Abstract

ACCEPTANCE OF AN EVIDENCE-BASED CONCEPTUALIZATION OF WOMEN'S SEXUAL RESPONSE combining interpersonal, contextual, personal psychological and biological factors has led to recently published recommendations for revision of definitions of women's sexual disorders found in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM–IV-TR). DSM-IV definitions have focused on absence of sexual fantasies and sexual desire prior to sexual activity and arousal, even though the frequency of this type of desire is known to vary greatly among women without sexual complaints. DSM-IV definitions also focus on genital swelling and lubrication, entities known to correlate poorly with subjective sexual arousal and pleasure. The revised definitions consider the many reasons women agree to or instigate sexual activity, and reflect the importance of subjective sexual arousal. The underlying conceptualization of a circular sex-response cycle of overlapping phases in a variable order may facilitate not only the assessment but also the management of dysfunction, the principles of which are briefly recounted.

Sexual difficulties are common among women, but whether a problem causing distress is a “dysfunction” as opposed to a normal or logical response to difficult circumstances (e.g., a problem with the relationship, sexual context or cultural factors) remains controversial. Surveys of patients in physicians' offices suggest that each year, family practitioners will see several women or couples who present with sexual problems, and even more if the physician inquires about patients' sexual health.1

Sexual difficulties are particularly prevalent among women seeking routine gynecological care.2 In population surveys, some 30%–35% of women aged 18–70 have reported a lack of sexual desire during the previous 1–12 months.3,4

Research into women's sexual function over the past 2 decades has brought into question previous views, definitions and diagnostic labels such as those still found in DSM–IV-TR.5 Previous definitions of women's sexual dysfunction were based on the linear model of human sex response of Masters and Johnson,6 as revised by Kaplan.7 The model assumes a linear progression from an initial awareness of sexual desire to one of arousal with a focus on genital swelling and lubrication, to orgasmic release and resolution. The resulting diagnostic categories such as hypoactive sexual desire disorder, female sexual arousal disorder and female orgasmic disorder reflected this linear and rather genitally focused model of sexual function. Thus, relatively discrete, non-overlapping phases of sexual response were portrayed and discrete dysfunctions defined.

The evidence to date shows that many facets of women's sexual function are at variance with this model. This review is based on the recent report of an international committee convened by the American Foundation of Urological Disease to revise and expand definitions of women's sexual dysfunction.8 The committee relied on empirical and clinical research as well as clinical experience. Literature searches provided the background to extensive collaboration from September 2002 to February 2003. Informal pilot testing of the committee's conclusions in clinical practice, plus presentation to a large international audience, led to further revisions over the next 6 months, acceptance by the Second International Consensus of Sexual Medicine9 and subsequent publication.9,10

After a review of normal characteristics of women's sexual motivation and interest, sexual arousability and response, this article presents recommended expanded and revised definitions of women's sexual dysfunction, along with suggested approaches to diagnosis and treatment.

Normal sexual function in women

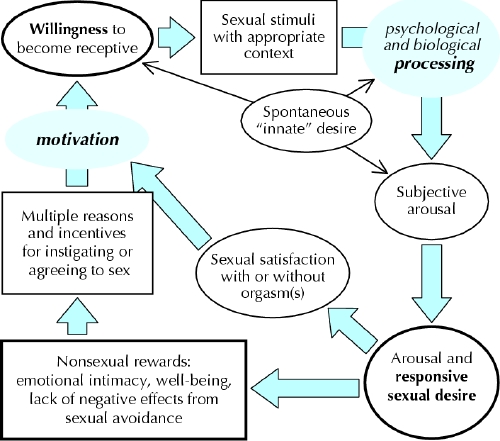

Clinical and empirical studies, mainly of North American and European adult women without sexual complaints, have clarified sexual response cycles that are different from the linear progression of discrete phases already mentioned. Women describe overlapping phases of sexual response in a variable sequence that blends the responses of mind and body (Fig. 1).11,12,13,14 That women have many reasons for initiating or agreeing to sex with their partners is an important finding.15 Women's sexual motivation is far more complex than simply the presence or absence of sexual desire (defined as thinking or fantasizing about sex and yearning for sex between actual sexual encounters).

Fig. 1: Sex response cycle, showing responsive desire experienced during the sexual experience as well as variable initial (spontaneous) desire. At the “initial” stage (left) there is sexual neutrality, but with positive motivation. A woman's reasons for instigating or agreeing to sex include a desire to express love, to receive and share physical pleasure, to feel emotionally closer, to please the partner and to increase her own well-being. This leads to a willingness to find and consciously focus on sexual stimuli. These stimuli are processed in the mind, influenced by biological and psychological factors. The resulting state is one of subjective sexual arousal. Continued stimulation allows sexual excitement and pleasure to become more intense, triggering desire for sex itself: sexual desire, absent initially, is now present. Sexual satisfaction, with or without orgasm, results when the stimulation continues sufficiently long and the woman can stay focused, enjoys the sensation of sexual arousal and is free from any negative outcome such as pain. (Modified from Basson 2001,14 and published with the permission of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.)

Recent baseline data from a longitudinal study15 of 3300 multi-ethnic, premenopausal North American women aged 42–52 who had not recently received medication affecting reproductive hormones and who had engaged in sexual activity with a partner during the past 6 months clarified their reasons both to engage sexually (to express love, for pleasure, because the partner wanted to, to relieve tension) and to refrain (lack of interest, tiredness or physical problems [their own or their partner's], or no current partner).15 These findings and those from other studies are in keeping with the sexual response cycle illustrated in Fig. 1.

At the beginning of a given sexual experience, a woman may well sense no sexual desire per se. Her motivations to be sexual are complex and include increasing emotional closeness with her partner (emotional intimacy) and often increasing her own well-being and self-image (sense of feeling attractive, feminine, appreciated, loved and/or desired, or to reduce her feelings of anxiety or guilt about sexual infrequency).15,16,17,18,19,20,21

When a woman is willing to become aroused and enjoy a sexual experience, she focuses on the sexual stimulation she and her partner supply. If the stimulation is as she wishes, sufficient time is available and she can stay focused, her sexual excitement and pleasure intensify. Clearly, the type of stimulation, the time needed and the context (both erotic and interpersonal) are all highly individual. Emotionally and physically positive outcomes will increase subsequent motivation.

Some women report desire that appears to be spontaneous (also shown in Fig. 1), leading to arousal or to more enthusiasm to find or be receptive to sexual stimuli. This type of desire has a broad spectrum across women and may be related to the menstrual cycle.22 It decreases with age,23 and at any age commonly increases with a new relationship.12,21

Previous definitions of women's sexual dysfunctions unfortunately assumed that the cycle of a woman's sexual response always began with sexual desire, sexual thoughts and fantasies, and that their absence was evidence of a disorder. In a 1992 survey of American adults,4 the most common sexual dysfunction among women 18–59 years of age was low desire, reported by just under a third of those surveyed, with little variation by age. Such results have remained consistent across studies.3,24,25 It is unclear how many of these women are simply reporting low or absent spontaneous desire but do experience triggered desire during sex. Moreover, women report that sexual fantasies can be deliberate — a means to stay focused on the sexual stimulus, rather than an indication of sexual desire.26

Another important finding is that the robust correlation seen in men between subjective arousal and genital congestion (erection) is not seen in women.27,28,29,30 Rather, sexual arousal in women is more strongly modulated by thoughts and emotions triggered by the state of sexual excitement.31 In women, photoplethysmography can be used to measure vaginal vasocongestion and hence to gauge physiological arousal. Female study participants subjected to erotic (usually visual) stimuli can meanwhile report their subjective responses (sexual arousal and positive and negative emotions) by using a Likert scale or a lever that can be moved from left (low arousal) to right (high arousal). In psychophysiological response studies,32,33 women with arousal disorders (as per DSM–IV-TR definitions), despite a lack of subjective arousal and perception of “lack of lubrication/ swelling response” while watching erotic videos, showed increases in vasocongestion comparable to those in control participants without such disorders. Only the women in the control group reported subjective arousal while watching the videos.32 Previous definitions of arousal disorder focused only on genital lubrication and/or swelling response — ignoring 25 years of research showing the poor correlation of genital engorgement with the woman's subjective arousal and excitement in response to sexual stimulation.

Causes of women's sexual dysfunctions

The model in Fig. 1 clarifies the importance of women being able to become subjectively aroused. Many psychological and biological factors may negatively influence this sexual arousability.

Interpersonal and contextual factors

In a recent national probability sample of American women 20–65 years of age,24 their emotional relationship with the partner during sexual activity and general emotional well-being were the 2 strongest predictors of absence of distress about sex. Women who defined themselves (using standard psychological instruments) to be in good mental health were much less likely than women with lower self-rated mental health to report distress about their sexual relationship (odds ratio 0.41, 95% confidence interval 0.29– 0.59). The healthier women were therefore 59% less likely to report distress about their sexual relationship. Feeling emotionally close to their partner during sexual activity decreased the odds of “slight distress” by 33% relative to “no distress,” and “marked distress” by 43%; in other words, the stronger the emotional intimacy with the partner, the less distress. Other contextual factors reported to reduce arousability included concerns about safety (risks of unwanted pregnancy and STDs, for example, or emotional or physical safety), appropriateness or privacy, or simply that the situation is insufficiently erotic, too hurried, or too late in the day.

Personal psychological factors

Frequently a woman's arousal is precluded by the nonsexual distractions of daily life, but also sometimes by sexual distractions (e.g., worry about not becoming sufficiently aroused, reaching orgasm, a male partner's delayed or premature ejaculation or a female partner's lack of orgasm). Empirical studies have shown a high correlation of desire complaints with measures of low self-image, mood instability and tendency toward worry and anxiety (without meeting the clinical definition of a mood disorder).34 Differences between a group of 46 consecutive women with a diagnosis of desire disorder without clinical depression and a control group of 100 healthy women were significant for 6 out of 8 scales in the Narcissism Inventory (a standardized self-administered instrument).34 The scales indicated that the women with desire disorder had self-esteem that was weak or even fragile, emotional instability, anxiety and neuroticism.34 Sexual arousal and orgasm, especially in a partner's presence, necessitates a certain degree of vulnerability, which is impossible for some women who cannot tolerate feelings of loss of control generally, and loss of control specifically of their body's reactions.

Further inhibiting psychological factors include memories of past negative sexual experiences, including those that have been coercive or abusive, and expectations of negative outcomes to the sexual experience (e.g., from dyspareunia or partner sexual dysfunction).13

Biological factors

The biological and pathophysiological underpinnings of normal and abnormal female sexual response are only recently receiving attention. Most of the basic science and animal experiments in this area are beyond the scope of this review. Some promising attempts are noted, however, in part because they relate attempts to ameliorate sexual dysfunction by means of off-label use of available drugs and to avoid the negative sexual side-effects of medications such as antidepressants.

Depression is strongly associated with reduced sexual function. Of 79 women with major depression surveyed before treatment with medication,35 50% reported decreased sex drive; 50%, more difficulty obtaining vaginal lubrication; and 50%, far less sexual arousal when engaging in sex. Only 50% had been sexually active during the previous month. In addition, sexual dysfunction can constitute an adverse event of antidepressant use, especially among patients who had low levels of sexual enjoyment before the onset of their depression.36 When patients are specifically asked about sexual side-effects, they are acknowledged by as many as 70%.37

Sexual dysfunction is also a common side-effect of treatment with antidepressants. Among women being treated, it has been found to be more common in those who are older, married, without postsecondary education, without full-time work, or taking concomitant medication (any type); those who have a comorbid illness that might affect sexual functioning, or a history of antidepressant- associated sexual dysfunction; those who deem sexual function unimportant; and those whose previous sexual engagements had afforded little pleasure.36

Currently under scrutiny is the role of dopamine and other neurotransmitters in influencing sex hormone receptors and how the neurotransmitters are, in turn, influenced by sex hormones. Estrogenized female animals change their sexual behaviour when administered progesterone; studies38,39 have shown that the same changes can result from dopamine or the presence of a male animal. Among 75 non-depressed women with a DSM-IV diagnosis of hypoactive sexual desire disorder who received bupropion (a dopaminergic drug; average dose 389 mg/ d) or placebo,40 improvements in pleasure, arousal and orgasm were statistically significant for those administered the active drug. Interestingly, these changes were unaccompanied by increased desire.

Testosterone itself is being investigated as to its role in sexual function and dysfunction. About half of daily testosterone production in women is from the ovary. Some women with sudden loss of all ovarian production of androgens lose their sexual arousability. Supplementation to high physiological (as opposed to pharmacologically evident) levels of testosterone recently has led to increased arousability and more intense orgasmic experiences, but not to increased sexual thinking, fantasizing or spontaneous desire.41 Of 75 surgically menopausal women aged 31–56 participating in a randomized clinical trial of testosterone versus placebo, those given testosterone (300 μg transdermally) in addition to estrogen reported increased frequency of sexual activity, sexual pleasure and intensity of orgasm.41,42 So, reminiscent of the animal model, supplementation with a dopaminergic drug or testosterone can increase some women's sexual arousability; but so too, as in the animal model, can environmental change (a new partner).12

Definitions and prevalences

Based on the recent work of the International Committee of the American Foundation of Urological Disease,8 5 major categories of dysfunction can be defined (Table 1).

Table 1

Prevalences of the recently defined categories are largely unknown, mainly because subjective arousal received little attention. It was included under the broader term of “hypoactive sexual desire disorder,” an older term used to describe women reporting an absence of spontaneous or initial desire, the lack of which does not constitute, by itself, female sexual dysfunction in the new definitions. Thus, estimated prevalences of hypoactive sexual disorder among women of 30%–40% may be wrong and misleading. When (or if) it becomes widely known that lack of spontaneous or initial desire does not by itself constitute disorder, the numbers of women diagnosed with a sexual disorder are expected to decline.

Previous figures for “female arousal disorder” were low, but as explained, they represented the numbers of women noting “lack of lubrication or swelling response” without reference to subjective arousal. The prevalence of genital arousal disorder (complaints of “genital deadness” tending to occur in midlife) is also unknown, given the previous failure to ask whether nongenital stimuli remain effective despite the loss of genital responsivity. Even the figures for women's orgasmic disorder are uncertain, as it is often stated to be comorbid with arousal disorder: DSM–IV-TR stated that an anorgasmic woman's capacity for sexual arousal had to be high or normal to fit the definition of orgasmic disorder.

Figures for the prevalence of dyspareunia and vaginismus vary markedly from study to study. A population- based assessment of 5000 women aged 18–65 recently identified about 16% reporting histories of unexplained chronic, burning, knife-like vulvar pain lasting longer than 3 months, including 8% experiencing the problem at the time of the survey.43 Although there are other causes of vulval burning (vulvodynia), vulvar vestibulitis is thought to account for the great majority. This poorly understood condition involves neurogenic inflammation in specific sites around the hymenal margin, producing areas of intense allodynia (pain from touch stimulus) typically around the lower edge of the introitus, but may involve the whole introital rim. Vulvodynia may occur spontaneously, or symptoms may be limited to introital dyspareunia and postcoital vulvodynia. The overall cumulative incidence of those who reported inability to have sexual intercourse because of the pain was 10%.

Publications about persistent sexual arousal and Internet surveys of its prevalence are only very recent. Most clinicians have seen very few (mostly older) women with this highly distressing syndrome.

Diagnosis and management

Given that a woman's sexual function is a consequence of her current psychosocial and interpersonal context, which is determined to some degree by her sexual and medical history and medications, the international committee8 recommends that physicians recognize 3 factors that contribute to sexual dysfunction: past psychosexual development; current life context; and medical factors, including comorbid illness, drugs and previous surgery. Sexual dysfunction can be a symptom of an underlying disorder, or have causes outside the patient herself. It is important to avoid “pathologizing” women by diagnosing a sexual disorder based on a normal response, such as tiredness or the side effect of a drug. Simultaneously, it is essential not to imply that dysfunction is absent or discredited simply because the cause is external to the patient. A simple analogy is the woman with neck strain and tension headaches from persistent work at a computer with poor desk height. Clearly, the solution is to adjust her working environment; nevertheless, she is given a medical diagnosis, even though there is almost certainly nothing intrinsically wrong with her cervical spine.

This has consequences for case management. The woman who has poor emotional intimacy with her partner, has possibly many distractions from her children, is tired from her job and is attempting to be sexual perhaps without the required context and needed specific sexual stimulation is reacting normally by not becoming aroused, being desirous or experiencing any orgasm. There may well be nothing wrong with her sex response system per se. Nevertheless, if she reports and suffers from dysfunction, her problems should be addressed, the underlying conditions identified and changes recommended.

Based on a careful history in which the physician helps the patient construct her sex response cycle (Fig. 1), problem areas will be identified.11 Thus the physician provides insight and direction to the many changes that need to be made by the woman and her partner. Having clarified the problems, the physician may be able to assist with some. For example, a partner's premature ejaculation can be addressed, the sexual context improved, depression treated, local estrogen prescribed, the couple referred for relationship therapy, and either or both partners can be referred for psychotherapy to address learned patterns of thinking and behaviour stemming from childhood traumas and experiences.

Approach to history and diagnosis

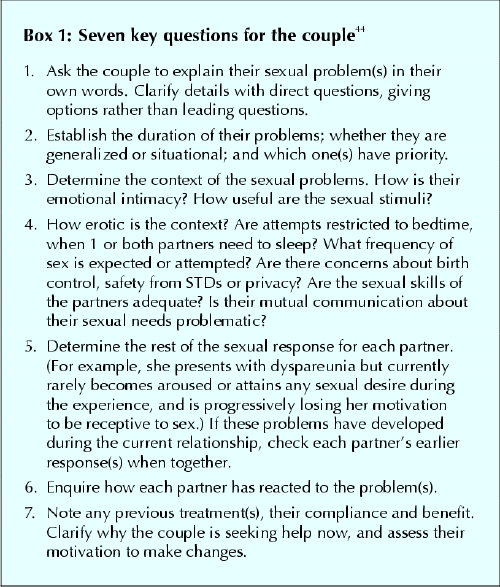

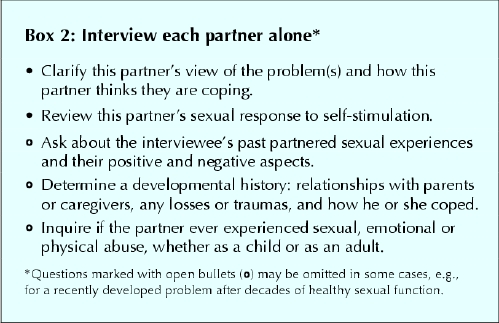

During the general systems enquiry, sexual function can be assessed after the enquiries about menstruation, dysmenorrhea or postmenopausal symptoms. When the answer to the question “Do you have any sexual concerns?” is positive, a separate visit may be necessary to fully assess and outline management. It is usually necessary to interview the couple, as well as each partner separately: Box 144 and Box 2 outline key questions to ask in either case.

Box 1.

Box 2.

Distress from any given dysfunction is highly variable. Indications of distress (at minimum, notations indicating severe, moderate or mild distress) are needed, in addition to qualitative descriptors such as lifelong/acquired and situational/generalized.8

Conclusion

Newly published revised, expanded definitions of women's sexual dysfunctions attempt to acknowledge the highly contextual nature of women's sexuality. To aid clinical management of these dysfunctions, these definitions now emphasize assessment of the context of women's problematic sexual experiences. Definitions of dysfunction continue to reflect phases of sexual response, but they now clarify the tendency of the phases to overlap (especially desire, arousal and expectation, which usually contribute to dysfunctions). The new focus is away from spontaneous or initial desire and toward triggered desire accompanying arousal. Appropriate attention is now paid to the poor correlation between subjective sexual arousal or excitement and objective measures of increases in genital vasocongestion.

These new expanded and revised definitions form part of the Second International Consultation on Sexual Medicine: Men and Women's Sexual Dysfunctions,42,45 available later this year on the Web. The ultimate validity and reliability of these revisions must, of course, be tested formally in both clinical and research settings.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks to Dr. Peter Rees for his helpful review of the manuscript and to Mrs. Maureen Piper for her excellent secretarial skills.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: Rosemary Basson received an honorarium from the Minnesota University Human Sexuality Group for a presentation on Oct. 9, 2004, on “Revised definitions of women's sensual dysfunction.”

Correspondence to: Dr. Rosemary Basson, B.C. Centre for Sexual Medicine, Vancouver General Hospital, 855 W 12th Ave., Vancouver BC V5Z 1M9; fax 604 875-8249; sexmed@interchange.ubc.ca

References

- 1.Nazareth I, Boynton P, King M. Problems with sexual function and people attending London general practitioners: cross-sectional study. BMJ 2003;327(7412): 423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Nusbaum MR, Gamble G, Skinner B, Heiman J. The high prevalence of sexual concerns among women seeking routine gynecological care. J Fam Pract 2000;49(3):229-32. [PubMed]

- 3.Fugl-Meyer AR, Sjögren Fugl-Meyer K. Sexual disabilities, problems and satisfaction in 18 to 74-year-old Swedes. Scand J Sexology 1999;2(2):79-105.

- 4.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors [erratum JAMA 1999;281(13):1174. Comment JAMA 1999;282(13):1229]. JAMA 1999;281(6):537-44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual for mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision [DSM–IV-TR]. Washington: the Association; 2000.

- 6.Masters WH, Johnson V. Human sexual response. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.; 1966.

- 7.Kaplan HS. Hypoactive sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther 1969;3:3-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L, Derogatis L, Fourcroy J, Fugl-Meyer K, et al. Definitions of women's sexual dysfunctions reconsidered: advocating expansion and revision [review]. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2003;24:221-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Basson R, Althof S, David S, Fugl-Meyer K, Goldstein I. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med 2004;1:24-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Basson R. Recent advances in women's sexual function and dysfunction [review]. Menopause 2004;11(6 Part 2):714-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Basson RJ. Using a different model for female sexual response to address women's problematic low sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther 2001;27:395-403. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Dennerstein L, Lehert P. Modeling mid-aged women's sexual functioning: a prospective, population-based study. J Sex Marital Ther 2004;30:173-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Graham CA, Sanders SA, Milhausen RR, McBride KR. Turning on and turning off: a focus group study of the factors that affect women's sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav 2004;33(6):527-38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Basson R. Female sexual response: the role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction [erratum Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:522]. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98: 350-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Cain VS. Johannes CB, Avis NE, Mohr B, Schocken M, Skurnick J, et al. Sexual functioning and practices in a multi-ethnic study of midlife women: baseline results from SWAN [Study of Women's Health Across the Nation]. J Sex Res 2003;40(3):266-76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Lunde I, Larson GK, Fog E, Garde K. Sexual desire, orgasm, and sexual fantasies: a study of 625 Danish women born in 1910, 1936 and 1958. J Sex Educ Ther 1991;17:111-5.

- 17.Hill CA, Preston LK. Individual differences in the experience of sexual motivation: theory and measurement of dispositional sexual motives. J Sex Res 1996;33:27-45.

- 18.Galyer KT, Conaglen HM, Hare A, Conaglen JV. The effect of gynecological surgery on sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther 1999;25:81-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Schultz WCM, van de Wiel HBM, Hahn DEE. Psychosexual functioning after treatment for gynecological cancer an integrated model, review of determinant factors and clinical guidelines. Int J Gynecol Cancer 1992;2:281-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Regan P, Berscheid E. Beliefs about the state, goals and objects of sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther 1996;22:110-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Klusmann D. Sexual motivation and the duration of partnership. Arch Sex Behav 2002;31(3):275-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Nappi RE, Abbiati I, Luisi S, Ferdeghini F, Polatti F, Genazzani AR. Serum allopregnanolone levels relate to FSFI score during the menstrual cycle. J Sex Marital Ther 2003;29(Suppl 1):95-102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Dudley E, Guthrie J. Factors contributing to positive mood during the menopausal transition. J Nerv Ment Dis 2001;189: 84-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Bancroft J, Loftus J, Long JS. Distress about sex: a national survey of women in heterosexual relationships. Arch Sex Behav 2003;32:193-208. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Shokrollahi P, Mirmohamadi M, Mehrabi F, Babaei G. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women seeking services at family planning centers in Tehran. J Sex Marital Ther 1999;25:211-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Garde K, Lunde I. Female sexual behaviour: a study in a random sample of 40-year-old women. Maturitas 1980;2:225-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Van Lunsen RH, Laan E. Genital vascular responsiveness and sexual feelings in midlife women: psychophysiologic, brain, and genital imaging studies [review]. Menopause 2004;11(6 Pt 2):741-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Brotto LA, Gorzalka BB. Genital and subjective sexual arousal in postmenopausal women: influence of laboratory-induced hyperventilation. J Sex Mar Ther 2002;28(Suppl 1):39-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Meston CM, Heiman JR. Ephedrine-activated physiological sexual arousal in women. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998;55:652-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Maas CP, ter Kuile MM, Laan E, Tuijnman CC, Weijenborg PT, Trimbos JB, et al. Objective assessment of sexual arousal in women with a history of hysterectomy. BJOG 2004;111:456-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Laan E, Everaerd W, van Bellen G, Hanewald G. Women's sexual and emotional responses to male- and female-produced erotica. Arch Sex Behav 1994; 23(2):153-69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Morokoff PJ, Heiman JR. Effects of erotic stimuli on sexually functional and dysfunctional women: multiple measures before and after sex therapy. Behav Res Ther 1980;18:127-37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Brotto LA, Basson R, Gorzalka BB. Psychophysiological assessment in premenopausal sexual arousal disorder. J Sex Med 2004;1:266-77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Hartmann U, Heiser K, Rüffer-Hesse C, Kloth G. Female sexual desire disorders: subtypes, classification, personality factors and new directions for treatment [review]. World J Urol 2002;20:79-88. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Kennedy SH, Dickens SE, Eisfeld BS, Bagby RM. Sexual dysfunction before antidepressant therapy in major depression. J Affect Disord 1999;56:201-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Clayton AH, Pradko JF, Croft HA, Montano CB, Leadbetter RA, Bolden-Watson C, et al. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction among new antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:357-66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, Rico-Villademoros F. Incidence of sexual dysfunctions associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multi-center study of 1022 outpatients. Spanish Working Group for the Study of Psychotropic-Related Sexual Dysfunction [comment J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:168]. J Clin Psychiatry 2001;62(Suppl 3):10-21. [PubMed]

- 38.Mani SK, Allen JMC, Clark JH, Blaustein JD, O'Malley BW. Convergent pathways for steroid hormone– and neurotransmitter-induced rat sexual behavior. Science 1994;265(5176):1246-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Blaustein JD. Progestin receptors: neuronal integrators of hormonal and environmental stimulation [review]. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;1007:238-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Segraves RT, Clayton A, Croft H, Wolf A, Warnock JE. Bupropion sustained release for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24(3):339-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, Casson PR, Buster JE, Redmond GP, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med 2000:343(10):682-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Basson R, Weijmar Schultz WCM, Binik YM, Brotto LA, Eschenbach DA, Laan E, et al. Women's desire and arousal disorders and sexual pain. In: Lue T, Basson R, Rosen R, Giuliano F, Khoury S, Montossi F, editors. Sexual medicine: sexual dysfunctions in men and women. Paris: Health Productions; 2004. p. 851-974.

- 43.Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: Have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc 2003;58(2):82-8. [PubMed]

- 44.Basson R. Introduction to special issue on women's sexuality and outline of assessment of sexual problems [review]. Menopause 2004;11(6 Pt 2):709-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L, Derogatis L, Fourcroy J, Fugl-Meyer K, et al. Revised definitions of women's sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2004;1:40-8. [DOI] [PubMed]