Growth in prescription drug costs since 1996 has set a new record. Not since World War II has drug spending escalated so rapidly for such a prolonged period. The latest figures published by the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) show that prescription-only medicines cost $18 billion in 2004.1 Growing at a pace of over $1.5 billion per year, prescription costs have sailed well past the payments for all services provided by physicians ($16 billion). Given that the annual increase in prescription drug costs could finance the services of 3500 new physicians every year, patterns of drug utilization and spending deserve careful scrutiny.

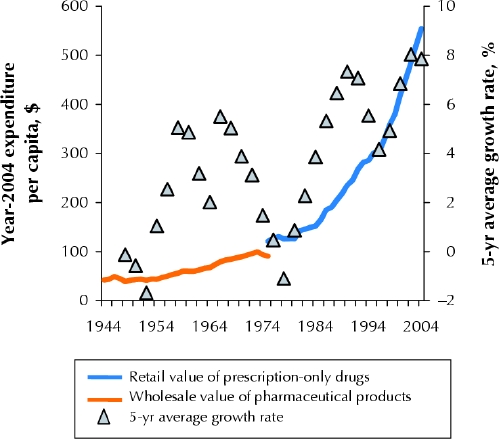

Fig. 1 illustrates trends in expenditures on pharmaceutical products from 1944 to 2004. After a brief post-war contraction in drug manufacturing, Canada experienced accelerated pharmaceutical spending during the “therapeutic revolution” that brought newly patented anti-infective agents and many sulfanilamide-related drugs to market in the 1950s and 1960s. Rapid growth in drug use and costs in this era led to formal inquiries into industry conduct in Canada.2 Concerns focused on aggressive promotion of new medicines and allegations of anticompetitive pricing. Although relatively few cost-control measures were put into place following these inquiries, pharmaceutical spending decreased in the 1970s. The down-turn was a global one and has been attributed to fewer discoveries of new chemicals and the expiry of patents on several post-war innovations.

Fig. 1: Trends in expenditures on pharmaceutical products from 1944 to 2004. Shown are values derived from Statistics Canada's historical data on pharmaceutical manufacturers' sales (orange line) and more recent data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) on retail spending (blue line). Per capita spending has been adjusted for general inflation and is expressed in terms of year-2004 purchasing power. The 5-year average growth rates (triangles) in inflation-adjusted per capita expenditures illustrate spending cycles over the past 60 years.

The decline in spending was short-lived: beneath the spending trends in the 1970s, the pharmaceutical sector was undergoing another revolution that would ultimately lead to rapid growth in the 1980s. Advances in receptor theory in pharmacology and improved screening techniques ushered in the era of “rational drug design.” Rather than screening compounds for pharmacologic effect in a relatively untargeted manner, scientists began to design or search for compounds that would “fit” with specific receptor sites. This era of therapeutics produced many innovations and major improvements in existing treatment options. During this wave of discovery, manufacturers competing within breakthrough drug classes set new standards of promotional intensity. Histamine-2 receptor antagonists are a leading example. Providing unquestionable improvements over existing alternatives, cimetidine and ranitidine were promoted with an intensity that earned them the Hollywood analogy of “blockbuster drugs.” Respectively, these were the first and second drugs to achieve billion-dollar annual sales.

In the mid 1980s, another inquiry into pharmaceutical industry conduct was launched in Canada.3 The recommendations generated from this inquiry ranged from patent policy to regulatory processes, but they did not lead to substantial reforms to drug coverage policy or cost control. As had happened following earlier periods of rapid growth, the global pharmaceutical industry experienced a short period of relatively modest expansion in the mid 1990s. Unlike previous cycles in drug spending, inflation-adjusted expenditure per capita did not fall at this time; rather, spending continued to grow, albeit at a relatively slow rate, from 1993 to 1996.

Then, starting in 1997, drug expenditures in North America set off on an unprecedented trajectory. Inflation-adjusted per capita drug expenditure in Canada grew more rapidly over the 8 years that followed than at any other period in the post-war era. Total spending in prescription drugs more than doubled, from $7.6 billion in 1996 to $18.0 billion in 2004. This increase was unique because, unlike in other eras, most of the recent growth was linked to drug classes discovered a decade earlier. Increased use and costs of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, statins and proton pump inhibitors explain nearly half of recent increases in Canada's drug expenditures.4 All of these drug types were discovered before the 1990s.

If there has been a recent “revolution” in the pharmaceutical industry, it was one of marketing and promotion. In stark contrast with past promotional practices, drug marketing since the mid-1990s has targeted patients directly. The year 1997 was the watershed for this phenomenon. It is the year that American regulators relaxed restrictions on television, print and radio advertising for prescription-only drugs. By 2003, US$3.2 billion was spent on direct-to-consumer advertising in the United States (7 times the amount spent on advertising in professional journals). Many Canadians are exposed to US ads through television, the Internet, magazines and radio. They are also exposed to “made in Canada” ads that promote products without explicit mention of their indicated uses.

The results are predictable: patients ask about advertised treatments, doctors are often accommodating, and the drugs prescribed are increasingly those that are most heavily advertised. More prescriptions and the prescribing of more expensive drugs turn out to be the main causes of the recent increases in Canadian drug spending.4

Should we blame the drug manufacturers and do what we have done in the past — start another inquiry into their conduct? No. The industry's conduct has been much studied and is highly predictable. It is not the responsibility of drug manufacturers, nor is it within their capacity as for-profit firms, to weigh the benefits and costs of treatment options being prescribed to Canadians. That responsibility belongs to practitioners and policy-makers.

What we truly need to do is examine the evidence base on which policy and practice rest. If it has been in the public interest to raise consumers' awareness of conditions such as hypertension and high cholesterol, why have governments and health care professionals left the task to for-profit manufacturers rather than mount such information campaigns using public funds? If product selection decisions are critical to both outcomes and costs, why do we depend so heavily on information from profit-driven manufacturers rather than provide practitioners with a timely and functional source of independent information concerning treatment options? Perhaps the most important question is why $18 billion is spent on prescription drugs every year without any systematic investment in monitoring and evaluating who is using the drugs, how they are using them and what the outcomes are in the real world. At $18 billion per year, investment in pharmaceutical products should not be made on faith in promised outcomes. With more patients taking more drugs over longer periods, it is vital to the safety of Canadians and the sustainability of our health care system to disseminate unbiased information, monitor the use of prescription drugs and detect both expected and unexpected outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Steve Morgan is supported in part by career awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Steve Morgan, Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, University of British Columbia, 429–2194 Health Sciences Mall, Vancouver BC V6T 1Z3; morgan@chspr.ubc.ca

References

- 1.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Drug expenditure in Canada 1985 to 2004. Ottawa: The Institute; 2005.

- 2.Canada. Report concerning the manufacture, distribution and sale of drugs. Ottawa: Department of Justice; 1963.

- 3.Canada. Report of the Commission of Inquiry on the Pharmaceutical Industry. Ottawa: Supply and Services Canada; 1985.

- 4.Morgan SG. Drug spending in Canada: recent trends and causes. Med Care 2004;42(7):635-42. [DOI] [PubMed]