Abstract

Coral reefs are ecologically significant habitats. Coral-algal symbiosis confers ecological success on coral reefs and coral-microbial symbiosis is also vital to coral reefs. However, current understanding of coral-microbial symbiosis on a genomic scale is largely unknown. Here we report a potential microbial symbiont in corals revealed by metagenomics-based genomic study. Microbial cells in coral were enriched for metagenomic analysis and a high-quality draft genome of “Candidatus Prosthecochloris korallensis” was recovered by metagenome assembly and genome binning. Phylogenetic analysis shows “Ca. P. korallensis” belongs to the Prosthecochloris clade and is clustered with two Prosthecochloris clones derived from Caribbean corals. Genomic analysis reveals “Ca. P. korallensis” has potentially important ecological functions including anoxygenic photosynthesis, carbon fixation via the reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle, nitrogen fixation, and sulfur oxidization. Core metabolic pathway analysis suggests “Ca. P. korallensis” is a green sulfur bacterium capable of photoautotrophy or mixotrophy. Potential host-microbial interaction reveals a symbiotic relationship: “Ca. P. korallensis” might provide organic and nitrogenous nutrients to its host and detoxify sulfide for the host; the host might provide “Ca. P. korallensis” with an anaerobic environment for survival, carbon dioxide and acetate for growth, and hydrogen sulfide as an electron donor for photosynthesis.

Introduction

Coral reefs are significant marine ecosystems, but they are declining at an alarming rate, primarily due to climate change, ocean acidification, and anthropogenic disturbances1, 2. Reef-building corals form symbiotic associations with dinoflagellates of the genus Symbiodinium 3. These symbiotic algae provide organic nutrients for coral growth and calcification allowing reef formation in nutrient-limited oceans, while they gain inorganic carbon, essential elements and refuge from the host corals in return3. In addition to symbiotic algae, highly diverse and abundant prokaryotic microbes have been found in the coral mucus, tissue, and skeleton4. Coral hosts can benefit from these microbes through the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles and from antimicrobial defense, which may be critical in promoting coral growth and preventing disease5, 6. The term coral holobiont has been used to decribe the entity consisting of the coral host, Symbiodinium, and associated microbes including bacteria, archaea, fungi, viruses, protozoa, and other unknown components7. The coral holobiont is a highly dynamic system mediated by complex interactions between the coral host and its members, because of constant exposure to a changing environment. Exploration of potential coral microbial symbiots involved in these complex interactions is crucial to strengthen our understanding of symbiosis in the coral holobiont, contributing to a better coral reef conservation.

Green sulfur bacteria are thought to have an ancient origin on Earth, and are ecologically and biogeochemically important drivers of the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles8, 9. They are mostly found in anoxic aquatic environments with both light and sulfide, performing anoxygenic photosynthesis using electrons generated by sulfur oxidation10. Green sulfur bacteria fix carbon dioxide via the reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle but some organic compounds like acetate and pyruvate can be assimilated during mixotrophic growth9, 11. As they are able to use nitrogen gas as the sole nitrogen source for growth, they are nitrogen fixers12. Green sulfur bacteria are grouped taxonomically under the family Chlorobiaceae in the phylum Chlorobi 13, which are phylogenetically distant from the other phototrophic bacteria in the phyla Chloroflexi, Cyanobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Firmicutes. Most identified green sulfur bacteria are free-living species from the genera Prosthecochloris, Chlorobium, and Chlorobaculum. However, Chlorobium chlorochromatii can form a prokaryotic symbiosis with another bacterium “Candidatus Symbiobacter mobilis” in the phototrophic consortium “Chlorochromatium aggregatum”14. These two species can benefit from each other through metabolic exchange, sensing and moving towards light and sulfide, and electron cycling15.

Compared with the well-known coral-algal symbiosis, coral-microbial symbiosis remains largely unknown because limited evidence has been achieved to address this issue. Coral metagenomic studies have been performed previously16–19, but metagenomics-based genomic analysis of potential coral microbial symbionts is still a knowledge gap that requires to be filled. Current understanding of potential coral-microbial symbiosis mostly comes from 16S rRNA gene based analyses20, 21. The purpose of this study was therefore to explore potential microbial symbionts in corals through massively parallel sequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons, to recover potential genomes through metagenomics-based genome binning, and to elucidate potential symbiotic relationships with coral hosts on a genomic scale. In the present study, we enriched microbial cells for coral metagenomic analysis, successfully identified a green sulfur bacterium “Candidatus Prosthecochloris korallensis” as a potential microbial symbiont in corals, and analysed the metabolic pathways of the bacterium to gain insights into the mechanisms of coral-microbial symbiosis. This study will provide a new understanding of coral-microbial symbiosis on a genomic scale.

Results and Discussion

Discovery of “Ca. P. korallensis” in hard corals

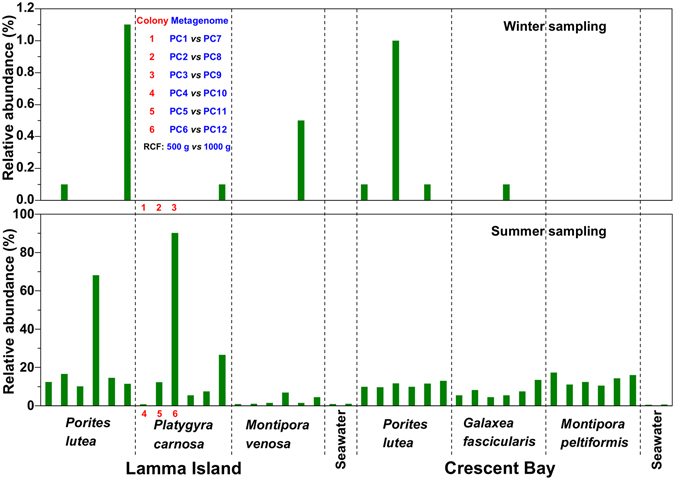

To explore ecologically important bacterial species in local corals, we studied samples of Porites lutea, Platygyra carnosa and Montipora venosa from Lamma Island and Porites lutea, Galaxea fascicularis and Montipora peltiformis from Crescent Bay collected in both winter and summer, 2014 (Fig. 1 and Table S1). As shown in Fig. 2, multiplexed 16S amplicon sequencing identified an operational taxonomic unit (OTU), i.e. “Ca. P. korallensis”, which was highly abundant (0.7–90.1%, mean 13.42%) in summer coral samples, but had a very low abundance (~0–1.1%, mean 0.09%) in winter coral samples. For comparison, its relative abundance in seawater samples was 0.5–1% (mean 0.75%) in summer and 0% in winter. This finding indicates that “Ca. P. korallensis” propagates well in summer but not well in winter and that it grows well in corals but not well in seawater. Because members of Prosthecochloris are green sulfur bacteria and “Ca. P. korallensis” can be highly abundant in local corals, “Ca. P. korallensis” may play an important role in the coral holobionts. To reveal its potential ecological functions, we have recovered its genome from the coral metagenome. As shown in Fig. 2, coral colonies 1–3 (winter samples) and 4–6 (summer samples) of P. carnosa were selected for the following metagenomic study.

Figure 1.

Coral sampling map for the present study. Corals grown in Lamma Island and Crescent Bay were collected in winter (March) and summer (October), which is located in the southwest and northeast of Hong Kong respectively. The geographic map was generated by Ocean Data View 4.7.2 (Schlitzer, R., Ocean Data View, odv.awi.de, 2017).

Figure 2.

Relative abundance of “Ca. P. korallensis” revealed by 16S amplicon sequencing and analysis. The labels showing 1–3 in winter sampling and 4–6 in summer sampling were samples collected from six colonies of P. carnosa which were used for metagenomic study to recover the genome of “Ca. P. korallensis”. Colonies 1–6 of P. carnosa were enriched twice to generate metagenomes PC1–6 (500 g RCF) and PC7–12 (1000 g RCF), respectively. “PC” is the abbreviation of the initial letters of the species name “Platygyra carnosa”.

Enrichment effect of “Ca. P. korallensis” in coral metagenome

Information for the 12 metagenome sequencing datasets before and after quality control is summarized in Table S2. The percentage of clean bases was 90–92% and 2.4–3.5 giga base pairs (Gb) of clean data were finally obtained for each sample. The microbial enrichment effect was evaluated through metagenome sequencing and 16S amplicon sequencing, both of which were conducted for the 12 enriched DNA samples (Fig. 3A). The result showed that the enrichment effect for the second batch (PC7–12) was much better than the first batch (PC1–6) because more bacteria were obtained in the second batch than the first batch. Algae were removed effectively in the second batch, but much more were retained in the first batch. It is important to note however, that coral and other components could not be removed in both batch enrichments. These findings suggested that microbes could be enriched efficiently when algae were removed successfully, and that 500 g relative centrifugal force was insufficient to pellet the algal cells but 1000 g was sufficient. The 16S amplicon sequencing data revealed that the target OTU “Ca. P. korallensis” was highly enriched in datasets PC6, PC11, and PC12 (Fig. 3B). This finding was consistent with the result of the metagenome sequencing data (Figure S1). Hence, the PC6, PC11, and PC12 datasets were selected for the following metagenome assembly. “Ca. P. korallensis” was absent with no enrichment for colonies 1–3 (Fig. 2) but it was detected with enrichment in PC1–3 and PC 7–9 (Fig. 3B), indicating “Ca. P. korallensis” actually was present in winter corals but at a very low level. The presence of “Ca. P. korallensis” in winter corals demonstrates that it is not an opportunistic colonist of corals.

Figure 3.

Enrichment effects of “Ca. P. korallensis” in coral metagenomic sequencing datasets (A) and 16S amplicon sequencing datasets (B). PC1–6 and PC7–12 represent the first (500 g RCF) and the second (1000 g RCF) batch of microbial cell enrichment, respectively. “PC” is the abbreviation of the initial letters of the species name “Platygyra carnosa”.

Genome recovery of “Ca. P. korallensis” through genome binning

Metagenome assembly using SPAdes was conducted on the PC6, PC11, and PC12 datasets individually. The best assembly for each dataset was used for the following genome binning. The draft genome of “Ca. P. korallensis” (Supplementary Dataset 1) was successfully recovered in PC12 assembly using differential sequencing coverage of PC11 and PC12 metagenome datasets (Fig. 4). There were about 37-fold and 160-fold sequencing coverages for the target genome in the PC11 and PC12 datasets, respectively. Additionally, the draft genome of “Ca. P. korallensis” could be recovered from any one assembly of PC6, PC11, and PC12 using any two datasets from them (data not shown). The draft genome of “Ca. P. korallensis” consists of 68 contigs, with a size of 2,583,763 base pairs (bp). The longest contig and N50 size is 264,073 bp and 106,492 bp, respectively. The quality of the genome was further assessed with its relatives using two calculations (Table 1). The draft genome of “Ca. P. korallensis” was nearly complete and recovered with an extremely low level of contamination, i.e. 99.45% completeness and 1.10% contamination, estimated by CheckM. The draft genome of “Ca. P. korallensis” has 2,514 genes, including 2,482 protein-coding genes, 29 tRNA genes, and 3 rRNA genes, and the GC content is 48.3%.

Figure 4.

Genome recovery of “Ca. P. korallensis” from the coral metagenome datasets PC11 and PC12 using the differential coverage genome binning method.

Table 1.

Genome comparison and quality validation between “Ca. P. korallensis” and its relatives. There are eight relatives for which genome is available including Chlorobium phaeobacteroides BS1, Prosthecochloris aestuarii DSM 271, Chlorobium limicola DSM 245, Chlorobium phaeobacteroides DSM 266, Chlorobium ferrooxidans DSM 13031, Chlorobium phaeovibrioides DSM 265, Chlorobaculum parvum NCIB 8327, and Chlorobaculum tepidum TLS. Total and unique essential single-copy genes (ESCGs) were evaluated using the genome binning program package. Completeness (%) and contamination (%) were validated by CheckM.

| Genome | Size (Mb) | GC% | Protein | rRNA | tRNA | Total ESCGs | Unique ESCGs | Completeness | Contamination |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Ca. P. korallensis” | 2.58 | 48.3 | 2,482 | 3 | 29 | 105 | 104 | 99.45 | 1.10 |

| BS1 | 2.74 | 48.9 | 2,588 | 6 | 46 | 106 | 105 | 99.45 | 0.00 |

| DSM 271 | 2.58 | 50.1 | 2,379 | 3 | 46 | 106 | 104 | 98.90 | 0.27 |

| DSM 245 | 2.76 | 51.3 | 2,560 | 6 | 48 | 106 | 105 | 99.98 | 0.00 |

| DSM 266 | 3.13 | 48.4 | 2,881 | 6 | 47 | 106 | 105 | 99.45 | 0.00 |

| DSM 13031 | 2.54 | 50.1 | 2,338 | 3 | 46 | 91 | 90 | 95.66 | 0.00 |

| DSM 265 | 1.97 | 53.0 | 1,793 | 3 | 45 | 108 | 106 | 98.36 | 1.09 |

| NCIB 8327 | 2.29 | 55.8 | 2,098 | 6 | 51 | 107 | 105 | 98.89 | 0.28 |

| TLS | 2.15 | 56.5 | 2,008 | 6 | 50 | 106 | 105 | 98.90 | 0.55 |

Phylogenetic analysis between “Ca. P. korallensis” and its relatives

The unrooted full-length 16S phylogenetic tree illustrates the evolutionary relationships between “Ca. P. korallensis” and its relatives (Fig. 5). The Prosthecochloris, Chlorobium, and Chlorobaculum clades are clearly divided, representing the most common genera in the phylum Chlorobi. These genera belong to the green sulfur bacterial family Chlorobiaceae. Interestingly, “Ca. P. korallensis” and two Prosthecochloris clones derived from the Caribbean coral Montastraea faveolata are closely clustered into a coral-associated Prosthecochloris clade, sharing ~99.5% identity in nearly full-length of the 16S rRNA gene sequence22. The other Prosthecochloris species are free-living isolates, which are phylogenetically distant from the coral-associated Prosthecochloris clade. This suggests that “Ca. P. korallensis” might live a different lifestyle. The phylogenetic analysis classified the species into the genus Prosthecochloris. We tentatively propose the name “Candidatus Prosthecochloris korallensis”, where korallensis is a latinized form of koráli, the Greek word for coral, reflecting it was found in corals.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis for “Ca. P. korallensis” and its relatives using full-length 16S rRNA gene. The neighbour-joining tree was constructed using MEGA 6.06 with 1000 bootstrap replication test. The bootstrap values higher than 50% are shown. The scale bar 0.01 indicates 1% nucleotide substitution.

Genome comparison between “Ca. P. korallensis” and its relatives

The genome properties of “Ca. P. korallensis” and eight relatives for which genome is available are summarized in Table 1. The draft genome of “Ca. P. korallensis” has a size of 2.58 mega base pairs (Mb), which is in the middle of the genome size range (1.97–3.13 Mb) for the nine species. However, “Ca. P. korallensis” has the lowest GC content and the smallest number of tRNA genes. Each genome has 1–2 copies of the ribosomal RNA operon. All the genomes compared have a complete carbon fixation pathway via the rTCA cycle (Fig. 6). Each cycle fixes two molecules of carbon dioxide and produces one molecule of acetyl-CoA, which is then assimilated into pyruvate and phosphoenolpyruvate to form central metabolites and to synthesize cellular components. Most of the enzymes involved in the rTCA cycle are shared with the TCA cycle, but three key enzymes, i.e. ATP citrate lyase, fumarate reductase, and ketoglutarate synthase (labelled in Fig. 6), allow the TCA cycle to run in the reverse direction11. Nitrogen fixation is the only inorganic nitrogen metabolism pathway found in all of the compared genomes (Fig. 6). This pathway allows these bacteria to convert environmental nitrogen gas into nitrogenous nutrients. Although the genomes compared share the same carbon and nitrogen fixation pathways, they show different sulfur metabolism capabilities (Fig. 6). For example, “Ca. P. korallensis” might oxidize sulfide to sulfate to produce more electrons for carbon reduction in the rTCA cycle, but it is unable to convert thiosulfate to sulfate through the thiosulfate-oxidizing SOX enzyme system. All genomes compared have a complete pathway for bacteriochlorophyll (BChl) biosynthesis (Figure S2), which is essential for the development of photosynthetic apparatus in green sulfur bacteria, i.e. chlorosomes. These results show that “Ca. P. korallensis” has many genomic features in common with its relatives.

Figure 6.

Carbon, sulfur, and nitrogen metabolism for “Ca. P. korallensis” and its relatives. Each color indicates a specific bacterium with a certain function. Blank shows lack of a certain function. Black boxes represent three key enzymes for rTCA cycle including ATP citrate lyase, fumarate reductase, and ketoglutarate synthase. All compared genomes have a complete carbon fixation pathway via rTCA cycle, but nitrogen fixation is the only pathway for inorganic nitrogen metabolism. All the genomes compared exhibit the abilities to oxidize sulfide to sulfur, but several of them might even oxidize sulfide to sulfate including “Ca. P. korallensis”, BS1, and TLS. “Ca. P. korallensis” has no ability to convert thiosulfate to sulfate through the thiosulfate-oxidizing SOX enzyme system.

Core metabolic pathways of “Ca. P. korallensis”

A schematic representation based on genomic analysis is proposed to provide a better understanding of how “Ca. P. korallensis” captures sunlight and converts it to chemical energy and how “Ca. P. korallensis” fixes carbon dioxide and converts it to cell components (Fig. 7). Light energy is captured by the light-harvesting pigments (e.g. BChl c, d, or e) in the photosynthetic apparatus over a broad spectrum. The light energy is then transferred to the baseplate (i.e. the complex of chlorosome protein CsmA and BChl a), to the Fenna-Matthews-Olson complex (i.e. the complex of protein and BChl a), and finally to the cytoplasmic membrane bound reaction centre (i.e. the complex of proteins, BChl a, and other co-factors)23. Hydrogen and chemical energy generated in the reaction centre are used to assimilate carbon dioxide in the rTCA cycle. The intermediate products of the rTCA cycle such as acetyl-CoA, pyruvate, phosphoenolpyruvate, and oxaloacetate might be used in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, amino acids, purines, and pyrimidines, which are essential for the further synthesis of biological macromolecules. The assimilated carbon dioxide and chemical energy might be stored in a stable form via gluconeogenesis using phosphoenolpyruvate as the substrate (Figure S3). Potential glycolysis (Figure S3) and TCA cycle (Figure S4) pathways are found in the genomes of “Ca. P. korallensis” and its relatives, indicating that “Ca. P. korallensis” may utilize carbon storage for cell activities when needed. It has been experimentally demonstrated that the TCA cycle also works in a green sulfur bacterium11. Genomic and experimental analyses reveal that green sulfur bacteria are able to assimilate a few organic compounds like acetate and pyruvate, but acetate or pyruvate cannot be used as the sole carbon source for growth without carbon dioxide11, 24. Thus, carbon dioxide is not only required for the rTCA cycle but is essential in the assimilation of acetate and pyruvate (Fig. 6). Therefore, “Ca. P. korallensis” grows photoautotrophically when it uses carbon dioxide only, but it might grow mixotrophically when additional acetate or pyruvate is available.

Figure 7.

Global metabolic pathways for “Ca. P. korallensis” and potential host-microbial interactions. Light energy is harvested and converted into chemical energy, which is used to assimilate carbon dioxide in the rTCA cycle. The intermediates generated in the rTCA cycle might be used for the biosynthesis of fatty acids, amino acids, purines, and pyrimidines, which are essential for the synthesis of biological macromolecules. The fixed carbon and nitrogen sources by “Ca. P. korallensis” might be served as host’s nutrients. Host-derived carbon dioxide and acetate and host SRB-derived hydrogen sulfide might be vital for the survival of “Ca. P. korallensis”.

Potential interactions between “Ca. P. korallensis” and coral host

A host-microbial interaction profile using the genomic information of “Ca. P. korallensis” and the current understanding of green sulfur bacteria is summarized in Fig. 7. The coral host might provide an anaerobic environment in coral tissue or/and skeleton which is essential for “Ca. P. korallensis” survival and anoxygenic photosynthesis. Carbon dioxide produced by host and hydrogen sulfide generated by host sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) might serve as the carbon source and electron donor for the photoautotrophic growth of “Ca. P. korallensis”, both of which might be contributed by the coral host. It has been demonstrated that the growth of green sulfur bacterium C. tepidum TLS enhanced significantly with the addition of acetate, and its genome is also compared in this study11. In addition, the coral host can produce abundant acetate for Symbiodinium to perform lipid synthesis for it3, which is a possible acetate source for “Ca. P. korallensis”. According to these evidences, host-derived acetate might stimulate the multiplication of “Ca. P. korallensis” through acetate assimilation pathway in the mixotrophic growth, which might happen in the summer bloom period. Hydrogen sulfide is very toxic to many marine invertebrates by inhibiting cytochrome c oxidase and a type of catalase25, 26. “Ca. P. korallensis” might help coral host detoxify sulfide through oxidation of sulfide to sulfate. “Ca. P. korallensis” might also provide fixed carbon and nitrogen, intermediates of the rTCA/TCA cycles, sugars, and other nutrients to the coral host. These potential interactions between “Ca. P. korallensis” and its host suggest it might be a coral symbiont. However, follow-up experiments would be needed to truly confirm that this bacterium is a symbiont providing some sort of benefit to the coral.

Distribution of “Ca. P. korallensis” in coral host

A recent study reported that Prosthecochloris was dominant in the microbiome of the green layer in the skeleton beneath coral tissue27, but the tissue and surrounding seawater microbiomes were not investigated. Another study examined seasonal changes in coral mucus, tissue, skeleton, and seawater microbiomes, and the results revealed that Prosthecochloris was much more abundant in tissue and skeleton than in mucus, but that it was rare in winter samples and nearly absent in the seawater28. This observation is consistent with the present study (Fig. 2), which employed the composite tissue and surface skeleton for experiments. Unfortunately, the previous and present studies did not specifically localize “Ca. P. korallensis” in coral tissue or/and skeleton. But the genomic evidence of “Ca. P. korallensis” suggests it lives in the holobionts where light can reach and an anaerobic environment can form. This is understandable because the highly efficient photosynthesis using the unique light harvesting organelles of green sulfur bacteria allows them to inhabit the only lowermost part of stratified environments where minimum light intensity is available29. It is also consistent with “Ca. P. korallensis” being nearly absent in seawater because of its oxygen sensitivity and reliance on the coral host. The significantly decreased population of “Ca. P. korallensis” in winter compared with summer may be primarily caused by a low level of light intensity and temperature in winter and insufficient hydrogen sulfide because sulfate-reducing activity in the sea is controlled by temperature and organic loading, with nearly an order of magnitude difference between summer and winter30.

Prevalence of green sulfur bacteria in hard corals

Previous 16S rRNA gene based studies revealed the presence of potential green sulfur bacteria in the phylum Chlorobi with varying abundances in the hard coral Isopora palifera from southern Taiwan27, 31, P. lutea from the South China Sea28, 32, 33, Turbinaria mesenterina from subtropical Australia34, Porites astreoides from southern Caribbean35, and Mussismilia spp. from the southern Atlantic36. In addition, they were also found in the Antarctic soft coral Alcyonium antarcticum 37, ascidians of the Great Barrier Reef38, and the deep lake water sponge Baikalospongia intermedia 39. These findings suggest that green sulfur bacteria are prevalent in aquatic animals, and might play an important role in the host. A clone library based study revealed that the dominant nitrogen-fixing bacteria were Chlorobi and Cyanobacteria in healthy and diseased P. lutea, respectively33. Chlorobi was very dominant in apparently healthy colonies of I. palifera 27 and P. lutea 28, and was also predominant in healthy colonies of five coral species in this study (Fig. 2). These observations suggest that abundant green sulfur bacteria do not cause damage to the coral host under the conditions tested.

Conclusions

In the present study, we discovered an ecologically important bacterial species “Ca. P. korallensis” through 16S massively parallel sequencing and analysis. We enriched microbial cells in corals for metagenomic analysis and recovered its genome with high-quality through metagenomics-based genome binning. Genomic analysis reveals it is a green sulfur bacterium with potentially important ecological functions such as anoxygenic photosynthesis, carbon fixation via the rTCA cycle, nitrogen fixation, and sulfur oxidization. Host-microbial interaction reveals a potential symbiotic relationship and suggests that it might be a coral symbiont. The present study provides genomic insights into a potential microbial symbiont in corals and achieves a novel understanding of coral-microbial symbiosis on a genomic scale. Moreover, the success of recovery of microbial genome from coral metagenome here exhibits technical importance for future coral metagenomic study.

Methods

Coral sampling

Hong Kong is located in the northern border of the South China Sea and provides a subtropical habitat for coral development. Lamma Island (Western Hong Kong) is an estuarine environment grown with a very low coverage of coral due to the impact of freshwater runoff and pollution from the Pearl River. While Crescent Bay (Eastern Hong Kong) is an oceanic environment for coral development and thus the coral coverage is high. The two locations with contrasting environments were selected for collection of coral and seawater samples (Fig. 1). Additionally, both winter and summer samples were taken providing seasonal comparison. According to the seawater temperature monitoring data, corals collected in March and October were employed to represent winter and summer samples, respectively. In total, five coral species were used in this study: Platygyra carnosa, Porites lutea, Montipora venosa, Montipora peltiformis, and Galaxea fascicularis. Small pieces of coral skeleton with tissue were collected from apparently healthy colonies and packaged into pre-tagged sterile zipper bags. Six colonies representing biological replicates were collected for each coral species and corresponding seawater samples were also collected to determine the relationship between microbes in the environment and those associated with coral. Information about the samplings is detailed in Table S1. After sampling, the collected corals were immediately washed with sterilized seawater to remove microbes loosely attached to the coral surface, then fixed in 70% ethanol and kept on dry ice. The collected seawater was filtered through a 0.22-μm polycarbonate membrane to concentrate seawater microbes. All fixed samples were kept at −30 °C until DNA extraction.

Species and colonies selected for coral metagenomic study through 16S amplicon sequencing and analysis

Due to the large number of coral samples (72 in total), it was necessary to conduct 16S amplicon sequencing and analysis to target certain samples for metagenomic study. The total DNA of all collected coral and seawater samples was extracted to serve as PCR templates. The 16S V3-V4 regions were amplified using barcoded primer sets 341F (5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′) & 802R (5′-TACNVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′)40 and sequenced massively using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer41, 42. The 16S amplicon sequencing datasets have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRP066229. The 16S data were cleaned and analysed using QIIME43. The 97% operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were picked and profiled to identify microbes potentially correlated to corals. An interesting microbe “Ca. P. korallensis” was discovered to be potentially associated with the investigated corals we collected for the present study. To reveal its ecological roles in corals, we tried to recover its genome through metagenomics-based genome binning. Here, we selected P. carnosa as the target species and employed three summer colonies and three winter colonies for the following metagenomic study based on the considerations: i) it is one of the dominant species in Hong Kong and its population has been affected by various threats44; ii) one of the selected colonies harboured the highest relative abundance of “Ca. P. korallensis”, as high as 90.1%; iii) the selected three summer colonies formed the best gradients for the relative abundance of “Ca. P. korallensis”, which is essential for genome binning; iv) the selected three winter colonies all showed absence of “Ca. P. korallensis”, which is critical to further confirm whether it exists in winter corals or not.

Coral microbial cell enrichment, metagenomic DNA extraction, and metagenome sequencing

Coral metagenomic study is challenging because it is difficult to enrich associated microbes in the coral holobiont. We followed the well-established method19 to develop a simple enrichment protocol. Six selected colonies of P. carnosa were used for metagenomic study including colonies 1–3 collected in winter and colonies 4–6 collected in summer (Fig. 2). Each coral sample (~2 cm × 2 cm) was firstly rinsed with 1 × PBSE (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 4.3 mM Na2HPO4·7H2O, 1.4 mM KH2PO4 and 10 mM EDTA) and fully ground in 1 × PBSE using mortar and pestle. The resultant coral slurry was transferred into a 50 ml falcon tube for 5 min vortex and 1 min natural sedimentation to remove large particles. The supernatant was homogenized at 15,000 rpm for 5 min. The homogeneous matrix was centrifuged at 500/1000 g (designed as the first/second batch enrichment) for 15 min under 4 °C to remove algal cells, coral and other large components. The supernatant containing microbial cells was further centrifuged at 15,000 g for 15 min under 4 °C to concentrate microbial cells. The microbial cell pellets were finally used for metagenomic DNA extraction using FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, France). The only difference between the two batches of enrichment was the relative centrifugal force (RCF) in the removal of Symbiodinium, i.e. 500 g19 versus 1000 g18. The first and second batch DNA extracts for colonies 1–6 of P. carnosa were designated as PC1–6 (500 g RCF) and PC7–12 (1000 g RCF), respectively. “PC” is the abbreviation of the initial letters of the species name “Platygyra carnosa”. The extracted DNA samples PC1–12 were sent to Novogene (Beijing, China) for shotgun sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq platform with a paired-end (PE) 125 bp × 2 mode. The obtained metagenomic datasets have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession number SRP066452. Additionally, the 12 metagenomic DNA extracts were further analysed by 16S amplicon sequencing, as described above.

Data filtration and evaluation of microbial cell enrichment effect

The raw metagenome sequences were trimmed to remove low-quality reads using the NGS (next-generation sequencing) QC (quality control) Toolkit45 using default settings. The generated 12 clean metagenomic datasets (Table S2) were searched against the Silva SSU (small subunit) rRNA gene database46 using BLASTN with an e-value of 1 × 10−20 to recover the best hits. The SSU rRNA gene hitting reads were extracted and re-searched against the NCBI nt database using the same e-value to output 50 hits for each search. The BLASTN outputs were imported into MEGAN547 to perform taxonomic annotation and comparison using the LCA (lowest common ancestor) algorithm. Metagenomic analysis using 16S/18S as the fingerprint was combined with 16S amplicon sequencing analysis on PC1–12, which was conducted to evaluate the microbial cell enrichment effect. The metagenomic datasets showing the best performance of microbial cell enrichment were used for metagenome assembly and genome binning.

Metagenome assembly and genome binning

The selected metagenomic datasets were individually assembled into contigs by SPAdes Genome Assembler 3.1.048 and obtained the best assembly using k-mer size optimization. The draft genome of interest was recovered by a differential coverage genome binning method49. Bowtie 2 2.2.350 was employed to map short reads of the metagenomic datasets onto the assembled contigs. The contig sequencing coverage was calculated using SAMtools 0.1.1951. The contig GC content and tetranucleotide frequency (TNF) were analysed using the publically available scripts (http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/v31/n6/full/nbt.2579.html). Prodigal 2.6052 was used to predict protein-coding sequences, which were searched against hidden Markov models covering 107 bacterial proteins to identify essential single-copy genes49. The taxa of essential single-copy genes were identified by BLASTP against the NCBI nr database and MEGAN547. Genome binning was conducted in the RStudio platform with the scripts developed by Albertsen and his colleagues. All contigs were grouped based on the sequencing coverage, and the group of contigs covering the bacterium of interest was selected for further post-binning refinement using principal component analysis of the TNF. The number of total and unique essential single-copy genes of the draft genome was analysed to evaluate the completeness and contamination. CheckM 1.0.653 was further employed to assess the quality of the recovered draft genome.

Phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic classification

The ribosomal RNA genes in the binned draft genome were identified by a tool based on hidden Markov models54. The 16S rRNA gene sequence was searched against the NCBI nt and 16S rRNA gene databases to collect reference sequences for phylogenetic analysis. The neighbour-joining tree was constructed using MEGA 6.0655 with a 1000 bootstrap replication test. Clades were grouped at genus level in the phylogenetic tree and a potential new species was inferred based on the phylogenetic distance with the known species.

Genome comparison and functional analysis

All available genomes of green sulfur bacteria were downloaded from the NCBI genome database, including Chlorobium phaeobacteroides BS1 (NC_010831), Prosthecochloris aestuarii DSM 271 (NC_011059), Chlorobium limicola DSM 245 (NC_010803), Chlorobium phaeobacteroides DSM 266 (NC_008639), Chlorobium ferrooxidans DSM 13031 (NZ_AASE00000000), Chlorobium phaeovibrioides DSM 265 (NC_009337), Chlorobaculum parvum NCIB 8327 (NC_011027), and Chlorobaculum tepidum TLS (NC_002932). These genomes were analysed and compared with the draft genome of “Ca. P. korallensis”. Prokka 1.1056 was employed to annotate all compared genomes individually. The annotated protein sequences of each genome were searched against the online KEGG Automatic Annotation Server57. The generated 9 outputs with the KEGG orthology (KO) identifiers (i.e. K numbers) were merged together for metabolic pathway reconstruction and comparison using KEGG Mapper (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/mapper.html).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by the NSFC-Guangdong Joint Fund (U1301232).

Author Contributions

H.H. and P.-Y.Q. designed this study. L.C., G.Z., R.-M.T., H.T., W.Z., J.S., W.D., Y.H.W., J.Y.X., J.-W.Q., and S.L. performed the research and data analysis. L.C. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Lin Cai and Guowei Zhou contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09032-4

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hui Huang, Email: huanghui@scsio.ac.cn.

Pei-Yuan Qian, Email: boqianpy@ust.hk.

References

- 1.Hughes TP, et al. Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science. 2003;301:929–933. doi: 10.1126/science.1085046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carpenter KE, et al. One-third of reef-building corals face elevated extinction risk from climate change and local impacts. Science. 2008;321:560–563. doi: 10.1126/science.1159196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon BR, Leggat W. Symbiodinium-invertebrate symbioses and the role of metabolomics. Mar Drugs. 2010;8:2546–2568. doi: 10.3390/md8102546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg E, Koren O, Reshef L, Efrony R, Zilber-Rosenberg I. The role of microorganisms in coral health, disease and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:355–362. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radecker N, Pogoreutz C, Voolstra CR, Wiedenmann J, Wild C. Nitrogen cycling in corals: the key to understanding holobiont functioning? Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krediet CJ, Ritchie KB, Paul VJ, Teplitski M. Coral-associated micro-organisms and their roles in promoting coral health and thwarting diseases. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2013;280 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohwer F, Seguritan V, Azam F, Knowlton N. Diversity and distribution of coral-associated bacteria. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2002;243:1–10. doi: 10.3354/meps243001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell BJ, Engel AS, Porter ML, Takai K. The versatile epsilon-proteobacteria: key players in sulphidic habitats. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:458–468. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng XY, Tang KH, Blankenship RE, Tang YJ. Metabolic flux analysis of the mixotrophic metabolisms in the green sulfur bacterium Chlorobaculum tepidum. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39544–39550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frigaard NU, Bryant DA. Seeing green bacteria in a new light: genomics-enabled studies of the photosynthetic apparatus in green sulfur bacteria and filamentous anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 2004;182:265–276. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0718-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang KH, Blankenship RE. Both forward and reverse TCA cycles operate in green sulfur bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35848–35854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.157834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wahlund TM, Madigan MT. Nitrogen fixation by the thermophilic green sulfur bacterium Chlorobium tepidum. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:474–478. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.2.474-478.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davenport C, Ussery DW, Tummler B. Comparative genomics of green sulfur bacteria. Photosynth Res. 2010;104:137–152. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogl K, Glaeser J, Pfannes KR, Wanner G, Overmann R. Chlorobium chlorochromatii sp nov., a symbiotic green sulfur bacterium isolated from the phototrophic consortium “Chlorochromatium aggregatum”. Arch Microbiol. 2006;185:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0102-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu ZF, et al. Genomic analysis reveals key aspects of prokaryotic symbiosis in the phototrophic consortium “Chlorochromatium aggregatum”. Genome Biol. 2013;14 doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-11-r127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia GD, et al. Metagenomic analysis of healthy and white plague-affected Mussismilia braziliensis corals. Microb Ecol. 2013;65:1076–1086. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Littman R, Willis BL, Bourne DG. Metagenomic analysis of the coral holobiont during a natural bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef. Env Microbiol Rep. 2011;3:651–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vega Thurber R, et al. Metagenomic analysis of stressed coral holobionts. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2148–2163. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wegley L, Edwards R, Rodriguez-Brito B, Liu H, Rohwer F. Metagenomic analysis of the microbial community associated with the coral Porites astreoides. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2707–2719. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ainsworth TD, et al. The coral core microbiome identifies rare bacterial taxa as ubiquitous endosymbionts. ISME J. 2015;9:2261–2274. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrow KM, et al. Natural volcanic CO2 seeps reveal future trajectories for host-microbial associations in corals and sponges. ISME J. 2015;9:894–908. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimes NE, et al. The Montastraea faveolata microbiome: ecological and temporal influences on a Caribbean reef-building coral in decline. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:2082–2094. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pedersen MO, Linnanto J, Frigaard NU, Nielsen NC, Miller M. A model of the protein-pigment baseplate complex in chlorosomes of photosynthetic green bacteria. Photosynth Res. 2010;104:233–243. doi: 10.1007/s11120-009-9519-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisen JA, et al. The complete genome sequence of Chlorobium tepidum TLS, a photosynthetic, anaerobic, green-sulfur bacterium. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9509–9514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132181499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oeschger R, Vetter RD. Sulfide detoxification and tolerance in Halicryptus spinulosus (Priapulida): a multiple strategy. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 1992;86:167–179. doi: 10.3354/meps086167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downs CA, Fauth JE, Downs VD, Ostrander GK. In vitro cell-toxicity screening as an alternative animal model for coral toxicology: effects of heat stress, sulfide, rotenone, cyanide, and cuprous oxide on cell viability and mitochondrial function. Ecotoxicology. 2010;19:171–184. doi: 10.1007/s10646-009-0403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang SH, et al. Prevalence of potential nitrogen-fixing, green sulfur bacteria in the skeleton of reef-building coral Isopora palifera. Limnol Oceanogr. 2016;61:1078–1086. doi: 10.1002/lno.10277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, et al. Bacterial dynamics within the mucus, tissue and skeleton of the coral Porites lutea during different seasons. Sci Rep. 2014;4 doi: 10.1038/srep07320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imhoff, J. F. Biology of Green Sulfur Bacteria. In: eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, doi: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0000458.pub2 (2014).

- 30.Al-Raei AM, Bosselmann K, Bottcher ME, Hespenheide B, Tauber F. Seasonal dynamics of microbial sulfate reduction in temperate intertidal surface sediments: controls by temperature and organic matter. Ocean Dynam. 2009;59:351–370. doi: 10.1007/s10236-009-0186-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen CP, Tseng CH, Chen CA, Tang SL. The dynamics of microbial partnerships in the coral Isopora palifera. ISME J. 2011;5:728–740. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, et al. Highly heterogeneous bacterial communities associated with the South China Sea reef corals Porites lutea, Galaxea fascicularis and Acropora millepora. Plos One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang QS, et al. Diversity analysis of diazotrophs associated with corals from Xisha and Sanya, South China Sea. Aquat Ecosyst Health Manag. 2015;18:433–442. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Godwin S, Bent E, Borneman J, Pereg L. The role of coral-associated bacterial communities in Australian subtropical white syndrome of Turbinaria mesenterina. Plos One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Lanetty M, Granados-Cifuentes C, Barberan A, Bellantuono AJ, Bastidas C. Ecological inferences from a deep screening of the complex bacterial consortia associated with the coral. Porites astreoides. Mol Ecol. 2013;22:4349–4362. doi: 10.1111/mec.12392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fernando SC, et al. Microbiota of the major south Atlantic reef building coral Mussismilia. Microb Ecol. 2015;69:267–280. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0474-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webster NS, Bourne D. Bacterial community structure associated with the Antarctic soft coral. Alcyonium antarcticum. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2007;59:81–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erwin PM, Pineda MC, Webster N, Turon X, Lopez-Legentil S. Down under the tunic: bacterial biodiversity hotspots and widespread ammonia-oxidizing archaea in coral reef ascidians. ISME J. 2014;8:575–588. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalyzhnaya OV, Itskovich VB. Phylogenetic diversity of microorganisms associated with the deep-water sponge Baikalospongia intermedia. Genetika. 2014;50:765–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai L, Ye L, Tong AH, Lok S, Zhang T. Biased diversity metrics revealed by bacterial 16S pyrotags derived from different primer sets. Plos One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kozich JJ, Westcott SL, Baxter NT, Highlander SK, Schloss PD. Development of a dual-index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5112–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01043-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fadrosh DW, et al. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome. 2014;2 doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiu JW, Lau DCC, Cheang CC, Chow WK. Community-level destruction of hard corals by the sea urchin Diadema setosum. Mar Pollut Bull. 2014;85:783–788. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel RK, Jain M. NGS QC Toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. Plos One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quast C, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huson DH, Mitra S, Ruscheweyh HJ, Weber N, Schuster SC. Integrative analysis of environmental sequences using MEGAN4. Genome Res. 2011;21:1552–1560. doi: 10.1101/gr.120618.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nurk S, et al. Assembling single-cell genomes and mini-metagenomes from chimeric MDA products. J Comput Biol. 2013;20:714–737. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2013.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Albertsen M, et al. Genome sequences of rare, uncultured bacteria obtained by differential coverage binning of multiple metagenomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:533–538. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hyatt D, et al. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC bioinformatics. 2010;11 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang Y, Gilna P, Li W. Identification of ribosomal RNA genes in metagenomic fragments. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1338–1340. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:182–185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.