BARELY ANY MERISTEM 1 and 2 (BAM1 and BAM2), EXCESS MICROSPOROCYTES 1 (EMS1), and SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE 1 and 2 (SERK1 and SERK2), display increased PMC numbers37. In addition, bioinformatic analyses suggest that BAM2, EMS1 and SERK2 might be regulated by miRNAs38. Transcripts from ARF6 and ARF8, encoding two Auxin Response Factors essential for correct gynoecium and stamen development, are targeted by miR167 39. Some other genes that control floral development, such as UNUSUAL FLORAL ORGANS (UFO), BLADE ON PETIOLE 1 (BOP1), APETALA 2 (AP2) and TERMINAL FLOWER 2 (TFL2)40–42, are predicted to be miRNA targets. Changes in the expression of one or more of these genes might explain the decrease in PMCs exhibited by the mutants studied here.

Loss-of-function mutations of miRNA-machinery genes affect chromatin condensation during first meiotic division

Histone modifications generate different chromatin configurations involved in a variety of basic cellular functions, such as transcriptional activity, DNA replication and repair, and chromosome recombination and segregation21. Previous studies have revealed the presence of chromatin condensation defects in mutants defective for RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway, in somatic cells during interphase43 and in post-meiotic male gametophytes44. Recently, we have also demonstrated that chromatin is disturbed in PMCs from mutant plants defective for several proteins related to RdDM. Here, our cytological observations suggest that genes of the miRNA machinery are important for maintaining chromatin structure and chromosome organization during early meiotic stages (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S2). Indeed, different types of small non-coding RNAs have been shown to participate in DNA and histone methylation45. Epigenetic silencing of transposable elements (TEs) is mediated by RNA-dependent DNA methylation (RdDM) guided by siRNAs. When TEs are epigenetically reactivated during germline reprogramming, TE transcripts are targeted by epigenetically activated small interfering RNAs (easiRNAs), whose biogenesis is directed by miRNAs46, 47. In fact, thousands of TEs were found up-regulated in isolated meiocytes in two RNA-seq searches for meiosis-specific genes48, 49, which highlights the importance of small RNA and miRNA-mediated regulation of meiosis in flowering plants. In addition, trans-acting small interfering RNAs (ta-siRNAs), which are generated after miRNA-directed cleavage of TAS gene transcripts, guide DNA methylation of TAS loci by RdDM. DCL1 is one of the genes involved in ta-siRNA-mediated RdDM50.

We found increased levels of mRNAs from genes involved in chromatin structure maintenance, which could be due to the direct or indirect action of miRNAs on these mRNAs. A recent analysis of 338 mature Arabidopsis miRNAs from the Plant microRNA Database (PMRD; http://bioinformatics.cau.edu.cn/PMRD)38 identified 2,862 potential targets51. These targets include several genes encoding proteins involved in histone modification, DNA methylation and chromatin remodeling, including SMC6A, TOPII and SWI1, whose mRNAs we found accumulated in the mutants studied here. In addition to SMC6A, other predicted target genes belong to the SMC family: SMC1 and SMC3, which encode proteins of the cohesin complex; and SMC2 and SMC4, which encode proteins of the condensin complex52. We found high levels of mRNAs from these SMC genes in bud samples of some of the mutants analyzed (Fig. 4). For example, the level of SMC1 mRNA detected in hst-21 was about 24-fold higher than that of Ler, and all mutants showed an increase of SMC6A and SMC6B mRNA amounts. SMC6A and SMC6B, together with SMC5, participate in DSB repair by HR53. Some other predicted miRNA targets encode proteins with a SWI domain, which are ATP-dependent and modify chromatin structure, modulating the access of transcription factors to DNA. For instance, the SWI1 gene encodes a protein involved in chromatin structure maintenance, sister chromatid cohesion establishment and axial element formation during meiosis54. Taken together, these prior observations and the results presented here suggest that the de-regulation of genes involved in chromatin structure maintenance, whose RNAs accumulate in the miRNA-machinery mutants studied here, cause the chromatin decondensation shown by these mutants.

Key genes of homologous recombination are up-regulated in miRNA-machinery mutants

High mRNA levels of the meiotic-specific genes SPO11-1 and MSH4 were found in buds of the mutants that we analyzed (Fig. 5). A more open chromatin conformation during prophase meiotic stages together with a high concentration of the SPO11-1 protein could cause an increase in the number of DSBs55. A subsequent overexpression of genes encoding proteins involved in the ulterior steps of the HR process would lead to a slight increase of reciprocal recombination events. This hypothesis might explain the increased mean cell chiasma frequency observed in dcl1-9, hyl1-2, hyl1-12, hen1-13 and hst-21 (Table 1). A variation in chiasma frequency has also been observed in the Arabidopsis arp6 mutant, defective for a component of the chromatin remodeling complex SWR1-C56, in which the expression of several MIR genes is altered57. In this context, specific cis-regulatory elements have been characterized in several genes preferentially expressed during male meiosis58. Regarding the results obtained in other species, a novel miRNA isolated in maize meiocytes has a predicted target sequence in RAD51C 9 and miR398 is more abundant in sunflower meiocytes from wild genotypes, which differ in recombination rates from domesticated genotypes59.

Accumulation of mRNAs from HR genes was also observed in leaf samples (Fig. 6). It is worth to mention that the number of miRNA targets might be underestimated in Arabidopsis. Between 30% and 60% of human genes are considered to be regulated by miRNAs, and some single miRNAs regulate more than one hundred genes60. Recent studies carried out in mammalian cell cultures have revealed that miRNA biogenesis is globally induced upon DNA damage in an ATM-dependent manner61. On the other hand, ATM and ATR are involved in the recruitment of the SMC5/SMC6 complex by H2AX phosphorylation, which might explain the increased SMC6A and SMC6B expression that we observed in miRNA-machinery mutants (Fig. 4). Taken together, our results show that components of the miRNA machinery are involved in the regulation of genes with effects on HR. Further studies will be required to determine whether these genes are direct or indirect targets of miRNAs.

The high overexpression of DMC1 in the leaves of all the mutants analyzed, especially hen1-6 (Fig. 6), was unexpected because DMC1, which encodes a meiosis-specific recombinase, has not been described as a miRNA target gene and its mRNA has not been previously found in leaf tissues. In fact, the DMC1 promoter is regularly used to drive meiosis-specific expression62, 63. However, we detected DMC1 expression in wild-type leaves (Fig. 6), and previous studies have suggested that the expression of this gene is not restricted to the germline29, 64. On the other hand, the excess of DMC1 mRNA produced in hen1-6 does not seem to be translated to protein (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Previous reports have demonstrated a link between the siRNA machinery genes AGO2 and AGO9 and DSB repair15, 65. In this study, we suggest the implication of HEN1 in this process. This is supported by the hen1-13 hypersensitivity to gamma-rays (Supplementary Fig. S11), and by the phenotype of the double mutant hen1-6 rad51-3, which displays increased endoreduplication in trichomes (Supplementary Fig. S13) and a higher level of chromosome fragmentation at metaphase I-anaphase I than that showed by rad51-3 meiocytes (Supplementary Fig. S12).

In conclusion, we have found a link between loss- and lack-of-function mutations in genes of the miRNA pathway and chromatin decondensation during meiosis; these mutations were also associated to a general overexpression of genes involved in meiotic recombination and chromatin organization. Despite these defects, meiosis seems to proceed normally. Given that not few miRNA targets encode transcription factors, it is tempting to propose that the miRNA machinery regulates at least some of the transcription factors that bind to the promoters of the genes that control either meiosis entry or chromatin remodeling and dynamics during this division. This study extends previous knowledge, but further experiments will be required to identify these regulatory elements and to discover the functional mechanism by which the miRNA machinery influences on meiosis and fertility.

Methods

Plant materials and growth

Plants of the Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Landsberg erecta (Ler) and Columbia-0 (Col-0) accessions were obtained from NASC (Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre). The ago1-52 and hst-21 mutations were induced by ethylmethane sulphonate (EMS), and hen1-13 and hyl1-12 by fast-neutrons, in a Ler background18, 66, 67. NASC also provided the dcl1-9 mutant, whose original background was Wassilewskija and was crossed five times to Ler 19. T-DNA insertional mutants from the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory (SiGnAL, http://signal.salk.edu/cgi-bin/tdnaexpress) were also provided by NASC: ago1-101, dcl1-16, hen1-6, hst-17, and hyl1-2 (Supplementary Table S1). The latter mutants were genotyped by PCR using a T-DNA-specific primer, either LBb1.3 or LB2, and two gene-specific primers (Supplementary Table S4). All plants were grown on a mixture of vermiculite and commercial soil (3:1) and kept in a greenhouse under a 16-hour light/8-hour dark photoperiod, at 20 °C and 70% relative humidity.

Fertility evaluation

To evaluate the extent of fertility of the mutants, we determined the number of seeds per silique, and the number of PMCs and MMCs. The number of seeds per silique was scored in three siliques from five plants of each genotype. The number of PMCs was determined in five buds from three plants of each genotype, which in all cases contained six anthers. The quantification of MMCs was carried out scoring embryonic sacs from squash preparations of five gynoecia from three plants of each genotype.

Cytology

Fixation of flower buds, slide preparation of PMCs, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) were carried out as previously described27. Three plants of each mutant and their corresponding wild types were analyzed. Squash preparations were made removing gynoecia from fixed flowers. The gynoecia were transferred to a slide, stained with acetic carmine and squashed. Immunolocalization of modified histone H3 was carried out as previously described, with some modifications22. Immunolocalizations of ASY1 (1:1000), ZYP1 (1:500) and DMC1 (1:250) proteins were carried out as previously described68 with the primary antibodies shown in Supplementary Table S5. The secondary antibodies were anti-rabbit IgG FITC conjugated (1:50, Sigma) and anti-rat IgG Cy3 conjugated (1:50, Sigma).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) from 100 mg of leaves and young buds of Ler, dcl1-9, hyl1-12, hen1-13, hst-21, and ago1-52. qPCR was performed with the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit and the FastStart TaqMan Probe Master kit using UPL (Roche, Universal Probe Library) probes, designed by the UPL Assay Design Center (https://lifescience.roche.com; Supplementary Table S6). The relative quantification of gene expression was monitored after normalization by the 18S rRNA as an internal control (Hs99999901_s1; Applied Biosystems, http://www.appliedbiosystems.com), considering fold variation over a calibrator (Ler) using the ΔΔC T method.

DNA damage sensitivity assays

Seeds from Ler and hen1-13 were kept in sterile water at 4 °C for 24 h and then exposed to 150, 300, and 450 Gy (with dose rates of 2.94 Gy/min) from a 137Cs source (IBL 437 C CIS bio International). Production of true leaves and fresh weight were scored 14 days after treatment.

miRNA target prediction

The psRNATarget website (http://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget)23 was used to check whether the mRNAs of selected genes (including SWI1, DYAD, SPO11, ATM, ATR, BRCA1, BRCA2b, RAD50, RAD51, RAD51C, DMC1, MSH4, MLH3, MUS81, FANCM, SYN1, SMC1, SMC6A, SMC4, TOPII, CHR11 and MET1) are miRNA targets. Default settings were used, as previously described69. For target search, the “Arabidopsis thaliana, transcript, removed miRNA gene, TAIR, version 10, released on 2010_12_14” library was selected.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad of Spain (grants AGL2012-38852 and AGL2015-67349-P to JLS, and BIO2014-56889-R to MRP), the European Union Framework Program 7 (Meiosys-KBBE-2009-222883 to JLS) and the Generalitat Valenciana (PROMETEOII/2014/006 to MRP). We are very grateful to Prof. José Luis Micol and Prof. Héctor Candela for comments on the manuscript, and Dr. Enrique Sánchez Molano and Diego Bersabé for their help with the statistical analyses.

Author Contributions

C.O., M.P., S.J.G., M.R.P. and J.L.S. conceived and designed the experiments and wrote the paper. C.O., M.P., S.J.G. and N.C. performed the experiments. C.O., M.P., S.J.G., M.R.P. and J.L.S. analyzed the data.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07702-x

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

María Rosa Ponce, Email: mrponce@umh.es.

Juan Luis Santos, Email: jlsc53@bio.ucm.es.

References

- 1.Borges F, Martienssen RA. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015;16:727–741. doi: 10.1038/nrm4085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang Y, Spector DL. Identification of nuclear dicing bodies containing proteins for microRNA biogenesis in living Arabidopsis plants. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomeranz MC, et al. The Arabidopsis tandem zinc finger protein AtTZF1 traffics between the nucleus and cytoplasmic foci and binds both DNA and RNA. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:151–165. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.145656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ameres SL, Zamore PD. Diversifying microRNA sequence and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:475–488. doi: 10.1038/nrm3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilz S, Fogarty EA, Modzelewski AJ, Cohen PE, Grimson A. Transcriptome profiling of the developing male germ line identifies the miR-29 family as a global regulator during meiosis. RNA Biol. 2016;14:219–235. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1270002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo Y, Guo Z, Li L. Evolutionary conservation of microRNA regulatory programs in plant flower development. Dev. Biol. 2013;380:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant-Downton R, et al. MicroRNA and tasiRNA diversity in mature pollen of Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:643. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borges F, Pereira PA, Slotkin RK, Martienssen RA, Becker JD. MicroRNA activity in the Arabidopsis male germline. J. Exp. Bot. 2011;62:1611–1620. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dukowic-Schulze, S. et al. Novel meiotic miRNAs and indications for a role of phasiRNAs in meiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Komiya R, et al. Rice germline-specific Argonaute MEL1 protein binds to phasiRNAs generated from more than 700 lincRNAs. Plant J. 2014;78:385–397. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nonomura K-I, et al. A germ cell specific gene of the ARGONAUTE family is essential for the progression of premeiotic mitosis and meiosis during sporogenesis in rice. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2583–2594. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh M, et al. Production of viable gametes without meiosis in maize deficient for an ARGONAUTE protein. Plant Cell. 2011;23:443–458. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olmedo-Monfil V, et al. Control of female gamete formation by a small RNA pathway in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2010;464:628–632. doi: 10.1038/nature08828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez-Lagana E, Rodriguez-Leal D, Lua J, Vielle-Calzada JP. A multigenic network of ARGONAUTE4 clade members controls early megaspore formation in Arabidopsis. Genetics. 2016;204:1045–1056. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.188151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oliver C, Santos JL, Pradillo M. On the role of some ARGONAUTE proteins in meiosis and DNA repair in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:177. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eamens A, Wang M-B, Smith NA, Waterhouse PM. RNA silencing in plants: yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:456–468. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.117275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, et al. Deep sequencing of small RNAs specifically associated with Arabidopsis AGO1 and AGO4 uncovers new AGO functions. Plant J. 2011;67:292–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jover-Gil S, et al. The microRNA pathway genes AGO1, HEN1 and HYL1 participate in leaf proximal-distal, venation and stomatal patterning in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:1322–1333. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobsen SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM. Disruption of an RNA helicase/RNAse III gene in Arabidopsis causes unregulated cell division in floral meristems. Development. 1999;126:5231–5243. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kidner CA, Martienssen RA. The role of ARGONAUTE1 (AGO1) in meristem formation and identity. Dev. Biol. 2005;280:504–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs J, Demidov D, Houben A, Schubert I. Chromosomal histone modification patterns – from conservation to diversity. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oliver C, Pradillo M, Corredor E, Cuñado N. The dynamics of histone H3 modifications is species-specific in plant meiosis. Planta. 2013;238:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1885-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai X, Zhao PX. psRNATarget: a plant small RNA target analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W155–159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Carrington JC. microRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell. 2005;121:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jha A, Shankar R. miRNAting control of DNA methylation. J. Biosci. (Bangalore) 2014;39:365–380. doi: 10.1007/s12038-014-9437-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeong DH, et al. Comprehensive investigation of microRNAs enhanced by analysis of sequence variants, expression patterns, ARGONAUTE loading, and target cleavage. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1225–1245. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.219873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sánchez-Morán E, Armstrong SJ, Santos JL, Franklin FC, Jones GH. Chiasma formation in Arabidopsis thaliana accession Wassileskija and in two meiotic mutants. Chromosome Res. 2001;9:121–128. doi: 10.1023/A:1009278902994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arteaga-Vazquez M, Caballero-Perez J, Vielle-Calzada JP. A family of microRNAs present in plants and animals. Plant Cell. 2006;18:3355–3369. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudson K, Luo S, Hagemann N, Preuss D. Changes in global gene expression in response to chemical and genetic perturbation of chromatin structure. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edgar BA, Zielke N, Gutierrez C. Endocycles: a recurrent evolutionary innovation for post-mitotic cell growth. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014;15:197–210. doi: 10.1038/nrm3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Endo M, et al. Increased frequency of homologous recombination and T-DNA integration in Arabidopsis CAF-1 mutants. EMBO J. 2006;25:5579–5590. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohmert K, et al. AGO1 defines a novel locus of Arabidopsis controlling leaf development. EMBO J. 1998;17:170–180. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen X, Liu J, Cheng Y, Jia D. HEN1 functions pleiotropically in Arabidopsis development and acts in C function in the flower. Development. 2002;129:1085–1094. doi: 10.1242/dev.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grossniklaus U. Plant germline development: a tale of cross-talk, signaling, and cellular interactions. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2011;24:91–95. doi: 10.1007/s00497-011-0170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grossniklaus U, Schneitz K. The molecular and genetic basis of ovule and megagametophyte development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1998;9:227–238. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang WC, Ye D, Xu J, Sundaresan V. The SPOROCYTELESS gene of Arabidopsis is required for initiation of sporogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear protein. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2108–2117. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang F, Wang Y, Wang S, Ma H. Molecular control of microsporogenesis in Arabidopsis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011;14:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z, et al. PMRD: plant microRNA database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D806–D813. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu MF, Tian Q, Reed JW. Arabidopsis microRNA167 controls patterns of ARF6 and ARF8 expression, and regulates both female and male reproduction. Development. 2006;133:4211–4218. doi: 10.1242/dev.02602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levin JZ, Meyerowitz EM. UFO: an Arabidopsis gene involved in both floral meristem and floral organ development. Plant Cell. 1995;7:529–548. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.5.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsson AS, Landberg K, Meeks-Wagner DR. The TERMINAL FLOWER2 (TFL2) gene controls the reproductive transition and meristem identity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 1998;149:597–605. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.2.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alvarez J, Smyth DR. CRABS CLAW and SPATULA, two Arabidopsis genes that control carpel development in parallel with AGAMOUS. Development. 1999;126:2377–2386. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pontes O, Costa-Nunes P, Vithayathil P, Pikaard CS. RNA polymerase V functions in Arabidopsis interphase heterochromatin organization independently of the 24-nt siRNA-directed DNA methylation pathway. Mol. Plant. 2009;2:700–710. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schoft VK, et al. Induction of RNA-directed DNA methylation upon decondensation of constitutive heterochromatin. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1015–1021. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zilberman D, Cao X, Jacobsen SE. ARGONAUTE4 control of locus-specific siRNA accumulation and DNA and histone methylation. Science. 2003;299:716–719. doi: 10.1126/science.1079695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Creasey KM, et al. miRNAs trigger widespread epigenetically activated siRNAs from transposons in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2014;508:411–415. doi: 10.1038/nature13069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCue AD, et al. ARGONAUTE 6 bridges transposable element mRNA-derived siRNAs to the establishment of DNA methylation. EMBO J. 2015;34:20–35. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen C, et al. Meiosis-specific gene discovery in plants: RNA-Seq applied to isolated Arabidopsis male meiocytes. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang H, Lu P, Wang Y, Ma H. The transcriptome landscape of Arabidopsis male meiocytes from high-throughput sequencing: the complexity and evolution of the meiotic process. Plant J. 2011;65:503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu L, Mao L, Qi Y. Roles of dicer-like and argonaute proteins in TAS-derived small interfering RNA-triggered DNA methylation. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:990–999. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.200279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meng J, Shi L, Luan Y. Plant microRNA-target interaction identification model based on the integration of prediction tools and support vector machine. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wood AJ, Severson AF, Meyer BJ. Condensin and cohesin complexity: the expanding repertoire of functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:391–404. doi: 10.1038/nrg2794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watanabe K, et al. The STRUCTURAL MAINTENANCE OF CHROMOSOMES 5/6 complex promotes sister chromatid alignment and homologous recombination after DNA damage in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2688–2699. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.060525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mercier R, et al. The meiotic protein SWI1 is required for axial element formation and recombination initiation in Arabidopsis. Development. 2003;130:3309–3318. doi: 10.1242/dev.00550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cole F, et al. Homeostatic control of recombination is implemented progressively in mouse meiosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:424–430. doi: 10.1038/ncb2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Choi K, et al. Arabidopsis meiotic crossover hot spots overlap with H2A.Z nucleosomes at gene promoters. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1327–1336. doi: 10.1038/ng.2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi K, et al. Regulation of microRNA-mediated developmental changes by the SWR1 chromatin remodeling complex in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:1128–1143. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li J, Yuan J, Li M. Characterization of putative cis-regulatory elements in genes preferentially expressed in Arabidopsis male meiocytes. BioMed Research Int. 2014;2014:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2014/708364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flórez-Zapata, N. M. V., Reyes-Valdés, M. H. & Martínez, O. Long non-coding RNAs are major contributors to transcriptome changes in sunflower meiocytes with different recombination rates. BMC Genomics17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Friedman RC, Farh KKH, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2008;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang X, Wan G, Berger FG, He X, Lu X. The ATM kinase induces microRNA biogenesis in the DNA damage response. Mol. Cell. 2011;41:371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stevens R, et al. A CDC45 homolog in Arabidopsis is essential for meiosis, as shown by RNA interference-induced gene silencing. Plant Cell. 2004;16:99–113. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Z, Makaroff CA. Arabidopsis separase AESP is essential for embryo development and the release of cohesin during meiosis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1213–1225. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Van EF, Verweire D, Claeys M, Depicker A, Angenon G. Evaluation of seven promoters to achieve germline directed Cre-lox recombination in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2009;28:1509–1520. doi: 10.1007/s00299-009-0750-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wei W, et al. A role for small RNAs in DNA double-strand break repair. Cell. 2012;149:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berná G, Robles P, Micol JL. A mutational analysis of leaf morphogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 1999;152:729–742. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.2.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jover-Gil S, Candela H, Ponce MR. Plant microRNAs and development. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2005;49:733–744. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052015sj. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Armstrong SJ, Caryl AP, Jones GH, Franklin FCH. Asy1, a protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis, localizes to axis-associated chromatin in Arabidopsis and Brassica. J. Cell Sci. 2002;115:3645–3655. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jover-Gil S, Paz-Ares J, Micol JL, Ponce MR. Multi-gene silencing in Arabidopsis: a collection of artificial microRNAs targeting groups of paralogs encoding transcription factors. Plant J. 2014;80:149–160. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.